Chinese Path to Sports Modernization: Fitness-for-All (Chinese) and a Development Model for Developing Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

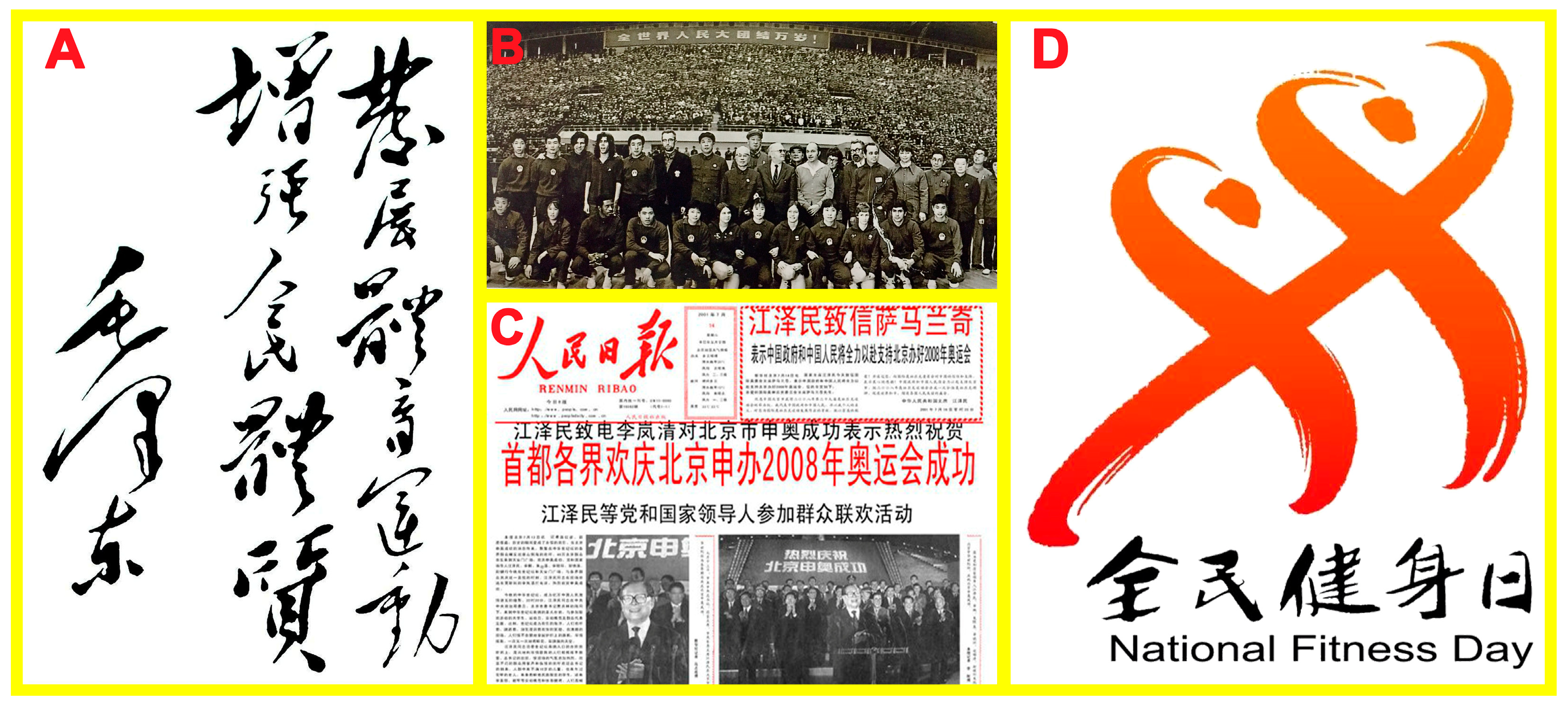

2. Chinese Path to Sports Modernization in Retrospect

2.1. Starting Stage: Introduction and Learning (1840–1949)

2.2. Exploratory Stage: Establishment and Stagnation (1949–1978)

2.3. Formative Stage: Base and Reform (1978–2012)

2.4. Development Stage: Advantages and Characteristics (2012–2022)

2.5. Uplifting Stage: All-Round and High-Quality (2022–2035)

3. The Essence of the Chinese Path to Sports Modernization

3.1. People-Centered

3.2. Top-Level Design and Universal Participation

3.3. Diverse Governance in Global Sports

4. Fitness-for-All and World: A Chinese Approach to Common Prosperity

4.1. Pioneering a Large Population with Inadequate Sports Resources

4.2. Synergizing Sectors and Resources

4.3. Advocating the Diversity of World Sports Civilizations

4.4. Revealing the Synchronous Modernization of Sports and Humanity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gilman, N. Modernization Theory Never Dies. Hist. Polit. Econ. 2018, 50, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, S.P. Political Order in Changing Societies; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. How Development Leads to Democracy: What We Know About Modernization. Foreign Aff. 2009, 88, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Argyrou, V. Tradition and Modernity in the Mediterranean: The Wedding as Symbolic Struggle; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Daily Online. Full Text: Speech by Xi Jinping at a Ceremony Marking the Centenary of the CPC. Available online: http://en.people.cn/n3/2021/0701/c90000-9867483.html (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Xi, J. Full Text: Report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. Available online: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202210/t20221025_10791908.html (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Chantelat, P. An overview of some recent perspectives on the socio-economics of sport. Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. 1999, 34, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, E. Sport in Space and Time: “Civilizing Processes”, Trajectories of State-Formation and the Development of Modern Sport. Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. 1994, 29, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownell, S. The 1904 Anthropology Days and Olympic Games: Sport, Race, and American Imperialism; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Besnier, N.; Brownell, S.; Carter, T.F. The Anthropology of Sport: Bodies, Borders, Biopolitics; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mazi Mbah, C.; Ojukwu, U. Modernization theories and the study of development today: A critical analysis. Int. J. Acad. Multidiscip. Res. 2019, 3, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos Lima, M.G. Corporate Power in the Bioeconomy Transition: The Policies and Politics of Conservative Ecological Modernization in Brazil. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, E. Modernization and Household Composition in India, 1983–2009. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2019, 45, 739–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, E.A.; Gregg, V.H. Women in Sport: Historical Perspectives. Clin. Sports Med. 2017, 36, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, H.E.; García, B. Beyond sports autonomy: A case for collaborative sport governance approaches. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2021, 13, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Bu, T.; Jiao, F. Sustainable land use and green ecology: A case from the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics venue legacy. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M. Deep and Solid Root, A Road to Long Life: The Revelation of Chinese Ancient Sports View. J. Tianjin Univ. Sport 2007, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasdalsmoen, M.; Eriksen, H.R.; Lønning, K.J.; Sivertsen, B. Physical exercise and body-mass index in young adults: A national survey of Norwegian university students. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandkvist, M.; Bjørngaard, J.H.; Ødegård, R.A.; Åsvold, B.O.; Sund, E.R.; Vie, G.Å. Quantifying the impact of genes on body mass index during the obesity epidemic: Longitudinal findings from the HUNT Study. BMJ 2019, 366, l4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. The Central Committee of the CPC and the State Council Print and Issue the Outline of the “Healthy China 2030” Plan. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Liu, K.-C. Introduction The Beginnings of China’s Modernization. Chin. Stud. Hist. 1990, 24, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, S. Eastward Transmission of Western Learning and the Evolution of Modern Sports in Shanghai, 1843–1949. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2016, 33, 1606–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Pan, D. The Introduction of Western Sports during the Opening of Macau and Its Developmental Implications. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2021, 38, 1809–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner, C. Chinese dreams of national strength and global belonging:“Iron and Blood” and the forces of evolution, 1895–1918. In Colonialism, China and the Chinese: Amidst Empires; Monteath, P., Fitzpatrick, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, F.; Hua, T. Sport in China: Conflict between Tradition and Modernity, 1840s to 1930s. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2002, 19, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S. Dewey Meets Confucius. In Narrative Inquiry into Reciprocal Learning between Canada-China Sister Schools: A Chinese Perspective; Bu, Y., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 53–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, X. Cultural Study on the Sports Spirit of the Communist Party of China in the Soviet Area. Front. Econ. Manag. 2022, 3, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G. Sports in China’s Internationalization and National Representation: China’s Participation in 1932, 1936 and 1948 Olympic Games. Chin. Hist. Rev. 2008, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Lu, Z. Representing the New China and the Sovietisation of Chinese sport (1949–1962). Int. J. Hist. Sport 2012, 29, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Saunders, J. An Historical Review of Mass Sports Policy Development in China, 1949–2009. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2019, 36, 1390–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z. Sport and Politics: The Cultural Revolution in the Chinese Sports Ministry, 1966–1976. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2016, 33, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Sports Diplomacy: The Chinese Experience and Perspective. Hague J. Dipl. 2013, 8, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.-d.; Ling, P. On period division of the sports history of new China—Also a discussion with Mr. WU Zai-tian and others. J. Phys. Educ. 2009, 16, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Henry, I. Reform and maintenance of Juguo Tizhi: Governmental management discourse of Chinese elite sport. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2017, 17, 531–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Hong, F. Historical Review of State Policy for Physical Education in the People’s Republic of China. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2012, 29, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, S.; Tan, T.-C.; Lau, P.W.C. Sport policy in China (Mainland). Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2018, 10, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Administration of Sport of China. Plan for Development of the Sports Industry During the 12th Five-Year Plan. Available online: https://www.sport.gov.cn/n315/n330/c564322/content.html (accessed on 1 April 2011).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Several Opinions of the State Council on Accelerating the Development of the Sports Industry and Promoting Sports Consumption. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-10/20/content_9152.htm (accessed on 20 October 2014).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Circular of the State Council on Printing and Issuing the National Fitness Program (2011–2015). Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2011-02/24/content_1809557.htm (accessed on 24 February 2011).

- Zhong, B. New National System: The Guarantee of Building a Sports Power. J. Shanghai Univ. Sport 2021, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Circular of the State Council on Printing and Issuing the National Fitness Program (2016–2020). Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-06/23/content_5084564.htm (accessed on 23 June 2016).

- General Office of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party; General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. The General Office of the Central Committee of the CPC and the General Office of the State Council Print and Issue the Opinions on Comprehensively Strengthening and Improving School Physical Education in the New Era. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xxgk/moe_1777/moe_1778/202010/t20201015_494794.html (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- General Administration of Sport of China; Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Notice of the Ministry of Education of the General Administration of Sports on Printing and Distributing Opinions on Deepening the Integration of Sports and Education to Promote the Healthy Development of Adolescents. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-09/21/content_5545112.htm (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Bu, T.; Li, Q.; Zou, X. Research on Green Technology Innovation and Ecological Civilization Legacy of Beijing Winter Olympic Games. Sci. Manag. Res. 2022, 40, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Outline for Building a Leading Sports Nation. Available online: http://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/201909/02/content_WS5d6d1a96c6d0c6695ff7faa3.html (accessed on 2 September 2019).

- General Administration of Sport of China. “14th Five-Year” Sports Development Plan. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-10/26/content_5644891.htm (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- General Office of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party; General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. The General Office of the Central Committee of the CPC and the General Office of the State Council Print and Issue the Opinions on Building a Higher Level of Public Service System for National Fitness. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2022-03/23/content_5680908.htm (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Langhelle, O. Why ecological modernization and sustainable development should not be conflated. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2000, 2, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Agudamu, A.; Bu, T.; Hu, K.; Matic, R.M.; Corilic, D.; Casaru, C.; Zhang, Y. Association between Evergrande FC’s club debt and Chinese Super League’s profitability from 2014 to 2019. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colglazier, W. Sustainable development agenda: 2030. Science 2015, 349, 1048–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Menhas, R. Sustainable development goals, sports and physical activity: The localization of health-related sustainable development goals through sports in China: A narrative review. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Circular of the State Council on Printing and Issuing the National Fitness Program (2021–2025). Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2021-08/03/content_5629218.htm (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 13 March 2017).

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Du, K.; Hu, D.; Zheng, G.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J. The Practical Logic of People-centered Sports Subjectivity. Chin. Sports Sci. 2021, 41, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, X. Grassroots Party Organizations Practice the Mass Line in the New Era: Predicament and Outlet. Int. J. Educ. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2022, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q. Celebrity Athletes, Soft Power and National Identity: Hong Kong Newspaper Coverage of the Olympic Champions of Beijing 2008 and London 2012. Mass Commun. Soc. 2013, 16, 888–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People’s Daily Online. 2022 National Fitness Trends Report. Available online: http://health.people.com.cn/n1/2022/0802/c14739-32491985.html (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Promoting National Fitness and Sport Consumption and Facilitating High-quality Development of Sport Industry. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-09/17/content_5430555.htm (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Zhang, T.; Ning, Z.; Dong, L.; Gao, S. The implementation of “integration of sports and medicine” in China: Its limitation and recommendations for model improvement. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1062972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Cao, C.; Gu, J.; Liu, T. A New Environmental Protection Law, Many Old Problems? Challenges to Environmental Governance in China. J. Environ. Law 2016, 28, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; Chen, S. Could campaign-style enforcement improve environmental performance? Evidence from China’s central environmental protection inspection. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 245, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Administration of Sport of China. Outdoor Sports Industry Development Plan (2022–2025). Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-11/07/content_5725152.htm (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Weidong, C.; Yin, L.; Yanbing, X.; Daojun, H.; Liu, Q.; Yao, S.; He, M.; Wang, H.; Mi, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Academic Conversations on “Chinese Socialist Sports Development Path on the Centenary of the Communist Party of China”. J. Shanghai Univ. Sport 2021, 45, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Yan, Y.; Tang, X.; Liu, S. People-Centered Comprehensive Modernization. In 2050 China: Becoming a Great Modern Socialist Country; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, T.-C. The Transformation of China’s National Fitness Policy: From a Major Sports Country to a World Sports Power. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2015, 32, 1071–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.P. Xi Jinping at Sochi: Leveraging the 2014 Winter Olympics for the China Dream. Asia Pacific J. Sport Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Law of the People’s Republic of China on Physical Culture and Sports. Available online: https://www.sport.gov.cn/n10503/c24405484/content.html (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Meng, L. Practical Experience and Enlightenment of Social Power Running Sports: Taking Wenzhou Model as an Example. Sports Cult. Guide 2022, 4, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ren, Z. Global Vision and Local Action: Football, Corruption and the Governance of Football in China. Asian J. Sport Hist. Cult. 2022, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.Q.L.; Ding, G.; Chang, W.; Wan, Y. Architecture of “Stadium diplomacy”–China-aid sport buildings in Africa. Habitat Int. 2019, 90, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, B. Comparison between the Youth Olympic Games and Olympic Games in Legacy. J. Sports Res. 2017, 31, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Theodoraki, E. Mass sport policy development in the Olympic City: The case of Qingdao—host to the 2008 sailing regatta. Perspect. Public Health 2007, 127, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- General Administration of Sport of China. Sports Statistics. Available online: https://www.sport.gov.cn/n315/n329/index.html (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Tan, T.-C.; Green, M. Analysing China’s Drive for Olympic Success in 2008. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2008, 25, 314–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhou, Y. Reference and Revelation of Leisure Sports Industry Development in Foreign Developed Countries for China. Theory Reform 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CGTN. Yao Ming Lavishly Praises Grassroots Basketball Games in Chinese Village. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6xwVe0j_4y0&ab_channel=CGTN (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. National Sports Industry Total Scale and Value Added Data Announcement in 2020. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202112/t20211230_1825760.html (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Salvo, D.; Garcia, L.; Reis, R.S.; Stankov, I.; Goel, R.; Schipperijn, J.; Hallal, P.C.; Ding, D.; Pratt, M. Physical Activity Promotion and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Building Synergies to Maximize Impact. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J. A reflection on ‘factors determining the recent success of Chinese women in international sport’. Int. J. Hist. Sport 1998, 15, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Convergence Evaluation of Sports and Tourism Industries in Urban Agglomeration of Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area and Its Spatial-Temporal Evolution. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Modernizing China in the Olympic Spotlight: China’s National Identity and the 2008 Beijing Olympiad. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 54, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zürn, M. Contested Global Governance. Glob. Policy 2018, 9, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cao, Y.; Qiao, Q.; Qian, Y. Sports in the Transnational Public Sphere: Findings from the Case of Daryl Morey’s Hong Kong Tweet. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2020, 37, 1139–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.; Wang, H.; Ali, I. A Sustainable Community of Shared Future for Mankind: Origin, Evolution and Philosophical Foundation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.P. From Integration with China to Engagement with the World: International Mega-Sports Events in Post-Handover Macau. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2016, 33, 1254–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobierecki, M.M. Sports Exchange as a Tool of Shaping State’s Image: The Case of China. Pol. Polit. Sci. Stud. 2018, 59, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaziza, M. China–Qatar Strategic Partnership and the Realization of One Belt, One Road Initiative. China Rep. 2020, 56, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttmann, A. From Ritual to Record: The Nature of Modern Sports; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, S.C. The Role of Religion in Greek Sport. In A Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: West Sussex, UK, 2013; pp. 309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, X.; Lin, D. Theory of Vitality and Metabolism——A Comparative Research on Health Concept of Ancient Chinese and Greeks. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 2007, 30, 1297–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olympic Committee. President Bach Meets Chinese State Leader President Xi—After Seeing Progress Made at Beijing 2022 Venues. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/news/president-bach-meets-chinese-state-leader-president-xi-after-seeing-progress-made-at-beijing-2022-venues (accessed on 31 January 2019).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Wan, B.; Yao, Y.; Bu, T.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y. Chinese Path to Sports Modernization: Fitness-for-All (Chinese) and a Development Model for Developing Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054203

Li J, Wan B, Yao Y, Bu T, Li P, Zhang Y. Chinese Path to Sports Modernization: Fitness-for-All (Chinese) and a Development Model for Developing Countries. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054203

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jiaomu, Bin Wan, Yaping Yao, Te Bu, Ping Li, and Yang Zhang. 2023. "Chinese Path to Sports Modernization: Fitness-for-All (Chinese) and a Development Model for Developing Countries" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054203

APA StyleLi, J., Wan, B., Yao, Y., Bu, T., Li, P., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Chinese Path to Sports Modernization: Fitness-for-All (Chinese) and a Development Model for Developing Countries. Sustainability, 15(5), 4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054203