Empowerment or Disempowerment: The (Dis)empowering Processes and Outcomes of Co-Designing with Rural Craftspeople

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Construct of Empowerment

2.2. Participatory Social Design

2.3. Craft Empowerment through Co-Design

“…craftspeople who use design were significantly optimistic, while craftspeople working in the conventional manner stated that felting is dying…Since Ayfer stepped into the field with her newly developing creative perspective for felting, she was more open to new experiments…craftspeople using design stated that they mentor at workshops at the local, national, and international level. This allows them to enlarge their network while obtaining inspiration from different approaches… overcome the limitations of locality and become more confident regarding making new experiments…the craftsperson develops an ability to provide opportunities and potentials for her local community… [a long-term result] would be support of local culture and the sustainable development of the local community.“ (p. 7)

3. Research Questions and Methods

3.1. Research Questions

- What are the elements in co-design processes that can exert positive and/or negative effects on artisan empowerment? (RQ1)

- What changes, whether good or bad, have the craftspeople undergone as co-design outcomes? (RQ2)

3.2. Methods

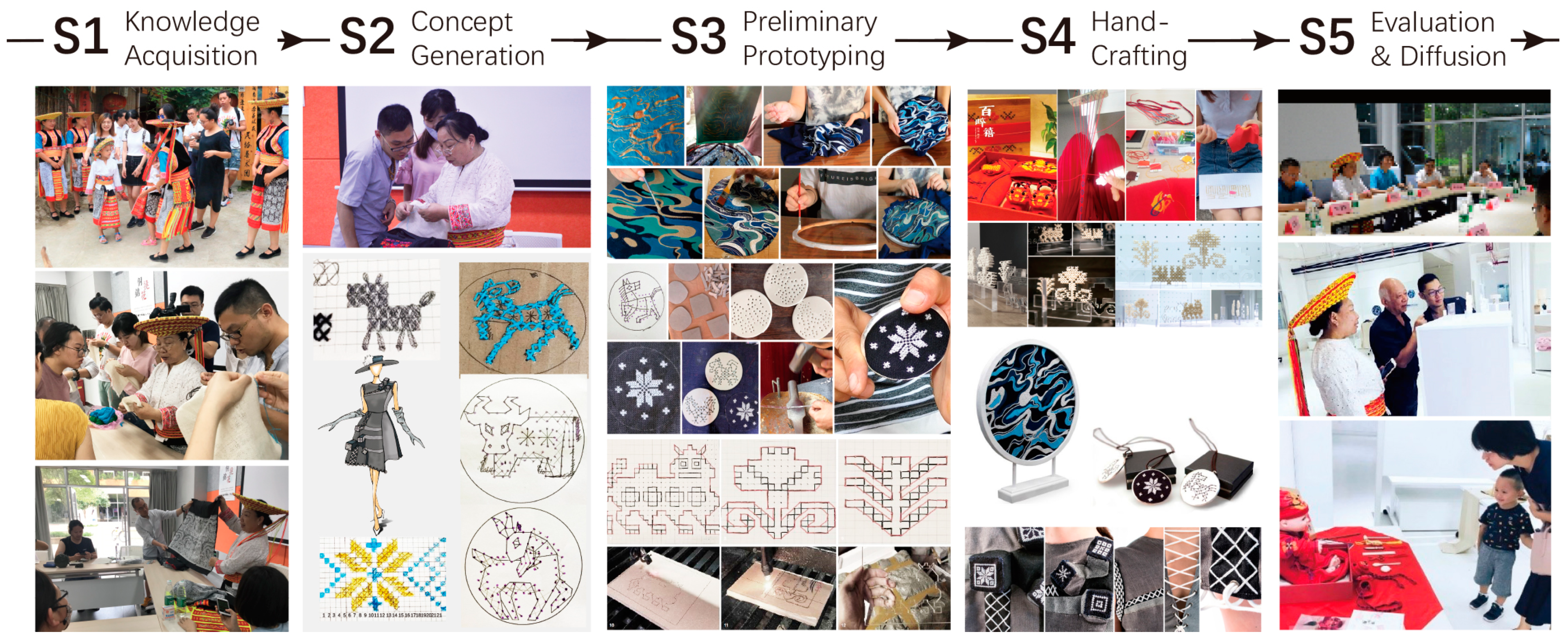

4. Empirical Cases: The Dynamics in Co-Design Processes

4.1. Case Study 1: Flowering Hua Yao

4.1.1. Knowledge Acquisition

I enjoy the atmosphere when I stitch with others in public places of the village, chattering away happily. I often reflect on my works lying in bed before sleep. I would be annoyed and could not fall into sleep if not satisfied with my works...The reason [why I put birds and plants in the stomach of a tiger] is that the tiger is pregnant and she is very hungry so she eats birds and plants… A bee motif is stitched much bigger than a frog one because the bee has spreading wings… I stitch what I see and the inspiration [of a bee motif depicted in a modern cartoon style] comes from a bee cartoon character on TV…[but] I prefer the traditional style because one expert once told me that exquisite traditional Tiao Hua is more valuable than simplified modern one.

4.1.2. Concept Generation

4.1.3. Preliminary Prototyping

4.1.4. Handcrafting

4.1.5. Evaluation and Diffusion

4.2. Case Study 2: Tiao Hua Talent Cultivation

4.2.1. Knowledge Acquisition

4.2.2. Concept Generation

4.2.3. Preliminary Prototyping

4.2.4. Handcrafting

4.2.5. Evaluation and Diffusion

4.3. Refection on the Co-Design Dynamics and Paradigms

5. Theorizing Craftspeople (Dis)empowerment through Co-Design

5.1. Theorizing the (Dis)empowerment Process of Craft-design Collaboration

5.1.1. Organization

5.1.2. Instrumentation

5.1.3. Participation

I have been invited to teach Tiao Hua in primary and vocational schools. The courses are mostly aimed to enable students to master the basic skills of conventional Tiao Hua. The teaching contents are not difficult and I generally follow the schools’ teaching arrangements and Tiao Hua textbooks. The curriculum of this project emphasizes Tiao Hua innovation which is hard yet interesting. It is the first time I take part in “designing” such a curriculum [with an innovation-orientation] and have a say on the teaching contents (personal interview in exhibition seminar, C7, August 2018).

5.1.4. Interaction

5.2. Theorizing the (Dis)empowerment Outcome of Craft-design Collaboration

5.2.1. Emotional (Dis)empowerment

I haven’t been to a university before and never thought I could stand on the podium of a famous university to teach [Tiao Hua]. It is my great honor to receive an official letter of appointment from a university. I didn’t expect I could have a say as an ordinary person in this project [Case 2]. It is an affirmation of my personal value and Tiao Hua value…The exhibition and seminar provide me much inspiration for developing Tiao Hua… I realize we could do more for Tiao Hua. [I have] full confidence in its future development (interview, C7, August 2018).

5.2.2. Cognitive (Dis)empowerment

5.2.3. Behavioral (Dis)empowerment

5.2.4. Relational (Dis)empowerment

5.3. Dialectic Discussion of Craftspeople (Dis)empowerment

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B. Analysis of the Data

Appendix C. Coded Statements of the (Dis)empowering Process and Outcome

| Co-Design Stages | (Dis)empowering Process (Actions, Activities and Contexts) | (Dis)empowering Outcome (Co-Design Effects on Craftspeople) |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Acquisition (S1) | The team sizes were small with 5–10 people (Case 1, 2) [P1-1]Organization: Team Size | Small team sizes tended to stimulate quality participation and less-confident participants were encouraged to give inputs [O1-1] (+) Emotional: Motivation, Perceived Competence |

| Multidisciplinary teams were established (Case 1, 2) [P1-2] Organization: Team Composition | Artisans gained access to diversified domains of people [O1-2] (+) Relational: Co-Creation Network Building | |

| The project was conducted in summer time when locals are more available (Case 1, 2) [P1-3] Organization: Timing | More locals participated in the co-design projects as active citizens or craft practitioners [O1-3] (+) Behavioral: Community Participation, Domain-Specific Participation | |

| The project lasted for a long duration of two months (Case 2) [P1-4] Organization: Duration | Local artisans found it hard to fully participate in the co-design process [O1-4] (−) Behavioral: Domain-Specific Participation | |

| The project was carried out in local context (Case 1) [P1-5] Organization: Choice of Venue | More locals took action to participate in different ways [O1-5] (+) Behavioral: Community Participation, Domain-Specific Participation | |

| The venue was a university space with easy access to making facilities (Case 2) [P1-6] Organization: Choice of Venue | Locals were mostly denied the chance to participate due to the ex-situ conduction of the project [O1-6] (−) Behavioral: Community Participation, Domain-Specific Participation | |

| The artisan was invited to teach and co-devise the curriculum (Case 2) [P1-7] Organization: Division of Labor, Power Relations; Participation: Level 2: Partnership | The artisan felt confident and a sense of having a say [O1-7a] (+) Emotional: Perceived Competence & Control The artisan participant gained power over non-participants [O1-7b] (−) Relational: Bridging Social Divisions | |

| The village head who was not ethnic Hua Yao was chosen as the accommodation provider and key informant (Case 1) [P1-8] Organization: Choice of Venue, Power Relations | Some Hua Yao people had a sense of distance from the design team, hampering their possible participation [O1-8] (−) Emotional: Motivation | |

| A community seminar was held to discuss development issues (Case 1) [P1-9] Participation: Level 1, 2; Instrumentation: Probing & Priming Methods; Interaction: Community Level | Locals critically examined local assets and framed development proposals [O1-9a] (+) Cognitive: Critical Systems Thinking voiced themselves as active citizens [O1-9b] (+) Behavioral: Community Participation and developed community cohesion for building a community of practice (CoP) [O1-9c] (+) Relational: Bridging Social Divisions | |

| Pre-design training courses were conducted (Case 2) [P1-10] Instrumentation: Capacity Building Methods | The artisan enhanced co-design literacy by attending the courses as one of the trainers [O1-10] (+) Cognitive: Creative Capacity Development | |

| Experts talked to artisans that they prefer complex traditional Tiao Hua to simplified contemporary ones (Case 1) [P1-11] Interaction: Intra-Organizational Level | Artisans began to realize the value of conventional Tiao Hua [O1-11a] (+) Cognitive: Critical Thinking Artisans’ enthusiasm for innovation was dampened [O1-11b] (-) Emotional: Motivation They tended to stick to traditional Tiao Hua influenced by the experts [O1-11c] (−) Behavioral: Conformist Behaviors | |

| Concept Generation (S2) | Mediating objects (e.g., vintage Tiao Hua samples and inspirational cards) and generative tools (e.g., collage and story boards) were used (Case 2) [P2-1] Instrumentation: Craft-Design Communication Tools, Generative Tools; Interaction: Intra-Organizational Level | The artisan learnt the tools for facilitating co-design communication [O2-1a] (+) Cognitive: Creative Capacity Development and applied part of them to primary school classes afterwards [O2-1b] (+) Cognitive: Skill Transfer across Domains to foster children’s creative ability [O2-1c] (+) Relational: Facilitating Others’ Empowerment |

| Tiao Hua craftspeople were excluded from this phase (Case 1) [P2-2] Participation: Level 0: Artisan Nonparticipation | The exclusiveness of S2 discouraged artisans from contributing to the project [O2-2a] (−) Emotional: Perceived Control, Motivation hindered artisans to cultivate their ability to ideate[O2-2b] (−) Cognitive: Creative Capacity Development and to form collective awareness of the craft-design alliance [O2-2c] (−) Relational: Collaborative Competence | |

| One Tiao Hua craftsperson was included this phase (Case 2) [P2-3] Participation: Level 1: Consultation | The artisan’s confidence was enhanced through providing insights into technical viability and cultural connotations [O2-3a] (+) Emotional: Perceived Competence Her ability to conceptualize in designerly ways was fostered [O2-3b] (+) Cognitive: Creative Capacity Development and her ability to co-ideate with designers was enhanced [O2-3c] (+) Relational: Collaborative Competence | |

| Preliminary Prototyping (S3) | Local artisans skilled in other crafts (e.g., bamboo) and an external manufacturer participated in S3 (Case 1) [P3-1] Participation: Level 0: (Tiao Hua) Artisan Nonparticipation; Interaction: Inter-Organizational Level | Craft combination helped build local co-creation networks [O3-1a] (+) Relational: Co-Creation Network Building One artisan expressed her intention to organize other artisans for Tiao Hua product development [O3-1b] (+) Relational: Facilitating Others’ Empowerment The involvement of external manufactures denied locals’ chance to participate [O3-1c] (−) Behavioral: Domain-Specific Participation and to learn creative knowledge concerning prototyping [O3-1d] (−) Cognitive: Knowledge Development |

| Tiao Hua artisans were excluded from S3, yet external manufactures and artisans skilled in other crafts (e.g., carpentry and ceramics) in other regions participated in S3 (Case 2) [P3-2] Participation: Level 0: (Tiao Hua) Artisan Nonparticipation; Interaction: Inter-Organizational Level | The involvement of diverse external artisans opened up opportunity for creating a trans-regional craft production network [O3-2a] (+) Relational: Co-Creation Network Building The absence of locals from S3 denied their chance to acquire creative knowledge and skills [O3-2b] (−) Cognitive: Knowledge & Skill Development and to get involved in the potential craft production system [O3-2c] (−) Behavioral: Domain-Specific Participation | |

| Although the Tiao Hua artisan was generally not engaged in S3, she as mentor generally knew the conditions of preliminary prototyping (Case 2) [P3-3] Participation: Level 0, 1: (Tiao Hua) Artisan Nonparticipation, Consultation | The craftsperson learnt the benefits and functions of modern prototyping facilities [O3-3a] (+) Cognitive: Knowledge & Skill Development and recommended the primary school where she teaches Tiao Hua buying similar facilities [O3-3b] (+) Cognitive: Knowledge & Skill Transfer across Domains; Behavioral: Creative Behavior | |

| Hand- crafting (S4) | Using prototypes as the mediating objects for craft-design communication (Case 1, 2) [P4-1] Instrumentation: Cross-Domain Communication Tools; Interaction: Intra-Organizational Level | Craftspeople felt comfortable and confident in expressing themselves through prototypes instead of sketches [O4-1] (+) Emotional: Perceived Competence |

| Tiao Hua craftspeople took a major role in this phase with occasional communication with designers (Case 1) [P4-2] Participation: Level 3: Artisan Control | Artisans felt confident and a sense of control [O4-2a] (+) Emotional: Perceived Competence & Control through contributing Tiao Hua expertise [O4-2b] (+) Behavioral: Domain-Specific Participation They critically challenged designers’ designs and expressed their ideas to reach consensus [O4-2c] (+) Relational: Collaborative Competence Designers’ low participation levels prevented artisans from raising design literacy [O4-2d] (−) Cognitive: Knowledge & Skill Development | |

| Designers as trainees mostly designed and made Tiao Hua by themselves with sporadic resort to the Tiao Hua artisan as trainer (Case 2) [P4-3] Participation: Level 0, 1: Artisan Nonparticipation, Consultation | The artisan felt a sense of fulfilment in instructing the designer trainees [O4-3a] (+) Emotional: Perceived Competence & Control and learnt new Tiao Hua materials and motif designs from designers [O4-3b] (+) Cognitive: Skill & Knowledge Development The artisan’s low participation degrees in S4[O4-3c] (−) Behavioral: Domain-Specific Participation prevented her from honing her ability to co-work with designers in terms of craft innovation [O4-3d] (−)Relational: Collaborative Competence | |

| Evaluation& Diffusion (S5) | Co-design works were evaluated and diffused in the community seminar (Case 1) [P5-1] Instrumentation: Channels of Evaluation & Diffusion; Participation: Level 1: Artisan Consultation; Interaction: Community Level | Craftspeople felt that they can have a say on community matters [O5-1a] (+) Emotional: Perceived Control by participating in an inclusive community meeting as active citizens [O5-1b] (+) Behavioral: Community Participation and their ability to voice their opinions was cultivated [O5-1c] (+) Relational: Collaborative Competence |

| The artisan was invited to attend the co-design exhibition and give comments in the seminar (Case 2) [P5-2] Instrumentation: Channels of Evaluation & Diffusion; Participation: Level 2: Partnership; Interaction: Regional & National Levels | The artisan developed a sense of self-esteem [O5-2a] (+) Emotional: Perceived Competence by actively attending these activities as craft representative [O5-2b] (+) Behavioral: Social Participation The artisan drew from the works inspirations for Tiao Hua innovation [O5-2c] (+) Cognitive: Skill & Knowledge Development and gained access to larger interpersonal networks [O5-2d] (+) Relational: Co-Creation Network Building | |

| Co-design results were evaluated and diffused through diverse means (e.g., media, awards, and conferences) (Case1, 2) [P5-3] Instrumentation: Channels of Evaluation & Diffusion | Artisans critically realized the difficulties and opportunities of Tiao Hua development and its potential to community sustainability [O5-3a] (+) Cognitive: Critical Systems Thinking More governmental, social and industrial resources were gradually directed into local community [O5-3b] (+) Relational: Co-Creation Network Building | |

| Artisans were invited to varied workshops, conferences and exhibitions after the project (Case 1, 2) [P5-4] Participation: Level 1, 2: Consultation, Partnership; Interaction: Organizational, Regional, National & International Levels | Artisans’ self-efficacy was amplified [O5-4a] (+) Emotional: Perceived Competence Some artisans began to frequently use social media to diffuse their activities and works [O5-4b] (+) Behavioral: Creative Behaviors which was influenced by individual branding lectures [O5-4c] (+) Cognitive: Knowledge & Skill Development New social divisions were created between participants and non-participants [O5-4d] (−) Relational: Bridging Social Divisions |

References

- Rodrigues, M.; Menezes, I.; Ferreira, P.D. Validating the formative nature of psychological empowerment construct: Testing cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and relational empowerment components. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 46, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamenopoulos, T.; Lam, B.; Alexiou, K.; Kelemen, M.; Sousa, S.D.; Moffat, S.; Phillips, M. Types, obstacles and sources of empowerment in co-design: The role of shared material objects and processes. CoDesign 2021, 17, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Dumitru, A.; Cipolla, C.; Kunze, I.; Wittmayer, J. Translocal empowerment in transformative social innovation networks. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 955–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L. Social design as a creative device in developing countries: The case of a handcraft pottery community in Cambodia. Int. J. Des. 2016, 10, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ertner, M.; Kragelund, A.M.; Malmborg, L. Five Enunciations of Empowerment in Participatory Design. In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, New York, NY, USA, 29 November–3 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bjögvinsson, E.; Ehn, P.; Hillgren, P.A. Design things and design thinking: Contemporary participatory design challenges. Des. Issues 2012, 28, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCRIBD. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/191799251/From-engaging-to-empowering-people-a-set-of-co-design-experiments-with-a-service-design-perspective (accessed on 16 December 2013).

- Drain, A.; Shekar, A.; Grigg, N. Insights, solutions and empowerment: A framework for evaluating participatory design. CoDesign 2021, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaş, B.M.; Mäkelä, M. Craft Dynamics: Empowering Felt Making through Design. In Proceedings of the 7th Nordic Design Research Conference, Oslo, Norway, 15–17 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, B. Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism, 1st ed.; Arsenal Pulp Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, X.; Walker, S. Value direction: Moving crafts toward sustainability in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamidipudi, A. Constructing common knowledge: Design practice for social change in craft livelihoods in India. Des. Issues 2018, 34, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, F.W. Weaving with rush: Exploring craft-design collaborations in revitalizing a local craft. Int. J. Des. 2012, 6, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzarella, F.; Mitchell, V.; Escobar-Tello, C. Crafting sustainable futures. The value of the service designer in activating meaningful social innovation from within textile artisan communities. Des. J. 2017, 20, S2935–S2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Pel, B.; Weaver, P.; Dumitru, A.; Haxeltine, A.; Kemp, R.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Bauler, T.; Ruijsink, S.; et al. Transformative social innovation and (dis)empowerment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, J. Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1987, 15, 121–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Empowerment Theory: Psychological, Organizational, and Community Levels of Analysis. In Handbook of Community Psychology; Rappaport, J., Seidman, E., Eds.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Christens, B.D. Toward relational empowerment. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 50, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, P.W. Social power and forms of change: Implications for psychopolitical validity. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 36, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, J. Questioning Empowerment: Working with Women in Honduras, 1st ed.; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 1997; pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Boje, D.M.; Rosile, G.A. Where is the power in empowerment? Answers from Follet and Clegg. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2001, 37, 90–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, C.; Leiba-O’Sullivan, S. The power behind empowerment: Implications for research and practice. Hum. Relat. 1998, 51, 451–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drain, A.; Shekar, A.; Grigg, N. “Involve me and I’ll understand”: Creative capacity building for participatory design with rural Cambodian farmers. CoDesign 2019, 15, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.M.; Rosson, M.B. Participatory design in community informatics. Des. Stud. 2007, 28, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E.; Rizzo, F. Small projects/large changes: Participatory design as an open participated process. CoDesign 2011, 7, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.N.; Stappers, P.J. Probes, toolkits and prototypes: Three approaches to making in co-designing. CoDesign 2014, 10, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinsmann, M.; Valkenburg, R. Barriers and enablers for creating shared understanding in co-design projects. Des. Stud. 2008, 29, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirinen, A. The barriers and enablers of co-design for services. Int. J. Des. 2016, 10, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Del-Gaudio, C.; Franzato, C.; Oliveira, A. Sharing design agency with local partners in participatory design. Int. J. Des. 2016, 10, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.S.; Ji, T.; Yang, Y.Y. The Potential of Rural Crafts in Promoting Community Empowerment through Participatory Design Intervention. In Proceedings of the Cumulus Association Biannual International Conference, Nottingham, UK, 27 April–1 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Suib, S.S.S.B.; Van Engelen, J.M.L.; Crul, M.R.M. Enhancing knowledge exchange and collaboration between craftspeople and designers using the concept of boundary objects. Int. J. Des. 2020, 14, 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, O.V.; Pazarbasi, C.K. Just craft: Capabilities and empowerment in participatory craft projects. Des. Issues 2018, 34, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heron, J.; Reason, P. The practice of co-operative inquiry: Research “with” people, rather than “on” people. In Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, 1st ed.; Reason, P., Bradbury, H., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2001; pp. 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, E.B.N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauenberger, C.; Good, J.; Fitzpatrick, G.; Iversen, O.S. In pursuit of rigor and accountability in participatory design. Int. J. Hum. Comput. 2015, 74, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, M.; Sclater, M. Creating spaces for collaboration in community co-design. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2021, 40, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, M.; Ramachandran, D.; Raghavan, A.; Chiu, J.; Sahni, U.; Canny, J. Practical Considerations for Participatory Design with Rural School Children in Underdeveloped Regions: Early Reflections from the Field. In Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Interaction Design and Children, New York, NY, USA, 7–9 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. The Craftsman, 1st ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008; pp. 149–178. [Google Scholar]

- Deeley, S.J.; Bovill, C. Staff student partnership in assessment: Enhancing assessment literacy through democratic practices. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.C.; Hoven, E.V.D. Memory probes: Exploring retrospective user experience through traces of use on cherished objects. Int. J. Des. 2018, 12, 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rabadjieva, M.; Butzin, A. Emergence and diffusion of social innovation through practice fields. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, A. Design activism in an Indonesian village. Des. Issues 2019, 35, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, M.; Tessier, V.; Hawey, D. Understanding collaborative design through activity theory. Des. J. 2017, 20, S4611–S4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plann. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Getha-Taylor, H. Identifying collaborative competencies. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2008, 28, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Yagiz, B.Y. Design in informal economies: Craft neighborhoods in Istanbul. Des. Issues 2011, 27, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E.; M’Rithaa, M.K. Distributed systems and cosmopolitan localism: An emerging design scenario for resilient societies. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Improvement through Iteration | Case 1 | Case 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Adoption of New Materials | Acrylic Plastic (e.g., the raincoat with Tiao Hua) | Wood (e.g., the wooden box package with Tiao Hua); Ceramic (e.g., ceramic necklaces with Tiao Hua) |

| Craft Combination | Tiao Hua + Bamboo Craft (e.g., the bamboo handbag with Tiao Hua) | Tiao Hua + Indigo Dyeing (e.g., the indigo bag with Tiao Hua); Tiao Hua + Lacquer Painting (e.g., decorations) |

| Technology Appropriation | Adding Tiao Hua appliqués to new materials (e.g., the acrylic raincoat) | Applying Tiao Hua directly to new materials (e.g., ceramic, wood) aided by auxiliary drawings; Creating 3D Tiao Hua |

| Cultural Appropriation | Tiger motifs (e.g., shoes with tiger motifs symbolizing a strong person walking as vigorously as a tiger) | Tiger motifs (e.g., infant costume wishing the baby as robust as a tiger); a motif of half-dragon and half-carp (e.g., a baby sling symbolizing parents’ high hopes for their child) |

| Stakeholders | S1 (Knowledge Acquisition) | S2 (Concept Generation) | S3 (Preliminary Prototyping) | S4 (Hand- Crafting) | S5 (Evaluation & Diffusion) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Artisans | L1 | L0 | L0 | L2, L3 | L1 |

| Designers | L2, L3 | L3 | L3 | L0, L1 | L2, L3 | |

| Others | L1, L2 1 | L0 | L1 2 | L0 | L1, L2 3 | |

| Case 2 | Artisans | L1, L2 | L1 | L0 | L0, L1 | L1, L2 |

| Designers | L2, L3 | L3 | L2, L3 | L3 | L2, L3 | |

| Others | L0, L1 1 | L0 | L1, L2 4 | L0 | L1 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Ji, T.; He, R. Empowerment or Disempowerment: The (Dis)empowering Processes and Outcomes of Co-Designing with Rural Craftspeople. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054468

Wang B, Ji T, He R. Empowerment or Disempowerment: The (Dis)empowering Processes and Outcomes of Co-Designing with Rural Craftspeople. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054468

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Baosheng, Tie Ji, and Renke He. 2023. "Empowerment or Disempowerment: The (Dis)empowering Processes and Outcomes of Co-Designing with Rural Craftspeople" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054468

APA StyleWang, B., Ji, T., & He, R. (2023). Empowerment or Disempowerment: The (Dis)empowering Processes and Outcomes of Co-Designing with Rural Craftspeople. Sustainability, 15(5), 4468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054468