Financial Well-Being in the United States: The Roles of Financial Literacy and Financial Stress

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Financial Well-Being

2.2. Financial Literacy

2.3. Financial Education

2.4. Financial Stress

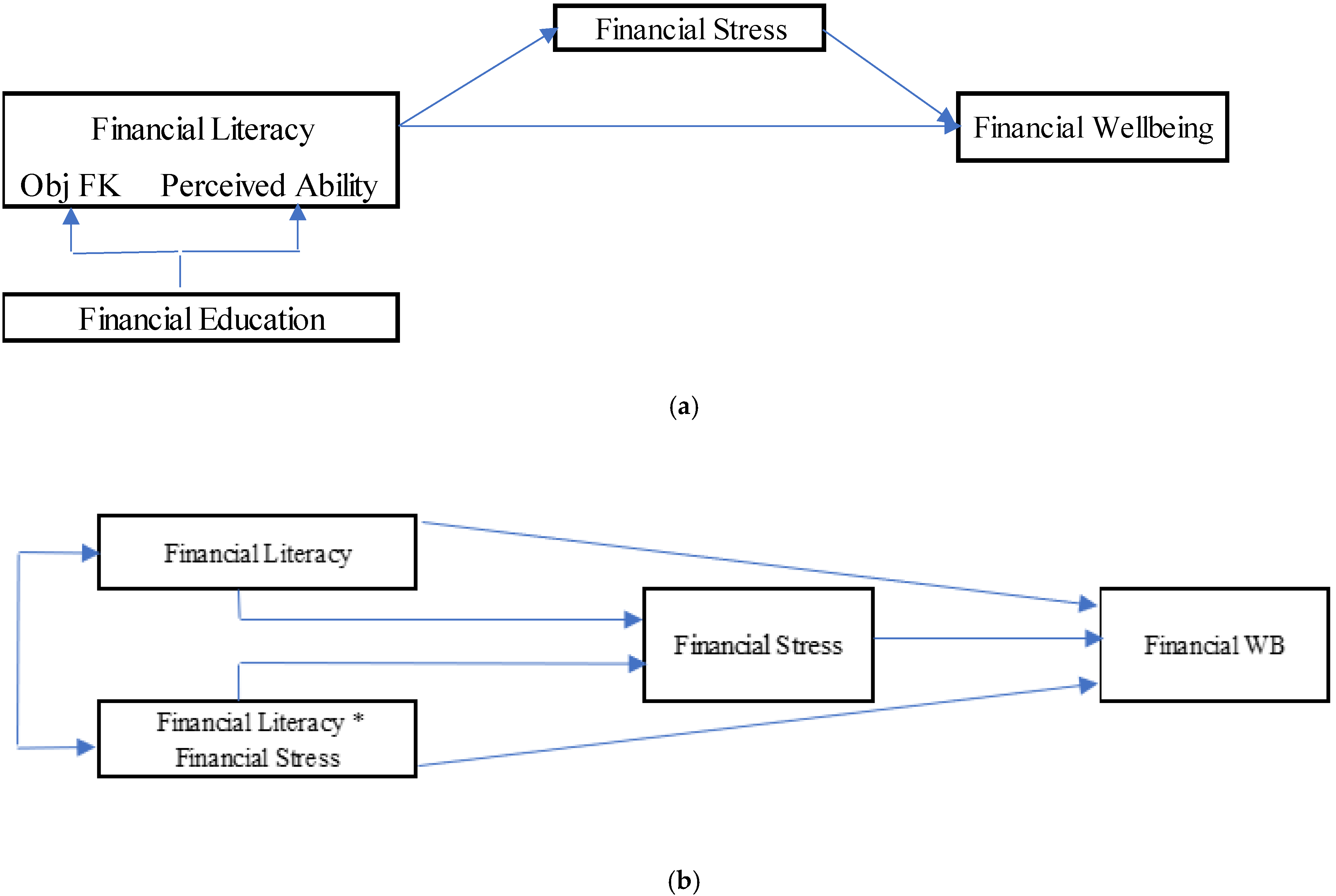

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Financial Literacy and Financial Well-Being

3.2. Mediating Role of Financial Stress

3.3. Theoretical Elaboration of Behavioral Finance

4. Methods

4.1. Data

4.2. Dependent Variables

4.2.1. Financial Well-Being

4.2.2. Financial Literacy

4.2.3. Financial Stress

4.3. Independent Variables

Financial Education

4.4. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

4.5. Empirical Model Specification

4.6. Mediation Analysis

4.7. Moderated Mediation Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Factors Associated with Financial Literacy

5.3. Mediation Analysis

5.3.1. Financial Stress and Financial Literacy

5.3.2. Financial Literacy and Financial Well-being Mediated by Financial Stress

5.3.3. Moderated Mediation Model of Financial Literacy, Financial Stress, and Financial Well-Being

6. Discussion and Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. J. Econ. Lit. 2014, 52, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munnukka, J.; Uusitalo, O.; Koivisto, V.J. The consequences of perceived risk and objective knowledge for consumers’ investment behavior. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2017, 22, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Advancing National Strategies for Financial Education. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-education/G20_OECD_NSFinancialEducation.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Kozup, J.; Hogarth, J.M. Financial literacy public policy and consumer’s self-protection–more questions, fewer answers. J. Consum. Aff. 2008, 42, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jappelli, T. Economic literacy: An international comparison. Econ. J. 2010, 120, F429–F451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nolan, A.; Doorley, K. Financial Literacy and Preparation for Retirement; IZA Discussion Paper No. 12187; IZA: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, S.; Lim, H.; Montalto, C. Factors related to financial stress among college students. J. Financ. Ther. 2014, 5, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chu, C.; Buchman-Schmitt, J.M.; Stanley, I.H.; Hom, M.A.; Tucker, R.P.; Hagan, C.R.; Rogers, M.L.; Podlogar, M.C.; Chiurliza, B.; Ringer, F.B.; et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 1313–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippas, N.D.; Avdoulas, C. Financial literacy and financial well-being among generation-Z university students: Evidence from Greece. Eur. J. Financ. 2019, 26, 360–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Available online: https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201501_cfpb_report_financial-well-being.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Fan, L.; Henager, R. A structural determinants framework for financial well-being. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 43, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, W. Are we happy yet? Financ. Plan. 2004, 34, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, S.; Grable, J.E. An exploratory framework of the determinants of financial satisfaction. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2004, 25, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hira, T.K.; Mugenda, O.M. Predictors of financial satisfaction: Differences between retirees and nonretirees. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 1998, 9, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sass, S.A.; Belbase, A.; Cooperrider, T.; Ramos-Mercado, J.D. Available online: https://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/wp_2015-3.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Shim, S.; Xiao, J.J.; Barber, B.L.; Lyons, A.C. Pathways to life success: A conceptual model of financial well-being for young adults. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 30, 708–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugenda, O.M.; Hira, T.K.; Fanslow, A.M. Assessing the causal relationship among communication, money management practices, satisfaction with financial status, and satisfaction with quality of life. Lifestyles Fam. Econ. Issues 1990, 11, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.J.; Chen, C.; Chen, F. Consumer financial capability and financial satisfaction. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, C.A.; Chatterjee, S.; Porto, N.; Cude, B. The influence of student loan debt on financial satisfaction. J. Fam. Issues 2019, 40, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Fan, L. Older adults’ life satisfaction: The roles of seeking financial advice and personality traits. J. Financ. Ther. 2021, 12, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutter, M.; Copur, Z. Financial behaviors and financial well-being of college students: Evidence from a National Survey. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2011, 32, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; McKinney, L.; Hagedorn, L.S.; Purnamasari, A.; Martinez, F.S. Stretching every dollar: The impact of personal financial stress on the enrollment behaviors of working and nonworking community college students. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2017, 41, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starobin, S.S.; Hagedorn, L.S.; Purnamasari, A.; Chen, Y.A. Examining financial literacy among transfer and nontransfer students: Predicting financial well-being and academic success at a four-year university. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2013, 37, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalgn, G.; Tangl, A. Forecasting green financial innovation and its implications for financial performance in Ethiopian Financial Institutions: Evidence from ARIMA and ARDL model. Natl. Account. Rev. 2022, 4, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, J.J.; Zhang, W. Financial literacy, portfolio choice and financial well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 799–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Failler, P.; Liu, Z. Impact of environmental regulations on energy efficiency: A case study of China’s air pollution prevention and control action plan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Failler, P.; Ding, Y. Enterprise financialization and technological innovation: Mechanism and heterogeneity. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Palmer, L.; Goetz, J. Sustainable withdrawal rates of retirees: Is the recent economic crisis a cause for concern? Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2011, 3, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hansen, T.; Slagsvold, B.; Moum, T. Financial satisfaction in old age: A satisfaction paradox or a result of accumulated wealth? Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 89, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, S.M.; Sharma, E. Consumer wealth. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 5, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Literacy and Education Commission. Available online: https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/financial-education/Documents/NationalStrategyBook_12310%20(2).pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- OECD. Improving Financial Literacy: Analysis of Issues and Policies. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/document/28/0,3343,en_2649_15251491_35802524_1_1_1_1,00.html (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O. Financial literacy around the world: An overview. J. Pension Econ. Financ. 2011, 10, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klapper, L.; Lusardi, A.; Van Oudheusden, P. Financial Literacy around the World. Available online: https://gflec.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Finlit_paper_16_F2_singles.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Huston, S.J. Measuring financial literacy. J. Consum. Aff. 2010, 44, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Literacy Canada. Available online: http://financialliteracyincanada.com/definition.html (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- FINRA. Investor Education Foundation. Available online: https://www.usfinancialcapability.org/downloads.php (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Xiao, J.J.; O’Neill, B. Consumer financial education and financial capability. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerrans, P.; Heaney, R. The impact of undergraduate personal finance education on individual financial literacy, attitudes and intentions. Account. Financ. 2019, 59, 177–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Chatterjee, S. Application of situational stimuli for examining the effectiveness of financial education: A behavioral finance perspective. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2018, 17, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Lu, J.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Bissielou, H. Sustainable financial education and consumer life satisfaction. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urban, C.; Schmeiser, M.; Collins, J.M.; Brown, A. The effects of high school personal financial education policies on financial behavior. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2018, 78, 101786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernheim, B.D.; Garrett, D.M. The effects of financial education in the workplace: Evidence from a survey of households. J. Public Econ. 2003, 87, 1487–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Workplace financial education. In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research; Xiao, J.J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Robb, C.A. College student financial stress: Are the kids alright? J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2017, 38, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Silva, R.; Franco, M. COVID-19: Financial Stress and Well-Being in Families. J. Fam. Issues 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rania, N.; Coppola, I.; Brucci, M. Mental health and quality of professional life of healthcare workers: One year after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fietta, V.; Bertoldo, F.; Gasperi, L.; Mazza, C.; Roma, P.; Monaro, M. The role of work engagement in facing the COVID-19 pandemic among mental healthcare workers: An Italian study to improve work sustainability during emergency situations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grable, J.; Heo, W.; Rabbani, A. Financial anxiety, physiological arousal, and planning intention. J. Financ. Ther. 2014, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Garman, E.T. Financial stress, pay satisfaction and workplace performance. Compens. Benefits Rev. 2004, 36, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.L.; Heo, W.; Cho, S.H.; Lee, P. The links between job insecurity, financial well-being and financial stress: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, K.; Stewart, S.D.; Wilson, J.; Korsching, P.F. Perceptions of financial well-being among American women in diverse families. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2010, 31, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Isa, C.R.; Masud, M.M.; Sarker, M.; Chowdhury, N.T. The role of financial behaviour, financial literacy, and financial stress in explaining the financial well-being of B40 group in Malaysia. Future Bus. J. 2021, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, J.E.; Ingersoll, J.E. Theory of Financial Decision Making; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 1987; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Thaler, R.H. Anomalies: Utility maximization and experienced utility. J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/theory-consumption-function/permanent-income-hypothesis (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Ando, A.; Modigliani, F. The “life-cycle” hypothesis of saving aggregate implications and tests. Am. Econ. Rev. 1963, 53, 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Fan, L. Financial capability, financial education, and student loan debt: Expected and unexpected results. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2022, 33, 324–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, K.M.; Evans, S.B.; McCorkle, R.; DiGiovanna, M.P.; Pusztai, L.; Sanft, T.; Hofstatter, E.W.; Killelea, B.K.; Knobf, M.T.; Lannin, D.R.; et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014, 10, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robb, C.A.; Woodyard, A. Financial knowledge and best practice behavior. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2011, 22, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, H.H.; LeBaron, A.B.; Hill, E.J. Family matters: Decade review from journal of family and economic issues. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 42, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.H. Rethinking rational choice. In Beyond the Marketplace; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 53–87. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, F.H. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1921; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Blavatskyy, P.R. Stochastic expected utility theory. J. Risk Uncertain. 2007, 34, 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thaler, R. Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1980, 1, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remund, D.L. Financial literacy explicated: The case for a clearer definition in an increasingly complex economy. J. Consum. Aff. 2010, 44, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yzerbyt, V.Y.; Muller, D.; Judd, C.M. Adjusting researchers’ approach to adjustment: On the use of covariates when testing interactions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 40, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderweele, T.J. A Unification of Mediation and Interaction. Epidemiology 2014, 25, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bayer, P.J.; Bernheim, B.D.; Scholz, J.K. The effects of financial education in the workplace: Evidence from a survey of employers. Econ. Inq. 2009, 47, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hira, T.; Loibl, C. Understanding the impact of employer-provided financial education on workplace satisfaction. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nareswari, N.; Negoro, N.P.; Dalem, G.D.W. Mitigating personal financial distress: The role of religiosity and financial literacy. Procedia Bus. Financ. Technol. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | St. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWB | 54.922 | 14.743 | 22 | 87 |

| Fin Literacy | ||||

| Obj_FinK | 3.116 | 1.687 | 0 | 6 |

| Sub_FinK | 5.127 | 1.354 | 1 | 7 |

| Fin_Cap | 5.759 | 1.527 | 1 | 7 |

| Finconfident | 3.035 | 0.875 | 1 | 4 |

| Fin Educ | ||||

| Hours Finedu | 2.489 | 0.704 | 1 | 3 |

| Schsetedu | 0.397 | 0.489 | 0 | 1 |

| Worksetedu | 0.359 | 0.480 | 0 | 1 |

| Fin Stress | 13.118 | 5.489 | 3 | 21 |

| SocioDemog | ||||

| Age18to24 | 0.103 | 0.304 | 0 | 1 |

| Age25to34 | 0.173 | 0.378 | 0 | 1 |

| Age35to44 | 0.167 | 0.373 | 0 | 1 |

| Age45to54 | 0.172 | 0.378 | 0 | 1 |

| Age55to64 | 0.181 | 0.385 | 0 | 1 |

| Age65oldr | 0.203 | 0.403 | 0 | 1 |

| Male | 0.441 | 0.497 | 0 | 1 |

| White | 0.742 | 0.438 | 0 | 1 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single | 0.297 | 0.457 | 0 | 1 |

| Married | 0.534 | 0.499 | 0 | 1 |

| Divornsep | 0.126 | 0.331 | 0 | 1 |

| Widowed | 0.044 | 0.205 | 0 | 1 |

| Hasdepen | 0.355 | 0.478 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | ||||

| HSlow | 0.277 | 0.448 | 0 | 1 |

| Somecol | 0.268 | 0.443 | 0 | 1 |

| Coldegr | 0.324 | 0.468 | 0 | 1 |

| Pstgd | 0.131 | 0.337 | 0 | 1 |

| Income | ||||

| USD15k | 0.112 | 0.316 | 0 | 1 |

| USD15k_25k | 0.104 | 0.305 | 0 | 1 |

| USD25k_35k | 0.108 | 0.311 | 0 | 1 |

| USD35k_50k | 0.145 | 0.352 | 0 | 1 |

| USD50k_75k | 0.194 | 0.396 | 0 | 1 |

| USD75k_100k | 0.142 | 0.349 | 0 | 1 |

| USD100k_150k | 0.127 | 0.333 | 0 | 1 |

| USD150kab | 0.068 | 0.252 | 0 | 1 |

| Coef. | SE | Sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fin Educ | Hours Finedu | 0.3563 | 0.0443 | *** |

| Schsetedu | 0.5262 | 0.0662 | *** | |

| Worksetedu | 0.5773 | 0.0651 | *** | |

| Socio Demog | Educ (Ref: Hslow) | |||

| Somecol | 0.8186 | 0.1032 | *** | |

| Coldegr | 1.0387 | 0.1017 | *** | |

| Pstgd | 1.3299 | 0.1222 | *** | |

| Income (Ref: USD15k) | ||||

| USD15k_25k | 0.1551 | 0.1468 | ||

| USD25k_35k | 0.4710 | 0.1450 | *** | |

| USD35k_50k | 1.0649 | 0.1317 | *** | |

| USD50k_75k | 1.2125 | 0.1287 | *** | |

| USD75k_100k | 1.6448 | 0.1347 | *** | |

| USD100k_150k | 1.8020 | 0.1394 | *** | |

| USD150kab | 2.2015 | 0.1588 | *** | |

| Male | 0.6605 | 0.0621 | *** | |

| White | 0.1960 | 0.0688 | *** | |

| Married | 0.0239 | 0.0716 | ||

| Has Dependent | −0.2657 | 0.0712 | *** | |

| Age (Ref: Age 18 to 24) | ||||

| Age 25 to 34 | 0.2544 | 0.1067 | ** | |

| Age 35 to 44 | 0.2217 | 0.1145 | ||

| Age 45 to 54 | 0.4449 | 0.1146 | *** | |

| Age 55 to 64 | 0.9548 | 0.1181 | *** | |

| Age 65 oldr | 1.4806 | 0.1215 | *** | |

| Intercept | −2.2859 | 0.1701 | *** |

| Fin Stress | Fin Well-Being | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coef. | SE | Sig | Coef. | SE | Sig |

| Fin Literacy | −0.718 | 0.013 | *** | 1.224 | 0.026 | *** |

| Finstress | −1.564 | 0.012 | *** | |||

| Some Col | 0.825 | 0.086 | *** | −1.141 | 0.158 | *** |

| Col Deg | 0.529 | 0.085 | *** | −0.675 | 0.156 | *** |

| Pst Grad | 0.678 | 0.112 | *** | −1.199 | 0.206 | *** |

| USD15k_25k | 0.583 | 0.142 | *** | −0.068 | 0.260 | |

| USD25k_35k | 0.444 | 0.142 | *** | 1.533 | 0.259 | *** |

| USD35k_50k | 0.172 | 0.135 | 2.916 | 0.247 | *** | |

| USD50k_75k | −0.256 | 0.132 | 4.551 | 0.242 | *** | |

| USD75k_100k | −0.195 | 0.143 | 6.105 | 0.262 | *** | |

| USD100k_150k | −0.872 | 0.150 | *** | 7.156 | 0.274 | *** |

| USD150kab | −2.080 | 0.175 | *** | 9.029 | 0.320 | *** |

| Male | −0.687 | 0.064 | *** | −1.050 | 0.117 | *** |

| White | 0.355 | 0.224 | 0.136 | 0.865 | ||

| Married | −0.173 | 0.073 | ** | 0.671 | 0.134 | *** |

| DepChild | 0.987 | 0.075 | *** | −1.658 | 0.914 | *** |

| Age25to34 | 1.106 | 0.129 | *** | −1.637 | 0.936 | |

| Age35to44 | 0.708 | 0.131 | *** | −2.170 | 1.240 | |

| Age45to54 | 0.584 | 0.129 | *** | −2.164 | 2.235 | |

| Age55to64 | −0.326 | 0.129 | ** | 1.239 | 1.236 | |

| Age65oldr | −1.894 | 0.130 | *** | 1.546 | 1.239 | |

| Intercept | 12.798 | 0.148 | *** | 74.869 | 0.310 | *** |

| Outcome | Treatment | Mediator | Total Effect | ACME | % Mediated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWB | Fin Literacy | Fin Stress | 2.375 | 1.226 | 0.516 |

| DV: FWB | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coef. | SE | Sig |

| Fin Literacy | 1.668 | 0.058 | *** |

| Fin Stress | −1.543 | 0.012 | *** |

| FL*FS | −0.031 | 0.004 | *** |

| Other Controls | YES | ||

| Intercept | 74.487 | 0.313 | *** |

| Outcome | Treatment | Mediator | Interaction | TE | DE | INTref | INTmed | NIE | Average Mediation | Average Direct Effect | % Mediated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWB | Fin Literacy | Fin Stress | Fin Literacy × Fin Stress | 2.381 | 1.275 | 1.252 | 1.128 | 1.106 | 1.117 | 1.263 | 0.469 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Chatterjee, S. Financial Well-Being in the United States: The Roles of Financial Literacy and Financial Stress. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054505

Zhang Y, Chatterjee S. Financial Well-Being in the United States: The Roles of Financial Literacy and Financial Stress. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054505

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yu, and Swarn Chatterjee. 2023. "Financial Well-Being in the United States: The Roles of Financial Literacy and Financial Stress" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054505

APA StyleZhang, Y., & Chatterjee, S. (2023). Financial Well-Being in the United States: The Roles of Financial Literacy and Financial Stress. Sustainability, 15(5), 4505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054505