1. Introduction

Based on the concept of “open innovation”, enterprises’ innovation activities gradually integrate into diversified external subjects, fully absorb their knowledge in the innovation process, and carry out collaborative innovation to improve innovation performance [

1,

2]. The increasingly severe market competition also makes enterprises rely more and more on customers in external diversified innovation subjects. In collaborative innovation, enterprises frequently invite customers to participate in value co-creation [

3].

The essence of the cooperative innovation paradigm between enterprises and customers is the value of co-creation, reflecting the interactive innovation paradigm of enterprise–customer collaborative innovation. The research object of this paper is knowledge-intensive business service (KIBS) enterprises. The existence of KIBS enterprise-specific investment and the gradual transfer of professional knowledge ownership in the later stage of collaborative innovation induce the opportunistic behavior of organizational customers, as proven in the literature. Relevant studies have found that organizational customer cooperative innovation brings advantages to KIBS enterprises and heightens opportunistic behaviors in the cooperation process, which will increase cooperation costs for both parties and even the rupture of cooperative relations between organizations [

4]. Therefore, KIBS enterprises and organizational customers conduct cooperative innovation activities through value co-creation, and the negative impact cannot be ignored.

It is inevitable for enterprises to carry out business activities without developing a personal relationship between boundary personnel of enterprises on both sides in the Chinese business environment [

5]. Personal relationships between boundary personnel developed in collaborative innovation between KIBS enterprises and organizational customers will promote trust and cooperation between enterprises, effectively enhancing mutual commitment [

6]. Furthermore, they can restrain the probability of opportunistic behaviors such as speculation and retaliation in collaborative innovation. On the other hand, close personal relationships between the boundary personnel of both enterprises make them more likely to form a conspiracy to pursue private interests, creating a hotbed of corruption [

7], thus inducing opportunistic behaviors of enterprises in the process of collaborative innovation. It shows a “double-edged sword effect” when KIBS enterprises and customers conduct collaborative innovation [

8].

Still, few empirical studies have discussed under what circumstances personal relationships between boundary personnel of enterprises will restrain opportunism behavior or have an induced effect. The existing literature found that the effects on opportunism behavior related to personal relationships between the boundary personnel of enterprises engaged in cooperation innovation are relatively small. There is little research into the personal relationships between boundary personnel of enterprises and the specific mechanism of action of enterprise opportunism behavior. The literature also mainly involves theory or case analysis [

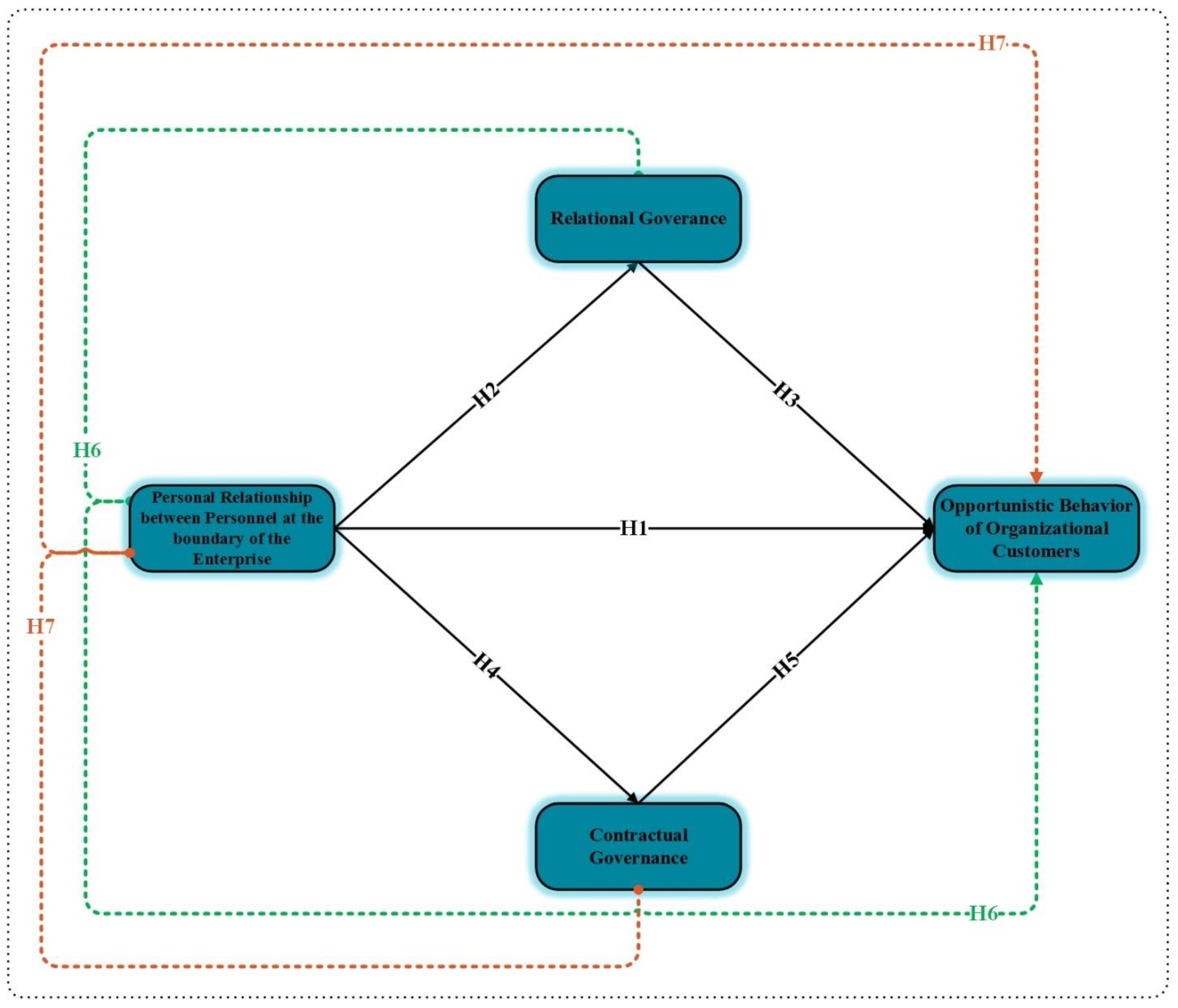

8] and lacks substantial empirical studies. Therefore, to make up for the shortcomings of the prior research, this study chiefly focuses on three research questions: (1) How does the personal relationship between KIBS enterprises and administrative customer boundary personnel affect organizational customer opportunistic behavior in collaborative innovation?; (2) What is the effect of introducing relationship governance and contract governance to specifically analyze the personal relationship between boundary personnel in influencing the opportunistic behavior of organizational customers?; and (3) Is there a double-edged sword effect in this mechanism?

The study is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the study background and hypotheses development.

Section 3 illustrates the research methodology and

Section 4 demonstrates the study results. Furthermore,

Section 5 discusses the results considering previous findings. Lastly, the study limitation and future direction, followed by the conclusion section, are explained at the end.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Study Procedure and Participants

Sample data were collected for cooperative innovation projects of KIBS enterprises from April 2022 to July 2022. The study explores four types of KIBS enterprises: (1) the financial industry in the Yangtze River delta (including banks, securities, insurance, and other financial activities of enterprises), (2) information and communication services (including telecommunications, software, computer services, and other communication services), (3) the science and technology service industry (including research and development, professional and technical services, engineering and planning management, science and technology exchange, and promotion services), and (4) the business service industry (specifically including legal service, consulting and survey, and other business services).

The respondents are mainly executives or leaders of cooperative innovation projects who are relatively familiar with the actual operating conditions of enterprises. With the help of friends, a combination of telephone appointments, home visits, and mailing questionnaires was used for data collection. Further, to adhere to the ethical concerns, participants were assured of their anonymity; they filled the questionnaires as and when they wished. In this study, 550 questionnaires were distributed, and 470 were received from the participants. Two philosophies were adhered to in processing the recovered questionnaires. First, some questionnaires were incomplete, with only some items filled in. If only some item’s data were missing, the mean value of this item was used to replace the missing data; if there were many missing items, they were directly treated as invalid questionnaires and abandoned. Second, the seriousness of the questionnaire respondents was checked. The questionnaire was considered invalid if most of the items or all items had the same score. After excluding the abandoned and invalid questionnaires, the number of the actual valid questionnaires was 449, with an effective recovery rate of 81.6%. The effective questionnaires collected in the early stage were compared with those collected in the later stage, and it was found that there was no significant difference. Therefore, it can be considered that there was no influence of non-response bias in the survey samples.

Table 1 shows the study’s descriptive statistics.

3.2. Measures

To ensure the validity and reliability of the measurement, previously developed scales were used to measure the four variables (personal relationship between personnel at the boundary of the enterprise, relational governance, contractual governance, and opportunistic behavior of organizational customers). The five-point Likert scale was used in the questionnaire, in which “1” means completely inconsistent, “2” means not consistent, “3” means uncertain, “4” means relatively consistent, and “5” means completely consistent.

In this study, organizational customer opportunism behavior scale items are adapted from the study of Samaha et al. [

47] and Gundlach et al. [

48]. There are eight measurement items, such as “customer enterprises often exaggerate to achieve their goals.” The personal relationship between personnel at the boundary of enterprises scale items was adapted from the study of Lee and Dawes [

49] and Zhuang et al. [

50], which can be summarized into nine measurement questions, such as “we often have opportunities to contact with customer enterprises, such as having dinner together or participating in certain activities.”

Relationship governance was measured on the 14 items scale, adapted from Heide’s study [

51]. The sample items include “my company and customer enterprises trust each other.” Contractual governance was measured on the six items scale adapted from the study of Lusch and Brown [

52] and Li et al. [

53]; the sample items include “our company and client enterprises have very detailed agreements in business activities.”

3.3. Statistical Approach

SPSS (version 24.0) statistical software was used to analyze the data reliability, while PLS-SEM software was used for hypothesis testing and factor loading. The data was statistically analyzed by using the regression analysis methods.

5. Discussion

By evaluating the effect of the personal relationship on opportunistic behavior in collaborative innovation, this study reexamined the literature on innovation personal relationships between boundary personnel of knowledge-intensive business service (KIBS) enterprises. Furthermore, the study determined the cost-effective role of a governance mechanism in curbing opportunistic behavior. Fundamentally, in this regard, this inherent section presents the research findings in light of the previous literature. This study adopted the empirical research method based on KIBS enterprises’ cooperative innovation projects with organizational customers in China. This study adopted the theory of inter-organizational relationships to explore the influence of the personal relationship between employees at the boundary of enterprises on organizational customers’ opportunistic behavior and profoundly analyze the mediating effect of relationship governance and contract governance.

In the process of cooperation innovation [

55], the personal relationship between the enterprises raises trust and commitment among the parties. It provides a mutual economic benefit to both sides. However, in addition to this, Mercado and Vargas-Hernández [

56] suggest that the personal relationship increases the uncertainty in information, thus illustrating a rise in organizational customer opportunistic behavior. Opportunistic behavior is a significant barrier to firms’ innovation. It may increase the transaction cost and hinder the firms’ collaborative relationship development. As a result of the information distortion, the opportunistic behavior explicitly engages the customer enterprise to focus on their self-interest, thus demanding the need for effective governance [

57]. In this regard, this study states that the closer the personal relationships between boundary personnel will lead to collaborative innovation [

58].

Previous studies have effectively examined the role of personnel relationship governance and contract governance in knowledge innovation acquisition and opportunistic behavior. According to Hadj [

29], enterprises form a relationship based on norms and values in the personal relationship, thus accelerating opportunistic behavior. Moreover, Zhigang et al. [

8] also contend that the low efficiency of law enforcement creates conditions that hinder the effective implementation of collaborative innovation on both sides. Enterprises have chosen to adopt contract governance to restrain the opportunistic behavior of enterprises for collaborative innovation [

59]. Moreover, this study shows that when there is a close personal relationship between the border personnel of the cooperative enterprises of both parties [

39], the corresponding employees of KIBS enterprises will likely influence their enterprises to relax the formal monitoring of the other enterprise under the banner of relationship governance while secretly colluding with the speculative behavior of customers. Its real purpose is to seek improper personal interests at the expense of the legitimate interests of the enterprise. Hence, by comparing the study results with the previous literature, we have concluded that all the hypotheses are consistent with the prior studies. Therefore, based on our findings, we accept and support the assumptions made in H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, and H7.

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

This study explored the “double-edged sword” effect of the personal relationship between boundary personnel on the opportunistic behavior of enterprises in collaborative innovation. The main focus of previous studies on collaborative innovation between enterprises and organizational customers was whether collaborative innovation would affect the innovation performance of enterprises. How does collaborative innovation affect enterprise innovation performance? How can collaboration with organizational customers improve innovation performance? However, transaction cost theory argues that organizational customers value and create value in a cooperative combination that extracts innovation. In the personal cooperation relation between the personnel of enterprise boundary and customers, there are always two sides to the coin. In the cooperation process, the two sides will produce certain opportunistic behavior, but studying this negative effect of collaborative innovation has been relatively rare. Therefore, this study theoretically expands the extension of cooperative innovation theory.

At present, researchers generally focus on the positive impact of a personal relationship between personnel at the boundary of enterprises on opportunistic behavior but pay less attention to its negative impact. There is a lack of in-depth discussion on the internal mechanism of such negative impact from an empirical perspective. This study verified the relationship between enterprises from the perspective of empirical management and contract management in the inhibition of opportunism behavior of the role of enterprises and also found that the enterprise will enhance the personal relationship between boundary personnel relationship norms and inhibit opportunism behavior. This may also lead to the relaxation of contract monitoring, contributing to the occurrence of customers’ opportunistic behavior. The exploratory findings of this study provide scientific evidence for the prediction of governance theory in inter-organizational relationship theory and indicate that it is necessary to take a contingency view toward the governance role of a personal relationship between boundary personnel on both sides in the process of collaborative innovation. This enriches the theory of governance mechanism in the theory of inter-organizational relations to a certain extent.

5.2. Practical Significance

Enterprises must be aware of opportunistic behavior between both sides when they carry out cooperative innovation activities with organizational customers. Therefore, enterprises must regulate the behaviors of both parties through explicit written agreements such as contracts, policies, and rules, as well as procedural procedures, such as detailed and comprehensive contract terms, to protect the vital interests of both parties through the legal effect of the contract. Enterprises can also use social norms, trust, values, and other relative recessive binding forces to develop and maintain the personal relationship between boundary personnel and other enterprises. Building trust, harmony, and tolerance in the personal relationship will be more beneficial to enhance enterprise resilience in the face of sudden emergencies.

The discovery of the “double-edged sword” effect of personal relationships between border personnel on enterprise opportunistic behavior in this study provides a reference for applying and developing the personal relationship between border personnel in collaborative innovation. Enterprises can effectively use contract or relationship governance to restrain opportunistic behavior in collaborative innovation. The more closely cooperative innovation in the enterprise can realize the personal relationship between boundary personnel, the more conducive their efforts will be to improving the strength of the relationship between corporate governance and further reducing the possibility of organization customer opportunism behavior. The closer the personal relationship between the personnel of the enterprise boundary, the more conducive it will be to improving the strength of the contractual governance between enterprises and thus further increasing the possibility of organizational customer opportunistic behavior. In the cooperation process, enterprises of both sides must attach great importance to this “double-edged sword” effect and make reasonable and effective use and arrangement of inter-organizational governance mechanisms.

5.3. Study Limitations and Future Directions

There are some shortcomings in this study. Firstly, the data were collected from the KIBS enterprises, so it is debatable whether the conclusions obtained in this study can be applied to the cooperative innovation process of other types of enterprises. For example, manufacturing enterprises also have cooperative innovation situations but may face different situations. Secondly, the data collected in this study were not random sample data and they were only the data of KIBS enterprises. Further, the sample size was collected from China and the coverage was not comprehensive, so the representativeness of the research conclusions may be limited to some extent. Thirdly, this study has no classified research on the four types of KIBS enterprises. However, personal relationships between employees may have different impacts on enterprise opportunism among different KIBS enterprises. Bilateral data should be collected from the two countries’ enterprises to make the conclusions more credible. Meanwhile, similar studies should be carried out on the collaborative innovation of manufacturing enterprises to expand the research.

6. Conclusions

The hypotheses and extracted results more specifically were as follows: (1) There is a positive correlation between the personal relationship of boundary personnel and organizational customer opportunistic behavior—that is, the closer the personal relationship between boundary personnel, the greater the probability of organizational customer opportunistic behavior; (2) the relationship governance and contract governance between enterprises can effectively restrain the opportunistic behavior of organizational customers; (3) relationship governance plays a partial mediating role between the personal relationship of employees at the boundary and the opportunistic behavior of organizational customers—that is, the closer the personal relationship between employees at the boundary, the more beneficial it is to improving the intensity of the relationship governance between enterprises, further reducing the probability of opportunistic behavior of organizational customers; (4) contract governance plays a mediating role between the personal relationship of employees at the boundary and the opportunistic behavior of organizational customers; and (5) the closer the personal relationship between employees at the boundary is, the more unfavorable it is to improve the intensity of contract governance between enterprises, further increasing the probability of opportunistic behavior of organizational customers.

The results show that the personal relationship between boundary personnel will increase the probability of corporate customer opportunism. Meanwhile, the relationship between governance and contract governance between enterprises can effectively restrain the opportunistic behavior of organizational customers. The personal relationship between boundary personnel will enhance the relationship norms and inhibit the opportunistic behavior of organizational customers, and relationship governance plays a partial intermediary role in this. The personal relationship between employees at an enterprise’s boundary will relax the contract’s supervision and encourage corporate customer opportunism, meaning contract governance also plays an intermediary role.