The Interest Shown by Potential Young Entrepreneurs in Romania Regarding Feasible Funding Sources, in the Context of a Sustainable Entrepreneurial Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Indicator | 31 July 2021 | 31 July 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| New registrations in the area of entrepreneurship | 91,400 | 90,126 |

2. Literature Review

2.1. Entrepreneurial Education and Sustainable Development

2.2. Sources of Funding

2.3. Sources of Funding

3. Research Method

3.1. Questionnaire Development

- RQ1. What is the level of knowledge possessed by the respondent in the field of entrepreneurship (part of sustainable entrepreneurial education entrepreneurship education)?

- RQ2. What are the main sources of financing known to the respondents?

- RQ3. What are the respondents’ attitudes and opinions regarding the different types of financing sources?

- RQ4. What is the future entrepreneurial intention regarding the establishment of a new business?

3.2. Data Collection, and Location of the Survey

3.3. Study Sample

3.4. Data Analysis Techniques

4. Results and Discussions

- RQ1. What is the level of knowledge possessed by the respondent in the field of entrepreneurship (part of sustainable entrepreneurial education entrepreneurship education)?

- RQ2. What are the main sources of financing known to the respondents?

- RQ3. What are the respondents’ attitudes and opinions regarding the different types of financing sources?

- RQ4. What is the future entrepreneurial intention regarding the establishment of a new business?

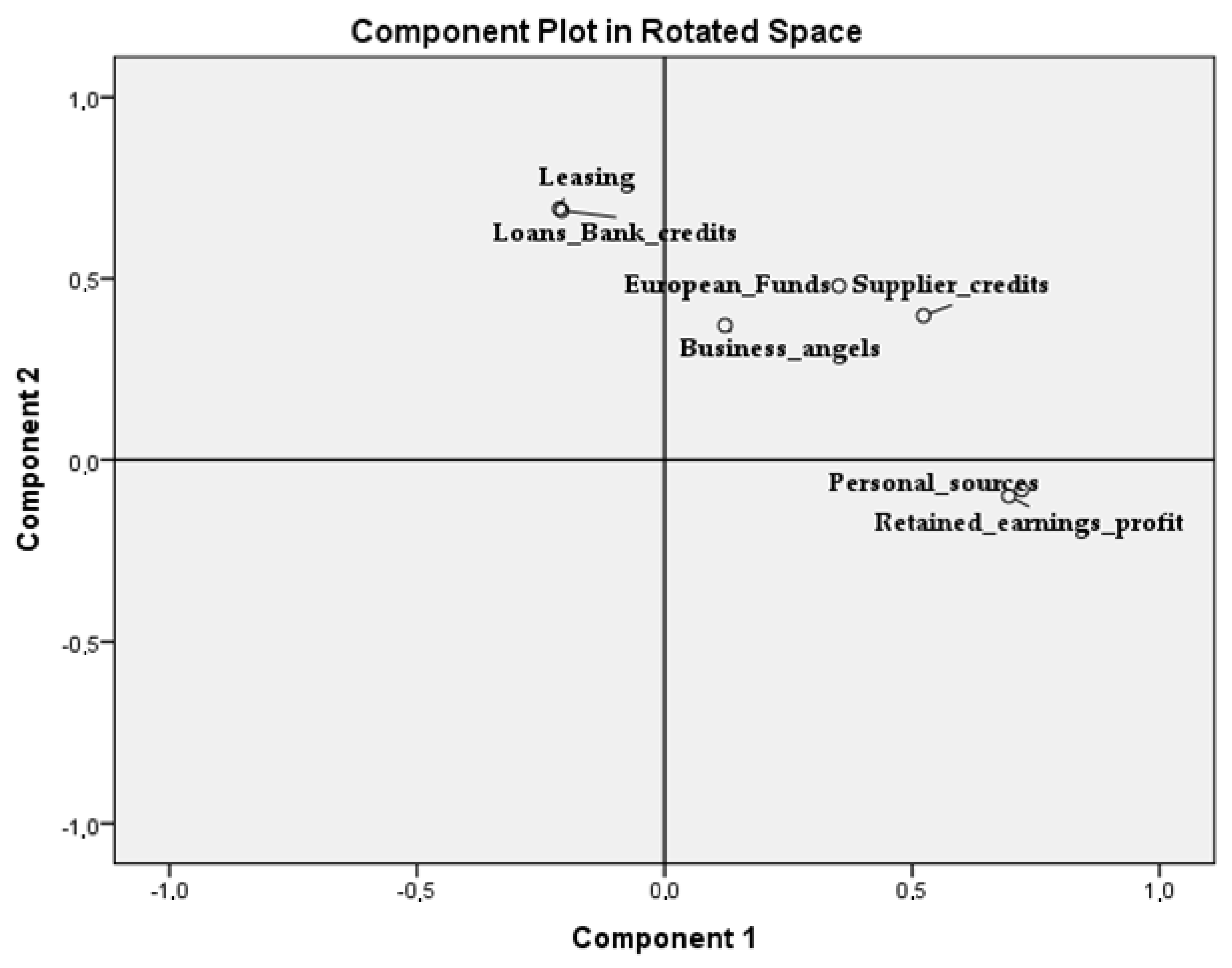

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Q14 | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To a Very Low Extent | 2 | 3 | 4 | To a Very High Extent | ||||

| Gender | Male | Count | 18 | 24 | 16 | 12 | 5 | 75 |

| Expected Count | 13.9 | 21.3 | 20.8 | 14.5 | 4.5 | 75.0 | ||

| Female | Count | 35 | 57 | 63 | 43 | 12 | 210 | |

| Expected Count | 39.1 | 59.7 | 58.2 | 40.5 | 12.5 | 210.0 | ||

| Total | Count | 53 | 81 | 79 | 55 | 17 | 285 | |

| Expected Count | 53.0 | 81.0 | 79.0 | 55.0 | 17.0 | 285.0 | ||

Appendix B

| Q18 | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disagree | Undecided | Agree | ||||

| Gender | Male | Count | 17 | 36 | 22 | 75 |

| Expected Count | 17.9 | 31.8 | 25.3 | 75.0 | ||

| Female | Count | 51 | 85 | 74 | 210 | |

| Expected Count | 50.1 | 89.2 | 70.7 | 210.0 | ||

| Total | Count | 68 | 121 | 96 | 285 | |

| Expected Count | 68.0 | 121.0 | 96.0 | 285.0 | ||

References

- Ministry of Investments and European Projects Sinteza Programelor Operaționale 2021–2027. Available online: https://mfe.gov.ro/sinteza-programelor-operationale-2021-2027/ (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- European Commission Report on an EU SME Referral Scheme. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-07/220628-report-sme-referral-scheme_en.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Etzkowitz, H.; Webster, A.; Gebhardt, C.; Terra, B.R.C. The Future of the University and the University of the Future: Evolution of Ivory Tower to Entrepreneurial Paradigm. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation THE 17 GOALS Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Cumming, D.; Groh, A.P. Entrepreneurial Finance: Unifying Themes and Future Directions. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 50, 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pticar, S. Financing as One of the Key Success Factors of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Creat. Knowl. Soc. 2016, 6, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Justice. National Trade Register Office Oficiul National al Registrului Comertului. Available online: https://www.onrc.ro/index.php/ro/statistici (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Kang, Q.; Li, H.; Cheng, Y.; Kraus, S. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Analysing the Status Quo. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2021, 19, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Turban, D.B.; Bhawe, N.M. The Effect of Gender Stereotype Activation on Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Goktan, A.B.; Gunay, G. Gender Differences in Evaluation of New Business Opportunity: A Stereotype Threat Perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langowitz, N.; Minniti, M. The Entrepreneurial Propensity of Women. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amway 2020 AGER Brochure. Available online: https://www.amwayglobal.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2020_AGER__Brochure_ENG1.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Amway 2018 AGER Brochure. Available online: https://www.amwayglobal.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Ager_2018_Brochure_Color.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Edokpolor, J.E. Entrepreneurship Education and Sustainable Development: Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Skills. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 14, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rădulescu, C.V.; Burlacu, S.; Bodislav, D.A.; Bran, F. Entrepreneurial Education in the Context of the Imperative Development of Sustainable Business. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P.; Secundo, G.; Mele, G.; Passiante, G. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Education for Circular Economy: Emerging Perspectives in Europe. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 2096–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Curriculum with Teaching Models on Sustainable Development of Entrepreneurial Mindset among Higher Education Students in China: The Moderating Role of the Entrepreneurial Climate at the Institution. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, L. Entrepreneurship Education and Sustainable Development Goals: A Literature Review and a Closer Look at Fragile States and Technology-Enabled Approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, E.E.; Lebedeva, T.E.; Prokhorova, M.P.; Shobonova, L.Y.; Bulganina, S.V. Youth Entrepreneurship: Motivational Aspects and Economic Effects. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci 2019, 272, 032129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokker, P.; Dallago, B. Introduction Economic Transformation and the Challenge of Youth Entrepreneurship in Central and Eastern Europe. In Youth Entrepreneurship and Local Development in Central and Eastern Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Karadzic, V.; Drobnjak, R.; Reyhani, M. Opportunities and Challenges in Promoting Youth Entrepreneurship in Montenegro. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Sci. Appl. Res. 2015, 8, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Frimanslund, T.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Oklevik, O. The Role of Finance in the Literature of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 372–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldhof, G.J.; Malin, H.; Johnson, S.K.; Porter, T.; Bronk, K.C.; Weiner, M.B.; Agans, J.P.; Mueller, M.K.; Hunt, D.; Colby, A.; et al. Entrepreneurship in Young Adults: Initial Findings from the Young Entrepreneurs Study. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 35, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, J. Mentoring Young Entrepreneurs: What Leads to Success. Int. J. Evid. Based Coach. Mentor. 2006, 4, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, K.; Sørensen, A. Coming of Age: Watching Young Entrepreneurs Become Successful. Labour Econ. 2022, 77, 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, M.; Zia, B. Stimulating Managerial Capital in Emerging Markets: The Impact of Business and Financial Literacy for Young Entrepreneurs; The World Bank. 2011. Available online: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/1813-9450-5642 (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Yoganandan, G. Challenges of Young Entrepreneurs. Asia Pac. J. Res. 2017, 1, 112–115. [Google Scholar]

- Boissin, J.-P.; Branchet, B.; Emin, S.; Herbert, J.I. Students and Entrepreneurship: A Comparative Study of France and the United States. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2009, 22, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazou, K.; Passas, I.; Garefalakis, A.; Kourgiantakis, M.; Xanthos, G. Youth’s Entrepreneurial Intention: A Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis of the Factors Influencing Greek HEI Students in Time of Crisis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, H.; Hundt, C.; Sternberg, R. What Makes Student Entrepreneurs? On the Relevance (and Irrelevance) of the University and the Regional Context for Student Start-Ups. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VOCEDplus. Youth Entrepreneurship|VOCEDplus, the International Tertiary Education and Research Database. Available online: https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A71599 (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Jakubczak, J. Youth Entrepreneurship Barriers and Role of Education in Their Overcoming-Pilot Study. Manag. Intellect. Cap. Manag. Innov. Sustain. Knowl. Learn. Incl. Soc. 2015, 1775–1782. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Youth-Entrepreneurship-Barriers-and-Role-of-in-Jakubczak/63fce59956d043b791ad1129ec493cc15ec5c638 (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Liu, X.; Lin, C.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, D. Research on the Effects of Entrepreneurial Education and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy on College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Hashim, N. Impact of Entrepreneurial Education on Entrepreneurial Intentions of Pakistani Students. J. Entrep. Bus. Innov. 2015, 2, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.; Lucy, C. Enhancing Entrepreneurial Education: Developing Competencies for Success. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temoor, A.; Sara, R.R.; Muhammad, F.; Shenzhen, M.B.; Valliappan, R.; Nida, N.; Imran, A.S. Entrepreneurial Intentions of Pakistani Students: The Role of Entrepreneurial Education, Creativity Disposition, Invention Passion & Passion for Founding. J. Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyaningsih, R.P.D.; Wibowo, A.; Saptono, A.; Narmaditya, B.S. Does Entrepreneurial Knowledge Influence Vocational Students’ Intention? Lessons from Indonesia. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2020, 8, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.; Haddock-Millar, J.; Sepulveda, L.; Sanyal, C.; Syrett, S.; Kaye, N.; Deakins, D. Chapter 7 The Role of Mentoring in Youth Entrepreneurship Finance: A Global Perspective. In Creating Entrepreneurial Space: Talking through Multi-Voices, Reflections on Emerging Debates Contemporary Issues in Entrepreneurship Research; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Shrotriya, D.V. Internal Sources of Finance for Business Organizations. Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 2019, 6, 933–940. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.; Oparaocha, G.O. Crowdfunding: Motives, Definitions, Typology and Ethical Challenges. Entrep. Res. J. 2017, 7, 20150045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavitis, C.; Filatotchev, I.; Kamuriwo, D.S.; Vanacker, T. Entrepreneurial Finance: New Frontiers of Research and Practice. Ventur. Cap. 2017, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, S.; Capizzi, V.; Cumming, D. Emerging Trends in Entrepreneurial Finance. Ventur. Cap. 2019, 21, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimurzina, B.; Kamenova, M.; Omarova, A.; Bodaubayeva, G.; Dzhunusova, A.; Kabdullina, G. Major Sources of Financing Investment Projects. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 7, 1555–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashourizadeh, S.; Saeedikiya, M.; Aeeni, Z.; Temiz, S. Formal Sources of Finance Boost Innovation: Do Immigrants Benefit as Much as Natives? Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2022, 10, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Demirguckunt, A.; Maksimovic, V. Financing Patterns around the World: Are Small Firms Different? J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 89, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D.; Johan, S. The Problems with and Promise of Entrepreneurial Finance. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2017, 11, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghenea, M. Ghenea-Marius-Antreprenoriat-Cut.Pdf—PDFCOFFEE.COM. Available online: https://pdfcoffee.com/ghenea-marius-antreprenoriat-cutpdf-pdf-free.html (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Chen, J.K.C.; Sriphon, T. Authentic Leadership, Trust, and Social Exchange Relationships under the Influence of Leader Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisdiono, P.; Said, J.; Yusoff, H.; Hermawan, A.A. Examining Leadership Capabilities, Risk Management Practices, and Organizational Resilience: The Case of State-Owned Enterprises in Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hor, S.C.; Chang, A.; Torres de Oliveira, R.; Davidsson, P. From the Theories of Financial Resource Acquisition to a Theory for Acquiring Financial Resources—How Should Digital Ventures Raise Equity Capital beyond Seed Funding. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2021, 16, e00278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, X.; Li, B.; Li, M. Entrepreneurial Management Equity Allocation and Financing Structure Optimization of Technology-Based Entrepreneurial Firm. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2018, 9, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, L.N.; Tuan, K.C.; Duc, N.N.; Thi, U.N. The Impact of Absorption Capability, Innovation Capability, and Branding Capability on Firm Performance—An Empirical Study on Vietnamese Retail Firms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, N.; Xie, R.; Zhang, J. The Impact of Personal Values and Attitude toward Sustainable Entrepreneurship on Entrepreneurial Intention to Enhance Sustainable Development: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerzoni, M.; Taylor Aldridge, T.; Audretsch, D.B.; Desai, S. A New Industry Creation and Originality: Insight from the Funding Sources of University Patents. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Maltitz, A.; Van der Lingen, E. Business Model Framework for Education Technology Entrepreneurs in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Entrep. Small Bus. Manag. 2022, 14, a472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Faoite, D.; Henry, C.; Johnston, K.; Van der Sijde, P. Education and Training for Entrepreneurs: A Consideration of Initiatives in Ireland and The Netherlands. Educ. Train. 2003, 45, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burov, V.Y.; Khokhlova, G.I.; Kretova, N.V. Development of Small and Medium-Sized Businesses in the Construction Industry through the Use of Business Networks. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 751, 012136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtch, T.A.; Au, K.Y.; Chiang, F.F.T.; Hofman, P.S. How Perceived Risk and Return Interacts with Familism to Influence Individuals’ Investment Strategies: The Case of Capital Seeking and Capital Providing Behavior in New Venture Financing. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 471–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettel, M. Business Angels in Germany: A Research Note. Ventur. Cap. 2003, 5, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dina, V.; Gomezel, A.S. What Do We Know about Business Angels’ Decision Making Research Development? A Document Co-Citation Analysis. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2022, 24, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Landström, H.; Mason, C. Handbook of Research on Business Angels; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-78347-172-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, V.; Certhoux, G. Acting as a Business Angel to Become a Better Entrepreneur: A Learning Innovation. Entrep. Educ. Pedagog. 2022, 251512742110702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.M. The Real Venture Capitalists: A Review of Research on Business Angels; Hunter Center for Entrepreneurship: 2008. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/16857926/The_real_venture_capitalists_a_review_of_research_on_business_angels (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Pierrakis, Y.; Owen, R. Startup Ventures and Equity Finance: How Do Business Accelerators and Business Angels’ Assess the Human Capital of Socio-Environmental Mission Led Entrepreneurs? Innovation 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, D. Business Angels and Value Added: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? Ventur. Cap. 2008, 10, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadani, V. Business Angels: Who They Really Are. Strateg. Change 2009, 18, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.A.; Dumay, J. Business Angels: A Research Review and New Agenda. Ventur. Cap. 2017, 19, 183–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Business Angels. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/access-finance/policy-areas/business-angels_en (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Tenca, F.; Croce, A.; Ughetto, E. Business Angels Research In Entrepreneurial Finance: A Literature Review And A Research Agenda. J. Econ. Surv. 2018, 32, 1384–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamna, D.F.; Ilkhanizadeh, S. Can High-Performance Work Practices Influence Employee Career Competencies? There Is a Need for Better Employee Outcomes in the Banking Industry. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinguh, E.; Zoltan, Z. Financial Institution Type and Firm-Related Attributes as Determinants of Loan Amounts. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cehaji, A.; Kosak, M. Macroprudential Measures and Developments in Bank Funding Costs. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 78, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Fang, X.; Tian, Z.; Luo, W. The Impact of Environmental Uncertainty on Corporate Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilker, H.D. Hedge Fund Family Ties. J. Bank Financ. 2022, 134, 106326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. What Makes the Divergence between Cross-Border VCs and Domestic VCs Persist? In the Context of the Chinese VC Industry. Seoul J. Bus. 2018, 24, 15–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantenbein, P.; Kind, A.; Volonté, C. Individualism and Venture Capital: A Cross-Country Study. Manag. Int. Rev. 2019, 59, 741–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.; Jones, P.; Liargovas, P.; Apostolopoulos, N. Entrepreneurship and the European Union Policies after 60 Years of Common European Vision: Regional and Spatial Perspectives. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2020, 32, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvouletý, O.; Srhoj, S.; Pantea, S. Public SME Grants and Firm Performance in European Union: A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 57, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniewski, M.W.; Szopiński, T.; Awruk, K. Setting up a Business and Funding Sources. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2108–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundale, K. Raising Venture Capital Finance in Europe: A Practical Guide for Business Owners, Entrepreneurs and Investors; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ceptureanu, S.I.; Ceptureanu, E.G. Challenges and Barriers of European Young Entrepreneurs. Manag. Res. Pract. 2015, 7, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, G.C. A Policy Response to Regional Disparities in the Supply of Risk Capital to New Technology-Based Firms in the European Union: The European Seed Capital Fund Scheme. Reg. Stud. 1998, 32, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, C.; Foris, T. Training Future Entrepreneurs Using European Funds. A Descriptive Research on Start-Up Romania Programs. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2016, 16, 372–377. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, V.D.; Roman, A. Assessing the Role of Access to Finance for Young Potential Entrepreneurs: The Case of Romania. KnE Soc. Sci. 2020, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanian Government FEMEIA ANTREPRENOR Manual de Utilizare Pentru Depunerea Cererii de Finantare. 2022. Available online: https://turism.gov.ro/web/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Manual-Femeia-Antreprenor.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Nguyen, M. The Impact on Corporate Financial Leverage of the Relationship Between Tax Avoidance and Institutional Ownership: A Study of Listed Firms in Vietnam. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2021, 17, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, P.; Shang, Y.; Han, F. The Effects of Environmental Regulation on Investment Efficiency—An Empirical Analysis of Manufacturing Firms in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L. Venture Capital Exits and the Structure of Stock Markets in China. Asian J. Comp. Law 2017, 12, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, W. An Empirical Study on the Relationship between Economy and Finance in Underdeveloped Areas Based on the VAR Model. J. Sens. 2022, 2022, 2224239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Li, P.; Huang, X.; Fan, L. The Dual Mechanism of Social Networks on the Relationship between Internationalization and Firm Performance: Empirical Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudor, G.-A.; Turlea, I.C.; Mitoi, E. Considerations on the Advantages of Using Leasing in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Audit Financ. 2021, 19, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechaev, A. Methods of Lease Payments Calculating in Terms of Innovations Financing. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2021, 17, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauger, F.; Strych, J.-O.; Pfnür, A. Linking Real Estate Data with Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Coworking Spaces, Funding and Founding Activity of Start-Ups. Data Brief 2021, 37, 107185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC Internal and External Sources of Finance-Sources of Finance-Eduqas-GCSE Business Revision-Eduqas-BBC Bitesize. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zj7yy9q/revision/1 (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Startup Café Creditul Furnizor-Principalul Mod de Finanțare Pentru Firme. În Ce Domenii Se Fac Afaceri Pe Banii Clienţilor. Available online: https://www.startupcafe.ro/finantari/finantari-credit-comercial-firme.htm (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Meena, P. The Growth of Suppliers’credits to India, 1960–1969: Analysis of Major Issues. Indian Econ. J. 1982, 29, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Aaronson, D.; Bostic, R.W.; Huck, P.; Townsend, R. Supplier Relationships and Small Business Use of Trade Credit. J. Urban Econ. 2004, 55, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuñat, V.; García-Appendini, E. Trade Credit and Its Role in Entrepreneurial Finance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Danovi, A. Availability of Alternative Financial Resources for SMEs as a Critical Part of the Entrepreneurial Eco-System: Latvia and Italy. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 33, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macht, S.A. Putting “Entrepreneurial Finance Education” on the Map. Educ. Train. 2016, 58, 984–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emenike, B. Impact of Entrepreneurial Finance on Business Start-Ups in Rivers State, Nigeria. Int. J. Adv. Acad. Res. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, T.; Raturi, M.; Srivastava, P. Ethnic Networks and Access to Credit: Evidence from the Manufacturing Sector in Kenya. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2002, 49, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Pamuk, H.; Ramrattan, R.; Uras, B.R. Payment Instruments, Finance and Development. J. Dev. Econ. 2018, 133, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert, N.; Van de Gucht, L.; Van Hulle, C. The Choice between Bank Debt and Trace Credit in Business Start-Ups. Small Bus. Econ. 2007, 29, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wu, D. Entrepreneurial Education and Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention: Does Team Cooperation Matter? J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.J.; Carmo, M.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Cruz, R.; Martins, J.M. Creating Knowledge and Entrepreneurial Capacity for HE Students with Digital Education Methodologies: Differences in the Perceptions of Students and Entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, G.; Ughetto, E.; Landoni, P. Entrepreneurial Intention: An Analysis of the Role of Student-Led Entrepreneurial Organizations. J. Int. Entrep. 2021, 19, 399–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus-Casas, C.; Eliche-Quesada, D.; Aguilar-Peña, J.D.; Jiménez-Castillo, G.; La Rubia, M.D. The Impact of the Entrepreneurship Promotion Programs and the Social Networks on the Sustainability Entrepreneurial Motivation of Engineering Students. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauceanu, A.; Alpenidze, O.; Edu, T.; Zaharia, R. What Determinants Influence Students to Start Their Own Business? Empirical Evidence from United Arab Emirates Universities. Sustainability 2018, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Student Entrepreneurial Society Transilvania University of Brasov (SAS-UTBv) Societatea Antreprenoriala Studențească. Available online: https://www.unitbv.ro/cercetare/transfer-tehnologic-si-antreprenoriat/sas.html (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Barbu, A.; Isaic-Maniu, A. Data Collection in Romanian Market Research: A Comparison between Prices of PAPI, CATI and CAWI. Manag. Mark. 2011, 6, 349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Howitt, D.; Cramer, D.; Popescu, A.; Popa, C. Introducere in SPSS Pentru Psihologie; Polirom: Iași, Romania, 2006; p. 191. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N. Marketing Research, an Applied Orientation, 4th ed.; Pearson Education LTD: Harlow, UK, 2004; pp. 558–582. [Google Scholar]

- Career Journal. Available online: https://revistacariere.ro/inspiratie/actual/a-fost-semnat-pactul-pentru-educatie-antreprenoriala-pentru-urmatorii-4-ani/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Lecuna, A. Understanding Imagination in Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Res. J. 2021, 000010151520210103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuty, E.; Yustian, O.R.; Ratnapuri, C.I. Building Student Entrepreneurship Activities Through the Synergy of the University Entrepreneurship Ecosystem. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 757012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dams, C.; Sarria Allende, V.; Cornejo, M.; Pasquini, R.A.; Robiolo, G. Impact of Accelerators, as Education & Training Programs, on Female Entrepreneurs. Entrep. Res. J. 2022, 12, 329–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J.E.; Tonoyan, V. Research on Gender Stereotyping and Entrepreneurship: Suggestions for Some Paths Worth Pursuing. Entrep. Res. J. 2022, 12, 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, M. Profesionalism și etică în profesia contabilă și de audit. Rev. Audit. Financ. 2008, 1, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, B. FASB Updates Reporting Standard for Supplier Finance Programs—Journal of Accountancy. Available online: https://www.journalofaccountancy.com/news/2022/sep/fasb-updates-reporting-standard-supplier-finance-programs.html (accessed on 24 October 2022).

| Indicator | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New registrations in the area of entrepreneurship | 136,699 | 135,532 | 134,220 | 109,939 | 148,294 | |||||

| Gender distribution of the shareholders of active legal entities (Female/Male) (%) | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M |

| 37.05 | 62.95 | 37.39 | 62.61 | 37.48 | 62.52 | 37.25 | 62.75 | 36.84 | 63.16 | |

| Sources of Entrepreneurial Finance | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Retained earnings/profit |

|

|

| Personal sources |

|

|

| Supplier credits |

|

|

| European funds |

|

|

| Loans (bank credits) |

|

|

| Leasing |

|

|

| Business-angels |

|

|

| Questions | Research Questions (RQ) | |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | You are interested in entrepreneurship? | Interest in entrepreneurship—eliminatory question |

| Q2 | Do you intend to open your own business in the following 5 years? | Interest in entrepreneurship—eliminatory question |

| Q3 | How well do you know the potential sources of financing for your own business? | RQ1, RQ2 |

| Q4 | To what extent do you think you have potential managerial qualities? | RQ1 |

| Q5 | What rating do you give when performing your tasks? | RQ1 |

| Q6 | How solid do you think your financial knowledge is? | RQ1 |

| Q7 | What sources of funding do you know of? | RQ2 |

| Q8 | To what extent do you think funding sources are being used for financing the business (Retained earnings/profit, Personal sources, Supplier credits, European funds, Loans (bank credits), Leasing, and Business-angels)? | RQ2 |

| Q9 | What is the extent to which you think you would be willing to use the company’s equity? | RQ3 |

| Q10 | How well do you know the sources of financing for your own business? | RQ1, RQ2 |

| Q11 | From the profit of the firm, what is the percentage that you are willing to invest (in the first year, in the second year, in the third year)? | RQ3, RQ4 |

| Q12 | What importance do you attach to using relationships with other individuals to finance your business? | RQ4 |

| Q13 | How do you assess knowing the following information: How well are you aware of the advantages of using European funds?How well do you know the disadvantages of using European funds? | RQ3 |

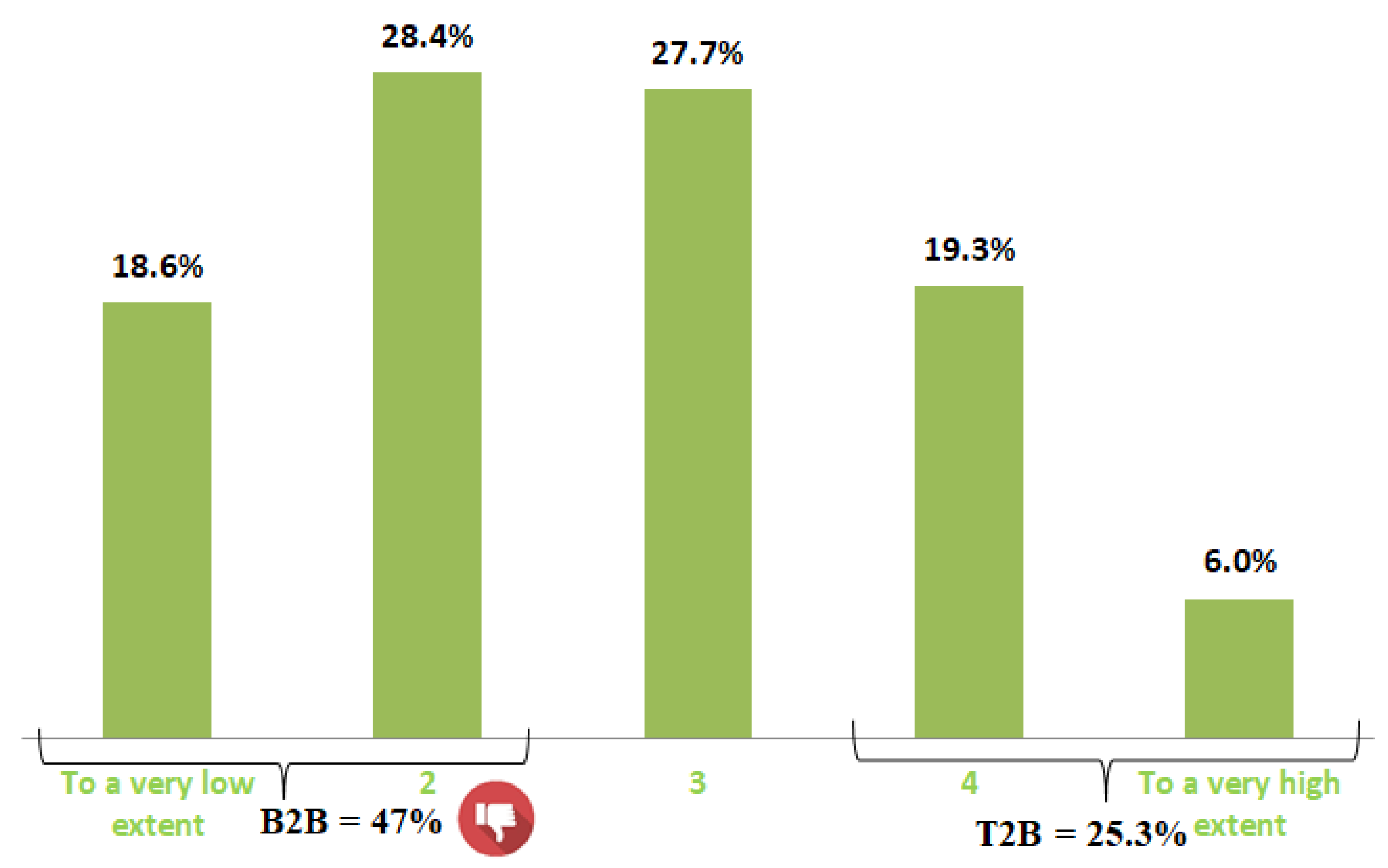

| Q14 | To what extent are you willing to make use of bank loans? | RQ3 |

| Q15 | Indicate your degree of agreement or disagreement with the following statement: Requiring the provision of guarantees for the amount borrowed represents a barrier to accessing the financing source. | RQ4 |

| Q16 | Do you think that the decision on the form of financing also considers the tax aspects (given that the choice of leasing as a form of financing involves VAT, whereas the traditional loan from the bank has no impact on VAT)? | RQ3 |

| Q17 | To what extent would you choose leasing as a possible alternative form of financing (given its greater flexibility than in the case of traditional bank financing)? | RQ3 |

| Q18 | To what extent do you think you would seek the support of a business angel? | RQ3 |

| Q19 | To what extent do you know the market characteristics of your product/service? | RQ4 |

| Q20 | List three factors (the most important ones) that enable business success: | RQ3 |

| Q21 | To what extent are you willing to:

| RQ4 |

| Q22 | To what extent do you think that the information from the courses on entrepreneurial education you attended at the university will help you in opening a business? | RQ1 |

| Q23 | You participated in external entrepreneurial training courses (outside of the courses taken at the university)? | RQ1 |

| Q24 | What is the level of your experience in your current workplace? | Identification questions |

| Q25 | Your gender? | Identification questions |

| Q26 | What is the year of study you are currently in? | Identification questions |

| Sample Structure | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Sample (285 respondents) | Men 26.3% | Women 73.7% | |||||

| Form of education | License degree 90.5% | Master’s degree 6% | Ph.D. 3.5% | |||||

| Current workplace experience | Unemployed 34.0% | <1 year 37.2% | 1 year 17.2% | 2 years 5.6% | 3 years 5.3% | 4 years 0.4% | 5 years and more 0.4% | |

| Retained Earnings/ Profit | Personal Sources | Supplier Credits | European Funds | Loans (Bank Credits) | Leasing | Business Angels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Mean | 3.80 | 3.67 | 3.29 | 3.74 | 3.64 | 3.12 | 2.62 |

| Median | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | |

| Percent (Frequency) | ||||||||

| Categories | 1—Least utilized | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 16.5 |

| 2 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 18.6 | 10.9 | 10.5 | 24.9 | 31.2 | |

| 3 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 36.1 | 24.6 | 22.8 | 33.0 | 31.2 | |

| 4 | 27.0 | 37.2 | 28.4 | 30.2 | 34.7 | 26.3 | 15.4 | |

| 5—Most utilized | 34.7 | 23.9 | 13.3 | 30.9 | 26.0 | 10.5 | 5.6 | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| Value | Df. | Asymp. Sig. (2-Sided) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Chi-Square | 4.212 a | 4 | 0.378 |

| Likelihood Ratio | 4.223 | 4 | 0.377 |

| Linear-by-Linear Association | 2.004 | 1 | 0.157 |

| N of Valid Cases | 285 |

| Value | Df. | Asymp. Sig. (2-Sided) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Chi-Square | 1.370 a | 2 | 0.504 |

| Likelihood Ratio | 1.368 | 2 | 0.505 |

| Linear-by-Linear Association | 0.179 | 1 | 0.672 |

| N of Valid Cases | 285 |

| Retained Earnings/ Profit | Personal Sources | Supplier Credits | European Funds | Loans (Bank Credits) | Leasing | Business-Angels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | Retained earnings/ profit | 1000 | 0.306 | 0.116 | 0.101 | −0.078 | −0.089 | −0.002 |

| Personal sources | 0.306 | 1000 | 0.215 | 0.011 | −0.097 | −0.062 | 0.029 | |

| Supplier credits | 0.116 | 0.215 | 1000 | 0.202 | 0.107 | 0.083 | −0.001 | |

| European Funds | 0.101 | 0.011 | 0.202 | 1000 | 0.106 | 0.029 | 0.204 | |

| Loans (bank credits) | −0.078 | −0.097 | 0.107 | 0.106 | 1000 | 0.334 | −0.006 | |

| Leasing | −0.089 | −0.062 | 0.083 | 0.029 | 0.334 | 1000 | 0.134 | |

| Business angels | −0.002 | 0.029 | −0.001 | 0.204 | −0.006 | 0.134 | 1000 | |

| Component a | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Retained earnings/ profit | 0.650 | −0.267 |

| Personal sources | 0.680 | −0.257 |

| Supplier credits | 0.604 | 0.258 |

| European Funds | 0.459 | 0.379 |

| Loans (bank credits) | −0.034 | 0.717 |

| Leasing | −0.037 | 0.723 |

| Business-angels | 0.210 | 0.330 |

| Component a | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Retained earnings/ profit | 0.696 | −0.100 |

| Personal sources | 0.722 | −0.083 |

| Supplier credits | 0.523 | 0.398 |

| European Funds | 0.352 | 0.480 |

| Loans (bank credits) | −0.208 | 0.687 |

| Leasing | −0.212 | 0.692 |

| Business angels | 0.123 | 0.372 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zamfirache, A.; Suciu, T.; Anton, C.E.; Albu, R.-G.; Ivasciuc, I.-S. The Interest Shown by Potential Young Entrepreneurs in Romania Regarding Feasible Funding Sources, in the Context of a Sustainable Entrepreneurial Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064823

Zamfirache A, Suciu T, Anton CE, Albu R-G, Ivasciuc I-S. The Interest Shown by Potential Young Entrepreneurs in Romania Regarding Feasible Funding Sources, in the Context of a Sustainable Entrepreneurial Education. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064823

Chicago/Turabian StyleZamfirache, Alexandra, Titus Suciu, Carmen Elena Anton, Ruxandra-Gabriela Albu, and Ioana-Simona Ivasciuc. 2023. "The Interest Shown by Potential Young Entrepreneurs in Romania Regarding Feasible Funding Sources, in the Context of a Sustainable Entrepreneurial Education" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064823

APA StyleZamfirache, A., Suciu, T., Anton, C. E., Albu, R.-G., & Ivasciuc, I.-S. (2023). The Interest Shown by Potential Young Entrepreneurs in Romania Regarding Feasible Funding Sources, in the Context of a Sustainable Entrepreneurial Education. Sustainability, 15(6), 4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064823