The Effect of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intention: Mediation of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Moderating Model of Psychological Capital

Abstract

1. Introduction

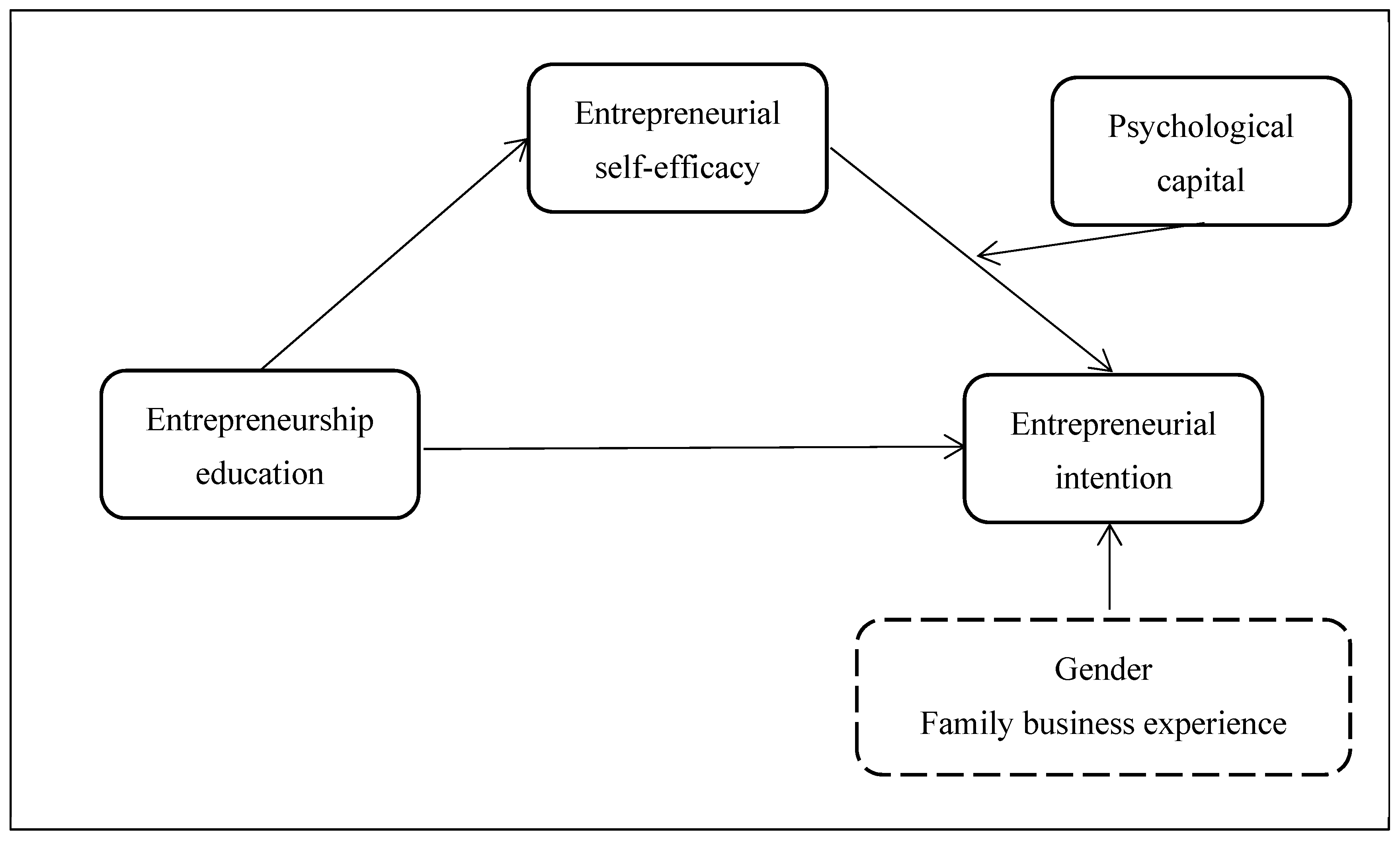

2. Theory and Research Hypothesis

2.1. The Relationship between EE and EI

2.2. The Relationship between EE, ESE, and EI

2.3. The Moderating Role of Psycap

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Data Preparation

3.4.1. Item Analysis

3.4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

3.5. Common Method Variance (CMV) Test

3.6. Difference Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Normality Test

4.2. External Model Evaluation

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

4.3.1. Model Fit Analysis

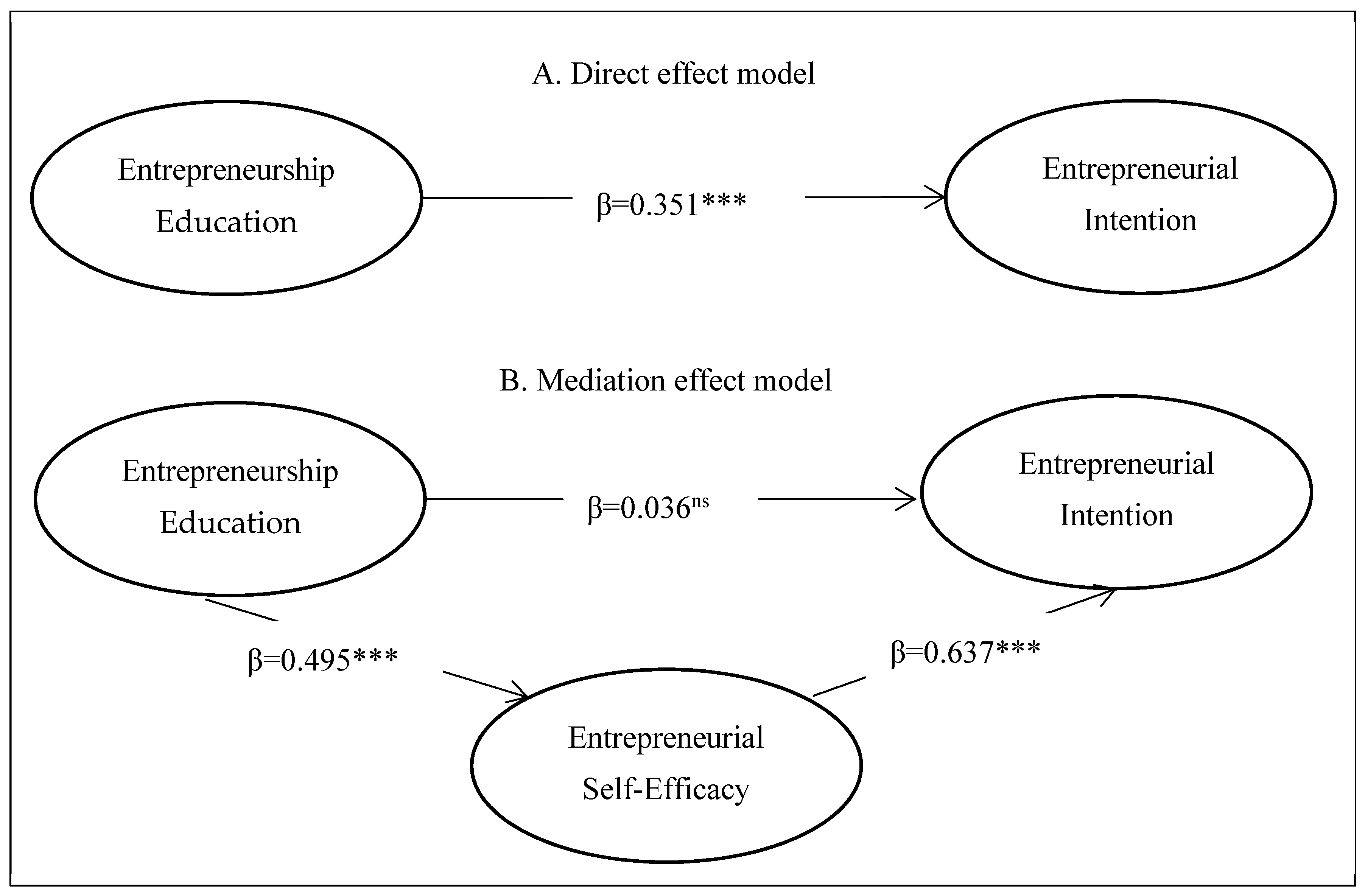

4.3.2. Analysis of Direct and Indirect Effects

4.3.3. Modulating Effect

5. Discussion

5.1. Gender Differences in EI

5.2. Differences in College Students’ EI in Terms of Family Business Experience

5.3. EE and EI

5.4. Discussion on the Mediating Role of ESE

5.5. Discussion on the Moderating Role of Psychological Capital

6. Conclusions

7. Research Limitations and Future Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gieure, C.; del Mar Benavides-Espinosa, M.; Roig-Dobón, S. The entrepreneurial process: The link between intentions and behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tleuberdinova, A.; Shayekina, Z.; Salauatova, D.; Pratt, S. Macro-economic Factors Influencing Tourism Entrepreneurship: The Case of Kazakhstan. J. Entrep. 2021, 30, 179–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V.; Mitre-Aranda, M.; del Brío-González, J. The entrepreneurial intention of university students: An environmental perspective. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 28, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, T.; Heidler, P.; Amoozegar, A.; Anees, R. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Passion on the Entrepreneurial Intention; Moderating Impact of Perception of University Support. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, G.; Kha, K.L. Investigating the relationship between educational support and entrepreneurial intention in Vietnam: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Irfan, Z. Entrepreneurship education: A review of challenges, characteristics and opportunities. Entrep. Educ. 2019, 2, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sha, Y.; Wang, J.; An, L.; Chen, T.; Huang, X.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L. How Entrepreneurship Education at Universities Influences Entrepreneurial Intention: Mediating Effect Based on Entrepreneurial Competence. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.H.; Tang, F.F.; Wu, K.M. An Analysis of the Interaction between Human Capital and Social Capital in the Process of College Students’ Job Hunting. J. Educ. Sci. Hunan Norm. Univ. 2021, 20, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Yang, J. Influence of Entrepreneurial Role Models on Entrepreneurial Intention of College Students: Moderating Effects of Proactive Personality. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2022, 35, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.H.; Wang, J.H. Analysisof the Influencing Factors and Mechanism of Dynamic Changes of College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Educ. Sci. Hunan Norm. Univ. 2022, 21, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Elnadi, M.; Gheith, M.H. Entrepreneurial ecosystem, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention in higher education: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A.; Hmieleski, K.M. Essentials of Entrepreneurship Second Edition: Changing the World, One Idea at a Time; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Akinwale, Y.O.; Ababtain, A.K.; Alaraifi, A.A. Structural equation model analysis of factors influencing entrepreneurial interest among university students in Saudi Arabia. J. Entrep. Educ. 2019, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, S.C.; Liguori, E.W. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions: Outcome expectations as mediator and subjective norms as moderator. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 26, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, I.; Butler, J.C.; Smith, R.M.; Cao, X. From entrepreneurial passion to entrepreneurial intentions: The role of entrepreneurial passion, innovativeness, and curiosity in driving entrepreneurial intentions. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 157, 109758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alferaih, A. Starting a New Business? Assessing University Students’ Intentions towards Digital Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.K.; Burmeister-Lamp, K.; Simmons, S.A.; Foo, M.-D.; Hong, M.C.; Pipes, J.D. “I know I can, but I don’t fit”: Perceived fit, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B.N. From entrepreneurial intentions to behavior: The role of anticipated regret and proactive personality. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gelderen, M.; Kautonen, T.; Wincent, J.; Biniari, M. Implementation intentions in the entrepreneurial process: Concept, empirical findings, and research agenda. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 51, 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Ali, M.; Badghish, S. Symmetric and asymmetric modeling of entrepreneurial ecosystem in developing entrepreneurial intentions among female university students in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2019, 11, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, P.I.R.; Pérez, M.D.P.P.; Galicia, P.E.A. University entrepreneurship: How to trigger entrepreneurial intent of undergraduate students. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2019, 10, 927–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paray, Z.A.; Kumar, S. Does entrepreneurship education influence entrepreneurial intention among students in HEI’s? The role of age, gender and degree background. J. Int. Educ. Bus. 2020, 13, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, G.; Le, T.T.T.; Tran, A.K.T.; Du, T. Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Vietnam: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning orientation. Educ. Train. 2020, 63, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.D. Exploring the link between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: The moderating role of educational fields. Educ. Train. 2021, 64, 869–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wu, D. Entrepreneurial education and students’ entrepreneurial intention: Does team cooperation matter? J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otache, I.; Umar, K.; Audu, Y.; Onalo, U. The effects of entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: A longitudinal approach. Educ. Train. 2019, 63, 967–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbeek, H.; van Praag, M.; Ijsselstein, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2010, 54, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwu, C.G.; Opute, P.A.; Nchu, R.; Eresia-Eke, C.; Tengeh, R.K.; Jaiyeoba, O.; Aliyu, O.A. Entrepreneurship education, curriculum and lecturer-competency as antecedents of student entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, T.; Alvarez, C. Influence of university-related factors on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2019, 11, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval-Couetil, N. Assessing the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education Programs: Challenges and Approaches. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Attitudes and Intention: Hysteresis and Persistence. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F. Intention-based models of entrepreneurship education. Piccolla Impresa/Small Bus. 2004, 3, 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Passoni, D.; Glavam, R.B. Entrepreneurial intention and the effects of entrepreneurial education: Differences among management, engineering, and accounting students. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2018, 10, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.A.C.; Forte, R.P. Prior education and entrepreneurial intentions: The differential impact of a wide range of fields of study. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2017, 11, 353–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunfam, V.F.; Asitik, A.J.; Afrifa-Yamoah, E. Personality, entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention among Ghanaian students. Entrep. Educ. Pedagog. 2021, 5, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, S.; Reyad, S.; Khamis, R.; Hamdan, A.; Alsartawi, A.M. Business education and entrepreneurial skills: Evidence from Arab universities. J. Educ. Bus. 2019, 94, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pérez, V.; Montes-Merino, A.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; Galicia, P.E.A. Emotional competencies and cognitive antecedents in shaping student’s entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of entrepreneurship education. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampene, A.K.; Li, C.; Khan, A.; Agyeman, F.O.; Opoku, R.K. Yes! I want to be an entrepreneur: A study on university students’ entrepreneurship intentions through the theory of planned behavior. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutzler, J.; Andonova, V.; Diaz-Serrano, L. How context shapes entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a driver of entrepreneurial intentions: A multilevel approach. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 880–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, F.; Karadağ, H.; Tuncer, B. Big five personality traits, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1188–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B.N. Entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial intention: The role of social support and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alammari, K.; Newbery, R.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Beaumont, E. Post-materialistic values and entrepreneurial intention—The case of Saudi Arabia. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2019, 26, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, G.E.R.; Rodriguez, J.F.R.; Plaza, A.V.; Zapata, C.P.V.; Zuluaga, M.E.G. Entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Colombia: Exploration based on the theory of planned behavior. J. Educ. Bus. 2022, 97, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeh, J.K.; Bondzi-Simpson, A.; Baah, N.G. Predicting Students’ Response to Entrepreneurship in Hospitality and Tourism Education: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, R.K. Measuring the impact of business management Student’s attitude towards entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: A case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, T.; Farrukh, M.; Heidler, P.; Tautiva, J.A.D. Entrepreneurial Intention: Creativity, Entrepreneurship, and University Support. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.-J. Psychological Capital and Entrepreneurship Sustainability. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluku, M.M.; Onderi, P.; Otto, K. Predicting self-employment intentions and entry in Germany and East Africa: An investigation of the impact of mentoring, entrepreneurial attitudes, and psychological capital. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2021, 33, 289–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrialgo, M.; Iglesias, V. The moderating role of entrepreneurship education on the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 1209–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Barreto, K.; Honores-Marin, G.; Gutiérrez-Zepeda, P.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, J. Prior Exposure and Educational Environment towards Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2017, 12, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafabadi, M.O.; Zamani, M.; Mirdamadi, M. Designing a model for entrepreneurial intentions of agricultural students. J. Educ. Bus. 2016, 91, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, B.A. Entrepreneurship Education’s Impact on Entrepreneurial Intention Using the Theory of Planned Behavior: Evidence from Chinese Vocational College Students. Entrep. Educ. Pedagog. 2021, 4, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, M.P.L.; Martín-Navarro, A.; Ramos-Rodríguez, A.R. Will they end up doing what they like? The moderating role of the attitude towards entrepreneurship in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawan, U.M.; Envuladu, E.A.; Mohammad, M.A.; Wali, N.Y.; Mahmoud, H.M. Perceptions and attitude towards entrepreneurship education programme, and employment ambitions of fifinal year undergraduate students in kano, northern Nigeria. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 3, 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, G.; Battaglia, D.; Landoni, P.; Paolucci, E. Academic spinoffs: The role of entrepreneurship education. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 369–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, S.; Block, J.H. Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, T.; Alvarez, C.; Martins, I.; Perez, J.P.; Románn-Calderón, J.P. Students’ perception of learning from entrepreneurship education programs and entrepreneurial intention in Latin America. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2021, 34, 419–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykolenko, O.; Ippolitova, I.; Doroshenko, H.; Strapchuk, S. The impact of entrepreneurship education and cultural context on entrepreneurial intentions of Ukrainian students: The mediating role of attitudes and perceived control. High. Educ. Ski. Work. Learn. 2021, 12, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Verma, R.K. Engine of entrepreneurial intentions: Revisiting personality traits with entrepreneurial education. Benchmarking Int. J. 2021, 29, 2019–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Lančarič, D.; Egerová, D.; Czeglédi, C. The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1977-25733-001 (accessed on 30 May 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otache, I. Entrepreneurship education and undergraduate students’ self- and paid-employment intentions. Educ. Train. 2019, 61, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, U.; Ali, S.A.; Ahmed, M.; Usman, B.; Sameer, I. From entrepreneurial education to entrepreneurial intention: A sequential mediation of self-efficacy and entrepreneurial attitude. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2021, 13, 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, I.; Saleem, I.; Islam, K.B.; Thoudam, P.; Khan, R. Entrepreneurial intention among female university students: Examining the moderating role of entrepreneurial education. J. Int. Bus. Entrep. Dev. 2020, 12, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomy, S.; Pardede, E. An entrepreneurial intention model focussing on higher education. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1423–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, I.; Thoudam, P.; Saleem, I. Role of entrepreneurial education in shaping entrepreneurial intention among university students: Testing the hypotheses using mediation and moderation approach. J. Educ. Bus. 2021, 97, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souitaris, V.; Zerbinati, S.; Al-Laham, A. Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Hulsink, W. Putting Entrepreneurship Education Where the Intention to Act Lies: An Investigation into the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Behavior. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2015, 14, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Ali, F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital and Beyond; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Avey, J.B.; Luthans, F.; Jensen, S.M. Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfud, T.; Triyono, M.B.; Sudira, P.; Mulyani, Y. The influence of social capital and entrepreneurial attitude orientation on entrepreneurial intentions: The mediating role of psychological capital. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2020, 26, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardana, L.W.; Narmaditya, B.S.; Wibowo, A.; Mahendra, A.M.; Wibowo, N.A.; Harwida, G.; Rohman, A.N. The impact of entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial mindset: The mediating role of attitude and self-efficacy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, D.; Wiklund, J.; Cotton, R. Success, Failure, and Entrepreneurial Reentry: An Experimental Assessment of the Veracity of Self–Efficacy and Prospect Theory. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, A.; Renko, M.; Myatt, T. Danger Zone Entrepreneurs: The Importance of Resilience and Self–Efficacy for Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbu, A.; Zuberbühler, M.J.P.; Salanova, M. Positive Psychology Micro-Coaching Intervention: Effects on Psychological Capital and Goal-Related Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 566293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.K.; Kao, Y.T.; Lin, C.C. Common method variance in management research: Its nature, effects, detection, and remedies. J. Manag. 2006, 23, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.H. Research on the Relationship between College Students’ Entrepreneurial Environment, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Intention. Master’s Dissertation, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M. On the Relationship between Enterpreneurial Self-Efficay Devisionand Enterprising. J. Shaoyang Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2009, 8, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, S.; Dong, Y.H. Positive Psychological Capital: Measurment and Relationship with Mental Health. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2010, 8, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.-W. Development and Cross–Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-H.; Wang, H.-P.; Lai, W.-Y. Sustainable Career Development for College Students: An Inquiry into SCCT-Based Career Decision-Making. Sustainability 2023, 15, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.A.; Rhemtulla, M. Power Analysis for Parameter Estimation in Structural Equation Modeling: A Discussion and Tutorial. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 4, 2515245920918253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-Fattah, S.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming. J. Appl. Quant. Methods 2010, 5, 365–368. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.G.; Yang, Q. Application of SPSS project analysis in questionnaire design. J. Contin. High. Educ. 2010, 23, 107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.L. Questionnaire Statistical Analysis Practice—SPSS Operation and Application; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, M.W. Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice. J. Black Psychol. 2018, 44, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, S.; Ferreres, A.; Hernández, A.; Tomás, I. The exploratory factor analysis of items: Guided analysis based on empirical data and software. An. Psicol. 2017, 33, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W. Asymptotically distribution-free methods for the analysis of covariance structures. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1984, 37, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A.; Long, J.S. Testing Structural Equation Models; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Belmont, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, G.; Rostami, F.; Nadi, A. Analyzing the Dimensions of the Quality of Life in Hepatitis B Patientsusing Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2015, 7, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, G.; Lau, R.S. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 11, 296–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Y.; Wang, Z.H. Thesis Statistical Analysis Practice: SPSS and AMOS Applications; Wunan Book Publishing Company: Taipei, Taiwan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A.; Saleem, I.; Anwar, I.; Hussain, S.A. Entrepreneurial intention of Indian university students: The role of opportunity recognition and entrepreneurship education. Educ. Train. 2020, 62, 843–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.C.; Lu, G.S. A study on the Influencing Factors of College Graduates’ Entrepreneurial Intention and the Mechanism Involved. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. Soc. Sci. 2022, 42, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Demographic factors, personality and entrepreneurial inclination: A study among Indian university students. Educ. Train. 2017, 59, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C. Demographic factors, family background and prior self-employment on entrepreneurial intention—Vietnamese business students are different: Why? J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2018, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemen-Bekx, M.; Voordeckers, W.; Remery, C.; Schippers, J. Following in parental footsteps? The influence of gender and learning experiences on entrepreneurial intentions. Int. Small Bus. J. 2019, 37, 642–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarling, C.; Jones, P.; Murphy, L. Influence of early exposure to family business experience on developing entrepreneurs. Educ. Train. 2016, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I.A.; Amjed, S.; Jaboob, S. The moderating role of entrepreneurship education in shaping entrepreneurial intentions. J. Econ. Struct. 2020, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperopoulos, P.; Dimov, D. Burst Bubbles or Build Steam? Entrepreneurship Education, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 970–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, S.; Wardana, L.W.; Wibowo, A.; Narmaditya, B.S. Does entrepreneurship education and culture promote students’ entrepreneurial intention? The mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset. Cogent Educ. 2021, 8, 1918849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B. Entrepreneurial alertness, self-efficacy and social entrepreneurship intentions. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2020, 27, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lin, C.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, D. Research on the Effects of Entrepreneurial Education and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy on College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive Psychology: An Introduction; Springer Netherlands: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Asimakopoulos, G.; Hernández, V.; Miguel, J.P. Entrepreneurial Intention of Engineering Students: The Role of Social Norms and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zheng, J.F.; Hou, Y.Q. Impact of Normal Students’ Sense of Vocationon Their Study Engagement:The Mediating Effect of Career ldentity and the Moderating Effect of Psychological Capital. J. Southwest Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2022, 48, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Noh, Y. The effects of psychological capital and risk tolerance on service workers’ internal motivation for firm performance and entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolzen, N. The concept of psychological capital: A comprehensive review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2018, 68, 237–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, H.L.T.; Tran, L.T.; Blackmore, J. Internationalization, Student Engagement, and Global Graduates: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Australian Students’ Experience. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2019, 23, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghia, T.L.H.; Giang, H.T.; Quyen, V.P. At-home international education in Vietnamese universities: Impact on graduates’ employability and career prospects. High. Educ. 2019, 78, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, D.T.; Hung, N.T.; Phuong, N.T.C.; Loan, N.T.T.; Chong, S.-C. Enterprise development from students: The case of universities in Vietnam and the Philippines. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Background Variable | Mean | SD | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 3.289 | 0.978 | 8.478 | 0.000 |

| Female | 2.702 | 0.912 | |||

| Family business experience | Yes | 3.147 | 0.968 | 4.293 | 0.000 |

| No | 2.834 | 0.976 | |||

| Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold | - | - | −2–2 | −2–2 | >0.70 | >0.60 | >0.50 |

| EE | 3.066 | 0.938 | −0.481–0.055 | −0.958–−0.376 | 0.832 | 0.833 | 0.555 |

| ESE | 3.453 | 0.658 | −0.770–−0.105 | −0.412–0.814 | 0.954 | 0.970 | 0.601 |

| EI | 2.953 | 0.985 | −0.749–−0.036 | −0.596–−0.486 | 0.945 | 0.945 | 0.743 |

| Psycap | 3.558 | 0.630 | −0.481–−0.05 | −0.519–0.750 | 0.951 | 0.965 | 0.572 |

| EE | ESE | Psycap | EI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | 0.744 | |||

| ESE | 0.427 *** | 0.775 | ||

| Psycap | 0.362 *** | 0.775 *** | 0.756 | |

| EI | 0.310 *** | 0.607 *** | 0.452 *** | 0.861 |

| Threshold | Overall Sample | Psycap Low Grouping | Psycap High Grouping | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFI | >0.800 | 0.911 | 0.907 | 0.899 |

| AGFI | >0.800 | 0.877 | 0.871 | 0.86 |

| RMR | <0.080 | 0.046 | 0.039 | 0.054 |

| SRMR | <0.080 | 0.040 | 0.050 | 0.052 |

| NFI | >0.800 | 0.937 | 0.91 | 0.915 |

| NNFI | >0.800 | 0.935 | 0.929 | 0.919 |

| CFI | >0.800 | 0.946 | 0.941 | 0.933 |

| RFI | >0.800 | 0.924 | 0.891 | 0.898 |

| IFI | >0.800 | 0.946 | 0.941 | 0.933 |

| PNFI | >0.500 | 0.776 | 0.754 | 0.758 |

| PGFI | >0.500 | 0.660 | 0.657 | 0.652 |

| Path | Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval Bias-Corrected Percentile Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bounds | Upper Bounds | |||

| Indirect effect | EE→ESE→EI | 0.315 *** | 0.251 | 0.388 |

| Direct effect | EE→EI | 0.036 ns | −0.060 | 0.132 |

| Total effect | EE→EI | 0.351 *** | 0.262 | 0.434 |

| Model | χ2 | DF | Δχ2 | ΔDF | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | baseline model | 613.908 | 174 | 4.101 | 1 | 0.043 * |

| Model 2 | interference model | 618.010 | 175 | |||

| Path | High Grouping of Psychological Capital | Low Grouping of Psychological Capital | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates | t | p | Estimates | t | p | |

| ESE→EI | 0.635 *** | 10.237 | 0.000 | 0.494 *** | 6.603 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.-H.; You, X.; Wang, H.-P.; Wang, B.; Lai, W.-Y.; Su, N. The Effect of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intention: Mediation of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Moderating Model of Psychological Capital. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032562

Wang X-H, You X, Wang H-P, Wang B, Lai W-Y, Su N. The Effect of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intention: Mediation of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Moderating Model of Psychological Capital. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032562

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xin-Hai, Xiang You, Hsuan-Po Wang, Bo Wang, Wen-Ya Lai, and Nanguang Su. 2023. "The Effect of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intention: Mediation of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Moderating Model of Psychological Capital" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032562

APA StyleWang, X.-H., You, X., Wang, H.-P., Wang, B., Lai, W.-Y., & Su, N. (2023). The Effect of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intention: Mediation of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Moderating Model of Psychological Capital. Sustainability, 15(3), 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032562