1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, ‘inclusion’, along with ‘diversity’, has come to the forefront in the public debate at almost all levels and across very different contexts, both social and geographical. Infrastructure delivery by the public administration has not been the exception, particularly when the infrastructure to be delivered has an intrinsic high social value, such as housing. Moreover, nowadays public administrations aim to regenerate entire districts within their jurisdictions—cities—where housing is only part of the picture. High urbanization rates, rapid population growth, diminishing public budgets, among many other causes, have made public officials turn to the private sector in the search for financing, but also know-how regarding complex multi-use developments, better value for money designs, and better maintenance and operation practices. This has all paved the way for the rise of public–private partnerships (PPP) over the last four decades. However, over the last two decades, public opposition on one hand, and a public push for participation on the other, has made some consider expanding such partnerships to include—through different ways and methods—people and organizations into the discussion. The work here presented, therefore, aims to be the first literature review on what has become, over the last fifteen years, a concept of its own: public–private–people partnerships (4Ps), the result of widespread demands for more social inclusion, but that still lacks—from our point of view—a clear consensus upon the extent of that inclusion.

The introduction follows a constructivist sequence, where each of the building blocks of our topic of interest—4Ps—is briefly introduced and contextualized. Then, the concept is deconstructed through a thorough analysis and scrutiny of its related literature. Some relevant case studies are also included, in order to shed light upon the many possibilities these kinds of partnerships could offer, but also to highlight possible new research avenues. Hence, the importance of this work lies in its authors’ curiosity about to what degree could the ‘people’ become partners within partnerships, particularly those dealing directly with their living conditions and immediate surroundings.

1.1. Public–Private Partnerships at the Root

Public–private partnerships were conceived as an alternative procurement method for delivering public goods and services through an augmented private participation. The aim has always been to bring the private sector’s expertise, know-how, and resources (financial and other) into the public realm, particularly in times of budgetary deficits and spending cuts [

1,

2]. Countries like the United Kingdom, Canada, Spain, Portugal, and Chile, among others, have, in different periods, embarked on PPP-contracting schemes for updating one or more types of their infrastructure systems [

3]. The UK did so in the 1980s, while Portugal and Spain followed suit during the late 1990s and the 2000s [

4]. Experiences have varied: Portugal, for example, engaged in what was later deemed as an excessive volume of PPP contractual compromises, that led to a fiscal crisis back in 2011 [

5]; Chile on the other hand, had to amend its regulatory framework, based on a troublesome experience of high contract renegotiation rates, which increased costs for the public administration in the long run [

6]. Nonetheless, there are many cases of successful PPP programs. For example, Steijn et al. (2011) found that PPPs in the Netherlands, in general, yield positive outcomes, primarily because of the management strategies employed in the Dutch context [

2]. Morena (2020) also lists at least three major waterfront regeneration projects in Europe—the Copenhagen waterfront, the Paris Plages, and the Bilbao waterfront—successfully carried out by means of PPPs. Such projects, whose budgetary order of magnitude were in the billions of euros, could not have been afforded by public administrations alone [

7].

However, despite the common wisdom that PPPs provide net benefits in most cases, in some others, failures to appropriately address external stakeholders (i.e., citizens and project-neighboring communities), as well as defective managerial practices by public and private actors, have turned many into skeptics, to say the least, with respect to PPP projects over the years [

8,

9]. Failed PPPs, such as the London Underground PPP in 2008, bailed out by the public administration, at a cost estimated to have been between GBP 170 and 410 million of taxpayers’ money, damaged public support for public finance initiatives (PFI) in the United Kingdom, reducing PPP investments in the country to a fraction of the peak levels seen in the early 2000s, over the next decade [

10].

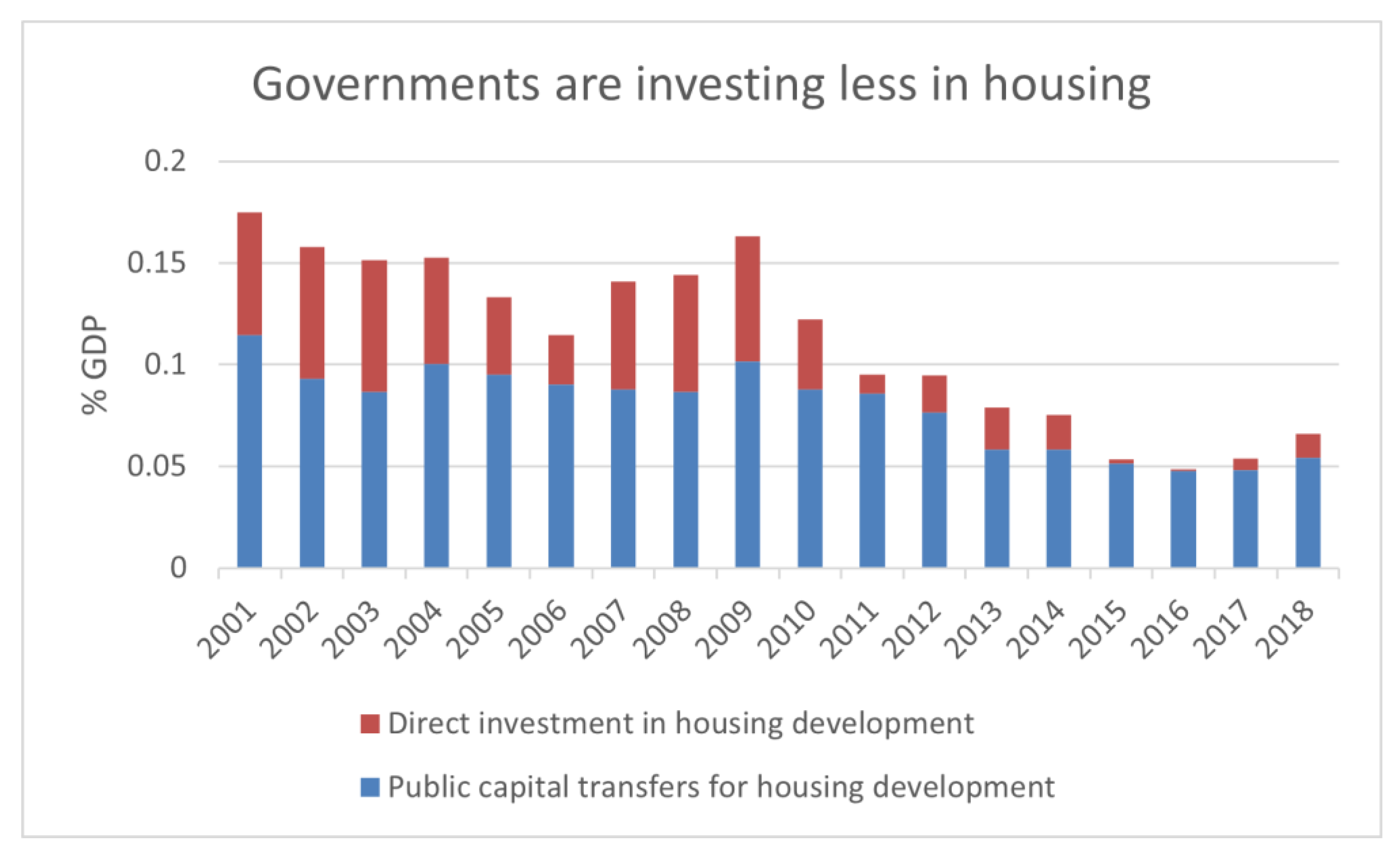

Nonetheless, data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), shows that during the last two decades, in spite of the research available pointing at, (1) ‘citizen engagement’ and ‘community involvement’ as positive factors leading to better performance results [

11], and (2) the refinement and enhancement of PPP frameworks across different countries [

6], the affordable housing market segment could be heading to a critical point on the supply side [

12]. As will be discussed, financialization of the housing market and property-led development appear to be the only driving forces behind urban regeneration and real estate development, which in times of diminishing or even an absence of public intervention via regulatory measures or public investments, is leading to housing supply shortages and processes of gentrification, within many countries and regions [

3,

12].

1.2. Social and Urban PPPs

Upon the perceived benefits of PPPs, governments have widened its application into less pure infrastructure projects, such as highways, to more social in-kind infrastructures [

13]. Social and urban PPPs, particularly those regarding the provision of affordable housing, can be traced back, in the United States, to the Johnson administration, in the late 1960s. As early as 1968, the Housing and Urban Development Act called for an increase in the use of public-private partnerships for the delivery of social housing [

14]. Although this short-lived policy also called for the formation of community development corporations linked to the communities themselves, it was primarily a top-down approach, with mixed results that did not survive beyond the Nixon administration [

14,

15]. More recently, since the middle of the neoliberal heyday of the early 1990s, a public housing demolition and redevelopment program, called HOPE VI, has sought to replace the housing projects with mixed-income communities, by means of mixed-finance partnerships between public, private, and non-profit actors [

3]. This program’s emphasis on the entrepreneurial form of urban regeneration brings us to the broader discussion regarding housing within the context of partnerships: property-led development. The welfare state’s emphasis on affordability and public housing has been superseded by a market-based approach, intended for those who can pay the most [

3]. As a consequence, property-led development has given way to what is often called, ‘housing and neighborhood renewal’, often fostered by public programs such as HOPE VI, and carried out through PPPs. Liberalization of housing markets, through property-led development—along with the shift in values (i.e., from ‘affordability’ to ‘profitability’) it poses, a shift that is often also embodied in public policies—has sometimes led to gentrification processes [

3]. A notorious early example of the financialization of urban redevelopment, as well as some of its potential effects on the city of Chicago, from the late 1980s up to the late 2000s, was described by Weber (2010). By means of what is called “tax increment financing” (TIF), the city of Chicago engaged in the speculative activity of budgeting urban redevelopment works by increasing property taxes a priori on the areas to be worked upon in the future. At the same time, the city’s borrowing levels increased on the basis of TIF’s projected revenues. This eventually led to a real estate bubble burst, subsequent public deficits due to unfulfilled cash inflow projections, and lastly, to tax hikes on property taxes, to be paid by taxpayers and residents [

16]. TIFs have also been employed in other places within the US, such as California and Iowa, with different purposes and mixed outcomes [

17]. Without considering all the positive and negative attributes such a fiscal tool may possess, Pacewicz states that TIFs are, rather than just an innovative financial instrument, a spatial transformation tool [

17].

Meanwhile, in the UK, property-led urban regeneration policies became dominant after Thatcher’s ascension to power in 1979 [

13,

18]. Similar policies have been adopted in countries such as South Africa, the ABC countries (Argentina, Brazil and Chile), China, South Korea, and the former Soviet sphere, with mixed results and questionable effects on communities, according to some scholars [

3,

18,

19]. As an interesting contrast, it is worth discussing the cases of three developing countries in two different time periods: Malaysia, Tanzania, and South Africa. According to Miraftab (2004), a PPP housing policy in South Africa, based on subsidies transfers through developers and credit lines for low-income earners, failed to achieve the goals of affordable housing development during the 1990s and early 2000s. The author states that one of the main causes for such a failure, was a biased policy, designed to benefit banks and private firms, that were more concerned by reducing costs and ensuring their profit margin rather than providing a ‘decent’ residential unit [

18]. Along the same lines, of housing provision through subsidies, Moskalyk (2011) argues that the only reason affordable housing provision through partnerships has been a successful endeavor in the rich Global North, is due to governments’ financial capacity to provide a high level of subsidies, a “luxury” poorer countries from the Global South cannot afford [

20]. As what could be interpreted as a response to both Moskalyk’s and Miraftab’s points of view, Kavishe et al. (2018) take as an example the Malaysian PPP-based housing policy, arguing that the success factor for affordable housing provision is rather the preparation of strategic plans and appropriate policy design beforehand [

21].

However, since the beginning of the current economic scheme skewed towards augmented private participation, scholars have been interested in how, from the opposite direction, citizen and community participation have been promoted within partnerships, even if just symbolically. In addition, there is a recurring debate on what constitutes the ‘public’ within a partnership, a debate that has gained some traction now, in the sunset of the neoliberal consensus.

1.3. Early Community Involvement in PPPs

Unsurprisingly, Britain delivers much of the earlier literature available regarding community involvement and citizen participation within partnerships. While McCarthy et al. (1999) and McCarthy (2007) showcase one of the biggest regeneration initiatives carried out in the United Kingdom from the early 1980s up to the mid-2000s, in Scotland, along with all its transformations, others, like Penn (1993), pointed out the early challenges posed by the dynamics between fragmented public authorities and community organizations, in addressing key regeneration aspects [

22,

23,

24]. On the challenges within communities themselves in the UK, while engaging in partnerships, one of the earliest works found is that of McArthur (1993). The author posed some remarkable questions regarding the extent of the participation, the population scale to which the partnerships would be extended to, and the knowledge that community representatives should acquire in order to be able to effectively partake alongside decision-making officials in the regeneration decision loop [

25].

On the other hand, Hastings (1995) offers some interesting remarks about community participation in the early Scottish urban regeneration partnerships. The author argues that, even though community representatives did not feel that they were fully involved within the partnerships, they felt they had the opportunity to educate the public and private partners more accurately on the problems they faced as a community [

26].

According to Ball (2004), as of 2004, community involvement was a requirement for public-sector funding of urban regeneration initiatives in the UK. Even though property-led development continued to be the main driving force of urban regeneration, the 1990s saw a shift towards augmented community participation within initiatives that were often channeled through PPPs. Interestingly, the author defines ‘community involvement’ as a synthesis of ‘consultation’ and ‘representation’. Along that line, the author states that community empowerment involves taking control of public-subsidized resources. Empowerment is also associated with strong redistributive and decision-making faculties for the benefit of lower income groups. However, it is also recognized in the paper that consultations carry additional costs for projects themselves, impacting the incentives and costs structures [

27].

Given the limited amount of literature available at the time measuring the performance of such cooperation schemes between the community and other partners (local government, local business representatives, and developers), the author conducted a survey on local authorities’ officials and property-sector agents (registered social landlords, property consultants, and property developers), to gain an insight into whether community participation was providing desirable results or not. According to the empirical findings, the overall responses regarding community participation in the governance of urban regeneration partnerships was viewed in a rather negative light by non-community partners. Despite some positive responses, negative ones focused on the unrepresentativeness, a lack of trust, and (lack of) process efficiency, resulting in costly delays. Even though the paper did not advocate the exclusion of communities from urban regeneration initiatives through partnerships, and did not regard the survey results as definitive, it may have cast, back then, issues and concerns that could still be present in today’s urban regeneration initiatives.

Rigling Gallagher et al. (2008) stress the benefits of community involvement in brownfield redevelopment projects in the US, mostly carried out by means of PPPs. The authors analyzed four brownfield sites in different cities across the US, concluding that community and civil society participation often bring benefits for both the private sector and the communities. However, the authors also highlight a particular case in Austin, Texas, in which, after a lengthy process (two years) of consultation between the developers and the tertiary stakeholders, including residents and community members, the project was left on hold because of community demands for affordable housing and concerns over gentrification. This case, according to the authors, also showcases the potential downsides of community involvement in brownfield regeneration initiatives through partnerships [

11].

However, as mentioned before, since the advent of neoliberal policies during the 1980s, in both the US and the UK, and on a global scale during the next decade, when the financialization of real estate became one of the key elements of market-oriented liberalization, scholars started highlighting some definition-related imprecisions with respect to the terminology employed when speaking about PPPs, particularly when defining the ‘public’ partner and their role [

8]. As will be shown below, these imprecisions are still embedded in the more recent public–private–people partnerships.

1.4. Public–Private–People Partnerships

When speaking about housing, be it as part of urban regeneration projects or as affordable housing provision projects, PPPs acquire a whole new dimension, a ‘people’ dimension: involvement through direct participative processes. Over the last two decades, the concept of public–private–people partnerships (PPPP or 4P) has come to the forefront, as a possible way to care for citizens’ concerns over real or perceived threats stemming from large urban redevelopments within or near their communities. Increasing demands for participation in planning and design processes have seen the involvement of organized and proactive citizens, worrying that a project nearby their neighborhoods may lead to displacements, community tissue breakdown, further social and economic inequality, or, simply put, existing residents’ needs not being met or taken into consideration [

19,

28]. In fact, Amaral et al. (2018) offer us some specific socioeconomic factors that, if present in a given context, could predict either the keenness of a public authority to delegate a service provision to a private party, as well as the potential resistance of citizens to such a shift: unemployment rate, taxation levels, income inequality levels, and unionization rate [

29]. These factors are consistent with what was mentioned previously, about citizens’ concerns over redevelopment initiatives near their communities.

However, generally speaking, although the specifics and technicalities of appropriate contract design and financial structuring of a PPP emphasized by some authors are absolutely necessary [

30], nonmonetary determinants (i.e., social factors, political factors, citizens’ sentiments, and end user inclusion) do play a major role in the broader politics of PPPs. As will be illustrated, failing to consider external stakeholders and/or not engaging citizens or end users, at least in an informal way, could determine the success or failure of a PPP, notwithstanding how well its technicalities and contract details were tailored. The point of this paper is thus to deliver—not without questioning or reflecting upon—a comprehensive background and literature review regarding PPPPs, public–private partnerships with the end user as a full-standing stakeholder.

2. Methodology

The ‘search and collect’ process for the literature, regarding the main topic of this article (public–private–people partnerships), was mainly carried out through Scopus, during 2021 and 2022. The main keywords searched on the platform were for ALL fields: ‘public-private-people-partnership’ AND ‘pppp’ (its main acronym). The inquiry was then further refined by limiting the results to social sciences, engineering, business, environmental sciences, decision sciences, economy, and multidisciplinary fields. Other specific keywords were also included, to purposely exclude articles deemed irrelevant with respect to the focus of this article, such as ‘solar’ OR ‘low-carbon’, for energy-related articles, ’smart-city’, for technology and services-related articles, and ‘COVID-19′, for the recentness of the topic.

The main criteria for article inclusion in the literature, was that the content either had a link to the topics of housing, urban regeneration, or social infrastructure, or presented a framework, a methodology on how to establish a public–private–people partnership. Other supporting literature was also included, but only with the purpose of aiding in the definition and contextualization of the main topic’s precursory terminology. For that reason, some articles focused on stakeholder management within partnerships, were considered relevant and therefore included. Likewise, literature already cited in previous works indirectly related with this work’s main focus, was also excluded, in order to avoid repetition and to bring the discussion into new waters.

4. Public–Private Partnerships as a Broad Concept

In order to set a logical starting point for the discussion on what a 4P is, it is important for us to be clear on how the broader concept of a common PPP is defined. For this, Martin (2006) proposes a ‘consensus definition’ on PPPs:

“

Public-private partnerships (P3s) are a class of public contracts for the construction or rehabilitation of public facilities and public infrastructure and for the provision of supportive of ancillary services. P3s generally involve a mix of the following component parts: design, construction, financing, operations and maintenance”. [

53]

Other authors instead, have moved on to describing actual experiences on housing and urban-related PPPs, particularly in the Global South. Ibem (2011) delivered a comprehensive critique of the Nigerian PPP policy related to housing provision as of 2009. According to the author’s work, legal constraints de-incentivizing the engagement of local governments and grassroots organizations in pursuing PPP housing projects, and an absence of uniformity in the PPP policy at the national level, have led to a PPP housing market slightly skewed towards providing housing for middle- and upper-income earners. Interestingly, in this paper’s final recommendations, the author stresses the proposal of providing free land to developers as an incentive for low-income housing development, and empowering low-income citizens financially through a multi-sectoral job creation strategy [

52]. On the other hand, Izar (2019) elaborates on a housing PPP project called Casa Paulista, which exemplifies what was a top-down initiative, carried out by Brazilian authorities, for the provision of housing to low-income earners in central São Paulo. The author describes an alleged planning and tendering process carried out behind the back of the local residents and organized housing groups, a lack of contractual provisions establishing housing affordability beyond the end of the initial mortgage contracts, and a lack of an overflow of benefits towards the project’s surroundings, given the initiative’s narrow focus on property development [

47]. Meanwhile, Kavishe et al. (2018) tackled what they considered a major concern for governments with respect to their duty on providing and/or promoting affordable housing for the disadvantaged, but also for private investors with respect to the feasibility of getting involved in P3s dealing with housing: land ownership. Land property and land acquisition, particularly throughout African, Middle Eastern, and Southeast Asian countries, pose a concern regarding the delivery of social housing by means of PPPs [

21]. The full transfer of public lands to private investors as a risk mitigation tool has been suggested, thus making such a partnership feasible for investors [

21]. The argument for this proposal is reasonable up to a certain point: there is a high demand for housing and an urgency to meet it as soon as possible.

On some further critique of the public sector when procuring social infrastructure through PPPs, Abdul-Aziz et al. (2011) conducted a survey on different public agencies in Malaysia that have engaged in housing PPPs from time to time. Their main findings were, that public agencies engaged in PPPs as a last resort, when a lack of resources, including professionals with the appropriate expertise, made them reach out to the private sector, looking for assistance. In addition, the authors identified several success and failure factors in the public management of PPPs, ranging from taking action against errant developers, as the success factor with greatest impact, and lack of robust and clear agreements as the failure factor with the greatest impact [

54]. On the other hand, Alim et al. (2016) call for the public sector to be more responsible during the pre-construction phases, in particular during the design phase. The authors argue that public officials should have full understanding of all the technical, financial, and regulatory features of the projects before publishing a request for proposals (RFP), allowing them to be in a stronger position for negotiating with the private sector afterwards. Besides, knowing about the perks of a project could protect against the private sector building up price cushions and asking for higher subsidies, while also lowering the overall chances of contract renegotiations that typically end up increasing the costs for the public sector [

55].

In a note related to the interaction between urban planning and public–private (PP) urban development initiatives, Margalit (2013) focuses on what has been the Israeli experience, following decades of spot-zoning in the Tel Aviv–Jaffa area. According to the author, planning flexibility has led to a form of urban PP planning where the public administration has bargained public benefits and lands for financial resources coming from private developments, rebranded as public–private urban revitalization initiatives. PP planning, as an urban development policy, has met with less-than-optimal results, civil resistance, and criticism from professionals and neighboring dwellers, who feel that the public interest has not always been defended by public officials, as supposed [

56].

Thinking on a broader scale, such as cities or districts within them, Morena (2020) goes onto enumerate and describe several waterfront regeneration projects successfully carried out through PPPs in Italy and other European countries. The author also discusses the topic of ‘civic crowdfunding’, as a promising and innovative tool, still yet to be fully exploited, that could help to motivate citizens to engage in the redevelopment of their neighborhoods or other areas of interest nearby, through voluntary financial contributions [

7]. Meanwhile, Fainstein (2009) goes over mega-projects carried out through PPPs in cities like New York, London, and Amsterdam, digging deeper into four urban PPPs to illustrate the different approaches, particularly regarding housing, across the Atlantic. Even though there has been a convergence of American and European policy makers on bringing in private partners for the provision of social infrastructure, the author goes on to trace the historical path of affordable housing delivery, to show the present-day differences in degrees of public benefits resulting from such projects. The key for larger public benefits, the author argues, is the social-democratic ethos still prevailing in Amsterdam and, to a lesser degree, in London, where governments ask more from developers and have a larger role in financing affordable housing developments, as opposed to New York and the US Federal Government since 1974 [

15].

On stakeholder management, and defining the first ‘P’ in a traditional PPP, Henjewele et al. (2013) propose a model on multi-stakeholder management for PPPs, in which the external stakeholders, i.e., the people, are engaged and made part of the project, i.e., de-marginalized. The methodology consists of five different processes to be deployed during the pre-constructive process and beyond: identification/review of stakeholders, profiling and prioritizing of stakeholders, building/managing relationships and knowledge, updating/managing concerns and conflict, and managing communications. According to the author, this methodology comes as a proposed solution to the tense relations and lack of transparency perceived by the public regarding PPPs in Africa, the Americas, Australia, and Europe. People now, and then in 2013, demand a more influential place in the processes, as well as more knowledge regarding procurement and partnerships. If appropriate engagement makes external stakeholders perceive themselves as co-owners of projects, the chances are that the willingness to support PPPs will increase [

42]. On that same line, Rwelamila et al. (2015) present a list of protests called against PPP projects in several countries since the late 1990s, up to a couple of years prior to their study. Again, they bring to the forefront the issue about what constitutes the public in a PPP, and address this question by using a principal-agent model, to analyze how the delegation of faculties from what should be public officials as agents of the general public in a PPP, could end up degenerating the public sector’s involvement in a PPP, i.e., its inherent, albeit partial,

publicness. This degeneration of the ‘public’ leads, according to the authors, to an alienation of the greater public, the citizens, from the PPP project itself. This marginalization has been identified as the main root for citizens’ opposition to PPP projects throughout different countries, but more acutely, in countries of the Global South. The authors call for a solution in the form of appropriate stakeholder management, in particular when dealing with external stakeholders—citizens—and the appropriate definition of what constitutes the first ‘P’ in a PPP, the public, that is, to be the agent of the true principal, the people [

8]. Building upon the publications of Henjewele et al., and Rwelamila et al., Amadi et al. (2018) showcase the experience of handling these same stakeholders in two transportation PPPs in Nigeria. Even though they were not social projects per se, citizens were cared for and listened to, allowing for the identification of key enablers, in order to mitigate opposition against the projects. These enablers were, project location, transparency of internal stakeholders (public and private partners), timing of engagement, general knowledge about PPPs, and the relationship between the internal and the external stakeholders [

9].

More recently, Yang et al. (2020) conducted a stakeholder analysis for a water resources and sewage project in China, carried out through a PPP. The authors defined PPP projects’ stakeholders as individuals or organizations that, being affected by the project’s implementation, also exert influence over it during the whole life cycle. In their analysis, they labeled “the public” as the people, the end users and payers of the project. In that regard, they stress the importance of nurturing the communication with citizens, as public opposition to a project constitutes one of the main risks a PPP could face with regard to its performance [

34].

Although they do not make any reference to PPPs in their article, the conclusions drawn by Bonnafous-Boucher and Porcher (2010), regarding the debate over stakeholder theory—developed largely by Robert Edward Freeman in several works published from the 1980s up to the early 2000s—versus the theory of civil society, could well be used for anchoring, even further, the theoretical foundations of 4Ps. Even though the literature on 4Ps does not make any reference to this debate, we see an interesting intersection between the literature produced by 4P-focused authors and Bonnafous-Boucher and Porcher’s work. Furthermore, public–private–people partnerships could well be a practical manifestation of some of their conclusions:

“

It also suggests that those third parties express themselves in direct relation to the activities of the firm [i.e., big business], with the public authorities playing no more than the role of mediator between private interests”. [

57]

However, the main diverging point with this rationalization and 4Ps’ would be the focus of such third parties’ actions: in stakeholder theory, third parties’ courses of action consist of asserting their interests in front of privates’ (big businesses) interests, while in 4Ps, the interest is mainly public, and the challenge is usually to convince such big businesses to look for opportunities in otherwise purely public affairs [

57]. Along these same lines, Beuve et al. (2018) bring another interesting reflection regarding “opportunistic behavior”, and its possible interference in a PPP agreement [

58]. The authors recognize that such a behavior could come from any party, be it the public sector, the private partner, or even third parties. From the perspective of this work, a third party could well be an ignored community, exerting pressure from a socio-political perspective; it could also be an opposing political organization, looking to exploit social discontent; and it could also be another private entity, looking to profit from a failed partnership. Even though the authors point to more rigid contracts as a way to shield PPPs against opportunistic behavior [

58], would it not be more constructive to deduce when an interference is opportunistic, and when it is a legitimate claim? Moreover, would it not be also more logical to engage and include—there where citizens and/or communities could be regarded as potential obstructionist agents—instead of further alienating and excluding them, via stricter contract language? Could engaging social third parties also be a disincentive for opportunistic behavior from other private-corporate agents?

4.1. Public–Private–People Partnerships—Concepts and Definitions

In the previous section, the main issues common citizens—often regarded as ‘external stakeholders’ by public and private officials alike—perceive and/or experience when facing the prospect of a PPP initiative taking place in their surroundings or having some impact in their everyday life, were discussed, according to the literature found on general PPPs. The literature also shed light on some practices, carried out mostly by the public sector, that often lead to costly results, public outcry, and plain opposition. Thus, recognizing the fact that often PPPs, and in particular, the public sector, have failed in taking into consideration the views, interests, and concerns of the general public, especially when the general public is to be the project’s end user and/or consumer, scholars like Wisa Majamaa have come up with a 4th P, for a public–private–people partnership [

46]. After Majamaa’s doctoral dissertation in 2008, the literature regarding public–private–people partnerships (PPPP or 4P) specifically is still scarce and scattered, with the ‘people’ component lacking a widely accepted definition. For example, Liu et al. (2021) include a literature revision of their own, in a paper titled “Emerging themes of public-private partnerships application in developing smart city projects: a conceptual framework.”, proposing a 4P framework for information and communications technology (ICT) and internet of things (IoT) kinds of initiatives, in which citizen engagement would become institutionalized, in the form of constant feedback [

40].

Another interesting approach is presented by Muñoz et al. (2016), in which they advocate for directly including the people as ‘urban entrepreneurs’ within partnerships. They go on to present a wide range of initiatives, business models stemming from the collaborative economy, as well as cases of citizens taking part in delivering solutions for some of their cities’ issues (e.g., small-scale energy co-generation). They also showcase different instruments for inclusion, such as participatory budgeting and crowdsourcing through various projects, either at the neighborhood level or at the city scale. Muñoz et al. also present some instances in which 4Ps are composed of residents and/or community co-ops as full-standing partners within partnerships [

49].

Kuronen et al. (2010) emphasize that engagement within an appropriate 4P framework ought to be carried out not just during the planning process of a partnership, but also during the rest of the subsequent phases up until the projected end user becomes, indeed, an active end user. Besides, interactions between the ‘people’ component and the other stakeholders, i.e., public and private partners, could be formal (e.g., formal comments during the planning phase) or informal (e.g., a unilateral yet consultative relationship with private partners), thus not regulated by any kind of formal agreement [

48]. Along those lines, Kuronen et al. (2012): “

Including prospective tenants and homeowners in the urban development process in Finland”, considered three completed housing projects in Helsinki, two PPP and one 4P. These projects were to be compared to a 4P model already planned and approved—which included future dwellers during the planning phase. A relevant outcome of the study was the role assigned to the local residents, as property owners and/or members of a community cooperative business within the 4P model [

35].

Other authors, like Ng et al. (2013), build on top of the 4P idea a detailed yet conceptual framework, that looks for citizen participation through all the phases of the lifecycle of any given project. It rests on four main principles: inclusiveness, transparency, interactivity, and continuity, and aims at a pro-active engagement of citizens for the creation of informal and semi-formal relationship networks. The introduction of a third party and, consequently, the relationship networks thus created, could lead to the facilitation of the partnership via that third actor [

39].

Meanwhile, Song et al. (2020) published a paper on public participation in common PPPs. They claim that excessive participation of citizens and outsiders may aggravate the complexity of PPPs, and delay the progress of developing them. Their study comprises the examination of boundary conditions and effective thresholds of public participation influencing the cooperative behaviors of the major stakeholders—the public and the private—through an analysis of the evolution paths and dynamic balances—a mathematical model. Even though this paper does not speak at all about 4Ps, the force-like nature between two defined objects it gives to citizenship within a partnership was found to be relevant. The following quotation could open a door for further research in the dynamics between partners in PPPs and 4Ps:

“

However, allowing the general public to participate in the decision-making process of PPP’s inevitably leads to the reconstruction of the benefit structure and institutional mechanism”. [

50]

One of the possible research avenues this statement could open could be trying to define a new benefit structure within a tripartite partnership, in which citizens and/or communities would be full-standing partners. Besides, could that new benefit structure include broader, intangible benefits, in the form of ESG objectives, from the private sector’s perspective? Yet another research avenue could be regarding ownership. Beyond inclusion into the decision-making loop, could co-ownership become a subject of discussion, in particular where landownership is both, an issue for dwellers and an issue for developers?

Kumaraswamy et al. (2015) portray 4Ps from a resiliency point of view, as well as from perceived weaknesses a projected PPP could harbor due to longer [contractual] time spans, higher uncertainty, and higher risks, hard to predict at the outset. Subsequently, the authors suggest a stronger role for the ‘people’ partners within the 4P, giving the example of a solid-waste management 4P project in Bangladesh, in which the extra ‘P’ included citizens, but also community-based organizations and NGOs. Even though this publication is from 2015, they did recognize in advance Song et al.’s (2020) remark about the complications of including the general public in the decision-making process when:

“

…adding participants to the already complex partnerships in PPP raises concerns about even more complex relationships, conflicts, even disputes, hence inefficiencies in negotiation and decision-making processes”. [

44]

On that regard, they seem to suggest that ‘people’ partners should be included in formal—i.e., contractual—relations from the beginning of the partnership. However, projects such as the one of solid-waste management in Bangladesh do not necessarily involve housing or urban redevelopment, but instead a utility infrastructure management. Thus, having established the differences, should ‘people’ partners be included in formal contractual agreements when speaking of urban and/or housing procurement via partnerships?

Aside from the discussion on establishing formal relationships with added participants, and its intrinsic complexities, the authors brought an interesting comment on cultural particularities inherent to each context, when saying:

“Even the “hard” (formal, contractual nature) side of the public-private sector relationship in a PPP would be influenced by socially embedded relationships, such as trust and commitment, for example, in some “traditionally”/locally expected “grace periods” beyond stipulated deadlines for completing tasks of making payments”.

Although the authors refer to the public and private relationships in a PPP, they suggest differences in the “social way-to-proceed” proper in each particular context.

On the topic of resilience, Maraña et al. (2018) propose yet another 4P framework, but for city resilience-building processes. This framework, consisting of three layers: (1) characteristics of general partnerships, (2) characteristics of city resilience building partnerships, and (3) characteristics of public–private–people partnerships, could be described as a qualitative approach to landing on a successful 4P. However, the paper does not address the details of how the characteristics presented should be adopted during the execution phase. For example, when speaking about ‘participation’, the authors cited literature that recognize the challenge of sustaining motivation and active participation in resilience-oriented activities. They do suggest though a wide set of partnering options, both formal and semi-formal (i.e., contracts, memoranda of understanding, cooperation and/or coordination agreements, etc.), for the constitution of an effective 4P. Nonetheless, in Maraña et al. (2020), the very same authors propose a final and validated 4P framework for city resilience-building processes that is a continuation and conclusion of the 2018 paper. Regarding the challenge posed by citizens’ lack of motivation to participate, the authors did point out in their conclusions that:

“

It is important to bear in mind that the creation of a multi-stakeholder partnerships like 4P’s is always challenging. There are certain barriers that hinder successful implementation. (...) 4P’s also have difficulty engaging the “silent majority” or people that are not used to taking part in participatory processes”. [

41]

Previously, the authors pointed out that during the consultation process, some of the experts commented on “the need to work on identifying possible incentives that foster the involvement of all the stakeholder groups”. However, the authors do not present any concrete solution in that regard, implying that no formal [contractual] relationship with the ‘people’ component was considered during the analysis and discussion with the consulted panel of experts.

From a slightly different area, Boniotti (2021) identifies several prototypes of 4P projects related to cultural heritage conservation initiatives in Italy, where elements from the third sector have already been taking part for more than 20 years (2001—archeological site of Herculaneum). One of the key triggers for the involvement of citizens and/or third sector organizations (e.g., NGOs) in a successful 4P scheme has been the use of civic crowdfunding as a complementary financial tool. Furthermore, the author suggests the integration of the ‘people’ component in a form of a ‘quasi-organization’, with a semi-formal set of relations between stakeholders. Interestingly, the Italian law, since 2017, allows for NGOs to assume, via a service contract, the management of cultural heritage assets [

33].

Letelier et al. published “

Contesting TINA: Community Planning Alternatives for Disaster Reconstruction in Chile” in 2018, a paper that illustrates the importance of developing a 4P model based on ‘people’ as full-standing partners within an urban regeneration partnership project. As pointed out by the authors, right after many disaster events, reconstruction efforts in some places are seen as an opportunity to displace people from their communities and from their place within the city, thus facilitating and/or accelerating gentrification processes. This paper also stresses the importance of dealing appropriately with landless people dwelling in high-risk vulnerable zones, and integrating them in any reconstruction and/or regeneration effort launched by public authorities in alliance with the private sector [

28].

Torvinen et al. (2016) incorporate the 4P narratives from Majamaa (2008) and Ng et al. (2013) into their analysis of end user engagement within the partnership-type of procurement. The authors embrace the informal yet proactive nature of the relationship between partners—public and private—and end users that Ng et al. (2013) propose, but also Majamaa’s scheme on a formal and reactive relationship between end users and the private sector, brokered by the public partner. With these two inputs, the authors propose a model for value co-creation through end user engagement in PPPs [

51].

Finally, Ajibade et al. (2012), Asabia et al. (2009), and Eckhardt (2020) propose adapting the 4P concept and principles to water sanitation, and transport procurement and delivery. Essentially, their aim is to enhance the services by introducing pro-active feedback from citizens as end users, and in the case of Eckhardt (2020) in particular, by integrating information and communication technologies (ICT) as service enhancers [

31,

32,

59].

Table 3 shown below illustrates a timeline of the definitions proposed up to this point.

4.2. Case Studies

Building further on Kuronen et al.’s (2012) paper, “

Including prospective tenants and homeowners in the urban development process in Finland”, the authors also present an interesting case study stemming from the 4P model rolled out in a development in Helsinki. In one section of the project—to be developed as a 4P—a child day-care issue arose. The municipality was not willing to invest in a day-care center, despite a lack of facilities in the area. The solution came from a consultation with future tenants, who turned out to be mainly families with children. Thus, it was determined that some of the residential units to be constructed were going to be used as children’s day-cares, with community cooperatives owning the premises, hence being able to rent them to public or private day-care operators [

35].

Sarkheyli et al. (2018) refer to a case study from a waterfront redevelopment megaproject in the city of Portland, to make the case on the benefits that could be brought into PPPs, the allowance and encouragement of strong and proactive community participation. Even though the authors do not mention the term 4P, they do treat communities and other elements of the civil society as important stakeholders, that could allow for a win-win situation. This net benefit for all parties lies in the fact that potential conflicts, as well as general public concerns and demands regarding the project itself, could be identified beforehand, i.e., during the planning phase. In the Portland case study specifically, a development agreement (DA) was reached between public and private partners, after lengthy negotiations. In the DA, community leaders, residents, and other elements of the civil society were able to include their demands and interests, along with the interests of the private partner. One of the obvious results obtained by these tertiary stakeholders was the inclusion of affordable housing into the project [

45].

At this point, it could be useful to clarify, through an example, what kind of partnerships do not constitute 4Ps, despite the social spirit they bear. Porcher’s work on the ‘Hemisphere Social Impact Fund’ PPP for emergency housing provision—and based on social impact bonds—in France, showcases a very interesting and innovative scheme on what a PPP focused on social housing could look like. However, it could not be considered a 4P, since end users are not considered stakeholders. To consider such a PPP a plural partnership (more than the traditional two partners), instead of a traditional one, just because of the addition of social workers for the provision of services, is not what a 4P is about. Social workers are not end users, but service providers with a contractual relationship with public agencies. End users would be the migrants, asylum-seekers, and homeless subjects that, as noted through the publication, are not in any way considered stakeholders in the partnership agreement [

60].

The Nordregio report by Oliveira e Costa et al. (2018) titled: “Developing Brownfields via Public-Private-People Partnerships—Lessons learned from Baltic Urban Lab” showcases the results of the Baltic Urban Lab’s brownfield redevelopment planning project, between 2016 and 2018. Using a PPPP approach to address a wide range of stakeholders (i.e., local businesses, NGOs, future tenants, community groups, financial institutions, property developers, and public planning agencies) this project took place in four different pilot sites: Inner Harbour, in Norrköping, Sweden; Skoone Bastion area and Telliskivi in Tallinn, Estonia; Mükusalas, in Riga, Latvia; and Itäharju-Kupittaa area, in Turku, Finland. The aim of the project was to bridge public and private partners with citizens and other tertiary stakeholders, in order to develop and test innovative methods of engagement, as well as bottom-up solutions for the redevelopment of brownfield sites. The scope of the study was more intended to be on relationship-building testing between traditional stakeholders with non-traditional stakeholders, rather than building up formal partnerships for the redevelopment of large built environments [

43].

But perhaps the most relevant of the case studies to be presented here comes from Irazábal (2016), in “Public, Private, People Partnerships (PPPPs): Reflections from Latin American Cases”. The author divides the analysis between ‘large urban operations’, and ‘inclusionary housing’, commenting on the activities of each of the partners—public, private, and people—within each of the projects analyzed. Within the first category of large urban operations, the author claims that, for example, in countries such as Brazil and Colombia, where PPP policies have been extensively deployed, private developers are incentivized with tax breaks and flexible zoning regulations, leading to higher profit margins and increases in property values, in exchange for investments in public infrastructure, such as social housing. The policies have shown mixed results, like those seen in the Nova Luz project in São Paulo, Brazil, where a PPPP for the renovation of 45 blocks was ultimately abandoned because of the low profitability it showed after residents’ demands were incorporated into the initiative. On the other hand, the SIMESA partial plan in Medellin, Colombia, integrated the community into a public–private partnership steered by a local steel company, with satisfactory results. As smaller landowners were included in the plan as well, and cultural heritage assets were also made part of the redevelopment concept by request of the community, the project was indeed implemented [

19].

On ‘inclusionary housing’, all three cases are from Chile. Named after the communities where the initiatives took place, these are La Chimba, Los Maitenes, and La Poza. In La Chimba, located in the city of Antofagasta, the plan established that ‘affordable, adequate, and well-located housing’, based on an ‘inclusionary zoning’ regulatory model of subsidized housing, was to be supported by the partnership. This model generated inclusion by incorporating the most vulnerable people into the plan, giving way to a project whose inhabitants are a mix of low-income homebuyers and others. In Los Maitenes, a community located in the city of Talca, many people—most of them renters—lost their homes during the 2010 earthquake. Here, affected residents got organized, teaming up with a local construction company called La Provincia and an NGO called Reconstruye, in order to be able to recover their place in the central areas of the city, where they dwelled prior to the disaster. Finally, in the Community of La Poza in the city of Constitución, another city heavily affected by the 2010 earthquake and tsunami, residents—again—got organized and effectively demanded that the reconstruction plan of their homes—to be carried out through a partnership—take into consideration their desire to remain close to the Maule River, as many of them were fishermen [

19].

6. Conclusions

Up to this point, this work’s main objective, of submitting the concept of ‘public–private–people partnerships’ to thorough scrutiny over how it has been defined and applied, has been duly fulfilled. Its contextualization has also allowed contrasts to be established regarding how that ‘people’ component is perceived: sometimes as end users, sometimes as social entrepreneurs, and in some cases, as unentitled dwellers in vulnerable zones. There follows a final summary and conclusions of what has been previously discussed.

6.1. General Conclusions

Although PPPs do offer opportunities for public and private synergy on infrastructure procurement, either urban or social, they should not be treated as a panacea [

1]. Moreover, for some time, neoliberal policies, including PPPs, have been meeting with civil resistance from segments of society that perceive the private sector to have been pushing itself into spaces traditionally regarded as of public character, as some of the literature here discussed clearly exposes [

3]. That could be the case with urban planning [

56], and affordable housing [

19].

The answer for this public-sponsored private-sector push into the urban decision-making space has not been necessarily a public-sector policy rollback, but the invitation, in some cases, and the allowance in the face of pressuring demands in some others, of citizens’ participation and community involvement. This has led to the creation of another layer of publicness, one associated with direct participation rather than the usual institutional representativeness. On that regard, the concept of public–private partnerships—mostly those related with the urban tissue and its dwellers—has been evolving to include an increasingly direct input from citizens on what has come to be known as public–private–people partnerships (4P).

From the literature, it could be stated that the ‘people’ component within the 4P scheme is still somewhat lacking in form and extent. Furthermore, there is a need to appropriately define different types of PPPPs, depending on what is the project at hand. Cultural and historic asset management or environmental remediation initiatives, imply very different dynamics within relationships between actors, compared to those found within an urban regeneration initiative, where people might be in danger of being relocated, without even having the opportunity to at least state their dissatisfaction in a public hearing.

Beyond the South American and the Portland South Waterfront case studies, where actual large redevelopment projects have taken place through inclusive PPPs, the rest of the PPPPs presented could be regarded as cases of enhanced external-stakeholder management. On the contrary, even allowing for the small size of the children’s day-care example in Helsinki, this approach of incorporating future tenants into the project itself could be considered as a prototype of a possible next step, regarding the evolution of that 4th ‘P’ within partnerships, maybe not only as end users but as economic benefits-shareholding actors. The future of 4Ps could lie in transforming the concept into a transversal economic development tool, as opposed to an extraordinary procurement method, only employed on special occasions, such as post-disaster reconstruction or post-industrial brownfield redevelopment.

Regardless of the general outcomes of the Malaysian experience, carrying out housing PPPs, and how the general public has been included (or not) in their partnership schemes, Abdul-Aziz et al. (2011) describe, in their publication on PPPs from Malaysia, that government often provides lands for free or at a discounted rate, either on a freehold or leasehold basis, for the development of housing projects [

54]. There, where informal settlements exist, or where residents are formal landowners but still could be threatened by a public–private urban redevelopment initiative, there could be an opportunity to take the PPPP scheme a step further. Yet, the volume of PPPs dealing with urban regeneration and/or affordable housing seems to be minimal. The cases presented here mostly represent oddities, when considering the broader picture of perceived housing supply shortages, virtual absence of direct government spending, and diminishing government transfers of capital for urban and housing development purposes within OECD countries, where most of the more mature and sophisticated PPP markets and frameworks are located. Even if some adjustments should be made, in order to define more appropriately the ‘people’ component within a 4P, there is also a gap on how to make the other two partners proactively interested in partnering directly with citizens, particularly those economically and socially vulnerable citizens, that live near or within urban zones prone to real estate revalorization processes.

Private investors, only looking for profits, and procrastinating public officials, particularly in the West, need to understand that when the markets and policies fail to satisfy the demand for a basic need, such as housing, or when some segments of the population start to feel that unchecked markets have turned against them by way of, for example, displacements, fringe actors within the political market start to become more appealing. Not seldom these actors become market disruptors, to say the least. If political allies of markets start to see legitimacy as the commodity they are bound to trade with, they would understand quite quickly that partnering with citizens and communities is the winning way to go.

6.2. Limitations and Recommendations

Academically speaking, this work is limited precisely because the literature available on this particular topic is still scarce. But this limitation also represents a huge opportunity for researchers, policy makers, and investors interested in incorporating ESG factors into their portfolios. There is a lot of planning and engineering yet to be explored, that could yield further literature for further theoretical examinations from the scientific community, potentially generating an iterative process between academic work and actual experience.

Further research is needed on 4Ps from the private-sector perspective, in terms of what level of citizens’ involvement is desirable, and how this level of desirability could be optimized by way of adjustments to incentive structures. Parallel to this, more research is needed on the public side, especially regarding legislation on incentives and land use and ownership. Finally, it would be helpful also, to understand the dynamics between traditional and non-traditional private parties (i.e., corporate sector and grassroots or community organizations) and what factors could be introduced into a public–private–people negotiation that could pave the way for more partner-like relationships between traditionally divergent actors.