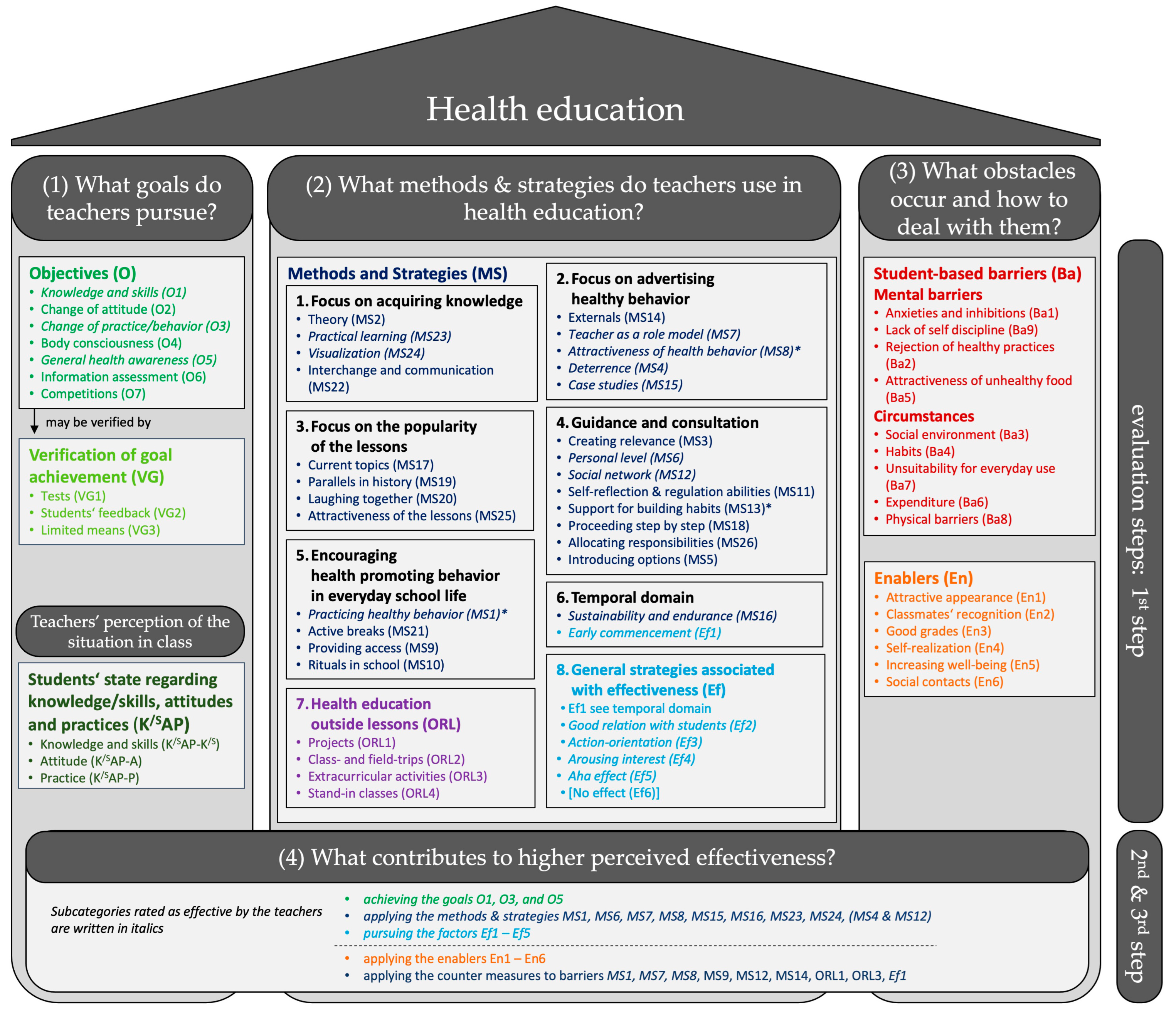

5.2. Results for Research Question 2: What Methods & Strategies Do Teachers Use in Health Education?

The teachers mentioned several methods and strategies (MS) used in their health education classes. These methods and strategies, with specific examples and their perceived effectiveness will be described in the following, with the methods and strategies that share a specific focus being clustered:

Focus on acquiring knowledge,

Focus on advertising healthy behavior,

Focus on the popularity of the lessons,

Guidance and consultation,

Encouraging health-promoting behavior in everyday school life,

Temporal domain,

Health education outside of regular lessons (ORL),

General strategies associated with effectiveness.

5.2.1. Focus on Acquiring Knowledge (MS2, MS23, MS24, MS22)

The method of theory teaching (MS2) was widely mentioned in the interviews. The teachers referred to diseases (T4, 10, 11), nutrition (T1, 6), sex education (T4, 11), and the positive effects of endurance sports (T6). Theory teaching was considered beneficial because it was seen as a prerequisite for performing the activity, e.g., concerning physical activity and nutrition (T1). Additionally, becoming an expert on a particular topic motivated some students (T4), and a theory might enable students to understand the recommendations on healthy behavior (T1, 5, 11). It answered the why question, for example, “Why does it make sense to sit upright?” (T11) and “why are nutrients, respectively carbohydrates, so important?” (T1). Therefore, theory teaching could lead to insights influencing students’ behavior. Moreover, pupils who reject healthy behavior (cf. Ba2) could reflect their point of view through accurate information (T10). However, mentioned disadvantages of this method are, e.g., focusing on specific details could be too theoretical for students (T9). Moreover, pupils’ reading skills have decreased over the years (T9), and T10 observes a tendency for pupils to avoid texts. Consequently, much written information can lead to disinterest (T9, 10).

The strategy of practical learning (MS23) included different methods that required students to perform scientific measurements or experiments to improve their understanding of health. For example, students had to weigh their backpacks, take their pulse, or make a performance diagnostic, e.g., before and after a training plan (T1, 3, 4, 10, 11). The experiments tested ingredients, bacterial growth, or sleep deprivation (T2, 4, 5, 10). To learn more about the food the pupils eat, T2 made yogurt or sauerkraut with them. Furthermore, teachers noticed that students evaluated practical learning as effective, entertaining, and exciting (T2–5, 11). Nevertheless, practical learning relied on a relatively high amount of time and specific equipment.

The teachers also addressed common elements of composing lessons, such as visualization, interchange, and communication. Regarding visualization (MS24), the teachers mentioned various possibilities, e.g., pictures, films, models, or demonstrations. The visualizations may either be created by students (productive) or presented to them (receptive). Examples given included pictures of bacteria (T2), films on food processing (T2), models of contraceptives (T11) or the human spine (T11), which were used so that students could better grasp the given information. In addition, students were challenged to put information into a suitable visualization. Therefore, they had to create a PowerPoint presentation (T4, 8), actively use objects and simulations, e.g., to count the number of sugar cubes in a particular food or drink (T1, 6, 10), or to mimic the experience of being drunk (T3, 11). Teachers evaluated visualizations as important, because they contributed to better comprehension: “If someone tells me, ‘Okay. This bottle contains 300 g of sugar’, then it gets a lot easier to visualize it [the amount] with cubes of sugar.’” (T1 13:20). Additionally, especially films were mentioned as an effective means, as the students are “happy” about it and “actually, a bit [of the information] remains stuck with them” (T11 16:09). However, visualizations like showing movies required the necessary infrastructure (T7). Other common elements of lessons are interchange and communication (MS22). Students are expected to process health-related information, experiences, and perspectives through these measures. For this purpose, teachers implemented discussions in plenum and groups (T2–4, 11). T2 underlined the importance of discussions: “If the children only listen, it’s no use. One [the teacher] really has to allow discussions” (11:58). Further, working in groups or with a partner was common practice in lessons on health education (T2, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11).

5.2.2. Focus on Advertising Healthy Behaviors (MS14, MS7, MS8, MS4, MS15)

Five methods were clustered because of their focus on advertising healthy behavior. Externals (MS14) are considered experts in a particular field, like organizations and institutions informing about drugs (T3, 4), sex education (T11), or cyber mobbing (T4, 11). Also, health insurance companies (T3, 8), sports clubs (T3, 4, 8), doctors (T6), and a physical education college (T10), among others, were named for integrating externals in health education. Sometimes, externals were assumed to be better suited than teachers (T10, 11), e.g., for sexual orientation and identity: “[L]esbian, gay and trans. That is, in fact, a topic at our school. But I think it is really important that this is addressed by externals.” (T11 35:20). Other advantages of externals were that they might be younger, closer to students and consequently talk with them on a different level (T11). Moreover, they are more experienced and better equipped (T10). Schools could offer a broader program by cooperating with organizations like sports clubs. Additionally, accident prevention with experts like firefighters can be highly authentic (T10).

Authenticity also played a significant role in the strategy that teachers act as a role model (MS7). To teach health education persuasively, teachers should model a healthy lifestyle themselves, e.g., healthy eating (T3, 9, 10, 11), cycling to school (T10, 11), and not smoking (T10). The strategy was essential because parents may not act as role models (T3). Moreover, it emphasizes the importance of what teachers have taught (T1, 11). T11 described the effectiveness: “But I think that everything that is set as an example, is always going to be reproduced.” (T11 45:49). However, applying role model behavior creates pressure on teachers as it might interfere with their personal lives. For example: “I smoke a cigarette every now and then, but […] I never do that around students […] because I couldn’t justify that. I mean, why do I smoke as a teacher of biology? And it is important to me that nobody knows that. So that my authenticity stays intact.” (T1 21:11).

Another way to promote healthy behavior is to present it in an attractive way (MS8). Almost all teachers used this strategy, e.g., in the context of nutrition and physical activity. Pupils should experience that healthy food can be delicious (T2, 7, 11). Therefore, teachers prepared healthy food like spinach differently to make it taste better (T5, 7, 9) or made a healthier version of students’ favorite dishes like burgers (T5). This way, the prejudice that healthy food cannot be tasty (cf. Ba2) could be reduced, and attitudes towards certain foods could change. Moreover, nice food is more likely to be imitated at home (T9, 11). In addition, T8 observed that doing trendy sports makes physical activity more attractive.

The teachers discussed deterrence (MS4) controversially in the interviews. Most illustrate the consequences of undesirable behaviors such as alcohol (T3) and nicotine consumption (T5, 8), an unhealthy diet (T3), and driving while using mobile phones (T5, 10). Deterrence was related to visualization (MS24) as pictures or simulations illustrate the consequences (T8). On the one hand, this method is regarded as helpful (T3). Teachers aimed to achieve sensitivity to consequences (T6, 10) and thereby induce changes in practice. T5 explained “that they [the students] themselves do not want to end up like that“ (09:39) and consequently “rethink their own practices“ (09:51). T5 further hoped that deterrence would prove sustainable. In contrast, this method was also criticized. It was seen as “not so nice for a child“ to create fear (T1 17:58). As a result, T7 withdrew from deterrence, and others evaluated it as unsuccessful (T6, 11). T11 explicitly addressed the tendency to believe that one is the exception: “It doesn’t help them when I say ‘you will suffer from gout at the age of fifty’. They don’t know what it is, and one always thinks ‘I won’t get that.’” (T11 41:01).

Case studies (MS15) were another way of highlighting the possible negative consequences of unhealthy behaviors. Teachers either used theoretical cases (T3), invited guests (T8, 11), or encouraged classmates to talk about their experiences with health problems (T4, 8). However, inviting guests involves an organizational effort (T3). Topics mentioned in the case studies were drugs (T3), anorexia (T3), obesity (T11), organ transplants (T11), and accident prevention (T10). Case studies are suitable for discussing triggers for disorders, addictions, and recovery processes (T3, 11). Moreover, case studies promote empathy and reflection as students are impressed by these cases (T3, 5), they provide real-life experiences (T8), and they are associated with good retention (T11).

5.2.3. Focus on the Popularity of Teaching (MS17, MS19, MS20, MS25)

Addressing current topics (MS17) and debates were mentioned by some teachers (T3, 8, 11), e.g., discussions about measles vaccination (T3, 11). This strategy was seen as valuable because pupils are usually interested in current issues and are exposed to different opinions through the media, which may be more or less valid. Therefore, teaching facts about actual topics in school was considered important (T11). T8 described the motivational component: “things that originate not from afar, time-wise, but that are red-hot, and this motivates the most, right?” (T8 26:59). T8 also described the discussions about historical parallels (MS19) motivating students to healthy practices.

Shared laughter (MS20) was another strategy to engage students. For example, T3 explained that the simulation of being drunk (cf. MS23) was “funny“ and that it is essential not to take things too seriously, e.g., concerning sex education. Having fun together was associated with better retention: “And it goes along with big laughter [...]. It is important to have a little bit of fun because, if you think about it, what gets stuck? What do we remember of our school time? It is not a lot, but rather moments, and I try to create such moments.” (T11 15:22).

The last strategy assigned to “focus on the popularity of teaching” is increasing the lessons’ attractiveness (MS25). Teachers indicated students’ preferences and interests as important determinants for their lesson. On the one hand, different options and materials were presented so students could decide what they wanted to work on (T4, 10). Students demand the freedom to address issues that concern them (T4). Next to the topic, students’ preferences relating to methods were also considered. T3 avoided too theoretical approaches “because otherwise, students are bored” (06:14). T11 occasionally formed groups of pupils with homogeneous learning levels. On the other hand, teachers started with a topic and tried to arouse students’ interest through how they prepared the subject. As T11 stated, “it depends on the packaging” (05:07). Teachers could attractively present the topic: “To design an attractive introduction, so that the students really feel like dealing with a carrot. Yes. Well, and that it [the carrot] is maybe more likeable than coming in with a copy in black and white saying: ‘So, that’s a carrot, it contains this and that and that is why it is good.’” (T9 11:41). When pupils liked the lesson, teachers expected collaboration during the class (T4) and better retention (T2, 11). Generally, the enjoyment or fun students felt about a particular method seemed to be an essential criterion (T2, 3, 5).

5.2.4. Guidance and Consultation (MS3, MS6, MS12, MS11, MS13, MS18, MS26, MS5)

The cluster guidance and consultation comprises eight strategies that consider students’ individual situations to incorporate healthy practices into their lifestyles.

The strategy for creating relevance (MS3) followed students’ daily lives and emphasized the impact of their daily behavior on health. Regarding nutrition, teachers focused on foods that pupils like to eat (T3) and are familiar with (T1, 8, 10). In addition, opportunities to purchase healthy foods around the school were discussed (T3). Thus, focusing on students’ perspectives and relevance (T6, 8) was beneficial, as students were able to identify with the content and retain it better (T1, 3–5, 8, 10). Besides, health-promoting behaviors become more realistic and transferable to everyday life (T1, 7). However, a limitation was the curriculum, which limits flexibility (T10). In addition, more concrete materials, such as nutrition plans, would be beneficial in implementing relevance (T7).

The personal level strategy (MS6) referred to teachers’ and students’ experiences and habits. Teachers showed interest in students and their way of life (T3) by acknowledging healthy behaviors and observing their pupils outside of class (T3–5, 7, 11). Students’ experiences and opinions were shared during the course (T2, 3, 7, 8, 11). Sometimes one-on-one conversations were necessary when discussing sensitive topics (T7). Therefore, a good connection with the students was considered a precondition (Ef2). One-on-one talks were also effective in finding ways to change habits because they function as a form of coaching (T4, 7) and in understanding fears that impede the implementation of health-promoting behaviors (T1; Ba1). On the other hand, teachers’ accounts of their experiences and habits were rated as effective in promoting healthy lifestyles (T5, 8, 10, 11; MS7). T10 tried to “become tangible […] [by] sharing personal experiences” (25:29). Also, T10 stated that pupils are interested in their teacher’s lifestyle. Students were “thankful” (T10 26:14) when the teacher saw eye-to-eye with students and emphasized that “what we’re doing here now is important to me, too“ (T10 26:14). The personal-level strategy was seen as effective in changing pupils’ attitudes and mentoring students individually (T3, 7). However, teachers could not realize one-on-one talks with every student (T3). Nevertheless, T4, 5, 7, and 11 pointed out how motivating praise and recognition can be.

According to the personal level (MS6), teachers were also aware of the social network (MS12) to which students belonged. Parents and peers are social influences that seem relevant. Therefore, teachers tried to involve parents in their interventions and used students’ influence with each other. On the one hand, parents received information about health-related topics (T3, 5, 7, 8, 10), e.g., preparing a healthy breakfast for their children (T3). In addition, the parents were asked questions about their families’ habits, e.g., children’s Internet use (T8). On the other hand, teachers worked closely with parents to have a more significant impact on pupils. For example, teachers sought to talk with parents when a student needed further support (T3–5, 7), so that parents were involved in developing solutions. Moreover, parents were informed about the consequences and sanctions when students violate school rules, e.g., unhealthy foods such as chips and energy drinks were banned at some schools (T3). Teachers believed that it was “important“ (T4) and “useful“ (T6) to involve parents. T11 observed parental interest in promoting healthy lifestyles for their children, and T8 generally perceived parental support. T2 highlighted the influence of parents: “the children, first of all, follow the example of their parents“ (05:41). However, parents could also have a negative effect (T11). For example, if the parents are excessively overweight, educating their children about healthy eating may be difficult, and they may not serve as role models for their children (T11). T8 described how parents violate the smoking ban while waiting for their children outside the school and need to be reminded that smoking is not allowed there.

Another critical part of students’ social network were their peers, as students generally crave acceptance (T10). The negative influence older pupils have on younger ones when they engage in unhealthy habits was mentioned only once (T8). In contrast, teachers focused on the positive influence of students implementing health-promoting habits into their lifestyles (T3, 4, 6, 7, 10). They serve as role models (cf. MS7), can support peers, or mentor younger pupils. Teachers believed that advice and criticism are better received when given and modeled by classmates rather than teachers (T4, 7, 8).

Teachers also tried to develop students’ skills for self-reflection and self-regulation (MS11). Mainly, teachers tried to make their pupils aware of their deficits and reflect on their situations and attitudes, for example, by having them track their food for a day to identify their habits (T2). In addition, reflection on one’s relationship with food and body shape in the context of eating disorders was encouraged (T11). Students should also consider other habits, such as managing stress (T7) and consuming energy drinks (T10). Physical education activities could identify deficits in coordination and conditioning (T4, 7, 10, 11). Students could learn what they are capable of and what they are not. T4 explained teachers’ responsibilities: “And thus, many children learn about their deficits, and they should be supported in this case.” (T4 25:26). T10 recommended creating training plans and documenting improvements for fitness deficits, while T4 set specific goals with pupils. For example, apps could help to increase the students’ awareness of how much time they spend on their cell phones, which often encourages them to reduce this time, which is then, in turn, confirmed by the app (T7). T2 performed “silentiums” (quiet periods) to ground the students, and T7 provoked frustration to train mental strength and improve self-discipline (cf. Ba9). T7 explained the general concept of reflection: “The point is to make the student bring up his/her own thoughts, to reflect, to find a way out. [...] To indicate which price I pay for a high media consumption. So. Does that obstruct me in my goals? In the case of education or privately and so on.” (T7 19:44). T7 explicitly contrasted this approach with deterrence (MS4). Nevertheless, T7 is unsure about the amount of time that should be spent on reflection in physical education classes, as less time is available for physical activities.

In order to help students, incorporate healthy practices into their daily lives, teachers tried to support them in building habits (MS13). The interviewer addressed this strategy in each interview to see if and how it was being implemented. T3 and T7 described the idea of this strategy. Pupils should develop automatic healthy practices “not as work, as an obstacle, but like brushing their teeth in the morning, as part of their everyday life“ (T7 27:29). However, T3 was not able to give specific examples of how to build automatisms. T7 suggested always doing some physical exercises before showering. T8 explained that healthy eating habits become natural when students have lunch with a teacher and incorporate healthy eating into lessons or field trips (ORL2). T4 explained that support for building habits is especially relevant for physical education teachers as they strive to maintain an active lifestyle. However, some teachers were critical of the addressed method. For example, building habits is not feasible because it requires consistency (T6) and there may not be enough time (T10). In addition, teachers do not have enough influence on students’ behavior outside of school (T6). T3 raised the question of habit sustainability by comparing the beverages of fifth and eighth graders: Fifth-grade pupils chose water as a beverage, but “the question is, right? Do they maintain that or do they, like the older ones, […] would rather bring their tetra packs of ice tea along” (T3 26:10). T11 believed that students could develop habits in school, but that attitude and intrinsic motivation are crucial to building habits: “I believe one [a teacher] can initiate that and [...] everyone who is up to it, is going to proceed [with the practice], and indeed on their own, independently.” (T11 49:11).

Teachers also used the step-by-step strategy (MS18) or the formation of sub-goals. Rather than expecting each student to achieve an optimal outcome, they wanted their students to acquire at least the most critical information or focus on small improvements. As an example of knowledge about antibiotics, test results showed that many pupils appeared unable to reproduce an explanation for taking the antibiotics for as long as prescribed (T11). Then, it was sufficient that “if they know, keep taking them” (T11 16:56). According to practices, teachers focused on implementation and recognition of improvements (T7), although there was still room for optimization. For example, teachers suggested reducing the consumption of sweets rather than advising their students to avoid them altogether (T5, 9). In this way, they hoped their students would develop balanced eating habits and an awareness of the foods they consume.

During school hours, teachers assigned responsibilities (MS26) to their students. Students were involved in conducting events that enabled their classmates to acquire health-related knowledge or practice healthy behaviors. For example, classes could take turns preparing fruits to sell to their classmates (T3) or a student-run kiosk could help pupils actively apply their knowledge about healthy food (T2). At T4’s school, students were engaged in developing their school’s health program as an extracurricular activity (ORL3). They planned physical activities that can be done in classrooms (cf. MS21). In class, students were sometimes required to present health-related information to their classmates (T7, 10, 11; cf. MS22). Assigning responsibilities was rated useful because it awakens the need for agency and leads to better retention (T10).

Teachers often used the strategy of suggesting different options (MS5) to the students. These options should be applicable and adapted according to the situation, needs, and preferences (T1, 5, 7). T5 recommends straightforward ways to improve the students’ diets: “your brain needs food and energy, and that can be simply a banana” (T5 23:14). Other examples included suggesting alternatives to fast food (T3), riding a bike instead of taking transit (T11), and introducing different ways to increase physical activity that do not require special equipment (T7, 10). T7 explained: “I can show every adolescent a perspective to move, whether in a sports club or casual, like playing Frisbee in a park, that is somehow connected to physical activity” (T7 01:53). However, the effectiveness of suggesting different options was limited as teachers could only provide suggestions; the realization relied on students themselves (T6).

5.2.5. Encouraging Health-Promoting Behavior in Everyday Life (MS1, MS21, MS9, MS10)

All teachers mentioned practicing healthy behavior (MS1) related to nutrition or physical activities. For example, teachers planned a healthy breakfast with students sometimes (T1, 2, 4, 5). Beyond breakfast, healthy meals in general were prepared and consumed (T2, 5, 7, 10, 11). Some teachers even did groceries with their pupils (T1, 11). In addition, teachers also practiced packing and carrying a backpack (T1) and lifting heavy objects correctly on the back (T11). In physical education, endurance sports (T6, 10) and the correct execution of exercises were practiced (T10).

T5 explicitly described this method of practicing healthy behavior as effective. The teachers supported this method for several reasons. First, the experience motivates students (T3, 7, 9) and students could develop an idea of healthy meals in general (T4, 5). Furthermore, pupils may not have the opportunity to prepare meals at home, so it seems necessary to practice this at school (T5). Finally, practicing healthy behaviors allows students to step out of their comfort zone, which is an essential experience for overcoming barriers (T11). In particular, preparing healthy versions of fast food (T5) and trying healthy foods despite initial reluctance (T11) could help overcome the barriers of attraction to unhealthy food (Ba5) and rejection of healthy behaviors (Ba2).

However, restrictions on practicing healthy behavior were mentioned as well. This method cannot be applied to every area of health education. For example, teachers did not consider the practice a suitable tool for sex education, sub-areas of hygiene (e.g., menstruation products), and addiction prevention (T10). Moreover, time is a problem because practicing behaviors requires start-up time and repetition (T1, 3, 5, 7) and the school’s timetable is limited (T2, 10). In addition, teachers only accompany a class for a few years, so regular practice seems complicated (T2). Also, practicing is often limited to sports (T4). Nevertheless, extracurricular activities (ORL3) and events (ORL1/ ORL2) seem to be appropriate opportunities to practice healthy behavior more coherently (T4, 10).

Teachers also encouraged active breaks (MS21) during lessons. Movement is achieved either by interrupting classes to allow activity or by integrating training into the learning process. For example, teachers invited the students to leave the classroom to take a run outside (T1–4), interrupted lessons to do short movement exercises like stretching, or introduced methods to stand up and walk around the classroom (T4, 10, 11). This concept offered “possibilities to get to know things they can do, but also to move while learning” (T4 03:12). This does not require complicated exercises, and even teachers without experience in physical education can easily create opportunities for students to stand up during class (T4). The advantages of active breaks are positive effects on students’ concentration in all-day school (T2, 3, 10) and motivation to be physically active (T3, 4). The strategy of active breaks can be promoted due to the accessibility of the equipment, for example, if each classroom has a box containing materials that can be used for physical activities during lessons (T4).

By providing access (MS9), teachers create opportunities for students to be physically active or eat healthily. According to food, an essential factor is the school’s infrastructure. Kiosks, canteens, or students selling fruits, vegetables, and healthy or healthier foods at comparatively low prices (T3, 4, 8, 11) can lower the spending barrier (Ba6). As T4 pointed out, the foods students eat at school make up a significant portion of their diets, maybe leading to healthier eating. This approach also gives students access to healthy foods they might not yet be familiar with (T1). However, T2 was “skeptical” about the availability of healthy foods and argued that access to healthy foods does not equate to eating healthy foods. Therefore, students might not take the offer and reject healthy food (Ba2). T6 described another problem teachers might face: “There is no healthy food in the conventional sense in our canteen that can be bought. So, what should I do? Advising the students not to eat there?” (16:10).

Another way to incorporate healthy practices into the school day was through rituals (MS10; T1, 3, 8). Examples of rituals included clapping rhythms to improve body control and coordination (T3), eating walnuts in class before or after vacations (T1), and eating lunch together with younger students every day (T8). The effect of rituals is that students know and expect the actions (T1). Rituals are “very important in general“ (T1 25:13) and hopefully students will use these at home. However, introducing and establishing rituals requires time, which is mentioned as an obstacle (T3).

5.2.6. Temporal Domain (MS16, Ef1)

Two factors were included in the temporal domain. One of these referred to the strategy of sustainability and endurance (MS16). Ideally, all teachers should pay attention to children’s habits and food choices during school hours (T3, 8), as it is difficult to drive change individually (T4, 5). In addition, students should be relentlessly challenged and encouraged to maintain a healthy lifestyle (T3, 5). Teachers should not ignore students’ poor eating habits (T3–5) but instead try to talk to pupils. Health education should be ubiquitous in schools, and endurance was generally considered effective (T1, 4). It is necessary to “make more than one attempt to reach students, [because it] doesn’t always work on the first try for everyone“ (T5 03:21). Teachers argued that topics covered in previous courses should be repeated because “constant dripping wears away the stone“ (e.g., T7 29:48). For example, preparing a healthy breakfast once in fifth grade was not enough to make it a habit. Instead, a healthy breakfast should be organized repeatedly (T3). Similarly, interventions that extended over a longer period were helpful and more effective (T7, 10). For physical education, the concept of permanence and repetition seemed applicable because teachers can address health within the context of any sport (T7). Some aspects were considered problematic for the strategy of sustainability and endurance. While the repetition of critical content was effective, teachers also had to ensure that they covered all the different parts and areas of health education (T8). In addition, students should not be annoyed with health-related topics (T8). Finally, projects (ORL1) in the form of project days were critically evaluated because they did not provide continuity (T3).

The effectiveness of starting health education early (Ef1) was noted by two teachers (T1, 5). T5 stressed that it is necessary “to start early in order to have an effect later“ (T5 28:57).

5.2.7. Health Education Outside of Regular Lessons (ORL)

The category contains four clustered methods and strategies referring to health education in schools outside the classroom. Projects (ORL1) are an essential part of the school program and an appropriate opportunity to address health education outside regular classes (T3–8, 11). In addition, projects offer more flexibility in choosing topics. Students can focus on a topic they are interested in or identify with, e.g., the “Impact of computer games on the performance. That were the children who have a PlayStation at home and who might have noticed themselves that they spend too much time in front of it.” (T10 22:14). Another advantage is the more coherent time frame, which may cover when they take place on a day or over consecutive days (T10). For instance, T3 explained that the whole school spends one day working on projects that exclusively address health education. T10 suggested integrating project weeks into the school program and making them compulsory. Nevertheless, as with all methods, a project in itself is no guarantee of success. T6 referred to projects where the program or the responsible person did not meet student expectations or proved to be inefficient (cf. Ef6).

Like projects, class- and field trips (ORL2) were seen as appropriate occasions to provide health education. As teachers explained, health education is either a side benefit or the focus of the trip. For example, regardless of the trip’s theme, food might be organized and discussed with students, which provides an opportunity to address healthy eating (T3, 4, 8). Health education could also be the trip’s focus when physical activities are conducted (T3, 5, 10) or counseling centers for AIDS or addiction are visited (T4, 11). T8 explained the impact: “I do these trips with regard to exercising and health and […] there is attention paid to that. And this is how it becomes natural for them [the students].” (T8 34:52). Nonetheless, class- and field trips are time-consuming, as they require organization and usually take the time that schools would otherwise spend with regular lessons (T11).

Similarly, extracurricular activities (ORL3) were mentioned as a framework in which schools could easily implement health-related activities like physical exercise and preparing dishes (T3, 4; MS1). In some schools, a workgroup deals with health in particular (T3, 4). However, T3 explained that extracurricular activities were integrated into the school day of the younger but not of older students: “We are an all-day school and the structure is like this: students of the fifth class have [...] extracurricular activities [on one day of the week] that are partially physical exercising, there is an acrobatic group, a dance class, a football class, a class for preparing meals, where they pay attention to healthy food choices. Well, that is for class five and that is great [...]. But from the 8th grade onwards, there are lessons in the afternoons [...] and if one would have these workgroup activities for older students in the afternoons that would be really valuable and important.” (T3 21:29). A further occasion to expose pupils to health-related issues are stand-in classes (ORL4), which could be used as an opportunity to address and discuss nutrition with pupils (T6).

5.2.8. General Strategies Associated with Effectiveness (Ef)

Those (sub-)categories referring to effectiveness were either summarized in a special cluster (described here) as far as they were of a general nature, or they were assigned to other clusters of the root category methods and strategies if there was a content-related fit. In

Figure 1 all these effectiveness-related categories are marked with an italic font. In the following, only those subcategories referring to general strategies for enhancing effectiveness are described, because the others were already introduced before (when dealing with the respective clusters they could be assigned to).

The first subcategory of this cluster on general effectiveness is early commencement (Ef1) of health education. Due to the time focus of this subcategory, it was also assigned to another, more specific cluster, which is the “temporal domain” where it was explained in detail. Another subcategory of general effectiveness is having a good relationship with students (Ef2). In the interviews, teachers mentioned the positive influence of this factor several times (T1, 4, 7). A certain level of familiarity between the teacher and the class was seen as essential for thriving health education, as sensitive topics such as physical appearance and intoxicants could be discussed (T4, 7). Action orientation (Ef3) was considered effective too (T4, 5, 10, 11), because it is associated with better topic retention (T11). In addition, experiences can motivate students and help them overcome barriers (T4, 5, 11). Teachers also considered interest (Ef4) and experiencing the aha effect (Ef5) important to making health education more effective. According to T2, interest (Ef4) may arise by teaching theory (MS2) and/or by visualizing content (MS24). Thus, in contrast to regarding pupils’ interest as a precondition, T2 and T11 think that teachers have the power to inspire interest. The experience of an aha effect (Ef5) was deemed effective by four teachers (T1, 3, 4, 5). It may, for example, be generated by surprising insights and experiences (MS2, MS23, MS4; T1, 3, 4) or by overcoming a barrier (Ba5; T5).

However, teachers also mentioned factors, circumstances, or interventions that they considered ineffective (Ef6). Ineffective methods were, for example, lecturing on its own in contrast to allowing questions (T2), exercises based on writing for younger pupils (T6), or reprimanding (T11). T11 and T7 experienced certain pupils who were persistently unable or unwilling to receive health-related knowledge or advice. A limited influence due to their position as teachers in contrast to being parents was perceived as hindering (T6). T6 further referred to interventions and projects that are conducted at their school that appear only to increase the school’s reputation but are not effective (T6).

5.2.9. Second Evaluation Step: Presence of the K/SAP Structure in Health Education

The following part will refer to the K

/SAP structure [

14] as a superordinate pattern to compare and assign our interview data to. This assignment seems reasonable because K

/SAP comprises important outcome variables for health education. The K

/SAP structure is used to classify the learning goals as well as the methods and strategies used by the teachers interviewed.

Teaching objectives, named by the teachers, directly reflect the K/SAP structure (O1-O3) but also go beyond it. The latter becomes apparent in two ways: On the one hand, some learning objectives cannot be clearly assigned to one of these three categories (knowledge/skills—attitudes—practices) but fall in between. Thus, body consciousness (O4), general health awareness (O5), and critical information assessment (O6) contain both knowledge/skills as well as attitude components that are interwoven. On the other hand, participating in school competitions (O7) in the health field has a different focus, concentrating on course development and improving teaching quality in general rather than focusing on personal health development.

Methods and strategies used by the interviewed teachers in health classes were also assigned to the components of the K

/SAP structure. An overview of these assignments, as well as their corresponding justifications, is given in

Table A1. However, many methods and strategies cannot be assigned to just one target category (K, S, A, or P). Instead, they often contribute to more than one category simultaneously (see

Table A1 and

Figure 2).

Looking at the quantitative results of these assignments (thereby taking into account double counting), there is a clear ranking (

Table A1). Most methods and strategies serve the goal of declarative knowledge transmission (K: 19 assignments). A relatively high number of methods also serve to teach procedural knowledge, i.e., skills (S: 17 assignments). The number of methods and strategies referring to attitude formation (including motivational aspects) is somewhat lower (A: 14 assignments), while the lowest number is found for methods and strategies that support the integration of a health-promoting behavior into everyday practice (P: 9 assignments).

Figure 2 visualizes in more detail whether a method or strategy addresses just one target category of the K

/SAP structure or more than one simultaneously. While there are some methods and strategies that separately influence knowledge or attitudes, this looks different for the target category of skills or practices. Thus, skill development is often accompanied by knowledge transfer (the combination of K & S applies to seven methods and strategies). Furthermore, the formation of (long-lasting) practices occurs almost entirely together with the promotion of skills (combination of P & S applies to eight methods and strategies, with two of them also referring to knowledge). It can be noted that attitudes are also frequently addressed together with knowledge transfer (combination of A & K applies to seven methods and strategies).

5.3. Results for Research Question 3: What Obstacles Do Teachers Face and How to Deal with Them?

5.3.1. Barriers (Ba)

Teachers named several barriers that prevent the implementation of healthy practices. Organizational barriers such as time and missing equipment were not the focus of the interview and are therefore not mentioned further here. Instead, we will refer to student-based barriers (Ba). Nine of them were addressed in the interviews, which can be divided into two groups: mental barriers and circumstances.

Figure 3 shows student-related barriers (Ba) in relation to other factors that they affect or by which they have been affected.

Anxieties and inhibitions (Ba1) were mentioned as mental barriers (T1, 4). Students might refrain from asking essential questions in sex education due to embarrassment (T11). If students cannot perform on the same level as their classmates in physical education, a feeling of frustration and inferiority might be evoked (T4). Lastly, body shaming might prevent the pupils from applying necessary hygiene measures, like taking a shower after PE classes (T8). Dealing with these anxieties and inhibitions was regarded as “very strenuous, very laborious, but [...] very important” (T4 27:25). If the teachers were confronted with diagnosed mental illnesses, the situation for them became more complex (T11). T1 and T4 proposed to try to understand these anxieties and inhibitions and confer with parents, psychologists, or social workers (cf. MS12, MS14).

Another mental barrier was the lack of self-discipline (Ba9). T7 observed that students struggle to motivate themselves to carry out healthy practices. They missed the mental strength to “see things through” if they “do not feel like it” (T7 24:20). As T2 and T11 pointed out, this barrier is prevalent, and they could relate to that. In particular, T2 explained the gap between knowledge and behavior with this barrier: “One knows a lot, one could write a book about it, but one might be inconsequent.” (T2 03:51). Overcoming this lack of self-discipline was perceived as “rather very difficult through to impossible” (T7 25:35). T7 suggested analyzing “enhancers” for the “tendency of doing as one pleases” (by which is meant unhealthy behavior) in order to counteract these enhancers (T7 26:25). Furthermore, self-discipline had to be trained at an early stage (cf. Ef1; T7).

Pupils sometimes reject healthy practices (Ba2), for example, in the field of nutrition and an active lifestyle. Teachers observed that students did not aspire to eat healthy food but instead avoided or even rejected dishes regarded as healthy (T2, 5, 9, 11). T5, for instance, reported that students refused meals because of these meals “looking too healthy“ (T5 13:22). Additionally, diet was seen as a “very delicate topic because children want to distinguish themselves through the way they eat“ (T2 21:35), and therefore students might disapprove of healthy food. With increasing age, an active lifestyle might be rejected of as well: “And at some point, it gets unattractive to exercise. Well, the older they become, right? The less attractive it gets. Then, they don’t want to ride their bike anymore, they want to ride a moped.” (T11 45:05). Similarly, active breaks (MS21) might be perceived as “silly“ and the teachers should be aware of that (T7). Another factor that caused the refusal of healthy practices was prejudice in general (T10). Situations in which the rejection of healthy practices occurs were regarded as “difficult“ (T10 27:59). However, teachers still found ways to deal with them. For instance, teachers encouraged their pupils to try food they had rejected before, which might change their perception of healthy dishes (cf. MS8; T5, 9, 11).

Even if healthy food was not rejected, students might still neglect these food choices due to their competition with unhealthy food, which some students perceived as more attractive (Ba5; T3, 5, 9). For example, although vegetables were not generally disapproved of, they were not seen as being “as delicious as the kebab from around the corner, as the crisps that I can buy“ (T3 03:22). To encounter these tendencies, teachers prepared popular fast foods in a healthier version with the students at school (cf. MS1, MS8). Attractiveness did not only apply to unhealthy food but also to smoking. It is “not always cool to do just the healthy stuff. Smoking a cigarette once in a while and so on is, at that age, 16, 15 or so, of course they think it is cooler” (T8 11:38).

The following five barriers can be assigned to circumstances: Two different social environments (Ba3) were mentioned as potential barriers to a health-promoting lifestyle with the family on the one hand and the peers on the other (cf. MS12). T2 stated that parents have a tremendous impact on their children’s lifestyles. However, not all parents might be suitable role models for a healthy lifestyle (T3, 11), which underlines the importance of teachers exemplifying healthy behavior (cf. MS7). Some parents did not apply enough effort to support their children or implement a healthy lifestyle within their families (T3–6, 11). For example: “If the parents don’t take action [...], if the children are allowed to play computer games as long as they want and no exercising takes place, then it is nearly impossible for us to reach them.” (T4 05:42) or “When they play table tennis, some of them become really good at it. Then we said ‘why don’t you join a sports club?’. They don’t carry it out. The parents are unable to register their children there.” (T11 45:29). Peers are the other important part of the student’s social environment, as adolescents are very influential. Students displaying unhealthy habits could entice their fellow students into copying “cool” behavior (T2, 4, 8). “It is also an identification. If others do this, one wants to do it, too. One doesn’t want to be perceived as a health fanatic.” (T2 04:48). For teachers, it was not easy to encourage healthy practices in these cases: “Of course, it is really hard to ensure that other students say ‘That is not good’, instead they say ‘Oh, he has got crisps, I want crisps, too.’” (T4 05:58).

Established unhealthy habits (Ba4) were another barrier preventing the pupils from sustainably applying a healthy lifestyle and leading to the neglect of healthy practices or food. Changing these habits was difficult (T2–4, 11). However, clear rules in the school could help overcome unhealthy habits: “For example, during the lessons, students are only allowed to drink water. Then, the children can drink water or nothing. But not the lemonade they brought with them, and these are measures that I can influence to a certain extend.” (T4 29:22). Further measures included creating opportunities to leave the comfort zone, persuasion, and positive examples so students can experience a health-promoting lifestyle (cf. MS1, MS9; T2, 9, 11).

Additionally, physical barriers (Ba8) were mentioned (T4). Disabilities could be challenging for teachers, as they might not have the level of expertise to foster those students adequately. Then teachers had “to try to work as good as possible within these boundaries“ (T4 26:46). Moreover, teachers were sometimes confronted with pupils that were in impaired physical shape: “It gets difficult, if one [a student] is for example unable to walk for 2 km due to a lack of fitness, then it gets extremely difficult regarding the physical barrier, if it is not inclusion, but if it is just, yeah, a lack of fitness.” (T4 28:25).

Expenditure (Ba6) was another inhibitor of a health-promoting lifestyle. For example, “Of course, healthy food is more expensive than unhealthy food. For instance, crisps are cheaper than buying fruits or vegetables. Especially if you want to turn to organic food. I’m sure this is a huge barrier because we have families who don’t have much money, which makes it difficult for them to model this healthy lifestyle.” (T3 15:40). T3 described a project realized in school that provides access to fruits at comparatively low costs as a possible strategy to cope with that barrier (cf. ORL1, MS9).

Another named barrier was the unsuitability for everyday use (Ba7) of healthy practices. For instance, students spend most of their time in school and, therefore, have less time for physical activity outside school: “[I]n all-day school, the time for the pupils is limited. One shouldn’t neglect that. Nevertheless, I think it is very important that the students still have the opportunity to visit a sports club or the sports club come to school.” (T4 10:00). Thus, the importance of implementing health-promoting behaviors in everyday school life was highlighted (cf. MS9, ORL1, ORL3). Furthermore, preparing healthy dishes also required time, which was considered one reason for the success of fast food (T5).

5.3.2. Enablers (En)

Teachers mentioned six groups of enablers (En) that encourage pupils to make healthy lifestyle choices (see

Figure 4). They argued that a healthy lifestyle is visible through an externally

attractive appearance (En1; T5, 7). Therefore, students might be impressed: “[I]f you are healthy, you also exude that and that can be via skin, the hair, all kind of things, body form. If you avoid certain things, may it be smoking, you smell better and it is better for your teeth and everything else.” (T5 20:40). A healthy diet, physical activity, and not smoking are aspects of a healthy lifestyle that can improve or maintain attractiveness (T4, 5, 7) and therefore, healthy practices could themselves appear attractive (cf. MS8). In addition, T4 pointed out that “everyone wants to look attractive“ (T4 30:42), underscoring this enabler’s potential impact. However, teachers should be aware that some beauty ideals can be exaggerated and not achieved through healthy practices but through harmful ones (T4). In addition, implementing a healthy lifestyle could lead to

recognition by classmates (En2) in the form of acceptance or positive feedback, which is important for students (T5, 7). Acceptance may depend on outward appearance (En1): “Well, in class five was a case like that, of a boy, who was kind of podgy and always felt excluded. He recently dropped weight and is, gets better along with his peers. Unfortunately, children have the tendency to form groups and exclude others on the basis of the outer appearance” (T5 10:49). Furthermore,

good grades (En3) could be a solid motivation to internalize theoretical knowledge (cf. MS2) if tested in exams (T6, 8). The internal strive for

self-realization (En4) might also encourage healthy practices. Pupils might aspire to be more successful in sports, exercise regularly, and apply a healthy diet. They are challenged and motivated by opportunities to perform (cf. ORL1): “There are of course many sports projects at school. Like sports competitions and cups, bicycle races and so on, where we try to give people a stage to perform. Thus, being extremely motivated” (T7 28:08). Consequently, students could be proud of their achievements and boost their self-confidence (T3, 7, 8, 11). A healthy lifestyle was associated with an increase in overall

well-being (En5; T3). Drawing students’ attention to this by pointing out that “you notice that this is good for you” (T3 14:49) might encourage them to maintain or sustain health-promoting practices. T7 promotes the idea that physical activity reduces stress. Some pupils could be motivated to engage in healthy practices by the

social component (En6; T7). In many disciplines, training takes place in a group and thus offers the opportunity to get to know other people. At school, students were encouraged to participate in healthy extracurricular activities (ORL3) to integrate socially (T4).

5.3.3. Second Evaluation Step: Strategies to Overcome Student-Based Barriers

Our study does not only identify barriers, but also different ways to counteract these barriers. These are, on the one hand, various methods and strategies mentioned by the teachers in the interviews (

Figure 3) and, on the other hand, enablers (

Figure 4) that provide young people with a timely benefit that can be health-related but does not have to be. These

countermeasures to student-based barriers (referring to the methods and strategies named in

Figure 3) can be inductively structured into 5 groups, which refer to a

social,

temporal,

structural,

practice- and

benefit-related dimension.

Figure 5 shows these 5 dimensions as well as the subcategories (based on the teachers’ statements) from which the dimensions were derived.

The social dimension refers, on the one hand, to direct support in implementing health-promoting behavior, e.g., in the form of a social network (MS12; as far as it shares the idea of a healthy lifestyle), and, on the other hand, to indirect support caused by creating proximity to reality and authenticity, e.g., through positive role models (given by the teachers, MS7) or through experience reports provided by externals (MS14). The temporal dimension refers to an early start in health education (Ef1) to form positive habits as early as possible. Even if the second time-related subcategory, sustainability and endurance (MS16), was not mentioned in this context (i.e., overcoming barriers), it also belongs to this dimension, particularly because it was seen as an effective strategy by the teachers. The structural dimension involves creating opportunities to access health-promoting services, for example, on the one hand by providing appropriate infrastructure and terms of use in the school (MS9) and, on the other hand, by using certain longer-lasting teaching methods such as projects (ORL1) and extracurricular activities (ORL3). The practice-related dimension addresses acquiring health-related skills (practicing healthy behavior/MS1). Finally, there is the benefit-related dimension. It comprises benefits that are associated with health-promoting behavior, although these benefits do not necessarily relate to health but also to other areas of personal goals. These additional benefits make health-promoting behavior attractive to students and, thus, may act as enablers.

These

enablers mentioned by the teachers in the interviews (

Figure 4) can be arranged according to their importance on the basis of

Maslow’s pyramid of needs [

16]. An increase in well-being (En5) can be assigned to the level of basal needs (level 1 or 2) if a person’s well-being is currently severely impaired (otherwise, this enabler would belong to a less important level of need). The need for belonging (level 3) is addressed by allowing social contacts (En6) while applying health-promoting behaviors. A person’s need for esteem (level 4) may be satisfied if a healthy lifestyle leads to a more attractive appearance (Ef1), as this may be associated with more recognition by others, e.g., by classmates (En2). Good grades may also result in recognition (e.g., by parents). However, long-lasting health-promoting behavior is unlikely to be realized through grades, since behavior outside of school is not included in the grading. Offering the possibility of self-realization (En4, e.g., in that the health-promoting behavior goes hand in hand with a special hobby, such as a certain sport) corresponds to level 5 of Maslow’s pyramid of needs and thus is important, but not as central as the previously mentioned level of needs.