Abstract

The authors of this study aimed to evaluate the links between corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, trust, identification, and commitment to measure the impact of consumer perceptions of CSR initiatives on these three marketing outcomes (trust, identification, and commitment). A structured questionnaire was administered to 341 bank clients as part of an empirical study to examine the hypotheses. The study’s proposed model was tested in the Indian banking industry and examined the use of the structural equation modeling (SEM) method in the AMOS program. According to the findings, consumers believe that CSR initiatives significantly affect two marketing outcomes (trust and identification). The findings of this study are useful in helping policymakers at various banking institutions comprehend the major impact that CSR initiatives have on influencing consumer behavior. This study provides a greater knowledge of how consumers view CSR and how that impression may affect marketing outcomes.

1. Introduction

The concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has aroused a great deal of interest and concern among academics, businesspeople, and those working in the field of business administration. CSR is currently one of the most frequently cited justifications for building brands with distinctive personalities that meet customers’ self-definitional demands and promote positive identification with customers [1]. Recent research has shown that identification and business CSR image are positively correlated [2]. Marketing may be seen as a particular lens or set of “glasses” used to analyze the phenomenon of CSR [3]. In other words, concentrating on whether and how much CSR has been handled by marketing outcomes is insufficient [4]. Equally significant is how CSR is viewed via the marketing lens. What elements of the CSR construct, for instance, are reflected in and integrated into marketing outcomes? Although CSR has previously been discussed in the marketing literature, the focus has not yet been on the more critical and reflective components, such as how CSR views have been considered and how they have been incorporated into marketing outcomes [5]. A company’s adoption of CSR ideals frequently manifests itself in the form of marketing activities. The marketing outcomes and subsequent adoption of CSR concepts have an impact on how the company implements CSR. CSR is a vast and complex topic, thus its implementation in marketing is not straightforward. Different research has concentrated on various aspects of CSR [6]. Maignan and Ferrell [7] noted that the existing literature is unclear about the relationship between CSR and marketing outcomes and that studies in this area are barely comparable. This necessitates a comprehensive comprehension of CSR’s use in marketing. Pérez and Rodrguez [8] state that “CSR perceptions are regarded as a collection of beliefs (i.e., cognitive stage) that cause consumer affective responses (i.e., affective stage) and, in turn, affect customer behaviors (i.e., conative stage).” Few studies link customer perceptions of CSR with attitudes and intents such as satisfaction, consumer-organization fit, or trust, according to a thorough assessment of the CSR literature by Khan et al. [9]. In accordance with the hierarchy-of-effects method, we chose three emotional and conative reactions: commitment, identification, and trust. The authors of this study aim to evaluate the links between CSR activities and trust, identification, and commitment in order to measure the impact of consumer perception of CSR initiatives on these three marketing outcomes (trust, identification, and commitment). The retail banking sector in India was selected as the study’s context. Indian banks are known for their uniformity of goods and services and fierce competition [10]. The authors seek novel approaches to aid banks in establishing a positive reputation and successful marketing outcomes.

Banks have been compelled to strategically reposition themselves by implementing CSR policies that not only stop the recurrence of recent instances of irresponsibility but also rebuild their image and reputation by committing to improving the banking environment and upholding ethical principles. Banks must actively safeguard the environment, care for their people, conduct business ethically, and cultivate their reputation as contributors to society’s well-being in this new environment of competition [11]. As a result, CSR has grown to be a significant part of banks’ corporate identities and a crucial source of competitive advantage. Banks are making significant investments to present a distinctive image to their stakeholders by encouraging social responsibility [12,13]. Customers expect businesses to uphold social values as part of their social responsibility [14]. According to Pérez and Rodriguez’s [15] analysis of the banking industry, a CSR strategy is an effective differentiator when the goods and services provided by rival companies are largely standardized. When picking a financial product or service, Tinker and Banner [16] discovered that nearly 70% of their sample of Australian bank customers were impacted by the bank’s CSR program. This study provides a greater knowledge of how consumers view CSR and how that impression may affect marketing outcomes.

The remaining sections of the paper are as follows. We give our theoretical foundation and hypothesis in the next part. We go over the measurements, sample, and data-gathering process in the methodology section. The statistical results are presented in the section that follows. Finally, we discuss the study’s results, their theoretical and managerial implications, and potential directions for future research.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

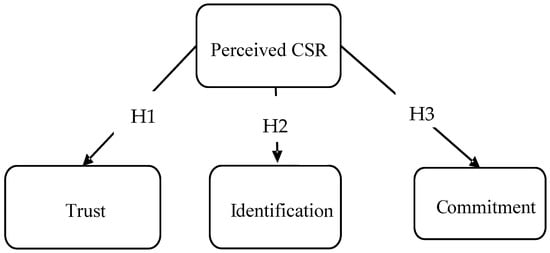

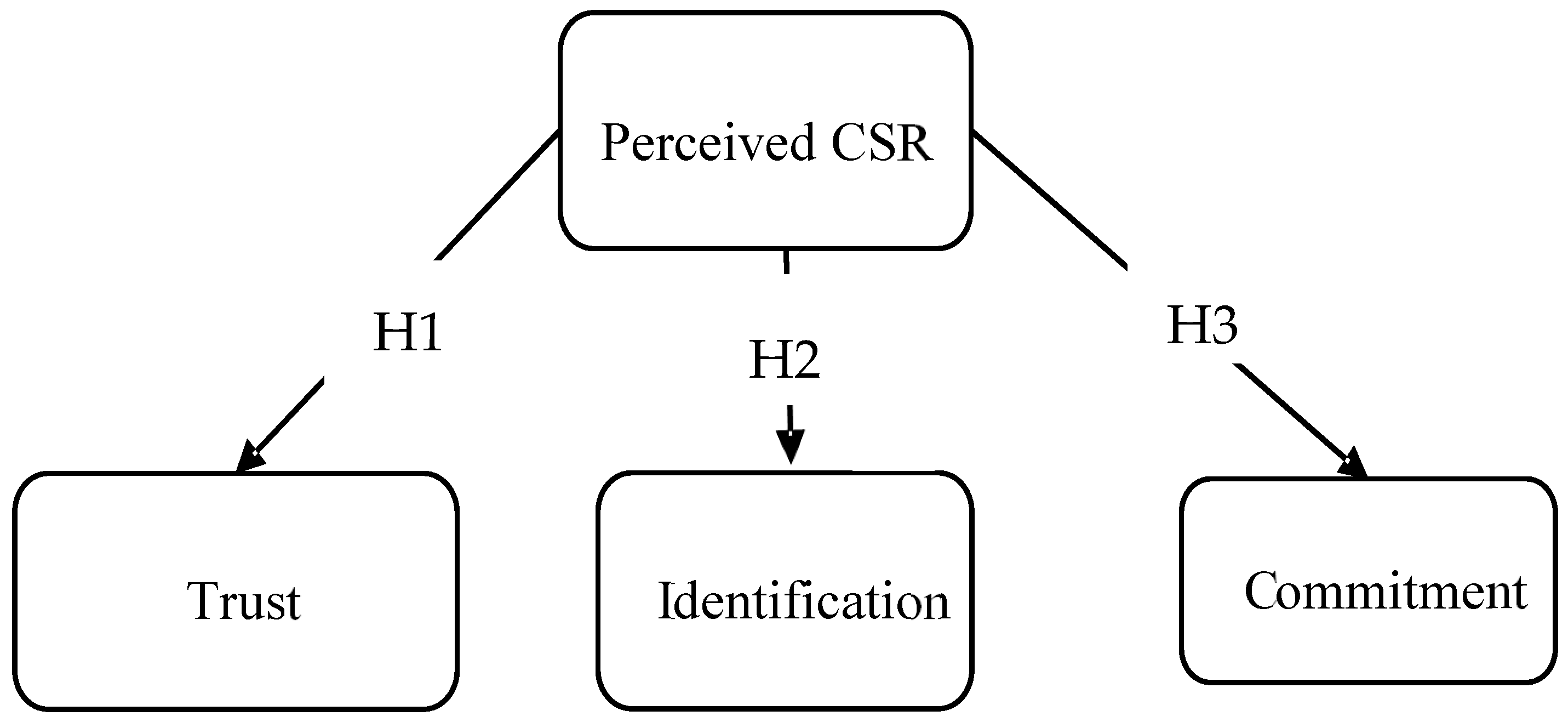

Prior consumer research has shown that CSR includes a variety of acts that reflect a company’s commitment to social responsibility, with a focus on how consumers perceive these activities [17]. These perceptions are known as perceived CSR, which is defined as consumers’ assessments of how well a firm satisfies its stakeholder expectations and societal obligations by participating in a wide range of voluntary activities [18]. The company’s activities for the well-being of its stakeholders through integrated strategies and practices are known as CSR [19]. Over the past three decades, the CSR literature has steadily grown, advancing the CSR discussion [20,21]. Similarly, over the past five years, there has been a notable increase in the micro-CSR literature, which focuses on researching how CSR affects consumers’ attitudes and behaviors. Customers develop an emotional bond with a firm when they see its CSR initiatives and believe that it is acting in its best interests [22]. They think that the company’s goals and their own goals are mutually exclusive. They enjoy being involved with the business and feel a sense of ownership over it, seeing the business and themselves as one unit [23]. Customers obtain confidence from CSR that the business will not take advantage of them [24,25] and feel comfortable forging intimate bonds with the business. CSR increases consumer trust, identification, and commitment by fostering sentiments of love, unity, and reliability. The conceptual framework is shown in Figure 1.

2.1. Trust

According to academic literature, trust is necessary for the development and maintenance of long-term relationships between a company and its customers, particularly in the setting of service markets [26]. A conviction that the provider of the good or service can be trusted to act in a way that serves the customers’ long-term interests is known as “consumer trust” [27]. In the empirical marketing literature, relationship marketing theory has received strong support, and it has been empirically shown that trust is a key mediator between business operations and customer loyalty [28]. Two elements of trust are thought to exist: performance or credibility trust, and benevolence trust [29]. Competence trust implies that the client has confidence in the company’s abilities, infrastructure, personnel, and ability to give customers the information and services they expect. Second, benevolence trust refers to the customer’s dependence on the company’s concern, care, honesty, and kindness. Customers’ trust in the company’s good intentions refers to their confidence that the business will behave competently and dependably as well as with their best interests in mind when making service-related decisions and delivering services [30].

2.2. CSR and Trust

Trust in CSR is defined as a person’s deep belief in the validity of an organization’s claims regarding its CSR operations. Through communication, stakeholders’ trust in an organization can be built up and strengthened, and this trust is frequently impacted by the organization’s communication strategy [31]. The availability of shared values between a corporation and its customers has an impact on consumer trust [26]. Regarding CSR initiatives, this behavior reveals information about corporate character and values and is helpful for increasing public trust in the company [32] (Brown and Dacin, 1997). According to Pivato et al., [33], businesses can increase the trust of all stakeholders, including customers, by incorporating moral and ethical standards into their strategic decision-making processes. The perception that a corporation is ethical and responsible fosters trust-based partnerships rooted in the belief that all exchange partners’ acts will be believable beyond any contractual or legal limits [34]. As Pivato et al. [33] (p. 5) suggested “the creation of trust is one of the most immediate consequences of a company’s social performance”. Therefore, we propose the following research hypothesis:

H1.

Consumer perception of CSR has a positive influence on their trust in the company.

2.3. Identification

The primary theoretical framework for identification research in management and marketing is social identity theory [35]. Social identity theory, which predicts intergroup actions based on perceived group affiliation, is the foundation of identification. Individuals “create self-conceptions inter alia through their affiliation or connection with particular social groups,” according to social identity academics, and it appears that social systems exist in organizations where people establish their self-conceptions. Due to the demand for self-distinctiveness, self-categorization, and self-enhancement, customers frequently identify with companies. They meet these requirements by collaborating with well-known, reputable, and famous organizations [36]. Consumers are more likely to believe that a company has an acceptable quality that mirrors their self-concept if it is seen as socially desirable. The motivations and causes that lead people to identify with certain brands and businesses have been studied in the identification study.

2.4. CSR and Identification

A company’s CSR activities improve the reputation and positive image of the company [37], and consumers’ positive perceptions help them to better categorize and differentiate themselves. Previous studies provided empirical support that CSR positively impacts identification [38]. CSR initiatives help a firm distinguish itself from its competitors by fostering a positive reputation and prestige. Because it satisfies their need for self-worth and self-esteem, this reputation and prestige allow consumers to perceive the company as having high status and great worth, resulting in organizational pride [36]. We contend that CSR acts as a catalyst for customers who identify strongly with a brand and that it encourages them to consider themselves a part of this entity. They might think of themselves in terms of their organization, and a portion of their identity comes from belonging to that group. Some may perceive an evaluation of the company’s CSR efforts as personal praise. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2.

Consumer perception of CSR has a positive influence on their identification with the company.

2.5. Commitment

According to Anderson and Weitz [39], commitment is defined as promises or sacrifices made in the short term but carried out in a relationship that improves in the long term, and enhances mutual gain in transactions. Loyalty and satisfaction are frequently studied in the context of commitment. The desire to keep a relationship going is a widely accepted definition of commitment [26]. To put it another way, commitment is the desire to maintain a connection due to its deemed intrinsic value. Buyers and sellers are more receptive to collaboration when they are dedicated to the partnership [26]. They consequently grow more adaptable. As a strong sense of commitment is positively correlated with customer pleasure, which is frequently a precursor to commitment, businesses can use this to strengthen their ties with their customers.

2.6. CSR and Commitment

According to research, customers typically reward companies that take socially responsible actions and participate in CSR initiatives with their business or by having favorable sentiments toward that company. Because high customer acquisition costs are challenging to recover without the commitment and repeat business of the consumer, retailer loyalty is of great interest to retailers [40]. Therefore, commitment increases purchase intent while simultaneously lowering the possibility of losing customers to more compelling options. Bhattacharya et al. [41] proposed that the strength of a consumer’s relationships with a firm impacts how likely they are to engage in conduct beneficial to the company by applying the means-end chain model. Empirical data that support this assertion show that commitment affects client loyalty [42]. Customers’ commitment to the company is favorably correlated with their perceptions of CSR. As a result, the perception of socially responsible behavior might increase brand loyalty [43]. For instance, Bartikowski and Walsh [44] contend that social responsibility, a component of business reputation based on customer satisfaction, has a direct impact on consumers’ affective commitment. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3.

Consumer perception of CSR has a positive influence on their commitment to the company.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

The Indian banking sector was chosen for the present study. The banking sector in developing economies such as India provides the framework for the expansion and development of other businesses. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the country’s banking regulatory body, has issued guidelines stating that Indian banks must be dedicated to “sustainability,” “do[ing] no harm,” and “responsibility,” broadly advising banks to maximize the vision of social and environmental sustainability in their operations and the operations of the businesses they lend to. The issue can be addressed by focusing more on a customer-driven strategy by banking organizations in the current sustainable and socially responsible period. This is due to the increase in funding for CSR activities by banks in various projects.

The target sample for the study consisted of retail banking customers who lived in Delhi, the capital of India with a population of 200 million. The survey’s respondents were chosen using a non-probabilistic method. The cost and time effectiveness of the convenience sampling technique led to its selection. Respondents include customers of banking services over the age of 18 years who have held an account with the bank for the last year. Personal surveys were used to distribute the final questionnaire. Respondents were personally approached at the different bank branches during the working day. A total of 390 people were initially chosen as the sample. Around 90 percent, or 341 usable respondents, were included in the primary study after deleting the missing and incomplete responses. The sample is representative of the population in terms of its demographic characteristics. Of the participants, 33.23% were female and 66.77% were male; 41.2% were aged between 18 and 34; and most had acquired a university degree (58.8%) as their greatest level of schooling. In addition, 34.5% had a net income of between 50,000 to 90,000 INR (monthly).

3.2. Scale Items

All assessment items were evaluated on a seven-point Likert scale, with the options “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree.” Appendix A contains a complete list of the measurement items that were employed. Consumer perception of CSR was measured with the four-item scale adapted from [32,45]. A four-item scale based on [46] was used to measure identification. A four-item scale was used to measure trust adapted from the work of [26,29]. We utilized a three-item scale adapted from Meyer and Allen [47] to measure commitment.

4. Results and Analysis

The two-stage method of Anderson and Gerbing [48] was used for the analysis. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to examine the psychometric validity of the measuring tool, and structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the structural relationships among the theoretically postulated latent variables. SEM has three key advantages: (1) explicit measurement error assessment; (2) estimation of latent (unobserved) variables via observed variables; and (3) model testing, where a structure can be imposed and its data fit is evaluated.

4.1. CFA Results

We first looked for any indications of multicollinearity by evaluating the variance inflation factor among latent variables in our suggested overall model. Values were below 10, indicating multicollinearity was not a problem in our investigation [49]. The latent variables in the proposed model were also subjected to Harman’s single-factor test to rule out bias due to common data-gathering methods [50]. With the factor structure suggested by the study, the overall fit was noticeably worse than the findings of the CFA. These findings suggest that a single factor misrepresents the data, suggesting that there may be no common method bias in the data collection. The findings of the confirmatory factor analysis indicated a good model fit with the following values: (χ2 = 171.035, 2/df = 84, CFI = 0.977, and GFI = 0.938). For the confirmation of convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) must be greater than 0.50, factor loadings must be significantly higher than 0.50, and factor composite reliabilities must be at least 0.60, according to Fornell and Larcker [51]. Our findings demonstrated that our measuring scales have convergent validity (Table 1). Additionally, when AVE values are greater than the squared correlation estimations, discriminant validity is maintained [49]. The AVEs of all constructs exceed their corresponding squared correlations for each construct pair, as shown in Table 2, demonstrating the discriminant validity of our measures.

Table 1.

CFA results.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity results.

4.2. SEM and Hypotheses Results

The structural model was examined in order to estimate the potential links between constructs. The SEM has a good model fit (χ2 = 220.777, 2/df = 87, CFI = 0.965, and GFI = 0.919). The estimated path coefficient values empirically validated all of the direct effects in our proposed model at a significance level of 0.05. The path relationship’s hypotheses were all confirmed to be significant (Table 3). According to the findings, trust is positively and significantly impacted by consumer perceptions of CSR (β = 0.325, p < 0.001); thus, hypothesis 1 is supported. H2 was supported by the findings of a substantial and favorable path association between CSR and identification (β = 0.229, p ≤ 0.005). H3, which asserts a direct and favorable association between CSR and commitment, which was not significant (β = 0.025, p = 0.752), is hence not supported by the results.

Table 3.

SEM results.

5. Discussion

This study explores the various effects of CSR on marketing outcomes and contributes to the body of CSR literature. This study was the first to propose and evaluate the theoretical model based on direct links between CSR and marketing outcomes. However, almost all of the literature that has addressed this subject to this point has focused on industrialized economies. Given that economic growth, production, and consumption patterns can result in negative externalities such as wealth inequality, pollution, and the depletion of natural resources, analyzing the case of growing economies such as India is incredibly important [52,53]. It is crucial to understand how customers in emerging economies view and value businesses’ CSR or sustainable initiatives as consumers. Our findings are insightful because they demonstrate that, as is consistent with the body of literature, consumers in these economies have a favorable view of CSR. The current study evaluates how CSR is seen by consumers as contributing to their commitment to, and trust in, banks. The causal link between perceived CSR, trust, identification, and commitment is examined. This study indicated that because consumers believe CSR messages to be authentic, CSR actions positively enhance consumer identification. Customers are more likely to link themselves with banks that engage in CSR initiatives that support their sense of self-worth and self-improvement. CSR initiatives are a powerful tool for improving customer identification. Companies that practice social responsibility show concern for all of their stakeholders, which not only benefits those stakeholders but also benefits the businesses in the form of successful marketing outcomes. CSR has an impact on customers beyond their purchasing choices.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This study’s main goal was to investigate how CSR affected consumer marketing outcomes (trust, identity, and commitment). A sample of Indian bank customers was used to test the proposed model to determine how their opinions of the banks’ CSR initiatives affect these relationships. Based on the theoretical contributions of the hierarchy of effects model, the study’s findings support the claim that consumer trust and identification are influenced by CSR perceptions. The findings of this research add to a deeper understanding of how CSR perceptions might favorably affect customer trust and identification because few prior studies have investigated the role of CSR perceptions in the banking industry. The findings can be generalized in the context of the banking industry in emerging economies in light of the findings. The study’s quality and sampling methodology from India’s metropolitan and smart cities show that there is a cultural diversity of samples that can be used to reflect the country’s population as a whole. The banking industry’s decision-makers have advocated for more focus to be placed on social responsibility initiatives. The outcome will assist the banks in internalizing and fulfilling the social component of the banks as it has a significant influence on the various marketing outcomes. Banks in developing nations should invest in CSR since they are also interested in it. It is obvious that CSR needs to be given considerable attention if banks are to win back their customers’ trust. The study’s results also seem to indicate that bank clients are aware of the need for banks to follow local laws. Non-compliance can have a negative effect on customers’ trust in banks. Financial indicators are typically used to evaluate financial institutions. According to the findings, bank customers and other interested parties may start to demand that their banks make investments in social and environmental causes in order to enhance their marketing outcomes. With the use of an inductive, analytical approach that banks may use to better align their CSR investment to achieve the desired marketing results, this study makes significant contributions to improving the effectiveness of CSR programs. It has long been believed that banks are primarily connected with rational qualities such as friendly customer service, high-quality goods, and financial viability. In light of the findings in this paper, we believe CSR is also crucial for banks when attempting to win back the loyalty or commitment and trust of their customers and society.

However, a more thorough approach to Indian CSR for Indian banks will offer much-needed synergy between businesses and society. Businesses will be able to better leverage their CSR expenditures if they make an effort to match their business plan with their CSR strategy. Additionally, adopting an ROI methodology that measures investments as potential costs for society and returns as the generation of socioeconomic value may be helpful. We, therefore, propose a change in direction for Indian banks’ strategy and strategic CSR activities and emphasis in India.

In addition to the study’s important contribution, a few limitations exist that may open up new research directions: First, to predict the relationship between consumer perception of CSR and corporate marketing outcomes, future research may look at the effects of brand level (such as brand position in the marketplace) and consumer demographic characteristics. Second, future research could evaluate this model utilizing data from multiple contexts, such as various business subsectors, in order to generalize the results. Third, to develop a more comprehensive framework and provide more information on the causes and benefits of CSR, future research may include more social exchange factors such as customer loyalty, brand love, and brand passion. Fourth, the present study used the convenience sampling method to select the respondents. Further research may collect responses through any of the random sampling methods which have more generalizability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.; Software, I.K.; Formal analysis, I.K.; Investigation, M.F.; Writing—original draft, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Prince Sultan University for paying the Article Processing Charges (APC) of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Construct | Scale Items | Source |

| CSR | “my bank is socially responsible” | Brown and Dacin, [32] and Klein and Dawar, [45] |

| “my bank contributes to the welfare of society” | ||

| “my bank contributes to the donation program” | ||

| “my bank doesn’t harm the environment” | ||

| Trust | “I trust on the quality of this banking company” | Morgan and Hunt, [26] and Sirdeshmukh et al., [29] |

| “is interested in its customers” | ||

| “is honest with its customers” | ||

| “make me feel a sense of security” | ||

| Commitment | “I really feel as if this [bank’s] problems are my own” | Meyer and Allen [47] |

| “I feel like “part of the family” at our [bank]” | ||

| “I feel that I have too few options to consider leaving this [bank]” | ||

| “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my life with this [bank]” | ||

| Identification | “I identify strongly with my bank” | Stokburger-Sauer, N., Ratneshwar, S., and Sen, S. [47] |

| “my bank is like a part of me” | ||

| “my bank has a great deal of personal meaning for me” | ||

| “I feel a strong sense of belonging to my bank” |

References

- Hur, W.M.; Moon, T.W.; Kim, H. When and how does customer engagement in CSR initiatives lead to greater CSR participation? The role of CSR credibility and customer–company identification. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1878–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ahmad, S. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility, Consumer Identification and Purchasing Intention. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Jha, A. Corporate social responsibility in marketing: A review of the state-of-the-art literature. J. Soc. Mark. 2019, 9, 418–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Rahman, Z. An integrated framework to understand how consumer-perceived ethicality influences consumer hotel brand loyalty. Serv. Sci. 2017, 9, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I. An investigation of consumer evaluation of authenticity of their company’s CSR engagement. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2022, 33, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, S.; Bae, Y.H.; Lim, H.; Kwon, J. The role of marketing capability in linking CSR to corporate financial performance: When CSR gives positive signals to stakeholders. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 1333–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C.; Ferrell, L. A stakeholder model for implementing social responsibility in marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 956–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. Personal traits and customer responses to CSR perceptions in the banking sector. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Ferguson, D.; Pérez, A. Customer responses to CSR in the Pakistani banking industry. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I.; Kumar, V.; Shrivastava, A.K. Corporate social responsibility and customer-citizenship behaviors: The role of customer–company identification. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2022, 34, 858–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bihari, S.C.; Pradhan, S. CSR and performance: The story of banks in India. J. Transnatl. Manag. 2011, 16, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, V.I.; Scholtens, B. Corporate social responsibility policies of commercial banks in developing countries. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Brand Advocacy among Consumers: The Mediating Role of Brand Trust. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. Measuring CSR image: Three studies to develop and to validate a reliable measurement tool. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinker, M.; Banner, L. Consumer purchasing decisions in financial institutions: Corporate social responsibility strategy. GSTF J. Bus. Rev. 2017, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I.; Rahman, Z. Striving for legitimacy through CSR: An exploration of employees responses in controversial industry sector. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 15, 924–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Corporate social responsibility and bank customer satisfaction: A research agenda. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2008, 26, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croker, N.C.; Barnes, L.R. Epistemological development of corporate social responsibility: The evolution continues. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, A.; Metwally, A.B.M. Institutional complexity and CSR practices: Evidence from a developing country. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 10, 655–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Wong, I.A.; Shi, G.; Chu, R.; Brock, J.L. The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance and perceived brand quality on customer-based brand preference. J. Serv. Mark. 2014, 28, 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Nurunnabi, M.; Alfakhri, Y.; Alfakhri, D.H. Consumer perceptions and corporate social responsibility: What we know so far. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2018, 15, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Islam, R.; Pitafi, A.H.; Xiaobei, L.; Rehmani, M.; Irfan, M.; Mubarak, M.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer loyalty: The mediating role of corporate reputation, customer satisfaction, and trust. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Nazir, M.S.; Ali, I.; Nurunnabi, M.; Khalid, A.; Shaukat, M.Z. Investing in CSR pays you back in many ways! The case of perceptual, attitudinal and behavioral outcomes of customers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.A.; Evans, K.R.; Cowles, D. Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonlertvanich, K. Service quality, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty: The moderating role of main-bank and wealth status. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 278–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdeshmukh, D.; Singh, J.; Sabol, B. Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugandwa, T.C.; Kanyurhi, E.B.; Bugandwa Mungu Akonkwa, D.; Haguma Mushigo, B. Linking corporate social responsibility to trust in the banking sector: Exploring disaggregated relations. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 592–617. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, C. Corporate social responsibilities, consumer trust and corporate reputation: South Korean consumers’ perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivato, S.; Misani, N.; Tencati, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust: The case of organic food. Business ethics: A European review. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2008, 17, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Florencio, B.; Garcia del Junco, J.; Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Rosa-Díaz, I.M. Trust as mediator of corporate social responsibility, image and loyalty in the hotel sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1273–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organizational identity: A reader. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; Volume 56, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer–company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aledo-Ruiz, M.D.; Martínez-Caro, E.; Santos-Jaén, J.M. The influence of corporate social responsibility on students’ emotional appeal in the HEIs: The mediating effect of reputation and corporate image. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; He, H.; Mellahi, K. Corporate social responsibility, employee organizational identification, and creative effort: The moderating impact of corporate ability. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 323–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Weitz, B. The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amine, A. Consumers’ true brand loyalty: The central role of commitment. J. Strateg. Mark. 1998, 6, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D.; Sen, S. Strengthening stakeholder–company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Sramek, B.; Droge, C.; Mentzer, J.T.; Myers, M.B. Creating commitment and loyalty behavior among retailers: What are the roles of service quality and satisfaction? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 37, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osakwe, C.N.; Yusuf, T.O. CSR: A roadmap towards customer loyalty. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2021, 32, 1424–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartikowski, B.; Walsh, G. Investigating mediators between corporate reputation and customer citizenship behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Dawar, N. Corporate social responsibility and consumers’ attributions and brand evaluations in a product–harm crisis. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokburger-Sauer, N.; Ratneshwar, S.; Sen, S. Drivers of consumer–brand identification. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research and Application; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Fatma, M. Online destination brand experience and authenticity: Does individualism-collectivism orientation matter? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Rahman, Z. Brand experience and emotional attachment in services: The moderating role of gender. Serv. Sci. 2017, 9, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).