Acquisition and Utilization of Chinese Peasant e-Entrepreneurs’ Online Social Capital: The Moderating Effect of Offline Social Capital

Abstract

:1. Introduction

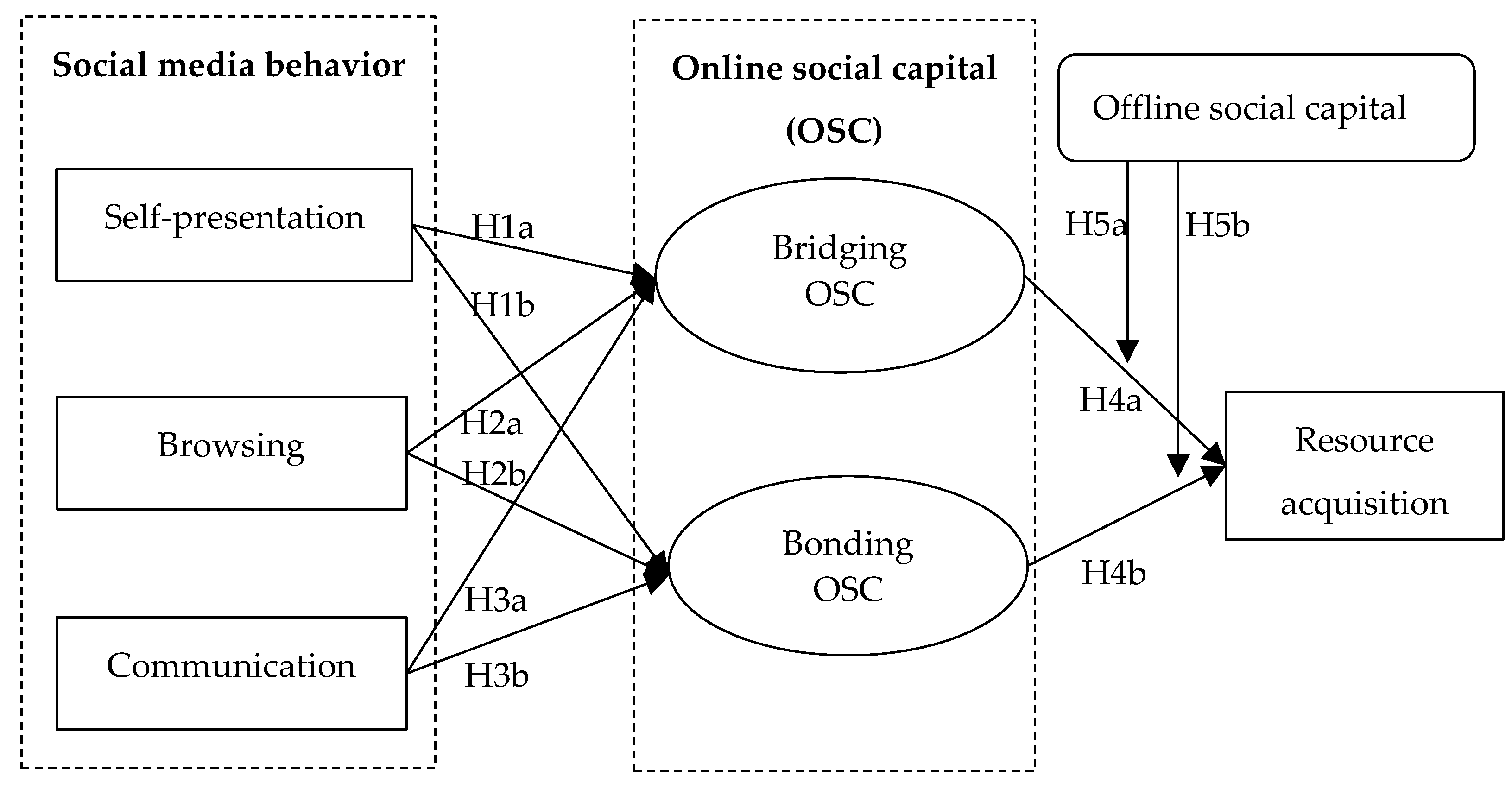

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Online Social Capital

2.2. Social Media Behavior and OSC

2.2.1. Self-Presentation Behaviors and OSC

2.2.2. Browsing Behaviors and OSC

2.2.3. Communication Behaviors and OSC

2.3. OSC and Resource Acquisition

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Offline Social Capital

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Resources

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Social Media Behaviors

3.2.2. Online Social Capital

3.2.3. Resource Acquisition

3.2.4. Offline Social Capital

3.2.5. Control Variable

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2. Common Method Bias

4.3. Results of Hypothesis Test

4.3.1. Results of Main Effect Test

4.3.2. Results of Moderating Effect Test

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kimmitt, J.; Muñoz, P.; Newbery, R. Poverty and the varieties of entrepreneurship in the pursuit of prosperity. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 35, 105939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.A.; Lai, F.W.; Asif, M.; Akhtar, S.; Ullah, S. Embedding sustainability into bank strategy: Implications for sustainable development goals reporting. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, C.; Bruton, G.D.; Chen, J. Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soluk, J.; Kammerlander, N.; Darwin, S. Digital entrepreneurship in developing countries: The role of institutional voids. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 170, 120876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.A.; Lai, F.W.; Siddique, J.; Zahid, M.; Ali, S.E.A. A walk of corporate sustainability towards sustainable development: A bibliometric analysis of literature from 2005 to 2021. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 30, 36521–36532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.D.; Huang, J.K.; Scott, R. Study on geographical location transportation infrastructure and planting structure adjustment. Manag. World 2006, 9, 59–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Horng, S.-M.; Wu, C.-L. How behaviors on social network sites and online social capital influence social commerce intentions. Inf. Manag. 2019, 57, 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.; Wallace, C.; Smart, A.; Norman, T. Building Virtual Bridges: How Rural Micro-Enterprises Develop Social Capital in Online and Face-to-Face Settings. Sociol. Rural. 2014, 56, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tiwari, S.; Lane, M.; Alam, K. Do social networking sites build and maintain social capital online in rural communities? J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 66, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y. The role of online social capital in the relationship between Internet use and self-worth. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 40, 2073–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.C.; Chan, N.K. Predicting social capital on Facebook: The implications of use intensity, perceived content desirability, and Facebook-enabled communication practices. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurer, M.M.; Waldkirch, M.; Schou, P.K.; Bucher, E.L.; Burmeister-Lamp, K. Digital affordances: How entrepreneurs access support in online communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, X. The contribution of mobile social media to social capital and psychological well-being: Examining the role of communicative use, friending and self-disclosure. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S. Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spottswood, E.L.; Wohn, D.Y. Online social capital: Recent trends in research. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 36, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D. On and Off the ‘Net: Scales for Social Capital in an Online Era. J. Comput. commun. 2006, 2, 593–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Granovetter, M. The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited. Sociol. Theory 1983, 1, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Brown, B.B. Self-disclosure on social networking sites, positive feedback, and social capital among Chinese college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 38, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykov, Y.; Koltsova, O.; Sinyavskaya, Y. Effects of user behaviors on accumulation of social capital in an online social network. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guo, H.; Duan, Y. Self-presentation Strategy of WeChat Users with Motives Impact on the Formation of Online Social Capital. In 2nd International Symposium on Business Corporation and Development in South-East and South Asia under B&R Initiative (ISBCD 2017); Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burke, M.; Kraut, R.; Marlow, C. Social Capital on Facebook: Differentiating Uses and Users; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.; Kim, Y.J.; Ahn, J. How do people use Facebook features to manage social capital? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.-W.; Adler, P.S. Social Capital: Maturation of a Field of Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, H.X.; Wang, X.H.; Zhou, B.G. Relationship among Interaction, Presence and Consumer Trust in B2C Online Shopping. Manag. Rev. 2015, 27, 43–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.Q.; Zhai, S.J. Relational Embeddedness, Resources Acquisition and OFDI Firms’ International Performance. Manag Rev. 2020, 32, 29–39. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, N.B.; Gray, R.; Lampe, C.; Fiore, A.T. Social capital and resource requests on Facebook. New Media Soc. 2014, 16, 1104–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.G.; Smith, J.B. Founders’ uses of digital networks for resource acquisition: Extending network theory online. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 466–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. The Contingent Value of Social Capital. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The Benefits of Facebook “Friends:” Social Capital and College Students’ Use of Online Social Network Sites. J. Comput. Commun. 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerji, D.; Reimer, T. Startup founders and their LinkedIn connections: Are well-connected entrepreneurs more successful? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, S.Z.; Moran, P.; Zhong, X.; Bliemel, M.J. Reaching and Acquiring Valuable Resources: The Entrepreneur’s Use of Brokerage, Cohesion, and Embeddedness. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2016, 40, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Semrau, T.; Werner, A. How Exactly Do Network Relationships Pay Off? The Effects of Network Size and Relationship Quality on Access to Start–Up Resources. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 501–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S.L.; Tornikoski, E.T. Resource Acquisition in the Emergence Phase: Considering the Effects of Embeddedness and Resource Dependence. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 249–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Tuselmann, H.; Jayawarna, D.; Rouse, J. Effects of structural, relational and cognitive social capital on resource acquisition: A study of entrepreneurs residing in multiply deprived areas. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2018, 31, 534–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, A.; Buchta, C.; Hornik, K.; Mair, P. Making friends and communicating on Facebook: Implications for the access to social capital. Soc. Netw. 2014, 37, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afandi, E.; Kermani, M.; Mammadov, F. Social capital and entrepreneurial process. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 13, 685–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.C.; Rui, Z.Y.; Zeng, J.F. The impact of dual network embedded entrepreneurial resource acquisition on entrepreneurial ability of migrant workers based on an empirical analysis of 183 migrant workers in Jiangxi, Anhui and Jiangsu provinces. China Rural. Surv. 2014, 3, 29–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Y.H.; Wang, D.C.; Chi, F.M. Analysis of influencing factors of rural e-commerce based on structural equation Model—A case study of 15 demonstration counties of rural e-commerce in Heilongjiang Province. Agrotech. Econ. 2016, 8, 106–118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The Influence of Social Capital on the Growth of Farmers’ Professional Cooperatives: An Empirical Study Based on the Role of Resource Acquisition Intermediary. Issues Agric. Econ. 2019, 1, 125–133. (In Chinese)

- Yue, Z.; Xiang, N. Acquaintance Society: The Level and Differences of Village Social Capital. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 5, 66–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Research group of Rural Economic System and Management Department, Ministry of Agriculture; Zhang, H.Y. Investigation on the development of new farmers under the background of agricultural supply-side structural reform. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2016, 4, 2–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin, T. A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. J. Manag. 1995, 21, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, R.; Wright, P.C. CHENGE Business networking in the Chinese context. Manag. Res. News 2006, 29, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.L. Guanxi and Organizational Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2012, 8, 139–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, L. What do private firms do after losing political capital? Evidence from China. J. Corp. Financ. 2019, 60, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Q.; Hassan, H.; Ahmad, H. The Role of a Manager’s Intangible Capabilities in Resource Acquisition and Sustainable Competitive Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ju, W.; Zhou, X.; Wang, S. The impact of scholars’ guanxi networks on entrepreneurial performance—The mediating effect of resource acquisition. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2019, 521, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Fernandez, H.; Rodriguez Escudero, A.I.; Martin Cruz, N.; Delgado Garcia, J.B. The impact of social capital on entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents: Differences between social capital online and offline. Bus. Res. Q. 2021, 1544609438. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23409444211062228 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

| Variables | Category | Count | Percentage | Variables | Category | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 68 | 22.22% | Education | Under high school | 30 | 9.8% |

| Male | 238 | 77.78% | High school | 74 | 24.18% | ||

| Age | <30 | 69 | 22.55% | College | 100 | 32.68% | |

| 31~40 | 110 | 35.95% | Graduate | 83 | 27.12% | ||

| 41~50 | 94 | 30.72% | Master or above | 19 | 6.21% | ||

| >50 | 33 | 10.78% | Peasant e-entrepreneurs | Family farms | 146 | 47.71% | |

| Region | Eastern China | 83 | 27.12% | Cooperatives | 100 | 32.68% | |

| Central China | 90 | 29.41% | Platform | 39 | 12.75% | ||

| Western China | 133 | 43.46% | Large farming households | 21 | 6.86% |

| Constructs | Item | Questions | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Browsing (BR) | BR1 | I use WeChat to get information about the status of my peers. | [6,23] |

| BR2 | I use WeChat to get information about industry development. | ||

| BR3 | I use WeChat to get information about suppliers. | ||

| BR4 | I use WeChat to get information about inputs, such as agricultural materials and production technology. | ||

| BR5 | I use WeChat to get information about consumers. | ||

| BR6 | I use WeChat to get information about policies and regulations. | ||

| Self-presentation (SE) | SE1 | From my above profile, people can easily understand my characteristics | [13] |

| SE2 | I like to share my location on WeChat. | ||

| SE3 | I like to share my feelings on WeChat. | ||

| SE4 | I like to share my work process on WeChat. | ||

| SE5 | I like to share my life status on WeChat. | ||

| SE6 | I have clear personal information (age, occupation, contact, real name) on WeChat. | ||

| Communication (CO) | CO1 | I often comment on posts on WeChat. | [23] |

| CO2 | I often forward posts on WeChat. | ||

| CO3 | I often like posts on WeChat. | ||

| CO4 | I often chat with friends alone. |

| Latent Variables | Items | Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-presentation | SE1 | 0.770 | 0.874 | 0.905 | 0.614 |

| SE2 | 0.811 | ||||

| SE3 | 0.808 | ||||

| SE4 | 0.804 | ||||

| SE5 | 0.804 | ||||

| SE6 | 0.700 | ||||

| Browsing | BR1 | 0.885 | 0.910 | 0.930 | 0.690 |

| BR2 | 0.851 | ||||

| BR3 | 0.866 | ||||

| BR4 | 0.828 | ||||

| BR5 | 0.825 | ||||

| BR6 | 0.719 | ||||

| Communication | CO1 | 0.875 | 0.771 | 0.855 | 0.600 |

| CO2 | 0.834 | ||||

| CO3 | 0.840 | ||||

| CO4 | 0.580 | ||||

| Bridging OSC | BRSC1 | 0.908 | 0.937 | 0.952 | 0.798 |

| BRSC2 | 0.892 | ||||

| BRSC3 | 0.899 | ||||

| BRSC4 | 0.868 | ||||

| BRSC5 | 0.899 | ||||

| Bonding OSC | BOSC1 | 0.844 | 0.858 | 0.904 | 0.704 |

| BOSC2 | 0.891 | ||||

| BOSC3 | 0.876 | ||||

| BOSC4 | 0.736 | ||||

| Resource acquisition | RE1 | 0.729 | 0.898 | 0.925 | 0.711 |

| RE2 | 0.877 | ||||

| RE3 | 0.862 | ||||

| RE4 | 0.868 | ||||

| RE5 | 0.873 |

| Path Coefficient | Std. Error | T-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offline SC -> resource acquisition | 0.236 *** | 0.048 | 4.896 | 0.000 |

| Offline SC × bridging online SC -> resource acquisition | 0.078 | 0.055 | 1.415 | 0.157 |

| Offline SC × bonding online SC -> resource acquisition | −0.207 *** | 0.052 | 3.985 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Chen, W. Acquisition and Utilization of Chinese Peasant e-Entrepreneurs’ Online Social Capital: The Moderating Effect of Offline Social Capital. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6154. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076154

Li Y, Chen W. Acquisition and Utilization of Chinese Peasant e-Entrepreneurs’ Online Social Capital: The Moderating Effect of Offline Social Capital. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):6154. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076154

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yan, and Weiping Chen. 2023. "Acquisition and Utilization of Chinese Peasant e-Entrepreneurs’ Online Social Capital: The Moderating Effect of Offline Social Capital" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 6154. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076154