The Impact of External Shocks on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Linking the COVID-19 Pandemic to SDG Implementation at the Local Government Level

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

3. Determining the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on SDG Implementation

3.1. The Slowdown Effect: COVID-19 Slowed down Organizations’ SDG Implementation in General

3.2. The Prioritization and Acceleration Effect: COVID-19 Led Organizations to Prioritize Some SDGs and to Accelerate Their Organizational Implementation

3.3. The Postponement Effect: During COVID-19, Organizations Postponed Some SDG Implementation-Related Activities

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample and Procedures

4.2. Survey Design

5. Results

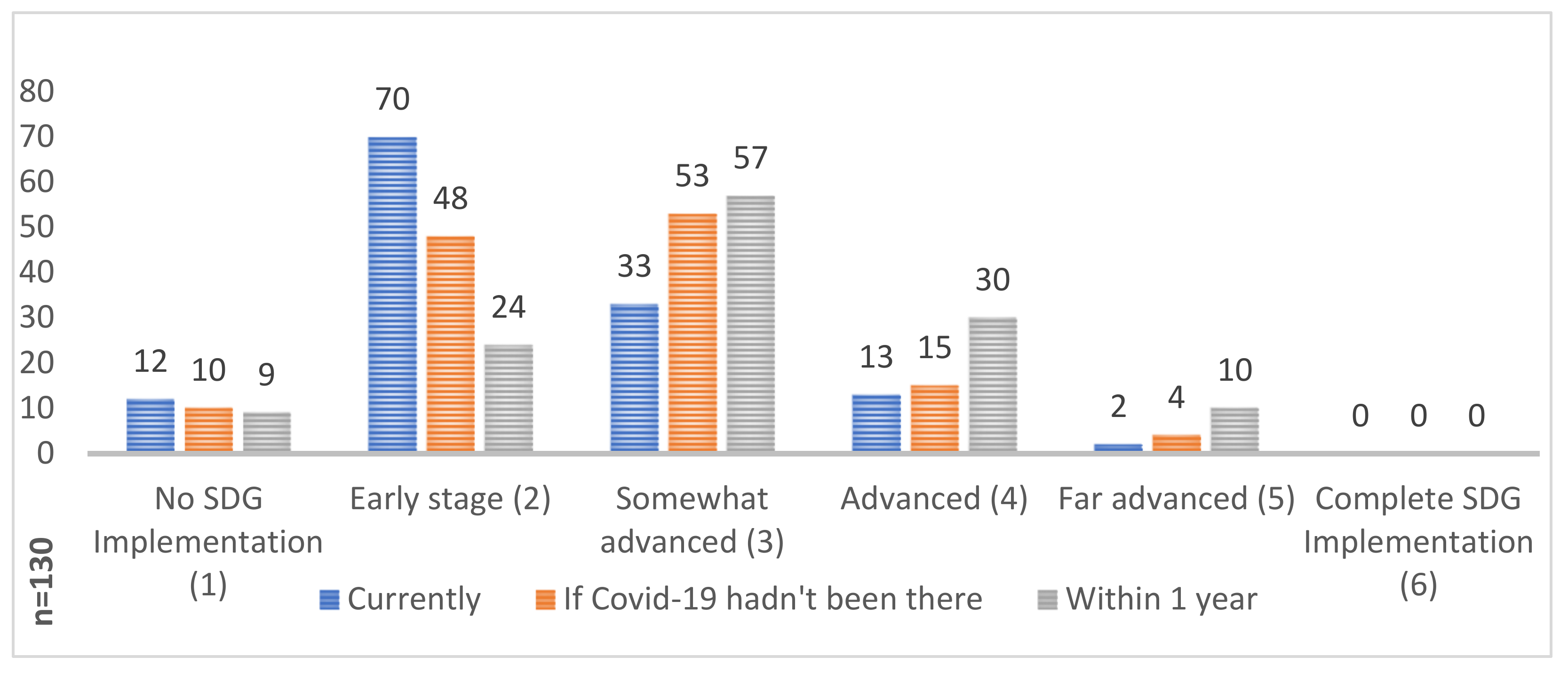

5.1. The Slowdown Effect

5.2. The Prioritization and Acceleration Effect

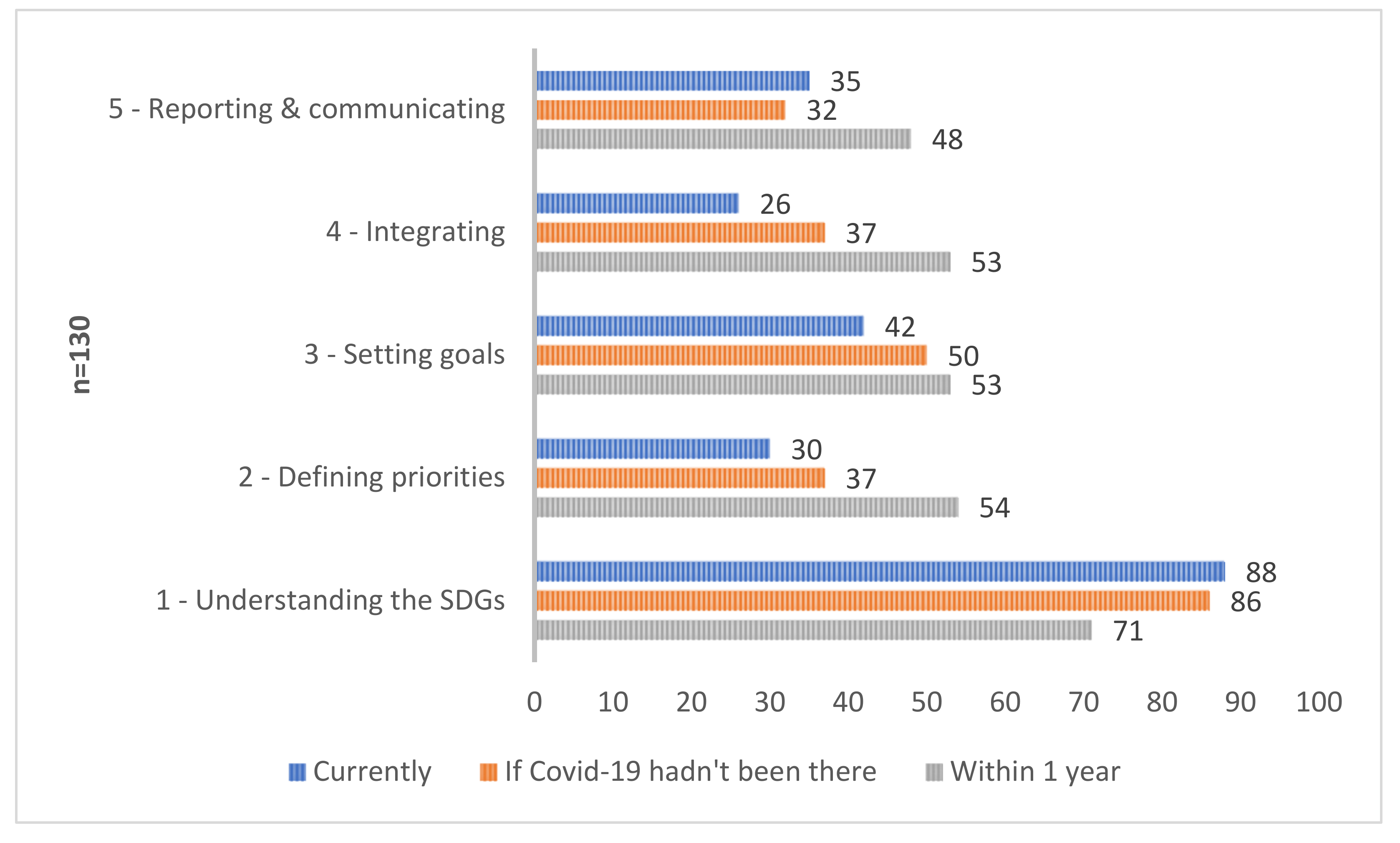

5.3. The Postponement Effect

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pradhan, P.; Subedi, D.R.; Khatiwada, D.; Joshi, K.K.; Kafle, S.; Chhetri, R.P.; Dhakal, S.; Gautam, A.P.; Khatiwada, P.P.; Mainaly, J. The COVID-19 pandemic not only poses challenges, but also opens opportunities for sustainable transformation. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2021EF001996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzad, F.S.; Salamzadeh, Y.; Amran, A.B.; Hafezalkotob, A. Social Innovation: Towards a better life after COVID-19 crisis: What to concentrate on. J. Entrep. Bus. Econ. 2020, 8, 89–120. [Google Scholar]

- Martinoli, S. 2030 Agenda and Business Strategies: The Sustainable Development Goals as a Compass towards a Common Direction; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2021; pp. 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulla, K.; Voigt, B.-F.; Cibian, S.; Scandone, G.; Martinez, E.; Nelkovski, F.; Salehi, P. Effects of COVID-19 on the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah Shayan, N.; Mohabbati-Kalejahi, N.; Alavi, S.; Zahed, M.A. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L. Public Administration and Governance for the SDGs: Navigating between Change and Stability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myer, R.A.; Moore, H.B. Crisis in context theory: An ecological model. J. Couns. Dev. 2006, 84, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, R.; Fisher, B. Reset sustainable development goals for a pandemic world. Nature 2020, 583, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottersen, O.P.; Engebretsen, E. COVID-19 puts the sustainable development goals center stage. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1672–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, J.A.; Van Tulder, R. Beyond COVID-19: Applying “SDG logics” for resilient transformations. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2020, 3, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, M.; Cheng, S.; Hou, W.; Song, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Shan, Y. County-level CO2 emissions and sequestration in China during 1997–2017. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 391. [Google Scholar]

- Le Quéré, C.; Jackson, R.B.; Jones, M.W.; Smith, A.J.; Abernethy, S.; Andrew, R.M.; De-Gol, A.J.; Willis, D.R.; Shan, Y.; Canadell, J.G. Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. What Will COVID-19 Do to the Sustainable Development Goals? 2020. Available online: https://www.undispatch.com/what-will-COVID-19-do-to-the-sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Sumner, A.; Hoy, C.; Ortiz-Juarez, E. Estimates of the Impact of COVID-19 on Global Poverty; WIDER Working Paper; The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER): Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner, A.; Ortiz-Juarez, E.; Hoy, C. Precarity and the Pandemic: COVID-19 and Poverty Incidence, Intensity, and Severity in Developing Countries. WIDER Working Paper; The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER): Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. Capitalism and Freedom; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alibegovic, M.; Cavalli, L.; Lizzi, G.; Romani, I.G.; Vergalli, S. COVID-19 & SDGs: Does the current pandemic have an impact on the 17 Sustainable Development Goals? A qualitative analysis. A Qualitative Analysis (June 8, 2020). FEEM Policy Brief. 2020. Available online: https://www.feem.it/publications/covid-19-sdgs-does-the-current-pandemic-have-an-impact-on-the-17-sustainable-development-goals-a-qualitative-analysis/ (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Hörisch, J. The relation of COVID-19 to the UN sustainable development goals: Implications for sustainability accounting, management and policy research. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 5, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M.; Nilsson, M.; Raworth, K.; Bakker, P.; Berkhout, F.; De Boer, Y.; Rockström, J.; Ludwig, K.; Kok, M. Beyond cockpit-ism: Four insights to enhance the transformative potential of the sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1651–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogge, T.; Sengupta, M. The Sustainable Development Goals: A plan for building a better world? J. Glob. Ethics 2015, 11, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.; Kanie, N. The transformative potential of the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2016, 16, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, D.A.; Sabatier, P.A. Implementation and Public Policy; Scott Foresman: Northbrook, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Fiandrino, S.; Scarpa, F.; Torelli, R. Fostering Social Impact Through Corporate Implementation of the SDGs: Transformative Mechanisms Towards Interconnectedness and Inclusiveness. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. Sustainable Development Report 2019; Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN): New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Beshi, T.D.; Kaur, R. Public trust in local government: Explaining the role of good governance practices. Public Organ. Rev. 2020, 20, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Adams-Prassl, A.; Boneva, T.; Golin, M.; Rauh, C. Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys. J. Public Econ. 2020, 189, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Living and Working in Europe 2021; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brezzi, M.; González, S.; Nguyen, D.; Prats, M. An Updated OECD Framework on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions to Meet Current and Future Challenges; OECD Working Papers on Public Governance; OECD: Paris, France, 2021; Volume 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.P.; Meng, S.; Wu, Y.-J.; Mao, Y.-P.; Ye, R.-X.; Wang, Q.-Z.; Sun, C.; Sylvia, S.; Rozelle, S.; Raat, H.; et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: A scoping review. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleetwood, J. Social justice, food loss, and the sustainable development goals in the era of COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetrapal, S.; Bhatia, R. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health system & Sustainable Development Goal 3. Indian J. Med. Res. 2020, 151, 395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Mangla, S.K.; Kazançoğlu, Y. COVID-19 impact on sustainable production and operations management. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2020, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunny, A.R.; Sazzad, S.A.; Prodhan, S.H.; Ashrafuzzaman, M.; Datta, G.C.; Sarker, A.K.; Rahman, M.; Mithun, M.H. Assessing impacts of COVID-19 on aquatic food system and small-scale fisheries in Bangladesh. Mar. Policy 2021, 126, 104422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal Filho, W.; Brandli, L.L.; Lange Salvia, A.; Rayman-Bacchus, L.; Platje, J. COVID-19 and the UN sustainable development goals: Threat to solidarity or an opportunity? Sustainability 2020, 12, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO & WFP. FAO-WFP Early Warning Analysis of Acute Food Insecurity Hotspots: July 2020; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Food Programme: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sempiga, O. Investing in Sustainable Development Goals: Opportunities for private and public institutions to solve wicked problems that characterize a VUCA world. In Investment Strategies—New Advances and Challenges; Prelipcean, G., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-83768-199-0. [Google Scholar]

- Forestier, O.; Kim, R.E. Cherry-picking the Sustainable Development Goals: Goal prioritization by national governments and implications for global governance. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIVITAS. The ‘Climate Streets’ of Antwerp. 2022. Available online: https://sump-plus.eu/news?c=search&uid=F08FBTRh (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Soberón, M.; Sánchez-Chaparro, T.; Urquijo, J.; Pereira, D. Introducing an Organizational Perspective in SDG Implementation in the Public Sector in Spain: The Case of the Former Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Food and Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K. Resilience in business and management research: A review of influential publications and a research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadida, A.L.; Tarvainen, W.; Rose, J. Organizational improvisation: A consolidating review and framework. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, A.; Janetschek, H.; Malerba, D. Translating sustainable development goal (SDG) interdependencies into policy advice. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nature Editoral. Time to revise the Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 2020, 583, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals; Report of the Secretary-General; High-level political forum on sustainable development, convened under the auspices of the Economic and Social Council: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Social Report 2020. Inequality in a Rapidly Changing World; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Ed.; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GRI; UN Global Compact; WBCSD. SDG Compass. 2015. Available online: https://sdgcompass.org/ (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones Alonso, E.; Van Ongevalle, J.; Molenaers, N.; Vandenbroucke, S. SDG Compass Guide: Practical Frameworks and Tools to Operationalise Agenda 2030; HIVA-KU Leuven Working Paper; HIVA-KU Leuven: Leuven, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaamse Overheid. SDG Handleiding Voor Overheidsorganisaties; Departement Kanselarij & Bestuur, Ed.; Vlaamse Overheid: Brussel, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grainger-Brown, J.; Malekpour, S. Implementing the sustainable development goals: A review of strategic tools and frameworks available to organisations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muff, K.; Kapalka, A.; Dyllick, T. The Gap Frame—Translating the SDGs into relevant national grand challenges for strategic business opportunities. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.L.; Zhang, S. From fighting COVID-19 pandemic to tackling sustainable development goals: An opportunity for responsible information systems research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassankhani, M.; Alidadi, M.; Sharifi, A.; Azhdari, A. Smart City and Crisis Management: Lessons for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; Loualiche, E. State and local government employment in the COVID-19 crisis. J. Public Econ. 2021, 193, 104321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, J.; Špaček, D. The COVID-19 pandemic and local government finance: Czechia and Slovakia. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2020, 32, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, I.; Humby, S.; Harwood, A. On the resilience of corporate social responsibility. Eur. Manag. J. 2011, 29, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Urbieta, L.; Boiral, O. Organizations’ engagement with sustainable development goals: From cherry-picking to SDG-washing? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Initial progress in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A review of evidence from countries. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1453–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Prioritising SDG targets: Assessing baselines, gaps and interlinkages. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranängen, H.; Cöster, M.; Isaksson, R.; Garvare, R. From global goals and planetary boundaries to public governance—A framework for prioritizing organizational sustainability activities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Standard Error Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDG Implementation Currently (A) | 2.41 | 0.851 | 0.075 |

| SDG Implementation if COVID-19 had not been there (B) | 2.65 | 0.895 | 0.079 |

| SDG Implementation within 1 year (C) | 3.06 | 1.002 | 0.088 |

| Paired-sample correlations | |||

| Correlation | Significance. | ||

| A & B | 0.828 | <0.001 | |

| Paired-samples test | |||

| Paired differences | |||

| Mean difference | t | Significance. (2-tailed) | |

| A & B | −0.246 | −5.457 | <0.001 |

| n = 130 |

| Reduced Engagement | No Change | Increased Engagement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % of Total | Number | % of Total | Number | % of Total | |

| SDG1 | 2 | 1.79% | 50 | 44.64% | 60 | 53.57% |

| SDG2 | 3 | 2.70% | 74 | 66.67% | 34 | 30.63% |

| SDG3 | 3 | 2.68% | 43 | 38.39% | 66 | 58.93% |

| SDG4 | 7 | 6.36% | 77 | 70.00% | 26 | 23.64% |

| SDG5 | 4 | 3.67% | 99 | 90.83% | 6 | 5.50% |

| SDG6 | 4 | 3.67% | 95 | 87.16% | 10 | 9.17% |

| SDG7 | 9 | 8.11% | 88 | 79.28% | 14 | 12.61% |

| SDG8 | 5 | 4.50% | 82 | 73.87% | 24 | 21.62% |

| SDG9 | 7 | 6.48% | 87 | 80.56% | 14 | 12.96% |

| SDG10 | 1 | 0.90% | 83 | 74.77% | 27 | 24.32% |

| SDG11 | 6 | 5.36% | 84 | 75.00% | 22 | 19.64% |

| SDG12 | 8 | 7.14% | 85 | 75.89% | 19 | 16.96% |

| SDG13 | 7 | 6.25% | 86 | 76.79% | 19 | 16.96% |

| SDG14 | 6 | 5.45% | 98 | 89.09% | 6 | 5.45% |

| SDG15 | 4 | 3.64% | 93 | 84.55% | 13 | 11.82% |

| SDG16 | 6 | 5.50% | 84 | 77.06% | 19 | 17.43% |

| SDG17 | 9 | 8.18% | 80 | 72.73% | 21 | 19.09% |

| Currently | If COVID-19 Had not Been There | Within 1 Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Understanding the SDGs | 88 | 67.69% | 86 | 66.15% | 71 | 54.62% |

| Defining priorities | 30 | 23.08% | 37 | 28.46% | 54 | 41.54% |

| Setting goals | 42 | 32.31% | 50 | 38.46% | 53 | 40.77% |

| Integrating | 26 | 20.00% | 37 | 28.46% | 53 | 40.77% |

| Reporting & communicating | 35 | 26.92% | 32 | 24.62% | 48 | 36.92% |

| Total responses | 221 | n = 130 | 242 | n = 130 | 279 | n = 130 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mestdagh, B.; Sempiga, O.; Van Liedekerke, L. The Impact of External Shocks on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Linking the COVID-19 Pandemic to SDG Implementation at the Local Government Level. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076234

Mestdagh B, Sempiga O, Van Liedekerke L. The Impact of External Shocks on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Linking the COVID-19 Pandemic to SDG Implementation at the Local Government Level. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):6234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076234

Chicago/Turabian StyleMestdagh, Björn, Olivier Sempiga, and Luc Van Liedekerke. 2023. "The Impact of External Shocks on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Linking the COVID-19 Pandemic to SDG Implementation at the Local Government Level" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 6234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076234

APA StyleMestdagh, B., Sempiga, O., & Van Liedekerke, L. (2023). The Impact of External Shocks on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Linking the COVID-19 Pandemic to SDG Implementation at the Local Government Level. Sustainability, 15(7), 6234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076234