Uses and Functions of the Territorial Brand over Time: Interdisciplinary Cultural-Historical Mapping

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Place Brand and Place Branding Concepts

2.2. Territorial Brand and the Territory

3. Research Methodology

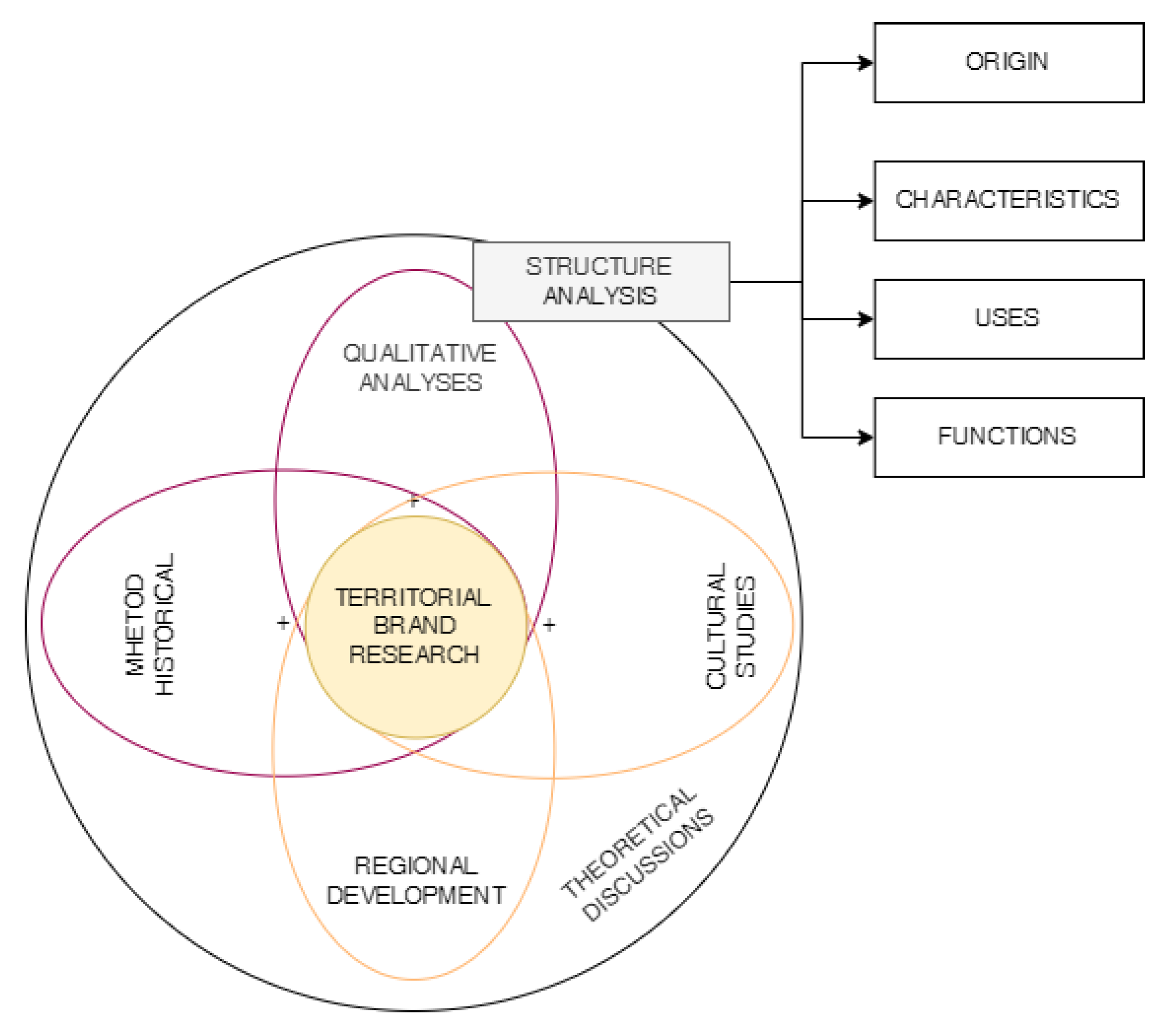

3.1. Method

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Study Variables

- Does the territorial brand have different characteristics over time?

- Has the use of the territorial brand always been (and is it still) economic in nature?

- What is the function of the territorial brand?

- What discourses are involved in the territorial brand?

- Does the origin of the territorial brand influence its characteristics, uses, functions and discourses over centuries?

3.5. Research Period

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of the Territorial Brand

4.2. Use of the Territorial Brand

4.3. Function of the Territorial Brand

4.4. Territorial Brand Speeches

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Research Limitations

5.4. Final Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anholt, S. Nation brands of the twenty-first century. J. Brand Manag. 1998, 5, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, J.S.E.; Portet Ginesta, X.; Algado, S.S. De la marca comercial a la marca de território: Los casos de la doc priorat y do Montsant [From the trademark to the territorial brand: The cases of the doc priorat and do Montsant]. Hist. Comun. Soc. 2013, 19, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G. The Instruments of Place Branding: How is it Done? Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2009, 16, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almeida, G.G.F. Marca Territorial Como Produto Cultural no Âmbito do Desenvolvimento Regional: O Caso de Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. Territorial Brand as a Cultural Product within the Scope of Regional Development: The Case of Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Santa Cruz do Sul, Santa Cruz do Sul, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, G.G.F.; Cardoso, L. Discussions between Place Branding and Territorial Brand in Regional Development-A Classification Model Proposal for a Territorial Brand. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M. A natureza do espaço: Técnica e tempo, razão e emoção. In The Nature of Space: Technique and Time, Reason, and Emotion; Hucitec: São Paulo, Brazil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Anholt, S. Definitions of place branding–Working towards a resolution. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2010, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aitken, R.; Campelo, A. The four Rs of place branding. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, K.; Insch, A. The strategic importance of brand positioning in the place brand concept: Elements, structure, and application capabilities. J. Int. Stud. 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Merunka, D. The Use of Territory of Origin as a Branding Tool. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2014, 34, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Haider, D.; Rein, I. Marketing Places; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D. Criando e administrando marcas de sucesso. In Creating and Managing Successful Brands; Futura: São Paulo, Brazil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gobé, M. A emoção das marcas: Conectando marcas às pessoas. In The Emotion of Brands: Connecting Brands to People; Campus: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, D.B. Como as marcas se tornam ícones: Os princípios do branding cultural. In How Brands Become Icons: The Principles of Cultural Branding; Cultrix: São Paulo, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, B.; Phau, I. Conceptualizing attitudes towards brand genuinely: Scale development and validation. J. Brand Manag. 2022, 29, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.G.; Tseng, T.H. On the relationships among brand experience, hedonic emotions, and brand equity. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 994–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M. Analysing the complex relationship between logo and brand. Place Brand Public Dipl. 2017, 13, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D. Marcas: Brand equity gerenciando o valor da marca. In Brands: Brand Equity Managing Brand Value; Negócio: São Paulo, Brazil, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, S.; Chartrand, T.L.; Fitzsimons, G.J. When brands reflect our ideal world: The values and brand preferences of consumers who support versus reject society’s dominant ideology. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 42, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brïdson, K.; Evans, J. The secret to a fashion advantage is brand orientation. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2004, 32, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baxter, J.; Kerr, G.; Clarke, R.J. Brand orientation and the voices from within. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 1079–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veljković, S.; Kaličanin, D. Improving business performance through brand management practice. Econ. Ann. 2016, 61, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazimi, S. Sense of Place and Place Identity. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. 2014, 1, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reitsamer, B.F.; Brunner-Sperdin, A. It’s all about the brand: Place brand credibility, place attachment, and consumer loyalty. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.C.; Ordanini, A.; Giambastiani, G. The Concept of Authenticity: What It Means to Consumers. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D. Managing Brand Equity—Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis, M. Place branding: A review of trends and conceptual models. Mark. Rev. 2005, 5, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medway, D.; Warnaby, G. What’s in a name? Place branding and toponymic commodification. Environ. Plan. A 2014, 46, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedeliento, G.; Kavaratzis, M. Bridging the gap between culture, identity, and image: A structurationist conceptualization of place brands and place branding. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Florek, M. Place brands: Why, who, what, when, where, and how? In Marketing Countries, Places, and Place-Associated Brands; Papadopoulos, N., Cleveland, M., Eds.; Elgaronline: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mariutti, F.G.; Giraldi, J.D.M.E. Branding cities, regions, and countries: The roadmap of place brand equity. RAUSP Manag. J. 2021, 56, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assche, K.V.; Beunen, R.; Oliveira, E. Spatial planning, and place branding: Rethinking relations and synergies. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1274–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greeni, S.; Horlings, L.G.; Soini, K. Linking spatial planning and place branding strategies through cultural narratives in places. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1355–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wachsmuth, D.; Kilfoil, P. Two logics of regionalism: The development of a regional imaginary in the Toronto–Waterloo Innovation Corridor. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntounis, N.; Kavaratzis, M. Re-branding the High Street: The place branding process and reflections from three U.K. towns. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Govers, R. From place marketing to place branding and back. Place Brand Public Dipl. 2011, 7, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charters, S.; Spielmann, N. Characteristics of strong territorial brands: The case of champagne. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Mitchell, R.; Ménival, D. The territorial brand in wine. In Proceedings of the 6th AWBR International Conference, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Donner, M.I.M. Understanding Place Brands as Collective and Territorial Development Processes. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melewar, T.C.; Skinner, H. Territorial brand management: Beer, authenticity, and sense of place. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 116, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, O.V.; Karachyna, N.P.; Vakar, T.V.; Vitiuk, A.V. Territorial Branding as an Instrument for Competitiveness of Rural Development. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2020, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, G.G.F.; Rezende, D.A. Marca Territorial e Subprojetos de Cidade Digital Estratégica Como Recursos Urbanos Contemporâneos: O Caso de Porto, Portugal; Análise Social: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 284–306. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, G.G.F. Estratégias das marcas territoriais na representação e reputação dos territórios no âmbito do desenvolvimento regional [Territorial brand strategies in the representation and reputation of territories in the context of regional development]. EURE Rev. Latinoam. Estud. Urbano Reg. 2023, 49, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Paasi, A. Bounded spaces in a ‘borderless world’? Border studies, power, and the anatomy of the territory. J. Power 2009, 2, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A.; Ferdoush, M.A.; Jones, R.; Murphy, A.B.; Agnew, J.; Ochoa Espejo, P.; Fall, J.J. Locating the territoriality of territory in border studies. Political Geogr. 2022, 95, 102584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syssner, J. Place branding from a multi-level perspective. Place Brand Public Dipl. 2010, 6, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankinson, G. Relational network brands: Towards a conceptual model of place brands. J. Vacat. Mark. 2004, 10, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffestin, C. Por uma geografia do poder. In By a Geography of Power; Ática: São Paulo, Brazil, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pecquer, B. O desenvolvimento territorial: Uma nova abordagem dos processos de desenvolvimento para as economias do sul. Raízes 2005, 24, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- De Andrés Pizarro, J. El análisis de estudios cualitativo. Atención Primaria 2000, 25, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thayer, A.; Evans, M.A.; Mcbride, A.; Queen, M.; Spyridakis, J.H. Content Analysis as a Best Practice in Technical Communication Research. J. Tech. Writ. Commun. 2007, 37, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggarty, L. What is content analysis? Med. Teach. 2009, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbia, J.M. Diseño, muestreo y análisis en la investigación cualitativa. Hologramática 2007, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, L.; Araújo Vila, N.; Soliman, M.; Araújo, S.F.; Almeida, G.G.F. How to Employ Zipf’s Laws for Content Analysis in Tourism Studies? Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2022, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, B.; Knapp, T. Dictionary of Nursing Theory and Research, 3rd ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psych. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cardoso, L.; Dias, F.; Araújo, A.F.; Marques, M.I.A. A destination imagery processing model: Structural differences between dream and favourite destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyngäs, H.; Kaakinen, P. Deductive Content Analysis. In The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research; Kyngäs, H., Mikkonen, K., Kääriäinen, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golder, P.N. Historical Method in Marketing Research with New Evidence on Long-Term Market Share Stability. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.F.; Thomson, A.R. Management in Historical Perspective: Stages and Paradigms. Compet. Chang. 2006, 10, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, D.M. What is the Socio-Historical Method in the Study of Religion? Socio-Hist. Exam. Relig. Minist. 2020, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rede, M. A Bíblia Pode ser Considerada um Documento Histórico? Journal da USP. 2021. Available online: https://jornal.usp.br/artigos/a-biblia-pode-ser-considerada-um-documento-historico/ (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Strategy-Box. Site Institucional Sobre as Marcas. [Série] Como as Marcas Surgiram e o que isso tem a ver com Branding (s.d.). Available online: https://strategy-box.com/blog/2021/5/19/como-as-marcas-surgiram-e-o-que-isso-tem-a-ver-com-branding (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Brand Target. Origem e Evolução Do Branding [Origin and Evolution of Branding]. (s.d). Available online: https://brandtarget.wordpress.com/2015/09/12/origem-e-evolucao-do-branding/ (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Ideia de Marketing. A História da Marca: Um Fenômeno em Evolução [The Brand Story: An Evolving Phenomenon] (s.d.). Available online: https://www.ideiademarketing.com.br/2017/01/18/historia-da-marca-um-fenomeno-em-evolucao/ (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Govers, R.; Go, F.M. Place Branding: Glocal, Virtual and Physical, Identities Constructed, Imagined, and Experienced; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J.D. Image as a factor in tourism development. J. Travel Res. 1975, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpiano, R.; González, C. You are here. Revista 180 2009, 23, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosino, C. Monstration of the contemporary city: The example of Hoxton in London and the Young British Artists movement in the 1990s. Trav. L’institut Geogr. Reims 2007, 33, 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.C. The contribution of regional shopping centres to local economic development: Threat or opportunity? Area 1992, 24, 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- Savona, P. The problem of cities: Less aesthetics, more ethics. Rev. Econ. Cond. Italy 1992, 1, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fachin, O. Fundamentos de Metodologia, 5th ed.; Saraiva: São Paulo, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes, A.C. Narrative analysis: Exploring the whats and hows of personal stories. Qual. Res. Health Care 2015, 1, 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnesorge, H.W. The method of comparative-historical analysis: A tailor-made approach to public diplomacy research. Place Brand Public Dipl. 2022, 18, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo Júnior, E.M. Consumo de Experiência Turístico-Religiosa na Construção de Territorialidades na Terra Santa [Consumption of Tourist-Religious Experience in the Construction of Territorialities in the Holy Land]. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Santa Cruz do Sul, Santa Cruz do Sul, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli, C. Branding as urban collective strategy-making: The formation of Newcastle Gateshead’s organizational identity. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Website | Link |

|---|---|

| Strategy-Box | https://strategy-box.com/blog/2021/5/19/como-as-marcas-surgiram-e-o-que-isso-tem-a-ver-com-branding (accessed on 3 March 2022). |

| Brand Target | https://brandtarget.wordpress.com/2015/09/12/origem-e-evolucao-do-branding/ (accessed on on 3 March 2022). |

| Ideia de Marketing | https://www.ideiademarketing.com.br/2017/01/18/historia-da-marca-um-fenomeno-em-evolucao/ (accessed on on 3 March 2022). |

| Terms | Scopus (Period) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Territorial brand | 75 (2007–2022) | 0.5% |

| Territorial branding | 46 (2009–2022) | 0.3% |

| Place branding | 1039 (2001–2022) | 67% |

| Place brand | 396 (2004–2022) | 25% |

| Others | (2001–2022) | 7.2% |

| Total terms | 1556 (2001–2022) | 100% |

| Origin Century | Characteristics | Use | Function | Speeches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XXI | Territorial brands investigated from different perspectives. | Use in tourism | Generate economic development | A feeling of global belonging |

| XX | The first country coined its territorial brand due to an economic crisis. Afterward, other countries also created their territorial brands | Use in tourism | Be on a global map of places | Feeling of competition Need for competition between territories on different scales (local, regional, national, etc.) |

| XIX | The emblems called official coats of arms appeared, referring to countries, states and municipalities that do not meet the heraldic rules but keep the nomenclature coats of arms | As the official symbol of municipalities and countries | Identify the countries, states and municipalities, regardless of the current government. | Feeling of patriotism |

| The concern with brands led to the Trademark Law in England (1862), the Federal Trademark Law in the USA (1870) and the Law for the Protection of Trademarks in Germany | Use in product quality assurance | Ensure product quality | A feeling of ownership. | |

| XVIII | In Europe, heraldic coats of arms began to lose some of their importance within society, referring to the loss of recognition of families, clans, or territories | Territorial identification sign | Identify family territories and terroir | A feeling of belonging to a social group |

| XVII | The first use of the term brand | Use of the term brand in specialized literature | Identify the owner of the territories | A feeling of ownership of something, especially property (land) |

| XVI | The terms smart city, digital city and others appear | Use of the terms smart city, digital city, sustainable city and others linked to different geographical scales | Associate personified adjectives to territorial brands: smart, digital, sustainable and other | A feeling of closeness to the territory |

| XV | Association of the term brand to cattle marking | Use in cities, states and countries | “Branding” cities with generic adjectives | Sense of ownership |

| XIV | Family coats of arms or family shields, according to heraldic rules | Use in coats of arms or family shields | Identify the families and their properties | Feeling of family |

| XIII | No evidence | *** | *** | *** |

| XII | Creation of the first official flag of a country (Denmark) in the world | Use of identity markers on national symbols | Identify a nation | Feeling of patriotism |

| XI | The brand signified the link between the manufacturer and the buyer | Use of individual brands in the business sense | Identify producers | Sense of ownership |

| X | Start of the Crusades | Use in battles and on properties | Identify clan properties and the enemies in a battle | Sense of ownership |

| VIII–IX | No evidence | *** | *** | *** |

| V–VII | Association of the sacred with the territories | Use in specific territories | Identify the territories considered “holy” | Feeling of religion |

| Previous to VI | Biblical narratives | Differentiate sacred territories from profane territories | Identify the territories considered “holy” | Feeling of closeness to the sacred |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almeida, G.G.F.d.; Almeida, P.; Cardoso, L.; Lima Santos, L. Uses and Functions of the Territorial Brand over Time: Interdisciplinary Cultural-Historical Mapping. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086448

Almeida GGFd, Almeida P, Cardoso L, Lima Santos L. Uses and Functions of the Territorial Brand over Time: Interdisciplinary Cultural-Historical Mapping. Sustainability. 2023; 15(8):6448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086448

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmeida, Giovana Goretti Feijó de, Paulo Almeida, Lucília Cardoso, and Luís Lima Santos. 2023. "Uses and Functions of the Territorial Brand over Time: Interdisciplinary Cultural-Historical Mapping" Sustainability 15, no. 8: 6448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086448