Assistance Needed for Increasing Knowledge of HACCP Food Safety Principles for Organic Sector in Selected EU Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Survey

2.2. Description of the Questionnaire

2.3. Characteristics of the Surveyed Operators

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Knowledge of the HACCP Concept

3.2. The Application of a Functional Self-Control System Based on the HACCP Principles

3.3. Participation in Food Hygiene/Safety Training

3.4. The Areas Where Organic Food Operators Need Assistance

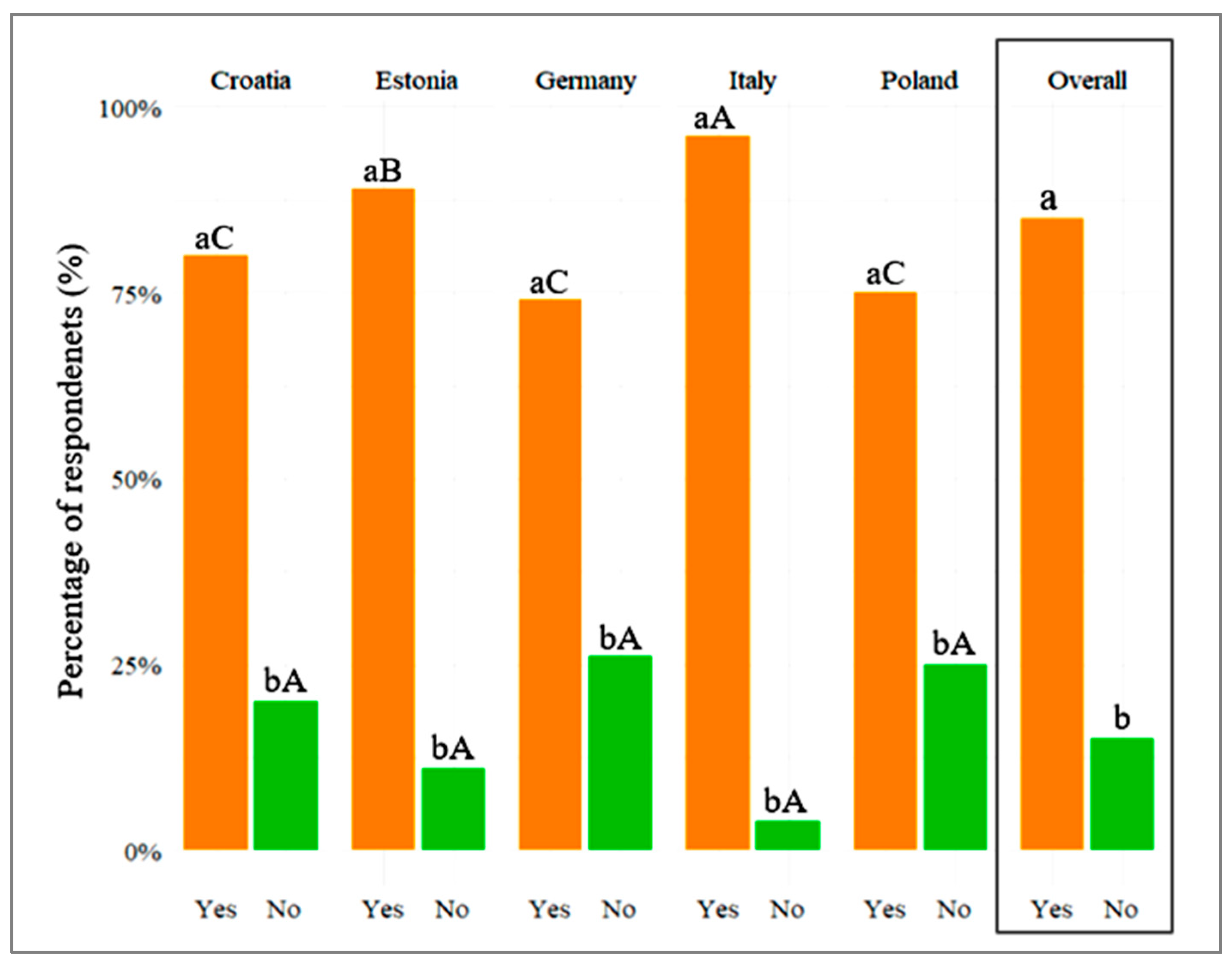

3.5. The Need for Assistance concerning HACCP Principles

3.6. Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hueston, W.; McLeod, A. Overview of the global food system: Changes over time/space and lessons for future food safety. In Improving Food Safety through a One Health Approach: Workshop Summary; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 Laying Down the General Principles and Requirements of Food Law, Establishing the European Food Safety Authority and Laying Down Procedures in Matters of Food Safety. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/eu-exit/https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02002R0178-20190 (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EC) No 852/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004. On the Hygiene of Foodstuffs. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2004/852/oj (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 on Microbiological Criteria for Foodstuffs. UNEP Law and Environment Assistance Platform. Available online: https://leap.unep.org/countries/eu/national-legislation/commission-regulation-ec-no-20732005-microbiological-criteria (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization. Codex Alimentarius. General Principles of Food Hygiene. CXC 1-1969. Adopted in 1969. Amended in 1999. Revised in 1997, 2003, 2020. Editorial Corrections in 2011. 1969. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXC%2B1-1969%252FCXC_001e.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EC) No 2018/848 of the European parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on organic production and labelling of organic products and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007. Off. J. Eur. Union L 2018, 150, 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Soroka, A.; Mazurek-Kusiak, A.K.; Trafialek, J. Organic food in the diet of residents of the visegrad group (V4) countries—Reasons for and barriers to its purchasing. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, H.; Schlatter, B.; Trávníček, J. Organic Farming and Market Development in Europe and the European Union. In The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2023; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL and IFOAM-Organics International, Frick and Bonn; Available online: https://www.fibl.org/en/shop-en/1254-organic-world-2023 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- European Commission (EC). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; COM/2020/381 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki, R.; Biczkowski, M.; Wiśniewski, Ł.; Wiśniewski, P.; Bielski, S.; Marks-Bielska, R. Towards Green Agriculture and Sustainable Development: Pro-Environmental Activity of Farms under the Common Agricultural Policy. Energies 2023, 16, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barański, M.; Volakakis, N.; Seal, C.; Sanderson, R.; Stewart, G.B.; Benbrook, C.; Biavati, B.; Markellou, E.; Giotis, C.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J.; et al. Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: A systematic literature review and meta-analyses. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 794–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rempelos, L.; Wang, J.; Barański, M.; Watson, A.; Volakakis, N.; Hoppe, H.W.; Kühn-Velten, W.N.; Hadall, C.; Hasanaliyeva, G.; Chatzidimitriou, E.; et al. Diet and food type affect urinary pesticide residue excretion profiles in healthy individuals: Results of a randomized controlled dietary intervention trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Średnicka-Tober, D.; Barański, M.; Seal, C.; Sanderson, R.; Benbrook, C.; Steinshamn, H.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J.; Rembiałkowska, E.; Skwarło-Sońta, K.; Eyre, M.; et al. Composition differences between organic and conventional meat: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 994–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Średnicka-Tober, D.; Barański, M.; Seal, C.J.; Sanderson, R.; Benbrook, C.; Steinshamn, H.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J.; Rembiałkowska, E.; Skwarło-Sońta, K.; Eyre, M.; et al. Higher PUFA and n-3 PUFA, conjugated linoleic acid, α-tocopherol and iron, but lower iodine and selenium concentrations in organic milk: A systematic literature review and meta- and redundancy analyses. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1043–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Migliorini, P.; Wezel, A. Converging and diverging principles and practices of organic agriculture regulations and agroecology. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 37, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costantini, E.; La Torre, A. Regulatory framework in the European Union governing the use of basic substances in conventional and organic production. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2022, 129, 715–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudsepp, P.; Koskar, J.; Anton, D.; Meremäe, K.; Kapp, K.; Laurson, P.; Bleive, U.; Kaldmäe, H.; Roasto, M.; Püssa, T. Antibacterial and antioxidative properties of different parts of garden rhubarb, blackcurrant, chokeberry and blue honeysuckle. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 2311–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, R.R.; Zakhour, C.M.; Gould, L.H. Foodborne Disease Outbreaks Associated with Organic Foods in the United States. J. Food Prot. 2016, 79, 1953–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trafialek, J.; Kolozyn-Krajewska, D. Implementation of safety assurance system in food production in Poland. Polish J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2011, 61, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotsanopoulos, K.V.; Arvanitoyannis, I.S. Audit results of UK meat companies—Critical analysis. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2684–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, N.T.; Rhamadani, A.; Wisnel, W. Designing food safety standards in beef jerky pro-duction process with the application of hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP). Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 50, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowska-Gawlik, K.; Kolanowski, W.; Trafialek, J. Evaluating suppliers of spices, casings and packaging to a meat processing plant using food safety audits data gathered during a 13-year period. Food Control 2021, 127, 108138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafiałek, J.; Lehrke, M.; Lücke, F.-K.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Janssen, J. HACCP-based procedures in Germany and Poland. Food Control 2015, 55, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akash, H.; Arrah, A.A.; Bhatti, F.; Maabreh, R.; Arrah, R.A. The effect of food safety training program on food safety knowledge and practices in hotels’ and hospitals’ food services. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2022, 11, 9914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafialek, J.; Drosinos, E.H.; Laskowski, W.; Jakubowska-Gawlik, K.; Tzamalis, P.; Leksawasdi, N.; Surawang, S.; Kolanowski, W. Street food vendors’ hygienic practices in some Asian and EU countries—A survey. Food Control 2018, 85, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Santiago, J.; García, A.I.G.; Gómez-Villarino, M.T. An Evaluation of Food Safety Performance in Wineries. Foods 2022, 11, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atambayeva, Z.; Nurgazezova, A.; Rebezov, M.; Kazhibayeva, G.; Kassymov, S.; Sviderskaya, D.; Toleubekova, S.; Assirzhanova, Z.; Ashakayeva, R.; Apsalikova, Z. A Risk and Hazard Analysis Model for the Production Process of a New Meat Product Blended With Germinated Green Buckwheat and Food Safety Awareness. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 902760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolanowski, W.; Trafialek, J.; Drosinos, E.H.; Tzamalis, P. Polish and Greek young adults’ experience of low quality meals when eating out. Food Control 2020, 109, 106901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, M. Testing and Plotting Procedures for Biostatistics. In Package ‘RVAideMemoire’; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2018; Available online: https://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/RVAideMemoire/index.html (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Rennes, A.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. JSS J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Herath, D.; Henson, S. Barriers to HACCP implementation: Evidence from the food processing sector in Ontario, Canada. Agribusiness 2010, 26, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, A.D.; Cobanoglu, F.; Tunalioglu, R.; Ova, G. Barriers and benefits of the implementation of food safety management systems among the Turkish dairy industry: A case study. Food Control 2012, 25, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garayoa, R.; Díez-Leturia, M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; García-Jalón, I.; Vitas, A.I. Catering services and HACCP: Temperature assessment and surface hygiene control before and after audits and a specific training session. Food Control 2014, 43, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusato, S.; Gameiro, A.H.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Corassin, C.H.; Cruz, A.G.; de Oliveira, C.A.F. Assessing the costs involved in the implementation of GMP and HACCP in a small dairy factory. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2014, 6, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shabib, N.A.; Mosilhey, S.H.; Husain, F.M. Cross-sectional study on food safety knowledge, attitude and practices of male food handlers employed in restaurants of King Saud University, Saudi Arabia. Food Control 2016, 59, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek-Kusiak, A.; Sawicki, B.; Kobyłka, A. Contemporary Challenges to the Organic Farming: A Polish and Hungarian Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramov, N.; Slavuj, L. Ekološka poljoprivreda u Hrvatskoj—Analiza razvoja i stavovi mladih o ekološkim poljoprivrednim proizvodima. Geogr. Horiz. 2021, 67, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ministarstvo Poljoprivrede—Statistika. Available online: https://poljoprivreda.gov.hr/statistika-360/360 (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- European Commission (EC). Commission Notice on the implementation of food safety management systems covering prerequisite programs (PRPs) and procedures based on the HACCP principles, including the facilitation/flexibility of the implementation in certain food businesses. Off. J. Eur. Union L 2016, 278, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of HACCP plans in standardized food safety management systems—The case of small-sized Polish food businesses. Food Control 2019, 106, 106716. [CrossRef]

- Huq, A.O.; Uddin, M.J.; Haque, K.F.; Roy, P.; Hossain, M.B. Health, hygiene practices and safety measures of selected baking factories in Tangail region, Bangladesh. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2013, 2, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Jubayer, M.F.; Kayshar, M.S.; Hossain, M.S.; Uddin, M.N.; Al-Emran, M.; Akter, S.S. Evaluation of food safety knowledge, attitude, and self-reported practices of trained and newly recruited untrained workers of two baking industries in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, L.; Vallaster, L.; Wilcott, L.; Henderson, S.B.; Kosatsky, T. Evaluation of food safety knowledge, attitudes and self-reported hand washing practices in FOODSAFE trained and untrained food handlers in British Columbia, Canada. Food Control 2013, 30, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafiałek, J.; Pawłowska, J. Effect of Analysis of training provided to employess in catering company with implemented food safety management system pursuant to ISO standard of 2200 series. Food Sci. Technol. Qual. 2013, 1, 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Taha, S.; Osaili, T.M.; Saddal, N.K.; Al-Nabulsi, A.A.; Ayyash, M.M.; Obaid, R.S. Food safety knowledge among food handlers in food service establishments in United Arab Emirates. Food Control 2020, 110, 106968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kandari, D.; Al-abdeen, J.; Sidhu, J. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers in restaurants in Kuwait. Food Control 2019, 103, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetemaa, A.; Mikk, M.; Peetsmann, E. Mahepõllumajandus Eestis 2021. In Organic Farming in Estonia in 2021; The Estonian University of Life Sciences: Tartu, Estonia, 2022; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Roasto, M.; Laikoja, K. Toidu Säilimisaja Määramine (Determination of the Shelf Life of Food); Estonian University of Life Sciences: Tartu, Estonia, 2019; p. 44. ISBN 978-9949-698-73-8. [Google Scholar]

- Roasto, M. Olulised Toidupatogeenid (Essential Foodborne Pathogens); Estonian University of Life Sciences, Vali Press OÜ: Tartu, Estonia, 2019; p. 23. ISBN 978-9949-629-96-1. [Google Scholar]

- Püssa, T. Toidu Keemilised Ohud (Chemical Hazards in Food); Estonian University of Life Sciences: Tartu, Estonia, 2020; p. 24. ISBN 978-9949-698-37-0. [Google Scholar]

- Roasto, M. Biokirmed Toidutootmise Keskkonnas (Biofilms in Food Production Environment); Estonian University of Life Sciences: Tartu, Estonia, 2021; p. 21. ISBN 978-9916-669-14-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mäesaar, M.; Roasto, M. Patogeeni(de) Algallikate Väljaselgitamine Toidukäitlemise Ettevõttes (Root Cause Analyses of a Pathogen Contamination); Estonian University of Life Sciences: Tartu, Estonia, 2022; p. 28. ISBN 978-9916-669-85-3. [Google Scholar]

- Croatian Institute of Public Health, Hygiene Minimum. 2022. Available online: https://www.hzjz.hr/sluzba-zdravstvena-ekologija/higijenski-minimum/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Stanley, R.; Knight, C.; Bodnar, F. Experiences and challenges in the development of an organic HACCP system. NJAS—Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2011, 58, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cerf, O.; Donnat, E. Application of hazard analysis—Critical control point (HACCP) principles to primary production: What is feasible and desirable? Food Control 2011, 22, 1839–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number (n) and Percentage (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Answers | Croatia (n = 50) | Estonia (n = 75) | Germany (n = 42) | Italy (n = 97) | Poland (n = 52) | Overall (n = 316) |

| 1. What type of farm do you represent? | 1. Exclusive food producer | 24aB (48) | 3bC (4) | 14bB (33) | 42aA (43) | 18bB (35) | 101b (32) |

| 2. Exclusive food processor or food processor and producer | 26aB (52) | 72aA (96) | 28aB (67) | 55aA (57) | 34aB (65) | 215a (68) | |

| 2. What is the size of your farm? | 1. Small family farm (only 1–2 employees) | 40aA (80) | 38aA (51) | 22aB (52) | 54aA (56) | 21aB (40) | 175a (55) |

| 2. Large family farm (3–5 employees) | 4bB (8) | 13bA (17) | 10bAB (24) | 11bAB (11) | 16aA (31) | 54b (17) | |

| 3. Micro (6–9 employees) | 4b (8) | 8bc (11) | 5c (12) | 9bA (9) | 11a (21) | 37bc (12) | |

| 4. Small (10–49 employees) | 2bB (4) | 12bA (16) | 4cB (10) | 13b (13) | 3bB (6) | 34c (11) | |

| 5. Medium (50–249 employees) | 0b (0) | 4c (5) | 1c (2) | 8b (8) | 0b (0) | 13d (4) | |

| 6. Large (>250 employees) | 0b (0) | 0c (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 1b (2) | 3e (1) | |

| 3. Are you a certified organic producer/processor? | 1. Yes | 43aB (86) | 67aA (90) | 37aB (88) | 84aA (87) | 29aB (56) | 260a (82) |

| 2. No | 3bB (6) | 1bB (1) | 2bB (5) | 3bB (3) | 13bA (25) | 22b (7) | |

| 3. Partly certified (certain products, certain production lines) | 2b (4) | 7b (9) | 3b (7) | 10b (10) | 4c (8) | 26b (8) | |

| 4. Certifying process is ongoing | 2b (4) | 0b (0) | 0b (0) | 0b (0) | 6bc (11) | 8c (3) | |

| 4. What kind of products do you process? | 1. Fruits, berries or/and products thereof | 39aA (78) | 29aAB (39) | 13abC (31) | 20abBC (21) | 31aAB (60) | 132a (42) |

| 2. Vegetables or/and products thereof | 27aA (54) | 12bBC (16) | 6bcC (14) | 13bcBC (13) | 23aAB (44) | 81b (26) | |

| 3. Cereal grains or/and products thereof | 5bC (10) | 18abAB (24) | 15abB (36) | 30abA (31) | 10bBC (19) | 78b (25) | |

| 4. Bakery products | 0b (0) | 6bc (8) | 4bc (10) | 8cd (8) | 3c (6) | 21d (7) | |

| 5. Herbs and spices or/and products thereof | 3bC (6) | 14bA (19) | 4bcBC (10) | 11bcAB (11) | 11bAB (21) | 43c (14) | |

| 6. Oil cultures and products thereof | 10bB (20) | 6bcBC (8) | 2cC (5) | 40aA (41) | 1cC (2) | 59bc (19) | |

| 7. Meat of large farm animals (cattle, buffalo, pig, sheep, goat) | 4b (8) | 9bc (12) | 16a (38) | 10bc (10) | 10b (19) | 49c (16) | |

| 8. Meat of small farm/livestock animals (rabbit, hare, rodent) | 0b (0) | 0c (0) | 1c (2) | 2c (2) | 1c (2) | 4e (1) | |

| 9. Poultry meat (chicken, duck, turkey, quail) | 0b (0) | 4c (5) | 10ab (24) | 2c (2) | 7bc (13) | 23d (7) | |

| 10. Milk and dairy products | 3bB (6) | 11bA (15) | 13abA (31) | 12bcA (12) | 2cB (4) | 41c (13) | |

| 11. Fish and fishery products | 0b (0) | 2c (3) | 1c (2) | 4cd (4) | 0c (0) | 7e (2) | |

| Question | Answers | Number (n) and Percentage (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croatia | Estonia | Germany | Italy | Poland | Overall | ||

| Please select the areas where you need more assistance | 1. General food hygiene and safety principles | 8(16) B | 9(12) B | 15(36) B | 28(29) A | 17(33) AB | 77(24) |

| 2. Prerequisite programs (PRP) specific for organic food production/processing | 19(38) A | 22(29) A | 15(36) A | 5(5) B | 13(25) AB | 74(23) | |

| 3. Food fraud | 3(6) B | 16(21) A | 5(12) B | 21(22) A | 14(27) A | 59(19) | |

| 4. Process contaminants (e.g., acrylamide, PAHs) and residues (e.g., pesticides, medicinal) | 4(8) D | 12(16) BC | 6(14) CD | 31(32) A | 15(29) B | 68(22) | |

| 5. Food additives and other ingredients allowed in organic processing | 7(14) C | 44(59) A | 8(19) C | 19(20) B | 18(35) B | 96(30) | |

| 6. Prevention of cross-contamination and cross contact including food allergen management | 3(6) B | 10(13) AB | 8(19) AB | 14(14) A | 12(23) A | 47(15) | |

| 7. Temperature control and assurance of the cold chain | 3(6) | 7(9) | 9(21) | 7(7) | 5(10) | 31(10) | |

| 8. Drinking water quality | 2(4) B | 9(12) A | 2(5) B | 12(12) A | 0(0) B | 25(8) | |

| 9. Wrapping, packaging; requirements of Food Contact Materials (FCM) | 11(22) B | 20(27) AB | 19(45) AB | 26(27) A | 14(27) AB | 90(28) | |

| 10. Transport and vehicles | 1(2) B | 6(8) AB | 8(19) A | 12(12) A | 6(12) AB | 33(10) | |

| 11. Waste management | 4(8) B | 8(11) AB | 3(7) B | 14(14) A | 12(23) A | 41(13) | |

| 12. Pest control | 7(14) | 9(12) | 7(17) | 16(16) | 5(10) | 44(14) | |

| 13. Cleaning and disinfection | 4(8) | 9(12) | 11(26) | 16(16) | 7(13) | 47(15) | |

| 14. Staff: health, personal hygiene, training | 1(2) B | 4(5) B | 6(14) AB | 13(13) A | 4(8) B | 28(9) | |

| 15. Food safety culture | 4(8) C | 9(12) BC | 4(10) C | 20(21) A | 12(23) AB | 49(16) | |

| 16. Food ingredients including raw materials, allergens, quality requirements | 6(12) | 19(25) | 11(26) | 10(10) | 9(17) | 55(17) | |

| 17. Determination of shelf-life of food | 9(18) | 22(29) | 20(48) | 17(18) | 21(40) | 89(28) | |

| 18. Laboratory testing (production surfaces, raw materials, final products) | 10(20) B | 26(35) A | 9(21) B | 24(25) A | 11(21) B | 80(25) | |

| 19. Labelling and claims (nutritional, health) | 21(42) BC | 34(45) AB | 12(29) C | 42(43) A | 18(35) C | 127(40) | |

| 20. Traceability, recall, withdrawal of food from the market | 2(4) B | 6(8) AB | 9(21) A | 13(13) A | 14(27) A | 44(14) | |

| 21. Other | 3(6) | 3(4) | 5(12) | 7(7) | 1(2) | 19(6) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allam, M.; Bazok, R.; Bordewick-Dell, U.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Kazimierczak, R.; Laikoja, K.; Luik, A.; Fuka, M.M.; Muleo, R.; Peetsmann, E.; et al. Assistance Needed for Increasing Knowledge of HACCP Food Safety Principles for Organic Sector in Selected EU Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086605

Allam M, Bazok R, Bordewick-Dell U, Czarniecka-Skubina E, Kazimierczak R, Laikoja K, Luik A, Fuka MM, Muleo R, Peetsmann E, et al. Assistance Needed for Increasing Knowledge of HACCP Food Safety Principles for Organic Sector in Selected EU Countries. Sustainability. 2023; 15(8):6605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086605

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllam, Mohamed, Renata Bazok, Ursula Bordewick-Dell, Ewa Czarniecka-Skubina, Renata Kazimierczak, Katrin Laikoja, Anne Luik, Mirna Mrkonjić Fuka, Rosario Muleo, Elen Peetsmann, and et al. 2023. "Assistance Needed for Increasing Knowledge of HACCP Food Safety Principles for Organic Sector in Selected EU Countries" Sustainability 15, no. 8: 6605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086605