Short Commercialization Circuits and Productive Development of Agroecological Farmers in the Rural Andean Area of Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Indicators

2.4. Analysis

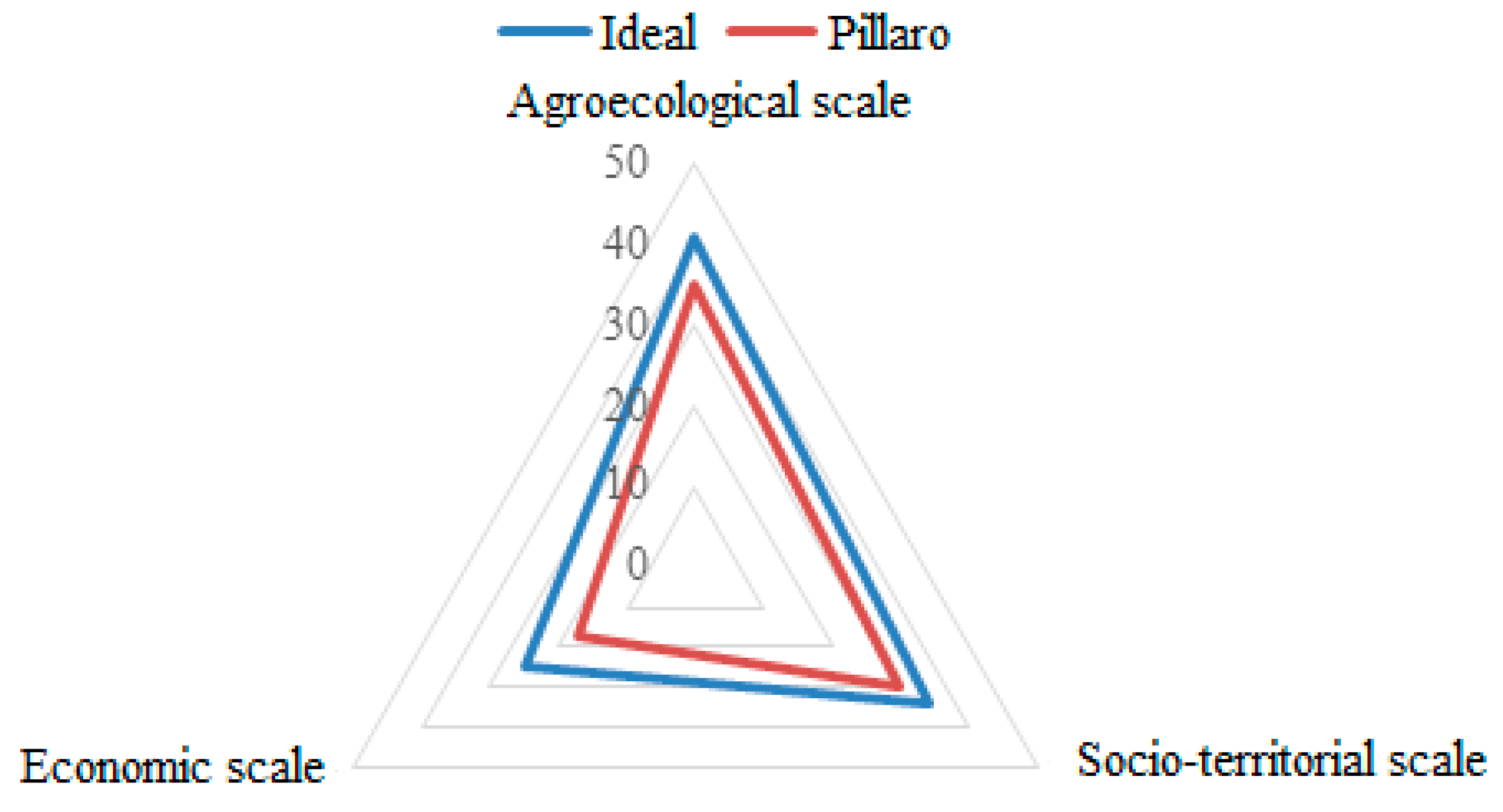

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Short Commercialization Circuits

3.2. System of Production and Commercialization of Agroecological Products

3.3. The Short Commercialization Circuit Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Molina-Murillo, S.A.; Barrientos, G.; Bonilla, M.; Garita, C.; Jiménez, A.; Madriz, M.; Paniagua, J.; Rodríguez, J.C.; Rodríguez, L.; Treviño, J.; et al. Are Agroecological Farms Resilient? Some Results Using the Tool SHARP-FAO in Costa Rica. Ingeniería 2017, 27, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FoodPrint. How Our Food System Affects Public Health. Available online: https://foodprint.org/issues/how-our-food-system-affects-public-health/ (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Selim, M.; Sabau, G. Impact of climate change on crop production and food security in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 10, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD-FAO. Agricultural Outlook 2015–2044; OECD: Paris, France, 2015; ISBN 9789264231900. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2017; ISBN 9789251095515. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, C.I.; Altieri, M.A. Bases Agroecológicas Para La Adaptación de La Agricultura al Cambio Climático. UNED Res. J. 2019, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, C.K.; Brush, S.; Costich, D.E.; Curry, H.A.; de Haan, S.; Engels, J.M.M.; Guarino, L.; Hoban, S.; Mercer, K.L.; Miller, A.J.; et al. Crop Genetic Erosion: Understanding and Responding to Loss of Crop Diversity. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 84–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán, P.; Guevara, R.; Olguín, J.; Mancilla, O. Perspectiva Campesina, Intoxicaciones Por Plaguicidas y Uso de Agroquímicos. Idesia 2016, 34, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, L.; Thapa, K.; Kanojia, N.; Sharma, N.; Singh, S.; Grewal, A.S.; Srivastav, A.L.; Kaushal, J. An Extensive Review on the Consequences of Chemical Pesticides on Human Health and Environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, A.; Nangia, A.; Prasad, M.N.V. Chapter 18—Advances in Agrochemical Remediation Using Nanoparticles. In Agrochemicals Detection, Treatment and Remediation; Prasad, M.N.V., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 465–485. ISBN 978-0-08-103017-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, A.; Sarkar, B.; Mandal, S.; Vithanage, M.; Patra, A.K.; Manna, M.C. Chapter 7—Impact of Agrochemicals on Soil Health. In Agrochemicals Detection, Treatment and Remediation; Prasad, M.N.V., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 161–187. ISBN 978-0-08-103017-2. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolopoulou-Stamati, P.; Maipas, S.; Kotampasi, C.; Stamatis, P.; Hens, L. Chemical Pesticides and Human Health: The Urgent Need for a New Concept in Agriculture. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, V.; Maslaric, M.; Bojic, S.; Jokic, M.; Mircetic, D.; Nikolicic, S. Solutions for More Sustainable Distribution in the Short Food Supply Chains. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfert, B. Community-Supported Agriculture Networks in Wales and Central Germany: Scaling Up, Out, and Deep through Local Collaboration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzuffi, C.; McKay, A.; Perge, E. The Impact of Agricultural Commercialisation on Household Welfare in Rural Vietnam. Food Policy 2020, 94, 101811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intriago, R.; Gortaire Amézcua, R.; Bravo, E.; O’Connell, C. Agroecology in Ecuador: Historical Processes, Achievements, and Challenges. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2017, 41, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A. Food Supply Chains: Coordination Governance and Other Shaping Forces. Agric. Food Econ. 2017, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evola, R.S.; Peira, G.; Varese, E.; Bonadonna, A.; Vesce, E. Short Food Supply Chains in Europe: Scientific Research Directions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esnouf, C.; Russel, M.; Bricas, N. Pour Une Alimentation Durable: Réflexion Stratégique DuALIne; Editions Quae: Versailles, France, 2011; ISBN 2-7592-1670-5. [Google Scholar]

- Carolan, M. La Sociología de La Alimentación y La Agricultura, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wezel, A.; Casagrande, M.; Celette, F.; Vian, J.F.; Ferrer, A.; Peigné, J. Agroecological Practices for Sustainable Agriculture. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme-UNEP. Global Environment Outlook Geo-6 Healthy Planet, Healthy People; UUNN: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Transforming Food and Agriculture to Achieve the SDGs: 20 Interconnected Actions to Guide Decision-Makers; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bandari, R.; Moallemi, E.A.; Lester, R.E.; Downie, D.; Bryan, B.A. Prioritising Sustainable Development Goals, Characterising Interactions, and Identifying Solutions for Local Sustainability. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 127, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change and Land: IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-00-915798-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmann, H. Why Organic Farming Is Not the Way Forward. Outlook Agric. 2019, 48, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, H.; Ali, S.; Danish, M.; Sulaiman, M.A.B.A. Factors Affecting Consumers Intentions to Purchase Dairy Products in Pakistan: A Cognitive Affective-Attitude Approach. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P. Circuitos Cortos de Comercialización alimentaria: Análisis de experiencias de la región de Valparaíso, Chile. Psicoperspect. Individuo Soc. 2020, 19, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabourin, E. Construcción social de circuitos curtos y de mercado justo: Articulación entre intercambio y reciprocidad. Theomai 2018, 38, 150–167. [Google Scholar]

- Gallar Hernández, D.; Saracho-Domínguez, H.; Rivera-Ferré, M.G.; Vara-Sánchez, I. Eating Well with Organic Food: Everyday (Non-Monetary) Strategies for a Change in Food Paradigms: Findings from Andalusia, Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaladejo, C. Análisis de la sostenibilidad de los sistemas agrícolas con el concepto de equilibración. Univ. Nac. Misiones Fac. Hum. Cienc. Soc. Secr. Investig. 1992 Rev. Estud. Reg. Posadas Secr. Investig. 1992, 31, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sievers, M.; Saarelainen, E. El Impulso del Desarrollo Rural a Través del Empleo Productivo y el Trabajo Decente: Aprovechar los 40 Años de Experiencia de la OIT en las Zonas Rurales; Instituto de Consejeros-Administradores: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/gb/GBSessions/previous-sessions/GB310/esp/WCMS_152118/lang--es/index.htm (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Antúnez Saiz, V.I.; Ferrer Castañedo, M. El Enfoque de Cadenas Productivas y La Planificación Estratégica Como Herramientas Para El Desarrollo Sostenible En Cuba. RIPS Rev. Investig. Políticas Sociol. 2016, 15, 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierri, C.; Valente, A. A Feira Livre Como Canal de Comercialização de Produtos Da Agricultura Familiar. Available online: https://silo.tips/download/a-feira-livre-como-canal-de-comercializaao-de-produtos-da-agricultura-familiar (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Lonij, V.P.A.; Fiot, J.-B. Chapter 8—Cognitive Systems for the Food–Water–Energy Nexus. In Handbook of Statistics; Gudivada, V.N., Raghavan, V.V., Govindaraju, V., Rao, C.R., Eds.; Cognitive Computing: Theory and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 35, pp. 255–282. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, C.-C.; Wang, Y.-M. Decisional Factors Driving Organic Food Consumption: Generation of Consumer Purchase Intentions. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1066–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzatti, T.C.; Sampaio, C.A.C.; Turnes, V.A. Novas relações entre agricultores familiares e consumidores: Perspectivas recentes no Brasil e na França. Organ. Rurais Agroind. 2014, 16, 363–375. Available online: http://www.revista.dae.ufla.br/index.php/ora/article/view/852/453 (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Schneider, S.; Ferrari, D.L. Cadeias curtas, coopera ção e produtos de qualidade na agricultura familiar: O Processo de Relocalização da Produção Agroalimentar em Santa Catarina. Organ. Rurais Agroind. 2015, 17. Available online: www.revista.dae.ufla.br/index.php/ora/article/view/949 (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Andrade, C.M.; Ayaviri, D. Demanda y Consumo de Productos Orgánicos en el Cantón Riobamba, Ecuador. Inf. Tecnol. 2018, 29, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras Díaz, J.; Paredes Chauca, M.; Turbay Ceballos, S. Circuitos cortos de comercialización agroecológica en el Ecuador. Idesia Arica 2017, 35, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.; Heinze, K.L.; DeSoucey, M. Forage for Thought: Mobilizing Codes in the Movement for Grass-Fed Meat and Dairy Products. Adm. Sci. Q. 2008, 53, 529–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Neira, D.; Simón, X.; Copena, D. Agroecological public policies to mitigate climate change: Public food procurement for school canteens in the municipality of Ames (Galicia, Spain). Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 45, 1528–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lécuyer, L.; Alard, D.; Calla, S.; Coolsaet, B.; Fickel, T.; Heinsoo, K.; Henle, K.; Herzon, I.; Hodgson, I.; Quétier, F.; et al. Chapter One—Conflicts between Agriculture and Biodiversity Conservation in Europe: Looking to the Future by Learning from the Past. In Advances in Ecological Research; Bohan, D.A., Dumbrell, A.J., Vanbergen, A.J., Eds.; The Future of Agricultural Landscapes, Part III; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 65, pp. 3–56. [Google Scholar]

- Soler Montiel, M.; Rivera Ferré, M.G. Agricultura Urbana, Sostenible y Soberanía Alimentaria: Hacia una Propuesta de Indicadores Desde la Agroecología. In Proceedings of the Sociología y sociedad en España [Recurso Electrónico]: Hace Treinta Años, Dentro de Treinta Años: X Congreso Español de Sociología, Pamplona, Spain, 1–3 July 2010; Universidad Pública de Navarra: Pamplona, Spain; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- Kremen, C.; Iles, A.; Bacon, C. Diversified Farming Systems: An Agroecological, Systems-Based Alternative to Modern Industrial Agriculture. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaconu, A.; Mercille, G.; Batal, M. The Agroecological Farmer’s Pathways from Agriculture to Nutrition: A Practice-Based Case from Ecuador’s Highlands. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2019, 58, 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deaconu, A.; Berti, P.R.; Cole, D.C.; Mercille, G.; Batal, M. Agroecology and Nutritional Health: A Comparison of Agroecological Farmers and Their Neighbors in the Ecuadorian Highlands. Food Policy 2021, 101, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipio de Pillaro. Datos Generales. 2023. Available online: https://www.pillaro.gob.ec/?page_id=171 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Trabelsi, M.; Mandart, E.; Le Grusse, P.; Bord, J.-P. How to Measure the Agroecological Performance of Farming in Order to Assist with the Transition Process. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briquel, V.; Vilain, L.; Bourdais, J.L.; Girardin, P.; Mouchet, C.; Viaux, P. La méthode IDEA (indicateurs de durabilité des exploitations agricoles): Une démarche pédagogique. Ingénieries Eau-Agric.-Territ. 2001, 25, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Clerino, P.; Fargue-Lelièvre, A.; Meynard, J.-M. Stakeholder’s Practices for the Sustainability Assessment of Professional Urban Agriculture Reveal Numerous Original Criteria and Indicators. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 43, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahm, F.; Viaux, P.; Vilain, L.; Girardin, P.; Mouchet, C. Assessing Farm Sustainability with the IDEA Method—From the Concept of Agriculture Sustainability to Case Studies on Farms. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 16, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahm, F.; Viaux, P.; Vilain, L.; Girardin, P.; Mouchet, C.; Häni, F.J.; Pintér, L.; Herren, H.R. Farm Sustainability Assessment Using the IDEA Method. From the Concept of Farm Sustainability to Case Studies on French Farms; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Bern, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zahm, F.; Ugaglia, A.A.; Barbier, J.-M.; Boureau, H.; del’Homme, B.; Gafsi, M.; Gasselin, P.; Girard, S.; Guichard, L.; Loyce, C.; et al. Evaluating Sustainability of Farms: Introducing a New Conceptual Framework Based on Three Dimensions and Five Key Properties Relating to the Sustainability of Agriculture; The IDEA Method Version 4; European IFSA: Gujarat, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Iakovidis, D.; Gadanakis, Y.; Park, J. Farm-Level Sustainability Assessment in Mediterranean Environments: Enhancing Decision-Making to Improve Business Sustainability. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2022, 15, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopin, P.; Mubaya, C.P.; Descheemaeker, K.; Öborn, I.; Bergkvist, G. Avenues for Improving Farming Sustainability Assessment with Upgraded Tools, Sustainability Framing and Indicators. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burin, D.; Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura (IICA); Instituto Nacional de Tecnologia Agropecuaria, B.A. (Argentina) (INTA). Manual de Facilitadores de Procesos de Innovación Comercial, 1st ed.; Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura (IICA): San José, Costa Rica, 2017; ISBN 978-92-9248-715-7. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, D.; Grisa, C.; Niederle, P. Inovações e novidades na construção de mercados para a agricultura familiar: Os casos da Rede Ecovida de Agroecologia e da RedeCoop. Redes 2020, 25, 135–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, E.; dos Santos Barros, S.E.; da Silva Sugai, M.O.; Vieira, D.D.; Freitas, H.R.; Neto, J.R.C. Short Commercialization Circuits: Contributions and Challenges for the Strengthening of Family Farming. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 2021, 8, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, R. Sistemas de producción agrícola sostenible. Rev. Tecnol. Marcha 2009, 22, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, D.V. Educação para o consumo ético e sustentável. REMEA—Rev. Eletrôn. Mestr. Educ. Ambient. 2006, 16, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, M.B.; Ochoa, J.J.; Richeri, M.; Molares, S.; Pozzi, C.; Castíllo, L.; Chamorro, M.; del Aigo, J.C.; Morales, D.; Ladio, A. La subsistencia de las comunidades rurales de la Patagonia árida. Leisa-Rev. Agroecol. 2015, 4, 13–29. Available online: https://leisa-al.org/web/index.php/volumen-31-numero-4/1329-las-mujeres-y-las-plantas-la-subsistencia-de-las-comunidades-rurales-de-la-patagonia-arida (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Solomon, S.J.; Mathias, B.D. The Artisans’ Dilemma: Artisan Entrepreneurship and the Challenge of Firm Growth. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 106044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, R.; Bogue, J.; Repar, L. Farmers’ Markets as Resilient Alternative Market Structures in a Sustainable Global Food System: A Small Firm Growth Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boenzi, F.; Digiesi, S.; Facchini, F.; Silvestri, B. Life Cycle Assessment in the Agri-Food Supply Chain: Fresh versus Semi-Finished Based Production Process. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, D.; Alonso, N.; Herrera, P.M. Políticas Alimentarias Urbanas Para La Sostenibilidad. Análisis de Experiencias En El Estado Español, En Un Contexto Internacional|CSCAE 2030. Available online: http://www.observatorio2030.com/documento/politicas-alimentarias-urbanas-para-la-sostenibilidad-analisis-de-experiencias-en-el (accessed on 17 February 2023).

| Scale | Indicator | Value | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agroecological sustainability | Diversity of annual or temporary crops | 15 | 41 |

| Perennial crop diversity | 15 | ||

| Plot size | 8 | ||

| Soil protection techniques | 3 | ||

| Socio-territorial sustainability | Social participation | 7 | 34 |

| Commercial and multi-activity services | 5 | ||

| Quality of the food produced | 12 | ||

| Involvement in associations | 10 | ||

| Economic sustainability | Income effectiveness | 10 | 25 |

| Self-financing capacity | 15 | ||

| Total Rating | 100 | 100 |

| Variable | Data | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 100 |

| Age | 15–28 | 0 |

| 29–39 | 32 | |

| 40–50 | 38 | |

| 50–65 | 30 | |

| Level of education | None | 0 |

| Primary | 77 | |

| High school | 18 | |

| University | 5 | |

| Marital status (1–3) | Married | 88 |

| Single | 7 | |

| Divorced | 5 | |

| Number of family members | 1 | 0 |

| 2 to 4 | 73 | |

| 5 or 6 | 27 | |

| Productive credit | Yes | 4 |

| No | 96 | |

| Owner of the land | Own | 89 |

| Lease | 11 | |

| Occupied | 0 | |

| Short Commercialization Circuits (SCCs) | Home deliveries | 40 |

| Local markets | 35 | |

| Agroecological fairs | 25 | |

| Price | 52 | |

| The disadvantage of the commercialization of agroecological products | Competition | 30 |

| No disadvantages | 18 |

| Group | Product |

|---|---|

| Gramine | Corn |

| Vegetable | Lettuce |

| Zucchini | |

| Onion | |

| Chard | |

| Leek | |

| Cabbage | |

| Broccoli | |

| Pea | |

| Garlic | |

| Cauliflower | |

| Pepper | |

| Bean | |

| Lima beans | |

| Legume | Radish |

| Beetroot | |

| Tuber | Potato |

| White melloco | |

| Red melloco | |

| Tomato (tree) | |

| Babaco | |

| Fruit | Strawberry |

| Raspberry |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franco-Crespo, C.; Cordero-Ahiman, O.V.; Vanegas, J.L.; García, D. Short Commercialization Circuits and Productive Development of Agroecological Farmers in the Rural Andean Area of Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086944

Franco-Crespo C, Cordero-Ahiman OV, Vanegas JL, García D. Short Commercialization Circuits and Productive Development of Agroecological Farmers in the Rural Andean Area of Ecuador. Sustainability. 2023; 15(8):6944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086944

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranco-Crespo, Christian, Otilia Vanessa Cordero-Ahiman, Jorge Leonardo Vanegas, and Dario García. 2023. "Short Commercialization Circuits and Productive Development of Agroecological Farmers in the Rural Andean Area of Ecuador" Sustainability 15, no. 8: 6944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086944

APA StyleFranco-Crespo, C., Cordero-Ahiman, O. V., Vanegas, J. L., & García, D. (2023). Short Commercialization Circuits and Productive Development of Agroecological Farmers in the Rural Andean Area of Ecuador. Sustainability, 15(8), 6944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086944