Evolutionary Game Analysis of Governmental Intervention in the Sustainable Mechanism of China’s Blue Finance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Literature Review and Hypotheses

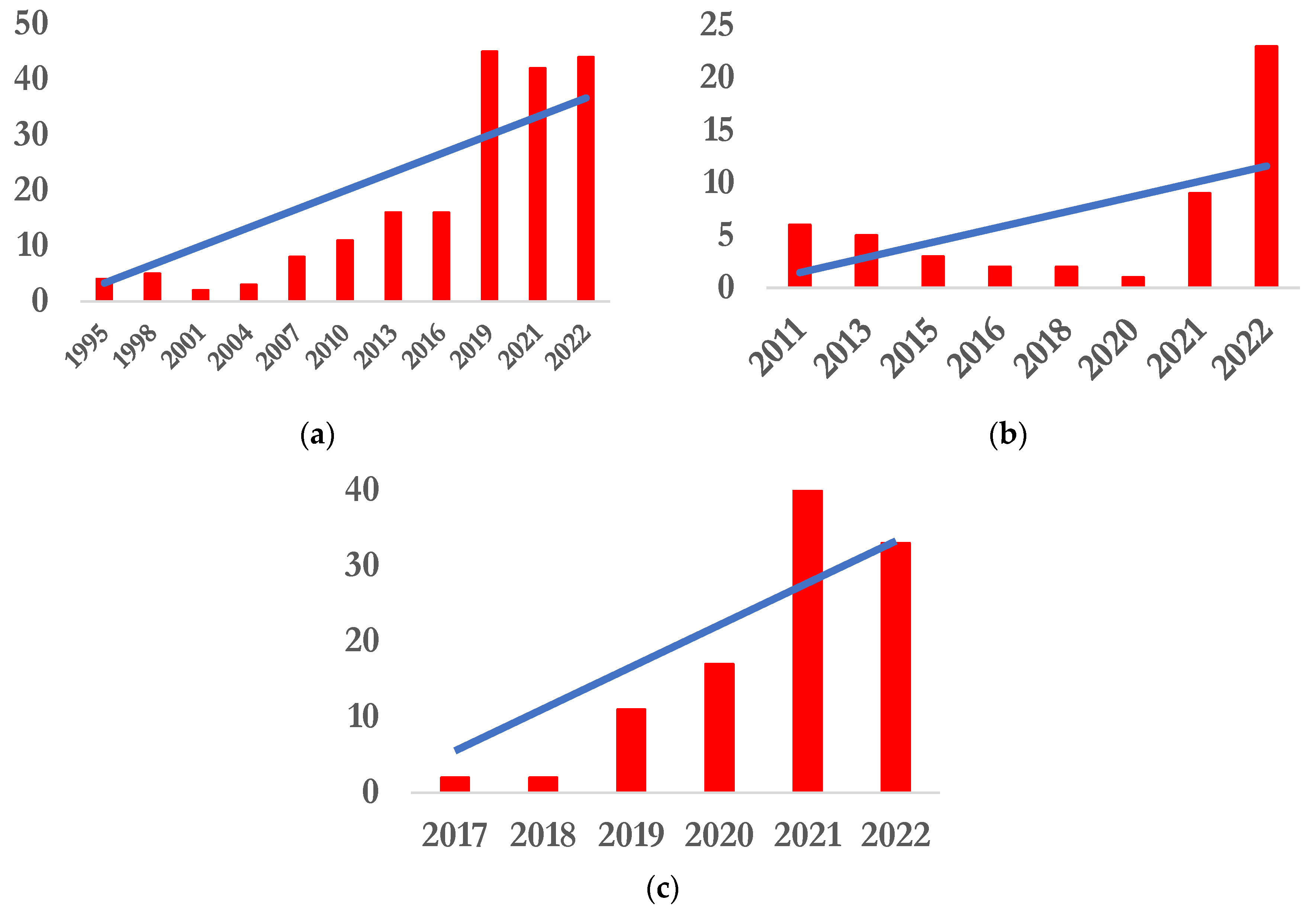

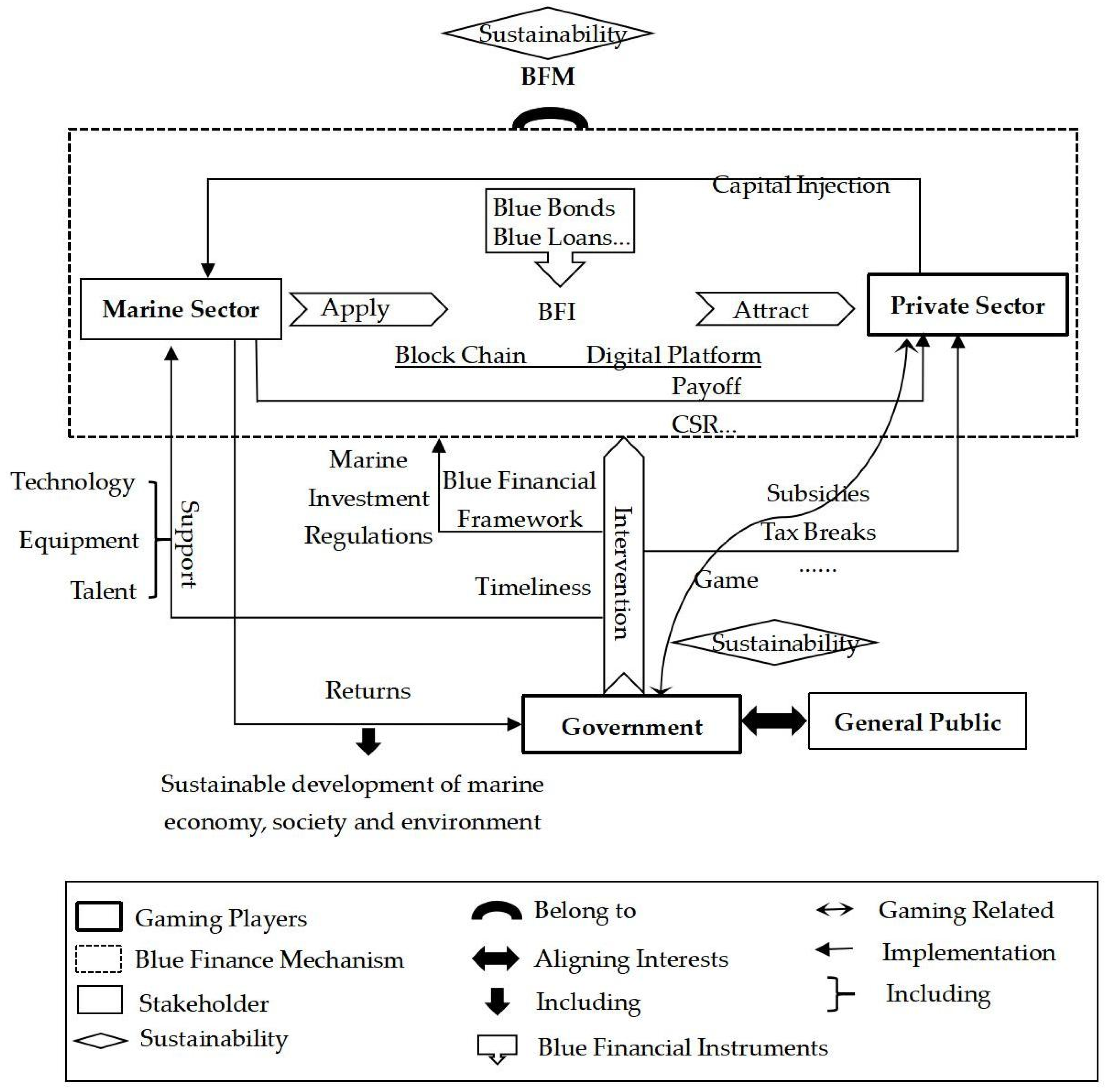

2.1. Literature Review on the Background of BFM

2.2. Governmental Intervention in BFM

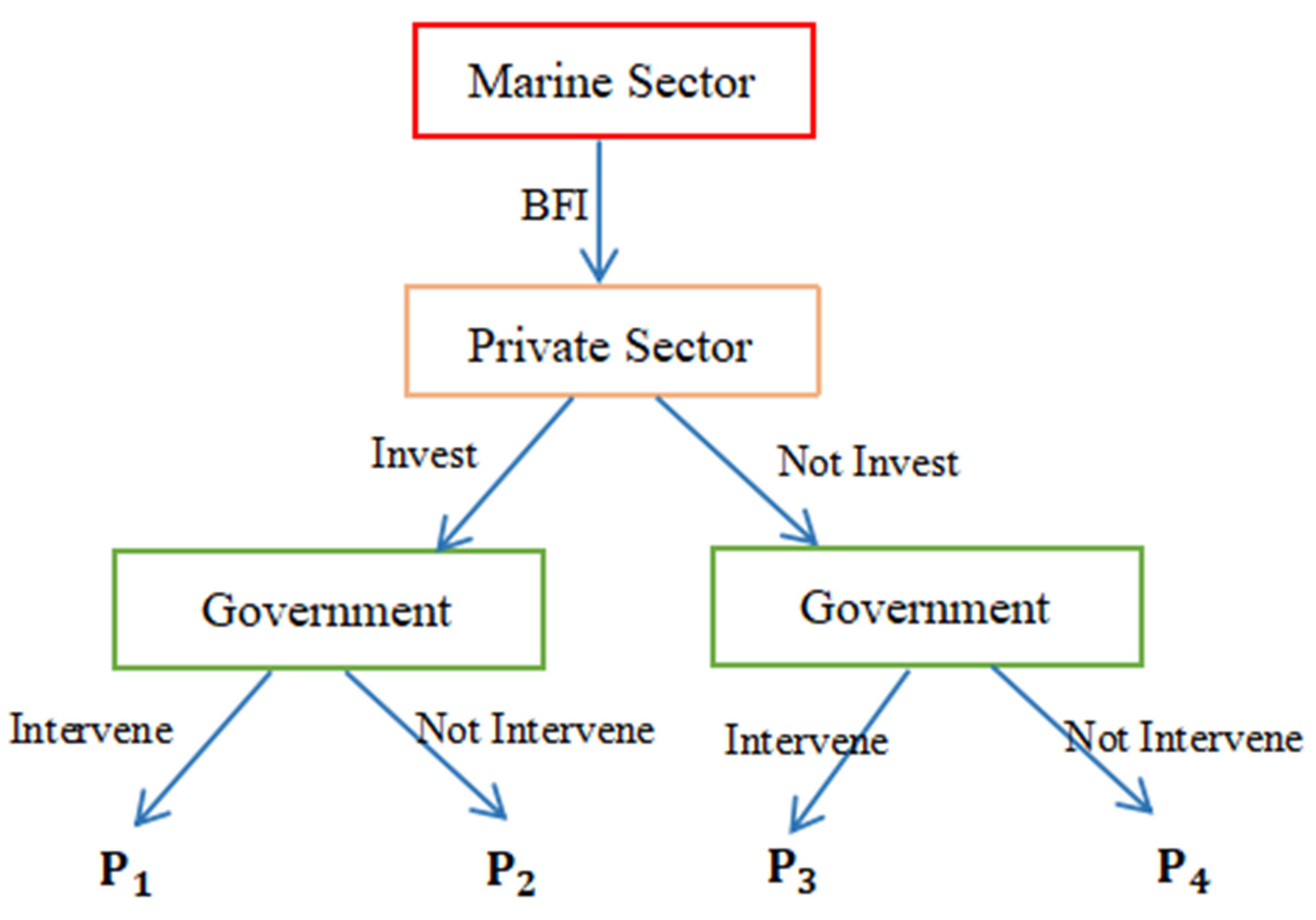

2.3. Game Model and Hypothesis

2.3.1. Model Hypothesis

- (1)

- In order to fulfil its goal of luring investors to the maritime industry, the Chinese government mostly intervenes in the BFM through incentives. Therefore, is the Chinese government’s set of game strategies. The set of gaming tactics for the private sector is based on its strategic requirements.

- (2)

- Tirumala and Tiwari [8] noted that the final beneficiary of most blue finance projects is a private sector developer. and are documented as the income that the private sector can make by investing in the maritime sector with and without governmental assistance, and > > 0. By intervening in the BFM, the Chinese government encourages the private sector to invest through incentives and uses the “visible hand” to macro-regulate the growth of the maritime sector, increasing its economic efficiency [57]. The private sector gains from the marine industry’s improved economic efficiency and greater income.

- (3)

- The revenue that the private sector may generate by investing in non-marine industries is thus designated as , and >. Humankind’s grasp of the seas is less than that of land [48], which, along with the significant uncertainty of marine investments, leads the private sector to prefer more developed non-marine industries [58]. The marine sector focuses on the peaceful cohabitation of marine economic society and the environment in the process of establishing the BFM, fostering the creation of marine ecosystems [47]. As a result, by investing in the development of the marine sector and the management of marine ecosystems, the private sector is assuming corporate social responsibility, acquiring social repute and increasing its visibility [59].

- (4)

- Government policies can allocate funding to support research on and development of market-based instruments, reduce perverse subsidies, and create positive subsidies that fund the transition to more sustainable industries [60]. Regulations introduced by the Chinese government have decreased the uncertainty of investment in the maritime sector, and the intangible advantages achieved by enterprises are recorded as [61,62]. Governments have important roles to play in enabling businesses to reduce their environmental damages and produce positive marine impacts [63]. Sustainable growth of the ocean economy also provides the Chinese government with intangible benefits such as public acclaim, which is denoted as . Such a return will not always be measured by standard performance measures but will sometimes include a range of social and ecological benefits, and these need to be included [64]. Similarly, when PSIMS is adopted, the Chinese government earns money through taxes. The Chinese government hopes to achieve the twin goals of safeguarding seas and coastlines while also expanding its potential contribution to sustainable development, including promoting human well-being and lowering environmental dangers and ecological scarcity through creative approaches [26]. The measurement of intangible benefits is inherently difficult; therefore, there is no relationship between the size of and .

- (5)

- If the Chinese government intervenes, it receives revenue as , but if the Chinese government does not intervene, it receives revenue as , and so it may be stated that > > 0. Furthermore, the private sector chooses to invest in non-marine businesses, and the Chinese government obtains money recorded as . Xu et al. [57] demonstrated through empirical study that interfering in the assumption of the BFM allows the Chinese government to obtain more economic benefits than not intervening. Non-marine (land-based) industries are more established and profitable than maritime industries. Therefore, the Chinese government gains from the development of marine industries are lower than the gains harvested from non-marine industries. However, there is no strict limit on the size of and .

- (6)

- To encourage the private sector to participate in the maritime sector, the Chinese government gives subsidies to invest in the private sector, the cost of which is recorded as . Subsidies are offered by the Chinese government to reduce the cost of private sector investment while simultaneously reducing the pressure to invest [65]. Subsidies, tax breaks, and other incentives, on the other hand, raise the Chinese government’s financial spending and burden the Chinese government [66]. A cost–benefit analysis is similar to how the Chinese government assesses costs and consequences [67,68,69]. According to some studies, investment firms have been discouraged from participating in the marine sector due to the high risks and unpredictability of investment income [70]. Chinese government subsidies have a significant role in encouraging the private sector to invest in the marine sector.

2.3.2. Basic Hypothesis

2.3.3. Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium Analysis

3. Model Analysis

3.1. Evolutionary Game Replication Dynamic Equation

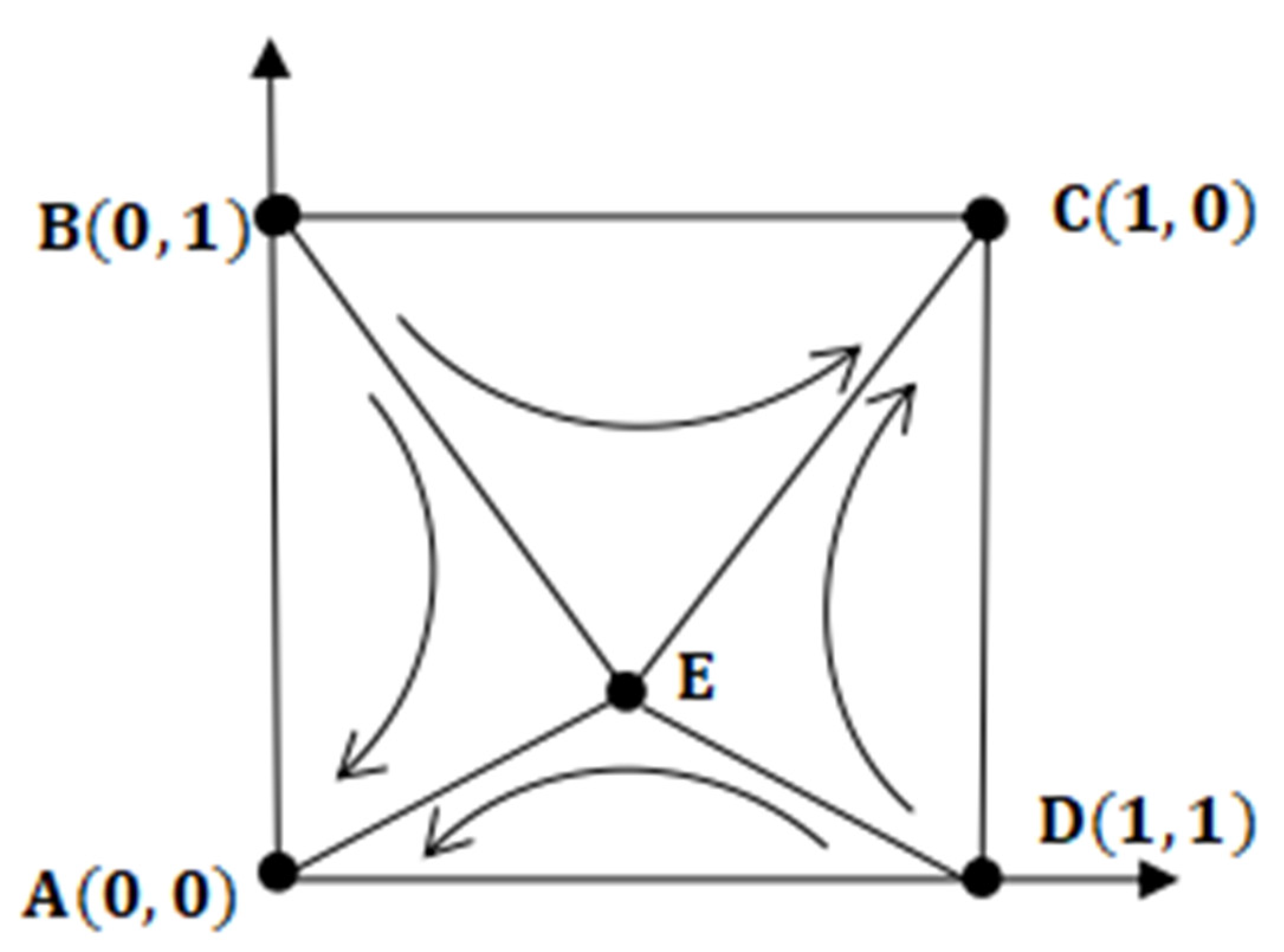

3.2. Equilibrium Point and Stability Analysis

- (1)

- When , there is always , meaning that the system will reach the evolutionary steady state regardless of the values in the definition domain; similarly, when the probability of Chinese government subsidies is , the revenue of the private sector choosing to invest or not in the marine industry is unaffected. When , there is always , which means the system will reach an evolutionary steady state regardless of the value taken in the definition domain; when the probability of the private sector investing in the marine industry is , it makes no difference whether the Chinese government chooses to subsidize or not.

- (2)

- When , the evolutionary game will achieve a stable state; and are two feasible stable points. Alternatively, when at , /, the evolutionary game will reach a stable state, and is the only viable stable point. Therefore, Chinese government stability by intervention in BFM to fund the private sector is an evolutionary approach. Similar to this, governmental non-intervention for subsidies is the evolutionary stable strategy, where and is the only conceivable stable position.

- (3)

- When , then and are two conceivable stable state points; however, at , / will attain a stable state, and is the sole possible stable point, implying that investing in the marine sector is an evolutionary stable strategy for the private sector. Similarly, and is the only conceivable stable point, and avoiding engaging in the maritime business is a stable evolutionary strategy for the private sector.

- (4)

- The equilibrium point’s phase diagram may be obtained; when () falls in the BECD area, the system will converge to the ideal state in which the Chinese government decides to subsidize and the private sector opts to invest in the maritime sector. When () falls in the ABEC area, the evolutionary game results in an unfavorable state in which the Chinese government decides not to subsidize and the private sector opts not to invest in the maritime industry.

4. Numerical Simulation Analysis

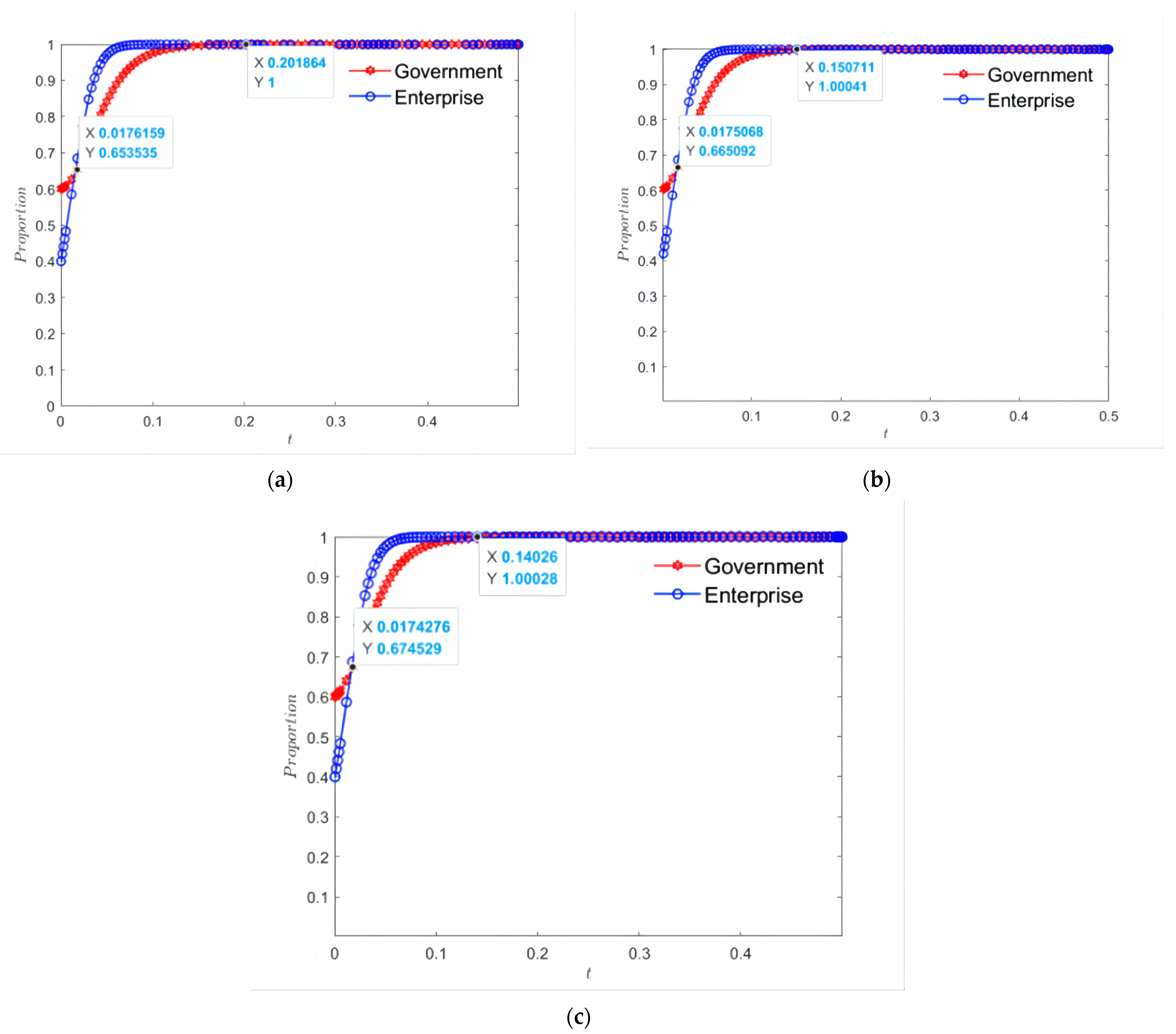

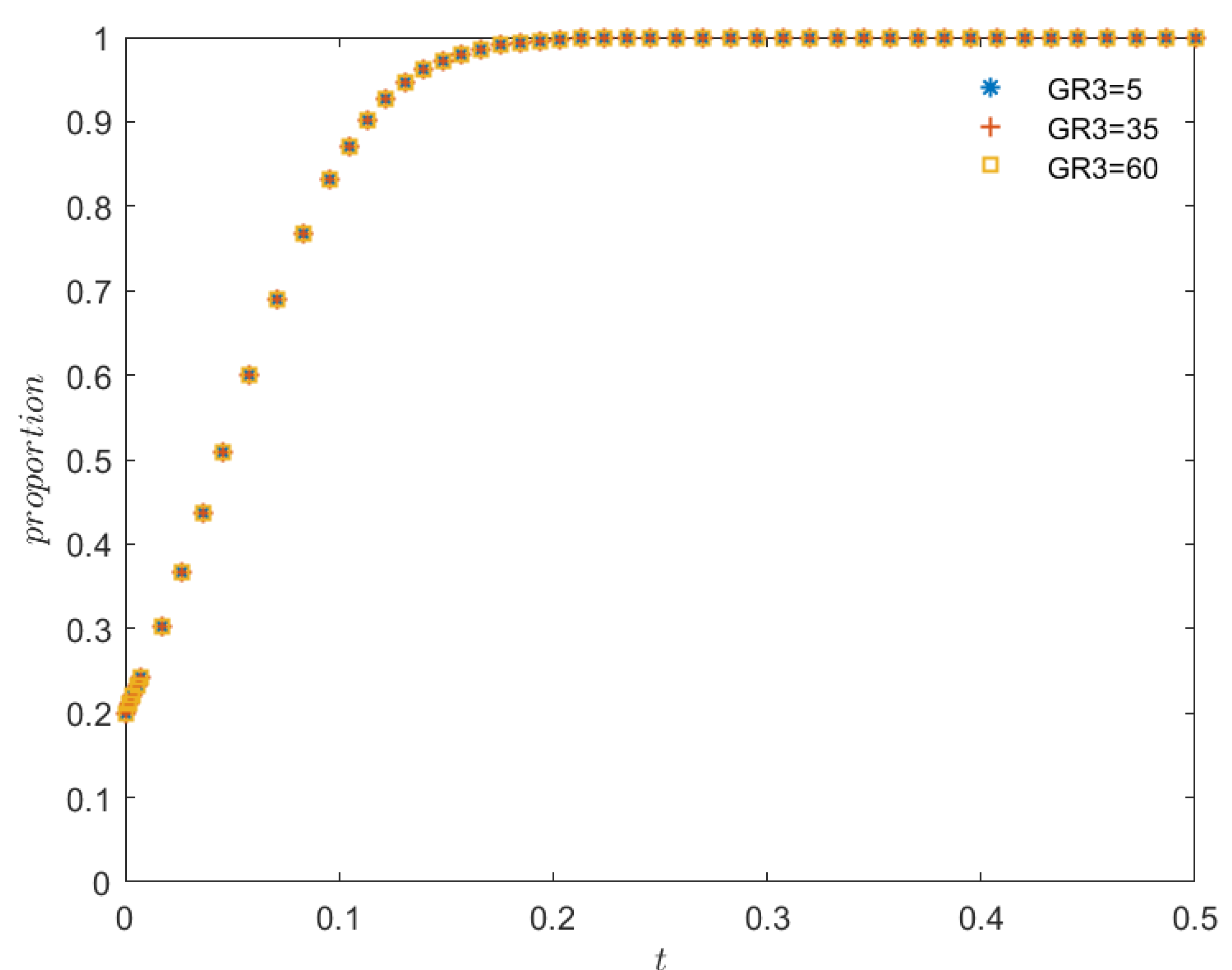

4.1. Effect of Different Initial Probabilities on the Stability of Evolving Game Systems

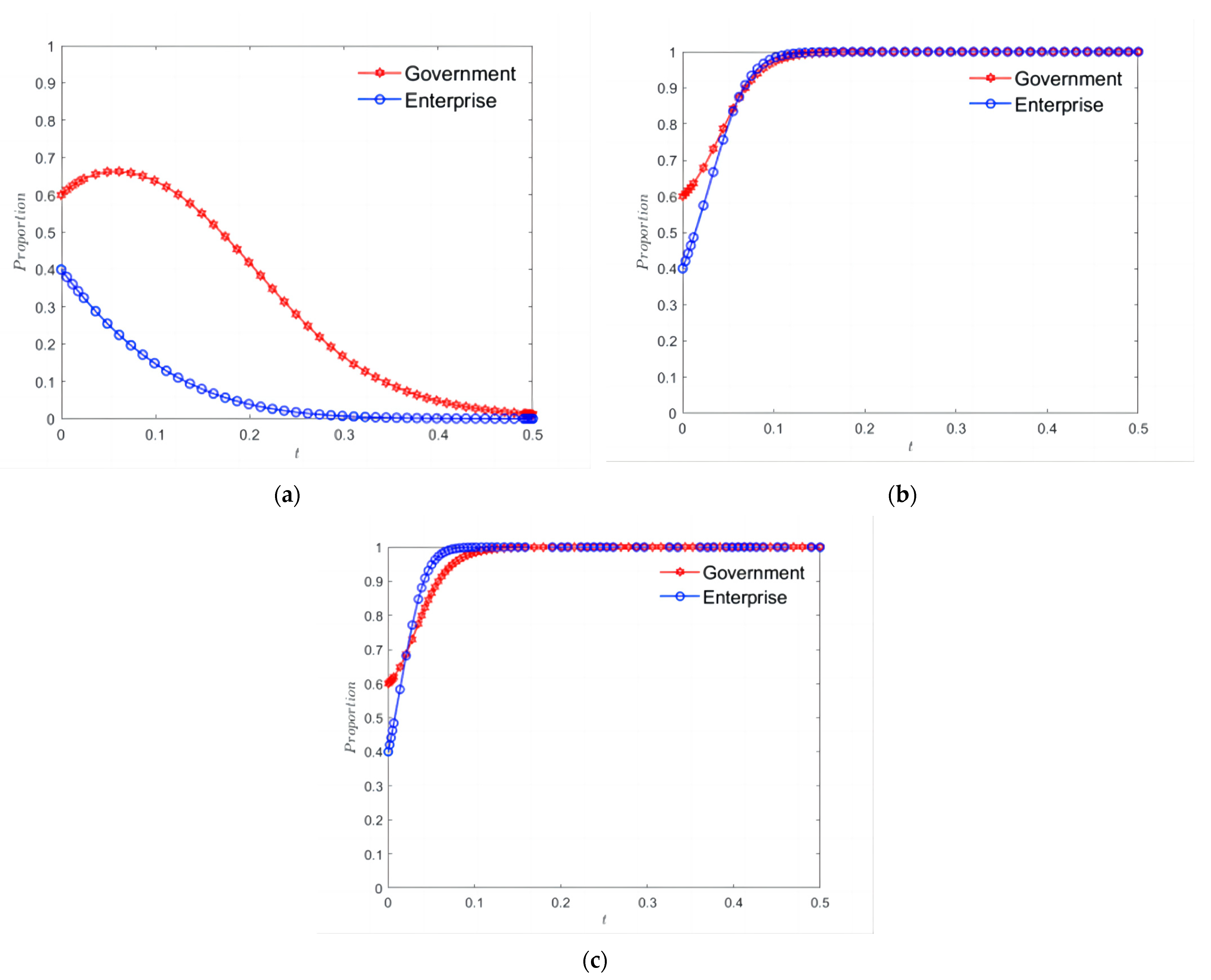

4.2. Effect of Chinese Government on the Stability of Evolutionary Game Systems

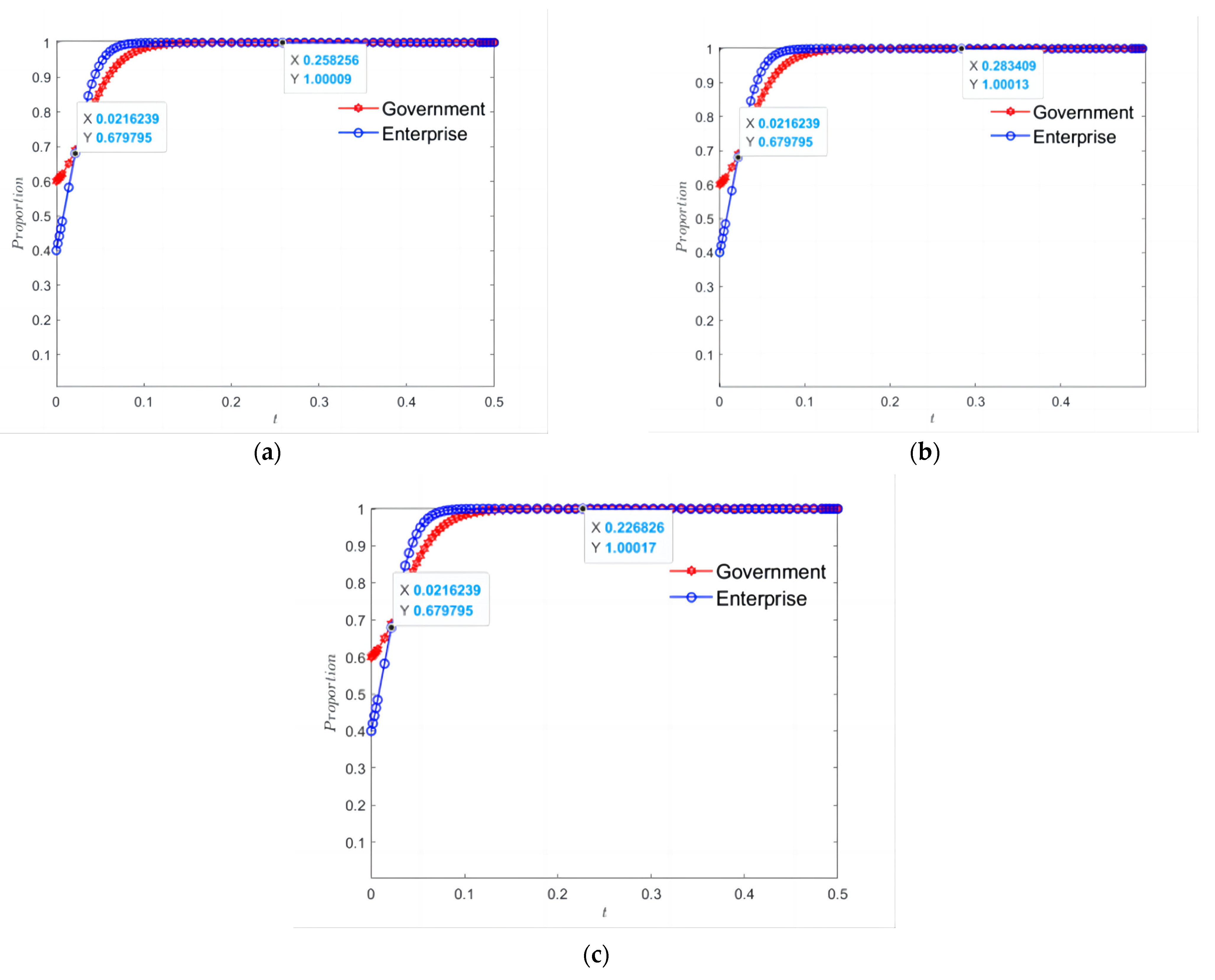

4.3. Effect of the Private Sector Parameters on the Stability of the Evolutionary Game System

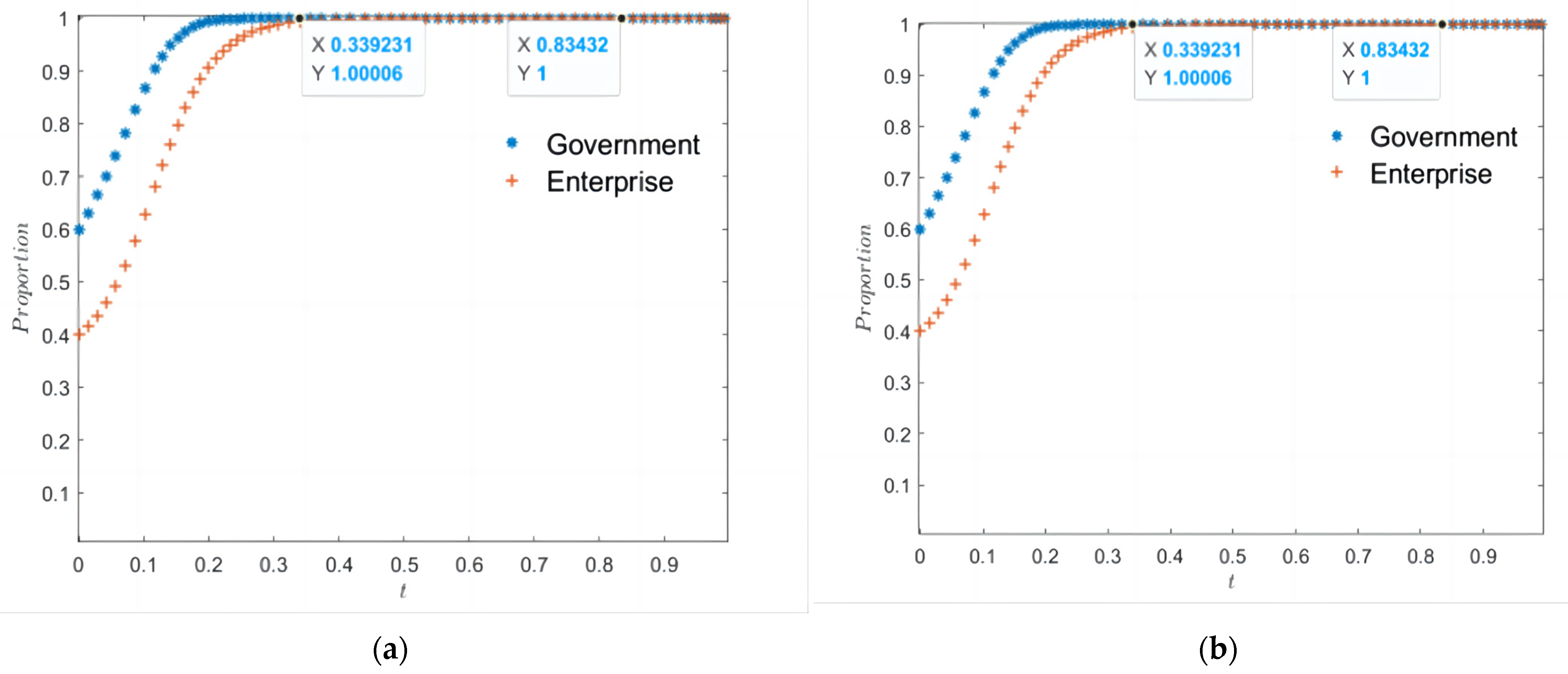

4.4. Effects of Other Parameters (, )

4.5. Discussion of Results

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Governmental intervention can have a substantial impact on advancing the sustainable development of the BFM in China. The effectiveness of Chinese government intervention in blue finance is demonstrated by numerical simulations of the Chinese case. Moreover, public finance and development finance can be enhanced through governmental intervention in the long-term blue finance system. However, the Chinese case also illustrates that Chinese government intervention puts pressure on public finances, and thus the degree of Chinese government intervention needs to be balanced. In addition, the Chinese government’s participation in policy formulation can play a vital role in fostering the sustainable development of the BFM and balancing ocean economic growth with environmental preservation. This can contribute to the sustainable growth of the ocean economy, the promotion of maritime infrastructure, and the preservation of marine life. Additionally, the Chinese government plays a crucial role in facilitating access to capital for sustainable marine projects through the provision of funding. This support can overcome obstacles to investment, such as high perceived risks, and incentivize private investment in the marine sector. Hence, governmental involvement in the sustainable development of the BFM is crucial in ensuring its success.

- (2)

- The participation of the Chinese government’s intervention in the BFM can play a crucial role in fostering investor confidence and trust. Governmental involvement in policy formulation can create a stable and predictable investment climate that emphasizes transparency and accountability, which in turn can increase investor confidence in the BFM and incentivize private investment in sustainable marine projects. The Chinese government has also increased its intervention in the blue financial sector based on this. Additionally, the Chinese government’s role in facilitating access to capital for sustainable marine projects also contributes to the enhancement of investor confidence and trust in the BFM. By providing support to overcome barriers to investment and signaling its commitment to the ocean economy, the Chinese government can encourage private investment in the BFM and contribute to its success. In conclusion, governmental intervention is vital in enhancing investor confidence and trust in the blue financial mechanism. By fostering a stable investment environment, facilitating access to capital, and supporting sustainable marine projects, the Chinese government can play a key role in attracting private investment and promoting the sustainable development of the BFM. Moreover, the effectiveness of Chinese government intervention in the BFM also serves as a guide for future research in marine investment and government management.

- (3)

- The sooner the Chinese government intervenes in BFM, the more inclined the private sector is to invest in the marine industry. Timeliness is key in this regard, as prompt governmental intervention can influence the investment decisions made by the private sector. As a result, the Chinese government should make suitable decisions and play a macro-regulatory role as soon as possible.

- (4)

- Chinese government subsidies are crucial in having a cooperative attitude in the gaming process between the private sector and the Chinese government. This assures a modest rate of return, allays the private sector’s fears, and encourages investment. However, the amount of Chinese government subsidies that may be granted is limited, and exceeding these limits will result in the Chinese government taking a hands-off stance. Chinese government subsidies have increased the incentives for the private sector to participate in the marine industry. As a result, the Chinese government must accurately grasp the threshold of the amount of subsidies, calculating its own costs and benefits in order to optimize the use of subsidies to pique the private sector’s interest in the marine industry. Furthermore, subsidies can be used to reduce the private sectors’ investment risk and maximize investment income. In addition, activating private sector investment in the marine sector has enabled corporate social responsibility to be demonstrated. The Chinese government has used tax breaks and subsidies to help stimulate the private sector investment in the marine sector, particularly in areas such as aquaculture and offshore wind power. This approach has provided valuable lessons for other countries seeking to leverage financial mechanisms to support similar objectives.

- (5)

- Intangible benefits obtained by the private sector when investing in the marine industry in China, such as governmental honors and public praise, have had a significant effect in contributing to the decision to choose the “invest” strategy. When the advantages of investing in the marine sector are almost equivalent to those of investing in the non-marine industry, the private sector is more likely to choose the marine industry owing to intangible benefits.

6. Recommendations

6.1. Limitations and Future Work

6.2. Recommendations

- (1)

- To enhance investment in the marine sector, the Chinese government’s proactive involvement in the BFM is of utmost importance. The Chinese government’s early intervention in the BFM can have a significant and positive impact on the growth and development of the marine industry. By taking proactive measures, the Chinese government can also minimize the potential risks associated with investment in the marine sector, thereby increasing the trust and confidence of investors. This, in turn, can lead to the establishment of a more sustainable and profitable marine industry. Therefore, the Chinese government’s early engagement in BFM plays a critical role in promoting investment and fostering sustainable development in the ocean economy, society, and environment.

- (2)

- In order to foster and advance the development of the marine sector, the Chinese government must make a concerted effort to increase subsidies and diversify its incentive systems. As emphasized by Dencer-Brown et al. [26], the Chinese government must take on a leading role in the ocean economy and actively work to encourage investment in this important sector. One effective way to achieve this is by utilizing flexible economic instruments and incentives, which can provide financial support to the private sector and help reduce the cost of investment in the marine industry. The Chinese government can establish financial subsidies and implement preferential policies for companies that invest in sustainable and environmentally friendly practices. This will not only encourage the private sector’s participation, but also create a favorable investment environment that can lead to increased investment and economic growth in the marine sector. In addition, by providing necessary financial support, the Chinese government can help mitigate any potential risks associated with investment in the marine sector, thus increasing investor confidence and promoting a more sustainable and profitable industry [102]. This can be accomplished through targeted measures such as the development of new financial instruments, the introduction of tax breaks or subsidies, and the provision of technical assistance to private sector entities. In conclusion, the Chinese government has a vital role to play in promoting investment in the marine sector. By increasing subsidies, utilizing flexible economic instruments and incentives, and providing ongoing financial assistance to the private sector, the Chinese government can help create a sustainable and profitable marine industry that contributes to the overall sustainable development of the ocean economy, society, and environment.

- (3)

- To further incentivize private sector investment in the marine industry, the Chinese government should consider enhancing the form of rewards it provides. While monetary incentives such as tax breaks or subsidies are important, non-monetary rewards can also play a crucial role in encouraging the private sector’s participation. These rewards can include official recognition, media publicity, and various forms of commendation for the contributions made by private sector entities to the growth and expansion of the marine sector. These non-monetary incentives can help to create a positive perception of the private sector and the marine sector, increasing investment and growth. By providing a comprehensive set of rewards that includes both monetary and non-monetary incentives, the Chinese government can create a more appealing and attractive investment environment, encouraging the private sector’s involvement and promoting the sustainable development of the ocean economy, society, and environment.

- (4)

- The Chinese government should promote public awareness and education about the importance of marine conservation and sustainable practices. It is recommended that the private sector prioritize investments in sustainable marine projects that can bring about economic growth, job creation, and environmental protection. To further encourage responsible investment, it is crucial that the private sector adopts sustainable business practices and incorporates the standards of environmental, social, and governance into their operations. In addition, collaboration between the private sector and the Chinese government, as well as other stakeholders, is crucial for promoting sustainable development in the ocean economy, society, and environment.

- (5)

- Support the development of local, small-scale marine sectors that prioritize sustainability and environmental stewardship. These sectors often have a greater incentive to prioritize sustainability and environmental stewardship as they are more directly impacted by the health of the local marine ecosystem. Governments can invest in training programs and provide technical assistance to help small businesses adopt best practices and improve their sustainability.

6.3. Future Studies

- (1)

- Risk management in the blue finance mechanism in China: Future research could explore the risks associated with China’s blue finance, such as environmental risks, credit risks, and operational risks. It could also investigate the effectiveness of China’s current risk management practices and suggest improvements.

- (2)

- Innovative blue financing mechanisms for Chinese marine projects: Future research could explore innovative blue financing mechanisms for Chinese marine projects, such as impact investment, crowdfunding, the integration of emerging financing technologies (such as blockchain, artificial intelligence, and big data) with marine finance (such as marine insurance, shipping finance, and marine renewable energy finance), and then analyze the benefits and drawbacks of these mechanisms and their potential for promoting sustainable marine development.

- (3)

- Internationalization of China’s marine finance: Future research could explore the potential for China’s blue finance to expand internationally, analyze the current international marine finance market and identify opportunities for Chinese firms to enter this market, and examine the challenges that Chinese firms may face in competing internationally in this field.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BFM | Blue finance mechanism |

| BFIs | Blue financial instruments |

| CINii | Citation Information National Institute of Informatics |

| CNKI | China National Knowledge Infrastructure |

| PSIMS | Private sector investment in the marine sector |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| WOS | Web of Science |

Appendix A

| Debt Investments | Issuers | Bond Abbreviation | Issue Size (Billion Yuan) | Issue Rate (%) | Where The Money is Invested |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qingdao Water Affairs Group Co., Ltd. 2020 Phase I Green Medium Term Notes (Blue Bond) | Qingdao Water Group Co. | 20 Qingdao Water Gn001 (Blue Bond) | 3 | 3.63 | Seawater Desalination |

| Fujian Huadian Fury Energy Development Company Limited 2021 Public Issue Of Green Renewable Corporate Bonds (Phase Ii) (Blue Bond) (Variety I) | Fujian Huadian Frui Energy Development Co. | G21Fry3 | 10 | 3.29 | Offshore Wind Power |

| Huadian Fuyuan New Energy Company Limited Third Green Medium Term Note 2021 (Blue Bond) | Huadian Foss Energy Limited | 21 Fn Gn003 (Blue Bond) | 10 | 3.05 | Offshore Wind Power |

| Guodian Power Development Co., Ltd. 2021 Fourth Green Medium Term Notes (Blue Bond) (Variety Ii) | Guodian Power Development Co. | 21 Guodian Gn004B (Blue Bond) | 2 | 3.40 | Offshore Wind Power |

| Guodian Power Development Company Limited Fourth Green Medium Term Note 2021 (Blue Bond) (Variety I) | Guodian Power Development Co. | 21 Guodian Gn004A (Blue Bond) | 6 | 3.05 | Offshore Wind Power |

| Zhejiang Energy Group Limited Third Green Medium Term Note 2021 (Blue Bond) | Zhejiang Energy Group Co. | 21 Zhejiang Energy Gn003 (Blue Bond) | 5 | 2.95 | Offshore Wind Power |

| Huaneng International Power Jiangsu Energy Development Co., Ltd. 2021 Phase I Green Medium Term Notes (Blue Bond/Carbon Neutral Bond) | Huaneng International Power Jiangsu Energy Development Co. | 21 Huaneng Jiangsu Mtn001 (Carbon Neutral Bond) | 3 | 2.95 | Offshore Wind Power |

| Public Issue Of Green Corporate Bonds 2022 For Professional Investors (Phase I) (Blue Bonds) By China Merchants Tong Shang Finance & Leasing Co. | China Merchants Tong Shang Finance & Leasing Co. | 22 For Lease G1 | 10 | 3.05% | Construction Of Offshore Wind Installation Vessels |

| Cgn Wind Power Limited 2022 Public Issue Of Green Corporate Bonds (Blue Bonds) For Professional Investors (Phase I) (Variety I) | Cgn Wind Power Limited | 22 Wind Power G1 | 15 | 2.95% | Offshore Wind Power |

| Cgn Wind Power Limited 2022 Public Issue Of Green Corporate Bonds (Blue Bonds) For Professional Investors (Phase I) (Variety Ii) | Cgn Wind Power Limited | 22 Wind Power G2 | 5 | 3.79% | Offshore Wind Power |

| Qingdao Water Affairs Group Co., Ltd. 2022 Phase I Green Medium Term Notes (Blue Bond) | Qingdao Water Group Co. | 22 Qingdao Water Gn001 (Blue Bond) | 2 | 3.63% | Seawater Desalination |

| Guodian Power Development Co., Ltd. 2022 Fourth Green Medium Term Notes (Blue Bond) (Variety I) | Guodian Power Development Co. | 22 Guodian Gn001A (Blue Bond) | 10 | 2.70% | Offshore Wind Power |

| Guodian Power Development Co., Ltd. 2022 Fourth Green Medium Term Notes (Blue Bond) (Variety Ii) | Guodian Power Development Co. | 22 Guodian Gn001B (Blue Bond) | 5 | 3.25% | Offshore Wind Power |

| Huaneng International Power Jiangsu Energy Development Co., Ltd. 2022 Phase I Green Medium Term Notes (Blue Bond/Carbon Neutral Bond) | Huaneng International Power Jiangsu Energy Development Co. | 22 Huaneng Jiangsu Mtn001 (Carbon Zhonghe Bond) | 5 | 2.92% | Offshore Wind Power |

References

- Baker, S.; Constant, N.; Nicol, P. Oceans justice: Trade-offs between Sustainable Development Goals in the Seychelles. Mar. Policy 2023, 147, 105357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouffray, J.B.; Blasiak, R.; Norstrom, A.V.; Osterblom, H.; Nystrom, M. The Blue Acceleration: The Trajectory of Human Expansion into the Ocean. One Earth 2020, 2, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virdin, J.; Vegh, T.; Jouffray, J.B.; Blasiak, R.; Mason, S.; Osterblom, H.; Vermeer, D.; Wachtmeister, H.; Werner, N. The Ocean 100: Transnational Corporations in the Ocean Economy. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabc8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, N.J.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Blythe, J.; Silver, J.J.; Singh, G.; Andrews, N.; Calo, A.; Christie, P.; Di Franco, A.; Finkbeiner, E.M.; et al. Towards A Sustainable and Equitable Blue Economy. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 991–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österblom, H.; Wabnitz, C.C.C.; Tladi, D. Towards Ocean Equity Blue Paper. World Resources Institute, 2020. Available online: https://www.oceanpanel.org/blue-papers/towards-ocean-equity (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Global Assessment Summary for Policymakers 2019. Available online: https://ipbes.net/document-library-catalogue/summary-policymakersglobal-assessment-laid-out (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- European Commission. The EU Blue Economy Report 2022; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; Available online: https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-05/2022-blue-economy-report_en.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2022).

- Tirumala, R.D.; Tiwari, P. Innovative Financing Mechanism for Blue Economy Projects. Mar. Policy 2022, 139, 104194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhou, Q. Definition and Connotation of Blue Economy. Mar. Econ. 2013, 3, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiiba, N.; Wu, H.H.; Huang, M.C.; Tanaka, H. How Blue Financing Can Sustain Ocean Conservation and Development: A Proposed Conceptual Framework for Blue Financing Mechanism. Mar. Policy 2022, 139, 104575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. Blue finance Adds “Golden Power” to the Marine Economy. Environ. Econ. 2022, 21, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- IODE. Project Document for the Establishment of the Ocean Data and Information Network for the European Countries in Economical Transition (Odinecet); Unesco: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Akimova, O. Ocean Data and Information Network for the European Countries in Economical Transition (ODINECET). In Proceedings of the IODE Group of Experts on Marine Information Management (GE-MIM-X), Oostende, Belgium, 3–7 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Establishing Community financial measures for the implementation of the Common Fisheries Policy and in the Area of the Law of the Sea. Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32006R0861 (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Peng, C. Blue Finance: Ningbo Marine Economy Booster. Ningbo Newsl. 2012, 6, 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. The Pioneer of Blue Finance—Qingdao Rural Credit Union Devoted Itself to the Construction of Blue Economic Zone. China Rural. Financ. 2011, 11, 62–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, K. International Blue Finance Development Logic, Basic Pattern and Practical Inspiration. Hainan Financ. 2022, 10, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J.; Huang, C.; Voyer, M.; Benzaken, D.; Watanabe, A. Blue Economy and Blue Finance Toward Sustainable Development and Ocean Governance; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Finance and Sustainability (IFS). Research on Blue Finance Practice and the Catalogue of Investment and Financing Support for Marine Industry. 2022. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/4a61d420-82b2-41e9-b2fd-b7fb0af38bba/IFC-Guidelines-for-Blue-Finance.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=ogvh-4f (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Thompson, B.S. Blue Bonds for Marine Conservation and A Sustainable Ocean Economy: Status, Trends, and Insights from Green Bonds. Mar. Policy 2022, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Zhang, W. Study on the Path of Financial Support for Development of Marine Economy in Yantai City. Reg. Econ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, L.; Donato, D.C.; Murray, B.C.; Crooks, S.; Jenkins, W.A.; Sifleet, S.; Craft, C.; Fourqurean, J.W.; Kauffman, J.B.; Marba, N.; et al. Estimating Global Blue Carbon Emissions from Conversion and Degradation of Vegetated Coastal Ecosystems. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Zhao, J. The Strategic Significance and Basic Path of Financial Support for Marine Economy in New Era. Econ. Manag. Rev. 2018, 34, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugg-Levine, A.; Emerson, J. Impact Investing: Transforming How We Make Money while Making a Difference. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2011, 6, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrea, N. New Frontiers in Philanthropy: A Guide to the New Tools and Actors Reshaping Global Philanthrpy and Social Investing. Commun. Dev. J. 2016, 51, 585–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dencer-Brown, A.M.; Shilland, R.; Friess, D.; Herr, D.; Benson, L.; Berry, N.J.; Cifuentes-Jara, M.; Colas, P.; Damayanti, E.; Garcia, E.L.; et al. Integrating Blue: How Do We Make Nationally Determined Contributions Work for Both Blue Carbon and Local Coastal Communities? Ambio 2022, 21, 1978–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Peng, Q.Y. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Enterprise Green Innovation and Green Financing in Platform Supply Chain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofbauer, J.; Sandholm, W.H. Survival of Dominated Strategies under Evolutionary Dynamics. Theor. Econ. 2011, 6, 341–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, D. On Evolutionary Game Theory and Team Reasoning. Rev. Econ. Polit. 2018, 128, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wabnitz, C.C.C.; Blasiak, R. The Rapidly Changing World of Ocean Finance. Mar. Policy 2019, 107, 103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y. Sustainable Blue Finance Development Process. China Financ. 2022, 23, 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Fang, T. Focus on Blue Finance for Sustainable Ocean Development. China Bank. Ind. 2022, 10, 80–82. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The Ocean Economy in 2030; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, M.J.; Snyder, B. The Five Offshore Drilling Rig Markets. Mar. Policy 2013, 39, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.M.; Barnard, P.; Koh, L.P.; Chapman, C.A.; Altwegg, R.; Garner, T.W.J.; Gompper, M.E.; Gordon, I.J.; Katzner, T.E.; Pettorelli, N. Funding Nature Conservation: Who Pays? Anim. Conserv. 2012, 15, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Current Situation, Challenges and Trends of Marine Economy Development. China Rural. Financ. 2022, 18, 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L. Study on the Current Situation and Strategy of Marine Economy Development in Ningbo City. Chin. Soc. Oceanogr. 2018, 03, 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacic, M.; Perinic, L.; Kercevic, S. Greening the Blue Economy as an Incentive to Sustainable Development of Primorje-Gorski Kotar County. Pomor.-Sci. J. Marit. Res. 2021, 35, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niner, H.J.; Barut, N.C.; Baum, T.; Diz, D.; del Pozo, D.L.; Laing, S.; Lancaster, A.M.S.N.; McQuaid, K.A.; Mendo, T.; Morgera, E.; et al. Issues of Context, Capacity and Scale: Essential Conditions and Missing Links for A Sustainable Blue Economy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 130, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuwung, L.; Croft, F.; Benzaken, D.; Azmi, K.; Goodman, C.; Rambourg, C.; Voyer, M. Global Blue Economy Governance—A Methodological Approach to Investigating Blue Economy Implementation. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katila, J.; Ala-Rami, K.; Repka, S.; Rendon, E.; Torronen, J. Defining and Quantifying the Sea-Based Economy to Support Regional Blue Growth Strategies—Case Gulf of Bothnia. Mar. Policy 2019, 100, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusov, P.; Filatova, T.; Orekhova, N.; Kulik, V.; Chang, S.I.; Lin, G. The Generalization of the Brusov-Filatova-Orekhova. Theory for the Case of Payments of Tax on Profit with Arbitrary Frequency. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howson, P. Building Trust and Equity in Marine Conservation and Fisheries Supply Chain Management with Blockchain. Mar. Policy 2020, 115, 103873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.F.; Caruso, V.; Peterson, E. An Updated Orientation to Marine Conservation Funding Flows. Mar. Policy 2019, 107, 103497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, D.; Michael, K. Government Support to Private Infrastructure Projects in Emerging Markets. In Proceedings of the Managing Government Exposure to Private Infrastructure Projects: Averting a New-Style Debt Crisis, Cartagena, Colombia, 29–30 May 1997; Conference Report. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- EU Commission. Introducing the Sustainable Blue Economic Financing Principles. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/sites/maritimeaffairs/files/introducing-sustainable-blue-economy-finance-principles_en.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Sarda, R.; Pogutz, S.; de Silvio, M.; Allevi, V.; Saputo, A.; Daminelli, R.; Fumagalli, F.; Totaro, L.; Rizzi, G.; Magni, G.; et al. Business for Ocean Sustainability: Early Responses of Ocean Governance in The Private Sector. Ambio 2023, 52, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, Q.; Feng, X.; Liu, C.; Du, Y. A Positive Externality-Based Approach to Regional Rail Transport Government Subsidy Sharing. Transp. Stud. 2022, 8, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, M.R.; Schwarz, A.M.; Wini-Simeon, L. Towards Defining the Blue Economy: Practical Lessons from Pacific Ocean Governance. Mar. Policy 2018, 88, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderklift, M.A.; Herr, D.; Lovelock, C.E.; Murdiyarso, D.; Raw, J.L.; Steven, A.D.L. A Guide to International Climate Mitigation Policy and Finance Frameworks Relevant to the Protection and Restoration of Blue Carbon Ecosystems. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Jiang, Q. The Dual Public-Private Nature of the Platform and Intermediary Role of Synergistic Markets and Governments. Res. Financ. Issues 2022, 10, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.F.; Zhao, D.; Luo, R.J. Evolutionary Game Analysis on Local Governments and Manufacturers’ Behavioral Strategies: Impact of Phasing Out Subsidies for New Energy Vehicles. Energy 2019, 189, 116064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, Y.; He, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, X. Financial Industry in the Blue Economic Zone of Shandong Peninsula: Development Status, Problems and Countermeasures. Econ. Manag. Rev. 2013, 29, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Lee, M. An Analysis of the Participation of Villagers in Rural Governance and Its Stability Based on the Perspective of Evolutionary Game. Agric. Econ. Issues 2020, 4, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuechle, G. Persistence and Heterogeneity in Entrepreneurship: An Evolutionary Game Theoretic Analysis. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J. Analysis of Evolutionary Path of the Game between Government and Marine Industry under Conditions of Incomplete Information. Econ. Forum 2020, 4, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Accelerating Financial Innovation to Help Blue Ocean Strategy. Financ. Dev. Stud. 2011, 10, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonocore, E.; Grande, U.; Franzese, P.P.; Russo, G.F. Trends and Evolution in the Concept of Marine Ecosystem Services: An Overview. Water 2021, 13, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergelova, A.; Angulo-Ruiz, F. The Impact of Government Financial Support on the Performance of New Firms: The Role of Competitive Advantage as An Intermediate Outcome. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2014, 26, 663–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, N.; Wu, H.; Huang, M.; Tanaka, H. Proposing Regulatory-Driven Blue Finance Mechanism for Blue Economy Development. ADBI Working Paper 1157. Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, 2020. Available online: https://www.adb.org/publications/proposingregulatory-driven-blue-finance-mechanism-blue-economy-development (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Ali, O.; Osmanaj, V. The Role of Government Regulations in the Adoption of Cloud Computing: A Case Study of Local Government. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2020, 36, 105396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, M.; Pressey, R.L.; Stoeckl, N. Marine Conservation Finance: The Need for and Scope of An Emerging Field. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2015, 114, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderklift, M.A.; Marcos-Martinez, R.; Butler, J.R.A.; Coleman, M.; Lawrence, A.; Prislan, H.; Steven, A.D.L.; Thomas, S. Constraints and Opportunities for Market-Based Finance for the Restoration and Protection of Blue Carbon Ecosystems. Mar. Policy 2019, 107, 103429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, J. Fixing Fictions through Blended Finance: The Entrepreneurial Ensemble and Risk Interpretation in the Blue Economy. Geoforum 2021, 120, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q. Institutional Pathways for Renewable Energy Development in the Context of the Green Energy Revolution. Zhongzhou J. 2019, 7, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayyedi, P.; Mason, J. Cost-Utility and Cost-Benefit Analyses: How did We Get Here and Where are We Going? Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2004, 16, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieß, C.K. Efficiency Analysis of Early Education and Care Programmes—The Example of Cost-Benefit Analysis. Z. Fur. Erzieh. 2013, 16, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, B.T. Cost-inclusive evaluation: A Banquet of Approaches for including Costs, Benefits, and Cost-Effectiveness and Cost-Benefit Analyses in Your Next Evaluation. Eval. Prog. Plan. 2009, 32, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.F. Financial Risk and Financial Early Warning of Marine Enterprises Based on Marine Economy. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. The Role of Government in the Development of Strategic New Industries. China Sci. Technol. Forum. 2011, 1, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, X. An Empirical Study on the Impact of Government Subsidies on Corporate Performance of Enterprises in the Marine-Related Industries. Intell. Cities 2017, 3, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankpa, J.K.; Merhout, J.W. Exploring the Effect of Digital Investment on IT Innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wei, H.; Xie, L. Mitigating Product Quality Risk under External Financial Pressure: Inspection, Insurance, and Cash/Collateralized Loan. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Wu, H.; Yu, Y. Investment-Related Pressure and Audit Risk. Audit.-A J. Pract. Theo. 2017, 36, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Sapra, H. Auditor Conservation and Investment Efficiency. Account. Rev. 2009, 84, 1933–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, D. The Impact of Government Subsidies on the Operating Performance of Listed Marine Fisheries Companies. Mar. Dev. Manag. 2021, 38, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Shi, D. Study on the Relationship between Fiscal Subsidies and Business Performance of Listed Agricultural Enterprises. Green Acc. 2012, 6, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, X.; Xu, S.; Shi, D.; Liu, F. Pricing Decisions and Subsidy Preference of Government with Traditional and Green Products. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2020, 11, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Graham, M.; Foster, E.A. Improving Local Government Resilience: Highlighting the Role of Internal Resources in Crisis Management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Harold Groves, Wisconsin Institutionalism, and Postwar Public Finance. J. Econ. Issues 2015, 49, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zheng, H.Y.; Liang, W.H. How to Enhance Government Trust and Social Cohesion: Evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmelkov, A. Public Finance: Scope and Content. Financ. Credit. Act.-Probl. Theory Pract. 2018, 4, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lee, C. Stability of Agricultural Channel Relationships between “Farmers and Leading Enterprises”—An Analysis Based on An Evolutionary Game Perspective. Financ. Trade Econ. 2008, 2, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, C.; Schossau, J.; Hintze, A. The Reasonable Effectiveness of Agent-Based Simulations in Evolutionary Game Theory: Reply to Comments on “Evolutionary Game Theory Using Agent-Based Methods”. Phys. Life Rev. 2016, 19, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.; Tang, Y.; Xiong, J.; Wang, W.J.; Zhang, Y.C. Dynamics of Cooperation in Minority Games in Alliance Networks. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D. On Economic Applications of Evolutionary Game Theory. J. Evol. Econ. 1998, 8, 15–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Luo, X. Analysis on Game Evolution of Latecomer Prefabricated Building Firm from the Perspective of Population Ecology. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 5529–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wei, X.; Liu, C. Tripartite Evolutionary Game Analysis of Shared Manufacturing by Manufacturing Companies under Government Regulation Mechanism. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 2022, 7706727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, A.; Yao, Y.; Chen, H. University-Industry Collaborative Innovation Evolutionary Game and Simulation Research: The Agent Coupling and Group Size View. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 68, 1406–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defez, E.; Jodar, L.; Law, A. Jacobi Matrix Differential Equation, Polynomial Solutions, and Their Properties. Comput. Math. Appl. 2004, 48, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, I.; Golinskii, L. Discrete Spectrum for Complex Perturbations of Periodic Jacobi Matrices. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 2005, 11, 1185–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterbach, R.; Opfer, G. The Jacobi Matrix for Functions in Noncommutative Algebras. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebras 2014, 24, 1059–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Bebiano, N.; Chen, G. A Reduction Algorithm for Reconstructing Periodic Jacobi Matrices in Minkowski Spaces. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L. Exploration of Land-Sea Integrated Planning and Design Methods under the Orientation of Resilient City—An Example of Detailed Planning of Shenzhen Ocean New City. Spat. Gov. Qual. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trequattrini, R.; Lardo, A.; Cuozzo, B.; Manfredi, S. Intangible Assets Management and Digital Transformation: Evidence from Intellectual Property Rights-Intensive Industries. Meditari Acc. Res. 2022, 30, 989–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Bowman, G.; Mervine, E.; Southam, C. Embedding Environment and Sustainability into Corporate Financial Decision-Making. Acc. Financ. 2020, 60, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, T.J.; Williams, E.F. Multiple Revenue Streams from Your Existing and New Practice Opportunities: Focusing on Core Values Versus Distractions. Facial Plast. Surg. 2010, 26, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Deng, C.; Chen, H. Trust in Government, Social Determinants, and Resource Distribution after a Catastrophic Typhoon. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2021, 22, 04020050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liang, S. Research on the Governance Mechanism of Internet Information Ecosystem Based on Evolutionary Game. Contemp. Econ. Sci. 2022, 45, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen Despina, F.; Vestvik Rolf, A. The Cost of Saving Our Ocean—Estimating the Funding Gap of Sustainable Development Goal 14. Mar. Policy 2020, 112, 103783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, L.E. An Open and Scalable Method for Spatial Measurement of Blue Economies. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhou, Z. Blue Finance—A Booster for the Development of the Blue Economic Zone on the Shandong Peninsula. Mod. Commer. 2011, 11, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Government Intervention Methods | Monetary Incentives | Non-Monetary Incentives |

| Subsidies | Official Recognition | |

| Tax Breaks | Media Publicity | |

| … | … |

| Game Players | ||

|---|---|---|

| Private Sector | Chinese Government | |

| Equilibrium | ||

|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium | Stability | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstable point | |||

| Unstable point | |||

| Meaningless |

| Parameter | Partial Derivatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Parameters and Parameter Combinations | Player | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Chinese government | Government cost of subsiding PSIMS. | |

| Chinese government | The difference in governmental revenue from PSIMS with and without governmental involvement. | |

| Private sector | Regulations introduced by the Chinese government have decreased the uncertainty of investment in the maritime sector, and the intangible advantages achieved by enterprises are recorded. | |

| Private sector | The difference in private sector revenue with and without governmental involvement. | |

| Private sector | The difference between the revenue gained by enterprises investing in marine industry and non-marine industry without governmental intervention. |

| Factor | Governmental Intervention | Strategy Selection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Private Sector | Chinese Government | {Invest, Intervene} Strategy | |||

| “Intervene” Strategy | “Invest” Strategy | ||||

| Different Initial Probabilities | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Parameters | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Yes | Yes | - | Yes | ||

| Yes | - | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | - | Yes | Yes | ||

| No | - | Yes | Yes | ||

| Yes | - | - | - | ||

| No | - | - | - | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Huang, W. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Governmental Intervention in the Sustainable Mechanism of China’s Blue Finance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097117

Chen Z, Huang W. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Governmental Intervention in the Sustainable Mechanism of China’s Blue Finance. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097117

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zhihan, and Weilun Huang. 2023. "Evolutionary Game Analysis of Governmental Intervention in the Sustainable Mechanism of China’s Blue Finance" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097117

APA StyleChen, Z., & Huang, W. (2023). Evolutionary Game Analysis of Governmental Intervention in the Sustainable Mechanism of China’s Blue Finance. Sustainability, 15(9), 7117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097117