Consumption Culture and Critical Sustainability Discourses: Voices from the Global South

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Neocolonial Anti-Sustainable Market Rhetoric, and the Need for Critical Sustainability Discourse

‘Land of coal and iron! land of gold! land of cotton, sugar, rice!/Land of wheat, beef, pork! land of wood and hemp! Land of the apple and the grape!/Land of the pastoral plains, the grass-fields of the world! land of those sweet-air’d interminable plateaus!/Land of the herd, the garden, the healthy house of adobie!’(Walt Whitman, ’Starting from Paumanok’, as cited in [38] (p. 294))

‘Hunger is intensifying due to many interacting factors: as COVID-19 assails the Amazon; Jair Bolsonaro’s government shreds once effective social welfare programs and cheerleads forest destruction; and climate change-driven extreme floods and droughts are on the upswing. Experts warn that these circumstances intensify threats to food security for the poor in remote riverine communities’[42] (n.pg)

Sustainable Consumption as Identity Politics at the Margin

3. Research Objectives and Research Questions

- How does the traditional consumer culture evoke a counter discourse of sustainability, beyond the normalized globalized version of the same?

- How does the traditional sustainable consumption culture and its everydayness of politics help build agency and community identity?

4. Research Method

5. Narrative Performances

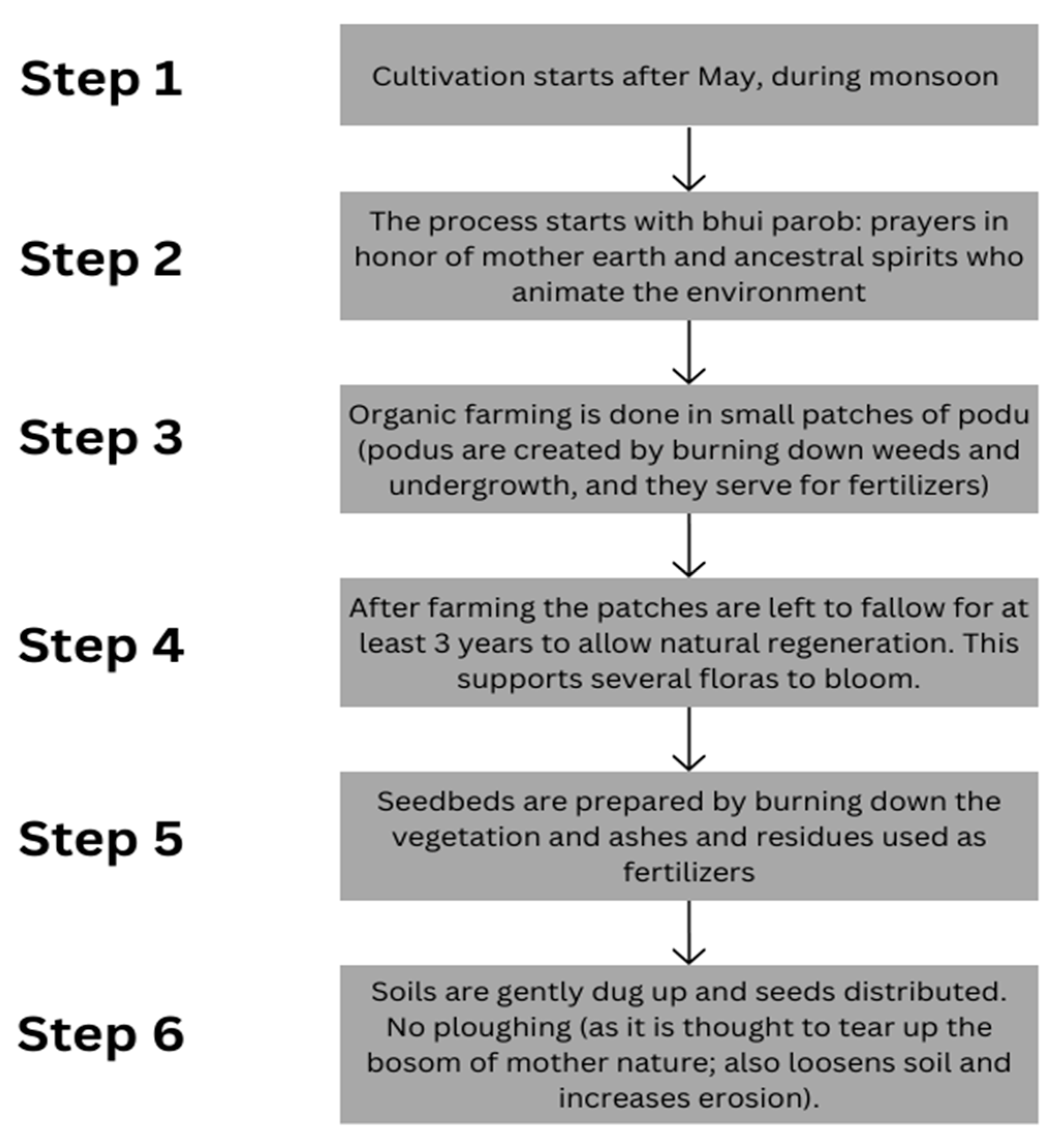

5.1. Bondas and Sustainable Farming

‘We will not leave our village!Nor our forests!Nor our mother-earth!We will not give up our fight!They build lands, drowned villages, and built factoriesThey cut down forests, dug out mines, and built sanctuaries.…Oh God of Development pray tell us, how to save our lives?…You may drink your colas and bottled BisleriesHow shall we quench our thirst with such polluted water?Were our ancestors fools that they conserved the forests?Made the land so green, made rivers flow like honey?Your greed has charred the land and looted its greenery!…We will not give up our fight!’

5.2. Patachitrakars, Sustainable Counter Episteme of Traditional Aesthetics, and Rethinking Modernity

‘[…] they needed to innovate for their performances to remain fresh and relevant to contemporary society and the issues that confronted it. The Patuas thus developed a new genre of a song called samajik gaan, or “social song”, which did not replace pauranik gaan, but supplemented it’

‘Today the means of representing cultural identity includes the whole range of plastic and visual arts, film and television and, crucially, strategies for consuming these products. Hence, trans-formation, which describes one way of viewing cultural identity, also describes the strategic process by which cultural identity is represented. By taking hold of the means of representation, colonized peoples throughout the world have appropriated and transformed those processes into culturally appropriate vehicles. It is this struggle over representation which articulates most clearly the material basis, the constructiveness and dialogic energy of the ‘post-colonial imagination’

‘During the lockdown I have done many workshop programmes online and earned from it as well. Previously people would come to our village to buy products and attend workshop but now I can do all these online. We were unaware about online marketing before, HIPAMS has taught us to do that. We have learnt that business can also be done online by posting pictures of our product’[93]

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Future Research and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fleurbaey, M.; Kartha, S.; Bolwig, S.; Chee, Y.L.; Chen, Y.; Corbera, E.; Lecocq, F.; Lutz, W.; Muylaert, M.S.; Norgaard, R.B.; et al. Sustainable Development and Equity. In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 283–350. [Google Scholar]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate Social Responsibility and Resource-Based Perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The effect of CSR on Corporate Image, Customer Citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Greening, D.W. Corporate Social Performance and Organizational Attractiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuo, J. A study of strategic CSR and BOP business practice. In CSR, Sustainability, and Leadership; Eweje, G., Bathurst, R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B.; Ketchen, D.J.; Wright, M. The future of resource-based theory: Revitalization or decline? J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciszewska-Mlinarič, M.; Wasowska, A. Resource-Based View (RBV). In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management; Vodosek, M., den Hartog, D., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2015; Volume VI, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, J.; Prothero, A. Sustainable Consumption: Consumption, Consumers and the Commodity Discourse. Consum. Markets Cult. 2003, 6, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Prothero, A. Green Consumption–Life-politics, Risk and Contradictions. J. Consum. Cult. 2008, 8, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tadajewski, M.K.; Brownlie, D. Critical Marketing: A Limit Attitude. In Critical Marketing: Contemporary Issues in Marketing; Tadajewski, M., Brownlie, D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, F. Critical Sustainability Studies: A Holistic and Visionary Conception of Socio-Ecological Conscientization. J. Sustain. Educ. 2017, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, J.; Cachelin, A. Critical Sustainability: Incorporating Critical Theories into Contested Sustainability. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2018, 8, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Moulton, A.A.; Van Sant, L.; Williams, B. Anthropocene, Capitalocene, … Plantationocene? A Manifesto for Ecological Justice in an Age of Global Crises. Geogr. Compass 2019, 13, e12438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alier, J. The Environmentalism of the Poor: A Study of Ecological Conflicts and Valuation; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman, J. Introducing just Sustainabilities: Policy, Planning, and Pract; Zed Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, C. Play a Game, Save the Planet: Gamification as a way to Promote Green Consumption. In The Business of Gamification: A Critical Analysis; Dymek, M., Zackariasson, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 144–160. [Google Scholar]

- Denegri-Knott, J.; Nixon, E.; Abraham, K. Politicizing the study of sustainable living practices. Consum. Market Cult. 2018, 21, 554–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, M.; Rosa, J.A. Understanding subsistence marketplaces: Toward sustainable consumption and commerce for a better world. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.; Shaw, G. Citizens, consumers and sustainability: Re(framing) environmental practice in an age of climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, N.; Rudnak, I.; Ymeri, P.; Fogarassy, C. The role of cultural factors in sustainable food consumption—An investigation of the consumption habits among international students in Hungry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Malloy, T.H. Minority environmentalism and eco-nationalism in the Baltics: Green citizenship in the making? J. Balt. Stud. 2009, 40, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, C.; Michaels, A. Vernacular heritage as urban place-making. Activities and positions in the reconstruction of monuments after the Gorkha earthquake in Nepal, 2015–2020: The case of Patan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, B.Y.; Albinsson, P.A.; Chaudhury, S.R. Online Consumer Activism 2.5: Youth at the Forefront of the Global Climate Crisis. In The Routledge Handbook of Digital Consumption; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 461–474. [Google Scholar]

- Raman, R.K. Environmental ethics, livelihood, and human rights: Subaltern driven cosmopolitanism? Nat. Cult. 2008, 3, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldavanova, A. Sustainability, ethics, and aesthetics. Int. J. Sustain. Policy Pract. 2013, 8, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Merrill, L.; Kitson, L.; Beaton, C.; Sharma, S.; Zinecker, A.; Chowdhury, T.T.; Singh, C.; Sharma, A.; Ibezim-Ohaeri, V.; Adeyinka, T. Gender and fossil fuel subsidy reform: Findings from and recommendations for Bangladesh, India, and Nigeria. Energia: International Network on Gender and Sustainable Energy. 2019. Available online: https://www.energia.org/cm2/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/RA4_Gender-and-fossil-fuel-subsidy-reform_without-Annex-2.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Brown, T. Farmers, Subalterns, and Activists: Social Politics of Sustainable Agriculture in India; Cambridge University Press: New Delhi, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- D’Urso, D. Memory as Material of the Project of Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, P.J.; Stoermer, E.F. The Anthropocene. IGBP Newsl. 2000, 41, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S.L.; Maslin, M.A. Defining the Anthropocene. Nature 2015, 519, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.; Hogarth, M.; Sturm, S.; Martin, B. Colonization of all forms. Educ. Philos. Theory 2022, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appadurai, A. The Social life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Luxemburg, R. Rosa Luxemburg, Selected Political and Literary Writings; Merlin Press: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A. Demarketization and Subaltern Politics: Views from India. In Disruptions for a Better World: Consumer Culture Theory Conference; Oregon State University, College of Business: Oregon, OR, USA, 2022; p. 56. Available online: https://cctc2022.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/CCT2022-PROGRAM-final-23jun22.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Smith, M. Against Ecological Sovereignty: Agamben, Politics, and Globalization. Environ. Politics 2009, 18, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri-Dutt, K. The Coal Nation: Histories, Ecologies and Politics of Coal in India; Ashgate Publishing Company: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, T.; Lahiri-Dutt, K. World Bank, Coal and Indigenous Peoples: Lessons from Parej East, Jharkhand. In The Coal Nation: Histories, Ecologies and Politics of Coal in India; Lahiri-Dutt, K., Ed.; Ashgate: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, A.W. Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Korff, J. Aboriginal Alcohol Consumption. Creative Spirits. 2022. Available online: https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/health/aboriginal-alcohol-consumption (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Kahn, M.W.; Hunter, E.; Heather, N.; Tebbutt, J. Australian Aborigines and Alcohol: A Review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1991, 10, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.C.; Baeza, A.; Codeço, C.T.; Cucunubá, Z.M.; Dal’Asta, A.P.; De Leo, G.A.; Dobson, A.P.; Carrasco-Escobar, G.; Lana, R.M.; Lowe, R.; et al. Development, Environmental Degradation, and Disease Spread in Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hanbury, S. Amazon Poor Go Hungry as Brazil Slashes Social Safety Net, Cuts Forecasts: Study. Mongaby. 2020. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/2020/06/amazon-poor-go-hungry-as-brazil-slashes-social-safety-net-cuts-forests-study/ (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Langan, M. Neo-Colonialism and the Poverty of ‘Development’ in Africa. In The UN Sustainable Development Goals and Neo-Colonialism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Chapter 7; pp. 177–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Global Compact. SDG Compass: UN Executive Summ; United Nations Global Compact: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P.J.; Reitzes, D.C. An identity theory approach to commitment. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1991, 54, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.; Beers, P.J.; van Mierlo, B. Identity in sustainability transitions: The crucial role of landscape in the Green Heart. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2022, 42, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Laroche, M. Acculturation to the global consumer culture: Scale development and research paradigm. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindridge, A.; Peñaloza, L.; Worlu, O. Agency and empowerment in consumption in relation to a patriarchal bargain: The case of Nigerian immigrant women in UK. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 1652–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ger, G. Localizing in the global village: Local firms competing in global markets. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1999, 41, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Campbell, J.L. Institutional Change and Globalization; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A. Possibilities through ‘Strategic Essentialism’: Adani TNC and Protest and Negotiation Discourses in Australia. In Transnational Spaces of India and Australia; Sharrad, P., Bandyopadhyay, D.N., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cock, J. The climate crisis and a ‘just transition’ in South Africa: An eco-feminist-socialist perspective. In The Climate Crisis: South African and Global Democratic Eco-Socialist Alternatives; Satgar, V., Ed.; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2018; pp. 210–230. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, H.; Jacobs, J. Qualitative Sociology: A method to the Madness; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.J.; Locander, W.B.; Pollio, H.R. Putting consumer experience back into consumer research: The philosophy and method of existential-phenomenology. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humayun, M.; Russell, W. Belk. Satoshi is Dead. Long Live Satoshi: The Curious Case of Bitcoin’s Creator. In Consumer Culture Theory; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; Volume 19, pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The Semiotics of Consumption: Interpreting Symbolic Consumer Behavior in Popular Culture and Works of Art; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2012; Volume 110. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A. How Odisha’s Malkangiri Is Improving Tribal Literacy Rate. NITI Aayog. 2020. Available online: https://www.niti.gov.in/how-odishas-malkangiri-improving-tribal-literacy-rates (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Ota, A.B. Review of Tribal Sub-Plan Approach in Odisha: Study of Provision, Implementation and Outcome; Scheduled Casts and Scheduled Tribes Research and Training Institute (SCSTRTI): Bhubaneswar, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, D. Bonda Tribe and Higher education: A Case Study in Odisha. Edu. Quest Int. J. Edu. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2022, 13, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A. In Odisha, an Adivasi Community Is Using Traditional Farming to Fight Climate Change. Scroll. In. 2021. Available online: https://scroll.in/article/998817/in-odisha-an-adivasi-community-is-using-traditional-farming-to-fight-climate-change (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Franco, F.M.; Narasimhan, D. Ethnobotany of Kondh, Poraja, Gadaba and Bonda of the Koraput Region of Odisha; D.K. Printworld: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, M. This Odisha Tribe Grows 20 Crop Varieties. DownToEarth. 2019. Available online: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agriculture/this-odisha-tribe-grows-20-crop-varieties-without-jeopardising-biodiversity-65738 (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Patra, D. Lord Patakhanda of the Bonda Tribes. Odisha Rev. 2017, 74, 67–71. Available online: https://magazines.odisha.gov.in/Orissareview/2017/November/engpdf/67-71.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- De, D. A History of Adivasi Women in Post-Independence Eastern India: The Margin of the Marginals; Sage: New Delhi, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Singhdeo, S. Bonda Tribal Women’s Resistance to Climate Change: Traditional Knowledge, Gender, and Environment Conservation. FII: Feminism in India. 2022. Available online: https://feminisminindia.com/2022/07/20/bonda-tribal-women-climate-change-traditional-knowledge-gender-environment/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Pati, R.N.; Dash, J. Tribal and Indigenous People of India: Problems and Prospects; A.P.H. Publishing Corporation: New Delhi, India, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, S.B.; Child, J. The role of corporations in addressing non-market institutional voids during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of an emerging economy. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2023, 6, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varman, R.; Belk, R.W. Nationalism and Ideology in an Anticonsumption Movement. J. Consum. Res. 2009, 36, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, C.G.; Plouffe, C.R.; Peters, C. Anti-commercial consumer rebellion: Conceptualisation and measurement. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Market. 2005, 14, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, H. Anti-consumption discourses and consumer-resistant identities. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Daniele, D.; Corciolani, M. Collective forms of resistance: The transformative power of moderate communities. Int. J. Market Res. 2008, 50, 757–775. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkonen, I.; Bajde, D. Happy Festivas! parody as playful consumer resistance. Consum. Markets Cult. 2012, 16, 311–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornescu, V.; Adam, C.R. The consumer resistance behavior towards innovation. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2013, 6, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saren, M.; Parsons, E.; Goulding, C. Dimensions of marketplace exclusion: Representation, resistances and responses. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2019, 22, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, H. Consumer identity and moral obligations in non-plastic bag consumption: A dialectical perspective. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2006, 30, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Autio, M.; Heiskanen, E.; Heinonen, V. Narratives of ‘green’ consumers--the antihero, the environmental hero and the anarchist. J. Consum. Behav. 2009, 8, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, H. Custodian behavior: A material expression of anti-consumerism. Consum. Markets Cult. 2010, 13, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shankar, A.; Cherrier, H.; Canniford, R. Consumer empowerment: A Foucauldian interpretation. Eur. J. Market. 2006, 40, 1013–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thompson, C. Caring Consumers: Gendered Consumption Meanings and the Juggling Lifestyle. J. Consum. Res. 1996, 22, 388–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.; Arnould, E. Liquid Relationship to Possessions. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 510–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chitrakar, G. An Interview with Gurupada Chitrakar. The Living Art of Naya Singer Painters: IIT Kharaghpur. 2021. Available online: http://www.dlb.iitkgp.ac.in/gurupada-chitrakar/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Chakraborty, U. Patachitra: Una forma artistica e narrativa Indiana, locale e globale. Hermes J. Commun. 2017, 9, 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Patachitra, B. Rural Craft Hub Pingla: Paschim Medinipur 2020. Patachitra: Narrative Visuals. Available online: https://bengalpatachitra.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Patachitra-Brochure.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Zanatta, M.; Roy, A.G. Facing the pandemic: A perspective on patachitra artists of West Bengal. Arts. 2017, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korom, F.J. Social Change as Depicted in the Folklore of Bengali Patuas: A Pictorial Essay. In Social Change and Folklore; Mahmud, F., Khatun, S., Eds.; Bangla Academy: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2017; pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Korom, F.J. Village of Painters: Narrative Scrolls from West Bengal; Museum of New Mexico Press: Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft, B. Post-colonial Transformation; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Awada, N. How Health and Poverty in India Overlap. The Borgen Project. 2022. Available online: https://borgenproject.org/health-and-poverty-in-india/ (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Chandola, B. Exploring India’s Digital Divide. Observation Research Foundation. 2022. Available online: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/exploring-indias-digital-divide/ (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Patra, A. Traditional Art Goes Digital in Times of Crisis. Heritage-Sensitive Intellectual Property & Marketing Strategy. 2020. Available online: https://hipamsindia.org/traditional-art-goes-digital-in-times-of-crisis/ (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- HIPMAS. Patachitra Case Study: Safeguarding Heritage Art and Sustaining Livelihoods. The HIPMAS Case Studies. 2021. Available online: https://hipamsindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/HIPAMS-India-Case-Studies.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Pandey, J.M. Pingala patachitra for New Town COVID Awareness. The Times of India. 2020. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolkata/pingla-patachitra-for-new-town-cov-awareness/articleshow/79357830.cms (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Chitrakar, S. Patachitra on HIV or AIDS Awareness. Banglanatak. Com. 2006. Available online: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/patachitra-on-hiv-aids-awareness-swarna-chitrakar/6wGRTPBRV6O3eA?hl=en (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Chitrakar, M. Patachitra on Environment Conservation. Banglanatok. Com. 2018. Available online: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/patachitra-on-environment-conservation-mamoni-chitrakar/3AFXkMw6xkgerQ?hl=en (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Chitrakar, S. Patachitra on Gender Equality. Banglanatok. Com. 2018. Available online: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/patachitra-on-gender-equality-swarna-chitrakar/qQEVwLAZiSJPTA?hl=en (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Fairhead, J.; Leach, M.; Scoones, I. Green Grabbing: A New Appropriation of Nature? J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 237–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Comberti, C.; Thornton, T.; Korodimou, M. Addressing Indigenous Peoples’ Marginalisation at International Climate Negotiations: Adaptation and Resilience at the Margins; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabus, N. Traditional Knowledge. In Biodiversity and Nature Protection Law; Morgera, E., Razzaque, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Gloucester, UK, 2017; Volume III, pp. 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanaizu, S. Green Revolution of Neocolonialism: Revising Africa’s Land Grab, Harvard International Review. 2019. Available online: https://hir.harvard.edu/green-revolution-or-neocolonialism-revisiting-africas-land-grab/ (accessed on 19 November 2022).

- Beck, S.; Forsyth, T. Who gets to imagine transformative change? Participation and representation in biodiversity assessments. Environ. Conserv. 2020, 47, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram-Hanssen, I.; Schafenacker, N.; Bentz, J. Decolonizing transformations through ‘right relations. ’ Sustain. Sci. 2021, 17, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odijie, M.E. Unintentional neo-colonialism? Three generations of trade and international relationship between EU and West Africa. J. Eur. Integr. 2022, 44, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldmann, J.; Manica, A.; Burgess, N.D.; Balmford, A. A Global-Level Assessment of the Effectiveness of Protected Areas at Resisting Anthropogenic Pressures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23209–23215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niheu, K. Indigenous resistance in the era of climate change crisis. Radic. Hist. Rev. 2019, 133, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassatelli, R. Consumer culture, sustainability, and a new vision of consumer sovereignty. Sociol. Rural. J. Eur. Soc. Rural Sociol. 2015, 55, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Chaudhuri, H.R. Pandemics and consumer well-being from the Global South. J. Consum. Aff. 2022, 56, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Das, A.; Albinsson, P.A. Consumption Culture and Critical Sustainability Discourses: Voices from the Global South. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7719. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097719

Das A, Albinsson PA. Consumption Culture and Critical Sustainability Discourses: Voices from the Global South. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7719. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097719

Chicago/Turabian StyleDas, Arindam, and Pia A. Albinsson. 2023. "Consumption Culture and Critical Sustainability Discourses: Voices from the Global South" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7719. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097719

APA StyleDas, A., & Albinsson, P. A. (2023). Consumption Culture and Critical Sustainability Discourses: Voices from the Global South. Sustainability, 15(9), 7719. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097719