Housing Affordability Risk and Tourism Gentrification in Kyoto City

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Analysis Flow

2.2. Accommodation List

2.3. Real Estate Dataset

3. Results

3.1. Locations of Accommodations and Houses

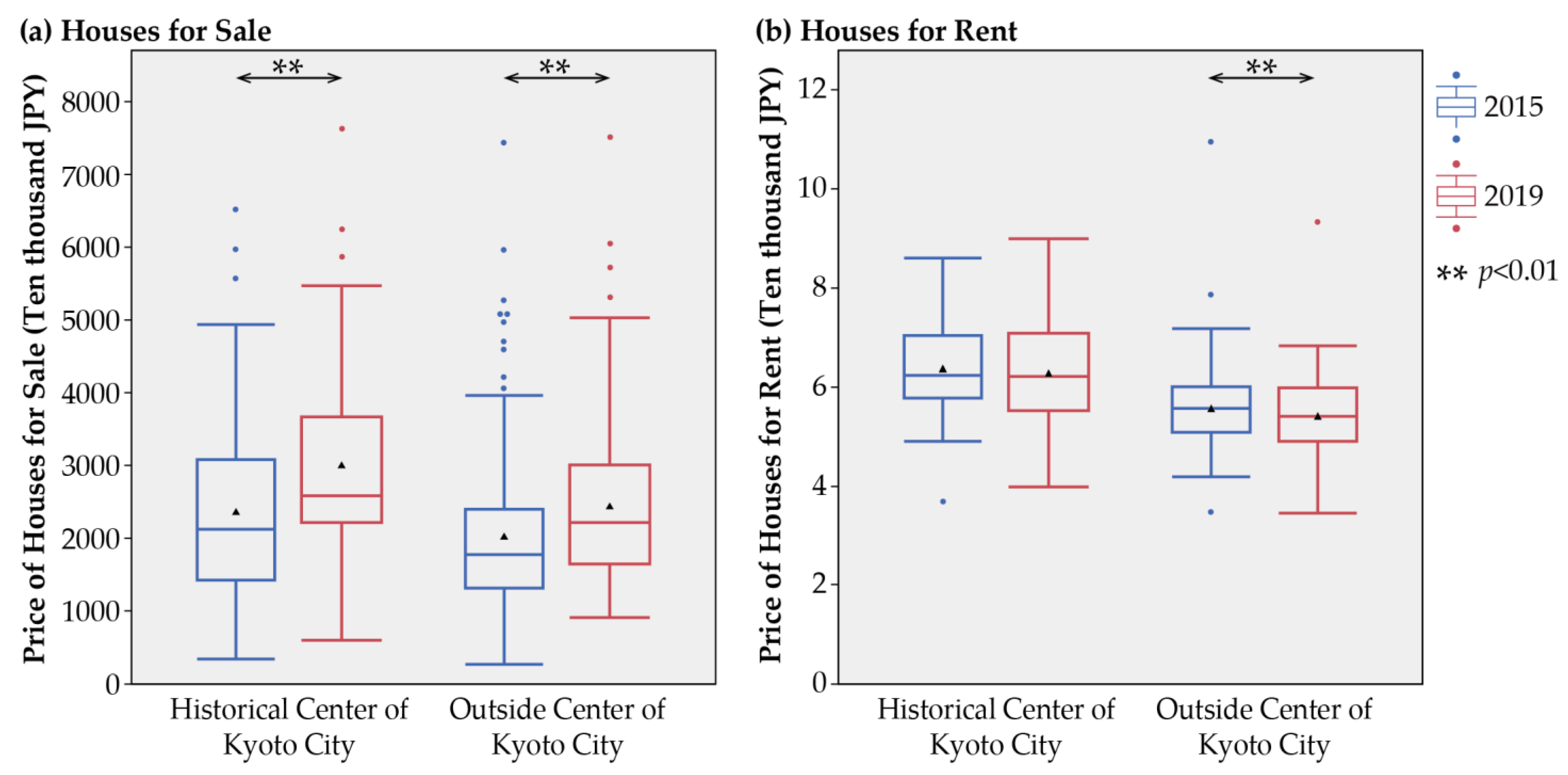

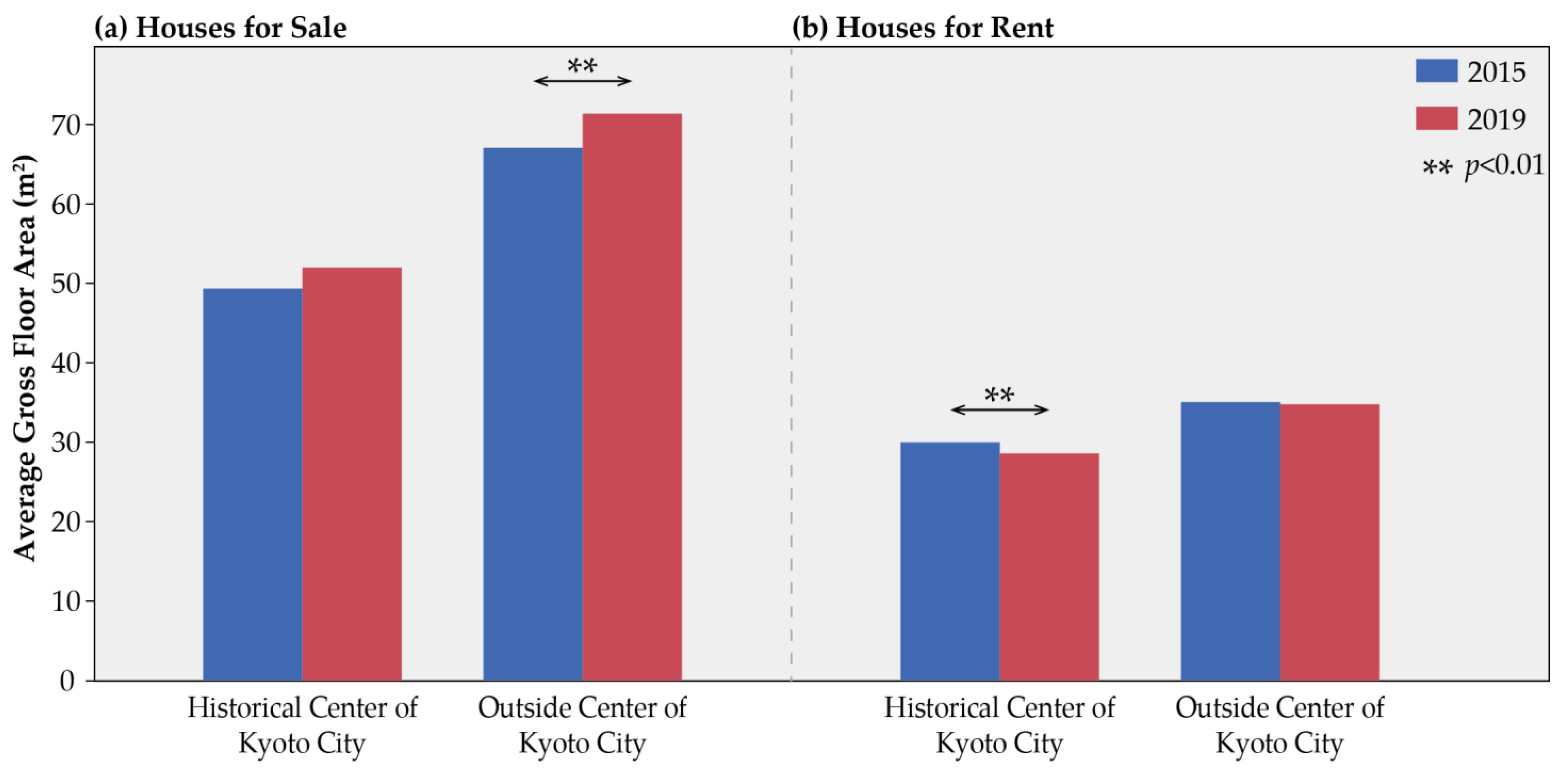

3.2. Changes in Houses from 2015 to 2019

3.3. The Relationship between Accommodation and Housing Price

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Tourism Organization. ‘Overtourism’?—Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions, Executive Summary; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Muler Gonzalez, V.; Coromina, L.; Galí, N. Overtourism: Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Impact as an Indicator of Resident Social Carrying Capacity—Case Study of a Spanish Heritage Town. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is Overtourism Overused? Understanding the Impact of Tourism in a City Context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.R.; Kruczek, Z.; Walas, B. The Attitude of Tourist Destination Residents towards the Effects of Overtourism-Kraków Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.F. Tourism Gentrification: The Case of New Orleans’ Vieux Carre (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestegás, I.; Seixas, J.; Lois-González, R.-C. Commodifying Lisbon: A Study on the Spatial Concentration of Short-Term Rentals. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A.; Gago, A. Airbnb, Buy-to-Let Investment and Tourism-Driven Displacement: A Case Study in Lisbon. Environ. Plan A 2021, 53, 1671–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.; Oliver, C.; Nost, E. Short-Term Rentals as Digitally-Mediated Tourism Gentrification: Impacts on Housing in New Orleans. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 24, 954–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigler, T.; Wachsmuth, D. New Directions in Transnational Gentrification: Tourism-Led, State-Led and Lifestyle-Led Urban Transformations. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3190–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R.; Kato, H.; Matsushita, D. Population Decline and Urban Transformation by Tourism Gentrification in Kyoto City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A.; Lopez-Gay, A. Transnational Gentrification, Tourism and the Formation of ‘Foreign Only’ Enclaves in Barcelona. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3025–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gay, A.; Cocola-Gant, A.; Russo, A.P. Urban Tourism and Population Change: Gentrification in the Age of Mobilities. Popul. Space Place 2021, 27, e2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parralejo, J.-J.; Díaz-Parra, I. Gentrification and Touristification in the Central Urban Areas of Seville and Cádiz. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jover, J.; Díaz-Parra, I. Who Is the City for? Overtourism, Lifestyle Migration and Social Sustainability. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 24, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A. Place-Based Displacement: Touristification and Neighborhood Change. Geoforum 2023, 138, 103665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardura Urquiaga, A.; Lorente-Riverola, I.; Ruiz Sanchez, J. Platform-Mediated Short-Term Rentals and Gentrification in Madrid. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3095–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, J.M. The Dispute over Tourist Cities. Tourism Gentrification in the Historic Centre of Palma (Majorca, Spain). Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisdale, S. Displacement by Disruption: Short-Term Rentals and the Political Economy of “Belonging Anywhere” in Toronto. Urban Geogr. 2021, 42, 654–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübscher, M. Megaprojects, Gentrification, and Tourism. A Systematic Review on Intertwined Phenomena. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jover, J.; Díaz-Parra, I. Gentrification, Transnational Gentrification and Touristification in Seville, Spain. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3044–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieri, D.S. Housing Affordability. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 2971–2975. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, M.; Kato, H. Housing Affordability of Private Rental Apartments According to Room Type in Osaka Prefecture. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulliner, E.; Maliene, V. An Analysis of Professional Perceptions of Criteria Contributing to Sustainable Housing Affordability. Sustainability 2014, 7, 248–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Morales, J.-G.; Checa-Olivas, M.; Cano-Guervos, R. Impact of Evictions and Tourist Apartments on the Residential Rental Market in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, A.M.; Lobão, J. The Effects of Tourism on Housing Prices: Applying a Difference-in-Differences Methodology to the Portuguese Market. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2022, 15, 762–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumka, H.J. Neighborhood Revitalization and Displacement A Review of the Evidence. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1979, 45, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur, J.J. The Politics of Gentrification. Urban Aff. Rev. 2002, 37, 780–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoto City Government Landscape of Kyoto. Chapter 2: The History of Landscape Formation and Town Development in Kyoto. Available online: https://www.city.kyoto.lg.jp/tokei/cmsfiles/contents/0000281/281300/2shou.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- UNESCO. Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto (Kyoto, Uji and Otsu Cities). Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/688/ (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Kyoto City Government Landscape of Kyoto. Chapter 3 Conservation, Revitalization and Creation of Kyoto Landscape. Available online: https://www.city.kyoto.lg.jp/tokei/cmsfiles/contents/0000281/281300/3shou.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Diplomatic Bluebook 2019. Available online: https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/other/bluebook/2019/html/chapter4/c040101.html (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Kato, H.; Takizawa, A. Population Decline through Tourism Gentrification Caused by Accommodation in Kyoto City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H. Residents’ Evaluations of the Tourism Gentrification Caused by Guesthouses in the Central Area of Kyoto City: A Case Study of Shutoku District in Kyoto City. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Chennai, India, 16–17 September 2020; Volume 960. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, H. Process of Developing Community-Based Guidelines in Response to Tourism Gentrification Caused by Simple Accommodations: A Case Study of the Shutoku District in Kyoto City. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2574, 160003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chapple, K.; Cao, M.; Dennett, A.; Smith, D. Visualising Urban Gentrification and Displacement in Greater London. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2020, 52, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-García, F.; Cortés-Macías, R.; Parzych, K. Tourism Impacts, Tourism-Phobia and Gentrification in Historic Centers: The Cases of Málaga (Spain) and Gdansk (Poland). Sustainability 2021, 13, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoto City Library of Historical Documents. Neighborhood Revision and Elementary School. Available online: https://www2.city.kyoto.lg.jp/somu/rekishi/fm/nenpyou/pdffile/toshi26.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2023). (In Japanese).

- Japanese Law Translation. Hotel Business Act. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/ja/laws/view/3272 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Japanese Law Translation. Private Lodging Business Act. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/ja/laws/view/4402 (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Kyoto City Government. Change in Number of Accommodations. Available online: www.city.kyoto.lg.jp/hokenfukushi/cmsfiles/contents/0000193/193116/202310suii.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2023). (In Japanese).

- Kyoto City List of Licensed Accommodations under Ryokan Business Law: Kyoto City Open Data. Available online: https://data.city.kyoto.lg.jp/dataset/00039/ (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Japanese).

- Kyoto City Official Website. Concerning the Use of Minpaku Accommodations as Well as the Offering of Minpaku Services. Available online: https://www.city.kyoto.lg.jp/hokenfukushi/page/0000194935.html (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Center for Spatial Information Science at the University of Tokyo Geocoding Service for CSV Formatted File on WWW. Available online: https://geocode.csis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/geocode-cgi/geocode.cgi?action=start (accessed on 30 July 2023). (In Japanese).

- At Home Co., Ltd. At Home Dataset. Informatics Research Data Repository. National Institute of Informatics. (Dataset). 2020. Available online: https://dsc.repo.nii.ac.jp/?action=pages_view_main&active_action=repository_view_main_item_detail&item_id=4333&item_no=1&page_id=13&block_id=21 (accessed on 28 November 2023). (In Japanese).

- National Institute of Informatics. At Home Dataset. Available online: https://www.nii.ac.jp/dsc/idr/athome/ (accessed on 30 July 2023). (In Japanese).

- Kato, H.; Takizawa, A. Which Residential Clusters of Walkability Affect Future Population from the Perspective of Real Estate Prices in the Osaka Metropolitan Area? Sustainability 2021, 13, 13413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 77 Bank, Ltd. List of USD/JPY Exchange Rates (Intermediate). 2019. Available online: https://www.77bank.co.jp/kawase/usd2019.html (accessed on 6 November 2023). (In Japanese).

- Japanese Law Translation. Act on Land and Building Leases. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/ja/laws/view/3787 (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Hirayama, Y. Housing, Family, and Life-Course in Post-Growth Japan. Jpn. Archit. Rev. 2021, 4, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, Y. The Role of Home Ownership in Japan’s Aged Society. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2010, 25, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, Y. Housing Pathway Divergence in Japan’s Insecure Economy. Hous. Stud. 2010, 25, 777–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Tax Administration Agency. Statistical Survey of Actual Status for Salary in the Private Sector. Available online: https://www.nta.go.jp/publication/statistics/kokuzeicho/minkan/gaiyou/2021.htm (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Brumann, C. Outside the Glass Case: The Social Life of Urban Heritage in Kyoto. Am. Ethnol. 2009, 36, 276–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoto City Height Control Districts. Available online: https://www.city.kyoto.lg.jp/tokei/page/0000023106.html (accessed on 12 September 2023). (In Japanese).

- de la Calle-Vaquero, M.; García-hernández, M.; de Miguel, S.M. Urban Planning Regulations for Tourism in the Context of Overtourism. Applications in Historic Centres. Sustainability 2021, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, G.; Celata, F. Challenges and Effects of Short-Term Rentals Regulation: A Counterfactual Assessment of European Cities. Ann. Tour Res. 2023, 101, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoto City Projects That Utilize Accommodation Tax Revenues in 2023 in Kyoto City. Available online: https://www.city.kyoto.lg.jp/gyozai/cmsfiles/contents/0000275/275019/R05syukuhakuzei.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2023). (In Japanese).

- Nepal, R.; Nepal, S.K. Managing Overtourism through Economic Taxation: Policy Lessons from Five Countries. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 23, 1094–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| B | SE | t | VIF | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical center of Kyoto City | Houses for sale | (Content) | 3,358,036.60 | 3,072,848.00 | 1.09 | 0.28 | |

| SA | −30,551.73 | 112,231.60 | −0.27 | 1.04 | 0.79 | ||

| Hotel | 2,013,957.40 | 795,062.30 | 2.53 | 1.04 | 0.01 * | ||

| Houses for rent | (Content) | −1099.08 | 1037.52 | −1.06 | 0.29 | ||

| SA | −32.03 | 37.89 | −0.85 | 1.04 | 0.40 | ||

| Hotel | 479.15 | 268.45 | 1.78 | 1.04 | 0.08 | ||

| Outside center of Kyoto City | Houses for sale | (Content) | 3,611,673.70 | 896,414.40 | 4.03 | <0.01 ** | |

| SA | 90,074.05 | 51,850.86 | 1.74 | 1.51 | 0.08 | ||

| Hotel | −618,761.40 | 630,803.70 | −0.98 | 1.51 | 0.33 | ||

| Houses for rent | (Content) | −2040.82 | 341.31 | −5.98 | <0.01 ** | ||

| SA | 39.62 | 19.74 | 2.01 | 1.51 | 0.05 * | ||

| Hotel | 254.39 | 240.18 | 1.06 | 1.51 | 0.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoshida, M.; Kato, H. Housing Affordability Risk and Tourism Gentrification in Kyoto City. Sustainability 2024, 16, 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010309

Yoshida M, Kato H. Housing Affordability Risk and Tourism Gentrification in Kyoto City. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010309

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoshida, Mikio, and Haruka Kato. 2024. "Housing Affordability Risk and Tourism Gentrification in Kyoto City" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010309

APA StyleYoshida, M., & Kato, H. (2024). Housing Affordability Risk and Tourism Gentrification in Kyoto City. Sustainability, 16(1), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010309