Abstract

A circular economy is defined as a socially responsible, policy-driven model of business or enterprise operations that contributes to more sustainable society for both current and future generations. Although the implementation of circularity principles in the economy is a long process, the impact it creates on sustainability is long-term, and its benefits will be felt by all future generations. Therefore, the development of circularity in the European Union’s economy must progress, and more and more organizations should implement it as a good practice. The object of the article is the cooperation of civil sector outsourced services and the country’s military forces in the field of reverse logistics. Using a qualitative research methodology, the article demonstrates the potential for the country’s military forces to support the European Union’s circular economy initiative in the context of sustainability. This includes reducing the consumption of natural resources by increasing the value of the closed-loop supply chain and keeping products suitable for consumption as long as possible. Considering the fact that there is limited information dissemination within the military sector, this research presents one of the few opportunities to examine the integration of civilian and military sector efforts for sustainable development from a practical and scientific perspective. The conducted research demonstrates that the closed-loop supply chain and the military’s reverse logistics processes take place but are not fully integrated into one whole. They lack a unified whole directed towards a common goal when reverse logistics activities are correlated to closed-loop supply chain and national circular economy goals, as well as ensuring sustainability. Outsourced services are available and used in the military, in many cases even for reverse logistics activities (repair, storage, transportation, modernization, etc.). This research made it possible to prepare a conceptual model for the organization of the military’s reverse logistics using outsourced services, thereby ensuring the creation of a sustainable supply chain.

1. Introduction

According to Alcoforado [1], at the 2015 consumption rate, the demand for natural resources exceeded 41% of the Earth’s unused capacity. If this demand continues to increase at this rate, then by 2030, when the population is expected to reach 10 billion people, double the amount of natural resources will be needed to satisfy it.

In its 2015 annual report, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs highlighted that by 2030, global demand for land, food, and critical natural resources is projected to double compared to 2010 due to population growth [2].

Unfortunately, the developing global economy contributes to the destruction of the planet’s resources to a large extent. The majority of enterprises still operate on the basis of a linear take-make-dispose economic model, in which they transform the received raw material into a finished product and sell it on the market to the end consumer. In turn, the consumer throws away the product (consumed in full or in part). In this way, the manufactured product reaches the end of its life cycle [3]. With this linear approach, enterprises not only are not concerned about what happens to the product when it is thrown after its end-of-life use but also are not concerned about the resources used to produce the product.

Therefore, it is not surprising that more and more attention is paid to those looking for better resource and process efficiency in various production areas and at different stages of consumption and those using the principles of circular economy. The principles of the circular economy encourage reducing or eliminating waste and pollution, maximizing the efficiency of product and material use and promoting the natural regeneration of systems [4]. The circular economy is widely recognized for stimulating economic growth; creating new business and job opportunities; saving material costs; reducing prices; improving the security of supply; and, at the same time, reducing the impact on the environment [5]. Esposito et al. [6] assert that reverse logistics poses a significant challenge within the circular economy’s framework. They emphasize the challenge of collecting consumer waste to reclaim its value and transform materials into reusable resources. Such a circular model of reverse logistics allows not only the protection of the environment and the saving of raw materials but also the achievement of maximum financial results.

When the links between the circular economy and reverse logistics were analyzed, it was observed that researchers had paid little attention to the military reverse logistics system and its activities, operating in closed-loop supply chains and supporting the objectives of the circular economy. The absence of such analyses and the statements of researchers such as Strauka [7] and Larsen [8] encourage a closer examination of the processes of the circular economy, its principles, and the implementation of reverse logistics activities in the country’s military forces. It is worth noting that the functioning of the reverse logistics system of the country’s military forces and the use of outsourced services of the civilian sector have not been extensively studied so far. Therefore, if civilian outsourced services were used, would a reverse logistics system work better in a country’s military forces?

The object of the article is cooperation of civil sector outsourced services and the country’s military forces in the field of reverse logistics.

The aim of the article is to prepare a conceptual model of the reverse logistics system of the military forces using outsourced services.

Methods used: analysis of scientific literature, legal acts regulating the implementation of the circular economy in the country, and the regulation of reverse logistics in the country’s military forces. To clarify the collected information and prepare conclusions, an in-depth interview was conducted with logistics and procurement specialists of the country’s military forces.

The article consists of an introduction, three body parts, and conclusions. Section 2 analyzes the scientific literature, presenting the concepts of circular economy, closed-loop supply chain, reverse logistics, outsourced services, and various other aspects. Section 3 reveals the peculiarities of the empirical data collection and analysis process. Section 4 presents the results of the research, based on which the conceptual model is formulated. Finally, the article ends with a subsection of discussions and conclusions.

2. Review of Literature Sources

The European Commission presented a new European growth strategy based on the European Green Deal and the concept of competitive sustainability in its Annual Strategy in 2020. The European Union sets an ambitious goal for itself: to transition to a fully circular economy by 2050.

The circular economy offers ways and solutions to achieve a sustainable lifestyle and an environment-friendly economy. Since 2015, the European Commission has been developing an action plan for implementing the circular economy, which includes legal acts and industrial policy elements. Governments at all levels, enterprises, innovators, investors, and consumers play an important role and contribute to implementing the circular economy process and objectives [9].

The new circular economy action plan published by the European Commission in March 2020 aims to create a cleaner and more competitive Europe. It includes initiatives covering the entire life cycle of products, such as product design, promotion of circular economy processes, and promotion of sustainable consumption. It ensures that resources in the EU economy are used for as long as possible [10].

To ensure the sustainability of the European Union’s economy and turn climate and environmental problems into economic opportunities, enterprises are encouraged to switch to a clean circular economy. This cycle aims to preserve the value of raw materials, materials, and products as long as possible and reduce the amount of waste generated as much as possible. Enterprises are encouraged to pursue sustainable development by extending value through improved or new business models and services.

The circular economy is a social, environmental, and economic paradigm that aims to prevent resource loss and search for ways to preserve and restore the environment, using ecological, innovative solutions and products that can be reintroduced into biological and technical cycles/processes [11]. The circular economy interpretations proposed by various scholars are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of the circular economy.

The circular economy changes the traditional one-way linear economic model of “take–produce–throw” into a feedback circular economy mode of “raw material–product–waste–renewable raw material”, which complies with the concept of sustainable development and uses resources and protects the environment more efficiently to obtain the maximum economic and social benefits with minimal resource and environmental costs. According to Strauka [7], the circular economy includes five main areas: (1) make (product design and production processes), (2) use, (3) reuse, (4) remake using secondary raw materials, and (5) recycle.

According to Jiang and Zhou [15], the circular economy is essentially an ecological economy that requires human economic activity according to the principle of 3R (reduce, reuse, and recycle).

The circular economy pursues multifaceted goals: it encourages protecting the environment, saving materials, creating additional jobs, and saving money for producers and consumers. In his conclusions, McKinsey [16] states that the circular economy reduces enterprises’ dependence on limited natural resources and helps enterprises create greater value. As for the benefits of enterprises following the principles of the circular economy, Lopes de Sousa Jabbour [17] states that the most important benefits for enterprises are (1) reduction of raw material waste by reducing the use of energy and materials in production, which helps enterprises reduce waste and carbon emissions and reduce costs related to energy, waste management, and emission control, and (2) increase competitive advantage through process innovation.

The advantages provided by the circular economy are analyzed by various scientists; however, in practice, various challenges of the development and implementation of the circular economy are encountered. According to Strauka [7], the main challenges faced by enterprises in implementing circular economy goals are the lack of knowledge, competence, and resources; the confusing and unstable market demand; and complicated cooperation between different participants.

The circular economy integrates sustainability and business development, making it attractive to enterprises. According to Ritzén and Sandström [18], such integration is critical for many enterprises due to the ongoing consumption of resources beyond global capacity and the resulting negative environmental impact. However, the circular economy is rarely implemented in practice, and, if implemented at all, often is only done so fragmentarily. This is probably because transitioning from a traditional linear model to a circular economy model requires radical changes, time, and effort [18].

From a logistic point of view, the circular economy can be seen as the integrated direct and reverse management of the movement of products or materials in the supply chain [19]. Therefore, enterprises that have decided to apply/or are applying circular economy principles in their operating models must also apply these principles when adapting their supply chains [20].

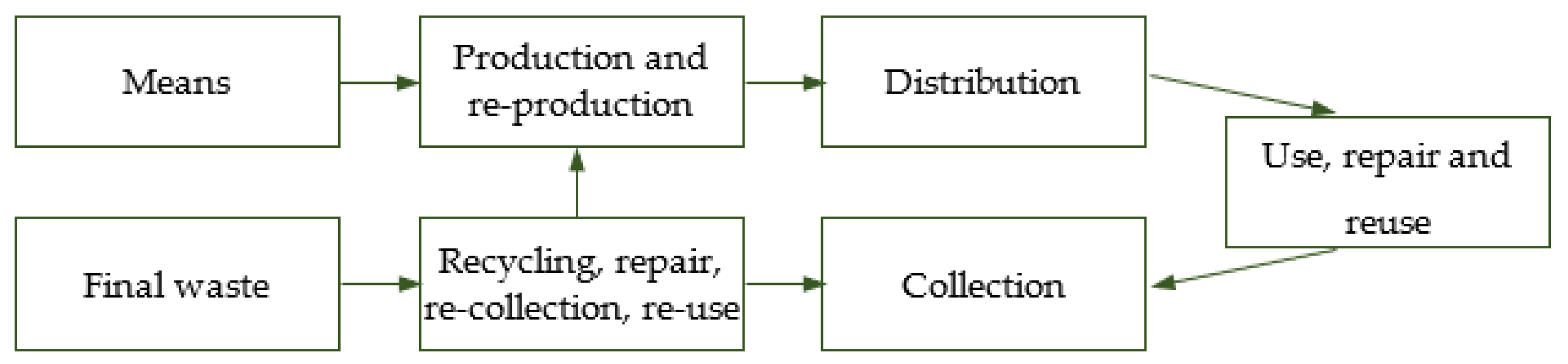

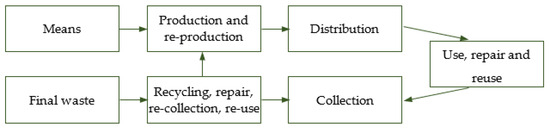

Considering the closed loop of the circular economy model, the same principle must be applied to supply chains—supply chains must also become closed. The supply chain model presented (see Figure 1) shows that in a circular economy, products and materials used in the supply chain that would be considered waste in the direct chain are taken back into the chain for new processes and reused.

Figure 1.

The supply chain of the circular economy [21].

Thus, closed-loop supply chains can be considered economically and ecologically sustainable. The purpose of such chains is to close the resources in the ring of the supply chain to achieve the highest level of material efficiency, creating added value in the supply chain [22].

According to Defee et al. [23], a closed-loop supply chain consists of five main processes: product acquisition, reverse logistics, inspection and disposition, reconditioning, and distribution and sales.

Generally, the most successful enterprises using closed-loop supply chains are those that closely coordinate them (closed-loop supply chains) with direct supply chains, creating a closed-loop system [24].

When the lack of raw materials began to appear in the global economy and environmental requirements appeared in legal acts, enterprises were forced to respond by adapting their supply chain systems and processes. The circular economy emphasizes the maximum circulation of end-of-life products and encourages the reuse or recycling of products. As part of this aspiration, reverse logistics has become a key component of the circular economy [25].

Esposito et al. [6] believe that one of the most difficult parts of the circular economy is reverse logistics. Therefore, to understand how important reverse logistics is for the circular economy (and at the same time for the reverse supply chain), it is necessary to clearly understand how reverse logistics is defined, what activities are assigned to it, and what goals and processes of reverse logistics are related to the circular economy.

In scientific articles, reverse logistics is defined in various ways:

- It is the process of moving the product back through the supply chain, during which it aims to serve the emerging number of materials in order to ensure the return of materials or products (return), condition determination (inspect), and recall [26].

- It is defined as the process of planning, implementation, and performance control aimed at cost-effectively managing the flow of raw materials, in-process inventories, finished goods, and related information as assets move from the point of consumption to the point of origin for value recovery or to the appropriate asset disposal/destruction [27].

- In the circular economy context, reverse logistics refers to activities and management that consider product returns; end-of-life processing of products; and recovery operations such as repair, refurbishing, reuse, and recycling [25].

We see that the definitions of reverse logistics focus on managing information and activities related to materials or products moving backwards from the consumer to the producer to maintain or recover the product’s value. Thus, reverse logistics contributes to the objectives of the circular economy: reducing the need for primary materials and protecting the environment and land resources.

When analyzing the activities undertaken in the context of reverse logistics and closed-loop supply chain, activities mentioned by various authors can be observed, which are also attributed to closed-loop supply chain and separate reverse logistics. Bernon et al. [25] distinguish the following activities when defining reverse logistics: the management action of logistics functions, reuse and recovery actions, distribution, recapturing values, and reverse flow or return, where the return can be when products are canceled, returned due to repair or renewal, and due to excess products. In turn, Fleischmann et al. [28] distinguished reverse logistics activities aimed at extracting value from returned products—these are collection, inspection and separation, reprocessing and disposal, and redistribution.

There is no unified, agreed-upon list of reverse logistics activities—activities can be broken down and supplemented by other processes that contribute to the goals of reverse logistics. The reverse supply chain and reverse logistics activities mentioned in Table 2 show the complexity and interdependence of these processes.

Table 2.

Reverse logistics and closed loop supply chain include activities.

The assessment of closed-loop supply chain and reverse logistics activities discussed in the scientific literature allows us to state that the activities are intertwined, and there is no clear separation of which activities should be treated only as closed-loop supply chain activities and which are classified only as reverse logistics activities. It is, therefore, not surprising that some authors, such as Govindan and Bouzono [30], use the concepts of closed-loop supply chain and reverse logistics interchangeably. This is also because some activities may be performed at different points/stages of the closed-loop supply chain, and some activities may be performed multiple times at different points in the closed-loop supply chain and at different times, with different purposes (e.g., transportation/checking/sorting).

For the further implementation of this research, we use the activities of reverse logistics defined by Fleichmann et al. [28], supplementing them with several activities mentioned in the definitions of the scientific literature of reverse logistics and the analysis of the activities.

We consider that reverse logistics activities are the following: collection of products/materials at the final point of consumption (this issue is widely analyzed by Goltsos et al. [31] and Defee et al. [23]), inspection of selected products/materials (this issue was extensively studied by Defee et al. [23]), separation of inspected products/materials, reprocessing of suitable materials/products (this issue was extensively studied by Defee et al. [23]), and redistribution and disposal (this issue was extensively studied by Defee et al. [23]). For the synchronization of all reverse activities and information management, combining it into the management action of logistics functions is an essential part of reverse logistics activities.

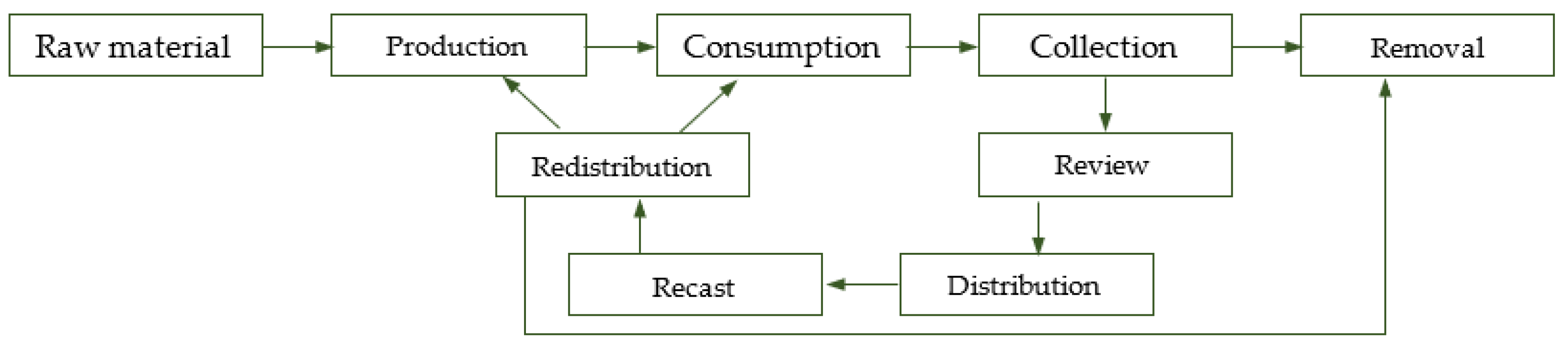

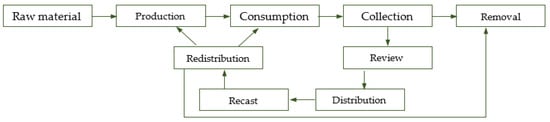

To ensure the implementation of circular economy principles in a closed-loop supply chain, a theoretical model of reverse logistics operations can be created by performing selected basic functions of reverse logistics (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Reverse logistics activity model in a closed loop supply chain (source: [1] adapted by the authors).

It is important to note that throughout the process, both the enterprise’s management and employees must have a good understanding of the actions and goals of each process. Bowersox et al. [31] state that long-term business profitability should increase with proper management of reverse logistics activities.

Therefore, when planning and executing these activities, the management of reverse logistics activities must be organized, involving all personnel and departments participating in the reverse logistics system, using practical management of activities, cooperating with other departments, and ensuring effective control of all these activities.

Reverse logistics is becoming a more widely used practice to close the loop and become part of a closed-loop (annular) supply chain. According to Govindan and Bouzon [30], as in many fields, in reverse logistics many factors influence the successful implementation of reverse logistics. Some factors can determine/accelerate the implementation of reverse logistics, while others, on the contrary, can slow it down. The factors proposed by Govindan and Bouzon [30] form a success circle for successful reverse logistics implementation, where each factor influences the next factor: economic benefits and financial status, legal framework or legislation, corporate social responsibility, and leadership and management.

In turn, Huscroft [32], in his circular supply chain implementation dissertation, distinguishes three areas where logistics specialists face challenges in implementing reverse logistics: communication challenges, information challenges, and challenges of reverse logistics.

Although many enterprises still tend to focus on building their own internal circular supply chain reverse logistics capabilities and organizations to ensure their core operations, inventory management, sales, or pricing, outsourcing solutions can offer enterprise performance monitoring, asset disposition, accounting capabilities, and services that better unlock the value of reverse logistics. Blackburn et al. [33] note that outsourced services in reverse logistics can be used to ensure the collection of tools, transportation of returned products, storage, destruction of unnecessary waste, and sorting or the entire management of waste management.

The reverse supply chain is usually not a core business of an enterprise; therefore, outsourcing this activity to a third-party outsourcing logistics (3PL) provider could be one of the most important solutions [34]. Similar opinions are also found by Efendigil et al. [35], who argue that a 3PL enterprise in a closed-loop supply chain could effectively ensure sustainability, as effective reverse logistics services enable businesses to increase profits, differentiate their services from competitors, attract new customers, and raise the enterprise’s status in the global supply chain network.

According to Sivanesan et al. [36], 3PL enterprises faced with managing returned products began to offer value-added services for reverse logistics by providing repair, remanufacturing, repacking, or relabeling services. Some 3PL enterprises tend to specialize in certain types of activities rather than trying to offer all possible service alternatives. Rushton et al. [37] prepared a summary of 3PL activities: warehousing and related services, stockpiling and accounting, and transporting.

Logozar [38] extends Rushton et al.’s [37] outsourcing activities to more closely reflect the needs of reverse logistics: collection and sorting of used products; consolidation and packaging of collected used products; inspection; information management [36]; and return of goods and their repair services [36].

Enterprises planning to use outsourced services must discuss in advance all possible operational barriers, processes, responsibilities, information exchange, and control mechanisms so that mutual activities are successful and long-term [39].

According to Green et al. [40], 3PL outsourcing logistics providers can help enterprises achieve their goals by providing the following benefits: (1) cost reduction through more efficient operations; (2) control of seasonal products (outsourced services at peak times); (3) reduced storage costs due to outsourced storage services, less downtime of warehouses during off-peak hours, there being no need to insure stored products; (4) improved customer service due to more timely and frequent deliveries and reverse logistics; (5) access to global markets through distribution networks and customer service; (6) better utilization of assets, as capital is no longer tied up in unnecessary storage costs or inventories; (7) savings are achieved because 3PL providers use shipment consolidation (consolidation of shipments, economies of scale); (8) reduced need for employees; (9) the ability to focus on the main activities of the enterprise; (10) eliminating the need for infrastructure; (11) decrease in the need for resources, especially transport capacity/transport maintenance and its maintenance and insurance; (12) risk sharing; (13) better cash flow; (14) inventory costs are reduced; (15) access to resources that are not available in the enterprise or organization; (16) use of the best information technologies for information tracking and exchange.

When using outsourced services, enterprises accept and receive the benefits provided and assume the risks of these services. Logistics functions provided by outsourced services directly impact the movement of raw materials or products in the supply chain and influence the structures and functions of the organization, which, in turn, can affect the entire business of the organization, causing its success or failure.

Summarizing the analysis of scientific literature, we can claim that the goals of the circular economy—to keep products and materials in the supply chain as long as possible, thereby increasing the value of the supply chain—can only be achieved in properly planned closed-loop supply chains in which reverse logistics activities play a significant role. The reverse logistics system and its processes must be arranged so that the symbiosis of reverse logistics activities brings maximum benefits to the supply chain and minimizes material waste. However, even efforts to manage reverse logistics processes with the help of information systems are constantly exposed to various risks, the management of which requires preparation at the initial stage of closed-loop supply chain planning.

Properly selected enterprises providing outsourced services outsourcing enterprise are of great importance in increasing the value of the supply chain. Procurement organizations, in order to achieve higher economic results or enterprise efficiency, must assess not only the planned fees, but also the risks that come with the service received, plan action plans, and risk mitigation measures.

In addition, the analysis of the latest sources [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] also showed that the greatest attention is paid to the circular economy and civilian logistics, as well as aspects of reverse logistics in it, while such a significant aspect as the interaction of circular and reverse logistics in the military sector is almost not examined. Therefore, this gap allows us to assume and inspire further discussion at the level of scientific research.

3. Research Methods and Methodology

The analysis of the scientific literature explored the challenges and objectives of the circular economy, which moves to a closed-loop supply chain. The analysis of closed-loop supply chain activities allowed us to identify the main activities where reverse logistics plays a key role. The analyzed and defined list of reverse logistics activities and challenges in reverse logistics will allow a closer look at the existing and possible processes and their activities of the reverse logistics system of the country’s military forces. Analysis of outsourced services has shown that using these services is a suitable means for enterprises to focus on their core activities, giving up and transferring part of the logistics functions to 3PL enterprises.

A qualitative research strategy was chosen for this study. Qualitative research allows us to not only examine the reverse logistics system in the country’s military forces but also to delve deeper into how the activities of that system are performed; what challenges arise in performing one or other reverse logistics activities; and to analyze the assessments, insights, and suggestions provided by specialists performing reverse logistics. For the analysis of the responsibilities and system of reverse logistics, an analysis of the available documents was undertaken using the document content analysis, which allows reliable conclusions to be drawn after an objective and systematic analysis of the features of the text. An in-depth interview was applied to expert interviews remotely to assess the reverse logistics system and its processes and learn how outsourced services support those processes. The information synthesis was used to complete the study and prepare a model of reverse logistics in the country’s military forces, which was approved by experts in logistics and procurement of the military forces.

The main laws of the European Union and the country, normative documents, and orders regulating the reverse logistics of the military forces were selected for document analysis to determine the regulation of implementing circular economy principles. The original documents were selected for analysis after identifying certain keywords and themes. We were looking for what is related to logistics activities, logistics activity processes, circular economy, reverse logistics, and outsourced services. The received documents were analyzed, and links to them were accessed, thereby maximally covering all linked documents and subsequent documents coming from them. The analyzed literature and documentation made it possible to prepare a questionnaire for an individual interview. The questions of the individual research questionnaire are divided into several problematic/interesting areas that are examined, and questions are prepared for these areas.

In the next step of the research, an in-depth interview was conducted to clarify the correctness of the results obtained in the first step. The research participants were selected purposefully after assessing the personal experiences and characteristics of potential research participants, which is likely to allow more accurate and detailed answers to the research questions. To obtain the most objective results of the individual interview research, interviews were planned with up to 12 logistics and/or procurement specialists. The exact number of research participants was planned to be decided using the “snowball” sampling by interviewing each research participant. It was determined that for the in-depth interview on this topic, senior military officers/civilians, and civil servant specialists who have served in the field of logistics for at least 15 years would be interviewed. Ideally, the research participants should have held various levels of management positions in the field of logistics/procurement. The assessment found that, currently, up to 48 senior officers and civilian specialists are serving in the country’s military forces in the field of logistics. Therefore, 15 invitations were sent voluntarily to participate in the study through individual interviews. However, only five invitees responded positively (by agreeing to participate in the research) to the invitation. In addition, such a small sample was influenced by the specifics of the topic and field and the data protection law. The change in the number of participants (from the planned 12 to 5 who agreed to participate in the study) did not affect the course of the study because after the fourth interview, it was noticed that the information of the specialists began to repeat itself, the opinions coincided, and the principle of information saturation was observed, i.e., new study participants did not provide any new information.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Principles of Organization of Reverse Logistics in the Country’s Military Forces

The aims, objectives, tasks, and principles of the development and implementation of the circular economy outlined in the legislation of the European Union and the country show that every economic entity participating in the circular economy process must have a developed and approved organizational system that supports the objectives of the circular economy and enables the organization to operate circularly.

To analyze the reverse logistics of the country’s military forces, as one of the main components of the circular economy, a search was made for laws accompanying the goals of the circular economy towards the responsibility of the institutions of the national defense system and involvement in the circularity of the country’s economy.

The National Security Framework Act [50] should be mentioned at this point, which states that “The state must ensure ecological security for the country’s population by guaranteeing sustainable economic development, contributing to the efforts of the international community to reduce global ecological threats, quickly responding to special ecological situations and eliminating and reducing their consequences” [50]. The same law states that “The state carries out the prevention of environmental pollution and other negative effects on the environment and human health, seeks to preserve the natural heritage values, landscape and biological diversity of the country, improves environmental quality monitoring, encourages the implementation of the best available production methods and the latest technologies with less negative impact on the environment in the farm, increasing not only the economic but also the ecological efficiency of enterprises, to conserve natural resources and reduce the negative impact on the environment” (National Security Framework Law, 1996). Although this may not be a direct task for the institutions that ensure the security of the State, based on the goals of the circular economy, here we clearly see the state’s commitment, through the prism of security, to conserve natural resources, increase the economic and ecological efficiency of enterprises, and reduce global ecological threats. All these are the goals of the circular economy, which are set in the legal acts and resolutions of the European Union, and which are planned to be implemented in the country using the action plan for the transition of Lithuania to the circular economy until 2035 (which is currently only a draft).

The analysis of the law on the organization of the national defense system and military service of the republic of the country in question (1998) found that the provisions of the National Security Framework Law regarding the conservation of natural resources, increasing the economic and ecological efficiency of enterprises or reducing global ecological threats have not been transferred. However, within the framework of this law, it is defined that the Minister of National Defense is responsible for the implementation of the defense policy, the performance of tasks and functions assigned to the national defense system, the development of the national defense system, and the effective use of the resources allocated to it, determining the resource policy and the procedure for their effective use and control [51]. These law provisions are general, without a specific link to the circular economy or reverse logistics. Still, the mentioned provisions of “resource policy”, “efficient use of resources”, and “order of efficient use and control” are also part of the circularity of the economy, where the aim is to use resources efficiently, create and manage efficient resource use processes, and ensure that these processes and activities are properly implemented.

To ensure the implementation of the responsibilities assigned to the Minister of National Defense regarding the policy of resources, the effective use of resources, and the effective use and control procedure, which would support the provisions of the National Security Framework Law regarding the conservation of natural resources, increasing the economic and ecological efficiency of enterprises, and reducing global ecological threats, the institutions of the national defense system (including the military forces) should be tasked (if this does not affect the state of combat readiness, reaction times, and performance of the tasks set by the army and its units and/or the armed forces as a whole) to follow the principles of circular economy and ensure the implementation of closed-loop supply chain activities in order to have defined and coordinated closed-loop supply chain processes (including reverse logistics processes and descriptions). To synchronize all the processes of the reverse logistics system and properly account for the resources traveling in the reverse logistics chain, it is necessary to have the necessary digital information systems; responsible institutions or persons appointed to ensure the operation of the processes of the reverse logistics system; and the preparation, refinement, co-adjustment, or coordination of logistic, legal acts, and the synchronization of actions between all interested and active participants in the process of this system.

Summarizing the tasks of the provisions approved in the documents governing the activities of the military forces, it can be concluded that all their activities cover the main activities of reverse logistics (collection of products, sorting, transportation, storage, inspection (dismantling, product testing, shredding), processing (repair, renewal, cleaning, re-picking), redistribution (re-marketing, re-selling, re-stocking), disposal (landfilling), and all this combined with logistics function management). However, it should also be noted here that there is a possible overlap/duplication of the functions performed in reverse logistics, where the functions to perform one activity are divided among several organizations, and sometimes the functions are duplicated.

Summarizing the analyzed main national defense and security legal acts, the national defense system and the operational provisions of the main logistics institutions and organizations of the army, we can see that the concept/term of reverse logistics of the military forces, which would support the development of the national circular economy, is not used. It can be stated that there is no unified concept of reverse logistics of the country’s military forces, which would give a general understanding of the importance, guidelines, and goals of reverse logistics in the context of the country’s circular economy. However, there are direct logistics activities (part of which are also part of reverse logistics) and individual reverse logistics activities coordinated through an established military chain of command and control. Unfortunately, the responsibilities established by the organizations of the country’s military forces to perform certain activities classified as reverse logistics or to support those activities are intertwined and possibly duplicates.

The activities classified as reverse logistics carried out by the structures of the military forces analyzed are not performed solely with internal military resources; part of the functions/activities are allowed to be purchased (outsourcing): repair of transport, weapons and equipment, storage, washing and disinfection of textiles, and the disposal of unnecessary and unsuitable assets. This shows that reverse logistics functions can be performed at least partially with the help of the civilian sector.

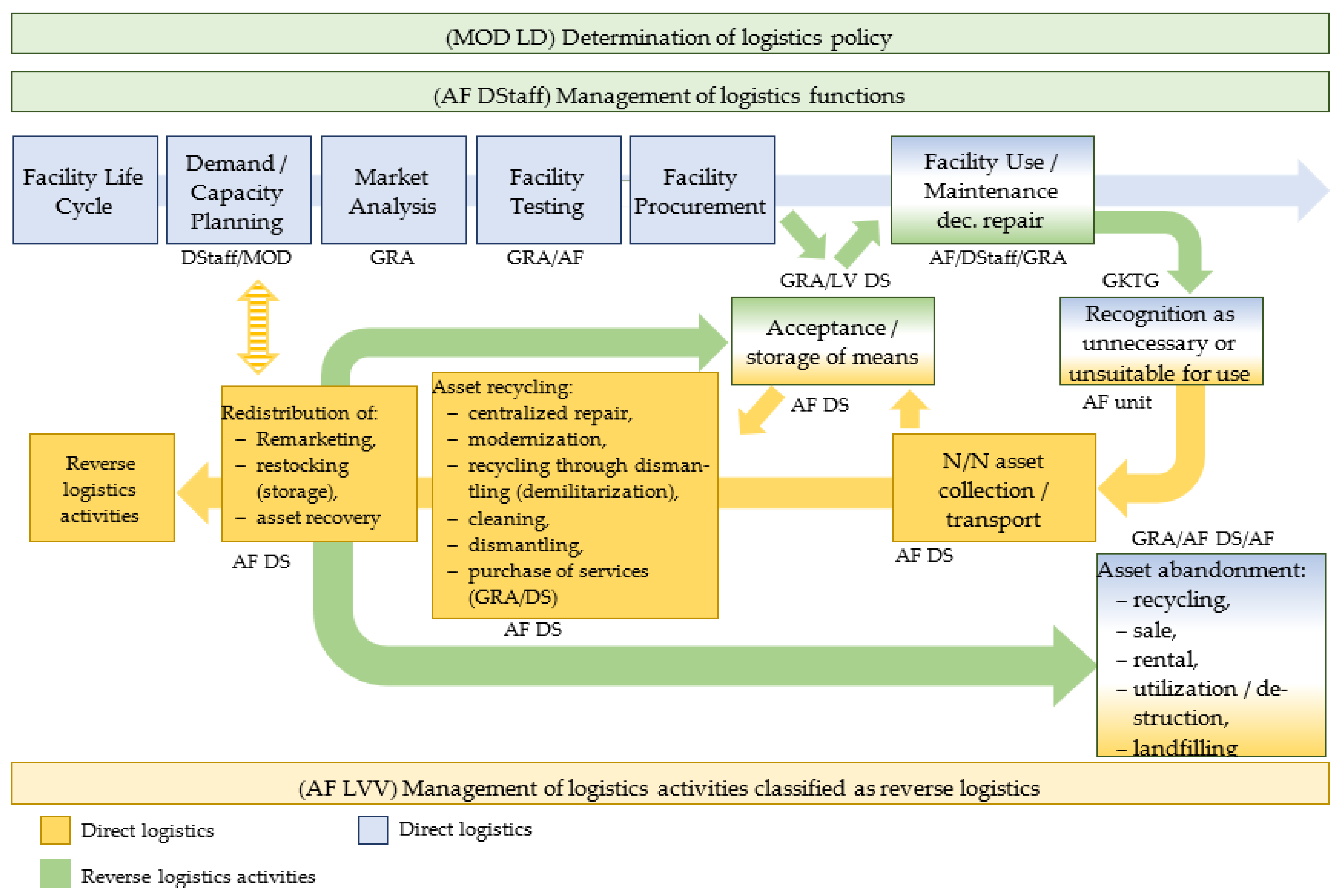

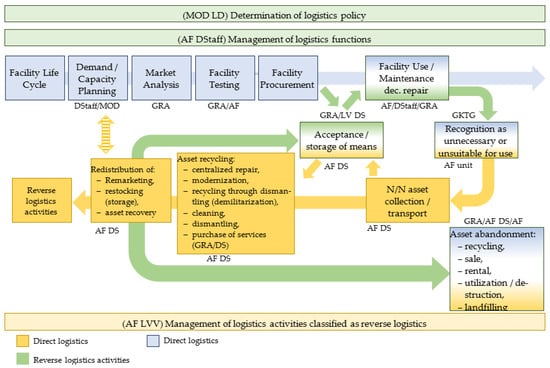

After analyzing the logistics responsibilities of the units of the country’s military forces and their supporting ministry-level structures, performing reverse logistics activities, we can draw up the current reverse logistics model of the military forces (see Figure 3). This model is part of the military’s closed-loop supply chain and supports the product life cycle stages.

Figure 3.

Scheme of logistics activities classified as reverse logistics of the country’s military forces in the closed-loop supply chain of the national defense system (source: compiled by author).

In today’s closed-loop supply chain, reverse logistics processes are closely linked to product life cycle processes. Activities throughout the chain revolve around several key processes: the capacity/requirement planning process/phase, the facility procurement process/phase, the facility usage/maintenance process/phase, and the facility write-off process/phase.

Summarizing the analysis of the organization of the reverse logistics system of the military forces and looking through the prism of the implementation of circular economy objectives, it can be seen that the orders/procedures of the Minister of National Defense and the institutions of the Ministry of National Defense authorized by the Minister of National Defense partially implement (partially ensure) the responsibility assigned to the Minister of National Defense in the Law on the Organization of the National Defense System and Military Service (1998) to implement resource policy for the efficient use of resources. It should be stated that the country’s current legal framework does not directly oblige the military to support/contribute to the development of the National Circular Economy. Although the Ministry of National Defense disposes of assets and uses them in such a way as to maximize the use of its resources (which corresponds to one of the objectives of the circular economy), their residual materials are included in the accounting and destroyed only when their further use is economically unprofitable. However, this is not enough to fully achieve the goals of the National Circular Economy (keeping products and materials in the supply chain as long as possible, increasing the value of the supply chain, reducing the need for primary materials, and conserving the environment and land resources). To operate efficiently in a closed-loop supply chain, not only the described processes are needed, but also clear responsibilities of all participants; a suitable information system; and, of course, a clear concept of a closed-loop supply chain based on circular economy principles with clear operating processes of the reverse logistics system.

4.2. Possibilities and Limitations of the Provision of Civilian Sector Outsourced Services in the Reverse Logistics of the Country’s Military Forces

Regarding the transfer of reverse logistics activities of the country’s military forces to the execution of outsourced services, it is important to mention that the structural entities participating in the implementation of reverse logistics activities have the options outlined in their regulations and existing procurement frameworks to do so.

The management of the Logistics Board, as the main coordinator of the execution of reverse logistics activities, has in its regulations the possibility of decentralized purchasing not only of goods but also of services and works. This allows for the management of the Logistics Board while ensuring the execution of reverse logistics activities, to purchase the necessary outsourced services of logistic functions—to carry out (outsourcing).

Analyzing the regulations of the Depot Service of the selected country’s army [52,53], we can see that the DS, with the help of its subordinate TVC, performs almost all activities classified as reverse logistics. The DS can carry out these activities using its own military capabilities or transfer these activities to civilian enterprises that perform outsourced logistics services (outsourcing)/3PL—in accordance with the provisions of the DS of the LM: DS of the LM conducts the procurement of goods, works, and services to ensure the proper and effective implementation of the tasks of the DS of the LM [54].

One of the main roles in the centralized procurement of outsourced services is performed through the Defense Resources Agency. The DRA organizes and coordinates the centralized procurement of goods, services, and works of the national security system, which is assigned to DRA competence.

The funding source is also important for the approval/implementation of the procurement of outsourced services. Given the fact that reverse logistics activities, through national legislation and European Union directives and resolutions, are related to the implementation of the circular economy goals of the European Union, there is an opportunity to apply for various EU funding programs and funding sources. The description of the procurement procedure provides that if the purchase of services and works is not financed from budget funds allocated to national defense, such services and such works can be procured.

It should be noted that there is an existing procurement description. However, although it defines the procedure for the organization, control, and supervision of procurements, it lacks the guidelines of the basic principles necessary for the successful execution of the purchased outsourced services contract, which would create prerequisites for procuring organizations to carry out more effective civil–military cooperation in the field of service procurement. The guiding principles of the main principles should include:

- Partnership and cooperation: The relationship of the outsourced services should be based on partnership and cooperation between the military and the outsourcing provider. Both parties must cooperate closely and share information, goals, and objectives to ensure smooth coordination and execution of reverse logistics activities. This principle emphasizes the need for open communication and trust between the military and the outsourcing provider.

- Visibility and transparency: Maintaining visibility and transparency throughout the reverse logistics process is essential. The military should have real-time access to relevant data, including the status of returned goods, repair progress, and inventory levels. This visibility enables informed decision making, improves responsiveness, and ensures outsourcing provider accountability.

- Standardization and compliance: Standardizing reverse logistics system processes is critical to maintaining consistency and efficiency. The military should establish clear guidelines, standard operating procedures, and quality control measures for the outsourcing provider to follow. Compliance with applicable regulations, such as environmental, security, and data protection standards, is also necessary to ensure legal and ethical practices.

- Performance evaluation and continuous improvement: Outsourcing reverse logistics activities should include regular performance measurement and evaluation. Key performance indicators should be established to measure the outsourcer’s performance, such as turnaround time, repair quality, and customer satisfaction. These metrics would allow the military to monitor progress, identify areas for improvement, and foster a culture of continuous improvement in reverse logistics operations on demand.

- Risk management and contingency planning: A reliable risk management system should be developed to address potential disruptions or challenges in reverse logistics system processes. The military and the outsourcing provider must work together to identify risks, develop contingency plans, and identify mitigation strategies. This principle ensures preparedness and resilience to unforeseen circumstances, minimizing any negative impact on reverse logistics operations.

- Cost optimization: Although cost optimization is important, it should not be the only focus when outsourcing reverse logistics activities. The military should consider the balance between cost savings and maintaining quality and efficiency. It is essential to estimate the total cost of outsourcing, including transportation, repair costs, and overhead costs in order to ensure the best value for money and meet operational requirements.

Following these principles, the country’s military forces could effectively outsource various reverse logistics activities, ensuring smooth return management, repair processes, and redeployment. These principles would facilitate cooperation, transparency, standardization, performance improvement, risk management, and cost optimization, which would increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the use of military logistics resources in the military reverse logistics system.

The analyzed situation of the organization in the provision of outsourced services in the civil sector allows us to get the impression that there are no clear obstacles as to why reverse logistics activities cannot be carried out with the help of outsourced services. On the contrary, military agencies performing core reverse logistics activities are empowered to purchase logistics services as needed to accomplish their missions. Ensuring reverse logistics activities through outsourced services/3PL enterprises does not limit the procurement order of the Ministry of National Defense, and some of such procurements are performed both centrally and decentralized.

Summarizing the analysis of the provision of outsourced services by the civilian sector in the reverse logistics of the country’s military forces, we can say that the purchase of outsourced services is possible, both according to the regulations approved by the entities participating in the reverse logistics system, and according to the existing procurement procedure. The successful execution of the acquired outsourcing contract would allow military personnel to focus on the essential logistics operations of the country’s military forces, saving costs and optimizing resources.

4.3. Reverse Logistics Situation Study

Individual interviews with logistics and procurement specialists not only made it possible to get a better picture of the country’s army’s current reverse logistics but also to understand the context of the current situation. Each research participant was asked questions according to a prepared semi-structured questionnaire, which allowed the interviewer to conduct the conversation more freely, clarify the questions, or ask questions out of order, depending on the course of the interview.

The research participants were asked 20 questions each, starting the interview with general questions, where the general questions gave an idea of the possible competence of the research participants in the field of interest.

Since the initial understanding of the research participants about reverse logistics, its concept, and the links between reverse logistics and the circular economy was limited at the initial stage, a short theoretical material was presented to all research participants a few days before the interview. This allowed the research participants and the researcher to talk more or less about the same things using the same concepts (circular economy, closed-loop supply chain, reverse logistics, reverse logistics activities) during the interviews.

All research participants supported the application of the principles of circularity in military logistics activities. There is no need for exceptions for military structures that ensure security—the principles of circularity must be applied, such as in other enterprises of the country or the European Union, because the army already carries out some activities in its activities; only they are not referred to as reverse logistics. However, the application of these principles in the army must not affect the level of combat readiness of the army, set response times, nor the execution of tasks, nor, most importantly, complicate and slow down the processes of military logistics.

According to research participants, a closed-loop supply chain exists in the country’s military, as does reverse logistics. All these processes and activities are mainly manifested in the field of logistics by fulfilling the requirements of the relevant legal acts. Envy was presented for the efficient use of assets when unnecessary material values are compulsorily included in the relevant lists from which any unit can look and “request” to be transferred to it for further use. Other processes are also carried out: recognition of assets as unnecessary and/or unsuitable (unusable), write-off, dismantling, and collection of residual materials or their transfer for utilization. The goals of all these activities are to make maximum use of the entire measurement resource, assess the possibility of secondary use, and dispose of it properly. Although these processes are not identified as reverse logistics activities in the military, they are all written out in write-off/transfer, maintenance, repair descriptions, and procedures.

The participants’ opinion regarding the execution of logistic activities classified as reverse logistics of the country’s army during a crisis/war turned out to be interesting. The “resurrection” of transport, weapons, and military equipment and the use of their components for maintaining the capabilities of the army is an important component. Therefore, during a crisis/war, logistics functions/activities directly supporting the maintenance of capabilities should be carried out. Still, the other part of reverse logistics activities, which is related to environmental friendliness, cost-effectiveness, and green logistics solutions, should be carried out minimally, or those requirements for the defense sector (including not only for the defense industry, but also for consumers of defense products) should be removed (stopped). This would allow operational logistics to operate without restrictions, quickly and efficiently, thus ensuring the support of the armed forces.

Logistics professionals mention the same few aspects in their answers about what they think should ensure the effective implementation of reverse logistics system processes in the military:

- Dissemination of clear guidelines from the top of the management (changes to legislation/concept/additions to procedures) for a common and unified understanding and goals of reverse logistics in the context of the national circular economy.

- Clear separation of functions in the closed-loop supply chain by directly performing reverse logistics activities and supporting reverse logistics activities.

- Management of activities through the created a clear management/execution chain/process with the help of trained and motivated personnel and adapted information technologies.

As for the clear responsibilities between the institutions/structures that carry out activities attributed to reverse logistics and those that support them—all interviewed specialists see the absence of a logistics management “pyramid”, duplication of functions, and lack of synchronization of actions. It was unanimously mentioned that one of the structures as the highest logistics organization helping to form the logistics policy should take a leading role in successfully organizing the reverse logistics system in the country’s military forces. Therefore, the review of the regulations and legal acts of the military units was repeatedly emphasized to clarify the processes of reverse logistics, where the Logistics Department would formulate the policy of logistics (including reverse logistics), the DStaff would set guidelines and tasks, and the military units would be the main executors.

All research participants were unanimous about the currently used electronic resource management information system. The system is needed; it is already proving itself (although it is still in its infancy and not all operational modules have been completed yet), and it already supports certain closed-loop supply chain and reverse logistics activities. eRVIS enables the military reverse logistics processes to operate faster and more efficiently and removes part of the workload from asset managers by providing the opportunity to track assets in a physical and financial sense and perform asset control in real time.

Also, one of the most interesting parts of interviewing military logistics and procurement specialists was their opinions on outsourcing for reverse logistics activities. In one way or another, it can be concluded that outsourcing frees up military logistics capacity, be it transportation, be it storage, or repair. One thing is clear—it “facilitates” military logistics and removes uncharacteristic functions from the military operational logistics. In times of crisis/war, the use of outsourced services would allow for a concentration on military logistical support; in times of peace, to focus on daily routine activities and preparation for the execution of direct tasks and crisis functions.

However, the use of outsourcing may be restricted, especially when it comes to military transport, weaponry, or other military equipment. This is related to the security accreditation of outsourced service enterprises—the ability to work with information that has some kind of secret label. Therefore, the procurement of Outsourced Services may be restricted regarding reverse logistics activities for material values of military purpose, civil–military (dual) purpose values, or simple civilian property.

The purchase of outsourced services also has other factors that influence their choice—this is also the lack of certain competence, the factor of time limits—when the services must be performed within a certain set deadline, and the available capabilities of the own army are not enough.

When choosing to switch to outsourced services, the potential risks associated with it must be assessed. As the main risk, all research participants mentioned the loss of asset control and asset visibility. To mitigate this risk, preparations must be made before choosing a suitable outsourced logistics service provider. For this, clear technical specifications must be prepared, requirements to ensure the visibility of assets in real-time using information technologies and a part (certain part) in implementing decisions related to the assets at the disposal of the military forces.

Summarizing the interviews of research participants, it can be claimed that logistics/procurement specialists of the country’s military forces see reverse logistics processes in the army. However, execution coordination requires a clearer division of responsibilities and a more active role of the accompanying institution. To achieve common goals in reverse logistics activities, the concept of circular economy/closed loop supply chain/reverse logistics in the military would help to solve some of the challenges, combining all activities into a single whole, thereby making a greater contribution of the military to the National Circular Economy. The transfer of reverse logistics activities to civilian outsourced services must be assessed through the logistics planning/operational logistics concept of defense plans, and potential risks and limitations must be assessed to maximally “free up” military logistics capabilities in peacetime.

4.4. Discussion

After analyzing the normative documents regulating the reverse logistics activities of the country’s military forces and conducting individual interviews with specialists in the field of military logistics and procurement, we can see that the reverse logistics system and its processes in the military are understood in a narrow sense, or that these terms are too new and too little discussed in the logistics community to lead deeper discussions about the impact of military reverse logistics on the closed-loop supply chain and what benefits it brings to the national circular economy.

However, the analyzed documents regulating logistics activities classified as reverse logistics and individual interviews did not show the inefficiencies of reverse logistics processes/activities carried out in the existing closed-loop supply chain. As mentioned, most of the logistics activities that belong to reverse logistics have been carried out for many years. Only integrating those activities for a common goal is still debatable, as are some possible overlapping or incompletely performed responsibilities.

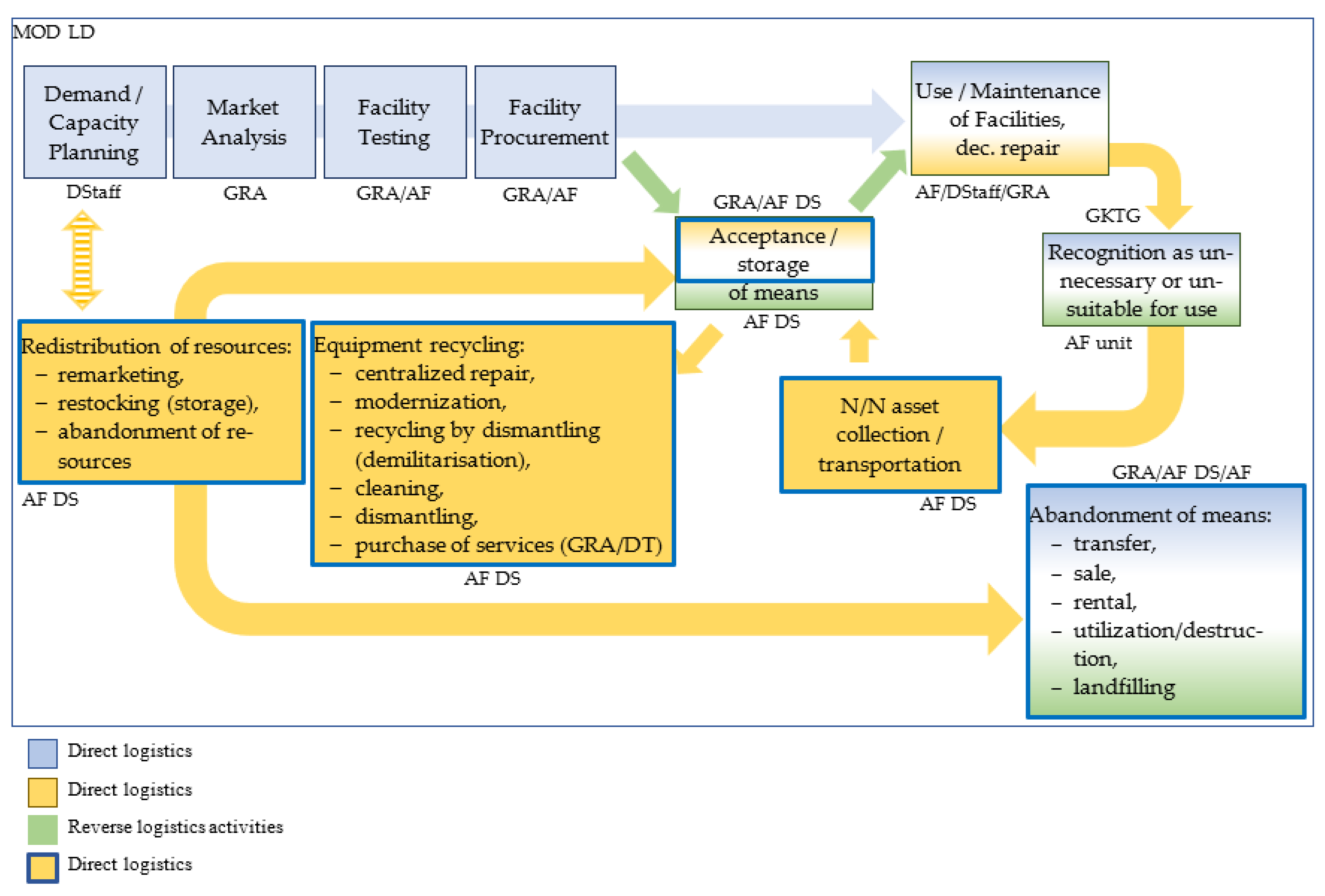

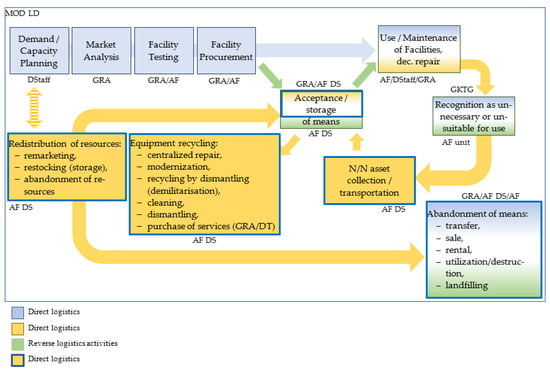

The proposed model of reverse logistics activities of the country’s military forces in the closed-loop supply chain of the NDS is quite identical to the one whose activities are carried out today (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Conceptual model of the reverse logistics system of the country’s military forces in the closed-loop supply chain of the national defense system (source: compiled by author).

The essential difference in this proposed scheme compared to the scheme of current activities is that reverse logistics in the country’s military forces is acknowledged. We can see that the reverse logistics activities were carried out according to the outlined procedures and descriptions. Still, those activities were associated either with the life cycle of the equipment or with environmental aspects. This model (Figure 4) combines all reverse logistics activities, initiates a new “project” called “Military Forces in the Context of the National Circular Economy” and “assigns” a force organization to lead this “project”.

The proposed model ensures a smoother connection between the reverse logistics system and the new equipment planning process, so that these processes are combined and understood as a single whole. The beginning of equipment planning is already associated with the circularity of the supply chain and the planned write-off/abandonment/repair/renewal/resale of equipment, etc.

Given that processing a returned product requires an average of 12 times more steps than managing direct logistics, the management of reverse logistics activities becomes even more important. Therefore, it would be quite logical to ensure the management of material assets moving backwards with an information accounting system, which would allow access to the necessary information as quickly as possible to be seen in various sections. The military’s electronic resource management system (eRVIS) should become (remain) this tool for the proposed reverse logistics activity model of the country’s military forces, but in terms of the requirements for the eRVIS system itself, the way in which it should support reverse logistics should be reviewed and supplemented if necessary.

The final difference of this proposed model compared to the current scheme of operations is that it is proposed to outsource reverse logistics activities (those that are possible due to security/where there are no restrictions to reduce the level of readiness of military units) to the execution of outsourced services (marked in blue defined squares in Figure 4). It is likely that in this way it would be possible to obtain wider and better warehousing services; to have more operative and flexible transportation, repair, disassembly, inspection, and logistic-consulting services; to abandon the functions uncharacteristic of military logistics in times of crisis/war (at the same time, also in times of peace); to have savings in logistics positions/personnel of the logistical orientation; and to be reassigned to positions not occupied by the military. The transfer of reverse logistics activities to outsourced service providers frees up/enables the redistribution of available military logistic equipment capacities and infrastructure storage capacities, and it reduces/eliminates infrastructure maintenance and maintenance costs. Therefore, the transition to outsourced services must be carefully planned and evaluated case by case.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the scientific literature made it possible to identify that to maintain the value of assets in the supply chain as long as possible; it is necessary to ensure the operation of a closed-loop supply chain, where reverse logistics activities have a significant influence. The literature analysis also showed that outsourcing reverse logistics activities is a suitable means of increasing the value of the closed-loop supply chain.

To ensure the longest possible maintenance of the value of assets available to the military in the NDS closed-loop supply chain, it is necessary to have a suitable model of the military reverse logistics system, which allows for defining the responsibilities of its participants and the possibility of sharing or transferring part of the responsibilities to outsourcing providers. Currently, the procedures and descriptions in the national defense system do not directly name or talk about NDS’s closed-loop supply chain and the military’s reverse logistics, though the activities attributed to reverse logistics are described in detail. Still, a connecting whole and a clear purpose for those activities are missing, linking them to the closed-loop supply chain and national circular economy goals. Responsibilities of participants in the closed-loop supply chain are defined, but, in places, may overlap. Outsourced services in the military are possible and partially used, ensuring reverse logistics activities (repair, storage, transportation, modernization, etc.).

The analysis of the current situation of the reverse logistics of the army and the interpretation of the interview data made it possible to create a conceptual model of the closed-loop supply chain, which allows us to re-evaluate and more clearly define the responsibilities of the participants in the reverse logistics system and to predict the necessary actions when transitioning to the execution of reverse logistics outsourced services.

It is likely that after these actions, the military reverse logistics system will be properly regulated as part of the country’s circular economy. Individual reverse logistics activities will have a common goal and place in the closed-loop supply chain. Using outsourced services to implement reverse logistics activities will enable the redistribution of freed military logistics resources to perform direct tasks, ensuring the logistical support of Lithuanian military units. Research area and sample limitation, data classification, etc., have become big challenges in conducting various types of research in military organizations. However, looking at future perspectives, the research could focus on SWOT, also on researching the good practices of other countries’ military organizations and drawing up common models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.V., S.I. and K.Č.; methodology, A.V.V. and S.I.; software, A.V.V. and K.Č.; validation, A.V.V., K.Č. and S.I.; formal analysis, A.V.V., K.Č. and S.I.; investigation, A.V.V. and S.I.; resources, A.V.V., K.Č. and S.I.; data curation, A.V.V. and S.I.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.V. and S.I.; writing—review and editing, A.V.V. and K.Č.; visualization, K.Č. and S.I.; supervision, A.V.V. and S.I.; project administration, A.V.V. and K.Č.; funding acquisition, K.Č. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request to the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alcoforado, F. The Circular Economy to Avoid Depletion of Natural Resources of Planet Earth. In Global Education Magazine; Education for Life: Nevada City, CA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://globaleducationmagazine.com/circular-economy-avoid-depletion-natural-resources-planet-earth/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. News; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/news/2015.html (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Ghisellini, P.; Ripa, M.; Ulgiati, S. Exploring environmental and economic costs and benefits of a circular economy approach to the construction and demolition sector. A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 618–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelis, R.; Howard, M.; Miemczyk, J. Supply Chain Management and the Circular Economy: Towards the Circular Supply Chain. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 29, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Tse, T.; Soufani, K. Reverse logistics for postal services within a circular economy. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 60, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauka, O.; Popova, B.; Jonaitis, T. Europos Žaliojo Kurso Galimybės Lietuvai: Perėjimas Žiedinės Ekonomikos Link Bei Stiprybių, Silpnybių, Galimybių Bei Grėsmių Apžvalga. Teminis Tyrimas Yra Parengtas Vyriausybės Kanceliarijos Įgyvendinamo Projekto „Atviros Vyriausybės Iniciatyvos“ Metu. 2020. Available online: https://data.kurklt.lt/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/perejimas-ziedines-ekonomikos-link-bei-stiprybiu-silpnybiu-galimybiu-bei-gresmiu-apzvalga-1.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Larsen, S.B.; Masi, D.; Feibert, D.C.; Jacobsen, P. How the reverse supply chain impacts the firm’s financial performance: A manufacturer’s perspective. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 284–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal (COM(2019) 640); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-con-tent/LT/TXT/?qid=1576150542719&uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document in 2022 Review of the Implementation of Environmental Provisions Country Report—Lithuania; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-09/Lithuania%20-%20EIR%20Country%20Report%202022%20%28LT%29.PDF (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Ormazabal, M.; Jaca, C.; Viles, E. Key elements in assessing circular economy implementation in small and medium-sized enterprises. BSE 2018, 27, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Nuur, C.; Feldmann, A.; Birkie, S.E. Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, F. Circular business models: Business approach as driver or obstructer of sustainability transitions? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 224, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhou, L.-J. Study on Green Supply Chain Management Based on Circular Economy. Phys. Procedia 2012, 25, 1682–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey Global Institute. Jobs Lost, Jobs Gained: Workforce Transitions in a Time of Automation; McKinsey & Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017; Available online: www.mckinsey.com/mg (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- de Sousa Jabbour, A.L. Going in circles: New business models for efficiency and value. J. Bus. Strategy 2019, 40, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzén, S.; Sandström, G.Ö. Barriers to the Circular Economy—Integration of Perspectives and Domains. Procedia CIRP 2017, 64, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beames, A.; Claassen, G.D.H.; Akkerman, R. Logistics in the Circular Economy: Challenges and Opportunities. In Strategic Decision Making for Sustainable Management of Industrial Networks; Greening of Industry Networks Studies; Rezaei, J., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Gold, S.; Bocken, N.M.P. A Review and Typology of Circular Economy Business Model Patterns. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 23, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.K.K.; Battaïa, O.; Cung, V.-D.; Dolgui, A. Collection-disassembly problem in reverse supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 183 Pt B, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide, V.D.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. OR FORUM—The Evolution of Closed-Loop Supply Chain Research. Oper. Res. 2009, 57, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defee, C.C.; Esper, T.; Mollenkopf, D. Leveraging closed-loop orientation and leadership for environmental sustainability. SCM 2009, 14, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide, V.D., Jr.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. The reverse supply chain. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 18, 25–26. Available online: https://hbr.org/2002/02/the-reverse-supply-chain (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Bernon, M.; Tjahjono, B.; Ripanti, E.F. Aligning Retail Reverse Logistics Practice with Circular Economy Values: An Exploratory Framework. PPC 2018, 29, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, D. Moving Ahead by Mastering the Reverse Supply Chain. In IndustryWeek; Penton: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.industryweek.com/leadership/companies-executives/article/21949246/moving-ahead-by-mastering-the-reverse-supply-chain (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Grant, D. Fundamentals of Logistics Management; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann, M. Quantitative Models for Reverse Logistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goltsos, T.E.; Ponte, B.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Naim, M.M.; Syntetos, A.A. The boomerang returns? Accounting for the impact of uncertainties on the dynamics of remanufacturing systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7361–7394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Bouzon, M. From a literature review to a multi-perspective framework for reverse logistics barriers and drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 318–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowersox, D.J.; Closs, D.J.; Cooper, M.B.; Bowersox, J.C. Supply Chain Logistics Management; Mc Graw Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Huscroft, J. The Reverse Logistics Process in the Supply Chain and Managing Its Implementation. Master’s Thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, 2010. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/b8c09b5bed58ffa42b1b7b254a6a21e0/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Blackburn, J.; Guide, D.; Souza, G.; Van Wassenhove, L. Reverse Supply Chains for Commercial Returns. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 46, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrato, M.A.; Ryan, S.M.; Gaytán, J. A Markov decision model to evaluate outsourcing in reverse logistics. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 45, 4289–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendigil, T.; Önüt, S.; Kongar, E. A holistic approach for selecting a third-party reverse logistics provider in the presence of vagueness. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2008, 54, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanesan, M.; Pugazhendhi, S.; Ganesh, K. Role of Third Party Logistics Providers in Reverse Logistics. Int. J. Syst. Syst. Eng. 2011, 1, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, A.; Walker, S. International Logistics and Supply Chain Outsourcing: From Local to Global, 1st ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Logožar, K. Outsourcing Reverse Logistics. In Zagreb International Review of Economics and Business; Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Zagreb: Zagreb, Croatia, 2008; Volume 11, pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bajec, P. Evolution of Traditional Outsourcing into Innovative Intelligent Outsourcing—Smartsourcing. Promet-Traf. Transp. 2009, 21, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, F.B.; Turner, W.; Roberts, S.; Nagendra, A.; Wininger, E. A Practitioners Perspective On The Role Of A Third-Party Logistics Provider. JBER 2008, 6, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martins, V.W.B.; Nunes, D.R.L.; Melo, A.C.S.; Brandão, R.; Braga Júnior, A.E.; Nagata, V.M.N. Analysis of the Activities That Make Up the Reverse Logistics Processes and Their Importance for the Future of Logistics Networks: An Exploratory Study Using the TOPSIS Technique. Logistics 2022, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omosa, G.B.; Numfor, S.A.; Kosacka-Olejnik, M. Modeling a Reverse Logistics Supply Chain for End-of-Life Vehicle Recycling Risk Management: A Fuzzy Risk Analysis Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, N.; Antunes, J.; Barreto, L. Impact of Management and Reverse Logistics on Recycling in a War Scenario. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabo, A.-A.A.; Hosseinian-Far, A. An Integrated Methodology for Enhancing Reverse Logistics Flows and Networks in Industry 5.0. Logistics 2023, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.; Zhao, X.; Wang, M. The Optimal Combination between Recycling Channel and Logistics Service Outsourcing in a Closed-Loop Supply Chain Considering Consumers’ Environmental Awareness. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.; Rosado, D.P.; Cohen, Y.; Pousa, C.; Cavalieri, A. Green Defense Industries in the European Union: The Case of the Battle Dress Uniform for Circular Economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wang, T.; Chan, P.W. Forward and reverse logistics for circular economy in construction: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 135981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janikowski, R. Transformation towards a circular economy in the Polish armed forces. Econ. Environ. 2020, 73, 9. Available online: https://ekonomiaisrodowisko.pl/journal/article/view/31 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Zhang, A.; Hartley, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Special issue Editorial: Logistics and supply chain management in an era of circular economy. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 166, 102911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietuvos Respublikos Nacionalinio Saugumo Pagrindų Įstatymas, 1996, Nr. VIII-49 [National Security Framework Act]. 1996. Available online: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.34169/asr (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Lietuvos Respublikos Krašto Apsaugos Sistemos Organizavimo Ir Karo Tarnybos Įstatymas. 1998, Nr. VIII-723 [Law on the Organization of the National Defense System and Military Service]. 1998. Available online: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalActEditions/lt/TAD/TAIS.56646 (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė. Dėl Lietuvos Respublikos Krašto Apsaugos Ministerijos Logistikos Departamento Nuostatų Ir Jo Skyrių Nuostatų Patvirtinimo; 2014 m. Spalio 31 d., Nr. V-1040; Depot Service of the Selected Country’s Army (Ministry of National Defense): Vilnius, Lithuania, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė. Dėl Logistikos Valdybos Depų Tarnybos Nuostatų Patvirtinimo; 2014 m. Rugsėjo 18 d., Nr. V-859; Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lietuvos Kariuomenės Depų Tarnybos Vado Įsakymas. Dėl Lietuvos Kariuomenės Deptų Tarnybos Turto Valdymo Centro Nuostatų Patvirtinimo; 2023 m. vasario 24 d., Nr. V-248; Lietuvos Kariuomenės Depų Tarnybos Vado Įsakymas: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).