Abstract

This research investigates the intersection of paramedicine and environmental sustainability (ES) by using mixed methods (surveys and policy analysis) to analyze organizational policy and professional beliefs. It advocates integrating ES into paramedic training and operations to reflect broader environmental values, and challenges, of a sector providing first response service delivery to climate-induced emergencies. Assessing paramedics’ willingness/interest in environmental education, timing (foundational or continuing professional development/CPD and organizational policy governing accreditation and practice in Australia and New Zealand (ANZ) found growing awareness of paramedics’ role in environmental stewardship. Disparity, however, exists between individual interest in ES training and its systemic exclusion in CPD policy and standards. The relevance of sociological thought, specifically Durkheimian theory, for construing ES interdependently, rather than individualistically (as predominated in the under-researched area) is advanced to promote ES reconceptualization, goal articulation and measurement. Results and practical recommendations are discussed amidst multidisciplinary literature to further emerging ES values exhibited in ANZ policy and paramedic beliefs. The article concludes systemic change is timely. Specifically, embedding ES into foundational and/or CPD training may leverage the professional interest found in the study and, importantly, ensure emergency practices promote the long-term environmental health prerequisite to supporting human health, congruent with the sector’s remit.

1. Introduction

This article investigates beliefs and formal policy guiding environmental sustainability (ES) in Australian and New Zealand (ANZ) paramedicine. A profession dedicated to service delivery during an era of heightened, globalized environmental degradation, the research analyzes surveys of paramedics and the national policy guiding ES education and practice. Paramedicine is an accredited profession requiring completion of accredited degrees, registration and compliance with national practice standards. Much, if not all, ES education/training falls under the remit of continuing professional development (CPD), rather than higher education curricula. As a quasi-privatized, self-governing sector, paramedicine creates training policies and sets goals that change or perpetuate ES knowledge and practice. Thus, it is imperative to identify beliefs underscoring ES practice.

Education, law, politics and governance are major social institutions affecting the social construction of knowledge [1]. Environmental values and environmental problem (EP) construction hinge on individual beliefs, formal and informal actions, institutional goals and best practices. Institutionalization of pro-environmental values is necessary for behavioral change that supports sustainable futures [2]. Unfortunately, environmental values are ideologically contested. On one hand, governments and international organizations promote global sustainability goals [3]. On the other hand, privatization leaves ES largely up to organizations and individuals. UN reports reveal unsustainable human goals and values continue trumping substantially addressing EP from land, air and water degradation. Subsequently, “the world is currently facing the largest extinction event since the dinosaurs disappeared. Habitat destruction, invasive species, overexploitation, illegal wildlife trade, pollution and climate change are propelling this crisis” [3] (p. 43). Increased global acidification and plastic pollution in oceans, greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, failed biodiversity funding and protection, unsustainable production and consumption, urban expansion, inadequate policy and intermittent and partial industry reporting/disclosing of ES practices escalate EP.

Although ANZ, the researched location, experienced a 19% increase in company-published ES reports between 2020 and 2021, there is a steady 30% reduction in global reporting of sustainable production and consumption [3]. Increased public procurement reporting coexists with decreased ES implementation. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, change “requires raising ambition, covering entire economies and moving towards climate-resilient development, while outlining a clear path to achieve net-zero emissions. Time is running out, and immediate measures are necessary to avoid catastrophic consequences and secure a sustainable future for generations to come” [3] (p. 38). Decentralized legal and governance systems, legislator re-election processes, interest groups, institutional biases and the policy-making cycle further deprioritize urgent pro-environmental action [4].

Sociologically, laws illustrate the politicalization of national values and power relationships inherent in their creation and enforcement. Environmental legislation disparately supports ES accountability and is costly and time-consuming, particularly where EP are deprioritized by policy-makers inclined towards growth and development ideology [4]. ANZ environmental laws are governed by justice systems modeled on British common law, causing problems similar to those experienced in America and Canada [4]. Stymied by an ‘adversarial’ approach to EP, legal pursuit requires following a rigid structure whereby laws, acts and regulations are administered by different branches, each requiring stringent qualifications to be met prior to proceeding [4] (p. 46). Hence, the relevance of policy—its existence and goals—as an alternative to law for improving ES is noteworthy, particularly in conjunction with education targeted towards ES goals and values. “The type of regulation developed for an EP and the interests that are benefited by the regulation are, to a large extent, determined by the ability of participants to exercise influence on the policy-making process” [4] (pp. 47–48).

According to the UN, “education today is in deep crisis” [3] (p. 52), with research finding quality, inclusive education inadequately prepares healthy future employees to tackle climate mitigation [5]. Understanding what ANZ paramedicine considers ‘important’ educative goals requires investigating education policy and beliefs driving paramedic workforce preparation. Paramedics frequently respond to climate change-induced disasters, such as fires, floods and heatwaves, and thus occupy a unique position of witnessing the human toll of climate change, whilst relying heavily on processes contributing significantly to environmental degradation [6,7]. Globally, the health sector accounts for 4.4% of the total carbon footprint, with developed nations, including Australia, America and the UK shouldering a larger (5–10%) burden [7]. The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) surpasses entire countries, such as Croatia, in carbon emissions, accentuating the urgency of sustainability measures [8]. Optimizing ES in the healthcare sector must surpass political reactivity to voter concerns, or lack thereof. ES aligns with the sector’s primary objective—enhancing human health—by improving quality-of-life and minimizing mortality rates; these goals must be accomplished without detracting from health by accelerating climate change.

Climate change gained academic salience among healthcare professionals in the past decade [7]. Attention must now shift towards operational priorities that mitigate global climate events. Paramedic organizations face unique challenges in adopting sustainability principles. Ambulance operation consumes sizable fossil fuel that exacerbates greenhouse gas emissions, paradoxically, while attending to climate change-induced natural disasters where paramedics treat more patients and experience longer ambulance idling times outside busy hospitals that fuel emergency equipment accounting for up to 65% of fuel consumed [8]. Energy-related innovations, such as solar panels for emergency equipment, face financial constraints with widespread adoption, yet remain a common target for ES initiatives as recycling medical materials from ambulance work is challenged by single-use necessities and space-restricted environments [8]. Measuring sustainability policy implementation in decentralized, quasi-autonomous workspaces of individual ambulances also relies on practitioner ‘buy-in’, underscoring the need for informed practice [8]. Similarly, calls to address climate change knowledge gaps in paramedic accreditation, such as undergraduate coursework, have encountered resistance from providers citing limited curriculum space [9]. Given nursing and other health sectors have substantial CPD training which, in the UK, is embedded in a ‘NetZero Plan’ [8], scope exists to enhance ES training so the paramedic sector may develop and implement suitable innovations. There is urgent need to enhance CPD curriculum and cultivate a professional culture aligned with sustainability measures [9,10] to better align the profession with international practice exhibited by UK counterparts [8].

The article next introduces the mixed-methods social research design adopted to document ANZ paramedics’ beliefs about ES education, as part of CPD and policy guiding the sector. Informed by sociological and political theory establishing individual values are systemically influenced by social institutions, results from a non-representative voluntary, unremunerated survey of 86 paramedics are juxtaposed alongside a bi-national policy analysis of ES in professional training policy. Findings commence filling research gaps noted in global ES education and paramedicine literature [11] and methodologically contribute to the dearth of policy analysis [12]. Broadly, the article establishes a precedent for future research to expand understanding “how and why certain policies come to be developed in particular contexts, by who, for whom, based on what assumptions and with what effect” [13] (p. 97) in ES education, CPD and ES goal achievement in ANZ paramedicine and beyond. Furthering knowledge about what socially predicates ES policy-making, specifically ES CPD in paramedicine, as part of the UN Sustainability Goal 4, promoting inclusive, quality lifelong learning opportunities [2], augments a global, multi-disciplinary literature predominated by psychological investigations of students [14,15,16,17]. Finally, by contributing a sociological analysis of professionals—employed paramedics—and the policy guiding their professional practice, we document individual willingness to undertake ES training, opportunities and policy gaps or alignment afforded for ES paramedicine policy goals and accountability measures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Methodology

Since the research design included collecting primary survey data from paramedics, human research ethics clearance (application #H21065) was obtained from Charles Sturt University’s Faculty of Health Sciences, in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council, in conjunction with the Australasian College of Paramedicine (ACP). The research design used mixed methods. Mixed methods minimize biases and limitations inherent to singularly using qualitative or quantitative methodologies [18]. Epistemological benefits, derived from using a mixed-method design, stem from blending positivist and interpretivist paradigms [19]. The two methods chosen, online surveys and policy analysis, are informed by sociological and political theory conceptualizing how and why change occurs.

2.2. Online Surveys

The survey analysis sought to answer five research questions (RQ), RQ1–RQ5:

- RQ1—Would most ANZ paramedics like to Learn about ES?

- RQ2—Would most ANZ paramedics Attend relevant, optional ES training?

- RQ3—Do ANZ paramedics believe ES should be taught in paramedic Training?

- RQ4—Do ANZ paramedics believe ES should be taught in Career development?

- RQ5—Do ANZ paramedics statistically differ by demographics RQ 1–4 for age, educational degree, ethnicity, gender, immigration status, location, or paramedicine employment duration?

Answer options used a 5 point Likert scale. The results obtained were analyzed using four dependent variables (Learn, Attend, Training, Career). Data were entered into SPSS, version 27, cleaned, cross-checked and nonparametric statistics run to describe the sample. This article reports significant results for correlations and chi square tests of difference in beliefs and intentions about ES teaching/learning by paramedics’ demographic factors (age, educational degree, ethnicity, gender, immigration status, location and paramedicine employment duration).

Initial survey questions were informed by an exhaustive review of ES literature and adapted for ANZ cultural suitability. Given the absence of ES survey research in paramedicine, all survey questions were submitted to the ACP Research Advisory Committee, which provided feedback to support instrument validity relevant to the research population. Reliability and validity [20] were enhanced by survey piloting, with feedback incorporated for distribution between the first round (September–November, 2021) and second round (September–November, 2023). The time gap allowed for avoiding sampling during heightened COVID pandemic lockdown and emergency response, whilst maximizing research participation opportunity for a heavily burdened research population.

The ACP managed recruitment and distribution of all online survey participation. A whole population sampling framework [21] was adopted, whereby accredited paramedics in every New Zealand and Australian state/territory were invited to participate. Survey access measures prevented duplicate completion by any individual. This yielded a total sample of n = 86. Although the non-probability sampling framework yields survey results neither representative nor generalizable to all ANZ paramedics, the methods employed are suitable for answering the research question as part of a mixed-methods analysis [22] providing exploratory data and maximizing research participation [23] from busy professionals for an under-researched topic affecting paramedic policy, practice and governance. Nevertheless, care ought to be exerted extrapolating survey findings beyond the researched paramedics. To facilitate research replication, a copy of the survey instrument may be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

2.3. Policy Analysis of Strategic Plans and CPD Standards

The policy analysis answers three research questions using the methods described below:

- RQ6—What ANZ states/territories have current ES paramedicine policy?

- RQ7—Who is responsible for administering this policy?

- RQ8—How does current policy operationalize ES in paramedicine?

Policy analysis is an underutilized method, in part, because public policy is complex, poorly defined and misunderstood [12,24,25]. Research methods guiding public health policy analysis are limited and lack clear theoretical conceptualization of policy [12,24,26]. We begin addressing the absence of research analyzing the existence, and content, of ES policy guiding paramedicine training and practice, by undertaking document analysis of ANZ organizational policy. This is achieved through qualitative content analysis (QCA) methods. Utilizing Brown et al.’s [12] policy typology of analytical methods, we combine ‘mainstream’ and ‘interpretive’ orientations, expanding each beyond economic and/or political theory by incorporating sociological theory in considering values guiding policy priorities and governmentality/issue framing in conducting document analysis.

Policy analysis commenced by locating the key governing body for paramedic services in every ANZ state/territory (n = 10). An online search was undertaken of the governing bodies’ websites to obtain their most recent publicly accessible strategic plans. To identify if strategic plans contained ES policy, QCA [27] commenced by searching every strategic plan for the keywords ‘environment’, ‘sustainability’ and ‘footprint’ (i.e., carbon footprint). The search excluded incidences of financial sustainability, business sustainability, sustainable connection to community, workplace environment, safe environment and all other representations of ‘sustainability’ excluding ES. Second, standards relating to CPD from each of the two nationally governing bodies were searched for ES keywords. Third, all strategic plans and training policy applied QCA to identify contextualization of keywords, definitions for approved learning topics and CPD foci. The details (official websites, policy type, governing body) for all documents analyzed and cited in the results section appear in the reference list.

Several protocols were followed that critical QCA methods literature reviews suggest to optimize trustworthiness, reliability and validity [28]. Specifically, a complete sample was obtained, data were sourced from publicly available state government documents and results report verbatim document quotes within their corresponding strategic plan context to retain policy-makers’ original idea presentation. The former makes a particularly valuable contribution to policy analysis research because it avoids presenting or interpretating data out of context and allows international readers to self-determine data and results’ transferability [29]. Results bi-nationally detail: (a) what organizations have governance to formulate and oversee paramedicine policy; (b) which strategic plans include ES measures or goals; and (c) what policy is under revision.

3. Results

3.1. Survey Results

Eighty-six paramedics completed the survey. Demographically, 57% (n = 49) were female and 43% (n = 37) male. Only binary gender categories were selected, despite inclusion of non-binary gender categories in the research design. Age ranged from 20–59, with most under forty. Over 80% (n = 69) identified as Caucasian, 15% (n = 13) were first-generation immigrants (15%/n = 13) and 5% (n = 4) were indigenous Australians or New Zealanders. A Bachelor’s degree was the highest education achieved by most (73%/n = 63). Only one respondent had less than a Bachelor’s degree. Nine percent (n = 8) had graduate diplomas and 15% (n = 13) completed Master’s or PhD’s.

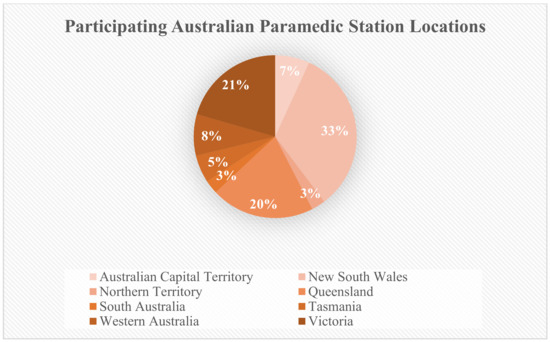

Paramedics worked across remote, rural, regional and metropolitan locations, with 87% (n = 75) living and working in Australia. Surveys were received from paramedics stationed in every Australian state and territory (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Geographical location of Australian participants’ workplaces.

Although not nationally representative, paramedics’ geographic location rates were consistent with national population distributions. Figure 1 shows NSW and Victoria, Australia’s two most populated and urbanized states, had the highest research participation. Participating paramedics largely were ‘new’ employees, with 74% (n = 64) employed less than 5 years at their current station, despite many being seasoned professionals with years of paramedic experience. A third (33%) of the sample were employed for over a decade in paramedicine, of which 23% (n = 20) worked for over sixteen years as paramedics. Current employment predominately occurred in the public healthcare sector (80%/n = 69), with some working across public and private healthcare systems (8%/n = 7).

Statistical analysis for RQ5 found paramedics failed to differ significantly for RQ1–4 by demographic factors, with the exception of ‘gender’. Nonparametric correlations (Spearman’s rho, two-tailed test) found moderately significant gender differences for individual interest in pursuing CPD in environmental education. Female paramedics showed greater interest and willingness to further their environmental education, indicating I would like to learn more about environmental issues (−0.296, p = 0.00, n = 86) and I would attend environmental sustainability training relevant to my profession if it was optional (−0.235, p = <0.05, n = 86), than male paramedics. Neither age, ethnicity, location, education, nor years in paramedicine accounted for this observed gender difference. Chi square tests comparing group means supported rejecting the null hypothesis 1, no gender difference in paramedics’ interest in learning about the environment: X2 (2, N = 86) = 9.692, p < 0.003. The null hypothesis of no gender difference in paramedics’ predicted attendance of professional environmental training, however, failed to be rejected because too few female paramedics would not attend training (n = 2), thus violating Chi Square assumptions of minimum (n = 5) cell count.

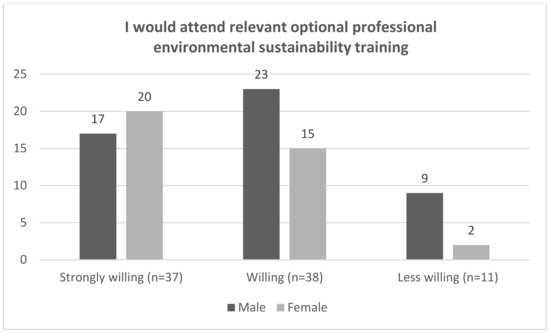

Whole sample results showed 84% (n = 72) of paramedics strongly agreed, or agreed, I would like to learn about environmental issues, demonstrating widespread positive response for RQ1. Only one respondent strongly disagreed and 15% felt neutral. Results for RQ2 show greater positive ES values, with 87% (n = 75) indicating willingness to attend optional, relevant professional ES training (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Paramedic willingness to attend environmental sustainability CPD.

Table 1 presents paramedics’ beliefs about professional environmental education to answer RQ3 and RQ4 which investigate paramedics’ beliefs about ES training.

Table 1.

Paramedics’ beliefs about ES education during training and CPD.

Compared with personal willingness to attend optional training, fewer (56%) thought paramedicine should include ES teaching within foundational paramedic training; 30% felt neutral and 14% opposed such training. More (73%) paramedics thought ES ought to be learned during CPD, rather than in higher education. Just 5% opposed environmental training throughout paramedic careers. No significant demographic differences emerged for such beliefs.

3.2. Policy Analysis

Data from document analysis of the most recent strategic plans from organizations responsible for providing paramedic service delivery to residents in every Australian State/Teritory and New Zealand answer RQ7. State/Teritory governments largely are responsible for paramedicine policy creation and administration. Paramedicine standards, responsibility for administering them, resides with the profession’s key body in each country. In Australia, this is the Paramedicine Board of Australia (PBA). PBA is overseen by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). Australian paramedicine’s CPD standards currently are under review, with existing standards published in 2018, with the 5-year planned currency cycle ending in 2023 [30]. The Paramedic Council of New Zealand (PCNZ) is responsible for setting and evaluating paradmedics’ registration requirements, including CPD. CPD to maintain registration centers on two PCNZ standards: i. Cultural safety and clinical competence and ii. Code of conduct [31]. Document analysis addresses RQ8 in the context of survey data findings answering RQ1–4. This is achieved by assessing if scope exists in relevant policies (RQ8) to facilitate CPD specifically (RQ4), or similar training (RQ2), for paramedics, relative to their interest in learning about ES (RQ1). To investigate if ES is included in ANZ paramedic service delivery and training (RQ6, What ANZ states/territories have current ES paramedicine policy?), Table 2 presents data about policy governance, ES policy and measurement and paramedics’ involvement, detailing where the State divulges policy responsibilty to other organizations, as identified in State/Territories’ strategic plans (left column).

Table 2.

Australia and New Zealand environmental sustainability strategic plan analysis, 2021–2028.

Exceptions to state governance exist in NZ’s capital city, Wellington, and its immediate area, which are served by the Wellington Free Ambulance, and Australia’s NT, which diverts responsibility to the global charity, St. John’s Ambulance Service who is government contracted to provide paramedic services. Thus, Table 2 data derive from St. John’s documents for Wellington and the NT, rather than government documents. Although St. John’s Ambulance operates in most states, their role is supporting some functions without being the agency responsible for ensuring paramedic service delivery.

Data answering RQ6 are found in the column titled ‘ES Mentioned’. ‘Yes’ connotes strategic plans contain the keyword ‘sustainability’ yet fail to provide a policy measure for its attainment. The existence, or absence, of ES policy illustrates a Durkheimian ‘social fact’ of ambiguity about the role pro-environmentalism plays in professional practice. ES institutionalization, its inclusion in formal social systems of governance in half (n = 5) of ANZ strategic plans governing paramedicine, evidences change from traditional government policy in pre-modern ANZ lacking ES codification.

If value agreement exists beyond policy creators cannot be determined by ES policy presence. What our policy analysis does reveal is the partiality of ES policy and an absence of paramedics’ engagement in all but one policy instrument researched: Queensland’s Strategic Plan. Whether this phenomena is due to systemic factors inhibiting/supporting paramedics’ participation in the policy-making process, or to (dis)interest lies beyond the scope of determination when utilizing publicly available policy documents.

Table 2 also details a minority (n = 4) of State/Territories’ strategic plans include measurable ES goals. This is consistent with UN [3] findings alerting a lack of definable, measurable ES goals to be slowing ES progression in timeframes recommended by urgent scientific research. Sociologically, the absence of concrete ES governance goals suggests de-prioritization of ES as a national value that is resourced and provided accountability measures. Value divergence manifests at a state level in Australia. Although no evidence of NZ effort to create distinct ES plans/policy was observed, two Australian states (Queensland and Western Australia) are undertaking ES policy creation.

Next, strategic plan data quotes are provided to answer RQ8, How does current policy operationalize ES in paramedicine? QCA of all strategic plans containing ES keywords reveals values consistent with pro-environmentalism. Aspiring to “Be a good corporate citizen for South Australia: our sustainability will not only focus on our financial and legislative compliance, but will include our social responsibilities and our environmental footprint” [33] (p. 15) shows social change by including ES, albeit fails to operationalize how that will be achieved through measurable outcomes in South Australia, a state not intending to create a separate ES plan. Ambulance Victoria also illustrated no plans to create unique ES policy, perhaps because its strategic plan contained measurable ES goals:

Outcome 3.3—our organisation is environmentally sustainable reducing our impact on the planet. By 2028—we have a business and operating model that enables us to reduce our waste and our environmental impact. This will involve us taking advantage of improvements to technology and sustainability practices across our operation. Indicators—environmental awareness and sustainability.[32] (p. 15)

A leader amongst the organizational plans analyzed, Ambulance Victoria [32] still does not specify how or what technological and sustainability practice improvements it will undertake, quantify ES or its reduced waste and environmental impacts. Further, with ES ‘awareness’ being the key indicator, there is need to specific how this will be accomplished. The ambition, “We will have an outstanding operating and governance model that is financially and environmentally sustainable” [32] also lacks policy operationalization detail regarding measurement towards achieving their ES goals:

(1) Reducing environmental impact: We will reduce our environmental impact by minimising waste, reducing energy consumption, and promoting environmentally friendly practices and assets. This can include initiatives such as using hybrid or electric vehicles, reducing paper usage through digital tools, and implementing recycling programs... (3) Trusted brand and stakeholder expectations: Sustainability is becoming increasingly important to stakeholders such as patients, employees, and the community. Demonstrating a commitment to sustainability, and exploring innovation in sustainable practice, we will improve our reputation and enhance trust from our community.[32] (p. 18)

Moreover, ‘sustainability’ is ambiguously defined:

Sustainability is a vital enabler for us as we reduce our environmental impact, develop new funded operating models, meet stakeholder expectations, and future proof our operations. Embracing sustainable practices and initiatives, we will become a more responsible and resilient organisation, through several ways.[32] (p. 18)

NSW Ambulance [34] (p. 10) also mentions ES in its policy, yet restricts discussion to three goals:

We are committed to delivering our services in a socially and environmentally sensitive way. Reducing our environmental and carbon footprint over time and delivering more environmentally sustainable health care through a focus on efficient energy and water usage and better waste management solutions.

Environmentally sustainable service delivery is operationalized as energy, water and waste efficiency, conceptually measurable as part of their ‘reduction’ goals, yet lacking measurability details.

Queensland, the only location to achieve every category in Table 2, operationalizes its ES policy, with the stated goal, “We will meet the threat of a changing climate through sustainable and socially responsible planning, resourcing and operations, and models of service tailored to the health care challenges posed by climate change”, achieved by:

Undertake[ing] research in partnership with key government, industry and academic partners, measuring the impacts of extreme climate conditions on emergency health services, to inform future planning and response models. Develop a staff-led environmental sustainability program to explore new ways of working sustainably and ensure the QAS is taking strong action on climate change. Develop a QAS Climate Action Plan to align with Queensland Government and other Queensland Health priorities.[35] (p. 42)

Consistently, ES lacks clear policy definition and measurement details, although goal achievement could be measurable.

Western Australia, which has plans to create separate ES policy, claims, “The Western Australian ambulance system is sustainable, meaning that there is capacity to provide ambulance services into the future by... minimising or eliminating damage to the environment” [36]. No ES operationaliztion or measurement detail is provided, albeit policy further directs, “Ambulance service organisations develop an environmental management system to monitor and improve environmentally sustainable practices, including implementing strategies for minimising or eliminating negative environmental impacts arising from emissions to air, land and water” [36].

Finally, St. John New Zealand’s [39] (p. 11) ES policy goals include carbon reduction in “transport, property, waste, procurement, and supply chains”, with two clearly operationalized and measurable goals, carbon-reduced certification and net-carbon zero progression:

In all we do there is the responsibility to transition toward more sustainable practices and reduce our environmental impact. Kaitiakitanga is about guardianship and protection of the environment and natural resources for future generations and sustainable health. Over the next five years our environmental strategy will guide understanding of our carbon footprint and reduce the environmental burden in transport, property, waste, procurement and supply chains. Our short-term goal is to be carbon reduced certified and progress towards becoming net carbon zero in the future.

ES is defined following UN principles, illustrating value alignment with global ES goals that are explicitly stated, with accountability potential. As such, it appears the most ES committed organization. Whether this reflect different national ES paramedicine values lies beyond the scope of this analysis. Nevertheless, it highlights the relevance clear, systemic ES goal articulation and measurement for ES progression may have, as Durkheimian theory communicates, for shaping societal norms and values that affect individual beliefs and individualized practices.

No ES policy was found for the ACT, NT or Tasmania, so it remains unknown if or how ES in paramedicine is governed or operationalized in practice and/or training.

Finally, a bi-national comparison of CPD policy standards in Table 3 evidences the absence of ES.

Table 3.

CPD standards for Australia and New Zealand.

Despite current absence, scope exists for ANZ paramedicine CoC and CPD standards to incorporate ES using PBA’s and PCNZ’s existing policy framework. PBA standard 2, “Draws on the best available evidence, including well-established and accepted knowledge that is supported by research where possible, to inform good practice and decision-making” is consistent with UN sustainability goals [2,3] for environment and education. Similarly, Durkheimian theory [21] and global plans [3] suggest societal agreement regarding the social fact that environmental and human health are global needs driven by sustainability values. Fostering value alignment in ES policy and practice may occur through PCNZ’s CoC standard 2, “Identify and respect the cultural needs and values of health consumers”, whereby CPD is expanded to include how the paramedicine profession’s environmentally degrading actions detract from health consumers’ ES values and needs. If current training frameworks applied a Durkheimian [21], rather than economic or psychological understanding of individualism [20], considering the role of sociopolitical structures play in shaping seemingly ‘autonomous’ value construction of ES beliefs, then the interdependence of socio-physical environments and employees could be better understood and negotiated.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

It is long established that modernization changes natural and social environments through urbanization processes. Tönnies (1887) [43] theorized the societal change from traditional to modern, urbanized society produced heightened individualism through a loss of traditional ‘community’. Classically, this social change surpasses individual psychology; the problems facing modernity reflect deep, fundamental change in the organization of society and communities that affect collective norm, belief and value construction. Hence, creating institutional/organizational environmental policy, as a mechanism to effect global and local EP, requires systemic change of norms and values, beyond individual repudiation of environmental ‘facts’.

Contemporary, largely economic, theorization perceives individualism as a cultural principle understanding individuals’ values, identity and behavior to be autonomous and self-guided, irrespective of sociopolitical structures [44]. Contrastingly, Durkheim’s (1895) [45] classic sociological theory explicates ‘solidarity’ exists where individuals share similar beliefs and values, and are interdependent in having needs fulfilled, such as through service provision. Despite contemporary dismissal of Durkheimian theory as failing to accommodate individual agency and subjectivity, European cultural sociology [46] (p. 419) clarifies misconceptualizations, explaining:

Durkheim argues that individualism should not be equated with utilitarianism or egoism. The proposed alternative bears a remarkable resemblance to the categorical imperative of Kant: we should not base our actions on singular interests, but on what we share as human beings, our value as being human in abstracto [45] (p. 5)... The value of individualism produces social cohesion in a society that searches for meaning within an inner-worldly view: ‘It is a religion in which man is at once the worshipper and the God’ [45] (p. 46). Just like religion, individualism constitutes a whole made up of ideas and values that create social order.

Our research design advocated Durkheim’s theorization of individualism may facilitate understanding contemporary ES practices in ANZ paramedicine, manifested as paramedics’ beliefs and institutionalized policy goals for ES training created by paramedic organizations. Addressing environmental degradation from paramedic practice requires policy and practice supporting environmental health values consistent with global UN goals for ES progression. Applying mixed methods, we explored individual and institutional beliefs about paramedicine ES teaching/learning through online surveys and policy analysis.

The research found paramedics surveyed are highly interested in, and willing to, undertake further ES training, albeit are trained and employed in social institutions (universities and workplaces) where ES education fails to formally exist either in professional training for paramedic registration, or during their careers as part of CPD. Despite urgent global calls, supported by scientific research, for changed ES practice and accountability to reduce worldwide environmental problems transcending localized geographies [3], results suggest decentralization [4] of laws, governance and policy remain macro-level challenges to promoting national, let alone global, pro-environmentalism.

To further a global, multi-disciplinary literature dominated by economic and psychological theories about attitudes driving individual environmental behaviors [4,5,6,7], this article contributed a sociological investigation positing need to consider the role professional policy (which results found are orchestrated by ANZ State/Territory governments and their appointees) plays in shaping paramedicine’s operationalization of ES goals, their measurement and ES’ (de)prioritization in paramedic training/CPD and practice. Results further international research arguing the urgency for enhancing paramedicine CPD curriculum and cultivation of a professional culture better aligned with sustainability measures [9,10], given ANZ CPD standards and codes-of-conduct exclude ES. With global reporting of education being “in deep crisis” [3] and unsuitable to create employees able to tackle EP [5], as paramedics increasingly are front-line responders to environmental crises [9,10], ES exclusion in formal training and CPD requires urgent attention, without a ‘full curriculum’ further justifying the status quo of ES exclusion [12]. Our results contribute empirical evidence that the majority (84%) of practicing paramedics surveyed would like to learn about environmental issues, with only one respondent unwilling. Further, statistics shows this willingness does not demographically vary, with the exception of gender.

Our findings that female paramedics were more interested in, and willing to undertake, ES training contradicts other organizational research in Scotland [47], India and Poland [48]. Traditionally, paramedicine in ANZ was a masculine occupation. Gender-based harassment and bullying in the two largest jurisdictions prompted official government investigations [49]. Sociological research of Australian women in traditionally male-dominated fields notes the importance of acquiring culture capital, particularly education/training for career development and success, to assuage perceived gender (e.g., physical strength and emotional resilience) and/or social capital (social network exclusion) difference relative to work roles [50]. Why female paramedics expressed greater interest/willingness in ES learning/training warrants further investigation, as does identifying the parameters of ES educational content more broadly.

The limited research available about Australian paramedics consistently notes tertiary-trained paramedics value research and evidence-based practice, appreciating the intentions behind professional obligations linked to CPD and more effective system navigation [51]. Our findings further this research, with 75% of surveyed paramedics expressing willingness to attend ES training if it were offered, and 24% feeling ‘neutral’. High willingness, in a systemic environment of mandatory CPD since 2018 for national registration as a profession, illustrates an institutionalized value of furthering knowledge. Further, the formalization of CPD shows historical change since 2018 where its value was highly dependent on local managerial attitudes [51]. Hence, broader societal changes regarding ES’s value, organizational ES goals found in our policy analysis and the value of CPD in paramedicine specifically, provide an optimistic content whereby individual beliefs, expressed willingness and policy frameworks align with broad global values and goals to introduce ES education/training. Given the limitations of our survey, specifically its non-representative sampling framework, we recommend conducting nationally representative surveys in ANZ, and beyond, to identify if the ES willingness observed in our study is consistent across the sector’s population.

Policy intentions for improving the ANZ ambulance sector’s ES, however, outweigh tangible progress. The Council of Ambulance Authorities (encompassing Australia, NZ and Papua New Guinea) demonstrated commitment in its five year strategic plan (2023–2028) to carbon emission reduction, waste management and reusable energy initiatives. Uncertainties linger regarding educational commitments extending beyond patient care that encompass planetary health goals [52]. Our policy analysis suggests including ES training/CPD would facilitate staff engagement and, thus, increase the likelihood of reaching ES targets, thereby progressing organizational and international goals. NSW Health, responsible for healthcare systems in Australia’s most populous state that services 30.6% of the country’s population [53], included ES staff education in its Future Health Plan for 2022–2032 [54] goal to “adopt a more environmentally sustainable approach for our health service” [54] (p. 53). As one of thirty objectives, however, their ES objective made no mention of training-related indicators, such as staff engagement [54], to achieve their objective.

Ambulance services’ contribution to sector-wide plans focused on efficient energy, resource use and waste management in objectives to “deliver our services in a socially responsible way” [34] (p. 10), without mention of ‘environmentally responsible’ service delivery. This single strategy appeared amongst 54 listed across 16 objectives and 4 priorities [34]. The strategic plan of Australia’s second largest ambulance service, in Victoria, listed ‘sustainability’ as one of its four key areas. Although ‘sustainability’ was applied broadly, the plan included ‘increase in environmental awareness’ as one indicator of success, which, along with commitment to assisting staff to create “personalized career pathways” [32] (p. 25), utilized internal/external and formal/informal development pathways. This QCA evidences opportunities for ES-focused CPD training could be supported through existing ANZ healthcare provider policy. Nevertheless, the specifications of how and when this could be implemented require further consideration given the limitations of the present analysis.

While strategic plans of paramedicine organizations in Australasia increasingly incorporate environmental and sustainability initiatives, the lack of clear outcomes and measures related to staff engagement and training poses challenges (Table 2). This raises concerns about the potential loss of gains that could be realized from societal change in pro-environmental, collective values. Specifically, new graduates, shaped by a more environmentally aware society, will assimilate into workplaces characterized by a preference for local organizational culture, over official policies and practices outlined in strategic plans [49]. Workplace culture, marked by the risk of career implications for complaints against colleagues [49], and dogmatic beliefs resistant to change [8], may hinder the critical, innovative spirit of new graduates interested in supporting greener health initiatives. Well-crafted ES training programs, particularly those with potential for cascading effects beyond workplace behaviors, have been found to enhance job satisfaction [55]. Most survey respondents expressed a desire to learn about ES, with disparity only existing over ‘where’ such learning would best occur; 73% thought during paramedic careers, compared with 56% during paramedicine training. These results suggest it is timely to capitalize on ES interest, addressing dissenting beliefs through clear linkage to policy-makers’ ES objectives and the perceived practical benefits research suggests are worthwhile [9]. As Maine and Anderson [56] identified in their international systematic review of health practitioners, CPD training with outcomes communicated important by targeted professionals are more effective than those that practitioners may consider unimportant [56]. This underscores the importance governmentality and governance systemically play to influencing individual behavior and value expression.

Sociologically, Cortois [46] explains, “... how individuals are socialised into an individualist culture. If we are dealing with shared values here, there must be a learning process that inculcates inclusion in this value system”. In the current system, ANZ paramedics are required to self-manage completing 30 CPD hours annually, recording in a portfolio or similar for provision upon request. Within this time, Australians must include 8 h of interactive sessions with other practitioners and New Zealanders 3 h of cultural safety-related topics. Our findings (Table 3) showed current standards for approved CPD focus on maintaining professional competence, building existing knowledge, utilizing current research to inform decision-making and good practice, and improving skill competencies. Both national paramedic councils provide CPD opportunities (e.g., talks, conferences) and opportunities from approved providers of online courses and workplace activities. Incorporating ES training in this framework would align with our survey respondents’ preferences and avoid systemic challenges regarding higher-education curriculum [12].

Individual practitioners seeking to enhance their ES literacy, as part of CPD, could presently align such activity using PBA standard 2: “Draws on the best available evidence, including well-established and accepted knowledge that is supported by research where possible, to inform good practice and decision-making” [41]. If ‘good practice’ is more broadly defined to include consideration of planetary health, the concept increasingly adopted by health sectors and professionals globally [7], ES in paramedicine may come to encompass the ‘interdependency’ of human and non-human environments. Holistic understanding may include the biological and social [57], embracing the concept understood by First Nation Australians as ‘Country’, and characterizing a value the Durkheimian concept of interdependence explicates. Indeed, scope already exists to align such ES conceptualization in existing policy frameworks with operational goals. For PCNZ, growing ES interest and aligned values training fits CoC 2: “Identify and respect the cultural needs and values of health consumers” [42]. Failure to align CPD activity with approved criteria risks registration and employment. Given the sector-wide need to clarify ES definitions, goal measurements and knowledge requirements to achieve organizational objectives, we recommend CPD as an opportune space to commence such ideological and practice work.

Practically, the social practice theory-based framework developed by Omer and Roberts [58] considers contextual factors affecting sustainability practice implementation by focusing on behavior changes not contingent on individual ES attitudes. Taking an organizational value approach aligned with UN sustainability goal [2] achievement we have advocated throughout this article, operationalized through CPD by aligning ES training within existing organizational governance and policy frameworks, may help develop suitable, relevant, engaging resources most likely to lead to practice changes that progress the sector’s larger goals. Organizations can link ES goals, values and practical outcomes. For example, the value of ‘improving ES’ with the goal of ‘reduced carbon footprint’ and the practice of ‘increasing electric vehicles’ as part of clear protocols. Ideally, this would be supported by CPD ES training around energy consumption. Our research found four Australian states and New Zealand are positioned to do this, because their strategic plans include clear ES outcomes, albeit only Queensland’s plan involves staff to meet targets (Table 2). This uniquely positions Queensland for sector-wide leadership since changes in staff training, linked to ES outcomes, align with organizational policy priorities. Nevertheless, NSW, Victoria and NZ could modify their policy, and forge ahead as sector leaders in ES training and goal achievement, if desired.

In December 2023, the Commonwealth of Australia unveiled its National Health and Climate Strategy, a comprehensive initiative designed to instigate transformative change at the national level, involving collaboration across various state sectors. A primary strategy objective is the health sector’s systematic decarbonization [59]. A pivotal aspect of plan implementation involves bolstering workforce capabilities, wherein an emphasis is placed on integrating components into the accreditation process for undergraduate courses and CPD programs [59]. Although the articulated strategy falls short of the mandatory training requisites observed in the UK [11], juxtaposed with recent state-based plans for the ambulance sector, it elucidates a discernible trajectory; Individuals aspiring to advance in healthcare must possess both the capacity and willingness to assume leadership roles for ES and climate health [59]. Our respondents are not statistically representative of ANZ paramedics. Nevertheless, results evidence a substantial cohort of paramedics exists, and may be poised to contribute actively to decarbonization imperatives in the health sector. Future research and action ought to build upon this finding. Identifying and supporting such professionals to become instrumental leaders in formulating and executing initiatives arising from the inaugural National Health and Climate Strategy has national, and global, benefits. What remains is for the regulatory bodies, namely the APC and PCNZ, plus individual State/Territory-based paramedicine authorities, to catchup with wider discourse affecting professional ES practice and safeguarding the planet for tomorrow’s ‘health customers’.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, and writing original draft, A.T.R. and A.C.; SPSS data entry and analysis, A.T.R.; Policy data curation and analysis, A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Charles Sturt University (protocol #H21065, April 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Survey data supporting reported results is unavailable for public access and stored at Charles Sturt University following ethics compliance. Policy data supporting reported results is publicly available on the websites provided in the reference list.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Verwiebe, R. Social Institutions. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 6101–6104. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- United Nations. Global Sustainable Development Report (GSDR) 2023. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/gsdr/gsdr2023 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Smith, Z.A. The Environmental Policy Paradox, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, E.C.; Centeno, D.; Todd, A.M. The role of climate change education on individual lifetime carbon emissions. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0206266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jodi, D.S.; Cassandra, L.T.; Andrea, J.M.; Matthew, J.E.; Robert, D.; Harriet, W.H.; Robert, S.L.; Joseph, B.; Anthony, C.; Forbes, M.; et al. The Green Print: Advancement of Environmental Sustainability in Healthcare. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.E.; Madden, D.L. The evolving call to action for including climate change and environmental sustainability themes in health professional education: A scoping review. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2023, 9, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allum, P. Investigating Opportunities for Sustainability Behaviours within Paramedic and Ambulance Service Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfati, M.; Lefébure, A.; Harpet, C.; Baurès, E.; Marrauld, L. Is environmental sustainability training fundamental to healthcare leadership? State of the art with health students and health leaders. Manag. Healthc. 2023, 8, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Radkova, M.; Stefanova, K.; Uzunov, B.; Gärtner, G.; Stoyneva-Gärtner, M. Morphological and Molecular Identification of Microcystin-Producing Cyanobacteria in Nine Shallow Bulgarian Water Bodies. Toxins 2020, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtue, G.; Ragusa, A.T.; Crampton, A. Recycling attitudes, behaviours, and environmental policy in Australian and New Zealand paramedicine. Aust. Paramed. 2023; Autumn. 15–21. Available online: https://www.ausparamedic.com.au/3d-flip-book/autumn-2023/ (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Browne, J.; Coffey, B.; Cook, K.; Meiklejohn, S.; Palermo, C. A guide to policy analysis as a research method. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackmore, J.; Lauder, H. Researching Policy. In Research Methods in the Social Sciences; Somekh, B., Lewin, C., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arnon, S.; Orion, N.; Carmi, N. Environmental literacy components and their promotion by institutions of higher education: An Israeli case study. Environ. Edu. Res. 2015, 21, 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, K.Y.H.; Kozar, J.M. Sustainability knowledge and behaviors of apparel and textile undergraduates. Int. J. Sust. Higher. Ed. 2012, 13, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedi, A.; La Barbera, F.; De Jong, A.; Rollero, C. Intention to adopt pro-environmental behaviors among university students of hard and soft sciences: The case of drinking by reusable bottles. Int. J. Sust. Higher. Ed. 2021, 22, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, Á.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Putting the human back in “human research methodology”: The researcher in mixed methods research. J. Mix. Method. Res. 2010, 4, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Reseach Method; Pearson: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, M.A.; Chantler, T. Principles of Social Research; McGraw-Hill Education (UK): London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, C.; Yu, F. Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. J. Mix. Method. Res. 2007, 1, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J. Qualitative Researching, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.A.; Weible, C.M. (Eds.) Theories of the Policy Process, 3rd ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, B.G. Advanced Introduction to Public Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, B.G.; Zittoun, P. Contemporary approaches to public policy. In Theories, Controversies and Perspectives; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative Content Analysis:A Focus on Trustworthiness. Sage Open 2014, 4, 2158244014522633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paramedicine Board. Professional Capabilities for Registered Paramedics. 2021. Available online: https://www.paramedicineboard.gov.au/Professional-standards/Professional-capabilities-for-registered-paramedics.aspx (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Paramedic Council of New Zealand. Professional Development. Available online: https://paramediccouncil.org.nz/PCNZ/PCNZ/4.Resources/Professional-development-.aspx?hkey=5f6e2148-db68-4cf1-b1a8-6132247361ba (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Ambulance Victoria. Strategic Plan 2023–2028; Victoria Health: Blacktown, NSW, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- SA Ambulance Service. Strategic Plan 2023–2027. 2023. Available online: https://saambulance.sa.gov.au/about-us/strategic-plan-2023-2027/ (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- NSW Ambulance. Strategic Plan 2021–2026. 2021. Available online: https://www.ambulance.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/648578/NSW-Ambulance-Strategic-Plan-2021-2026.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Queensland Ambulance. Queenslnd Ambulance Service Strategy 2022–2027. 2022. Available online: https://www.ambulance.qld.gov.au/docs/QAS-Strategy.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Government of Western Australia. Amblance Services Western Australia: A Framework for Statewide Ambulance Service Operations. 2021. Available online: https://www.health.wa.gov.au/Reports-and-publications/Ambulance-service-operations-framework (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Tasmanian Government. Department of Health Strategic Priorities 2021–2023. 2021. Available online: https://www.health.tas.gov.au/about/what-we-do/strategic-programs-and-initiatives/department-health-tasmania-strategic-priorities-2021-2023 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- ACT Government. Strategic Plan 2024–2025; ACT Government: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- St John New Zealand. Manaaki Ora: Our Strategy 2022–2027; St John: Auckland, New Zealand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wellington Free Ambulance. Wellington Free Ambulance 2030. 2023. Available online: https://www.wfa.org.nz/about-us/our-strategy (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Paramedicine Board of Australia. Registration Standard: Continuing Professional Development. 2018. Available online: https://www.ahpra.gov.au/Registration/Registration-Standards/CPD.aspx (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Paramedic Council of New Zealand. Code of Conduct. Available online: https://www.paramediccouncil.org.nz/common/Uploaded%20files/Standards/220422%20Code%20of%20Conduct%20A5%20Spread%20-%20Website.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Tönnies, F. Community and Society (1887); Harper & Row: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1984; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. The Rules Of Sociological Method. In Readings from Emile Durkheim; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Cortois, L. The myth of individualism: From individualisation to a cultural sociology of individualism. Eur. J. Cult. Political Sociol. 2017, 4, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnington, A.; Aldabbas, H.; Mirshahi, F.; Pirie, T. Organisational development programmes and employees’ career development: The moderating role of gender. J. Workplace Learn. 2022, 34, 466–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupczyk, T.; Gross-Gołacka, E.; Kubicka, J. Training employees in sustainability and assessing their ability to implement bottom-up changes in companies for the green revolution: A comparative analysis in Poland and India. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2023, 26, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, A.; Stack, H.; Maria, S.; Bridges, D. 13 Paramedicine and workplace sexual harassment. In Gender, Feminist and Queer Studies: Power, Privilege and Inequality in A Time of Neoliberal Conservatism; Bridges, D., Lewis, C., Wulff, E., Litchfield, C., Bamberry, L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, D.; Bamberry, L.; Wulff, E.; Krivokapic-Skoko, B. “A trade of one’s own”: The role of social and cultural capital in the success of women in male-dominated occupations. Gend. Work. Organ. 2022, 29, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A. Australian Paramedic Understanding of the Purpose of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) and Mandatory CPD Requirements; Charles Sturt University: Bathurst, NSW, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- The Council of Ambulance Authorities. Strategy 2023–2028. 2023. Available online: https://issuu.com/firstbycaa/docs/caa_first_magazine_winter_2023_/s/29037240 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. New South Wales: 2021 Census All Persons Quickstats. 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/1 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- NSW Ministry of Health. Future Health: Guiding the Next Decade of Care in NSW; NSW Ministry of Health: St Lenords, NSW, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pinzone, M.; Guerci, M.; Lettieri, E.; Huisingh, D. Effects of ‘green’training on pro-environmental behaviors and job satisfaction: Evidence from the Italian healthcare sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, P.A.E.; Anderson, S. Evidence for continuing professional development standards for regulated health practitioners in Australia: A systematic review. Hum. Resour. Health 2023, 21, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.; Walpole, S.; McLean, M.; Alvarez-Nieto, C.; Barna, S.; Bazin, K.; Behrens, G.; Chase, H.; Duane, B.; El Omrani, O.; et al. AMEE Consensus Statement: Planetary health and education for sustainable healthcare. Med. Tech. 2021, 43, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omer, Y.; Roberts, T. A novel methodology applying practice theory in pro-environmental organisational change research: Examples of energy use and waste in healthcare. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130542–132022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commonwealth of Australia. National Health and Climate Strategy. 2023. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/national-health-and-climate-strategy (accessed on 12 March 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).