Sustainable Development of Platform Enterprises: A Synthesis Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

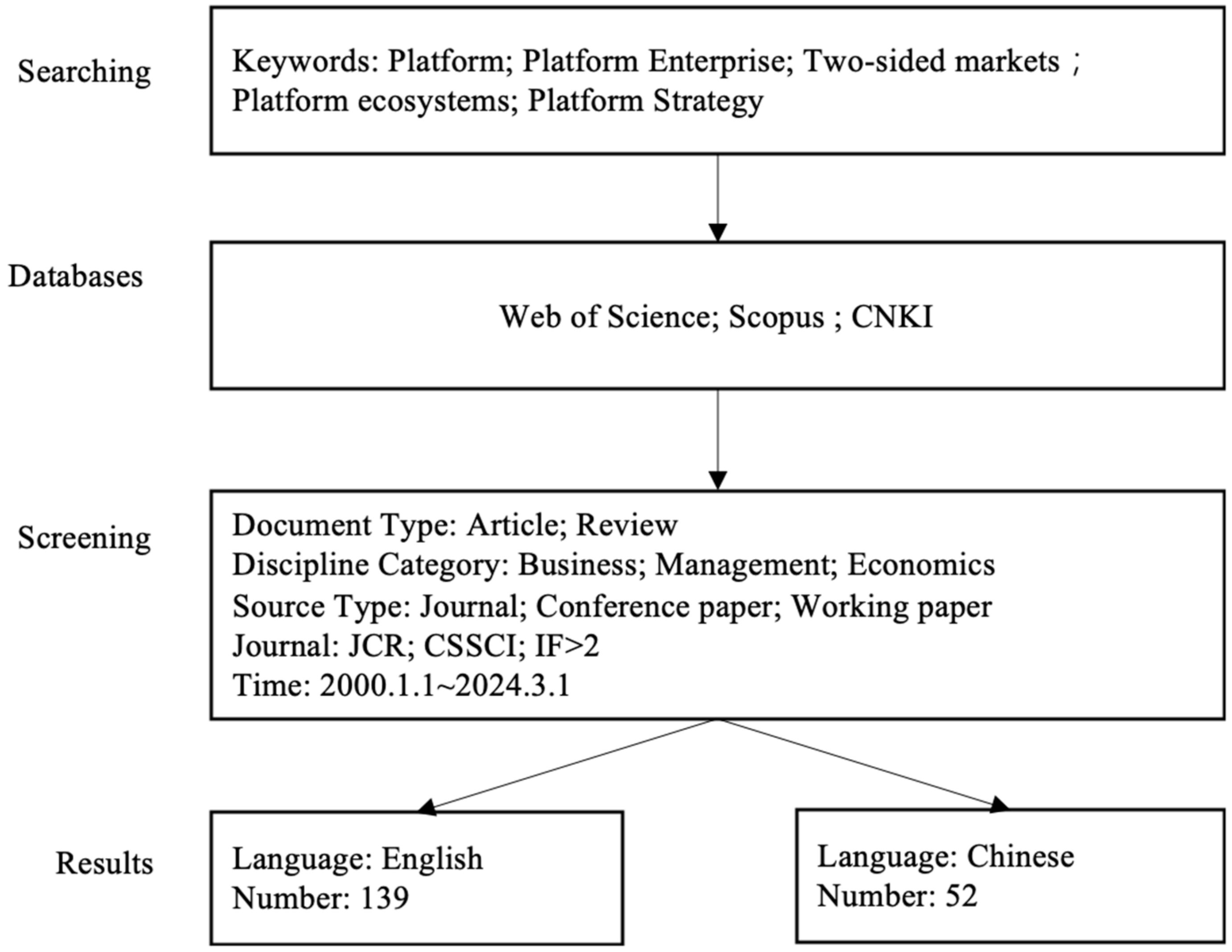

2. Research Methodology

3. Challenges and Strategies of Platform Enterprises at Different Growth Stages

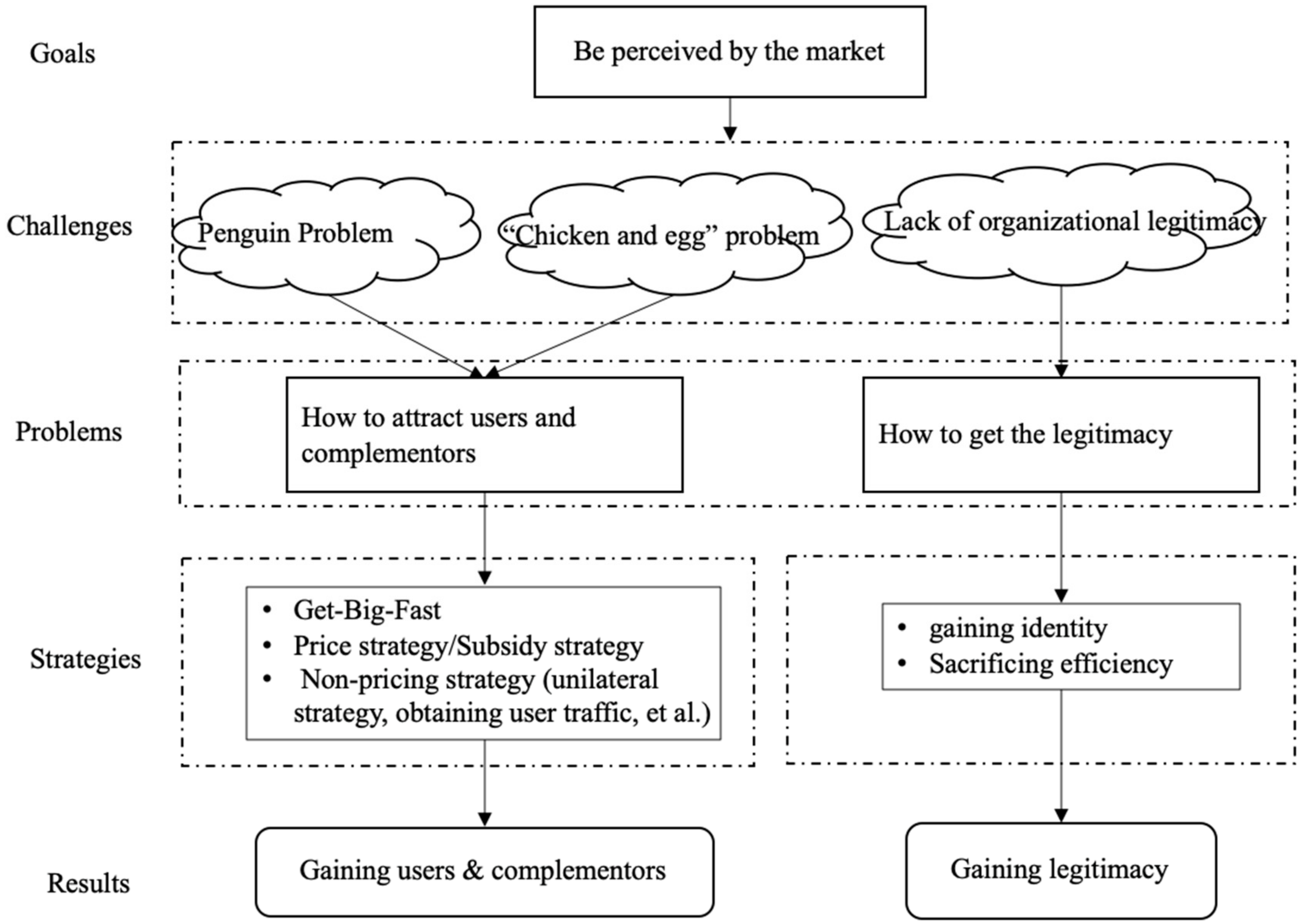

3.1. The Birth Stage

3.1.1. Platform Challenges

3.1.2. Platform Strategy

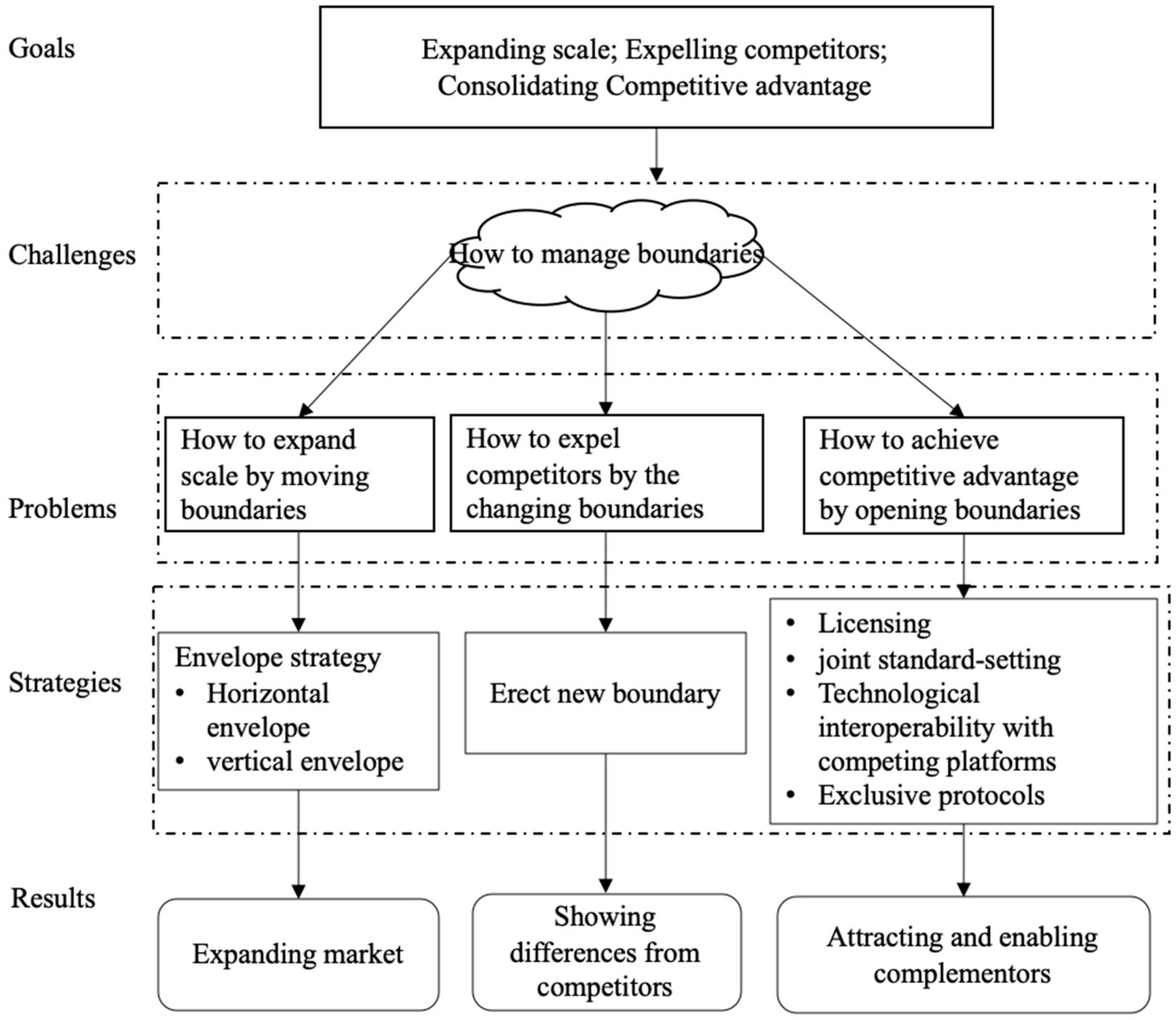

3.2. The Expansion Stage

3.2.1. Platform Challenges

3.2.2. Platform Strategy

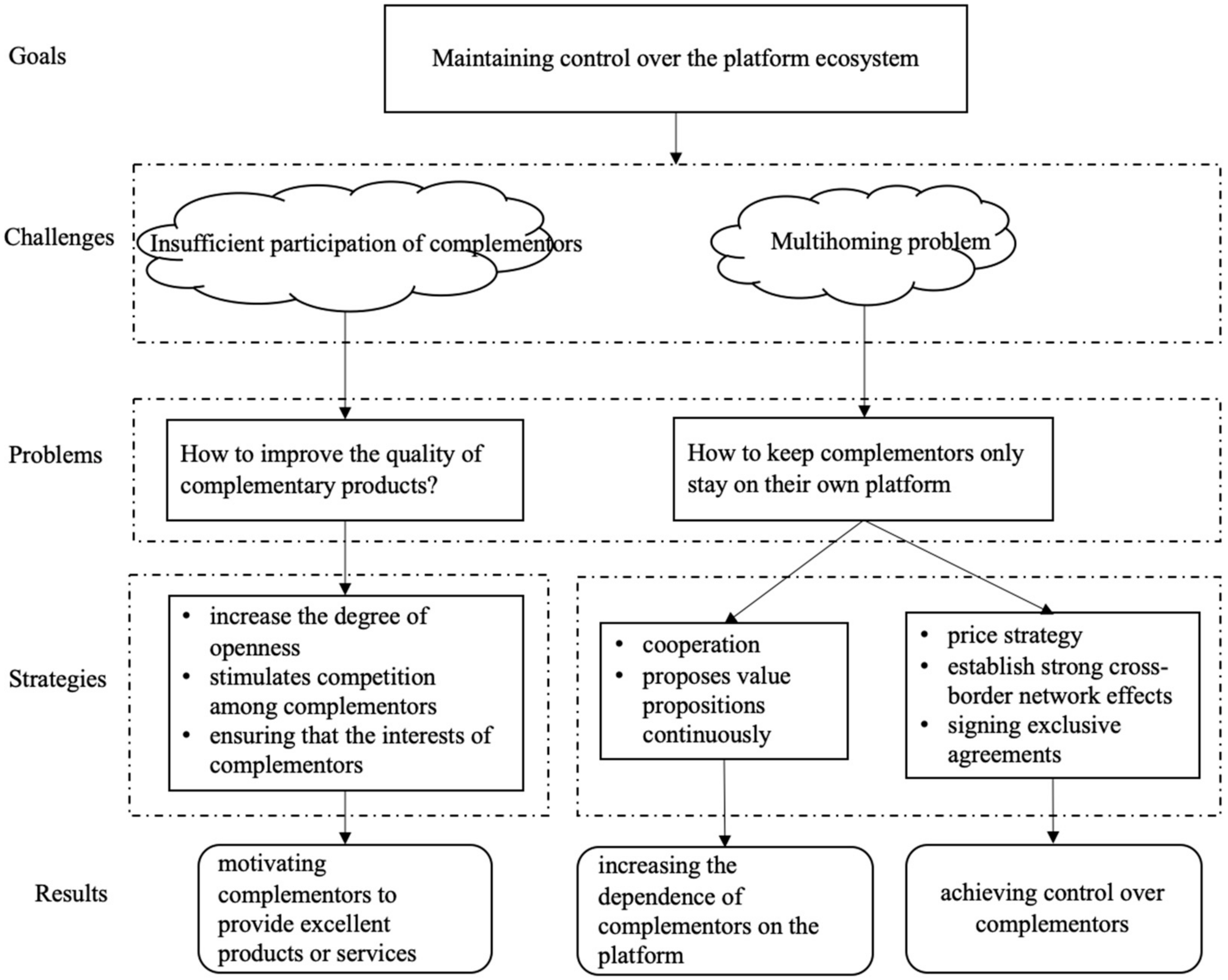

3.3. The Leadership Stage

3.3.1. Platform Challenges

3.3.2. Platform Strategy

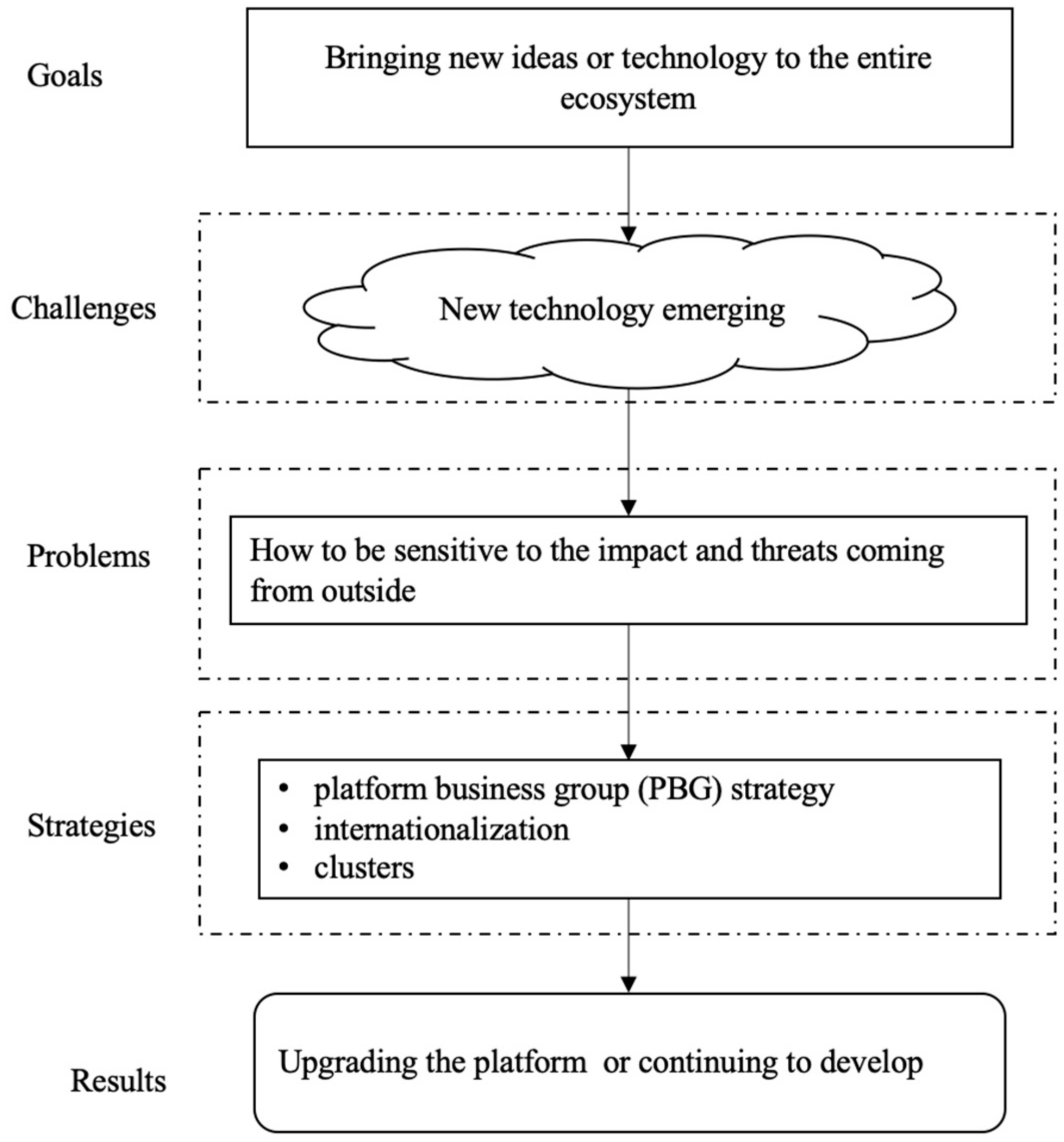

3.4. The Self-Renewal Stage

3.4.1. Platform Challenges

3.4.2. Platform Strategy

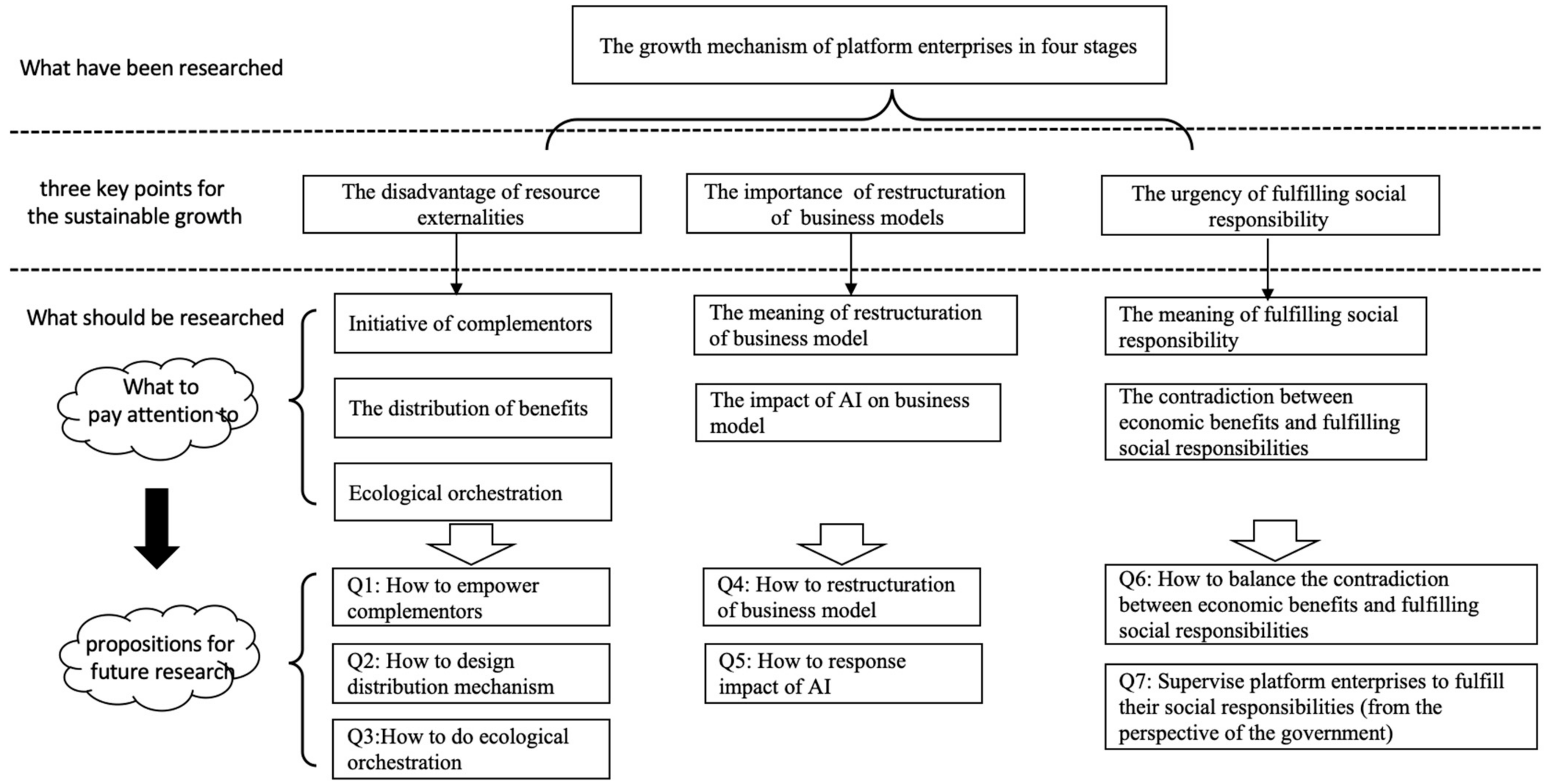

4. Sustainable Growth of Platform Enterprises

4.1. How to Resolve the Disadvantage of Resource Externalities

- Q1: How can platform enterprises empower complementors and encourage them to innovate from a win–win perspective?

- Q2: How can reward and punishment and distribution mechanisms be designed and optimized based on the principle of encouraging complementors?

- Q3: What is the difference between ecological orchestration and resource orchestration, and how can platform enterprises mobilize the enthusiasm of complementors through ecological orchestration?

4.2. How to Restructure a Sustainable Business Model

- Q4: How can a platform’s business model be restructured to gain momentum for sustainable development?

- Q5: How are business models affected by the development of information technology? How will AI affect platform business models? How will AI promote value creation?

4.3. How to Fulfil Social Responsibility

- Q6: From the perspective of platform enterprises, how can the contradiction between economic benefits and fulfilling social responsibilities be balanced? How can social responsibility be fulfilled better by reforming business models and adopting new technologies?

- Q7: From the perspective of the government, how can the motivation of enterprises to fulfill their social responsibility be stimulated and how can they be supervised to fulfill their responsibilities?

5. Conclusions

5.1. Contributions

5.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Astyne, M.V.; Parker, G.G.; Choudary, S.P. Pipelines, platforms, and the new rules of strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 94, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bouaau, K.J.; Jeppesen, L.B. Unpaid crowd complementors: The platform network effect mirage. Strat. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1761–1777. [Google Scholar]

- Iansiti, M.; Levien, R. The Keystone Advantage: What the New Dynamics of Business Ecosystems Mean for Strategy, Innovation, and Sustainability, 1st ed.; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ozalp, H.; Cennamo, C.; Gawer, A. Disruption in platform based ecosystems. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 1203–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A.; Cusumano, M.A. How companies become platform leaders. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2008, 49, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Tan, C.; Jiang, S. The Steering-wheel model of platform leadership achievement: A case study of Li & Fung. China Indus. Eco. 2015, 1, 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Gawer, A.; Henderson, R. Platform owner entry and innovation in complementary markets: Evidence from Intel. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2007, 16, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strat. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenmann, T.R.; Parker, G.; Alstyne, M.V. Platform envelopment. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 1270–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwana, A. Platform Ecosystems: Aligning Architecture, Governance, and Strategy, 1st ed.; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: Burlington, VT, USA, 2013; pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cennamo, C.; Santalo, J. Platform competition: Strategic trade-offs in platform markets. Strat. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1331–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Lee, J. Reconsideration of the Winner-take-all Hypothesis: Complex networks and local bias. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1838–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afuah, A. Are network effects really all about size? The role of structure and conduct. Strat. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Cenamor, J.; Parker, G.; Alstyne, M.V. Unraveling platform strategies: A review from an organizational ambidexterity perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcintyre, D.P.; Srinivasan, A. Networks, platforms, and strategy: Emerging views and next steps. Strat. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Iansiti, M. Entry into platform-based markets. Strat. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visnjic, I.; Cennamo, C. Towards an integrated perspective on platform market competition. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proceed. 2013, 1, 16837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R.H. The nature of the firm. Economica 1937, 4, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A. What drives shifts in platform boundaries? An organizational perspective. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proceed. 2015, 1, 13765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leong, C.; Pan, S.L.; Leidner, D.E.; Huang, J.S. Platform leadership: Managing boundaries for the network growth of digital platforms. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2019, 20, 1531–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Van Alstyne, M.V.; Choudary, S.P. Platform Revolution, 1st ed.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Tong, T.W. Platform Governance Matters: How Platform gatekeeping affects knowledge sharing among complementors. Strat. Manag. J. 2020, 43, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentelsaz, L.; Garrido, E.; Maicas, J.P. Incumbents, technological change and institutions: How the value of complementary resources varies across markets. Strat. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1778–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotari, P.; Järvi, K.; Kortelainen, S.; Huhtamäki, J.; Phillips, F. Winner does not take all: Selective attention and local bias in platform-based markets. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 114, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavalaei, M.M.; Cennamo, C. In search of complementarities within and across platform ecosystems: Complementors’ relative standing and performance in mobile apps ecosystems. Long Range Plan. 2021, 54, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazawneh, A.; Henfridsson, O. Governing third-party development through platform boundary resources. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), St. Louis, MO, USA, 12–15 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, T. Study on the labor relations in the new use of labor forms under the background of sharing economy: Taking Didi as an example. J. Shandong Youth Univ. Polit. Sci. 2017, 1, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J. A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisani, N.; Kourula, A.; Kolk, A.; Meijer, R. How global is international CSR research? Insights and recommendations from a systematic review. J. World Bus. 2017, 52, 591–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic Capabilities and (Digital) Platform Lifecycles; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017; pp. 211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Gawer, A.; Phillips, N. Institutional Work as Logics Shift: The Case of Intel’s Transformation to Platform Leader. Organ. Stud. 2013, 34, 1035–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseid, A.; Johnson, N.L. Platform Monopolies, 1st ed.; Yang, F., Ed.; China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, N.; Wang, J.; Yang, D. Platform envelopment strategy decision and competitive advantage building under the background of industrial convergence—A case study of ZDM. China Indus. Econ. 2015, 5, 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, J.; Saloner, G. Installed base and compatibility: Innovation, product preannouncements and predation. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986, 76, 940–955. [Google Scholar]

- Caillaud, B.; Jullien, B. Chicken & egg: Competition among intermediation service providers. Rand J. Econ. 2003, 34, 309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Noe, T.; Parker, G. Winner take all: Competition, strategy, and the structure of returns in the Internet economy. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. 2005, 14, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yu, Z. Platform Strategy: A Global Business Model Revolution, 1st ed.; Zhongxin Press: Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 18–69. [Google Scholar]

- Caillaud, B.; Jullien, B. Competing cybermediaries. Euro. Econ. Rev. 2001, 45, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Lin, Q. Research on the construction and evolution of resource management capability of platform enterprises: A double-case study based on resource theory. Bus. Manag. J. 2020, 9, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhong, W.; Xiong, Q. Analysis of indirect network externalities and competitive strategies on B2B platforms. J. Sys. Eng. 2014, 4, 550–559. [Google Scholar]

- Bogusz, C.I.; Teigland, R.; Vaast, E. Designed entrepreneurial legitimacy: The case of a Swedish crowdfunding platform. Euro. J. Infor. Sys. 2019, 28, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A. Digital platforms’ boundaries: The interplay of firm scope, platform sides, and digital interfaces. Long Range Plan. 2020, 54, 102045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, Q. Institutional entrepreneurship and legitimacy acquisition of new platform enterprises under the network environment: A case study of Xiaomi Company. R&D Manag. 2019, 31, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J. Legitimacy building and e-Commerce platform development in China: The experience of Alibaba. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 139, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, N.; He, J.; Wang, J. Institutional pressure and entrepreneurial strategic selections of firms facing Internet plus—A case study based on Didi Chuxing platform. China Indus. Econ. 2017, 3, 174–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Yan, Z.; Mei, L.; Chen, J. The Evolution of Platform Enterprises Based on Data Resources: Lessons from Variflight Company. Bus. Manag. J. 2020, 6, 96–115. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, K. Open Platform strategies and innovation: Granting access vs. devolving control. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 1849–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cai, N.; Sheng, Y. Cross-border entrepreneurship of focal enterprises—Dual platform architecture and industrial cluster ecosystem upgrading—A case study of Jiangsu Yixing environment hospital. China Indus. Econ. 2018, 2, 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Cusumano, M.A.; Gawer, A. The elements of platform leadership. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2003, 31, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H. Digital platform-based ecosystem view: A new perspective on management theory in the era of digital economy. China Indus. Econ. 2023, 40, 122–141. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, G.; Alstyne, M.V. Innovation, openness, and platform control. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce (EC-2010), Cambridge, MA, USA, 7–11 June 2010; Volume 6, pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. The Logic of open innovation: Managing intellectual property. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auracher, A. Getting Platform envelopment right to emerge as the ecosystem platform leader—A case study on Facebook and LinkedIn. In Proceedings of the 7th IBA Bachelor Thesis Conference, Enschede, The Netherlands, 1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkilä, L.I. Taxonomy of platform envelopment: A case-study of Apple and Samsung. In Proceedings of the 5th IBA Bachelor Thesis Conference, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mohagheghzadeh, A.; Svahn, F. Transforming organizational resource into platform boundary resource. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Istanbul, Türkiye, 12–15 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- West, J. How open is open enough? Melding proprietary and open source platform strategies. Res. Policy 2003, 32, 1259–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, K.J. Platform boundary choices & governance: Opening-up while still coordinating and orchestrating. In Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Platforms; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017; Volume 37, pp. 227–297. [Google Scholar]

- Gawer, A. Platforms Markets & Innovation, 1st ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 45–76. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Ning, P. Platform boundary selection and platform ecological governance. Chin. Soc. Sci. Abs. 2021, 5, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, T.R.; Parker, G.; Alstyne, M.V. Opening Platforms: How, When and Why? In Platforms, Markets and Innovation, 1st ed.; Gawer, A., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2008; pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony, S.; Karp, R. From proprietary to collective governance: How do platform participation strategies evolve? Strat. Manag. J. 2022, 43, 530–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.; Wright, J. Two-sided markets, competitive bottlenecks and exclusive contracts. Econ. Theory 2007, 32, 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunca, B.; Sharapov, D.; Tee, R. Governance rigidity, industry evolution, and value capture in platform ecosystems. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhu, K.; Gustafsson, R.; Lyytinen, K. Exploiting and defending open digital platforms with boundary resources: Android’s five platform forks. Inf. Syst. Res. 2018, 29, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethiraj, S.K.; Zhou, Y.; Chung, H. Platform governance in the presence of within-complementor interdependencies: Evidence from the rideshare industry. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Pereira, J.I.; Patel, P.C. Decentralized governance of digital platforms. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1305–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatmand, F.; Lindgren, R.; Schultze, U. Configurations of platform organizations: Implications for complementor engagement. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenamor, J.; Frishammar, J. Openness in platform ecosystems: Innovation strategies for complementary products. Res. Policy 2021, 50, 104148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, N.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Qu, Q. Process mechanism of platform-based ecosystem strategic renewal: An interdependence building perspective. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2023. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/12.1288.f.20230308.0928.002.html (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Adner, R. Ecosystem as structure: An actionable construct for strategy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, F. Information transparency, multihoming, and platform competition: A natural experiment in the daily deals market. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenamor, J. Complementor competitive advantage: A framework for strategic decisions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreieck, M.; Wiesche, M.; Krcmar, H. From product platform ecosystem to innovation platform ecosystem: An institutional perspective on the governance of ecosystem transformations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2022, 23, 1354–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isckia, T.; Reuver, M.D.; Lescop, D. Orchestrating platform ecosystems: The interplay of innovation and business development subsystems. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2020, 32, 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Sun, D.; Shan, Y.; Wang, C. The co-evolution of digital platform’s internationalization and ecosystem-specific advantages: The case of TikTok. Econ. Manag. 2023, 11, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, K.; Kenney, M.; Mattila, J.; Seppälä, T. The application of artificial intelligence at Chinese digital platform giants: Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent. ETLA Rep. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pan, C.; Zhao, S. Research on the process mechanism of the formation of digital platform ecosystem—Based on Haier’s exploratory case analysis. J. Manag. 2024, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobides, M.G.; Winter, S.G. Capabilities: Structure, agency, and evolution. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 1365–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, D.; Lu, R. Multilateral relationships faced by complementors in the platform ecosystem: Theoretical tracing and framework construction. R&D Manag. 2023, 35, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, W.; Jiang, S.; Liu, S. Strategies for complementors in platform ecosystem: The decoupling of complementarity and dependence. Manag. World 2021, 2, 126–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Wang, J. Platform-dependent upgrade: Digital transformation strategy of complementors in platform-based ecosystem. Manag. World 2021, 10, 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, H.; Zhang, R.; Yang, J. Corporate strategic choices and digital platform-based ecosystem building in the context of the digital economy: A Case Study from the Coevolution Perspective. Manag. World 2023, 12, 201–229. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.; Ceccagnoli, M.; Forman, C.; Wu, D.J. When do ISVs join a platform ecosystem? evidence from the enterprise software industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 15–18 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W. How platform enterprises can stimulate innovation among ecological complementors. Tsinghua Manag. Rev. 2021, 5, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- He, J. Competitive strategies for innovation platforms: Frontier progress and expansion direction. Econ. Manag. 2020, 42, 190–208. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, H.; Ma, G.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. A study on the dynamic governance mechanism of digital platform ecosystem: From the perspective of the interaction and influence between platform owners and complementors. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. Soc. Sci. 2024, 44, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Cao, J.; Liu, Z.; Luo, X. Sustainable business model based on digital ttwin platform network: The inspiration from Haier’s case study in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellemans, I.; Porter, A.J.; Diriker, D. Harnessing digitalization for sustainable development: Understanding how interaction on sustainability-oriented digital platforms manage tensions and paradoxes. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, O.; Ritala, P.; Keranen, J. Digital platforms for the circular economy: Exploring meta-organizational orchestration mechanisms. Organ. Environ. 2023, 36, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, C.; Parida, V.; Dhir, A. Linking circular economy and digitalization technologies: A systematic literature review of past achievements and future promises. Technol. Forecast. 2022, 177, 121508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damioli, G.; Van Roy, V.; Vertesy, D. The impact of artificial intelligence on labor productivity. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2021, 11, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, H.; Naskali, J.; Kimppa, K. Hub companies shaping the future: The ethicality and corporate social responsibility of platform economy giants. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGSOFT International Workshop on Software-Intensive Business: Start-ups, Platforms, and Ecosystems, Tallinn, Estonia, 26 August 2019; IWSiB 2019. Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Nie, X.; Lin, G. Protection of young people’s online rights and Interests: Platform responsibility and co-governance. Media Obs. 2018, 11, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yin, J.; Xi, M. Service pattern modeling and simulation: A case study of rural Taobao. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Services Computing (SCC), Beijing, China, 18–24 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, H.; Xie, H.; Chen, X. Sustainable Development of Platform Enterprises: A Synthesis Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114677

Zhou H, Xie H, Chen X. Sustainable Development of Platform Enterprises: A Synthesis Framework. Sustainability. 2024; 16(11):4677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114677

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Huanhuai, Hongming Xie, and Xiaoping Chen. 2024. "Sustainable Development of Platform Enterprises: A Synthesis Framework" Sustainability 16, no. 11: 4677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114677

APA StyleZhou, H., Xie, H., & Chen, X. (2024). Sustainable Development of Platform Enterprises: A Synthesis Framework. Sustainability, 16(11), 4677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114677