Abstract

In response to the escalating significance of sustainable tourism and the growing global concern for environmental conservation, the current study sought to investigate the intricate dynamics of two pro-environmental behaviors (biodiversity protection and rational car use), personal values (altruistic, biospheric, and egoistic), farm tourists’ well-being, and environmental and activity attachment among farm tourists in the Al-Ahsa region of Saudi Arabia. Employing an online survey, our methodology involved partial least structural equation modeling to unravel the complex relationships among these variables. Based on responses retrieved from 309 farm tourists, results revealed that biodiversity protection significantly influenced altruistic values and the well-being of farm tourists. Additionally, rational automobile use exerted positive impacts on both altruistic and biospheric values. These results underscore the intricate dynamics shaping tourists’ attitudes and experiences in the Al-Ahsa region. The study contributes to the broader understanding of sustainable tourism practices, emphasizing the need for tailored interventions. The positive associations identified highlight the potential for farm tourism experiences to enhance both pro-environmental values and the well-being of tourists, thus offering valuable insights for future research and sustainable tourism initiatives.

1. Introduction

Al-Ahsa is a region in Saudi Arabia that is famous for its farm tourism. Al-Ahsa is home to the Al-Ahsa Oasis, the largest oasis in the world, which covers an area of 2500 square kilometers (965 square miles) and has over 3 million palm trees [1]. The oasis is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as it represents traces of human settlement in the Gulf region from the Neolithic to the present [2]. Al-Ahsa has a rich cultural heritage and a diverse natural landscape, with gardens, canals, springs, wells, mountains, caves, villages, mosques, and archaeological sites [2]. As with other agricultural regions, farm tourism in Al-Ahsa is a form of tourism that involves visiting rural areas and engaging in agricultural activities, such as harvesting crops, raising animals, or learning about local farming practices. Farm tourism can offer a unique and authentic experience of the countryside, as well as an opportunity to support the local economy and environment.

Actually, promoting pro-environmental behavior in farm tourism is crucial for both global and local sustainability. Sustainable practices are necessary to preserve natural resources and biodiversity [3]. Biodiversity protection and rational automobile use are two key pro-environmental behavior subscales that can contribute to sustainable and responsible tourism practices. Biodiversity protection refers to the actions and attitudes of tourists that aim to minimize the negative impacts of tourism on the natural environment and its diversity of life forms. Biodiversity protection can contribute to sustainable tourism by enhancing the attractiveness and quality of destinations [4,5]. Rational automobile use refers to the decision-making process of tourists regarding the mode of transport they choose for their trips, taking into account the environmental, social, and economic factors. Rational automobile use can contribute to sustainable tourism by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, noise pollution, energy consumption, and waste generation from transport activities [6]. Actually, sustainable tourism encompasses a broad range of practices aimed at minimizing environmental impact while enhancing the well-being of tourists. Biodiversity protection is a cornerstone of sustainable tourism, ensuring the preservation of natural habitats and species. However, sustainable transportation, particularly rational automobile use, is equally important in reducing carbon emissions and mitigating climate change. Integrating these two variables allows us to explore a more holistic view of sustainable tourism practices. While biodiversity protection addresses the conservation of natural resources, rational automobile use tackles the reduction in transportation-related environmental impacts. Together, these practices contribute to a comprehensive understanding of how various pro-environmental behaviors can enhance the sustainability of tourism destinations.

The domains of pro-environmental behavior can influence personal values of tourists. These values are beliefs and principles that guide individuals’ behavior and decision-making. Research has shown that engaging in pro-environmental behaviors can lead to a shift in personal values, fostering a greater sense of responsibility towards the environment. For instance, tourists who participate in eco-friendly activities, such as wildlife conservation programs or sustainable farming practices, often develop stronger biospheric and altruistic values over time [7,8]. These experiences can heighten their awareness of environmental issues and reinforce the importance of preserving nature for future generations. Additionally, the adoption of sustainable practices, such as recycling, energy conservation, and reduced automobile use, has been linked to increased environmental awareness and shifts in personal values among individuals [9,10]. These behaviors are often driven by an underlying set of values that prioritize environmental stewardship and altruism. As individuals engage more deeply with these practices, they may find their values becoming more aligned with the principles of sustainability and environmental ethics. For example, a study by Steg, Bolderdijk, Keizer, and Perlaviciute [11] found that promoting energy-saving behaviors in households not only reduced energy consumption but also led to a significant increase in biospheric values among participants. Similarly, participating in community-based environmental projects has been shown to enhance individuals’ commitment to pro-environmental values and behaviors [12].

These findings suggest that pro-environmental behaviors do not merely reflect existing personal values but can actively shape and reinforce them. In the current study, we considered three main subscales of personal values: altruistic value, biosphere value, and egoistic value. Altruistic value refers to the importance of helping others and contributing to society, whereas biosphere value reflects the importance of preserving the environment and protecting nature. Egoistic value refers to the importance of personal achievement and success [13]. Personal values can in turn affect individuals’ well-being, decision-making, and behavior in tourism destinations [14,15].

Moreover, the exploration of tourists’ well-being in relation to their attachment to destinations has been a focal point of scholarly search. Within the realm of farm tourism, this attachment assumes significance in fostering sustainable practices and responsible tourism [16]. Notably, research indicates that the four dimensions of attachment theory positively and significantly influence both pro-environmental behavior and well-being [17]. In the current study, we included two dimensions of the attachment theory, namely environmental attachment and activity attachment. Environmental attachment refers to the emotional connection individuals feel towards natural environments, which can influence their behavior and attitudes towards environmental conservation [16]. Activity attachment can be interpreted as the level of engagement and connection tourists have with the activities and experiences offered by farms during their visit. While these activities often take place on the farm, such as picking fresh produce or interacting with farm animals, they can also include related activities carried out outside the farm that contribute to the overall farm tourism experience. The well-being of tourists can have a significant impact on their activity attachment, affecting their overall satisfaction and likelihood to return to the farm [17,18].

However, the existing literature on sustainable tourism, particularly in the context of farm tourism in the Al-Ahsa region, reveals a noticeable research gap. While various studies have explored the broader relationship between pro-environmental behavior and well-being among tourists [17,19,20], there is a lack of in-depth investigations that specifically delve into the distinct pro-environmental behavior subscales of biodiversity protection and rational automobile use. Additionally, personal values, encompassing altruistic, biosphere, and egoistic values, remain underexplored within the farm tourism framework in Al-Ahsa. This research gap underscores the need for a comprehensive study that examines the intricate connections between these pro-environmental behaviors, personal values, and the resultant impact on the well-being of farm tourists in this unique cultural and ecological setting. The impact of well-being on tourists’ attachment should also be acknowledged. The primary objectives of the current study are to explore the relationships between two major subdomains of pro-environmental behaviors (biodiversity protection and rational automobile use) and three subscales of personal values (altruistic value, biosphere value, and egoistic value) and to assess their collective impact on the well-being of farm tourists. Furthermore, we aimed to explore the influence of tourists’ well-being on environmental and activity attachment.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Biodiversity Protection and Farm Tourists’ Values

The importance of biodiversity protection in agricultural sustainability is crucial for maintaining the health and balance of ecosystems, which in turn contribute to the sustainability of agricultural practices. Biodiversity protection can significantly impact the altruistic values of farm tourists. Studies have indicated that the endorsement of habitat restoration and biodiversity protection is commonly rooted in ecocentric values and attitudes [21,22]. For instance, research conducted in China revealed that tourists with conservation backgrounds tended to allocate greater funds toward general non-use values, while high-income tourists demonstrated a willingness to pay more for the altruistic value associated with ecotourism resources [23]. Furthermore, the management and preservation of biodiversity on farms offer extensive opportunities to cultivate nature-rich pastoral landscapes, underscoring the significance of understanding farmers’ perspectives on the value of native biodiversity on their lands as a pivotal step toward instigating requisite behavioral changes [24]. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1a.

Biodiversity protection significantly impacts the altruistic values of farm tourists.

Biodiversity protection can also influence biospheric values by allowing tourists to observe and appreciate diverse habitats and ecosystems, raising awareness about habitat conservation and promoting a deeper understanding of the local environment [25]. Studies have shown that environmentally friendly farming practices, which enhance the beauty and diversity of flora and fauna, can attract farm tourists and contribute to the overall appeal of the farm as a tourist destination [26]. For example, tourists who visit farms that practice biodiversity conservation are more likely to develop an appreciation for the ecological benefits of such practices, which in turn can reinforce their biospheric values [10]. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1b.

Biodiversity protection significantly impacts the biospheric values of farm tourists.

Regarding egoistic values, research indicates that individuals’ recreational pursuits and value perceptions of pleasant sites are correlated with comprehensive biodiversity and cultural heritage values [27]. A study in Indonesia emphasized the potential of ecotourism and agrotourism grounded in plant variety preservation to bolster biodiversity conservation and sustainable economic growth, showing that tourists who engage in these activities often develop a stronger personal connection to the environment [26]. Additionally, experiences in biodiversity-rich environments can enhance tourists’ enjoyment and personal satisfaction, linking their egoistic values to the preservation of biodiversity [13]. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1c.

Biodiversity protection significantly impacts the egoistic values of farm tourists.

In general, the attachment theory and value–belief–norm (VBN) theory further explain how tourists’ emotional bonds with biodiverse environments and their value–belief–norm pathways influence their pro-environmental behaviors. Attachment theory posits that individuals form emotional bonds with places, which can lead to strong place attachment and influence behaviors to protect and preserve these places [28]. Tourists who develop an attachment to biodiverse environments are more likely to value and engage in conservation efforts. Meanwhile, VBN theory suggests that values influence beliefs, which in turn form norms that guide behavior [8]. Tourists with strong biospheric and altruistic values are likely to believe in the importance of biodiversity, creating personal norms that drive pro-environmental behaviors. These theoretical perspectives provide a robust framework for understanding how biodiversity protection impacts the values and behaviors of farm tourists.

2.2. Rational Automobile Use and Farm Tourists’ Values

Rational automobile use may play a role in shaping the values of tourists. Such a concept, as defined in the current study, involves making environmentally conscious transportation choices such as using eco-friendly vehicles, carpooling, and reducing car usage to minimize environmental impact. Rational automobile use is supported by the existing body of literature, which highlights the importance of sustainable transportation in reducing the negative environmental impacts associated with tourism [29,30]. For instance, Fjelstul and Fyall [6] emphasize the role of sustainable drive tourism in promoting environmental awareness among tourists. Additionally, Werdiyasa [31] discusses the potential of electric vehicles in transforming Bali into an eco-tourism destination. These studies provide a foundation for understanding how rational automobile use can influence tourists’ values and behaviors in a farm tourism context.

The ability to use a personal vehicle allows tourists to explore rural landscapes at their own pace, fostering a sense of freedom and independence. This autonomy enhances their appreciation for the natural environment, as they can stop and admire scenic views whenever they wish. Moreover, car use enables tourists to access remote farm locations that may not be served by public transportation. This accessibility increases their exposure to authentic rural experiences, such as picking fresh produce or interacting with farm animals, which can deepen their understanding and respect for agricultural practices and rural lifestyles [32,33]. However, it is important to note that while car use can enhance the tourist experience, it also has potential downsides. Excessive car use can lead to traffic congestion and environmental degradation, negatively impacting the rural tranquility and natural beauty that attract tourists in the first place [34,35]. Therefore, it is crucial for tourists to balance their desire for exploration and convenience with the need to preserve the environments they visit.

Rational automobile use can significantly impact the altruistic values of farm tourists. The relationship between sustainable transportation choices and altruistic values is influenced by factors such as carbon emissions, traffic congestion, and the preservation of rural landscapes. Tourists with strong altruistic values are likely to engage in environmentally responsible behavior, including rational automobile use, to minimize their environmental impact [7,36]. Additionally, research focusing on rational planning strategies to mitigate transport carbon dioxide emissions in developing cities highlights the importance of reducing car usage as a key strategy, which aligns with the pro-environmental behavior associated with altruistic values [37]. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H2a.

Rational automobile use significantly impacts the altruistic values of farm tourists.

Rational automobile use can also influence the biospheric values of farm tourists. Sustainable transportation choices, such as using eco-friendly vehicles and carpooling, can reduce the negative environmental impacts associated with tourism, such as greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution [29,30]. This reduction in environmental impact can enhance tourists’ environmental awareness and commitment to sustainable practices, reinforcing their biospheric values [31,35]. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H2b.

Rational automobile use significantly impacts the biospheric values of farm tourists.

Regarding egoistic values, rational automobile use can enhance tourists’ personal well-being and satisfaction by providing a more enjoyable and responsible travel experience. Tourists with strong egoistic values may prioritize sustainable transportation options that reduce their environmental impact and contribute to their personal satisfaction and enjoyment [13,32]. Studies have shown that individuals’ recreational pursuits and value perceptions of pleasant sites are correlated with comprehensive biodiversity and cultural heritage values, suggesting that rational automobile use can positively impact tourists’ egoistic values [27]. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H2c.

Rational automobile use significantly impacts the egoistic values of farm tourists.

From the theoretical point of view, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Self-Determination Theory (SDT) provide a comprehensive explanation of how tourists’ attitudes, social norms, perceived behavioral control, and motivation for autonomy influence their transportation choices and values. TPB suggests that behavior is driven by behavioral intentions, which are influenced by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [38]. Tourists’ positive attitudes towards rational automobile use, social norms supporting sustainable transportation, and their perceived ability to use eco-friendly vehicles shape their transportation choices and values. SDT focuses on motivation and autonomy, emphasizing that individuals are motivated to engage in behaviors that fulfill their needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness [39]. Rational automobile use can enhance tourists’ sense of autonomy and competence in making environmentally conscious choices, which in turn can influence their values and behaviors. These theoretical perspectives provide a robust framework for understanding how rational automobile use impacts the values and behaviors of farm tourists.

2.3. The Impact of Farm Tourists’ Values and Behavior on Their Well-Being

Biodiversity protection and rational car use are two key factors that can enhance the well-being of tourists who visit farm destinations by promoting a healthier and more sustainable environment. However, it is important to recognize that limiting car use might affect mobility and convenience, which could negatively impact some aspects of tourists’ well-being. By conserving biodiversity and reducing car use for sustainable tourism development, tourists can enjoy a more meaningful and responsible travel experience, while also contributing to the conservation, restoration, and enhancement of natural resources, as well as improving the quality, equity, and resilience of rural communities. The negative impacts of uncontrolled tourism, including car use, can lead to adverse environmental effects such as habitat loss and pollution [40]. By promoting alternative modes of transportation and reducing car use, farm tourists can experience a more peaceful and environmentally friendly setting, which can enhance their overall well-being during their visit. Moreover, ecotourism is considered the best approach for the joint promotion of biodiversity protection and sustainable tourism development [41]. This indicates that activities that support biodiversity protection, such as ecotourism, can enhance the tourism experience for farm tourists by allowing them to engage with and appreciate diverse natural environments.

From another perspective, the impact of personal values on the well-being of farm tourists can be significant. Personal values, including altruistic, biosphere, and egoistic values, may be linked to subjective well-being and destination-loyalty intention in the context of tourism. Altruistic values, which reflect concern for the well-being of others, have been shown to be significant drivers of environmentally responsible behavior among tourists [42]. Tourists with a high level of altruistic values tend to engage in eco-friendly travel and view it as worthwhile [43]. This suggests that farm tourists with strong altruistic values may experience greater well-being due to their environmentally responsible behaviors and the positive impact of such activities on the environment. Furthermore, research indicates that tourists’ biosphere values and attitudes are important mediators of environmentally responsible attitudes [43]. This implies that farm tourists who hold biosphere values in high regard may be more inclined to engage in environmentally friendly activities during their visits, leading to a positive impact on their well-being. Importantly, although it may seem obvious that a strong connection to nature positively influences well-being, it is important to empirically validate this relationship within the specific context of farm tourism. Understanding the extent and nature of this impact can help develop targeted interventions and policies that enhance the well-being of tourists by promoting biospheric values. Egoistic values, which focus on self-enhancement and personal well-being, can also influence the well-being of tourists. While the impact of egoistic values on well-being in the specific context of farm tourism may not be directly addressed in the literature, it can be inferred that tourists with strong egoistic values may prioritize activities that enhance their personal well-being during their farm visits [43]. As a consequence, we assume the following:

H3.

Biodiversity protection significantly impacts the well-being of farm tourists.

H4.

Rational automobile use significantly impacts the well-being of farm tourists.

H5.

Altruistic value significantly impacts the well-being of farm tourists.

H6.

Biosphere value significantly impacts the well-being of farm tourists.

H7.

Egoistic value significantly impacts the well-being of farm tourists.

2.4. The Impact of Farm Tourists’ Well-Being on Environmental and Activity Attachment

The well-being of tourists holds considerable sway over their environmental and activity attachment, especially within the realm of farm tourism. Research indicates that heightened attachment to a place correlates with a greater inclination to protect it [44]. This suggests that tourists who experience higher well-being during their farm visits are more likely to develop a strong attachment to the environment and activities associated with the farm. Well-being, in this context, encompasses overall happiness, life satisfaction, and physical and mental health, which can be significantly enhanced through positive and meaningful experiences on the farm [45].

Well-being significantly impacts environmental attachment. When tourists have positive experiences and feel content and satisfied with their visits, they are more likely to form a deep emotional connection to the environment. This connection motivates them to engage in behaviors that protect and preserve the natural settings they have grown attached to. Studies have shown that well-being is linked to increased environmental awareness and pro-environmental behaviors, suggesting that the more tourists feel at ease and happy in a natural setting, the more likely they are to develop a protective stance towards it [28,46]. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H8.

The well-being of farm tourists significantly impacts environmental attachment.

Well-being also impacts activity attachment. Tourists who enjoy high levels of well-being are more likely to engage deeply in activities that enhance their travel experience. These activities might include picking fresh produce, interacting with farm animals, or participating in traditional farming practices. The satisfaction and joy derived from these activities can lead to a stronger attachment to the activities themselves, encouraging repeat visits and sustained engagement [47,48]. Positive well-being thus reinforces tourists’ desire to engage in farm-related activities, creating a cycle of attachment that benefits both the tourists and the farm operators. In the current study, we considered the attachment of farm tourists towards various activities offered at the farm, such as picking fresh produce, interacting with farm animals, participating in farm tours, and engaging in traditional farming practices. By enhancing tourists’ well-being, these activities can foster a stronger emotional connection, leading to increased activity attachment. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H9.

The well-being of farm tourists significantly impacts activity attachment.

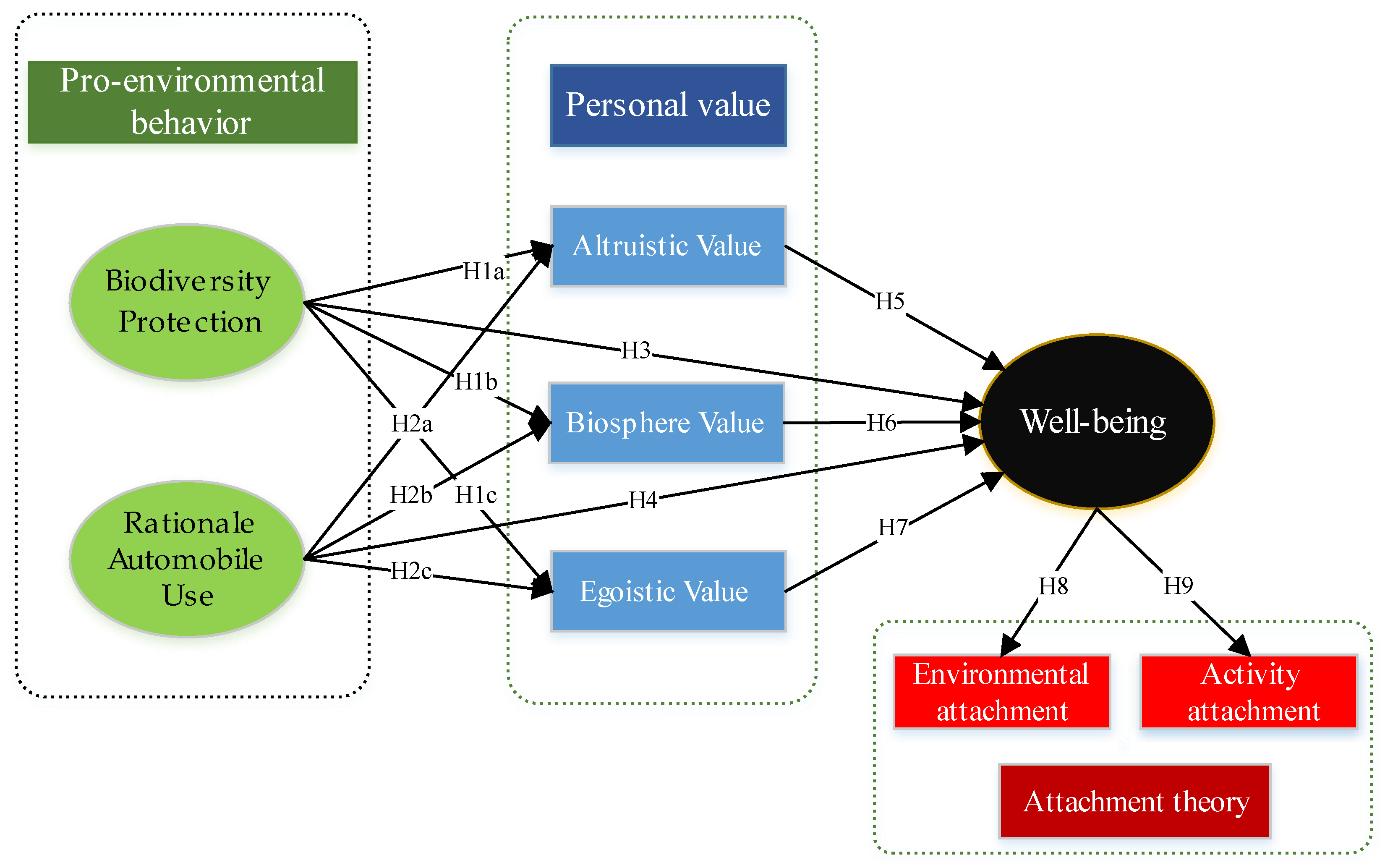

Below, we summarize the hypothesized framework in a visual flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The hypotheses and relationships of the current study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Construct Measures

The questionnaire utilized in this study comprises several scales and subscales designed to assess farm tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors, personal values, attachment to the environment, and well-being. The pro-environmental behavior scale encompasses biodiversity protection and rational automobile use. Biodiversity protection refers to the actions and attitudes of tourists aimed at minimizing the negative impacts of tourism on the natural environment and its diversity of life forms. This variable includes behaviors such as leaving outdoor sites clean; collecting plants, seeds, and organic matter; and visiting national parks or nature reserves; these items were retrieved from previous research [49]. These actions reflect tourists’ active participation in conserving biodiversity during their farm visits. Engaging in such activities can enhance tourists’ awareness and appreciation of biodiversity, fostering a deeper connection with nature and encouraging sustainable tourism practices [4,5]. Rational automobile use refers to the environmentally conscious decision-making process regarding transportation choices by tourists. This includes preferences for walking or biking short distances, car-sharing habits, refraining from driving on high-pollution days, and minimizing the use of car horns. These behaviors reflect tourists’ efforts to reduce their environmental impact through mindful transportation choices [29,30]. The items of the rational automobile use were adapted from a published article by Bronfman et al. [49].

Personal values are measured through three subscales [49]: biospheric values (e.g., beliefs in environmental stewardship and harmony with other beings), altruistic values (e.g., importance of helping others and fair treatment of all people), and egoistic values (e.g., decision-making and financial importance). The attachment theory scale assesses environmental attachment through items capturing increased recognition of environmental protection due to farm tourism experiences [17]. The activity attachment subscale gauges participants’ affinity for farm tourism activities and their impact on nature appreciation. Finally, well-being is a holistic measure of tourists’ overall happiness, life satisfaction, physical and mental health, and optimism about the future. This variable includes items assessing happiness, proximity to the ideal life, life satisfaction, interest in daily activities, optimism about the future, and physical and mental health. These measures capture the subjective well-being and quality of life of the tourists [17]. A full list of items and domains is presented in Appendix A.

3.2. Data Collection

Tourist data were acquired from individuals visiting farms in Saudi Arabia through the dissemination of an online questionnaire containing the aforementioned scales. A total of 309 fully completed responses were gathered, and to ensure the representation of farm tourists, respondents had to meet specific criteria. Participants were required to be over 18 years old to obtain viewpoints from fully independent individuals. Additionally, they needed to have visited a farm tourism destination within the past year to ensure relatively fresh and relevant memories. The primary motivation for the visit had to be leisure or recreation rather than work, excluding those on business trips. Moreover, participants were obligated to have directly experienced farm activities and products instead of merely viewing the farm setting. These criteria were deliberately chosen to filter the sample and include individuals who had authentic engagements with farm contexts, strengthening the study’s validity and its ability to draw meaningful conclusions.

To attain this targeted sample, collaboration was established with a tourism firm specializing in farm tourism operations across Saudi Arabia. The firm facilitated the distribution of the questionnaire link to its past customers through email lists and social media channels. This strategy ensured access to a pool of relevant participants who had engaged in farm visits facilitated by the firm. The online data collection method allowed for flexibility for the respondents in terms of time and location, resulting in a sizable sample gathered within a relatively short 4-week period from 23 November to 21 December 2023 to meet the target response rate. The survey administration underwent rigorous monitoring, with daily reviews of response tallies, follow-up messages through the partner firm’s communication platforms to encourage further participation, and regular checks to ensure selection criteria adherence. This meticulous process yielded a high-quality dataset of 309 valid responses, representing a diverse sample of Saudi farm tourists and enhancing the analytical capabilities and statistical power of the study. The sample was characterized by a predominant representation of females (74.8%) and individuals aged between 18 and 24 years (60.8%). Additionally, a substantial proportion, accounting for nearly three-quarters of the tourists (75.8%), reported a tendency to travel in the company of a friend. Furthermore, a noteworthy percentage, totaling 66.0% of the respondents, indicated frequent visits to Al-Ahsa, with three or more instances of visitation.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The analysis of the data was conducted using RStudio (R version 4.3.1). Categorical data were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Constructs were modeled using bootstrapped partial least squares structural equation modeling. Internal consistency reliability was assessed through the computation of Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. To evaluate the assumption of equal indicator loadings inherent in Cronbach’s alpha, rhoC values were calculated as an indicator of composite reliability, following Jöreskog’s approach [50]. Additionally, the more conservative measure of internal consistency, rhoA, was utilized based on the recommendation of Dijkstra and Henseler [51]. Convergent validity was assessed by employing the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) to determine the extent to which each domain collectively explains the observed variances in the indicators [52]. Following the guidelines provided by Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt [53], discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the square roots of the AVE with the correlations between different constructs and utilizing the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) of correlations. The bootstrapped structural model was implemented using a 1000-bootstrap method, following the procedure outlined by Streukens and Leroi-Werelds [54]. Results were presented in terms of beta coefficients, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), with statistical significance indicated by a p-value of 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Convergent Validity and Construct Reliability

Within the framework of the bootstrapped model, the analysis unveiled that two items displayed statistically insignificant loadings with respect to their corresponding constructs. These items included one within the activity attachment subscale and another within the well-being subscale. Further details regarding the inclusion and exclusion of items can be found in Appendix A. The results presented in Table 1 demonstrate that the final bootstrapped model exhibited commendable levels of reliability. The mean bootstrap factor loadings for the items attained statistical significance, surpassing the threshold of 0.50. Additionally, both the rhoC and rhoA values were higher than 0.70, as per established criteria [50,51]. Remarkably, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.832 to 0.929, denoting robust internal consistency across the constructs. AVE values ranged from 0.531 to 0.909, suggesting that each respective domain accounted for no less than 53.1% of the observed variance in the indicators comprising that specific domain [52] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Convergent validity and construct reliability.

4.2. Discriminant Validity

In assessing discriminant validity, an analysis involved comparing the square roots of the AVE with the shared variance among different constructs, as indicated by inter-domain correlations. As delineated in Table 2, a consistent finding emerged: the square roots of the AVE consistently exceeded the correlations across different domains. Furthermore, the findings presented in Table 3, which encompassed bootstrapped HTMT values and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), consistently remained below the established threshold of 1.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Results of the bootstrapped HTMT.

4.3. Structural Model

The path analysis revealed statistically significant associations in several key relationships. Biodiversity protection demonstrated a positive and significant impact on altruistic values (beta = 0.223, 95% CI: 0.059 to 0.410, p = 0.006), supporting H1a. However, biodiversity protection was found to have no significant effect on biospheric values (beta = −0.064, 95% CI: −0.140 to 0.011, p = 0.950) and egoistic values (beta = 0.159, 95% CI: −0.032 to 0.351, p = 0.055). Rational automobile use exhibited a positive and significant impact on altruistic values (beta = 0.688, 95% CI: 0.510 to 0.850, p < 0.0001) and biospheric values (beta = 0.921, 95% CI: 0.840 to 0.998, p < 0.0001), supporting H2a and H2b, respectively. However, rational automobile use did not significantly affect egoistic values (beta = 0.090, 95% CI: −0.101 to 0.278, p = 0.180), rejecting H2c. Biodiversity protection positively influenced well-being (beta = 0.164, 95% CI: 0.041 to 0.344, p = 0.048), supporting H3. In contrast, rational automobile use did not significantly impact well-being (beta = 0.275, 95% CI: −0.091 to 0.623, p = 0.070), rejecting H4. Notably, the three personal value subscales did not affect tourists’ well-being. Additionally, well-being in turn did not influence environment and activity attachment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of the structural model.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion of the Study Findings

In the current study, we obtained insights into the interplay of pro-environmental behaviors, personal values, well-being, and attachment among farm tourists in the Al-Ahsa region. Our study aimed to explore the intricate relationships within this integrative model. Through a path analysis, we sought to unravel the underlying dynamics shaping tourists’ attitudes and experiences. The key findings unveiled significant associations that contribute to our understanding of sustainable tourism practices. Biodiversity protection emerged as a potent predictor of altruistic values. Moreover, rational automobile use exhibited a positive impact on both altruistic and biospheric values. However, it did not significantly influence egoistic values, indicating a differential impact of sustainable transportation practices on personal values. These results provide valuable insights into the complex interrelationships at the nexus of environmental behaviors and personal values within the farm tourism context in Al-Ahsa.

In the present analysis, our identification of a significant impact of biodiversity protection on altruistic values among tourists raises intriguing questions about the underlying mechanisms driving this relationship. One plausible explanation lies in the transformative nature of engaging in biodiversity protection activities. Exposure to and active participation in such conservation efforts may evoke a heightened sense of connection to the natural environment, fostering a deepened appreciation for the intrinsic value of biodiversity. Additionally, the hands-on experience of contributing to biodiversity protection initiatives may stimulate a sense of responsibility and empathy towards other species, ultimately shaping altruistic values. Furthermore, the tangible outcomes of biodiversity protection efforts, such as witnessing the positive impact on local ecosystems or observing the flourishing of specific species, can serve as powerful catalysts for altruistic sentiments. Importantly, these experiences may act as a conduit for tourists to recognize the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the role of altruistic values in sustaining ecological balance. The findings resonate with the broader literature emphasizing the role of experiential learning in shaping environmental attitudes, suggesting that direct engagement with biodiversity protection initiatives during farm tourism plays a pivotal role in nurturing altruistic values among tourists. This aligns with the proposition that fostering altruistic values is not only conducive to sustainable tourism practices but also instrumental in promoting a broader commitment to pro-environmental behavior, echoing the interconnected dimensions of species concern, environmental willingness, environmental involvement, and destination loyalty identified in previous studies [7]. As demonstrated by Kim et al.’s research in South Korea [7], our findings parallel the mediating role of altruistic values in the relationship between environmental knowledge and pro-environmental actions. This intricate interplay suggests that interventions aimed at enhancing biodiversity protection experiences during farm tourism may not only directly contribute to conservation efforts but also serve as catalysts for the cultivation of altruistic values, ultimately fostering a more sustainable and environmentally conscious tourism paradigm.

Our findings also showed positive impacts of biodiversity protection on tourists’ well-being. Engaging in biodiversity protection practices during farm tourism not only serves as a means of conserving the rich variety of life on Earth but also contributes significantly to tourists’ well-being through various mechanisms. Our results indicate that biodiversity protection positively influences altruistic values, enhancing tourists’ concern for the welfare of other species. This resonates with the notion that tourism experiences in natural sites rich in biodiversity can raise awareness, fostering a sense of wonder, curiosity, and respect for nature [55,56]. Furthermore, our findings are congruent with the idea that tourism serves as a platform for skills and education related to biodiversity conservation [4]. As tourists participate in conservation activities, such as identifying different species, observing behavior and habitats, and supporting local communities, they not only acquire new skills but also deepen their connection with biodiversity. Importantly, tourism also contributes to the conservation of biodiversity by generating income for projects that protect unique areas and species. This aligns with tourism revenue from gorilla tracking in Rwanda funding transboundary gorilla conservation agreements [57]. In essence, our study contributes to the broader understanding of the positive interplay between biodiversity protection, personal values, and well-being among farm tourists, highlighting the integral role of tourism in promoting conservation awareness, education, and sustainable practices.

The findings presented in our study underscored the positive impact of rational automobile use on both altruistic and biospheric values among farm tourists, shedding light on the multifaceted benefits derived from sustainable transportation practices. Rational automobile use is posited as a catalyst for the enhancement of altruistic values through its mitigation of adverse environmental impacts associated with conventional car usage. By reducing car emissions, traffic congestion, noise pollution, and energy consumption, rational automobile use not only contributes to personal well-being but also extends its positive effects to the broader community and living beings. This aligns with findings from previous studies, such as the discovery that individuals with stronger biospheric and altruistic values exhibit a greater inclination to reduce their car use [58]. Additionally, the observed positive influence of biospheric values on consumers’ purchase intention for green cars among Chinese millennials [59] resonates with the notion that rational automobile use can foster and reinforce biospheric values.

Furthermore, our results posit that rational automobile use contributes to the cultivation of biospheric values by encouraging the adoption of more sustainable and eco-friendly modes of transportation. These alternative modes, including walking, cycling, public transport, and electric vehicles, are instrumental in mitigating environmental impacts such as greenhouse gas emissions, natural resource conservation, biodiversity preservation, and improved air quality. The referenced studies on reduced street lighting levels [60] underscore the broader implications of biospheric values, where individuals who strongly endorse these values are more likely to find environmentally conscious initiatives acceptable. This aligns with our findings, indicating a positive influence of rational automobile use on both altruistic and biospheric values among farm tourists.

It is noteworthy that the outcomes obtained in the current study underscore the multifaceted nature of sustainable tourism, where both biodiversity protection and rational automobile use play crucial roles. While biodiversity protection directly enhances the ecological health of tourism destinations, rational automobile use reduces transportation-related environmental impacts. These complementary practices contribute to the overall sustainability of farm tourism, promoting a more comprehensive approach to environmental conservation and tourist well-being. Future research should continue to explore the interconnectedness of various pro-environmental behaviors to provide a deeper understanding of sustainable tourism practices.

5.2. Limitations

In the current study, we formulated eleven pathway hypotheses based on a comprehensive review of the literature. However, the empirical results, as shown in Table 4, indicate that only four out of the eleven hypothesized pathways were supported by the survey data. The discrepancy between the proposed hypotheses and the empirical findings can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the unique cultural, environmental, and socio-economic context of the Al-Ahsa region likely influenced tourists’ values and behaviors differently than anticipated based on the broader literature. The predominantly young and female sample also impacted the generalizability of the results, as demographic factors can shape environmental attitudes and behaviors. The contextual specificity of Al-Ahsa might have led to different perceptions and priorities among tourists regarding biodiversity protection and rational automobile use, contributing to the rejection of several hypotheses.

The limitations of the current study further clarify these discrepancies. The utilization of a survey-based methodology, particularly online surveys, may introduce selection bias, as individuals who opt to participate may systematically differ from those who do not. This could influence the representativeness of our sample and limit the external validity of our results. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of our study design imposes limitations on our capacity to establish causation and ascertain the directionality of observed relationships. Self-report measures are also susceptible to social desirability biases, potentially leading to overestimations of pro-environmental behaviors and values. Lastly, the contextual specificity of our study within the Al-Ahsa region may constrain the extrapolation of results to diverse cultural or geographical settings. Additionally, while our dataset comprises 309 valid responses, the predominance of women and the large share of young people limit the representativeness of our sample, affecting the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the study was conducted among visitors of only one, quite specific place in the Al-Ahsa region, which may further constrain the extrapolation of the results to other regions or types of farm tourism destinations.

These factors collectively explain why only four pathways were accepted while the others were rejected. The differences between hypothesized relationships and empirical findings highlight the importance of considering regional and demographic specifics when studying pro-environmental behaviors and values. Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights and serves as a foundation for future research. Future studies should consider longitudinal designs, diverse samples, mixed-method approaches, and deeper exploration of regional factors to better understand these relationships in different tourism contexts.

5.3. Conclusions and Future Implications

In conclusion, our study provides a nuanced examination of the relationships between pro-environmental behaviors, personal values, well-being, and attachment among farm tourists in the Al-Ahsa region. The findings reveal significant associations, such as the positive impact of biodiversity protection on altruistic values and tourists’ well-being, as well as the fostering of altruistic and biospheric values through rational automobile use. However, the non-significant influence of personal values on tourists’ well-being and the absence of a direct connection between well-being and environmental and activity attachment underscore the complexity of these dynamics. Our study contributes to the growing body of literature by elucidating the intricate interrelationships in a specific cultural and geographic context, offering implications for sustainable tourism practices. While recognizing limitations, including the reliance on self-report measures, our research lays a foundation for future investigations to explore these relationships in diverse settings. Ultimately, the study advances our understanding of the mechanisms influencing tourists’ attitudes and behaviors, emphasizing the need for tailored interventions that integrate pro-environmental values, sustainable practices, and well-being considerations in the evolving landscape of farm tourism.

The findings of our study carry significant implications for future research and the development of interventions in the realm of sustainable tourism. Future investigations could delve into the cultural and contextual variations that may influence the relationships identified in our study, allowing for a broader understanding of how pro-environmental behaviors, personal values, well-being, and attachment interact across diverse settings. Longitudinal studies offer the potential to elucidate temporal dynamics and discern potential causal relationships, offering a deeper understanding of how these constructs evolve over time. Moreover, considering the transformative potential of farm tourism experiences, future research could explore the design and implementation of targeted interventions aimed at enhancing biodiversity protection and sustainable transportation practices among tourists. Such interventions may involve educational programs, immersive experiences, and community engagement initiatives to foster pro-environmental values and behaviors. Additionally, policymakers and stakeholders in the tourism industry could leverage our findings to develop strategies that promote sustainable practices, conserve biodiversity, and enhance the overall well-being of tourists. Ultimately, the future implications of our study extend beyond academic discourse, offering practical insights that can shape the trajectory of sustainable tourism initiatives and contribute to a more harmonious relationship between tourists and the environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.A. and T.H.H.; methodology, A.M.A. and T.H.H.; software, T.H.H. and A.M.A.; validation, M.A.A.; formal analysis, A.M.A. and M.A.A.; investigation, T.H.H. and M.A.A.; resources, T.H.H. and A.M.A.; data curation, T.H.H. and M.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.A. and M.A.A.; writing—review and editing, T.H.H. and M.A.A.; visualization, M.A.A. and A.M.A.; supervision, T.H.H.; project administration, A.M.A. and T.H.H.; funding acquisition, A.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia, for funding this research work through the project number INST212.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Deanship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study prior to participation on the online platform.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion if this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia, for funding this research project under grant number INST212.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Scales and subscales of the used questionnaire.

Table A1.

Scales and subscales of the used questionnaire.

| Scale | Subscales/Items | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental behavior | Biodiversity Protection | |

| Env_Bio_1 | After spending a day outdoors in farms, I leave the site as clean as it was when I got there | |

| Env_Bio_2 | I collect plants, seeds and organic matter when I visit farms | |

| Env_Bio_3 | I visit national parks and/or nature reserves | |

| Rational Automobile Use | ||

| Env_Car_1 | To travel short distances (less than 10 blocks), I prefer to walk or use a bike | |

| Env_Car_2 | I share a car | |

| Env_Car_3 | I refrain from driving a car on days of high pollution levels | |

| Env_Car_4 | I honk the horn when I drive | |

| Personal value | Biospheric Values | |

| Val_Bs_1 | A person who believes that everyone must look after the environment | |

| Val_Bs_2 | A person who respects the environment and believes that we should live in harmony with other living beings | |

| Altruistic Values | ||

| Val_Alt_1 | A person who believes it is important to help others around them | |

| Val_Alt_2 | A person who believes in the fair treatment of all people, including persons who are unknown to them | |

| Egoistic Values | ||

| Val_Ego_1 | A person who makes decisions and likes to be a leader | |

| Val_Ego_2 | A person who believes it is important to have a lot of money | |

| Attachment theory | Environment attachment | |

| Att_Env_1 | Because of my experience in farm tourism, I have increased my recognition of environmental protection | |

| Att_Env_2 | The experience of farm tourism makes me better understand the significance of environmental protection | |

| Att_Env_3 | For the sustainable development of the environment, I like to travel more to farms | |

| Activity attachment | ||

| Att_Act_1 | I like the farm tourism experience very much | |

| Att_Act_2 | Farm tourism experience activities bring me good memories | |

| Att_Act_3 | Farm tourism experience activities attract me more than other tourism experience activities | |

| Att_Act_4 | Farm tourism experience is very interesting for me | |

| Att_Act_5 * | The experience of farm tourism makes me love nature more | |

| Well-being | WB_1 * | I feel very happy |

| WB_2 | I am very close to my ideal life | |

| WB_3 | I am very satisfied with life | |

| WB_4 | I am interested in daily activities | |

| WB_5 | I am optimistic about the future | |

| WB_6 | I am physically and mentally healthy | |

| WB_7 | I think my living environment is very good |

*An asterisk indicates excluded items.

References

- Jaffery, R. Visit Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia’s UNESCO-Listed Oasis. Available online: https://theculturetrip.com/middle-east/saudi-arabia/articles/a-tour-of-al-ahsa-saudi-arabias-unesco-listed-oasis (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention Al-Ahsa Oasis, an Evolving Cultural Landscape. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1563 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Rao, X.; Qiu, H.; Morrison, A.M.; Wei, W.; Zhang, X. Predicting Private and Public Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Rural Tourism Contexts Using SEM and fsQCA: The Role of Destination Image and Relationship Quality. Land 2022, 11, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catibog-Sinha, C. Biodiversity conservation and sustainable tourism: Philippine initiatives. J. Herit. Tour. 2010, 5, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, C.; Edwards, S. Linking biodiversity and sustainable tourism policy. In Ecotourism Policy and Planning; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2003; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fjelstul, J.; Fyall, A. Sustainable drive tourism: A catalyst for change. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Stepchenkova, S. Altruistic values and environmental knowledge as triggers of pro-environmental behavior among tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1575–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: How to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaningsih, E.S.; Tjiptoherijanto, P.; Heruwasto, I.; Aruan, D.T.H. Linking of egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric values to green loyalty: The role of green functional benefit, green monetary cost and green satisfaction. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2019, 6, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Uysal, M.; Kim, J.; Ahn, K. Nature-based tourism: Motivation and subjective well-being. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32 (Suppl. 1), S76–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-F.; Fu, C.-S. Changes in tourist personal values: Impact of experiencing tourism products and services. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A. Contributions of sense of place to sustainability in agricultural landscapes. In Proceedings of the International Sociological Association Conference Brisbane, Brisbane, Australia, 7–13 July 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.-C.; Wang, D.; Loverio, J.P.; Liu, H.-L.; Wang, H.-Y. Influence of Attachment Theory on Pro-Environmental Behavior and Well-Being: A Case of Organic Agricultural Tourism in Taiwan Hualien and Taitung. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, J.P.; Cerio, C.T.; Biares, R.R. Tourists’ motives and activity preferences to farm tourism sites in the Philippines: Application of push and pull theory. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2104706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Shi, K.; Xu, S.; Wu, A. Will tourists’ pro-environmental behavior influence their well-being? An examination from the perspective of warm glow theory. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Ma, J. From nature experience to visitors’ pro-environmental behavior: The role of perceived restorativeness and well-being. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseyk, F.J.F.; Small, B.; Henwood, R.J.T.; Pannell, J.; Buckley, H.L.; Norton, D.A. Managing and protecting native biodiversity on-farm–what do sheep and beef farmers think? N. Z. J. Ecol. 2021, 45, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The nature relatedness scale: Linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behavior. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanli, S.; Xin, Z.; Chunhung, L.; Jingbo, J.; Hayat, K.R. Tourists’ Willingness to Pay for the Non-Use Values of Ecotourism Resources in a National Forest Park. J. Resour. Ecol. 2023, 14, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolvanen, A.; Kangas, K.; Tarvainen, O.; Huhta, E.; Jäkäläniemi, A.; Kyttä, M.; Nikula, A.; Nivala, V.; Tuulentie, S.; Tyrväinen, L. Data on recreational activities, respondents’ values, land use preferences, protection level and biodiversity in nature-based tourism areas in Finland. Data Brief 2020, 31, 105724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsony, C.; Bishop, E.; Mulveney, J.; Patel, A. 4. Problematic Overlap of Algonquin Park Eco-Tourism and Most Suitable Habitat for the Protection of Black Bear Biodiversity. In Proceedings of the Inquiry@ Queen’s Undergraduate Research Conference Proceedings, 2018; Available online: https://ojs.library.queensu.ca/index.php/inquiryatqueens/article/view/11699 (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Wartini, S.; Alfaqiih, A.; Riswandi, B.A.; Park, J. The Impacts of Eco-Tourism and Agrotourism Based on Plant Variety Protection to Sustain Biological Diversity and Green Economic Growth in Indonesia. Int. J. Law Politics Stud. 2022, 4, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzek, V.; Wilson, K.A. Public support for restoration: Does including ecosystem services as a goal engage a different set of values and attitudes than biodiversity protection alone? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Gao, Y.; Shen, Q.; Moudon, A.V.; Tuo, J.; Habib, K.N. Does high-speed rail mitigate peak vacation car traffic to tourist city? Evidence from China. Transp. Policy 2023, 143, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, S.; Khan, S. Autonomous vehicles adoption motivations and tourist pro-environmental behavior: The mediating role of tourists’ green self-image. Tour. Rev. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Werdiyasa, I.B.K.S. A journey to be eco-tourism destination: Bali prepared to shift into electric-based vehicle. Bali Tour. J. 2020, 4, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Page, S.J. The Geography of Tourism and Recreation: Environment, Place and Space; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D. The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; Volume 922. [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch, D. Car traffic in a national park: Visitors’ perceptions and attitudes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 96, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; Hanna, P.; Higham, J.; Cohen, S.; Hopkins, D. Can we fly less? Evaluating the ‘necessity’of air travel. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2019, 81, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, Ö.; Göral, M.; Kul, F. Investigation Of Altruistic Value Perception Of Tourists That Impact On The Pro-environment Behavior. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lian, Y.; Dong, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z. Rational planning strategies of urban structure, metro, and car use for reducing transport carbon dioxide emissions in developing cities. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 6987–7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K. Sustainable Tourism: Contribution, Need, Ways and Impact with Special Reference to Jammu and Kashmir. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2019, 7, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zoysa, M. Ecotourism Development and Biodiversity Conservation in Sri Lanka: Objectives, Conflicts and Resolutions. Open J. Ecol. 2022, 12, 638–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshyar, V.; Behboodi, O.; Ahmadi Saeed, S.F. The impact of personal values on pro-environmental behavior. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Stepchenkova, S. The impact of personal values and attitudes on responsible behavior toward the environment. In Travel and Tourism Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally; Travel and Tourism Research Association: Lapeer, MI, USA, 2018; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Tonge, J.; Ryan, M.M.; Moore, S.A.; Beckley, L.E. The Effect of Place Attachment on Pro-environment Behavioral Intentions of Visitors to Coastal Natural Area Tourist Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2014, 54, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R.; Bacon, J. Effects of place attachment on users’ perceptions of social and environmental conditions in a natural setting. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Shen, Y.L. The influence of leisure involvement and place attachment on destination loyalty: Evidence from recreationists walking their dogs in urban parks. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 33, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfman, N.C.; Cisternas, P.C.; López-Vázquez, E.; De la Maza, C.; Oyanedel, J.C. Understanding attitudes and pro-environmental behaviors in a Chilean community. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14133–14152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. Simultaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika 1971, 36, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. (Eds.) Assessing PLS-SEM Results—Part I: Evaluation of the Reflective Measeurement Models. In A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streukens, S.; Leroi-Werelds, S. Bootstrapping and PLS-SEM: A step-by-step guide to get more out of your bootstrap results. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.-W.; Jia, J.-B. Tourists’ willingness to pay for biodiversity conservation and environment protection, Dalai Lake protected area: Implications for entrance fee and sustainable management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2012, 62, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Duim, R.; Caalders, J. Biodiversity and tourism: Impacts and interventions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H.; Spenceley, A. The Success of Tourism in Rwanda—Gorillas and More. In Yes, Africa Can: Success Stories from a Dynamic Continent; Chuhan-Pole, P., Angwafo, M., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 231–252. [Google Scholar]

- Gatersleben, B. Psychological Motives for Car Use. In Handbook of Sustainable Travel; Gärling, T., Ettema, D., Friman, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wong, P.P.W. Purchase intention for green cars among Chinese millennials: Merging the value–attitude–behavior theory and theory of planned behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 786292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarken, R. Authenticity, Autonomy and Altruism: Keys for Transformation. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual Equity Within the Classroom Conference, Houghton, MI, USA, 27–29 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).