Abstract

Traditional Malay houses are a significant part of Malay cultural heritage. They depict local culture, customs, and philosophy and symbolize national identity. As a tourism-based facility, traditional Malay houses contribute to the growth of the economic and tourism sectors in Malaysia. Over time, Malay houses have deteriorated owing to human and natural factors. Modernization and urbanization also threaten the existence of Malay houses. These factors, along with the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, are the main drivers for Malay houses preservation. The aim of this study is to investigate the state of the art in the preservation of traditional Malay houses through a critical review of current practices and challenges. The results show that considerable efforts have been made by different parties to preserve Malay houses. However, the preservation of Malay houses has neither reached a comprehensive status nor achieved the desired goals. For holistic preservation of Malay houses, a multidimensional preservation approach is recommended, in which engineering and technology, socioeconomic, planning, and management dimensions are all addressed simultaneously, consistent with sustainability principles and local objectives. This study identifies key areas where strategic support and improvements are needed to meet the desired outcomes in traditional Malay houses preservation. These include challenges and aspects overlooked in current practices. Therefore, the study findings can be used by policy and decision makers to guide the planning and management of traditional Malay houses preservation. It also contributes to knowledge translation in practice by discussing current preservation practices and recommending a potential preservation approach. This study highlights future research directions.

1. Introduction

Cultural heritage refers to the legacy of cultural resources that society has maintained for many years. This legacy is crucial for the national identity of society [1]. It includes tangible items, such as monuments, buildings, textiles, books, paintings, and archeological artifacts, and intangible attributes, such as history, traditions, language, and performance arts. Heritage conservation is the act of protecting cultural heritage and prolonging its lifespan. Preservation is an approach to heritage conservation that endeavors to delay the deterioration of tangible items and provide buildings with structural safety and well-being [2,3].

Malaysia’s cultural heritage is enriched with buildings with unique designs that reflect the cultural diversity of the country [4]. Traditional Malay houses, the vernacular dwelling of the Malays, represent one of the most significant items of local cultural heritage. They are timber houses raised on stilts [5] and basically consist of a main building unit with a cluster of several building units that have very flexible form [6]. The main unit of the house is distinctive for its largest volume and highest roof [7]. It consists of foundations in a form of plinths made of hardwood or concrete stumps [8], rectangular frame of posts and beams and trussed roof assembled with complex joint system. [9]. Traditional Malay houses are constructed of highly durable timber species, commonly Chengal wood (Neobalanocarpus heimii) [10]. Figure 1 shows that a typical traditional Malay house has a dual pitch, steep roof [5], with aesthetic forms expressed in a combination of geometrical shapes, lines, and curves [11]. Traditional Malay houses have open spaces, classified based on their functions and defined by floor level change with the absence of walls for ventilation and lightning purposes [8,12]. They show regional variations through a set of unique styles that are mainly recognized by their distinctive roof shapes. Traditional Malay houses not only reflect the indigenous architecture and local philosophy of the Malays [13] but also meet the Malays’ socio-economic, cultural, and environmental needs [5].

Figure 1.

Basic characteristics of traditional Malay houses. Source: Author.

Traditional Malay houses, like other heritage structures, are exposed to different potential risks in their surrounding environments. The aging process, adverse environmental conditions, and attacks by biological organisms are examples of these risks [14]. Unfortunately, climate change negatively affects heritage timber structures. Traditional Malay houses are constructed with timber and are impacted by climate change. Variations in temperature and humidity are among the characteristics that result from climate change. Timber interactions with these variations are exhibited via shrinkage and swelling cycles, as well as through decreased timber stiffness and resistance [15].

An interaction also exists between traditional Malay houses and natural hazards associated with climate change such as floods. The World Bank Group Report for 2021 states that extreme flood events have recently increased in Malaysia in terms of severity and frequency. These events are projected to continue to increase due to increased rainfall; this increase is attributed to temperature rise and global warming. Human evacuation, home destruction, property losses, and historic and cultural losses occurred in Malaysia in 2021 due to flash floods that hit the country [16]. The following year, the country witnessed another set of floods with similar adverse consequences. Newspapers and social media captured many photographs of traditional Malay houses that were destroyed and swept away by the floods.

Development and modernization have influenced the cultural structure of the Malaysian society and induced social change. This influence has modified Malaysian lifestyles and views. Malays now tend to prefer having a modern house to a traditional Malay house, putting the latter at risk of abandonment and lack of maintenance [17].

The tourism industry in Malaysia began using Malay heritage components to develop the sector. Since the adoption of this strategy, traditional Malay houses have contributed to the economic achievements of the tourism industry [18]. Many traditional Malay houses are used as tourism-based facilities, as seen in the Terrapuri heritage village in Trengannu and Daun Resort in Langkawi. In addition to their roles in the economic and tourism sectors, traditional Malay houses have a significant sociocultural value. Local philosophies, traditions, customs, and lifestyles are reflected in the designs of the houses. As symbols of national identity, traditional Malay houses also contribute to the social cohesion.

Societies worldwide have recognized the need to preserve their valuable cultural heritage [19], and decision makers have emphasized heritage preservation as represented by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030. SDG 11 addresses sustainable cities and communities, with the aim to “make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable”. SDG 11 provides a comprehensive framework for heritage buildings, particularly Target 11.4, which seeks “to strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage”. Heritage preservation also helps to reduce landfill waste, demolition energy use, and resource consumption for new constructions [20]. This is consistent with SDG 12, Target 12.5: “by 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse”. Therefore, comprehensive heritage preservation in Malaysia will support the achievement of SDGs 11 and 12.

The potential risks to which traditional Malay houses are subjected, the social and economic importance of the Malay houses, and sustainability drivers make the preservation of traditional Malay houses a pressing need. With a focus on the effective preservation of traditional Malay houses, this study aims to investigate the state of the art of traditional Malay house preservation through a critical review of current practices and challenges. In this paper, Malay house preservation practices and challenges are contrasted with ideal practices to advance interdisciplinary collaboration between all parties engaged in the preservation of traditional Malay houses, with an emphasis on the structural engineering field. This is in line with the significant efforts undertaken to protect Malaysia’s cultural heritage.

2. Concept of Preservation

Heritage conservation represents all actions performed to mitigate the deterioration of historical buildings and manage the changes to which they are subjected. Preservation is one of the several approaches to heritage conservation. It deals with the maintenance of a heritage structure in its existing state [21] by halting its dilapidation [2]. Structurally, preservation intends to provide a building with structural well-being and safety and stabilize its materials and features [2,22]. Preservation can involve doing little or nothing [23], performing repairs when necessary [21], or conducting full transformation [24]. Heritage conservation is a broader concept [25] that includes restoration, rehabilitation, reproduction, and reconstruction, in addition to preservation. However, “conservation” and “preservation” are often used interchangeably to refer to the protection of heritage structures and the preservation of their original nature.

Preservation of a heritage structure demands specialized professional expertise to preserve its physical components [25]. This involves a multidisciplinary team of professionals with structural, electrical, mechanical, and architectural backgrounds. Its effectiveness is influenced by the level of knowledge and skills in architectural history, building pathology, preservation techniques, and repair materials. Preservation is performed according to specified standards and guidelines to ensure that the authenticity of the heritage structure is not violated [26].

Principles for the Conservation of Wooden Built Heritage 2017 document by the International Council on Monuments and Sites, ICOMOS, shaped the global perspective of wooden built heritage conservation by defining the basic principles and practices applicable internationally to safeguard historic timber structures. This document represents an updated version of its counterpart adopted by ICOMOS in the 12th General Assembly, in Mexico, 1999. It takes into consideration the general principles of the Vence Charter 1864, the Declaration of Amsterdam 1975, the Burra Charter 1979, the Nara Document on Authenticity 1995, and relevant ICOMOS and UNESCO doctrines. The document principles focus on the recognition of the importance of the wooden built heritage and the evidence they provide on the skills of craftworkers, respecting their diversity and understanding the continuous evolution of their cultural values over time. They request consideration of the excellent behavior of these structures in withstanding some natural forces and their vulnerability under varying environmental conditions. The principles of ICOMOS also highlight the increasing loss of wooden heritage structures and insist on respecting different local traditions and conservation methodologies with an emphasis on community participation in the preservation of these structures [27,28].

The ICOMOS Principles for the conservation of Wooden Built Heritage document 2017 demonstrated the necessary actions that the correct preservation process of a historic timber structures includes. Among these actions, which were also referred to by Terlikowski [28] in his study about historic wooden structures in Poland, and mentioned by Larsen, and Marstein [29] in their book “Conservation of Historic Timber Structures”, are the following:

- Inspection, survey, recording, and documentation.

- Analysis and evaluation of structural and non-structural elements.

- Analysis of physical condition defects.

- Regular monitoring and ongoing maintenance.

The emergence of advanced technologies has reshaped the concept of preservation and offered alternatives for preservation of built heritage [19]. Preservation, which is widely known as keeping cultural heritage components physically intact against the factors that attempt to change them, nowadays aims to save a copy of the component either physically or virtually. Virtual preservation uses technologies, such as virtual reality, to preserve a digital copy of heritage structures in digital databases.

In the Malaysian context, the preservation of heritage structures mostly follows the same practices as above, but not all of these practices are equally used in traditional Malay houses preservations.

3. Evolution of Traditional Malay House Preservation and Current Practices

Heritage conservation practices in Malaysia date back to the 16th century. At that time, no conservation movement had emerged. However, customary traditions have driven conservation practices in the form of heritage structures relocation [30]. Nevertheless, conscious conservation works started in Malaysia much later than in Europe [31]. In 1945, General Sir Gerald Templer made a policy speech emphasizing the preservation needs of Peninsular Malaysia’s arts and crafts. His speech sparked a conservation movement [10], which led to the establishment of the Arts Council of Malaysia in 1952 [32]. The Council has played an effective role in encouraging the conservation of heritage treasures in Malaysia. The earliest recorded historical building conservation projects in Malaysia involved structural relocation. In 1953, the Ampang Tinggi Palace, the first historical building to be officially conserved, was restored and reused as the Negeri Sembilan State Museum. Almost 10 years later, the Istana Tengku Long Palace was conserved, and in 1967, a conservation project was executed to safeguard the Kampung Laut Mosque [10].

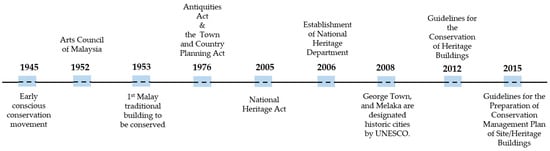

The federal and state government introduced acts and decrees, such as the Antiquities Act 1976 and the Town and Country Planning Act 1976, to grant local heritage conservation [31]. The Heritage of Malaysia Trust 1993 and National Heritage Act 2005 were released and enacted for the same purpose too [1]. In 2006, the National Heritage Department was established under the National Heritage Act. After two years, UNESCO designated George Town and Malacca as World Heritage Sites because George Town and Malacca fulfill the second, third, and fourth Outstanding Universal Value Criteria. Since then, heritage conservation has attracted the attention of many Malaysian parties [33,34]. The Guidelines for the Conservation of Heritage Buildings (2012) and Guidelines for the Preparation of Conservation Management Plan of Site/Heritage Buildings (2015) were prepared and published by the National Heritage Department. The purpose of these guidelines is to support the conservation of heritage buildings and sites [1] and ensure that all conservation practices are in accordance with the 2005 National Heritage Act [35]. Figure 2 presents the major milestones of heritage conservation in Malaysia.

Figure 2.

Major milestones of heritage conservation in Malaysia.

The conservation of heritage structures in Malaysia is pursued in collaboration with other sectors to contribute to the country’s development. For example, a mutualistic relationship connects heritage structure conservation with tourism. According to Mustafa et al. [4], heritage structures promote heritage tourism because they strongly motivate heritage tourists interested in cultural uniqueness and historical and architectural values to visit Malaysia. Statistics have shown that 31.9% of the main activities by tourists involve visiting historical sites [36]. At the same time, heritage tourism contributes to conserving heritage structures. Heritage structures conservation has gained increased attention and efforts to promote the tourism sector and increase revenue generation [37]. Many tourism- conservation projects have been designed based on this relationship. In these projects, heritage structures are preserved, maintained, and used simultaneously as tourism-based facilities. For example, the Terri Puri Heritage Village in Terengganu protects approximately 29 100-year-old antique, classic houses while being a spectacular recreational destination for many local and international tourists. Because feedback from tourists regarding tourist attractions is valuable for the prosperity of the tourism sector, researchers such as Hasshim et al. [38] and conservators have employed tourists feedback in preserving traditional Malay houses. Framework for measuring tourists satisfaction regarding traditional Malay houses preservation and landscape characteristics have been proposed [38]. However, the impact of authenticity, which refers to the sense of being real, cultural, and connected to the past [39], on the emotions, satisfaction, and feedback of the tourists have not been considered.

The preservation of traditional Malay houses differs from those of other heritage structures, as they are in use by occupants. Researchers such as Tan [34] and conservators have recognized this and started to implement hybrid preservation in Malay villages. Hybrid preservation enables villages to be inhabited and function as open-air museums simultaneously. This guarantees the preservation of traditional Malay houses, preventing them from being abandoned or demolished by reconstituting and urbanizing traditional Malay villages. Residents of Malay villages have interacted positively with hybrid preservation. Rahman et al. [40] showed that the residents of Kampong Morten in Malacca welcomed the conservation of their village as a living museum.

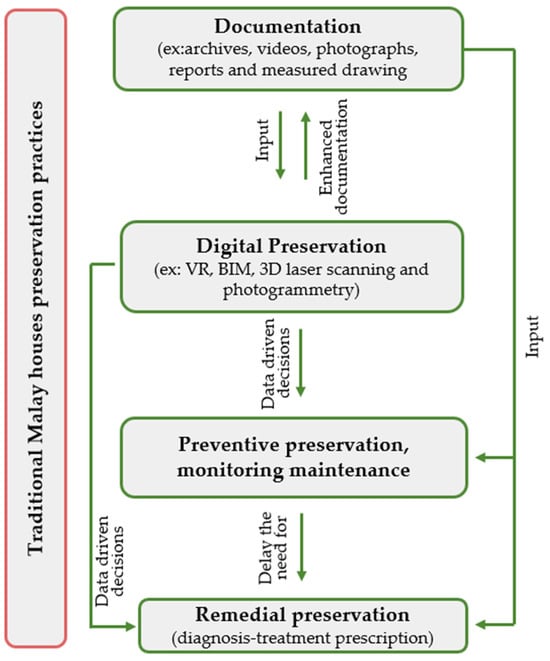

Based on the approach adopted, practices that aim to preserve traditional Malay houses can be divided, as shown in Figure 3, into documentation activities, remedial actions, preventive measures, and the implementation of digital technologies. These practices are discussed in the following subsections.

Figure 3.

Current practices in preservation of traditional Malay houses.

3.1. Documentation

The dominant practice in traditional Malay house preservation is documentation, through which the preservationist studies and captures information related to different aspects of a traditional Malay house, such as its history and physical characteristics. The preservationist then provides detailed descriptions of these aspects in the form of systematic collections, archives, videos, photographs, reports, measured drawings, and published research papers. The Center for the Study of the Built Environment in the Malay World, KALAM, has a database rich in a documentary collection of historical buildings in Malaysia, including traditional Malay houses [31]. Preservationists of various profiles contribute to traditional Malay house documentation, with architects constituting the majority. Through documentation, traditional Malay house design elements, architectural styles, ornaments, construction components, construction technology, materials, history, and cultural values are recorded and stored for future generations.

Traditional Malay housing styles are the features of houses that have been extensively documented. These styles have been traced back and discussed in the contexts of ethnography and culture. The evolution of these styles has been described, and their unique design features have been recorded, as in the case of the traditional Malay house of Perak State [41]. Other efforts tend to document traditional Malay house styles by establishing a parametric shape type [42] or a typological rule system [7] to construct the house style. Ornaments, which are unique characteristics of the Malay house that reflect its aesthetic value, have also been examined, recorded, and compared in terms of various styles [43]. The best example of documentation is that of the traditional Malaccan house [44].

The traditional Malay house represents a simple but effective house model designed to suit Malay needs, culture, and tropical climate [45]. Preservationists, particularly architects, have investigated and documented the design elements of the houses in relation to the local environment, specifically sociocultural [12] and economic conditions [5]. They have also recorded climate stress-relief devices in the houses in relation to Malaysia’s climate. This documentation theme has attracted the attention of many architects, including Sung [8], Kamal [5], and Hidayahtuljamilah et al. [46].

The structural aspects of the traditional Malay house are still under-documented, as they have not received as much effort as the design and architectural features. Some studies have recorded Malay houses from a structural perspective. However, these records are mainly products of architectural studies conducted by architects, not structural engineers. Details regarding the structural systems of the different styles of Malay houses and their types of foundations are scanty, if not absent. In addition, the structural drawings, plans, sections, and detailing are simple, and these were prepared by architects. The available structural documentations of traditional Malay houses highlight only the construction technology and mortise joints, mainly in terms of the historical background, types, uses, importance, and production methods. These records present the formation of the mortise types used in traditional Malay houses; they also clarify the relationship between the type and location of mortises and the design and strength of the houses [47].

As a preservation practice, documentation provides accurate and timely information that promotes structural preservation, monitoring, and maintenance [48]. The European experience in timber heritage structures preservation also includes the documentation of these structures. A good example is that from northern Europe where documentation was used in the preservation of Karelia’s ancient wooden structures. Similar to traditional Malay houses, the documentation of Karelia’s traditional timber architecture, recorded details about construction techniques and architectural features of these structures [49].

Despite efforts to record traditional Malay houses, comprehensive and complete documentation of the houses has not been achieved yet. Documentation projects for traditional Malay houses are small and insufficient. According to Tan [34], this can be attributed to the lack of basic understanding of documentation and the high costs involved, which make comprehensive documentation exclusive to specific heritage conservation projects in Malaysia.

3.2. Preventive Preservation, Monitoring, and Maintenance

Preventive preservation refers to practices aimed at preventing dilapidation and damage [50]. The regular inspection, monitoring, and creation of ideal surrounding conditions with small-scale repairs are the core of preventive preservation. The Athens Charter in 1931 and the Venice Charter 1964 advocated preventive conservation, which managed to gain importance only in the last 15 years. [51]. The preventive preservation efforts for traditional Malay houses can be subdivided into two groups, based on the approach used to preserve the houses. One group depends on monitoring and regular inspections, and the other explores innovative ways to create ideal conditions for dilapidation mitigation.

Regarding the monitoring and inspection aspects, actions are taken to propose an appropriate inspection and monitoring approach; although, these actions are fewer in number [52]. These actions compromise the involvement of house owners as a significant party in the preservation process. The house owners are empowered and trained to perform regular inspections and maintenance of their houses and adopt appropriate measures [52]. Such preservation practices, although lacking the focus and skills required to resolve the damage to structural elements, raise the awareness of the community in heritage conservation; this is as important as the preservation work [53]. Furthermore, this demonstrates that citizen participation is a potential mechanism in preserving traditional Malay houses to achieve sustainable development, consistent with the modern preservation approach described by Curcic et al. [53]. The case is the same in the South-West Europe. Projects, such as The HeritageCARE project, are organized with the aim of outlining proper methodology for the preventive conservation of cultural heritage structures. Such projects arose in response to the shortcomings of the preventive conservation in the South-West Europe represented by intermittence and lack of methodical strategy [54].

The approach of creating ideal conditions for dilapidation mitigation of the houses is rarely observed in Malaysia. A possible method for achieving this is to interfere with the constituents of the construction materials of the houses. To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, only one study adopted this approach [55], targeted the preservation of the Singgora roof, a type of roof used in some traditional Malay houses, and made of original local clay. This study aims to improve the strength and durability characteristics of the roof and minimize surface defects by modifying the ingredients of its construction materials. It investigated the effect of adding grog, a pre-fired clay as a strengthening agent, glazes as a durability treatment and Copper and Cobalt Oxides for coloring, on the characteristics of the roof [55]. The question remains whether such modification violates the authenticity of this unique type of roof. This might be the reason that no other efforts with such practices could be tracked.

3.3. Remedial Preservation

This preservation practice is based on a diagnosis–treatment prescription approach. Dilapidation surveys are conducted in houses of interest. The literature, artifacts, archives, and measured drawings are also reviewed to diagnose the damage to houses and identify the underlying causes. Next, treatments are recommended to remediate this damage. The preservation practice adopted by Latip et al. [56] to preserve a set of traditional Malay houses falls within this category. Based on the assessment results of their study, which included structural and nonstructural members, they identified the defect types, defect locations, and defect causes and subsequently recommended appropriate treatments to protect the investigated houses. Unfortunately, preservationists who practice this approach ignore the altered structural behavior of the house resulting from damage or remedial measures. Assessing the structural behavior of the damaged house, before and after applying the remedial measures, can demonstrate the effectiveness of the remedial measures and reduce the measures to a minimum, which is favorable in terms of authenticity.

In Europe, unlike in Malaysia, guidelines that outline the principles and possible approaches of the safety assessment of historic timber structures were produced by the European Cooperation in Science and Technology—Wood Science for Conservation of Cultural Heritage (COST IE061-WoodCultHer). The purpose of the guidelines is to ensure that the assessment and inspection process yield the needed data for structural safety assessment and proper planning of preservation interventions [31,57].

3.4. Digital Preservation

Preservation of heritage structures in the virtual sphere may weaken the interpersonal connection with traditions and may not give a true reflection of history like preservation in the real sphere does [58]. However, digitalization and advanced technologies have played a significant role in the preservation of heritage structures. They have eased the labor-intensive manual documentation [59] and introduced a new level of details. When employed in built heritage preservation, advanced technologies are cost effective, very flexible and provide high-quality 3D virtual models. Computer graphics, virtual reality, augmented reality, digital databases, 3D laser scanning, photogrammetry, and building information modeling (BIM) are examples of digital technologies that are widely used alternatives for preserving timber heritage structures, including the traditional Malay houses. Three-dimensional laser scanning uses laser beams to capture accurate details about heritage structures and create a digital replica. It helps in documenting dilapidated or inaccessible parts of heritage structures [59]. It also enables careful assessment of the built heritage structural integrity [60]. Photogrammetry is another advanced technology that captures multiple precise images and utilizes overlapping of these images to create a 3D model of heritage structures. This tool is very useful for virtual exploration and in-depth analysis [59]. When it comes to BIM, its ability to simulate various scenarios virtually makes this technology very helpful in data driven decision making in heritage structures preservations especially when it comes to decisions related to elements repair and replacement [61].

Many studies digitalized traditional Malay houses as a step towards preserving their architecture and physical attributes. Among the efforts to digitally preserve traditional Malay houses is the extensive investigation by Mustafa et al. [9], who proposed an approach for the historic BIM library of traditional Malay houses in Perak and Selangor. In addition, Nazrita and Khairul Azhar [62] developed a virtual 3D model of Rumah Tek Su, a traditional Malay house in Kedah, using polygonal geometry, rendered images, and digitalization. Their final virtual 3D model reflected the architectural essence of the heritage and showcased its beauty. Similarly, Harun and Yanti [63] developed an application that offers a 360° virtual tour of a traditional Malay house with a panoramic effect. The tour resembles a real-life experience and includes the physical attributes of the house. When the tour begins, users can obtain information about the traditional Malay house and explore images of its unique parts. Teratak Zabaa, a traditional Malay house in Negeri Sembilan, is another example of traditional Malay houses that have been digitalized [19]. The geographic information system, which helps understand the relationship between the heritage structures and their surroundings, is used as a digital archive to preserve and manage Malacca’s heritage buildings [19]. Currently, digital technologies enable users to access a digital reconstructed copy of a typical traditional Malay house, navigate the three-dimensional (3D) environment of the house, and experience its architectural textiles, regardless of the location and existing conditions of the house [17].

Examples implementation of the above digitalization tools in heritage preservation from other countries is the use of 3D laser scanning for the preservation works of Pawlowice palace in Poland [28] and Fadum Storehouse and Heierstad Loft in Norway [64].

Table 1 describes in brief preservation practices discussed above, clarifies their limitations, and points out which of these practices are dominantly used. It also lists traditional Malay house aspects preserved by each of these practices. Table 1 highlights the key aspects of traditional Malay houses that are overlooked and need more attention and contribution from the concerned parties too.

Table 1.

Practices, their popularity, and domains in traditional Malay house preservation.

4. Challenges in Traditional Malay House Preservation

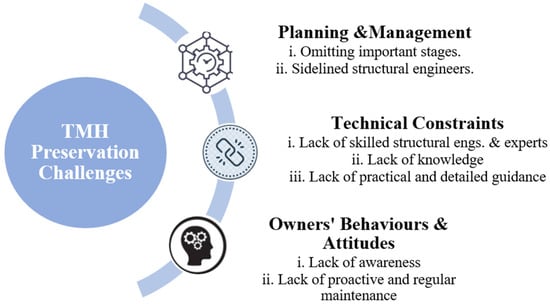

A clearly specified set of challenges is the basis for identifying possible workarounds and designing efforts to overcome obstacles that hinder preservation progress. Issues and challenges experienced in traditional Malay house preservation have been highlighted by many researchers such as Harun [2], Sulaiman [31], and Abdul Rahman et al. [65]. Based on their findings, these challenges can be divided into three groups: planning and management, technical constraints, and owners’ behavior and attitudes (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Challenges in preservation of traditional Malay houses.

4.1. Planning and Management

Any heritage preservation project requires an appropriate and precise plan that follows standards and guidelines. In local preservation projects, including traditional Malay houses, contractors may be careless during the planning and preservation stages. The time taken to plan, conduct a geometric survey, collect data, and perform tests is shortened. For example, some contractors used to omit the dilapidation stage of preservation projects [2] and make conservation decisions based on assumptions. Such a rush in performing repair and preservation actions leads to the risk of further damage and loss of cultural and historical values [2]. This might also introduce obstacles during later stages of the preservation process. In addition, structural engineers are usually sidelined during the decision-making process of Malay house preservation; they play a minimal role in these projects, which may lead to unnecessary remedial interventions or structurally unsafe traditional Malay houses.

4.2. Technical Constraints

4.2.1. Lack of Skilled Heritage Structural Engineers and Technical Experts

Preservation practices are highly observable, and their success and failure are significantly influenced by the practitioners’ skills [3]. Harun [2] and Sulaiman [31] found that the lack of skilled laborers and experts is a significant challenge facing preservation works in Malaysia. Conservators and technicians, particularly structural engineers, experience difficulties in defect diagnosis and decision-making regarding preservation techniques. This is attributed to the complex and diverse contexts inherent in such projects, represented by the material properties, decay process, underlying uncertainties, and the absence of supportive knowledge [3]. Preservation projects of traditional Malay houses are few, resulting in insufficient opportunities for the training of structural engineers and preservationists from other profiles. As preservation works performed by nonexperts can increase the level of damage to structures by up to 50% [52], training structural engineers to function effectively in a multidisciplinary team is critical for the successful of preservation of traditional Malay houses. This includes equipping the structural engineers with the necessary skills in defect diagnosis and selecting appropriate preservation techniques and materials.

4.2.2. Lack of Knowledge

Many techniques for preserving heritage structures are traditional methods transferred from one generation to the next. These methods are at risk of disappearing if not well disseminated and documented [3]. This is the same case for the preservation of traditional Malay houses. Forums within heritage conservation institutions, where practitioners and technicians can organize themselves in professional groups based on their experiences, are good opportunities to circulate knowledge and generate discussions. In practice, the exchange of knowledge between structural engineers and other practitioners relevant to traditional Malay house preservation is limited, unless motivated by a specialized research capacity. However, there is a lack of consensus regarding the scientific knowledge [33] required to support preservation activities, particularly in terms of structural engineering. Structural engineers, preservationists, and technicians require knowledge that will assist them in the decision-making process in achieving traditional Malay house preservation. In addition, structural engineers must be familiar with conservation principles to function effectively in Malay house preservation projects. It is imperative to develop strategies to summarize and share existing knowledge. The conclusions of academic research should be considered in practice and disseminated beyond academia to achieve the desired impact in Malay house preservation.

4.2.3. Lack of Practical and Detailed Guidance

Appropriate guidelines and technical manuals are essential for practitioners. Malaysia has two main conservation guidelines: Guidelines for the Conservation of Heritage Buildings (2012) and Guidelines for the Preparation of Conservation Management Plan of Site/Heritage Buildings (2015) [1]. Despite the existence of these guidelines, the National Heritage Act, and many other legislations and trusts, conservation practices in Malaysia have not achieved the desired outcomes. A crucial cause is the lack of clear guidance for managing the maintenance of heritage buildings [37]. In addition, these documents are generic and do not provide specifications for Malay house preservation.

Structurally, many generic standards and codes define structural demands and limitations for newly designed and existing buildings but not for heritage structures [66]. Full compliance with these standards will undoubtedly lead to heavy interventions in traditional Malay houses, regardless of whether the house is damaged. Therefore, structural engineers need standards that focus on the analysis of traditional Malay houses and the design of interventions, considering conservation principles. Such standards should establish different performance levels that satisfy minor preservation interventions. The preservation of traditional Malay houses can be more effective and sustainable if preservationists, technicians, and structural engineers refer to comprehensive guidelines.

4.3. Owners’ Behaviors and Attitudes

4.3.1. Lack of Awareness

Because they are inhabited heritage structures, the preservation of traditional Malay houses is influenced by the occupants. The lack of awareness of the importance of traditional Malay houses and their values among the house owners and the owners’ attitudes hinder the preservation [10,31,67]. For example, many house owners prefer to wait until damage occurs before taking any preservation or maintenance action on their houses. This leads to more damage to the houses, losses in authenticity, and consequently, potential losses in heritage resources [65].

4.3.2. Lack of Proactive and Regular Maintenance

Regular maintenance is the most important practice for preserving heritage structures [37]. Poor maintenance of traditional Malay houses leads to severe defects and adversely affects the structural safety of the houses. Therefore, the preservation of traditional Malay houses as an iconic legacy must be raised to the level of the owners’ primary duty. Programs that educate house owners to recognize the heritage values of their houses and train them to conduct regular maintenance, such as the program-based research of Kayan [52], are among the best solutions. In addition, hybrid preservation guarantees owners’ good attitude, as the owners will regularly look after their houses to maintain the high quality of Malay villages and attract visitors to their open-air museums.

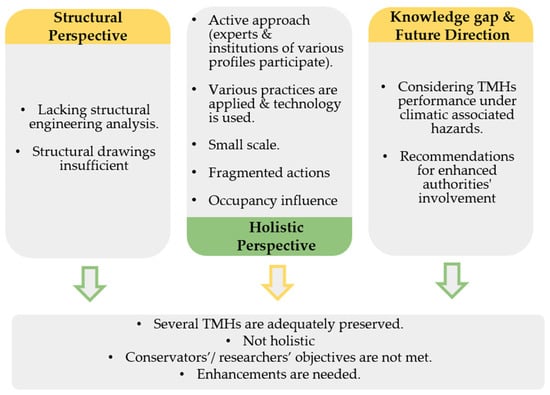

5. Where Does Traditional Malay House Preservation Stand?

5.1. Structural Perspective

Efforts to preserve traditional Malay houses have rarely focused on structural engineering aspects. Preservation dealing with diverse structural features, such as discrete structural element modeling, linear and nonlinear finite element analyses, and collapse-load limit analyses, is lacking. Engineering studies and drawings of structural systems of the traditional houses are primitive, insufficiently developed, and prepared by architects. Hence, interventions for traditional Malay house preservation were designed and planned without structural considerations or analysis. This may lead to ineffective interventions and plans, excessive or insufficient fund allocations, excessive or insufficient interventions, and delays in intervention implementation [66]. When empowered and provided with opportunities, structural engineers can play crucial roles in preserving traditional Malay houses.

5.2. Holistic Perspective

Several traditional Malay houses have been adequately preserved, protected, and maintained. An interpretive overview of the house preservation process shows that different segments of society apply various preservation practices to maintain Malay houses. Recent technologies have been used for this purpose. Generally, the preservation of traditional Malay houses can be regarded as an active approach. According to Curcic [53], this means that institutions and experts of various profiles contribute to house preservation. The preservation of Malay houses is characterized by a set of features, as shown in Figure 5. Being mainly exclusive to major heritage buildings in Malaysia, conservation projects that deal with traditional Malay houses are still small-scale; this is more evident with the rapid disappearance of many traditional Malay houses. The fragmentation of preservation actions is another significant feature of preservation efforts to protect the houses. Each study, action, and preservation program deals with a single value of the house without considering the other values inherent in such precious items of local heritage. For example, the preservation process considers preserving a house based only on its economic or cultural value, excluding other critical aspects.

Figure 5.

Preservation status of traditional Malay houses.

Because it is challenging to control the effects of the daily practices of occupants living in heritage buildings [53], the needs of professional communities dealing with the preservation of these buildings are difficult to satisfy. Traditional Malay houses are no exception to this trend. On the one hand, the aim of preservationists is to maintain the original appearance and functions of traditional houses; on the other hand, many houses are dismantled, rearranged, and replaced by modern houses [31] according to the occupants’ preferences.

The preservation process of traditional Malay houses within its current context, characteristics, and framework is not holistic and has not achieved the objectives of conservators and researchers. There are gaps to be covered, challenges to overcome, and efforts to be made to enhance the effective, comprehensive, and sustainable preservation of traditional Malay houses.

5.3. Knowledge Gap and Potential Future Directions

5.3.1. Marginalized Role of Structural Engineers

Most actions on traditional Malay house preservation are performed by architects, conservators, technicians, and professionals from the social sciences and information technology fields, who do not have the requisite experience and skills to solve structural engineering problems pertaining to heritage conservation projects. Because these professionals are unfamiliar with the structural engineering aspects, their misconceptions, regarding the hazards associated with Malay building structures, the structural performance of the house, and the structural consequences of a particular intervention, have an adverse effect. If no structurally effective solution is developed, many conservation projects may be halted [26] or lead to a waste of funds. In addition, structural engineers frequently find themselves in a disadvantaged position or are sidelined in a multidisciplinary team [66]. Their opinions and decisions are misguidedly viewed as conflicting with conservation principles. The marginal role of structural engineers in the preservation of traditional Malay houses has led to officials and researchers, such as Shabani et al. [68] and Latip et al. [56], calling for the efficient involvement of structural engineers and structural analysts in this process. It is essential to investigate the structural system and configuration of traditional Malay houses and evaluate their structural behaviors at different types of risks to effectively preserve traditional Malay houses. This requires structural engineering knowledge and skills and the application of structural analysis [68]. Therefore, the involvement of structural engineers in heritage preservation projects is essential [56].

5.3.2. Natural Hazards Associated with Climate Change

Malaysia has a hot, humid climate. Recently, an increase in mean surface temperature and rainfall trends has been recorded. Future rainfall projections indicate that extreme rainfall events are likely to increase, particularly in terms of intensity. The same trend is forecast for the mean temperature. Regarding natural hazards associated with climate change, Malaysia has a relatively high exposure-risk level for floods. Existing records show evidence of an increase in flood frequency and extremity in Malaysia in recent decades [69]. These critical climatic conditions and climate-related natural hazards have adversely affected the existence of traditional Malay houses. They are beyond consideration of the house design at the time of the house construction. Questions regarding the structural response of traditional Malay houses to these emerging conditions, their ability to withstand the conditions and hazards, and their capability to recover from consequent damaging effects have not yet been answered. This gap is an emerging issue that requires urgent attention from researchers [70].

5.3.3. Authorities Role

Known for their vital role in preserving traditional Malay houses as identity and an economic source, authorities in Malaysia are the most significant place where enhancements for preservation process can be started. Different levels of authorities in Malaysia are involved in heritage preservation. These authorities manage, monitor, and protect heritage buildings through enactment and implementation of national polices and acts, funding of research and training programs [71] and promoting heritage tourism.

Therefore, recommendations have been made to empower the role of authorities in safeguarding traditional Malay houses. These recommendations include gathering a conservation team dedicated for monitoring, maintenance and documenting traditional Malay houses, raising the awareness of the owners about the significance of these treasures, and training students and public with traditional skills through collaborations with educational institutions [31]. Coordinating research in traditional Malay houses conservation and disseminating insights and knowledge beyond academia are other actions that can receive more support from concerned authorities.

6. Possible Way Forward: Multidimensional Preservation of Traditional Malay Houses

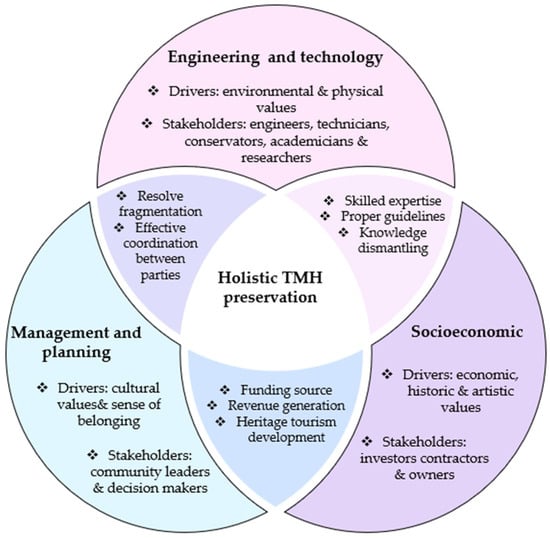

Multidimensional preservation, characterized by the simultaneous involvement of various profile experts and the effective engagement of structural engineers, is a powerful approach. It encompasses addressing all dimensions: engineering and technology, socioeconomic, planning, and management (Figure 6); these dimensions are addressed simultaneously according to the objectives of the local community and sustainable pillars [72]. This approach requires structural engineers to be trained regarding their crucial role in preserving Malay houses and equipped with the skills and tools required for houses preservation. It also entails considering all the values embedded in traditional Malay houses, as these values are the main drivers of a diverse stakeholder set. The more values are considered jointly, the more funding, support, and skills of capable parties will be drawn, and the more efficient and sustainable the preservation of Malay houses will be. Multidimensional preservation leads to the development of different forms of partnership. This enables costs, risks, and benefits to be shared and allocated to different parties [72] based on which party is best suited to take them or which party has the greatest interests and capabilities to maximize the potential returns that may occur due to Malay house preservation. This, in turn, accelerates and strengthens the preservation of traditional Malay houses.

Figure 6.

Multidimensional preservation of traditional Malay houses.

The main drivers of the engineering and technology dimension are the environmental and physical values of the traditional Malay houses. For example, houses are generally characterized by their specific designs that suit the tropical environment of Malaysia. It is provided with many climate stress relief devices and thermal comfort elements [73], which make the house a sustainable piece of architectural design. Such environmental values, if considered along with other values, will motivate technicians, conservators, and marginalized engineers to be efficiently involved in the preservation process of traditional Malay houses. Within the socioeconomic dimension, the economic, historic, and artistic values of the houses promote the engagement of the private sector, real estate investors, contractors, house owners, and the local community in house preservation. The socioeconomic dimension gives these stakeholders the opportunity to invest in the preservation of traditional Malay houses based on their capabilities and interests. It also ensures sufficient space for all concerned parties to participate. Community leaders and decision-makers, driven by cultural values and a sense of belonging, lead the management and planning dimension. They harmonize various interests, organize complex relationships, and coordinate connections among multiple players of preservation. This dimension allows community leaders and decision-makers to strengthen planning and management schemes and resolve fragmentation. Moreover, this dimension creates a balance against the socioeconomic dimension by ensuring that the preservation process is not biased by a particular sector’s interests and that all interventions are executed in accordance with standards [72].

7. Conclusions

Traditional houses are among the most important housing typologies and represent the richest component of a society’s cultural heritage. In Malaysia, traditional Malay houses symbolize national identity and reflect traditional Malay beliefs, customs, and philosophies. It inherits social, historical, artistic, and economic values that benefit the country. Within the surrounding environment, the Malay houses are exposed to potential risks that threaten their existence and cause deterioration. Adverse climate change events, development, modernization, and urbanization are some examples of risks that contribute to the vanishing of traditional Malay houses. The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals that emphasize heritage structure conservation, along with the risks imposed on traditional Malay houses and their significance, support the need to preserve them. The preservation of traditional Malay houses has attracted the attention of various parties who have adopted different preservation practices, such as documentation, preventive preservation, monitoring and maintenance, remedial preservation, and digital preservation. However, the preservation of traditional Malay houses is still limited and experiences fragmentation. Each preservation attempt addressed only one value, aspect, or dimension. In addition, several challenges limit the holistic and comprehensive preservation of traditional Malay houses. Technical constraints, owners’ attitudes, poor planning, and knowledge gaps are among these challenges. A possible approach to effectively and holistically preserve traditional Malay houses is a multidimensional preservation approach that emphasizes the effective engagement of structural engineers. In this approach, all values embedded in the houses are considered jointly, and preservation dimensions are addressed simultaneously in a manner that suits local objectives and sustainability goals. This study provides conservators, technicians, and researchers with insight into the current status of the practices and challenges in preserving Malay houses. This will help preservationists of various profiles plan their preservation efforts well to achieve the desired results. This study proposes a way forward for the improved, effective preservation of traditional Malay houses. Possible areas that warrant further investigation within traditional Malay houses preservation include the following:

- Evaluating the effectiveness of available legislation and guidelines in preserving traditional Malay houses.

- Establishing the mutualistic relationship between heritage tourism and traditional Malay house preservation.

- Investigating the authenticity connection to traditional Malay houses preservation and exploring the impact it has on designing and planning of preservation interventions of these houses.

- Studying traditional Malay houses performance under possible potential risks such as biological attack and fire.

- Investigating the effects of deterioration on the mechanical properties of traditional Malay houses as a timber heritage structure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.M., H.B.H., M.F.S. and H.A.M.; methodology, S.A.M.; formal analysis, S.A.M., H.B.H., M.F.S. and H.A.M.; investigation, S.A.M. and H.A.M.; resources, S.A.M. and H.B.H.; data curation, S.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.M.; writing—review and editing, S.A.M.; visualization, S.A.M. and H.A.M.; supervision, H.B.H. and M.F.S.; project administration, H.B.H. and M.F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mat Nayan, N. Conservation of Heritage Curtilages in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harun, S.N. Heritage Building Conservation in Malaysia: Experience and Challenges. Procedia Eng. 2011, 20, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, J. Heritage Conservation Future: Where We Stand, Challenges Ahead, and a Paradigm Shift. Glob. Chall. 2022, 6, 2100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, N.K.F.; Johar, S.; Ahmad, A.G.; Zulkarnain, S.H.; Rahman, M.Y.A.; Ani, A.I.C. Conservation and Repair Works for Traditional Timber Mosque in Malaysia: A Review on Techniques. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 5, 663–668. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, K.S.; Ab Wahab, L.; Che Ahmad, A. Climatic Design of the Traditional Malay House to Meet the Requirements of Modern Living. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference of Architectural Science Association ANZAScA “Contexts of Architecture”, Launceston, Tasmania, 10–12 November 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, E.; Mursib, G.; Nafida, R.; Shahedi, B. Design Values in Traditional Architecture: Malay House. In Proceedings of the 6th International Seminar on Vernacular Settlements, Contemporary Vernaculars: Places, Processes, and Manifestations, Famagusta, North Cyprus, 19–21 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.R.; Ariffin, S.I.; Wang, M.H. The Typological Rule System of Malay Houses in Peninsula Malaysia. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2008, 7, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.-S. Timber Structures in Malaysian Architecture and Buildings. Ph.D Thesis, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia, 1995; pp. 1–281. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, M.H.; Ali, M.; Ismail, K.M.; Hashim, K.S.H.Y.; Suhaimi, M.S. Spatial Analysis on Malay Buildings for Categorization of Malay Historic BIM Library. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; Harun, S.N.; Mat, N. The Reinstallation and Conservation of Malay Traditional Buildings. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Architecture 2017, Banda Aceh, Indonesia, 18–19 October 2017; Volume 2017, pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shuaib, A.A.; Enoch, O.F. Integrating the Malay Traditional Design Elements into Contemporary Design: An Approach towards Sustainable Innovation. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 129, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samra, B. The Characteristics of Malay House Spatial Layout of Pekanbaru in Accordance with Islamic Values. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 97, 012049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M.H.; Ahmad, A.M.Z.; Latif, M.P.A.; Yunos, M.Y.M. Visual Communication of the Traditional House in Negeri Sembilan. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2018, 5, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nor Haniza, I.; Zuraini Md, A.; Yacob, O.; Helena Aman, H. Case Studies on Timber Defects of Selected Traditional Houses in Malacca. J. Des. Built Environ. 2007, 3, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kharade, A.S.; Kapadiya, S.V. The Impact Analysis of RC Structures under the Influence of Tsunami Generated Debris. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2013, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, S. Malaysia’s Floods of December 2021: Can Future Disasters Be Avoided? ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute: Heng Mui Keng Ter, Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bin Saedon, M. Tourists’ Perception on Virtual Reality Application of Traditional Malay House. Int. J. Creat. Multimed. 2022, 3, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idham, H.M.N.; Siti Suriawati, I. Preliminary Study of Malay Traditional Design Authenticity in Malaysian Tourist Accommodation Facilities. Adventure Ecotourism Malays. 2016, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Suaib, N.M.; Ismail, N.A.F.; Sadimon, S.; Yunos, Z.M. Cultural Heritage Preservation Efforts in Malaysia: A Survey. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 979, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.; Remøy, H. Heritage Building Preservation vs Sustainability? Conflict Isn’t Inevitable. Conversation 2017, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Feilden, B.M. Conservation of Historic Buildings, 3rd ed.; Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 2013206534. [Google Scholar]

- Elwazani, S. Attending to Engineering Heritage. In Proceedings of the 2003 Annual Conference, Nashville, Tennessee, 22–25 June 2003; pp. 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.F. Engineer’s Approach to Conservation. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Eng. Hist. Herit. 2017, 170, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvine Engineering What Is Historic Preservation Engineering? Available online: https://www.alvine.com/2020/03/27/what-is-historic-preservation-engineering/ (accessed on 20 January 2010).

- Kocabas, A. Sustainable Urban Conservation: A Multi-Dimensional Conceptual Framework. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development, Guimaraes, Portugal, 22–25 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Silman, R. Heritage Preservation Engineering Education at The National Level; University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS Principles for the Conservation of Wooden Built Heritage. In Proceedings of the 19th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium “Heritage and Democracy”, New Delhi, India, 11–15 December 2017.

- Terlikowski, W. Problems and Technical Issues in the Diagnosis, Conservation, and Rehabilitation of Structures of Historical Wooden Buildings with a Focus on Wooden Historic Buildings in Poland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.E.; Marstein, N. Conservation of Historic Timber Structures an Ecological Approach; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oslo, Norway, 2000; ISBN 978-0750634342. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, A.A.; Zulkifli, M.H. The Relocation, Conservation and Preservation of Kampung Teluk Memali Mosque in Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2018, 177, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M.S. Challenges in the Conservation of the Negeri Sembilan Traditional Malay House (NSTMH) and Establishment of a Conservation Principles Framework. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Percival, S. A Vibrant Tradition of Artistic Exchange. In 60 Years Australia in Malaysia 1955–2015; Good News Resources Sdn. Bhd.: Klang, Malaysia, 2015; p. 168. ISBN 9781743222782. [Google Scholar]

- Wan Hashimah, W.I. Preservation and Recycling of Heritage Buildings in Malacca. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 85, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.R. Reconstituted Village: Relocating Traditional Houses and Transforming Traditional Malay Villages. J. Reg. City Plan. 2019, 30, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.; Olanrewaju, A.; Lee, L.T. Maintenance of Heritage Building: A Case Study from Ipoh, Malaysia. MATEC Web Conf. 2016, 47, 04003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism Malaysia. Annual Report Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board; Tourism Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2019.

- Sodangi, M.; Khamidi, M.F.; Idrus, A. Towards Sustainable Heritage Building Conservation in Malaysia. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 1, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hasshim, S.A.; Rahman, A.A.; Khalid, M.M.; Samad, A.M. Service Quality Model towards Spatial Planning Analysis for Conservation of Malay Traditional House Landscape Characteristics. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering (ICCSCE), Penang, Malaysia, 27–29 November 2015; pp. 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Choi, B.K.; Lee, T.J. The Role and Dimensions of Authenticity in Heritage Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.A.; Hasshim, S.A.; Rozali, R. Residents’ Preference on Conservation of the Malay Traditional Village in Kampong Morten, Malacca. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 202, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrizaa, R.; Nurfaisal, B.; Kartina, A. The History And Transformation of Perak Malay Traditional House. Malays. J. Sustain. Environ. 2021, 8, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Said, S.; Embi, M.R. A Parametric Shape Grammar of the Traditional Malay Long-Roof Type Houses. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 2008, 6, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.S.A.; Baharuddin, M.N.; Alauddin, K.; Choo, I.A.H. Decorative Elements of Traditional Malay House: Comparative Study of Rumah Limas Bumbung Perak (RLBP) and Rumah Limas Johor (RLJ). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 385, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, F.b.A.; Shahminan, R.N.b.R.; Ibrahim, F.K.b. The Influences of the Architecture and Ornamentation in Melaka Traditional Houses: A Case Study of Rumah Demang Abdul Ghani, Merlimau, Melaka. J. Asian Sci. Res. 2015, 5, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.H.; Teh, H.H.W.; Yuan, L. Under One Roof: The Traditional Malay House. IDRC Rep. 1984, 2, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayahtuljamilah, N.; Ramli, B.; Kassim, N.; Zafrullah, M.; Mohd, H.; Masri, M.H.; Mara, U.T.; Alam, S.; Selangor, D.E.; Mara, U.T.; et al. Re-Adaptation of Malay Vernacular Architecture Thermal Comfort Elements: Towards Sustainable Design in Malaysia. (A Literature Review). In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Innovation and Technology for Sustainable Built Environment 2012 (ICITSBE 2012), Perak, Malaysia, 16–17 April 2012; pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kosman, K.A.; Haron, H.; Tazilan, A.S.M.; Yusof, N.A. The Typology of Mortises in the Traditional Malay House in Malaysia. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 977–985. [Google Scholar]

- Santana Quintero, M.; Blake, B.; Eppich, R. Heritage Documentation for Conservation: Partnership in Learning. In Proceedings of the 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Finding the Spirit of Place—Between the Tangible and the Intangible’, Quebec, QC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Wooden Architecture: Traditional Karelian Timber Architecture and Landscape. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/150907-preservation-of-karelias-wooden-buildings (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Carney, A.; Voigt, K. Preventive Preservation: The Importance of Environmental Monitoring and Integrated Pest Management in Maintaining Library Collections. Available online: https://publish.illinois.edu/conservationlab/2020/04/28/preventive-preservation-the-importance-of-environmental-monitoring-and-integrated-pest-management-in-maintaining-library-collections/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Čebron, L.; Van, B.K. Preventive Conservation and Maintenance of Architectural Heritage as Means of Preservation of the Spirit of Place. In Proceedings of the 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Finding the Spirit of Place—Between the Tangible and the Intangible’, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kayan, B.A. University-Community Engagement Programme: A Case Study of Traditional Melakan House Inspection in Malacca Historical City, Malaysia. Australas. J. Univ. Engagem. 2015, 10, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Curcic, A.; Momcilovic-Petronijevic, A.; Toplicic-Curcic, G.; Kekovic, A. An Approach to Building Heritage and Its Preservation in Serbia and Surrounding Areas. Facta Univ.-Ser. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2020, 18, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage Care. General Methodology for the Preventive Conservation of Cultural Heritage Buildings; Interreg Sudoe: Toulouse, France, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Z.; Harun, S.N. Preservation of Malay Singgora Roof. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2013, 17, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latip, N.A.; Umar, M.U.; Noriman, N.Z.; Johari, I.; Dahham, O.S.; Hamzah, R.; Ruhaiyem, N.I.R. Identification of Timber Material Defect Using VIA on Selected Traditional Malay House: Case Study on Tuan Hj Hashim Itam (Kerani) Historical House at Penang, Malaysia. AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2213, 020281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, H.; Yeomans, D.; Tsakanika, E.; Macchioni, N.; Jorissen, A.; Touza, M.; Mannucci, M.; Lourenço, P.B. Guidelines for On-Site Assessment of Historic Timber Structures. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2015, 9, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikonova, A.A.; Biryukova, M.V. The Role of Digital Technologies in the Preservation of Cultural Heritage. Muzeol. Kult. Dedicstvo 2017, 5, 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P. How Is 3D Laser Scanning Helping Effective Heritage Documentation? Available online: https://www.novatr.com/blog/3d-laser-scanning-for-heritage-documentation#:~:text=Photogrammetry%20utilizes%20a%20method%20of,structure%20in%20a%20virtual%20environment (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Precision Surveying & Consulting How 3D Scanning Transforms Historic Preservation. Available online: https://precisionsurveyingandconsulting.com/how-3d-scanning-transforms-historic-preservation/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- BIMPACT Designs The Role of BIM in Historical Preservation and Restoration Projects. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/role-bim-historical-preservation-restoration-projects (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Nazrita, I.; Khairul Azhar, A. Preserving Malay Architectural Heritage through Virtual Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHeritage), Marseille, France, 28 October–1 November 2013; Volume 1, pp. 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, N.Z.; Yanti Mahadzir, S. 360° Virtual Tour of the Traditional Malay House as an Effort for Cultural Heritage Preservation. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 764, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, A.; Hosamo, H.; Plevris, V.; Kioumarsi, M. A Preliminary Structural Survey of Heritage Timber Log Houses in Tonsberg, Norway. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Structural Analysis of Historical Constructions (SAHC), Online, 29 September–1 October 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, M.A.; Akasah, Z.A.; Abdullah, M.S.; Musa, M.K. Issues and Problems Affecting the Implimentation and Effectiveness of Heritage Buildings Maintenance. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/12007494.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Drougkas, A.; Verstrynge, E. Structural Conservation Engineering in Practice: Lessons Learned. In Professionalism in the Built Heritage Sector; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, N.Z.; Mohd Ariffin, N.A.; Abdullah, F. Changes and Threats in the Preservation of the Traditional Malay Landscape. J. Malays. Inst. Plan. 2017, 15, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shabani, A.; Kioumarsi, M.; Plevris, V.; Stamatopoulos, H. Structural Vulnerability Assessment of Heritage Timber Buildings: A Methodological Proposal. Forests 2020, 11, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Climate Risk Country Profile—Malaysia; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WBDG Historic Preservation. Available online: https://www.wbdg.org/design-objectives/historic-preservation (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Rani, W.N.M.W.M.; Tamjes, M.S.; Wahab, M.H. Governance of Heritage Conservation: Overview on Malaysian Practice. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 2018, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduardo, R. Sustainable Preservation of the Urban Heritage Lessons from Latin America. GCI Newsl. 2011, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Ramli, N.H. Re-Adaptation of Malay House Thermal Comfort Design Elements into Modern Building Elements—Case Study of Selangor Traditional Malay House & Low Energy Building in Malaysia. Iran. J. Energy Environ. 2012, 3, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).