Use of Social Media in Disaster Management: Challenges and Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

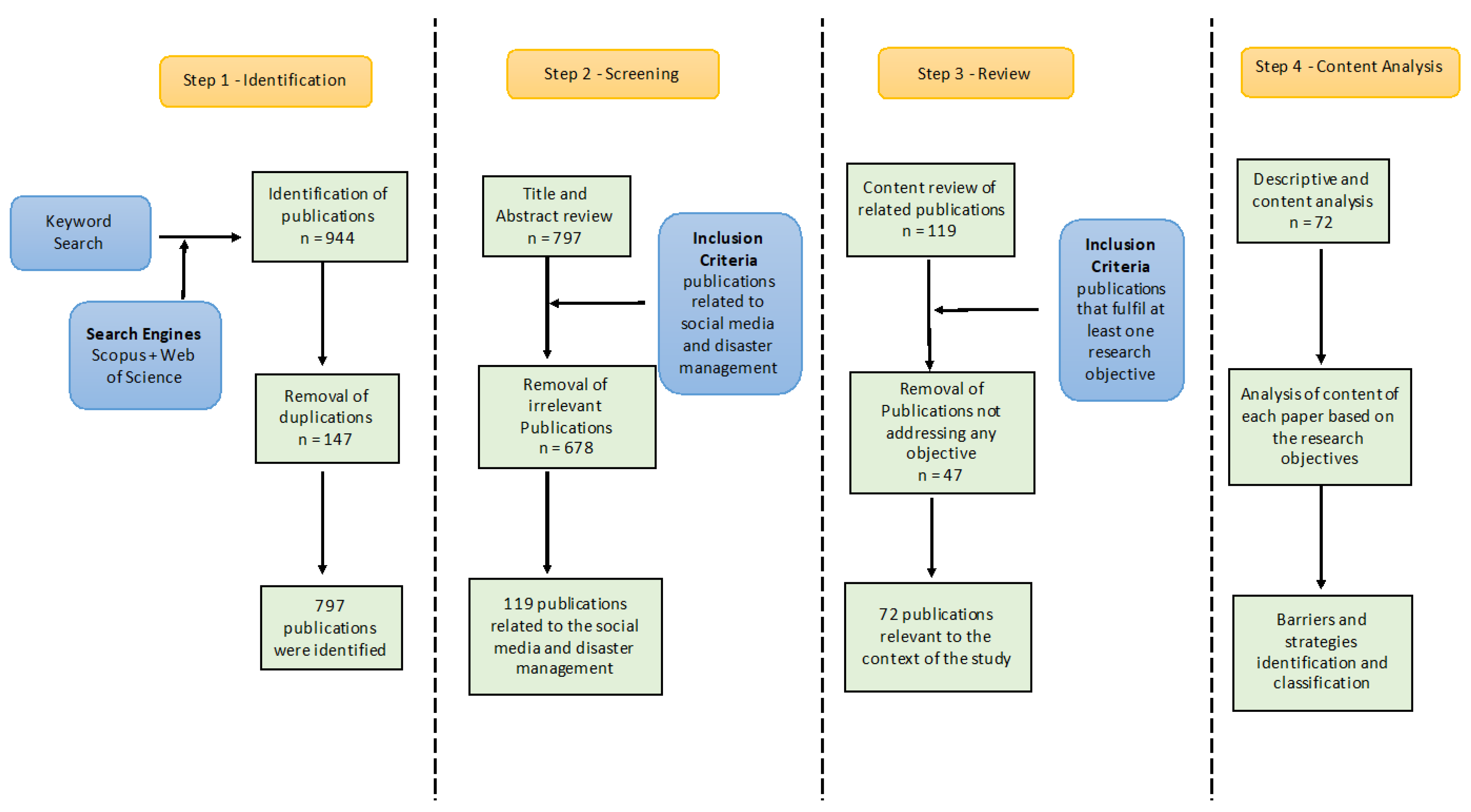

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of Papers

2.2. Descriptive and Content Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis of the Publications

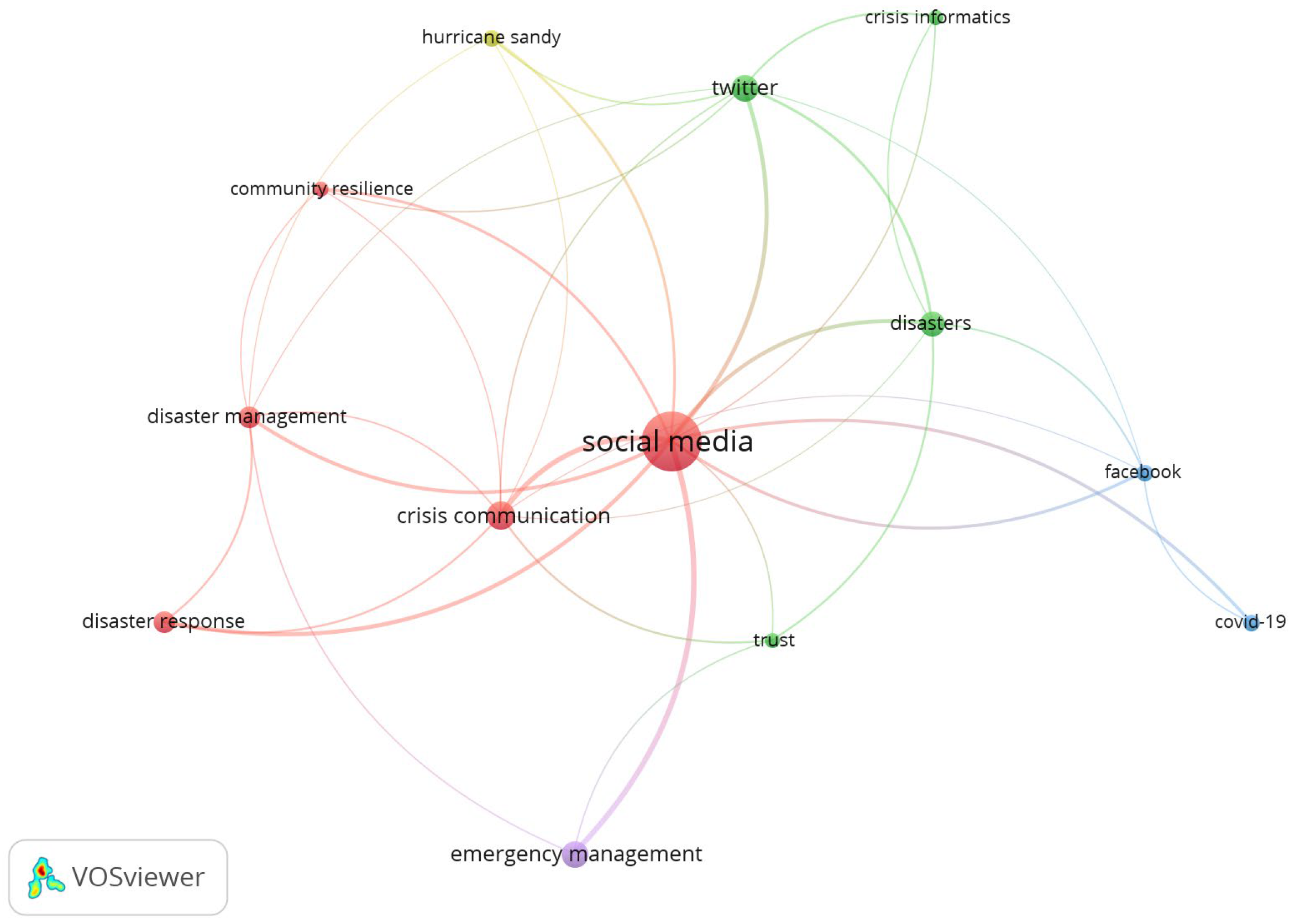

3.1.1. Co-Occurrence Network of Keywords

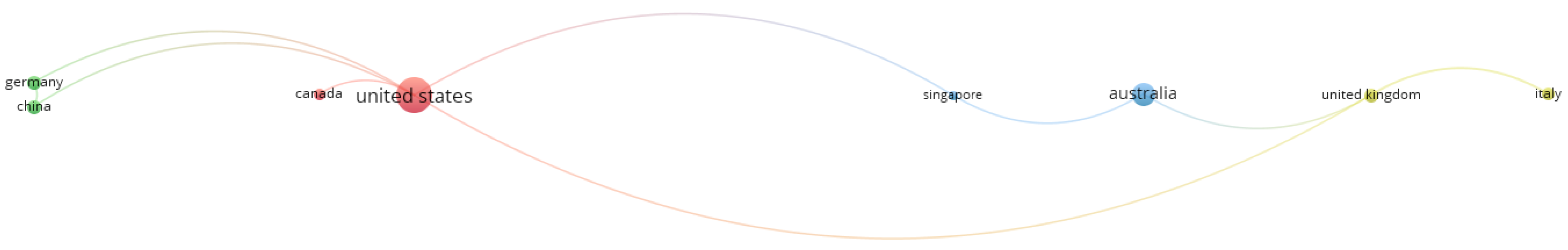

3.1.2. Collaboration Network of Countries

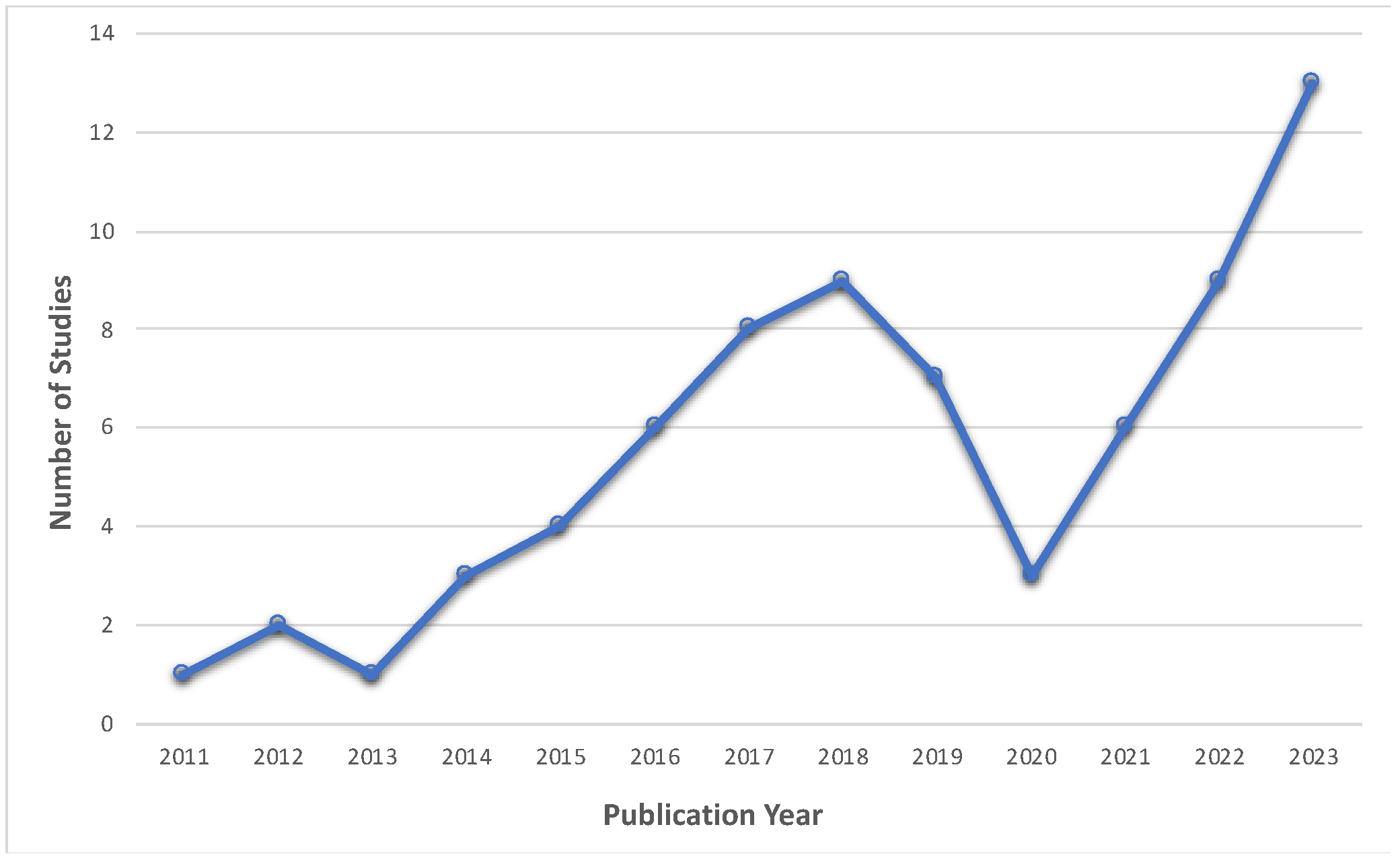

3.1.3. Annual Trend of Publications

3.2. A Content Analysis of the Publications

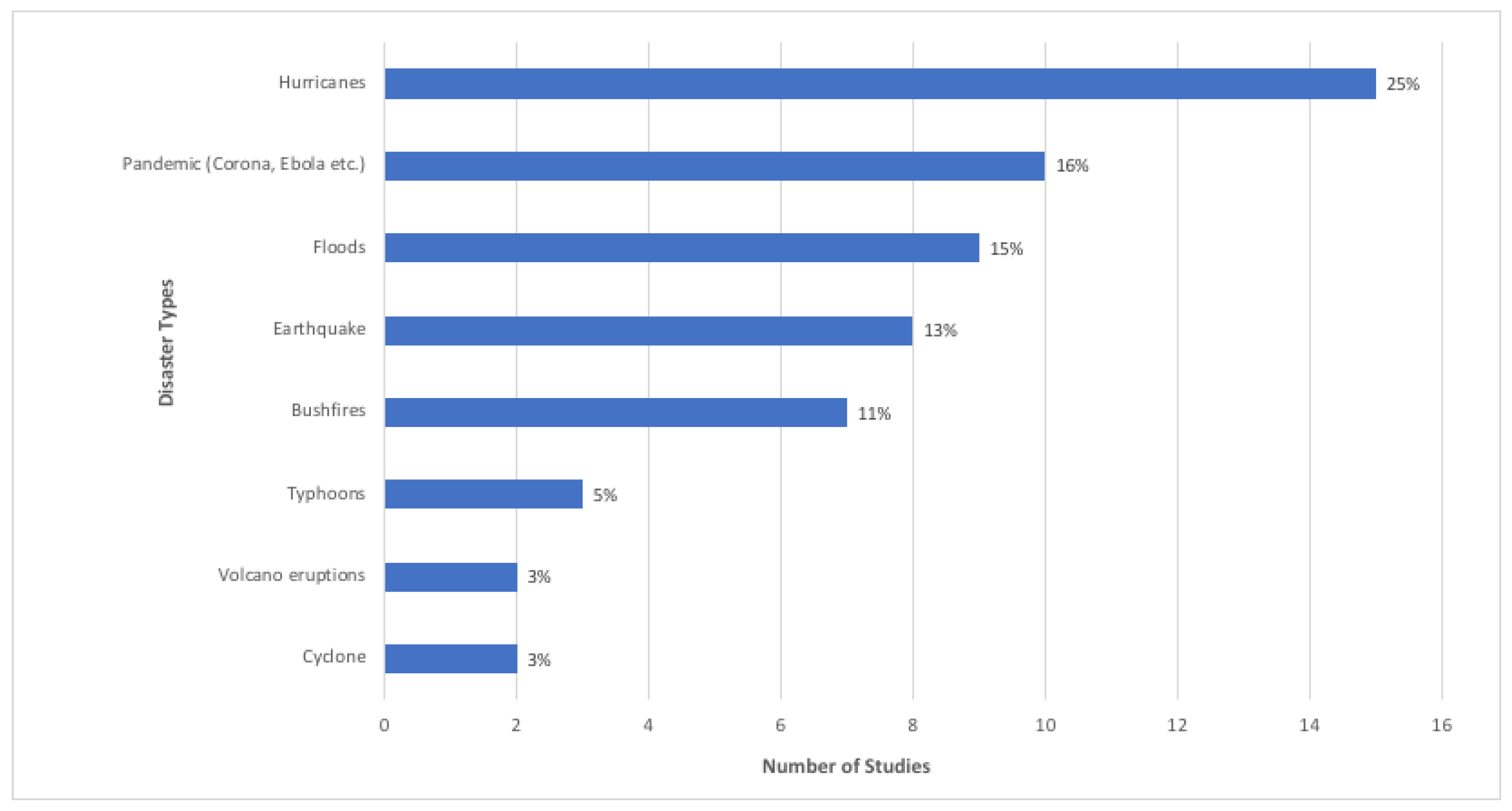

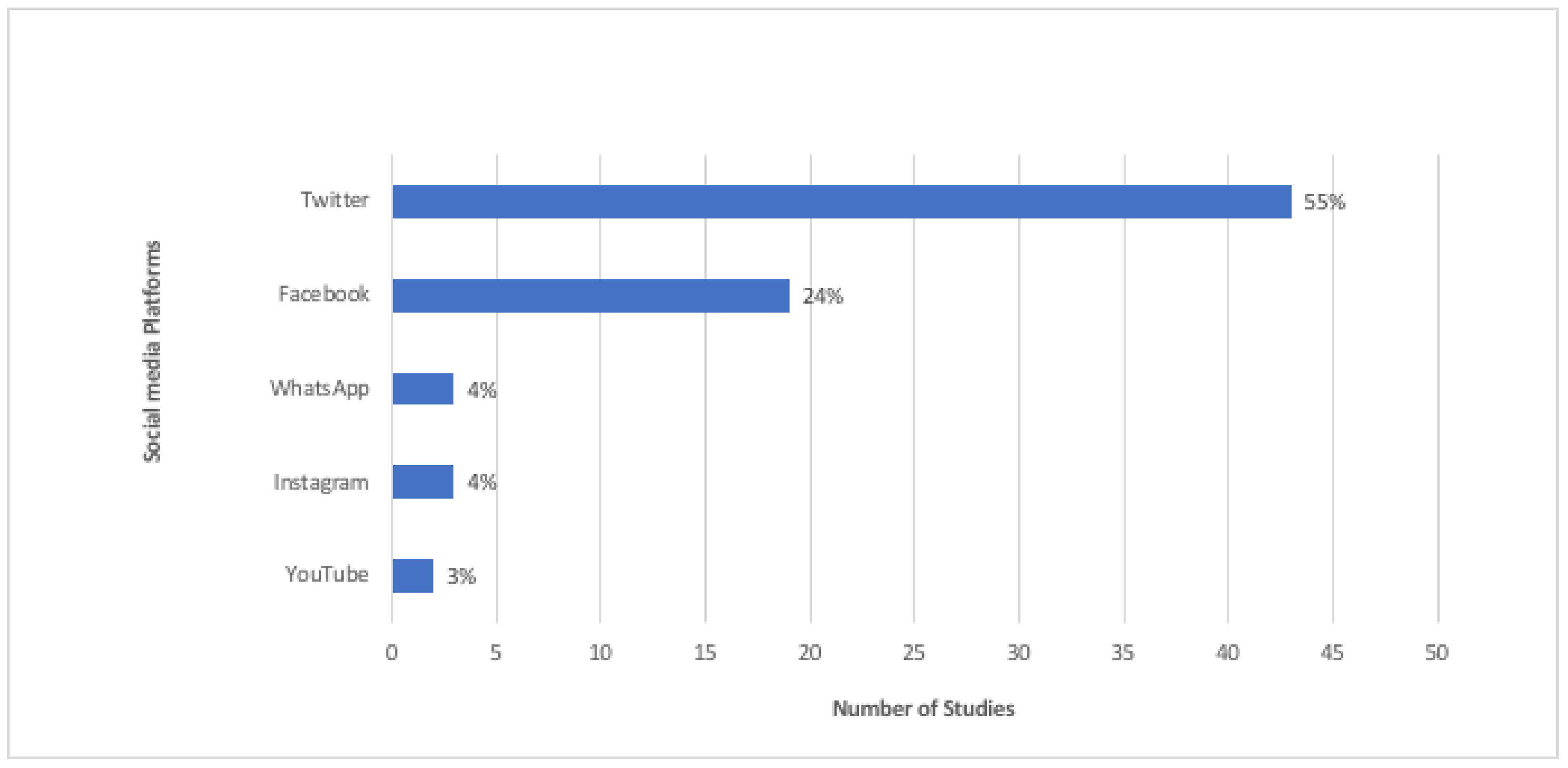

3.2.1. Social Media Platforms and Disaster Types

3.2.2. Challenges to the Use of SM in DM

Data-Related Challenges

Social Challenges

Technology-Related Challenges

Legal Challenges

3.2.3. Strategies to Overcome the Challenges for Using SM in DM

Organisations

Individuals

Social Media Companies

3.2.4. Conceptual Model

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ogie, R.I.; Clarke, R.J.; Forehead, H.; Perez, P. Crowdsourced social media data for disaster management: Lessons from the PetaJakarta.org project. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2019, 73, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vision of Humanity. Increase in Natural Disasters on a Global Scale by Ten Times. Available online: https://www.visionofhumanity.org/global-number-of-natural-disasters-increases-ten-times/ (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- The Emergency Events Database; Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED); Universit’e Catholique de Louvain (UCL): Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- Ogie, R.I.; James, S.; Moore, A.; Dilworth, T.; Amirghasemi, M.; Whittaker, J. Social media use in disaster recovery: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 70, 102783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acikara, T.; Xia, B.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Hon, C. Contribution of Social Media Analytics to Disaster Response Effectiveness: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, M.; Nejat, A.; Ghosh, S.; Jin, F.; Cao, G. Social media data and post-disaster recovery. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Regona, M.; Kankanamge, N.; Mehmood, R.; D’Costa, J.; Lindsay, S.; Nelson, S.; Brhane, A. Detecting Natural Hazard-Related Disaster Impacts with Social Media Analytics: The Case of Australian States and Territories. Sustainability 2022, 14, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukkamala, A.; Beck, R. Social media for disaster situations: Methods, opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the GHTC 2017—IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference, Proceedings, San Jose, CA, USA, 19–22 October 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, V.; Nikolić, A.; Ivanov, A. The Role of Social Media in the Process of Informing the Public About Disaster Risks. J. Lib. Int. Aff. 2023, 9, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarreño-Aramendia, G.; Cristòfol, F.J.; de-San-Eugenio-Vela, J.; Ginesta, X. Social-Media Analysis for Disaster Prevention: Forest Fire in Artenara and Valleseco, Canary Islands. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, N.S.N.; Meyer, M.; Reams, M.; Yang, S.; Lee, K.; Zou, L.; Mihunov, V.; Wang, K.; Kirby, R.; Cai, H. Improving social media use for disaster resilience: Challenges and strategies. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 3023–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, T.; Ngamassi, L.; Rahman, S. Examining the Factors that Influence the Use of Social Media for Disaster Management by Underserved Communities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2022, 13, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wu, K. Understanding social media data for disaster management. Nat. Hazards 2015, 79, 1663–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, J.A. Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics 2006, 34, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, R.T.; McPhearson, T. Social-media data for urban sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, A.; Agrawal, R. Social media and disaster management: Investigating challenges and enablers. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2022, 73, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Mengersen, K.; Bennett, S.; Mazerolle, L. Viewing systematic reviews and meta-analysis in social research through different lenses. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wafa, W.; Sharaai, A.H.; Matthew, N.K.; Ho, S.A.J.; Akhundzada, N.A. Organizational Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (OLCSA) for a Higher Education Institution as an Organization: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, C.; Franchi, T.; Mathew, G.; Kerwan, A.; Nicola, M.; Griffin, M.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. PRISMA 2020 statement: What’s new and the importance of reporting guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zuo, J.; Wu, G.; Huang, C. A bibliometric review of green building research 2000–2016. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2019, 62, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz-Rodriguez, K.; Ofori, S.K.; Bayliss, L.C.; Schwind, J.S.; Diallo, K.; Liu, M.; Yin, J.; Chowell, G.; Fung, I.C. Social Media Use in Emergency Response to Natural Disasters: A Systematic Review With a Public Health Perspective. Disaster Med. Public. Health Prep. 2020, 14, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Fan, C.; Yao, W.; Hu, X.; Mostafavi, A. Social media for intelligent public information and warning in disasters: An interdisciplinary review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A. Social media in disaster management: Review of the literature and future trends through bibliometric analysis. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 953–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, H.; Cruz-Antonio, O.; Quintero-Perez, D.; Garcia, S.D.; Davidson, R.; Kendra, J.; Starbird, K. Searching for signal and borrowing wi-fi: Understanding disaster-related adaptations to telecommunications disruptions through social media. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 86, 103548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Liao, D.; Lam, N.S.N.; Meyer, M.A.; Gharaibeh, N.G.; Cai, H.; Zhou, B.; Li, D. Social media for emergency rescue: An analysis of rescue requests on Twitter during Hurricane Harvey. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 85, 103513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.K.; Sibarani, R.; Lassa, J.; Nguyen, D.; Dimmock, A. How do Australians use social media during natural hazards? A survey. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 81, 103207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonati, S.; Nardini, O.; Boersma, K.; Clark, N. Unravelling dynamics of vulnerability and social media use on displaced minors in the aftermath of Italian earthquakes. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 89, 103632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anson, S.; Watson, H.; Wadhwa, K.; Metz, K. Analysing social media data for disaster preparedness: Understanding the opportunities and barriers faced by humanitarian actors. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 21, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, S. New tools for emergency managers: An assessment of obstacles to use and implementation. Disasters 2016, 40, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, A.M.; Bruns, A.; Newton, J. Trust, but verify: Social media models for disaster management. Disasters 2017, 41, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; An, S.; Kapucu, N.; Sellnow, T.L.; Yuksel, M.; Freihaut, R. Dynamics of Interorganizational Emergency Communication on Twitter: The Case of Hurricane Irma. Disasters 2023, 47, 267–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stovall, W.K.; Ball, J.L.; Westby, E.G.; Poland, M.P.; Wilkins, A.; Mulliken, K.M. Officially social: Developing a social media crisis communication strategy for USGS Volcanoes during the 2018 Kīlauea eruption. Front. Commun. 2023, 8, 976041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabong, P.T.N.; Segtub, M. Misconceptions, Misinformation and Politics of COVID-19 on Social Media: A Multi-Level Analysis in Ghana. Front. Commun. 2021, 6, 613794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D.; Irons, M. Communication, Sense of Community, and Disaster Recovery: A Facebook Case Study. Front. Commun. 2016, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, A.; Bunker, D.; Levine, L.; Sleigh, A. Emergency management in the changing world of social media: Framing the research agenda with the stakeholders through engaged scholarship. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.C.; Hasan, S.; Sadri, A.M.; Cebrian, M. Understanding the efficiency of social media based crisis communication during hurricane Sandy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hastak, M. Social network analysis: Characteristics of online social networks after a disaster. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 38, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Pinto, J.; Zhong, B. Building community resilience on social media to help recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 134, 107294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, H.; Platt, L.S. Examining risk and crisis communications of government agencies and stakeholders during early-stages of COVID-19 on Twitter. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keim, M.E.; Noji, E. Emergent use of social media: A new age of opportunity for disaster resilience. Am. J. Disaster Med. 2011, 6, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, L.; Lam, N.S.N.; Cai, H.; Qiang, Y. Mining Twitter Data for Improved Understanding of Disaster Resilience. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2018, 108, 1422–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.H.C.; Zhou, C.T. Practice Update—Social-psychological emergency response during Wuhan lockdown: Internet-based crisis intervention. Australas. J. Disaster Traum. Stud. 2022, 26, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, V.; Hayes, P.; Karanasios, S. Building Social Resilience and Inclusion in Disasters: A Survey of Vulnerable Persons’ Social Media Use. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2022, 26, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufty, N. Using social media to build community disaster resilience. Aus. J. Emerg. Manage. 2012, 27, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, J.D.; Capello, H.T. Spatial patterns and demographic indicators of effective social media content during the horsethief canyon fire of 2012. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 40, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, A.H.; Moore, K. Good Enough is Good Enough: Overcoming Disaster Response Organizations’ Slow Social Media Data Adoption. Comput. Support. Coop. Work. CSCW Int. J. 2014, 23, 483–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliacozzo, S.; Magni, M. Government to Citizens (G2C) communication and use of social media in the post-disaster reconstruction phase. Environ. Hazards 2018, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todesco, M.; De Lucia, M.; Bagnato, E.; Behncke, B.; Bonforte, A.; De Astis, G.; Giammanco, S.; Grassa, F.; Neri, M.; Scarlato, P.; et al. Eruptions and Social Media: Communication and Public Outreach About Volcanoes and Volcanic Activity in Italy. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 926155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Johnson, P. Challenges in the adoption of crisis crowdsourcing and social media in Canadian emergency management. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusna, N.I.; Bachri, S.; Astina, I.K.; Susilo, S. Social resilience and disaster resilience: A strategy in disaster management efforts based on big data analysis in Indonesian’s twitter users. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, N.R.; Shafiq, B.; Staffin, R. Spatial computing and social media in the context of disaster management. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2012, 27, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poblete, B.; Guzman, J.; Maldonado, J.; Tobar, F. Robust Detection of Extreme Events Using Twitter: Worldwide Earthquake Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2018, 20, 2551–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, A.; Matthews, L. The use of Facebook for information seeking, decision support, and self-organization following a significant disaster. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 1680–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedin, B.; Babar, A. Institutional vs. Non-institutional use of Social Media during Emergency Response: A Case of Twitter in 2014 Australian Bush Fire. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Yoo, E.; Yan, L.; Pedraza-Martinez, A. Speak with One Voice? Examining Content Coordination and Social Media Engagement During Disasters. Inf. Syst. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauroner, O.; Heudorfer, A. Social media in disaster management: How social media impact the work of volunteer groups and aid organisations in disaster preparation and response. Int. J. Emerg. Manag. 2016, 12, 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Jung, K.; Chilton, K. Strategies of social media use in disaster management: Lessons in resilience from Seoul, South Korea. Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2016, 5, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laylavi, F.; Rajabifard, A.; Kalantari, M. A multi-element approach to location inference of Twitter: A case for emergency response. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldeniya, D.; De Choudhury, M.; Garcia, D.; Romero, D.M. Pulling through together: Social media response trajectories in disaster-stricken communities. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 2023, 6, 655–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Jiang, Y.; Mostafavi, A. The Role of Local Influential Users in Spread of Situational Crisis Information. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2021, 26, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Hanashima, M.; Sano, H.; Ikeda, M.; Handa, N.; Taguchi, H.; Usuda, Y. An attempt to grasp the disaster situation of “the 2018 Hokkaido eastern iburi earthquake” using SNS information. J. Disaster Res. 2019, 14, 1170–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; He, W.; He, Y.; Albert, S.; Howard, M. Using health belief model and social media analytics to develop insights from hospital-generated twitter messaging and community responses on the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2023, 36, 1483–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurman, T.A.; Ellenberger, N. Reaching the global community during disasters: Findings from a content analysis of the organizational use of twitter after the 2010 haiti earthquake. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bec, A.; Becken, S. Risk perceptions and emotional stability in response to Cyclone Debbie: An analysis of Twitter data. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 721–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, M.; Bunker, D.; Sorrell, T.C. Communicating shared situational awareness in times of chaos: Social media and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Assoc. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 74, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C.; Pan, S.L.; Ractham, P.; Kaewkitipong, L. ICT-enabled community empowerment in crisis response: Social media in Thailand flooding 2011. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 16, 174–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, G.G.; Kurniadi, D.; Nurliawati, N. Content Analysis of Social Media: Public and Government Response to COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia. J. Ilmu Sos. Ilmu Polit. 2021, 25, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliacozzo, S.; Magni, M. Communicating with communities (CwC) during post-disaster reconstruction: An initial analysis. Nat. Hazards 2016, 84, 2225–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E.; Takahashi, B. Log in if you survived: Collective coping on social media in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. New Media Soc. 2016, 19, 1778–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Deng, Y.; Yang, W.; Li, B. “help! Can You Hear Me?”: Understanding How Help-Seeking Posts are Overwhelmed on Social Media during a Natural Disaster. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2022, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lai, C.-H.; Xu, W. Tweeting about emergency: A semantic network analysis of government organizations’ social media messaging during Hurricane Harvey. Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wukich, C. Preparing for Disaster: Social Media Use for Household, Organizational, and Community Preparedness. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2019, 10, 233–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, L.; Keller, T.; Neely, S.; DePaula, N.; Robert-Cooperman, C. Crisis Communications in the Age of Social Media: A Network Analysis of Zika-Related Tweets. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2018, 36, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Haunert, J.H.; Knechtel, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, Q.; Dehbi, Y. Social media insights on public perception and sentiment during and after disasters: The European floods in 2021 as a case study. Trans. GIS 2023, 27, 1766–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momin, K.; Kays, H.M.I.; Sadri, A.M. Identifying Crisis Response Communities in Online Social Networks for Compound Disasters: The Case of Hurricane Laura and COVID-19. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2210.14970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.T.; Mueller, J.L.; Jones, M.L. Use of social media during public emergencies by people with disabilities. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2014, 15, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velivela, V.; Raj, C.; Tiwana, M.S.; Prasanna, R.; Samarawickrama, M.; Prasad, M. The Effectiveness of Social Media Engagement Strategy on Disaster Fundraising. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2210.11322. [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk, H.; Starbird, K. Analyzing social media data to understand how disaster-affected individuals adapt to disaster-related telecommunications disruptions. In Proceedings of the International ISCRAM Conference, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 24–27 May 2020; pp. 704–717. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufhold, M.A.; Reuter, C. The impact of social media for emergency services: A case study with the fire department Frankfurt. In Proceedings of the International ISCRAM Conference, Méditerranée, France, 21–24 May 2019; pp. 603–612. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, S.; Thompson, C.; Graham, C. Getting disaster data right: A call for real-time research in disaster response. In Proceedings of the International ISCRAM Conference, Rochester, NY, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 841–850. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, R.; Kropczynski, J.; Tapia, A. Community coordination: Aligning social media use in community emergency management. In Proceedings of the International ISCRAM Conference, Rochester, NY, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 609–620. [Google Scholar]

- Nagahawatta, R.; Kaluarachchi, C.; Warren, M.; Sedera, D. Strategic Use of Social Media in COVID-19 Pandemic. Pandemic Management by Sri Lankan Leaders and Health Organisations Using the CERC Model. In Proceedings of the ACIS 2022—Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Proceedings, Melbourne, Australia, 4–7 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.; Jiang, Y.; Mostafavi, A. Seeding Strategies in Online Social Networks for Improving Information Dissemination of Built Environment Disruptions in Disasters. In Proceedings of the Computing in Civil Engineering 2019: Data, Sensing, and Analytics—Selected Papers from the ASCE International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering 2019, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–19 June 2019; pp. 487–494. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, C.; Ludwig, T.; Kaufhold, M.A.; Pipek, V. XHELP: Design of a cross-platform social-media application to support volunteermoderators in disasters. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems—Proceedings, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 4093–4102. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Sadri, A.M.; Pradhananga, P.; Elzomor, M.; Pradhananga, N. Social Media Communication Patterns of Construction Industry in Major Disasters. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2020: Computer Applications—Selected Papers from the Construction Research Congress 2020, Tempe, AZ, USA, 8–10 March 2020; pp. 678–687. [Google Scholar]

- Salsabilla, F.P.; Hizbaron, D.R. Understanding Community Collective Behaviour Through Social Media Responses: Case of Sunda Strait Tsunami, 2018, Indonesia. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Ulis, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Purohit, H.; Bhatt, S.; Hampton, A.; Shalin, V.; Sheth, A.; Flach, J. With whom to coordinate, why and how in ad-hoc social media communities during crisis response. In Proceedings of the ISCRAM 2014 Conference Proceedings—11th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, University Park, PA, USA, 18-21 May 2014; pp. 787–791. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Drake, W.; Li, Y.; Zobel, C.; Cowell, M. Fostering community resilience through adaptive learning in a social media age: Municipal twitter use in New Jersey following Hurricane Sandy. In Proceedings of the ISCRAM 2015 Conference Proceedings—12th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, Tarbes, France, 22–25 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jayathilaka, H.A.D.G.S.; Siriwardana, C.S.A.; Amaratunga, D.; Haigh, R.P.; Dias, N. Investigating the Variables that Influence the Use of Social Media for Disaster Risk Communication in Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Sustainable Built Environment 2020: The Kandy Conference, Kandy, Sri Lanka, 10–12 December 2020; pp. 259–276. [Google Scholar]

- Nalluru, G.; Pandey, R.; Purohit, H. Relevancy classification of multimodal social media streams for emergency services. In Proceedings of the Proceedings—2019 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing, SMARTCOMP 2019, Washington, DC, USA, 12–15 June 2019; pp. 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.S. Explicit disaster response features in social media: Safety check and community help usage on facebook during typhoon Mangkhut. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, MobileHCI 2019, Taipei, Taiwan, 1–4 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tha, K.K.O.; Pan, S.L.; Sandeep, L.M.S. Exploring Social media affordances in natural disaster: Case study of 2015 myanmar flood. In Proceedings of the 28th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, ACIS 2017, Hobart, Australia, 4–6 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dailey, D.; Starbird, K. Social media seamsters: Stitching platforms & audiences into local crisis infrastructure. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW, Portland, OR, USA, 25 February–1 March 2017; pp. 1277–1289. [Google Scholar]

- De-Graft, J.O.; Perera, S.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Rashidi, M.; Bamdad, K.; Famakinwa, T. Barriers to the Adoption of Digital Twin in the Construction Industry: A Literature Review. Informatics 2023, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, N.; Haleem, A. Exploring the Nexus of Eco-Innovation and Sustainable Development: A Bibliometric Review and Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibanez Gonzalez, E.D.R.; Kandpal, V.; Machado, M.; Martens, M.L.; Majumdar, S. A Bibliometric Analysis of Circular Economies through Sustainable Smart Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdman, J. The 10 Most Unforgettable Weather Disasters of the 2010s. Available online: https://weather.com/news/news/2019-12-04-10-biggest-us-weather-stories-of-the-decade (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- Gissing, A.; Timms, M.; Browning, S.; Crompton, R.; McAneney, J. Compound natural disasters in Australia: A historical analysis. Environ. Hazards 2022, 21, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Disaster Resilience. Australian Disasters. Available online: https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/collections/australian-disasters/ (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- Khan, S.A.; Shahzad, K.; Shabbir, O.; Iqbal, A. Developing a Framework for Fake News Diffusion Control (FNDC) on Digital Media (DM): A Systematic Review 2010–2022. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimiziarani, M. Social Media Analytics in Disaster Response: A Comprehensive Review. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2307.04046. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi Asr, F.; Taboada, M. Big Data and quality data for fake news and misinformation detection. Big Data Soc. 2019, 6, 2053951719843310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Jiang, H.; Shen, H.; Shi, L.; Cheng, N. Sustainable Development of Information Dissemination: A Review of Current Fake News Detection Research and Practice. Systems 2023, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M.A.; Vilares, D.; Gómez-Rodríguez, C.; Vilares, J. Sentiment Analysis for Fake News Detection. Electronics 2021, 10, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Source (Journal/Conference) | No of Publications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| JP | Journal Papers | 54 | [11,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] |

| CP | Conference Papers | 18 | [8,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94] |

| Total | 72 |

| Country | Papers | Citations | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 37 | 1848 | 5 |

| Australia | 14 | 652 | 2 |

| United Kingdom | 5 | 165 | 4 |

| Germany | 5 | 150 | 2 |

| China | 5 | 30 | 2 |

| Italy | 4 | 40 | 2 |

| Canada | 3 | 186 | 1 |

| Indonesia | 3 | 6 | 0 |

| Singapore | 2 | 183 | 2 |

| Number | Challenges | Sum | Rank | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spread of misinformation and disinformation | 10 | 1st | [8,27,33,34,38,41,57,75,81,83] |

| 2 | Insufficient human resources to manage social media use | 9 | 2nd | [11,29,30,48,50,80,81,82,89] |

| 3 | Lack of trust in information and authorities | 8 | 3rd | [31,44,45,47,48,69,82,92] |

| 4 | Poor information quality and content of message | 8 | 3rd | [26,30,33,36,59,66,75,77] |

| 5 | Difficulties in information accuracy and verification | 6 | 4th | [11,30,47,49,59,81] |

| 6 | Difficulties in data processing and analysis | 6 | 4th | [8,38,48,80,81,82] |

| 7 | Problems with internet connectivity during emergencies | 5 | 5th | [11,27,28,49,59] |

| 8 | Policy breaches and privacy violation issues | 5 | 5th | [33,38,48,50,52] |

| 9 | Language barriers | 3 | 6th | [11,27,29] |

| 10 | Low level of credibility of data | 3 | 6th | [30,50,54] |

| 11 | Disparities in social media use across different social groups | 3 | 6th | [26,28,43] |

| 12 | Miscommunication between victims and responders | 2 | 7th | [26,33] |

| 13 | Difficulties in learning social media platforms | 2 | 7th | [11,90] |

| 14 | Different levels of community expectations | 2 | 7th | [36,44] |

| 15 | Digital divide | 2 | 7th | [50,77] |

| 16 | Lack of data ownership | 1 | 8th | [11] |

| 17 | Difficulties in identifying and clearing bottlenecks | 1 | 8th | [33] |

| 18 | Resistant to change by authorities | 1 | 8th | [30] |

| Category | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Data | Poor information quality and content of message |

| Difficulties in information accuracy and verification | |

| Difficulties in data processing and analysis | |

| Lack of data ownership | |

| Low level of credibility of data | |

| Social | Insufficient human resources to manage social media use |

| Spread of misinformation and disinformation | |

| Lack of trust in information and authorities | |

| Different levels of community expectations | |

| Disparities in social media use across different social groups | |

| Resistant to change by organisations | |

| Language barriers | |

| Miscommunication between victims and responders | |

| Difficulties in learning social media platforms | |

| Technology | Problems with internet connectivity during emergencies |

| Digital divide | |

| Difficulties in identifying and clearing bottlenecks | |

| Legal | Policy breaches and privacy violation issues |

| Number | Strategies | Sum | Rank | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Comprehensive policy development to enable the secure use of social media | 3 | 1st | [30,50,89] |

| 2 | Adopting social media use guidelines | 2 | 2nd | [11,29] |

| 3 | Integrating social media with incident management systems | 2 | 2nd | [11,82] |

| 4 | Partnerships and alliances to adopt social media for emergency management | 2 | 2nd | [29,50] |

| 5 | Development of methods to verify of social media information | 2 | 2nd | [31,47] |

| 6 | Proactive engagement with the community using social media | 1 | 3rd | [11] |

| 7 | Raising awareness of official accounts | 1 | 3rd | [11] |

| 8 | Implementing rapid and automated data mining and visualisation tools in SM | 1 | 3rd | [26] |

| 9 | Delivering consistent, factual, and official information | 1 | 3rd | [33] |

| 10 | Open and honest communication | 1 | 3rd | [33] |

| 11 | Revolutionising crisis intervention skills for digital environments | 1 | 3rd | [43] |

| 12 | Management of myths and misinformation in social media | 1 | 3rd | [34] |

| 13 | Protecting the data privacy of individuals/victims | 1 | 3rd | [52] |

| 14 | Use of a social media plan for critical response phase | 1 | 3rd | [54] |

| 15 | Strategic use of social media features | 1 | 3rd | [11] |

| Category | Strategies |

|---|---|

| Organisations | Comprehensive policy development to enable the secure use of social media |

| Adopting social media use guidelines | |

| Integrating social media with incident management systems | |

| Partnerships and alliances to adopt social media for emergency management | |

| Proactive engagement with the community using social media | |

| Raising awareness of official accounts | |

| Delivering consistent, factual, and official information | |

| Open and honest communication | |

| Revolutionising crisis intervention skills for digital environments | |

| Use of a social media plan for critical response phase | |

| Individuals | Strategic use of social media features |

| SM companies | Development of methods to verify SM information |

| Implementing rapid and automated data mining and visualisation tools in SM | |

| Management of myths and misinformation in social media | |

| Protecting the data privacy of individuals/victims |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seneviratne, K.; Nadeeshani, M.; Senaratne, S.; Perera, S. Use of Social Media in Disaster Management: Challenges and Strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4824. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114824

Seneviratne K, Nadeeshani M, Senaratne S, Perera S. Use of Social Media in Disaster Management: Challenges and Strategies. Sustainability. 2024; 16(11):4824. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114824

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeneviratne, Krisanthi, Malka Nadeeshani, Sepani Senaratne, and Srinath Perera. 2024. "Use of Social Media in Disaster Management: Challenges and Strategies" Sustainability 16, no. 11: 4824. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114824

APA StyleSeneviratne, K., Nadeeshani, M., Senaratne, S., & Perera, S. (2024). Use of Social Media in Disaster Management: Challenges and Strategies. Sustainability, 16(11), 4824. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114824