Abstract

Informal settlements pose multifaceted challenges to urban development, necessitating a reconsideration of traditional upgrading approaches. This study examines the integration of the street-led approach within the Ezbit Hegazi informal settlement, leveraging the Alexandria University Centre of Excellence for Smart Urban Governance’s (ALEXU-CoE-SUG’s) innovative framework. It highlights the centrality of ‘Demand for Good Governance’ (DFGG) practices in bridging the gap between governmental (supply-side) and community (demand-side) objectives, fostering a collaborative urban upgrading process. Through an in-depth case study analysis, this paper reveals the potential of aligning governmental agendas with local aspirations, emphasizing the importance of local dynamics in sustainable urban development. The findings indicate that integrating bottom-up community engagement with top-down institutional support can lead to more effective and sustainable urban regeneration. The study concludes that a combined approach, leveraging both grassroots initiatives and formal governance structures, is crucial for the successful upgrading of informal settlements. The findings contribute to the urban studies literature by providing insights into the synergies between supply and demand perspectives in the context of informal settlement upgrading, offering implications for policy and practice in similar urban settings globally.

1. Introduction

Throughout history, governmental bodies have implemented a variety of slum upgrading projects and programs with varying scales and scopes. However, despite the accumulation of experience and knowledge in this field, the proliferation of slums and informal settlements continues to escalate, particularly in regions such as Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America [1,2].

In the publication by UN-Habitat titled “Streets as Tools for Urban Transformation in Slums: A Street-Led Approach to Citywide Slum Upgrading”, a paradigm shift is advocated for, moving away from fragmented, project-based upgrading efforts towards a more comprehensive, program-scale approach. This approach reframes slums not as isolated pockets of poverty and informality but as integral components of the urban fabric, albeit spatially segregated and disconnected due to a lack of adequate street infrastructure and open spaces. By recognizing streets as natural conduits that link slums with the broader urban context, the report proposes a fundamental reorientation towards leveraging streets as the primary catalyst for citywide slum upgrading initiatives [3].

The street-led approach is grounded in the recognition that streets are not merely spaces for movement but are vital for the economic, social, and cultural life of communities. This approach aligns with the theories of urban sociologists like Jane Jacobs (1961) [4], who emphasized the importance of vibrant street life for city health, and Jan Gehl (2010) [5], who focused on human-scale urban planning. In informal settlements, streets often serve as crucial venues for informal economies, social interaction, and communal activities, making them key leverage points for urban upgrading [3].

The phenomenon of informality within the Egyptian urban landscape is reflective of broader patterns of urbanization observed globally following World War II. This period marked a significant acceleration in urban development pressures, leading to the emergence of informal settlements as a direct consequence of housing market inefficiencies. These settlements often originate from the construction of temporary shelters by low-income populations, which gradually evolve into more permanent structures [6,7,8]. In response to the challenges presented by these informal settlements, the Egyptian government has implemented several initiatives aimed at urban improvement and regularization. Initiatives such as the Informal Settlements Development Program (1994–2004), which focused on the provision of basic urban infrastructure, and the Informal Settlements Preparation Program (2004–2008), aimed at mitigating the expansion of informal areas, have been pivotal. The establishment of the Informal Settlements Development Fund (ISDF) in 2008 and the change of its name and scope of work to the Urban Development Fund (UDF) in 2021 further demonstrate the government’s commitment to addressing the complexities of urban informality, signaling a strategic shift towards more integrated urban management practices [3].

The commitment of Egyptian universities to societal development, particularly in addressing the complexities of urban informality, has historically been confined to theoretical exploration rather than practical application. This gap between academic research and actionable solutions has been evident in the limited impact of numerous postgraduate studies and dissertations on addressing the challenges posed by informal urban development. Recent feedback from academic circles underscores the necessity for approaches that are not only integrated and comprehensive but also span across interdisciplinary, trans-disciplinary, and synergetic domains, thereby ensuring alignment with the practicalities of implementation challenges [9]. In response to these identified needs, the establishment of Centers of Excellence (CEs) has shown promising potential in bridging the theoretical–practical divide. For instance, the Center of Excellence for Urban Development (CEUD) in Bangladesh, inaugurated in 2017 with the backing of the World Bank and the collaborative efforts of four local institutions, aims to significantly improve urban living conditions [10]. Similarly, the Center of Excellence in Good Governance at Addis Ababa University, under the umbrella of the African Research Universities Alliance (ARUA), operates in conjunction with 15 universities across nine African countries. It oversees 13 Centers of Excellence in various fields, such as Urbanization and Habitable Cities, Climate and Development, and Good Governance. This initiative underscores the critical role that universities play in fostering multidisciplinary partnerships aimed at tackling contemporary challenges [11].

The establishment of the Alexandria University Centre of Excellence for Smart Urban Governance (ALEXU-CoE-SUG) is a strategic outcome of a funding initiative by the Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) (2020). This initiative was part of a broader call for projects focused on “Establishing Centres of Excellence in Urban Governance for Unplanned Areas through Trans-/Inter-disciplinary Projects”. The operational philosophy of the ALEXU-CoE-SUG embraces a holistic model for local development, which incorporates a nuanced understanding of the myriad external influences shaping urban upgrading endeavors. Central to its approach is the application of the Demand for Good Governance (DFGG) model, which was introduced in the World Bank report entitled “Governance and Development” in 1992 and then conceptualized in the 2000s. This model advocates for a harmonious integration of top-down governance mechanisms (supply) with dynamic, indigenous community-led initiatives (demand), aiming to foster a balanced coexistence between governing entities and the community forces at play [12].

This paper addresses the critical gap in integrating grassroots community engagement with formal institutional support for upgrading informal settlements. Traditional approaches often separate top-down governance from bottom-up initiatives, leading to interventions that are either unsustainable or ineffective. This study bridges that divide by demonstrating how a combined strategy enhances urban regeneration’s effectiveness and sustainability. Existing literature highlights the limitations of using top-down and bottom-up approaches in isolation, where top-down methods overlook local needs and bottom-up approaches lack institutional support [13,14,15,16]. By integrating these perspectives, the research provides a comprehensive framework that leverages local dynamics and governmental agendas, offering new insights for policy and practice in urban settings worldwide. This aligns with the need for holistic and inclusive urban development strategies advocated by recent studies on participatory governance and community-led planning [3,17].

Urban sustainable development aims to create inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities, as outlined by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [18]. Informal settlements, marked by inadequate infrastructure, limited services, and socio-economic marginalization, challenge these goals. Traditional upgrading methods often fail due to their fragmented nature and lack of comprehensive frameworks that integrate governmental and community perspectives. This study addresses these deficiencies by leveraging the street-led approach and the Demand for Good Governance (DFGG) model, which enhance physical connectivity, economic vitality, and social cohesion, essential for sustainable urban development [3]. The DFGG model ensures responsive and accountable governance, promoting participatory and inclusive development [12]. This holistic approach integrates environmental, social, and economic dimensions, contributing to more resilient and equitable urban systems [19].

This study comprehensively analyzes Ezbit Hegazi, a notable informal settlement in Alexandria, Egypt, to scrutinize the applicability and efficacy of a theoretical framework predicated on the Demand for Good Governance (DFGG). Through a meticulous review of relevant literature, this research endeavors to substantiate the legitimacy of its proposed methodology. Subsequently, it delves into an in-depth exploration of Ezbit Hegazi’s potential for the implementation of such an approach. This examination commences with a detailed depiction of the community’s profile, encompassing both its physical attributes and socio-cultural dynamics. Ultimately, this paper undertakes a critical analysis of two intervention alternatives, each reflecting divergent interpretations of the DFGG concept, framed within the broader context of a street-led urban development strategy.

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative and quantitative techniques to analyze the integration of the street-led approach and the Demand for Good Governance (DFGG) model in the Ezbit Hegazi informal settlement. Using a detailed case study framework, data collection included semi-structured interviews with 23 long-term residents, participant observation, and archival research on urban development initiatives in Egypt. Spatial analysis using CAD tools mapped the physical and infrastructural characteristics of Ezbit Hegazi, while secondary data from demographic statistics, urban development plans, and policy documents provided contextual insights. The qualitative data from interviews and observations were thematically analyzed to identify patterns in community engagement and governance dynamics, and quantitative data from spatial analyses and demographic statistics were examined to support these findings. This comprehensive methodology ensures a robust examination of the interplay between top-down and bottom-up approaches in urban upgrading, contributing valuable empirical evidence to the discourse on sustainable urban development [20]. This study’s methodological rigor offers actionable insights for policy and practice in similar urban settings globally.

2. Upgrading Informal Settlements: Two Perspectives

The discourse on informal settlements reveals a complex landscape marked by diverse perspectives that challenge a singular analytical approach. The ‘Institutional’ viewpoint, rooted in urban theory, positions the emergence of informality within the broader contexts of urban poverty and globalization effects, suggesting that global phenomena such as economic crises and neoliberal governance ideologies shape the conditions within these settlements [15,19,21,22,23,24,25]. This perspective correlates macro-level pressures with local outcomes like unemployment and social exclusion, portraying residents of informal settlements as marginalized and passive [25]. In contrast, Robison (2002) introduces an ‘Ordinary’ life perspective that emphasizes the internal dynamics and everyday resilience of these communities, suggesting a more nuanced understanding of their evolution and adaptive capacities [26].

The prevailing debate on upgrading informal settlements oscillates between these two perspectives, each proposing different methodologies for intervention. The ‘Institutional’ approach seeks to address structural deficiencies but has been critiqued for its potential to perpetuate stereotypes and stigmatization of settlements’ residents [25]. This critique points to the necessity of transcending a purely structural analysis to embrace the complexities of informal settlements, incorporating insights into local contexts, community agency, and cultural dynamics for more effective upgrading strategies [21,27].

The ‘Institutional’ perspective, while insightful, often neglects the heterogeneity and resilience inherent within informal settlements. Bayat and Soliman highlight the dangers of homogenizing these communities, advocating for upgrading strategies that are tailored to the unique characteristics and needs of each settlement [15,28]. Robison reinforces the need for a balanced approach that considers both the external pressures and the internal dynamics of these communities, suggesting that such an understanding is crucial for sustainable development efforts [26].

Experiences from the field further illuminate the limitations of relying solely on institutional approaches for upgrading informal settlements. Scholars like De Soto, Mitlin and Satterthwaite, and Roy have documented the challenges posed by top-down interventions, including the neglect of community participation and the diverse socio-economic fabrics that define these settings [13,14,29]. This body of work underscores the importance of engaging with the community and leveraging local knowledge for upgrading initiatives [30,31].

Power dynamics within informal settlements play a critical role in shaping their development trajectories, yet they are often overlooked by traditional institutional frameworks. The literature suggests that informal settlements are not merely the result of structural failings but also represent adaptive responses to urban housing shortages [32,33]. Fernandes (2014) [16] and others have pointed out the detrimental effects of ignoring informal governance structures in these communities, advocating for approaches that recognize and engage with these systems.

The effectiveness of upgrading strategies is further demonstrated through practical examples and alternative approaches that emphasize community engagement and resilience. Initiatives like the ‘Community-Led Participatory Planning’ and the Baan Mankong program highlight the potential of empowering residents to lead their developmental processes, ensuring that interventions are grounded in the real needs and aspirations of the community [34,35]. Similarly, strategies focusing on ‘Adaptive Reuse and Incremental Development’ and ‘Promotion of Livelihood Diversification and Economic Empowerment’ showcase the importance of acknowledging and building upon the existing assets and capacities within informal settlements [36,37].

3. Pathways to Improvement: Leveraging Street-Led Tactics for Informal Settlement Renewal

The street-led approach to urban upgrading is robustly supported by key urban theories emphasizing resident participation and local dynamics. Henri Lefebvre’s “Right to the City” advocates for democratic urban spaces where community needs drive development, which the street-led approach operationalizes by transforming streets into active public spaces [13,38]. John Friedmann’s “Transactive Planning” underscores collaborative planning and mutual learning between planners and residents, aligning with the street-led approach’s emphasis on context-specific, community-involved planning [34,39]. David Harvey’s “Social Justice and the City” highlights the importance of equitable resource distribution and socio-economic justice, principles that the street-led approach addresses by integrating local knowledge and promoting inclusive urban environments [3,40]. These theories collectively validate the street-led approach as an effective strategy for creating inclusive, participatory, and just urban spaces.

The street-led approach to upgrading informal settlements presents a transformative strategy that integrates physical infrastructure development with social, economic, and environmental improvements. Central to this discourse is the proposition that streets act as pivotal public spaces, facilitating essential social interactions and economic transactions. Drawing on the seminal works of Turner (1976) [41] and the insights provided by the United Nations Human Settlements Programme [42], this argument underscores the significance of street design and governance in promoting vibrant community life. The intrinsic value of streets extends beyond mere thoroughfares, positioning them as critical venues for social inclusivity and economic activities, thereby enhancing the urban experience for inhabitants of informal settlements. Roy (2005) highlights the importance of participatory planning in this approach, where communities are involved in the design and implementation of street layouts and public spaces [14]. This engagement ensures that interventions are tailored to the unique needs of the community, fostering a sense of ownership and accountability among residents. Such participatory processes are pivotal in creating sustainable urban environments that reflect the aspirations and identities of their inhabitants [43].

Moreover, the street-led approach directly contributes to public health and safety enhancements within informal settlements. Appadurai (2001) discusses how improved street layouts can lead to better sanitation services, waste management, and access to clean water, significantly reducing the prevalence of waterborne diseases [17]. Additionally, well-designed street networks enhance safety by improving visibility and accessibility, thereby deterring crime and creating safer environments for residents.

Economic revitalization is another critical benefit of the street-led approach. As De Soto (2000) points out, the establishment and formalization of street markets and commercial areas can catalyze local economic growth [29]. This process not only provides residents with livelihood opportunities but also facilitates the integration of informal economies into the formal sector. By doing so, it contributes to the overall economic development of the area, offering pathways out of poverty for many residents.

3.1. Street-Led Approach between Top-Bottom, and Bottom-up Understanding

The debate surrounding the street-led approach to upgrading informal settlements centers on its alignment with either a traditional institutional framework or a grassroots-oriented methodology, highlighting the dichotomy between formal institutional involvement and community-driven efforts in urban development. Institutions, including governmental bodies and international organizations, are often viewed as essential for orchestrating the upgrading process, advocating for centralized planning and uniform interventions to address housing, infrastructure, and service deficiencies [44,45,46]. This perspective underscores the role of governmental entities in establishing policies, laws, and regulations that facilitate the formalization of informal settlements and enhance living standards through state-led efforts such as slum eradication and large-scale infrastructure projects [47].

However, this institutionally driven approach tends to prioritize physical upgrades without fully considering the specific needs, desires, and socio-economic contexts of the communities involved. Critics like Mitlin and Satterthwaite (2013) argue that relying on urban planning specialists for the design and implementation of upgrading strategies can lead to technocratic solutions that overlook local knowledge, cultural practices, and community participation [13]. As a result, such interventions may not effectively address the diverse needs of informal settlement residents, potentially perpetuating issues of poverty, inequality, and exclusion [14]. Research has shown that top-down approaches often fail to build trust within communities, leading to resistance and lack of engagement from residents [14,48,49,50].

In contrast, the grassroots approach emphasizes empowering local communities to lead their upgrading processes, taking into account their distinct needs, aspirations, and capabilities [18]. Fernandes (2014) highlights the value of community-driven initiatives, grassroots organizations, and participatory methodologies that allow residents to identify their priorities, mobilize resources, and implement tailored solutions [16]. This strategy champions local empowerment and ownership, recognizing the critical role of social cohesion, social justice, and resilience in the sustainable development of informal settlements [14]. It advocates for collaborative decision-making and the integration of government bodies, communities, and other stakeholders in the upgrading process, aiming to ensure that interventions are inclusive, responsive, and sustainable [51]. Studies have shown that community-driven projects are more likely to succeed because they harness local knowledge and foster community buy-in [17,34,49,50].

By fundamentally championing the principles of grassroots engagement, the street-led approach serves as a foundational strategy for transforming informal settlements into integrated, vibrant urban spaces [52,53]. This methodology prioritizes community empowerment, participatory governance, and adaptable strategies, inherently aligning it more closely with the grassroots methodology than with top-down planning paradigms. Such an orientation is crucial for ensuring that upgrading initiatives are not only sensitive to local contexts but also meet the specific needs of communities through resident-driven initiatives [54,55]. This is supported by findings from various international projects, where the integration of community perspectives has led to more sustainable and effective outcomes [3,49,50,56].

Acknowledging the limitations of top-down planning, the street-led approach underscores the importance of embracing a grassroots perspective. This shift highlights the indispensable role that community-led actions play in fostering inclusive and sustainable urban development [57,58]. Consequently, even though the street-led approach may integrate elements from both top-down and grassroots paradigms, its core lies in empowering local communities. This empowers them to lead the change process, ensuring that the transformation of informal settlements is both inclusive and reflective of the community’s aspirations. The street-led approach addresses limitations of the institutional approach by prioritizing local knowledge and community needs, thus fostering interventions that are context-sensitive and sustainable [3,10]. This dual perspective ensures that development is holistic and deeply rooted in the lived experiences and aspirations of the residents, making it more effective and enduring.

3.2. Demand for Good Governance (DGG) as a Base for Effective Street-Led Interventions

Recent literature on urban informality and governance underscores the necessity of interdisciplinary approaches to address the complexities of informal settlements, which are integral to urban economies and service provision but often overlooked by traditional planning frameworks [59,60]. This body of work highlights informality as a dynamic system interacting with formal urban processes, advocating for participatory governance that includes the voices of informal settlement residents in policymaking [61]. The COVID-19 pandemic has further revealed the resilience of informal settlements and the critical role of community-led initiatives in crisis response, prompting a reevaluation of urban governance strategies [62].

The Demand for Good Governance (DFGG) framework, conceptualized by the World Bank, emphasizes civic participation, transparency, accountability, and responsiveness in governance. It has been applied in various global contexts with notable success. In Kenya, the framework was integrated into the Kenya Informal Settlements Improvement Project (KISIP), enhancing community-driven planning and resource allocation, which led to better service delivery and improved living conditions [56]. Similarly, in the Philippines, the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) incorporated DFGG principles, promoting transparency and community involvement in land redistribution, thereby increasing land tenure security and agricultural productivity [63]. These applications demonstrate the DFGG framework’s effectiveness in fostering inclusive, participatory urban governance, aligning governmental actions with community needs and aspirations and improving the sustainability of urban development initiatives.

Governance encompasses the processes and structures that ensure effective, transparent, and accountable decision-making in organizations and societies [64]. Good governance highlights principles like the rule of law, inclusiveness, and accountability [65]. However, the Demand for Good Governance (DFGG) framework adds a critical dimension by emphasizing active citizen engagement and mechanisms for social accountability, enabling citizens to demand better governance practices [66]. Unlike traditional good governance, DFGG focuses on participatory governance where civic involvement directly influences governance outcomes, enhancing responsiveness and accountability [67].

Integrating the “Demand for Good Governance” (DGG) with the “Street-Led” approach in the upgrading of informal settlements presents a transformative strategy for urban development. This integration emphasizes the empowerment of local communities and the need for governance systems to be responsive, accountable, transparent, and efficient. Drawing from the World Bank’s concept of DFGG, this strategy places citizens, civil society organizations (CSOs), and local actors at the forefront of advocating for better governance [68]. The incorporation of these principles into urban planning initiatives can lead to more participatory, inclusive, and sustainable urban environments.

The DGG framework emphasizes the essential role of grassroots involvement in governance processes. It advocates for a bottom-up approach where local communities actively participate in demanding accountability and responsiveness from public officials and service providers. This approach is supported by empirical evidence suggesting that civic engagement significantly improves governance outcomes across various sectors including health, education, and public service delivery [67,69]. By prioritizing community engagement, the DGG approach aligns closely with the ethos of the street-led model, which views streets as crucial platforms for social, cultural, and economic activities within cities [70,71].

Street-led movements, underpinned by the demand for good governance, highlight the potential for grassroots activism to enhance governance structures. These movements use various channels to demand greater transparency and accountability, thereby contributing to governance reforms that more accurately reflect community needs [72]. However, transforming these grassroots efforts into formal governance practices poses significant challenges, including political co-optation, sustaining momentum, and formalizing grassroots efforts [73]. Despite these challenges, the synergy between DGG and street-led approaches suggests a powerful framework for achieving sustainable urban development.

The Favela-Bairro Project in Rio de Janeiro serves as a prime example of the successful application of a combined DGG and street-led approach. The project aimed to weave informal settlements into the urban fabric through a comprehensive strategy involving physical, social, and legal interventions. Key to its success was a multi-tiered governance structure that facilitated the formalization of informal settlements, significantly improving land tenure security and social stability [16,74]. Community participation was emphasized, ensuring that interventions were responsive to the needs of the residents and fostering a sense of ownership and engagement within the community [46,75].

Finally, the amalgamation of DGG principles with the street-led approach offers a robust framework for the upgrading of informal settlements. By fostering a governance environment that is responsive to and reflective of community needs, this approach enhances the effectiveness and sustainability of urban upgrading initiatives. It represents a promising pathway towards creating more integrated, vibrant, and inclusive urban spaces, demonstrating the potential of aligning governance reforms with grassroots activism.

4. ALEXU-CoE-SUG’s Approach to Excellence: Systematic Interventions and Outcomes

The Alexandria University Centre of Excellence for Smart Urban Governance (ALEXU-CoE-SUG) was initiated with funding from the Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) [76]. This initiative focuses on enhancing urban governance in unplanned areas. The Centre’s funding is based on rigorous criteria across three main areas: Project Quality, which evaluates the project’s scientific merit and the clarity of its goals and methodology; Operational Sustainability, assessing the business model’s feasibility and sustainability, including maintenance and compliance with international standards; and Impact and Collaboration, which examines the project’s socio-economic impact potential, its ability to enhance indigenous knowledge, and its effectiveness in fostering collaborations.

This proposal, developed by the ALEXU-CoE-SUG consortium, offers a thorough analysis of informality within the Egyptian urban context, recognizing its significant economic contributions and widespread presence. It shifts the narrative on informality from a perceived shortcoming to a reflection of resilience and untapped value, as supported by UN-Habitat (2020) [1]. It conceptualizes informal settlements as dynamic entities with the potential for sustainable development and integration into broader societal growth through a “Regeneration” paradigm, aligning with modern urban development strategies [10].

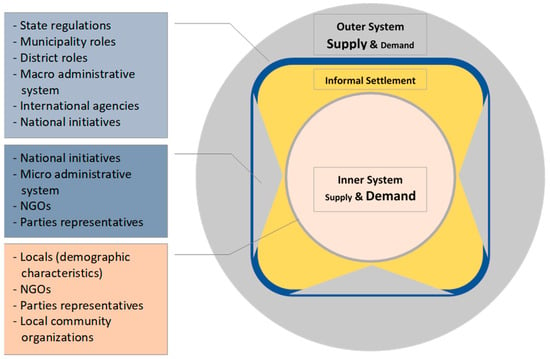

This strategy champions a harmonized engagement between the demand for active community involvement and the supply of effective governance in urban settings (Figure 1). It seeks to elevate local communities to the role of empowered stakeholders, advocating for a “Demand” side that is as vigorous and involved as the “Supply” side, which calls for governmental bodies to embrace and implement governance models centered on the “Demand for Good Governance” [10]. By presenting a holistic approach that navigates through the historical depth, present condition, and future aspirations of informal settlements, this plan integrates a variety of actions including the mapping of settlement histories, the use of cutting-edge technology for real-time expansion monitoring, and the predictive modeling of future development trends. This comprehensive strategy aims to tap into the untapped potential within informal settlements, steering towards an urban development paradigm that is more inclusive, participatory, and sustainable [10,68]. Within this framework, Ezbit Hegazi is identified as a key informal settlement for a pilot study to explore its capacity for adopting street-led development principles, showcasing the practical implementation of these innovative governance strategies.

Figure 1.

The ALEXU-CoE-SUG approach to balancing supply and demand dynamics in informal settlements.

4.1. Navigating Ezbit Hegazi: Challenges and Realities of Informal Living in Alexandria

Informal settlements in Alexandria, Egypt, present significant challenges to urban development, manifesting in inadequate housing and restricted access to basic services. These areas have transitioned from peripheral to central components of the urban core as the city expands, often without formal property rights or adequate infrastructure. This lack of formalization contributes to heightened health risks among residents [6,18].

To address these issues, various strategies encompassing policy reforms, community engagement, and infrastructural enhancements have been deployed. Initiatives have aimed to improve living conditions and establish legal land tenure, with historical efforts dating back to the late 1970s. These initiatives have progressively adopted comprehensive approaches, including the National Slum Upgrading Strategy supported by the World Bank, and post-2011 revolution efforts like the Informal Settlements Development Facility, aligning with the Sustainable Development Strategy: Egypt Vision 2030 [6,18,23,77,78].

However, critiques of these efforts focus on the sustainability of interventions, the depth of community engagement, and potential for increasing urban inequality through mechanisms like gentrification. These critiques highlight the necessity for strategies that are both inclusive and capable of addressing the root causes of informal settlement proliferation [6,18,23].

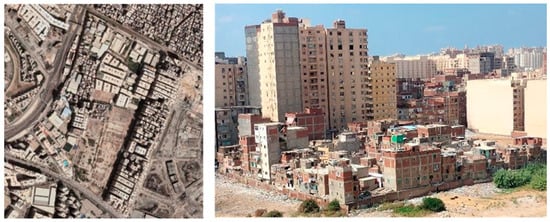

Within this context, Ezbit Hegazi serves as a case study in the potential for urban regeneration. Located near the Smouha district and along the Al-Mahmoodeya Axis, this informal settlement is strategically placed within Alexandria’s Eastern District, according to the city’s governmental division into six districts [79]. Covering approximately 208 feddans, Ezbit Hegazi has seen considerable densification over two decades, a testament to its resilience and unique spatial configuration, influenced by geographical constraints like the Al-Mahmoodeya Axis and the Alexandria–Cairo train railway. These features not only facilitate its integration into the broader urban fabric of Alexandria but also highlight opportunities for sustainable regeneration [1].

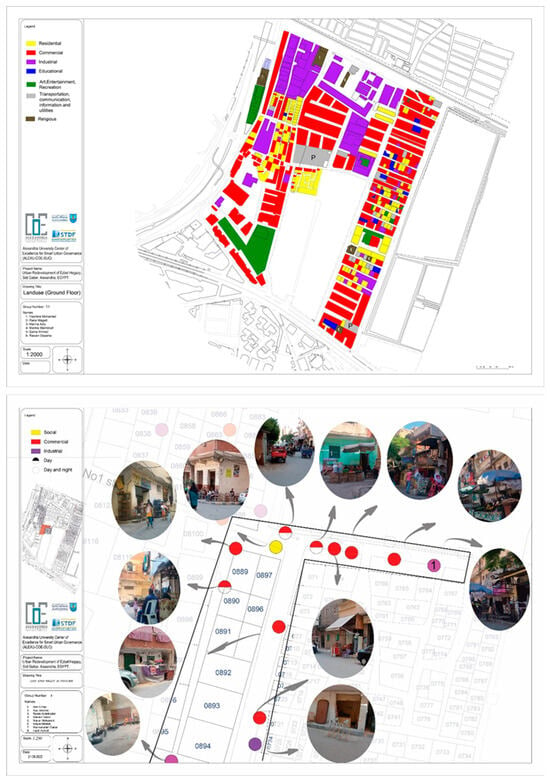

Ezbit Hegazi’s urban and physical structure, characterized by a grid pattern with a main artery linking the eastern Al-Mahmoudiya Axis with the western train railway, presents significant opportunities for enhancement (Figure 2). Despite some paved roads, the primary artery is neglected and in dire need of upgrades. The settlement’s building conditions are generally acceptable, with structures of 4–5 stories constructed from quality materials. However, the absence of open public spaces indicates a critical need for areas dedicated to social engagement and community activities, underscoring the potential for strategic urban improvements [80,81].

Figure 2.

The location and physical morphology of Ezbit Hegazi.

The demographic and socio-historical context of Ezbit Hegazi, an urban informal settlement, is deeply rooted in its historical development, dating back to the construction of the Mahmoudiya Canal nearly two centuries ago. This historical milestone has shaped the settlement’s demographic composition, with the current population of approximately 32,000 residents primarily consisting of descendants from families originating at the time of the area’s early development. Notably, families such as the Ghanem, Abu El-Saud, and El-Mazin, among others, have maintained a continuous presence, supplemented by a relatively small influx of newcomers. This enduring lineage underscores the unique demographic stability within the fabric of Ezbit Hegazi’s community.

Moreover, the settlement demonstrates a notably stable security situation, devoid of criminal hotspots or significant incidents of violence, with infrequent conflicts being amicably resolved through established community leadership. The modalities of land and building ownership within Ezbit Hegazi are characterized by traditional norms of long-standing possession, ensuring property continuity without formal disputes for many years. Infrastructure and service provision have seen incremental improvements over time, marked by key developments such as the installation of the first public water faucet in 1915, the introduction of electricity around 1972, and significant urban infrastructure advancements like road paving, which commenced around 1995. These milestones reflect the gradual but steady progress in improving the living conditions and infrastructure within the settlement.

4.2. (ALEXU-CoE-SUG) Interventions in Ezbit Hegazi

The Alexandria University Centre of Excellence for Smart Urban Governance (ALEXU-CoE-SUG) has embarked on a comprehensive initiative aimed at fostering sustainable urban development through a series of layered activities across various domains. Within the academic sphere, under the ethos of “the social responsibility of the architect”, the ALEXU-CoE-SUG introduced innovative projects to the design studios of the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, at Alexandria University. These projects, grounded in an immersive approach, involved students conducting site inspections and engaging with local residents in Ezbed Hegazi to identify their needs. This engagement unveiled a critical gap in safe recreational spaces for children, prompting the proposal for a children’s adventure playground designed with safety, affordability, and sustainability in mind. This initiative expanded to include proposals for an outpatient clinic and a social service center, addressing further community needs on adjacent land parcels.

Further in-depth community studies revealed a pronounced lack of healthcare facilities and highlighted the unique social dynamics of the area, characterized by a strong community bond and a historical unregistered customary assembly. The separation of the area by the development of the new Mahmoudya axis road further accentuated its isolation, likening it to an island cut off from essential services. The existing infrastructure, such as a guest house adjacent to the mosque, underscored the community’s resourcefulness and potential for further development to meet pressing needs, including healthcare. Challenges such as youth unemployment and the potential descent into drug abuse were identified, with community suggestions pointing towards the establishment of a youth club as a mitigative strategy.

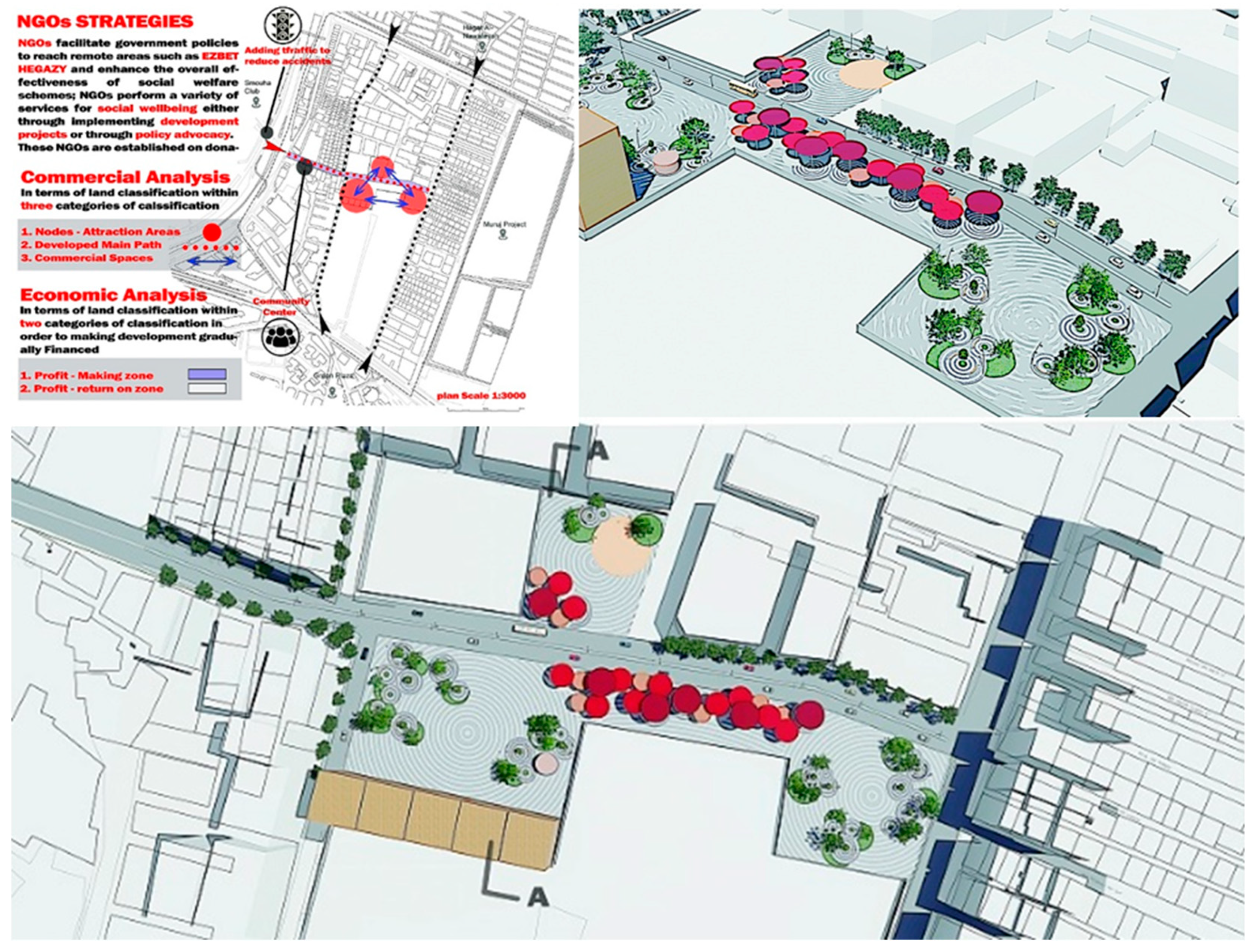

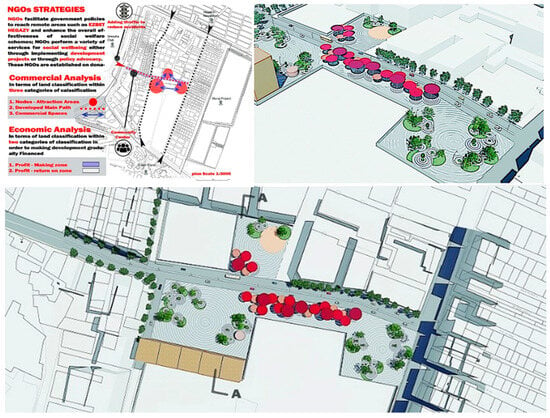

An investigation into the role of supporting NGOs revealed a vibrant ecosystem of local and external support mechanisms. The customary association, funded by family contributions, plays a pivotal role in managing a guest house for various community services, despite facing bureaucratic challenges (Figure 3). This grassroots approach to community support, alongside the contributions from the Talaat Mustafa and Mohamed Rashid Foundations, illustrates a multi-tiered support network. These foundations, through their in-kind support and economic activities, have been instrumental in addressing the dual social and economic challenges faced by the community.

Figure 3.

Site visits and working with locals in Ezbit Hegazi.

Despite the notable efforts by local NGOs and foundations, socio-economic challenges persist, with severe poverty affecting certain demographics within the area. The sporadic aid provided by the Rashid and Talaat Mustafa Foundations, though valuable, falls short of addressing the systemic issues of unemployment and lack of access to essential services. The employment landscape, dominated by external workers, underscores the need for targeted initiatives to enhance local employment opportunities, with healthcare, social services, and small business development identified as priority areas.

Engagements with government representatives and the General Authority of Physical Planning (GAPP) have opened dialogues on the future of Ezbit Hegazi, set against the backdrop of government plans for urban redevelopment and the displacement of informal settlements. The ambiguity of the government’s vision, oscillating between integration and relocation strategies, presents both a challenge and an opportunity for leveraging these plans to benefit the Ezbit Hegazi community. This situation underscores the importance of strategic negotiations to ensure that urban development initiatives align with the community’s needs and aspirations.

However, the multifaceted approach taken by the ALEXU-CoE-SUG in Ezbit Hegazi illustrates a model of integrated urban development that balances academic innovation, community engagement, NGO support, and governmental dialogue. This model emphasizes the critical role of architecture and urban planning in addressing social responsibility and underscores the potential for collaborative efforts to foster sustainable and inclusive urban environments.

To further contextualize the Ezbit Hegazi case study, it is beneficial to compare it with other global initiatives in informal settlement upgrading, as shown in Table 1. For instance, the Kampung Improvement Program (KIP) in Indonesia focused on community-driven efforts to enhance infrastructure, sanitation, and housing, which resulted in significant improvements despite challenges in maintaining engagement and funding [82]. Similarly, South Africa’s Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP) aimed at in situ upgrades and tenure security, which improved living conditions and legal status for residents but faced issues related to scalability and community resistance [48]. In the Philippines, the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) leveraged participatory governance and social accountability, leading to improved land tenure and infrastructure development, although political resistance and funding constraints posed challenges [63].

Table 1.

Comparing global initiatives in informal settlement.

Comparing these initiatives with Ezbit Hegazi, where the integration of the Demand for Good Governance (DFGG) framework and the street-led approach has shown promising results, provides a richer empirical background. The Ezbit Hegazi project, which combines top-down institutional support with bottom-up community engagement, ensures that interventions are inclusive and responsive to local needs. This approach not only aligns with the successes seen in KIP and UISP, where community participation was crucial, but also addresses their challenges by incorporating stronger governance mechanisms to enhance sustainability and accountability [13]. By situating Ezbit Hegazi within these broader global patterns of urban informality, we can better understand the critical factors that contribute to the success or failure of informal settlement upgrading projects, thereby offering valuable insights for future initiatives.

5. Decoding the Spatial Logic of Ezbit Hegazi: A Precursor to Street-Led Development Initiatives

The spatial configuration of Ezbit Hegazi exhibits a non-linear grid pattern, diverging from the uniformity characteristic of meticulously planned urban environments. This configuration suggests an organic development trajectory, possibly as a consequence of ad hoc adaptations to residents’ immediate spatial requirements and constraints, rather than emanating from a structured urban planning paradigm. The urban morphology of the Ezbit Hegazi informal settlement demonstrates compact clustering, underscored by a principal arterial route demarcating one boundary of the settlement. This route serves as the primary ingress, linking directly to the Al-Mahmoudia Axis and aligning with the broader urban infrastructure matrix. Within the confines of the settlement, the differentiation of road hierarchies blurs, giving way to a network of narrow pathways and alleys that unfold in a complex, maze-like pattern, emblematic of piecemeal and unregulated urban expansion.

The settlement is characterized by a high density of closely situated structures, indicative of its informal developmental genesis. The heterogeneity in the dimensions and configurations of buildings reflects the absence of standardized construction protocols, a hallmark of self-organized settlements where building activities are predominantly resident-led. The spatial layout does not explicitly designate public domains such as plazas, parks, or communal facilities, which are generally limited or seamlessly assimilated into the fabric of informal settlements. This lack of formally designated public spaces typically leads to the appropriation of leftover spaces for community engagements. Furthermore, the settlement lacks formal zoning regulations, which, in conventional urban planning, would prescribe specific land uses for residential, commercial, industrial, and recreational purposes. Instead, a mixed-use milieu prevails, with residential and commercial functions intermingling closely, a characteristic trait of such communities.

In essence, this analysis elucidates the intricate socio-spatial dynamics inherent in Ezzbit Hegazi (Figure 4), setting the stage for the implementation of street-level interventions by the Alexandria University Centre of Excellence for Smart Urban Governance (ALEXU-CoE-SUG). These interventions aim to navigate and potentially rectify the spatial complexities identified, leveraging the settlement’s unique urban fabric to foster more sustainable urban living conditions.

Figure 4.

Ground floor utilization and open-air activities in Ezbit Hegazi: indicators of a socio-economically dynamic community.

The methodology employed by the ALEXU-CoE-SUG for interventions is intricately designed to leverage the symbiotic relationship between institutional frameworks, which predominantly concentrate on the tangible aspects of development, and the inherent potential of grassroots movements to spearhead community-based initiatives. This approach delineates two distinct yet interwoven tracks, meticulously crafted to address the requisites of both spheres. These tracks have been conceptualized following rigorous dialogue and negotiations with stakeholders representing both dimensions, ensuring a comprehensive understanding and integration of their needs. At the core of these discussions is the implementation of Demand for Good Governance (DGG) principles. These principles serve as the foundational bedrock for deliberations, facilitating a structured discourse on pivotal questions such as the determination of authority over decisions regarding the nature of implementations and the methodologies for execution. By anchoring the conversation in DGG principles, this methodology seeks to ensure that the processes are not only inclusive but also reflective of a balanced consideration of both the physical development aspects and the activation of community-driven endeavors.

In operational terms, the ALEXU-CoE-SUG delineated two distinct intervention proposals, each mirroring the unique viewpoints inherent within the dual-track framework. These propositions were instrumental in materializing the conceptual visions of each faction, thereby fostering a collaborative milieu that amalgamates divergent perspectives. This process of intervention delineation is characterized as follows.

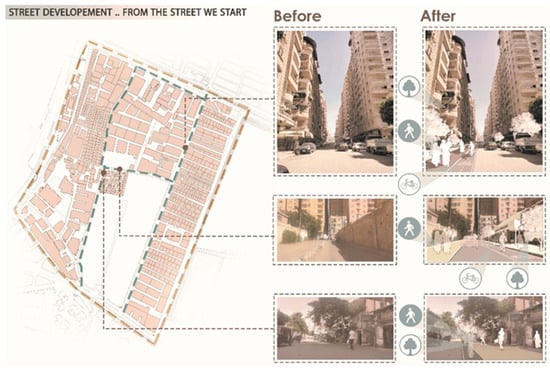

5.1. The First Proposal

The first proposal is predicated on an institutional vision that seeks to ameliorate the physical landscape of informal settlements by integrating them more cohesively into their broader physical milieu (Figure 5). This vision is operationalized through a targeted intervention within the vicinity of Ezzbit Hegazi, where a comprehensive revitalization of principal thoroughfares is envisaged to forge a robust physical linkage with the area’s extended environment. The envisaged reconfiguration is aimed at equipping these arterial routes with essential infrastructure, thereby enabling them to function as conduits for service delivery to the encompassing region. Integral to this intervention is the strategic deployment of healthcare and educational facilities along these newly enhanced arterial channels, ensuring the provision of vital services directly within the community’s fabric. Additionally, the introduction of vegetation and landscaping features is anticipated to redefine the urban aesthetic, contributing to a transformed urban landscape. This approach is grounded in the conviction that physical enhancements to the environment are intrinsically linked to broader improvements in the quality of life for residents, thereby reflecting a holistic enhancement across various aspects of community life.

Figure 5.

The first proposal: institutional-based intervention in Ezbit Hegazi.

5.2. The Second Proposal

The second proposal outlines a meticulously devised urban regeneration strategy for the Ezbit Hegazi informal settlement, predicated on a street-centric framework that accords precedence to the socio-economic needs of the resident community (Figure 6). This approach articulates the reconfiguration of extant urban thoroughfares into multifaceted public domains, posited as the cornerstone of the settlement’s rejuvenation efforts. The deployment of modular units along these arteries is posited as a mechanism for the promotion of commercial enterprises, ostensibly catalyzing local entrepreneurship and contributing to economic enhancement.

Figure 6.

The second proposal: community-based intervention in Ezbit Hegazi.

The design incorporates spaces designated for networking, envisaged as informal congregational areas that are anticipated to foster communal engagement and augment the social fabric of the settlement. Integral to this intervention are the establishment of verdant corridors along the main routes, distinguished by a profusion of foliage and arboreal elements, thereby augmenting the ecological and visual appeal of the urban landscape. These corridors are multifunctional, serving as communal spaces, advancing environmental sustainability through urban greening initiatives, and potentially mitigating the effects of urban heat islands.

This strategy encompasses critical infrastructural enhancements, including the refinement of water, sanitation, and electrical systems, seamlessly integrated within the urban fabric to facilitate efficacious service delivery. The judicious placement of healthcare and educational infrastructures along these conduits is indicative of a commitment to ameliorating access to indispensable services, in alignment with the overarching objective of social betterment.

The scope of this plan is extensive, providing a holistic overview that encapsulates the integration of the settlement within the broader urban matrix while concurrently addressing details pertinent to enhancing the quality of life on an individual level. Collectively, this intervention aims to foster a harmonious amalgamation of physical environment improvements and the establishment of a resilient socio-economic milieu, which is attentively responsive to the diverse needs and ambitions of the Ezbit Hegazi community. This approach delineates a paradigm of urban renewal that is both inclusive and sustainable, potentially serving as a model for similar contexts globally.

6. Discussion

Each proposal encapsulates a unique approach to revitalization, with the first proposal emphasizing the physical integration of the settlement into its broader context through infrastructure enhancement, while the second proposal prioritizes socio-economic upliftment via a street-centric regeneration strategy.

The first proposal focuses on physical enhancements, positing that the restructuring of principal thoroughfares and the introduction of critical infrastructure, such as healthcare and educational facilities, can significantly improve the quality of life for residents. This approach not only aims to enhance service delivery but also to aesthetically transform the urban landscape through the introduction of vegetation and landscaping features.

Conversely, the second proposal champions a socio-economic model that leverages street redesign as a catalyst for community development. By reimagining thoroughfares as vibrant public spaces, this strategy seeks to foster local entrepreneurship, community engagement, and environmental sustainability through the introduction of modular units for commercial activities, communal spaces for networking, and verdant corridors for ecological enhancement.

Both proposals, though distinct in their primary focus, share the underlying principle of improving life in Ezbit Hegazi. However, integrating these proposals into a unified action plan can offer a more comprehensive solution to urban upgrading, embodying the principles of Good Governance within a street-led framework.

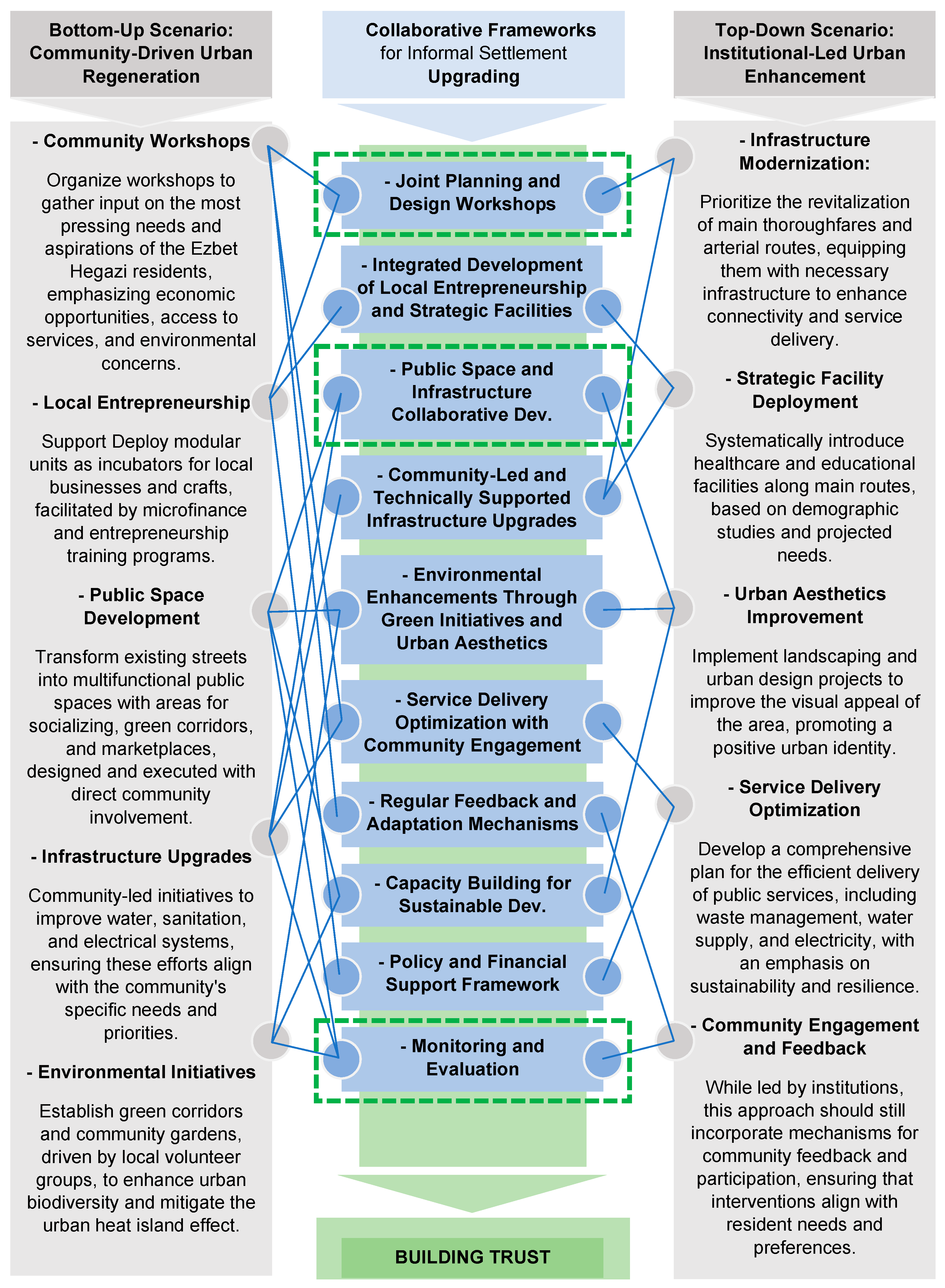

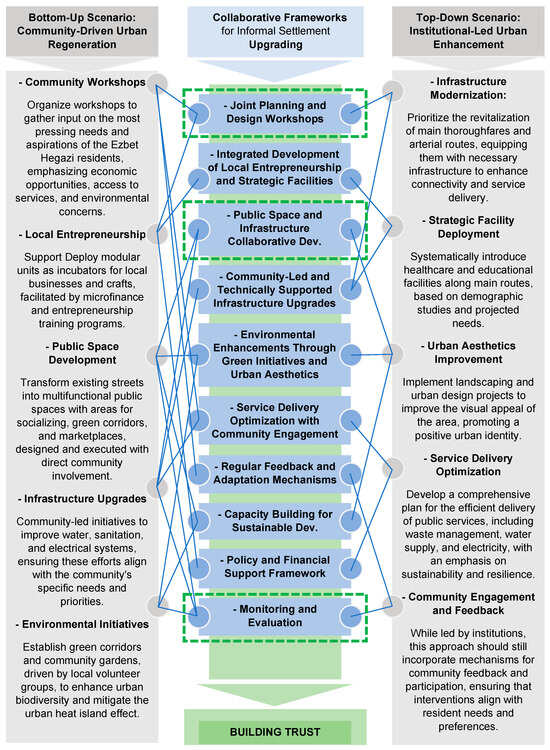

To further elaborate an action plan, the ALEXU-CoE-SUG envisions two scenarios: one following a bottom-up approach and another utilizing a top-down methodology. These scenarios aim to synthesize the benefits of the described proposals into a unified action plan, leveraging street-led practices as a pivotal element within a broader governance context.

6.1. Bottom-up Scenario: Community-Driven Urban Regeneration

The objective of this scenario is to empower the Ezbit Hegazi community by engaging them directly in the decision-making and implementation processes, focusing on socio-economic development and environmental sustainability. This scenario encompasses a number of activities beginning with organizing community workshops to identify the residents’ primary needs and aspirations, including economic growth, improved service access, and environmental sustainability. Following this, support for local entrepreneurship will be provided through modular units serving as business incubators, complemented by microfinance and training programs. The development of public spaces will transform streets into areas for socializing, green spaces, and markets, with designs stemming from active community participation. Infrastructure improvements will be community-driven, targeting essential services like water, sanitation, and electricity, tailored to meet local demands. Additionally, environmental efforts will introduce green corridors and community gardens to increase biodiversity and counter the urban heat island effect, with initiatives led by local volunteers.

The community’s active participation and leadership in planning and implementing these initiatives exemplify DGG principles, fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility towards the urban environment and its development.

The Ezbit Hegazi project illustrates a successful integration of the Demand for Good Governance (DFGG) framework within a community-driven approach. This framework ensures continuous community participation and accountability, thereby fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility towards urban development. By comparing these initiatives with similar global projects, such as Indonesia’s Kampung Improvement Program (KIP) and South Africa’s Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP), the Ezbit Hegazi project demonstrates a comprehensive approach to urban upgrading that addresses common challenges like maintaining community engagement and scalability [48,82].

6.2. Top-Down Scenario: Institutional-Led Urban Enhancement

The objective of this scenario is to integrate Ezbit Hegazi more effectively into the broader urban context, improving infrastructure and access to essential services through strategic planning and investment. This scenario encompasses a number of activities beginning with infrastructure modernization; the focus is on revitalizing main thoroughfares and arterial routes to boost connectivity and streamline service delivery. Following this, there is a strategic deployment of healthcare and educational facilities along these key routes, informed by demographic studies and anticipated needs. To elevate the area’s visual appeal and foster a cohesive urban identity, landscaping and urban design projects will be implemented. Service delivery optimization is another cornerstone, aiming for the seamless provision of essential services like waste management, water, and electricity, with sustainability and resilience as guiding principles. Despite the top-down approach, the roadmap envisages active community engagement and feedback mechanisms to ensure that interventions resonate with the residents’ aspirations and preferences, thereby marrying institutional initiative with local insight for a comprehensive upgrade of Ezbit Hegazi.

This scenario emphasizes governance structures and institutional frameworks as the driving forces behind urban development, utilizing a systematic approach to address the complex needs of Ezbit Hegazi. It showcases a model where governance, even in a top-down approach, can incorporate elements of community feedback and participation, aligning with broader DGG principles. This scenario also highlights the practical application of Henri Lefebvre’s ‘Right to the City’ theory and John Friedmann’s ‘Transactive Planning’ model by incorporating community feedback and ensuring that institutional initiatives align with local needs and aspirations [38,39]. The integration of the DFGG framework within this top-down approach addresses the socio-economic inequalities emphasized by David Harvey, ensuring that governance mechanisms are inclusive and responsive [40].

6.3. Collaborative Frameworks for Informal Settlement Upgrading

The proposed roadmap for upgrading Ezbit Hegazi—developed by the ALEXU-CoE-SUG—articulates a synthesized action plan that leverages the strengths of both top-down and bottom-up approaches, nested within a framework that prioritizes good governance and a street-led methodology (Figure 7). This comprehensive strategy starts with infrastructure enhancement and physical integration, transforming principal thoroughfares into multifunctional spaces that facilitate not just essential services but also commercial and social activities, thus blending physical connectivity with socio-economic vitality. To foster socio-economic empowerment, the plan envisions encouraging local entrepreneurship and community engagement through the strategic placement of modular commercial units and communal spaces, enhancing socio-economic upliftment in line with urban design principles. Environmental sustainability and urban aesthetics are also key, with the integration of green corridors and public spaces to improve ecological sustainability, mitigate the urban heat island effect, and beautify the area. The roadmap proposes a holistic approach to service delivery, ensuring critical infrastructure like healthcare, education, and utilities are seamlessly integrated within the urban fabric for efficiency and accessibility. Underpinning these initiatives is a robust governance framework emphasizing transparency, accountability, and community participation, ensuring that the planning and implementation process remains inclusive, equitable, and responsive to residents’ needs, thereby marrying the best of both strategic approaches for the rejuvenation of Ezbit Hegazi.

Figure 7.

The collaborative framework for DFGG-based informal settlement upgrading.

By merging the physical and socio-economic strategies outlined in the two proposals, this integrated action plan aims to not only upgrade the urban environment of Ezbit Hegazi but also to foster a resilient, sustainable, and vibrant community. This holistic approach, grounded in the principles of good governance, exemplifies a street-led practice that could serve as a blueprint for the regeneration of similar informal settlements.

In this study, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposively selected sample of 23 residents from Ezbit Hegazi, comprising 13 males and 10 females, whose ages ranged from 28 to 62 years. These individuals have been inhabitants of the locality for a period exceeding 15 years, thereby providing a rich historical perspective on the community’s dynamics and the efficacy of past and potential urban development interventions. The interviews sought to elicit residents’ perceptions and attitudes towards proposed scenarios for upgrading their living conditions, with a specific focus on the integration of bottom-up and top-down approaches in the governance model.

The findings reveal a complex landscape of trust and skepticism towards institutional commitments. Approximately 57% of the participants expressed substantial skepticism regarding the feasibility and sincerity of institutional efforts in urban upgrades, attributing this mistrust to an accumulation of negative experiences with past governmental initiatives. This segment of the population underscores the critical challenge of rebuilding trust in any future development projects. Conversely, approximately 26% of the respondents exhibited a willingness to engage in partnerships with local government entities, indicating a cautious optimism towards the potential for co-creating a new governance model conducive to sustainable development. This group’s openness to collaboration suggests a pathway for institutional actors to foster more effective community engagement strategies. The remaining 17% of the sample expressed a conditional willingness to support the proposed upgrade scenarios, contingent upon the demonstration of genuine and substantive institutional commitment. This conditional support highlights the importance of tangible, action-based proof of commitment from governmental agencies to overcome entrenched skepticism.

The findings from the semi-structured interviews underscore the complex landscape of trust and skepticism towards institutional commitments among the residents of Ezbit Hegazi. As one resident expressed, “We’ve seen many promises over the years, but nothing ever changes. Why should I trust them now? Unless I see real benefits for myself and my family, I’m not getting involved”. This sentiment reflects a deep-seated mistrust that poses a significant challenge to the success of any urban upgrade initiative. However, there is also cautious optimism among some residents, as another noted, “I am open to working with the local government if they show they are serious about helping us. But I need to see how this will directly benefit me before I commit to anything”. This statement highlights a conditional willingness to engage, contingent on the demonstration of concrete benefits. Additionally, the interviews revealed a segment of the population with a conditional willingness to support the proposed upgrading scenarios, as articulated by one resident: “I’ll support the new plans, but only if the government demonstrates they are truly committed. They must follow through with their promises and ensure that my needs are met first before I can fully trust them”. These quotes illustrate the critical importance of addressing personal and immediate needs to rebuild trust and foster effective community engagement.

The recurrent invocation of “trust” throughout the interviews serves as a poignant indicator of the prevailing mistrust towards governmental agencies among the indigenous population. This finding underscores the imperative for establishing mechanisms of accountability, transparency, and participatory governance as foundational elements of any urban upgrading initiative. The insights derived from this study illuminate the critical dimensions of community perceptions that must be addressed to facilitate successful urban upgrading projects in informal settlements like Ezbit Hegazi.

Building on these insights, the Ezbit Hegazi case study offers valuable new lessons for the field of informal settlement upgrading by emphasizing the critical role of trust in the success of collaborative urban development projects. While the experience of Ezbit Hegazi aligns with global initiatives such as Indonesia’s Kampung Improvement Program and South Africa’s Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme, it highlights that small factors like community mistrust towards governmental agencies can significantly influence the outcomes [48,82]. The recurrent invocation of ‘trust’ throughout resident interviews underscores its importance as a foundational element for successful urban upgrading. The integration of the Demand for Good Governance (DFGG) framework within the Ezbit Hegazi project addresses these trust issues by promoting transparency, accountability, and participatory governance, ensuring that interventions are inclusive and responsive to local needs [13,66]. This focus on rebuilding trust through consistent and transparent community engagement adds a crucial dimension to the existing body of knowledge, demonstrating that fostering trust is essential for the sustainability and effectiveness of urban upgrade initiatives.

7. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights into the integration of top-down and bottom-up approaches for urban upgrading in informal settlements, it has limitations. The research is primarily based on a single case study of Ezbit Hegazi in Alexandria, Egypt, which may not be universally applicable to all informal settlements due to significant variations in socio-economic, cultural, and political contexts [86]. The study relies heavily on qualitative data from semi-structured interviews and participant observations, which, despite capturing in-depth perspectives, may introduce biases and limit the generalizability of the findings due to the small sample size [20]. Additionally, the implementation of the street-led approach and Demand for Good Governance (DFGG) model is in its early stages, with long-term sustainability and impact yet to be fully assessed, and the absence of a longitudinal component limit insights into the evolving dynamics over time [87].

Future research should address these limitations by conducting comparative studies across multiple informal settlements with different geographic and socio-economic contexts to enhance the generalizability of the findings [87]. Incorporating a mixed-methods approach that combines qualitative insights with robust quantitative data, including larger-scale surveys, statistical analysis, and GIS tools, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the interventions’ effectiveness [20]. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess the long-term impacts and sustainability of the street-led approach and DFGG model, tracking changes in infrastructure, socio-economic conditions, and governance dynamics over several years [86]. Additionally, future research should explore the role of technology and digital tools in enhancing community engagement and governance, as well as policy-oriented studies that integrate these models into national and local urban planning frameworks to provide practical guidelines for policymakers and urban planners [1,10].

8. Conclusions

This study foregrounds the complexity of upgrading informal settlements, advocating for a nuanced, multi-dimensional approach that harmonizes the strategic insights of institutional frameworks with the lived experiences of community members. It underscores the importance of acknowledging the diversity, resilience, and agency inherent within these communities, which are essential for crafting sustainable and inclusive strategies for urban renewal. Central to our discourse is the integration of global insights with local knowledge and community participation, which are pivotal in facilitating more effective and empowering interventions. This synthesis of perspectives lays a robust foundation for urban planners and policymakers aiming to foster inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities, in alignment with sustainable development goals.

This investigation into the Ezbit Hegazi settlement encapsulates a compelling argument for a transformative approach to urban revitalization. By intertwining institutional support with grassroots initiatives within a governance framework characterized by transparency, accountability, and participatory governance, our research highlights the synergy between policy-driven and community-led strategies. This approach is exemplified through the promotion of vibrant public spaces via a street-led strategy, which not only enhances social interaction and economic transactions but also bolsters socio-economic resilience and environmental sustainability. Such strategies underscore the critical role of interventions that extend beyond infrastructural improvements to include socio-economic and environmental dimensions.

Our findings, derived from semi-structured interviews with the residents of Ezbit Hegazi, illuminate the complex dynamics of trust, skepticism, and willingness to engage with intervention strategies. The skepticism towards institutional efforts underscores the urgent need for building trust through direct, beneficial community projects. Meanwhile, the openness among certain community segments towards collaboration with government entities reveals potential for trust-based, co-creative processes in urban development. The involvement of the Alexandria University Centre of Excellence for Smart Urban Governance (ALEXU-CoE-SUG) in bridging theoretical research with practical application exemplifies an impactful model for integrated urban development, addressing community needs while steering towards a sustainable urban future.

The findings from the Ezbit Hegazi case study are highly relevant to policies aimed at upgrading informal settlements globally. The successful integration of the Demand for Good Governance (DFGG) framework in Ezbit Hegazi, which emphasizes transparency, accountability, and community participation, mirrors effective strategies seen in Indonesia’s Kampung Improvement Program (KIP) and South Africa’s Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP). These programs also highlighted the importance of active community involvement in planning and implementation to build trust and address community needs [48,82]. Moreover, the focus on capacity building and empowerment in Ezbit Hegazi aligns with global practices that provide training and resources to reduce marginalization [82]. The collaborative governance structure, combining top-down and bottom-up approaches in Ezbit Hegazi, showcases a model that ensures inclusive stakeholder engagement, which is crucial for effective urban regeneration [13]. These findings underline the necessity of trust-building mechanisms and participatory governance in the success of urban upgrading policies.

In conclusion, this study advocates for a comprehensive approach to the upgrading of informal settlements, emphasizing the integration of physical, socio-economic, and environmental aspects of urban renewal. The Ezbit Hegazi case study epitomizes the efficacy of blending top-down and bottom-up strategies within a coherent governance model, providing a replicable blueprint for urban development that respects the intricate needs and aspirations of informal settlement communities. Through a governance lens focused on good practices and community engagement, our research highlights the transformative potential of urban upgrade initiatives that are attuned to the diverse realities of informal settlements, offering invaluable insights for replicable models in similar contexts worldwide.

Funding

This project was funded by the Egyptian Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF), grant number 45852.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Alexandria University Centre of Excellence for Smart Urban Governance (ALEXU-CoE-SUG). However, restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of ALEXU-CoE-SUG. For access to the data, please contact the corresponding author or ALEXU-CoE-SUG directly.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- UN-Habitat. Towards Arab Cities without Informal Areas: Analysis and Prospects; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Ndinda, C.; Hongoro, C. A Baseline Assessment for Future Impact Evaluation of Informal Settlements Targeted for Upgrading. Presented to Human Settlements Planning, Monitoring, and Evaluation. 2016. Available online: https://www.dhs.gov.za/sites/default/files/u19/A%20Baseline%20assessment%20for%20future%20impact%20evaluation%20of%20informal%20settlements%20targeted%20for%20upgrading.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- UN-Habitat. Streets as Tools for Urban Transformation in Slums: A Street-Led Approach to Citywide Slum Upgrading; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2014.

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, D. Understanding Cairo: The Logic of a City out of Control; The American University in Cairo Press: Cairo, Egypt, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Lughod, J.L. Urbanization in Egypt: Present State and Future Prospects. Economic Development and Cultural Change. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1965, 13, 313–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinkina, J.; Korotayev, A. Urbanization dynamics in Egypt: Factors, trends, perspectives. Arab Stud. Q. 2013, 35, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, A. Bridging the gap between theoretical exploration and practical application in urban informality: A critical review. J. Urban Manag. 2019, 8, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work. 2019. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/816281518818814423/main-report (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- African Research Universities Alliance. About ARUA. 2019. Available online: https://arua.org.za/about-arua/ (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Bhargava, V.; Cutler, K.; Ritchie, D. Stimulating the Demand for Good Governance; The Partnership for Transparency Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: https://ptfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/PTF-DFGG-Final-Report.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Mitlin, D.; Satterthwaite, D. Urban Poverty in the Global South: Scale and Nature; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A. Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2005, 71, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, A. Globalization and the politics of the informals in the global South. In Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia; Roy, A., AlSayyad, N., Eds.; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2004; pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, E. Regularization of Informal Settlements in Latin America; Policy Press, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, A. Deep democracy: Urban governmentality and the horizon of politics. Environ. Urban. 2001, 13, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. World Cities Report 2016: Urbanization and Development–Emerging Futures; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- Lombard, M. Constructing ordinary places: Place-making in urban informal settlements in Mexico. Prog. Plan. 2014, 94, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Auyero, J. From the client’s point(s) of view: How poor people perceive and evaluate political clientelism. Theory Soc. 1999, 28, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auyero, J. ‘This is a lot like the Bronx, isn’t it?’ Lived experiences of marginality in an Argentine slum. Am. Ethnol. 1999, 26, 898–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Batran, M.; Arandel, C. The Informal Housing Development Process in Egypt; Report prepared for Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique; CNRS: Pairs, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, C.O.N. Ordinary Families, Extraordinary Lives: Assets and Poverty Reduction in Guayaquil, 1978–2004; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt1280m1 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Simone, A. For the City Yet to Come: Changing African Life in Four Cities; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Robison, R. Global and world cities: A view from off the map. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2002, 26, 589–601. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard, M. Place-making and construction of informal settlements in Mexico. Rev. INVI 2015, 30, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A. Typology of informal housing in Egyptian cities: Taking account of diversity. International Development Planning Review 2002, 24, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Soto, H. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rakodi, C. A livelihoods approach–Conceptual issues and definitions. In Urban Livelihoods: A People-Centred Approach to Reducing Poverty; Rakodi, C., Lloyd-Jones, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Doe, J.; Roe, J. Grassroots engagement in urban upgrading: Beyond top-down interventions. J. Urban Dev. 2020, 45, 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. Planet of Slums; Verso: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, C.O.N. Urban Violence and Insecurity: An Introductory Roadmap. Environ. Urban. 2004, 16, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonyabancha, S. Land for housing the poor—By the poor: Experiences from the Baan Mankong nationwide slum upgrading programme in Thailand. Environ. Urban. 2009, 21, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonsiri, P. The Role of Community Participation in Low-Income Housing Program: A Case of Baan Mankong, Thailand; University of Erfurt: Erfurt, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R.; Potter, R.B. Doing Development Research; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, A. De Soto’s The mystery of capital: Reflections on the book’s public impact. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2012, 34, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. Le Droit a la Ville; Anthropos: Paris, France, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Retracking America: A Theory of Transactive Planning; Anchor Press: Harlow, UK, 1973; 289p. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Social Justic and the City; The University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.F.C. Housing by People: Towards Autonomy in Building Environments; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Streets as Public Spaces and Drivers of Urban Prosperity; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2013.