Renewable Energy in the Chinese News Media: A Comparative Study and Policy Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Development of Renewable Energy and Its Policies in China

3. Framing Renewable Energy in the News

4. Methodology

4.1. Media Selection and Sampling Method

4.2. Coding Schemes and Intercoder Reliability

5. Findings

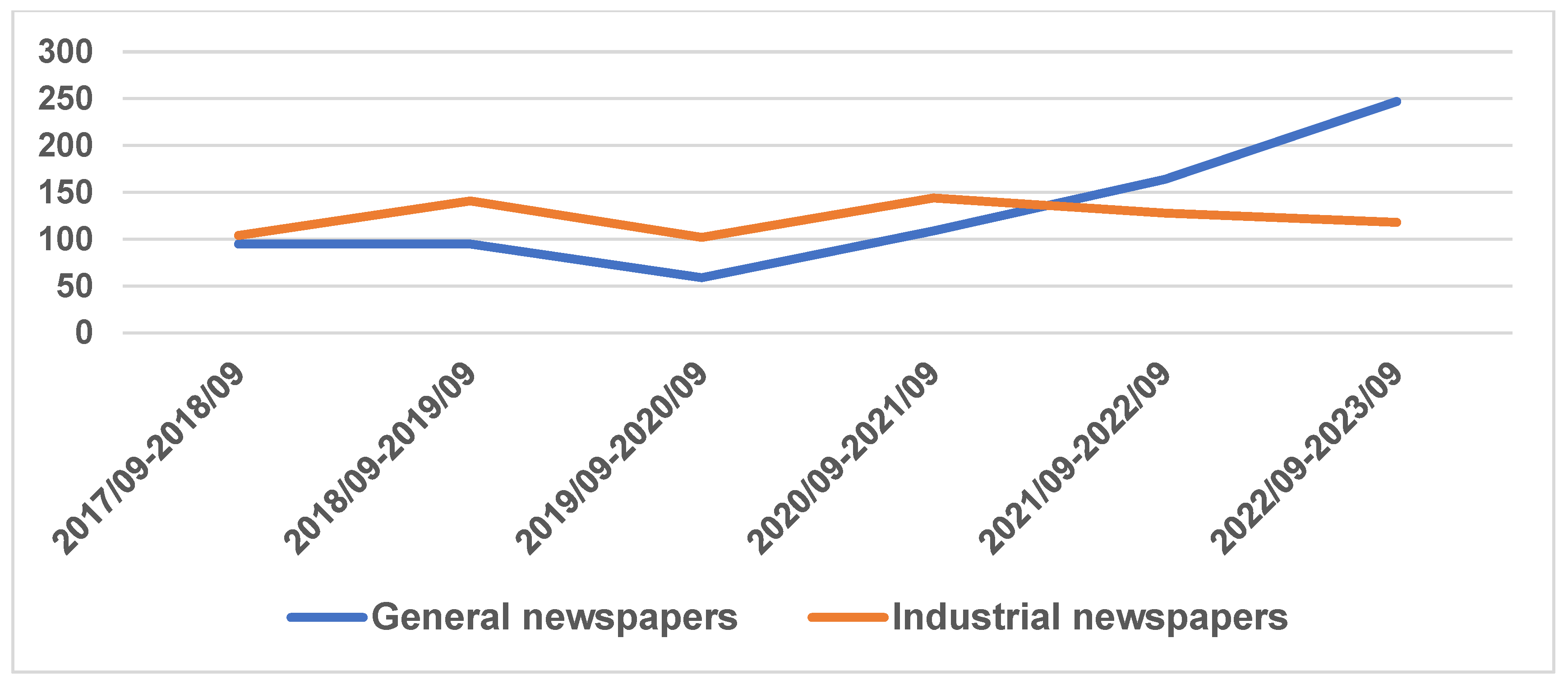

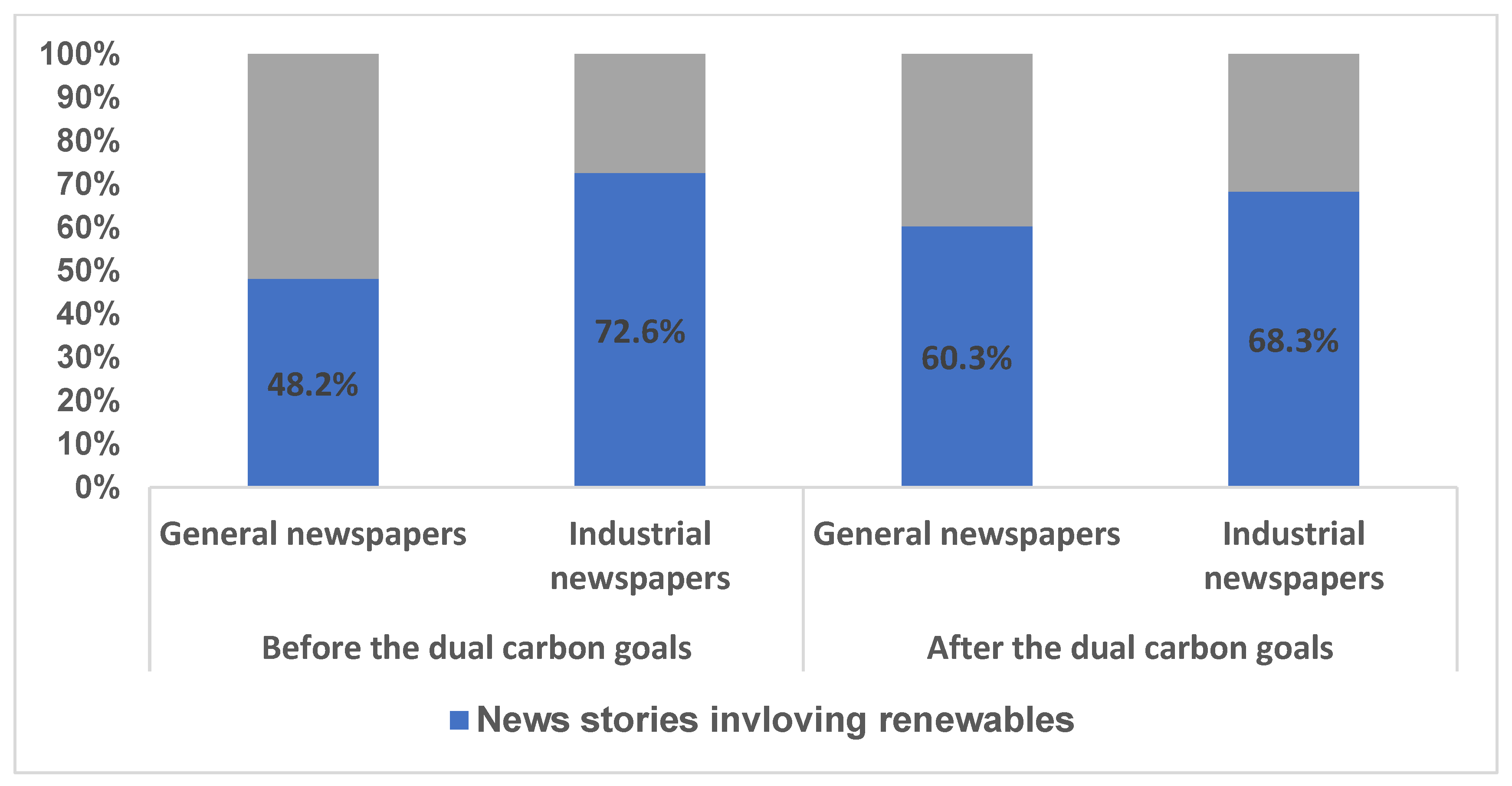

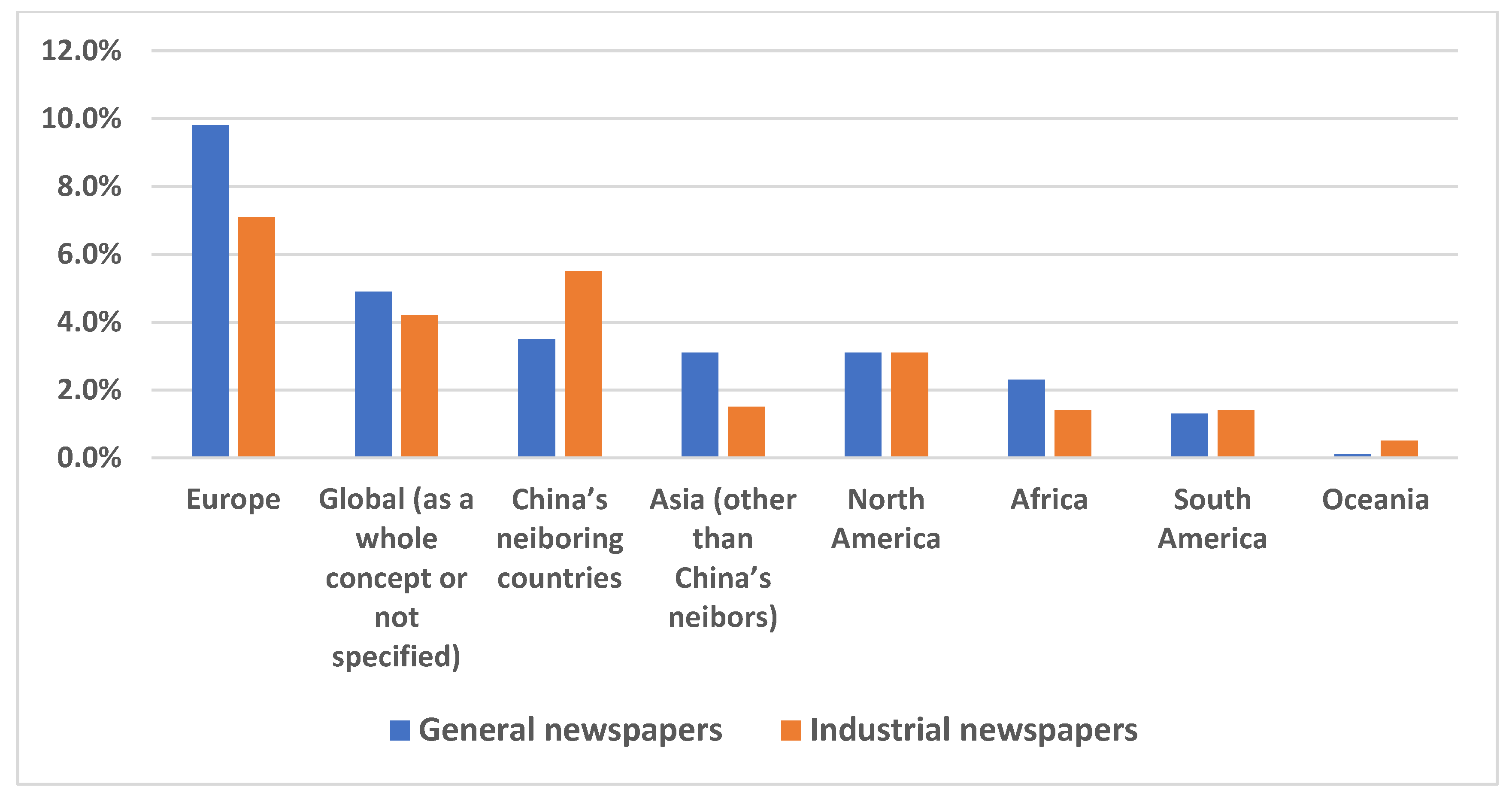

5.1. Nature of Coverage

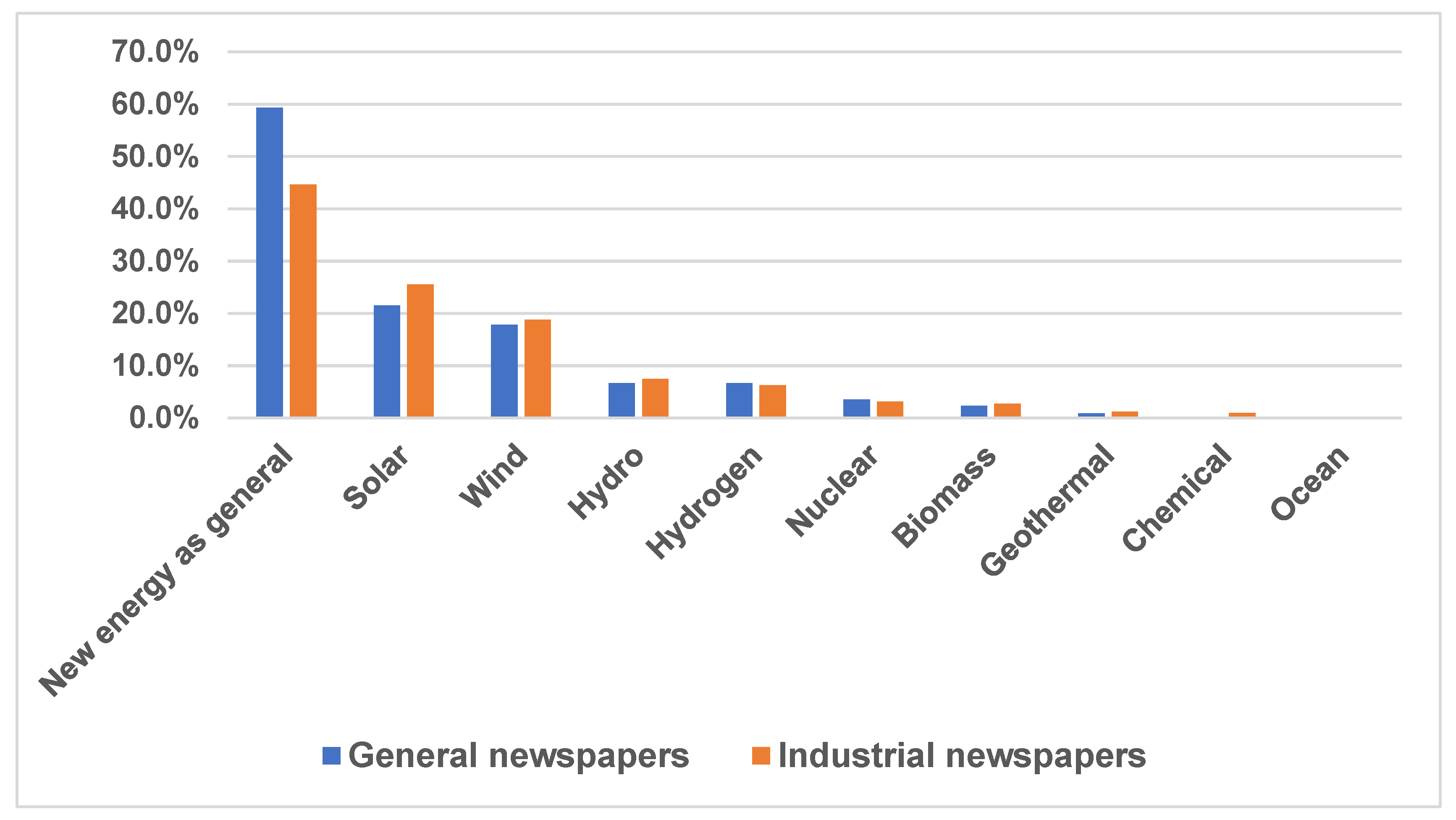

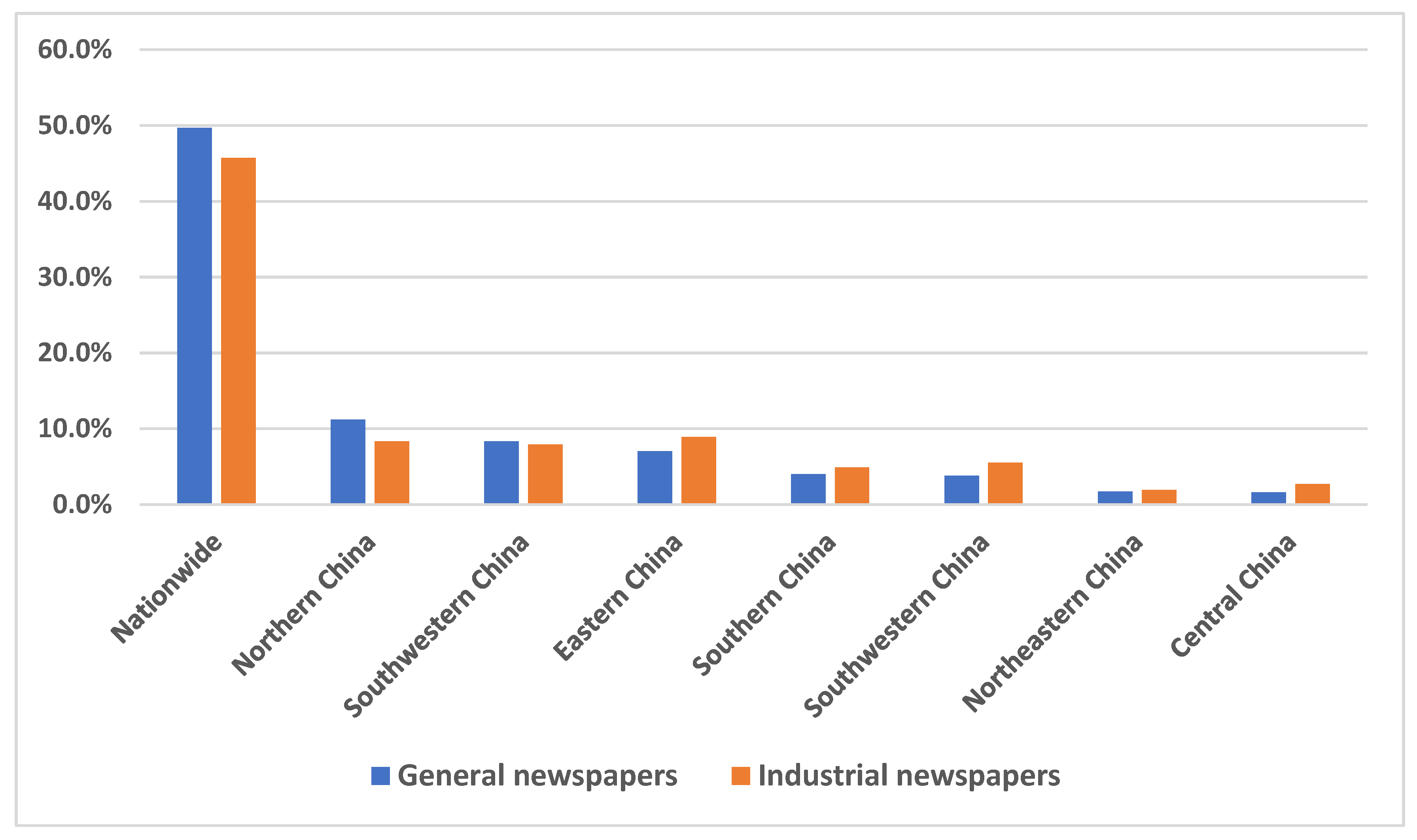

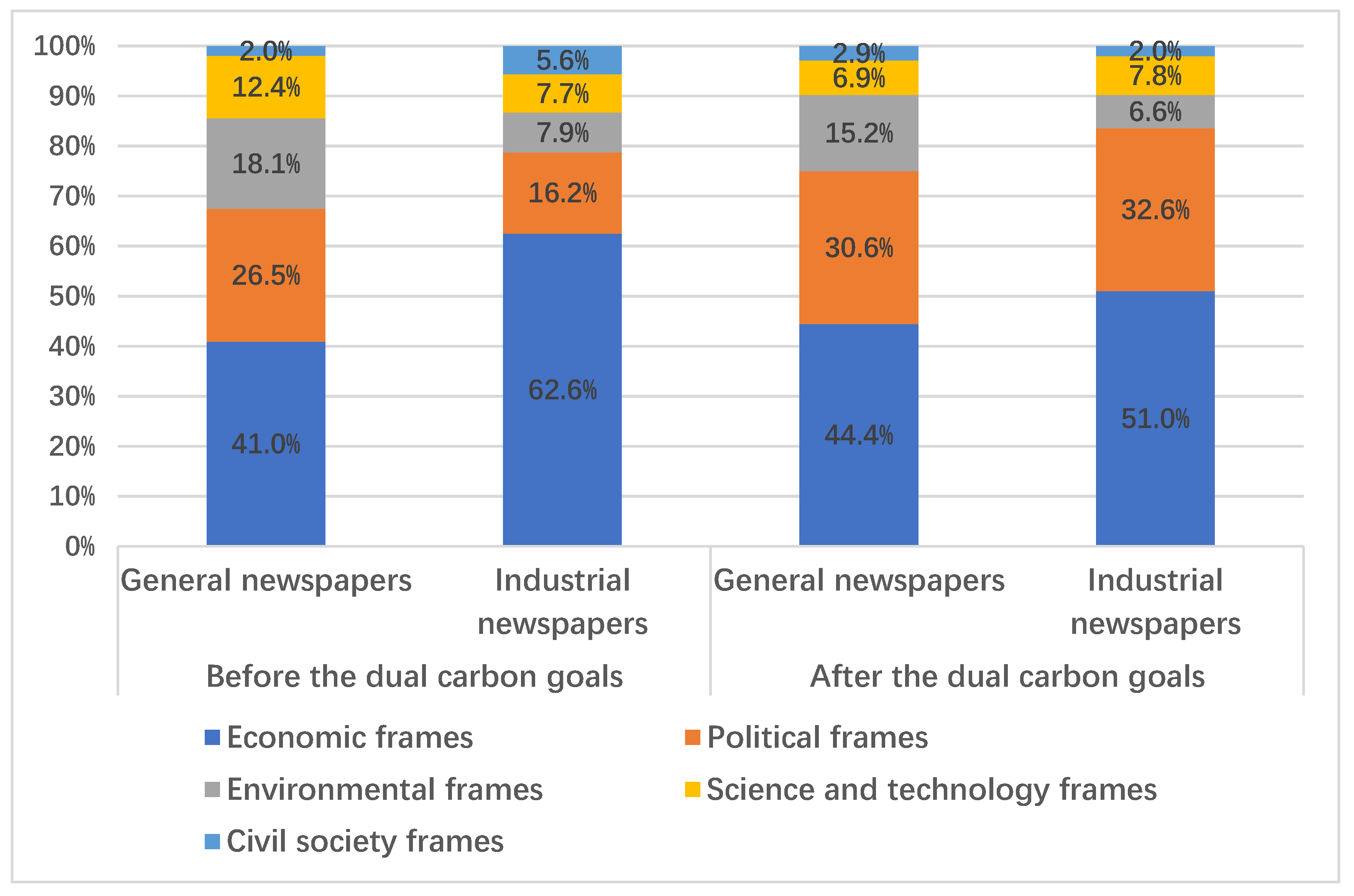

5.2. Dimensional Framing of New Energy and Renewables

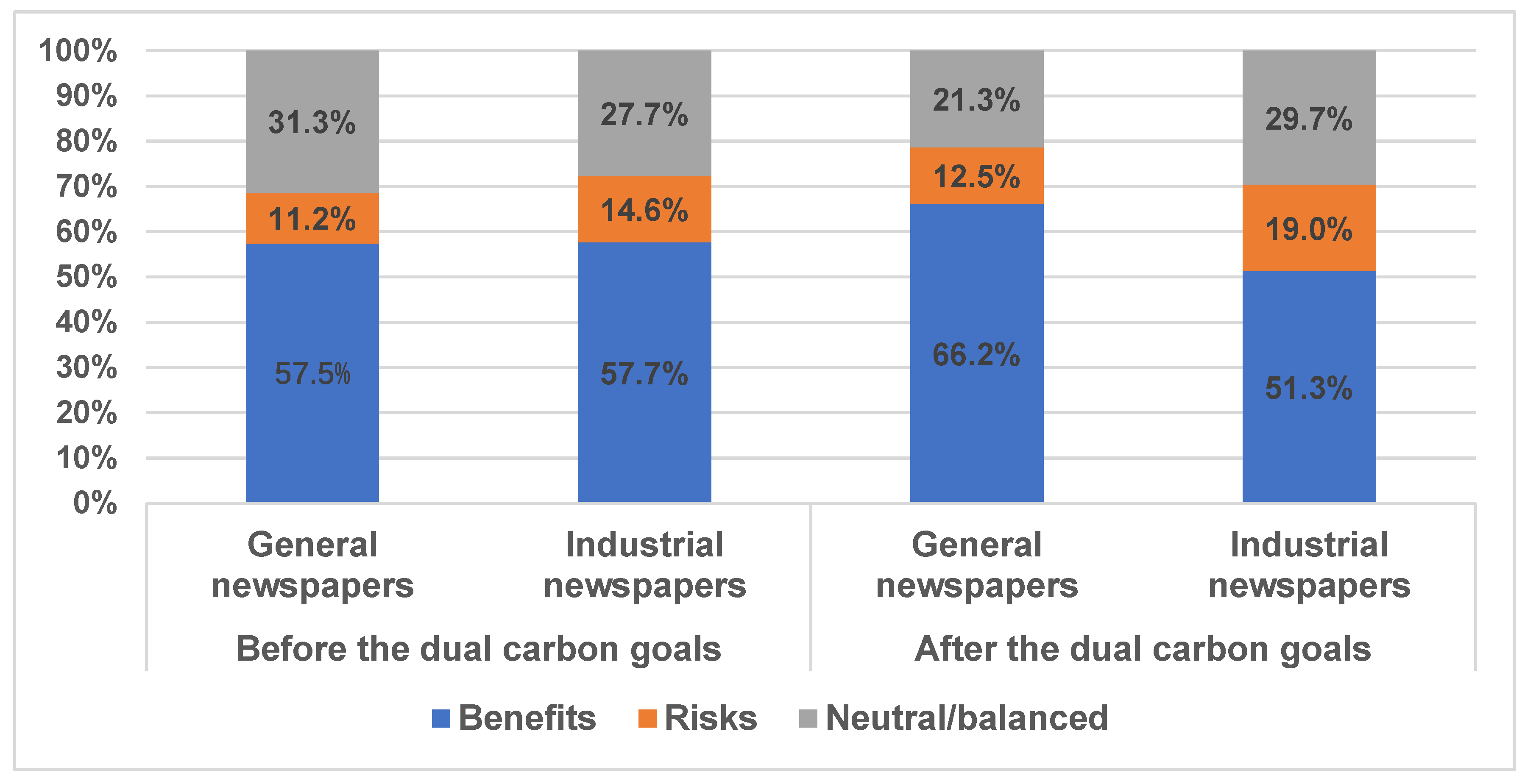

5.3. Risk and Benefit Framing of New Energy and Renewables

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China. Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Fully, Accurately, and Comprehensively Implementing the New Development Concept to Achieve Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-10/24/content_5644613.htm (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Amin, A.Z. Here Comes the Sun: Will China be a Superpower in a World Transformed by Renewable Energy? Newsweek, 12 January 2019; pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- BNEF. Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2019; Frankfurt School-UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance: Frankfurt, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, A.; Ingram, H. Social construction of target populations: Implications for politics and policy. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1993, 87, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M.; The Agenda-Setting Role of the Mass Media in the Shaping of Public Opinion. Mass Media Economics 2002 Conference, Held in London. 2002. Available online: http://sticerd.lse.ac.uk/dps/extra/McCombs.Pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Scheer, D. Communicating energy system modelling to the wider public: An analysis of German media coverage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Tong, Q.; Yu, S.; Wang, Y.; Chai, Q.; Zhang, X. Role of non-fossil energy in meeting China’s energy and climate target for 2020. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I.; Bilgili, F. Economic growth and biomass consumption nexus: Dynamic panel analysis for Sub-Sahara African countries. Appl. Energy 2015, 137, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuman, S.; Lin, A. China’s Renewable Energy Law and its impact on renewable power in China: Progress, challenges and recommendations for improving implementation. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China. Renewable Energy Law of China. Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of China. 2009. Available online: https://flk.npc.gov.cn/detail2.html?MmM5MDlmZGQ2NzhiZjE3OTAxNjc4YmY3MDhhNjA1NzM (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- China. The Medium- and Long-Term Renewable Energy Development Plan. National Energy Administration of China. 2007. Available online: https://www.nea.gov.cn/2007-09/05/c_131215784.htm?eqid=dd6bedaf00036c2e0000000364745c59 (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Ding, Y.; Kou, J. Non-fossil energy accounts for more than 15 percent of primary energy consumption. People’s Daily, 27 December 2020; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- China. Energy in China’s New Era. State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. 2020. Available online: http://www.scio.gov.cn/ztk/dtzt/42313/44537/index.htm?eqid=dc10f6380003713f00000005642b8929&eqid=e8e1a2da0010a94800000005649453aa (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- International Energy Agency. Executive summary of Renewables 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2023/executive-summary# (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Midttun, A.; Coulter, P.; Gadzekpo, A.; Wang, J. Comparing Media Framings of Climate Change in Developed, Rapid Growth and Developing Countries: Findings from Norway, China and Ghana. Energy Environ. 2015, 26, 1271–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Z.; Ximei, L.; Yulong, L.; Lilin, P. Review of renewable energy investment and financing in China: Status, mode, issues and countermeasures. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 31, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabré, M.M.; Gallagher, K.P.; Li, Z. Renewable energy: The trillion dollar opportunity for Chinese overseas investment. China World Econ. 2018, 26, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattich, T.; Freeman, D.; Scholten, D.; Yan, S. Renewable energy in EU-China relations: Policy interdependence and its geopolitical implications. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gippner, O.; Torney, D. Shifting policy priorities in EU-China energy relations: Implications for Chinese energy investments in Europe. Energy Policy 2017, 101, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuortimo, K.; Härkönen, J.; Karvonen, E. Exploring the global media image of solar power. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2806–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Raza, M.Y. Research on China’s renewable energy policies under the dual carbon goals: A political discourse analysis. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 48, 101118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Hua, X.; Ren, P. Is the tone of the government-controlled media valuable for capital market? Evidence from China’s new energy industry. Energy Policy 2024, 184, 113917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Tahvanainen, L.; Ahponen, P.; Pelkonen, P. Bio-energy in China: Content analysis of news articles on Chinese professional internet platforms. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 2300–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Gu, J.; Xu, S. Environmental beliefs and public acceptance of nuclear energy in China: A moderated mediation analysis. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.S.; Kristiansen, S. Environmental Debates over Nuclear Energy: Media, Communication, and the Public. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerner, C.L. Media, fear, and nuclear energy: A case study. Soc. Sci. J. 2014, 51, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Han, Z. The framing of nuclear energy in Chinese media discourse: A comparison between national and local newspapers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, M.M. Newspapers use three frames to cover alternative energy. Newsp. Res. J. 2010, 31, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjølsvold, T.M. Curb your enthusiasm: On media communication of bioenergy and the role of the news media in technology diffusion. Environ. Commun. 2012, 6, 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.J.; Wang, W.; Pinto, J. Beyond disaster and risk: Post-Fukushima nuclear news in U.S. and German press. Commun. Crit. Cult. Stud. 2016, 9, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djerf-Pierre, M.; Cokley, J.; Kuchel, L.J. Framing Renewable Energy: A Comparative Study of Newspapers in Australia and Sweden. Environ. Commun. 2016, 10, 634–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.C.; Rand, G.M.; Melnick, L.L. Wind energy in US media: A comparative state-level analysis of a critical climate change mitigation technology. Environ. Commun. 2009, 3, 168–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L.; Poortinga, W. Values, Perceived Risks and Benefits, and Acceptability of Nuclear Energy. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.S.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, B.W. Public’s perception and judgment on nuclear power. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2000, 27, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, D.; Wolling, J. Fukushima effects in Germany? Changes in media coverage and public opinion on nuclear power. Public Underst. Sci. 2016, 25, 842–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, S.; Bonfadelli, H.; Kovic, M. Risk perception of nuclear energy after Fukushima: Stability and change in public opinion in Switzerland. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2016, 30, 24–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.E.; Hart, P.S.; Schuldt, J.P.; Evensen, D.T.N.; Boudet, H.S.; Jacquet, J.B.; Stedman, R.C. Public opinion on energy development: The interplay of issue framing, top-of-mind associations, and political ideology. Energy Policy 2015, 81, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Li, J. Media coverage and government policy of nuclear power in the People’s Republic of China. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2014, 77, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, W. Policy-Driven, National Development and Environmental Protection: A Study on the New Energy Vehicle Communication. Sci. Sci. Manag. S T 2023, 44, 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cnenergynews Website. About Us. 2023. Available online: https://www.cnenergynews.cn/about.html (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development 2017. 2018. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1899855.html (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202402/t20240228_1947915.html (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Yu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Li, L. A comprehensive evaluation of the development and utilization of China’s regional renewable energy. Energy Policy 2019, 127, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Energy Administration of China. 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of Renewable Energy. 2021. Available online: http://zfxxgk.nea.gov.cn/1310611148_16541341407541n.pdf?eqid=f39ccaf9002c5e4800000002643d53e7 (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- National Energy Administration of China. Notification on the Monitoring and Evaluation Results of National Renewable Energy Power Development in 2022 by the National Energy Administration. 2023. Available online: http://zfxxgk.nea.gov.cn/2023-09/07/c_1310741874.htm (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Dong, Z. Europe and America’s green transition meets its plight. China Energy News, 29 August 2022; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal: Striving to Be the First Climate-Neutral Continent. 2019. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Wang, L. Controversy over EU’s push for Green New Deal. China Energy News, 12 December 2019; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X. Going or staying with nuclear power in Europe in light of the energy crisis. Guangming Daily, 6 September 2022; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z. Household photovoltaic continues to be hot. China Energy News, 29 March 2021; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H. The central government and the local government play a strong voice of clean energy development, and the First Engineering Bureau of China Water Conservancy and Hydropower Corporation (CEB) plays to its technical advantages. Economic Daily, 12 September 2023; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- An, N. Promote clean and low-carbon energy consumption in the building materials industry. China Energy News, 14 November 2022; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. Yunnan releases carbon peaking implementation plan. China Energy News, 22 May 2023; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K. National carbon market opens, green and low-carbon development becomes “real money”. Guangming Daily, 25 July 2021; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. The carbon market will enter a period of smooth operation in the “14th Five-Year Plan”. China Energy News, 9 November 2020; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Xu, S. Green transition is not easy while uncertainty remains—World energy situation outlook 2023. Guangming Daily, 12 January 2023; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Ye, H.; Liu, Q. The beautiful countryside plays “fishing song”. China Energy News, 12 December 2018; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K. People rely on wind power and photovoltaic power. Guangming Daily, 7 August 2023; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. How old coal mining areas get a new lease on life. Economic Daily, 20 July 2023; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y. Gathering strong new kinetic energy for high-quality development. Guangming Daily, 18 April 2023; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, P. Public Attitude and Opinion Leaders: Mapping Chinese Discussion of EU’s Energy Role on Social Media. JCMS-J. Common Mark. Stud. 2022, 60, 1777–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zhu, L.; Zeng, J. Analysis on the impact of media attention on energy enterprises and energy transformation in China. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 1820–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Before the Dual Carbon Goals | After the Dual Carbon Goals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Newspapers | Industrial Newspapers | General Newspapers | Industrial Newspapers | |

| 1 | energy | energy | energy | energy |

| 2 | development | development | development | development |

| 3 | new energy | project | green | project |

| 4 | vehicles | China | China | new energy |

| 5 | technology | technology | industry | China |

| 6 | industry | electricity | technology | technology |

| 7 | China | market | construction | electricity |

| 8 | construction | company | new energy | market |

| 9 | enterprise | enterprise | implement | enterprise |

| 10 | project | construction | our country | construction |

| 11 | national | new energy | national | industry |

| 12 | clean | photovoltaic | ecology | implement |

| 13 | innovation | implement | promote | power grid |

| 14 | economy | power grid | boost | company |

| 15 | our country | industry | economy | our country |

| General Newspapers (X2 = 61.59, df = 8, p < 0.001) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Frames | Political Frames | Environmental Frames | Science and Technological Frames | Civil Society Frames | |

| Risks | 6.7% | 3.7% | 0.9% | 0.5% | 0.3% |

| Benefits | 21.7% | 20.7% | 13.7% | 5.2% | 2.0% |

| Neutral/balanced | 14.7% | 5.0% | 1.6% | 3.0% | 0.4% |

| Industrial Newspapers (X2 = 60.5, df = 8, p < 0.001) | |||||

| Economic Frames | Political Frames | Environmental Frames | Science and Technological Frames | Civil Society Frames | |

| Risks | 9.8% | 4.9% | 1.4% | 0.5% | 0.1% |

| Benefits | 25.9% | 14.2% | 5.7% | 5.4% | 3.4% |

| Neutral/balanced | 21.4% | 4.7% | 0.3% | 1.8% | 0.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Peng, X. Renewable Energy in the Chinese News Media: A Comparative Study and Policy Implications. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16125237

Zhang L, Peng X. Renewable Energy in the Chinese News Media: A Comparative Study and Policy Implications. Sustainability. 2024; 16(12):5237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16125237

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Li, and Xinyi Peng. 2024. "Renewable Energy in the Chinese News Media: A Comparative Study and Policy Implications" Sustainability 16, no. 12: 5237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16125237

APA StyleZhang, L., & Peng, X. (2024). Renewable Energy in the Chinese News Media: A Comparative Study and Policy Implications. Sustainability, 16(12), 5237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16125237