The Impact of Social Capital on Migrants’ Social Integration: Evidence from China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

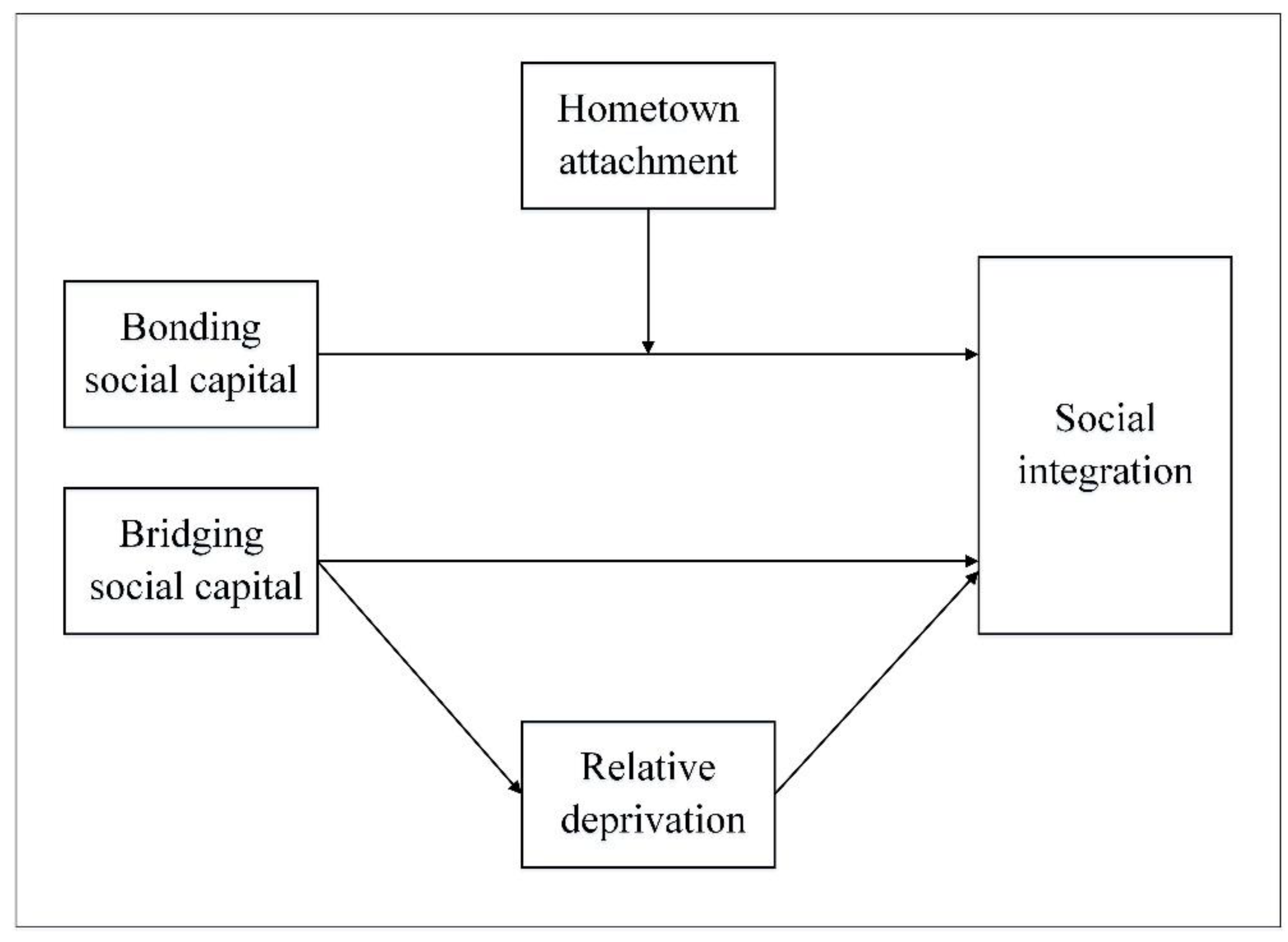

2.1. Social Capital and Social Integration

2.2. The Mediating Effect of Relative Deprivation

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Hometown Attachment

3. Methods and Variables

3.1. Methods

3.2. Variables and Measurement

3.2.1. Social Integration

3.2.2. Social Capital

3.2.3. Relative Deprivation

3.2.4. Hometown Attachment

3.2.5. Covariates

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Factor Analysis

4.3. Analysis of Main Effects

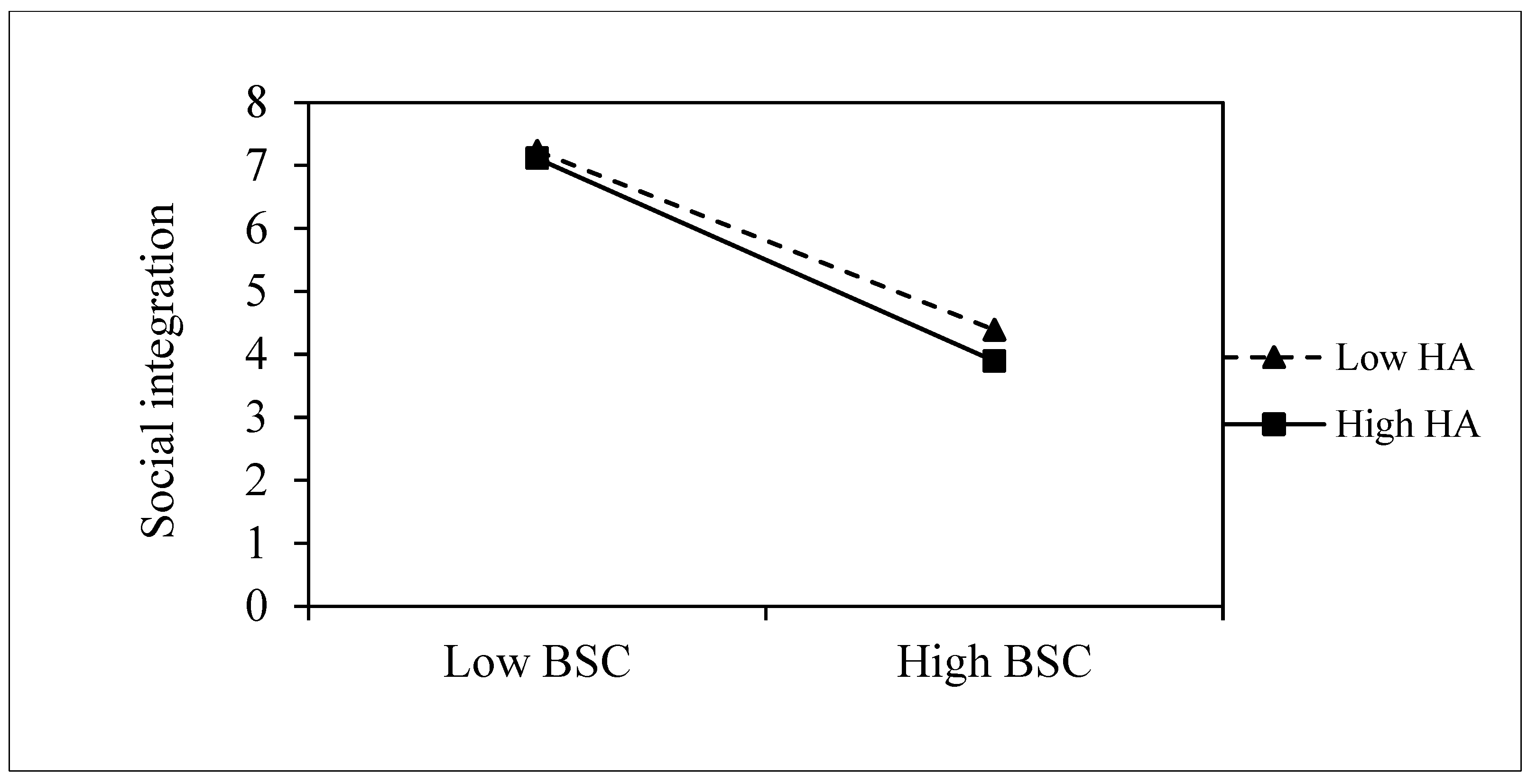

4.4. Mediation and Moderation Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tacoli, C. The Links between Migration, Globalization and Sustainable Development. In Survival for a Small Planet; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 200–206. [Google Scholar]

- NBS. The Seventh National Population Census Bulletin (No. 7); National Bureau of Statistics of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Chen, C.; Fan, C.C. Rural-Urban Circularity in China: Analysis of Longitudinal Surveys in Anhui, 1980–2009. Geoforum 2018, 93, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, L.; Erel, U.; D’Angelo, A. Introduction Understanding ‘Migrant Capital’. In Migrant Capital: Networks, Identities and Strategies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlbeck, Ö.; Fortelius, S. The Utilisation of Migrant Capital to Access the Labour Market: The Case of Swedish Migrants in Helsinki. Soc. Incl. 2019, 7, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ruan, D.; Lai, G. Social Capital and Economic Integration of Migrants in Urban China. Soc. Netw. 2013, 35, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grootaert, C.; Van Bastelaer, T. Understanding and Measuring Social Capital; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 1–320. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. The Impact of Social Structure on Economic Outcomes; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; Volume 19, ISBN 0-521-52167-X. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, R.; Li, T. Localized Social Capital and Social Integration of Migrants in Urban China. Popul. Res. 2012, 36, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Garip, F. Social Capital and Migration: How Do Similar Resources Lead to Divergent Outcomes? Demography 2008, 45, 591–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-7432-0304-6. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.; Landolt, P. Social Capital: Promise and Pitfalls of Its Role in Development. J. Lat. Am. Stud. 2000, 32, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social Capital: It’s Origins and Applications in Contemporary Society. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Logan, J.R. In and out of Chinatown: Residential Mobility and Segregation of New York City’s Chinese. Soc. Forces 1991, 70, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ruan, J. Cultural Diversity, Social Network, and off-Farm Employment: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 89, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Wen, M.; Wang, G. Social Capital and Work among Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China. Asian Popul. Stud. 2011, 7, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, H.; Yasunobu, K. What Is Social Capital? A Comprehensive Review of the Concept. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2009, 37, 480–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenzie, K. Urbanization, Social Capital and Mental Health. Glob. Soc. Policy 2008, 8, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, A.; Li, Y.; Al-Ansari, M.M.H.; Le, K.T. Social Capital and Citizens’ Attitudes towards Migrant Workers. Soc. Incl. 2017, 5, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Démurger, S.; Gurgand, M.; Li, S.; Yue, X. Migrants as Second-Class Workers in Urban China? A Decomposition Analysis. J. Comp. Econ. 2009, 37, 610–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P. Subcultural Conflict and Working-Class Community. In Culture, Media, Language; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- De Haas, H. The Internal Dynamics of Migration Processes: A Theoretical Inquiry. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2010, 36, 1587–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patulny, R.V.; Lind Haase Svendsen, G. Exploring the Social Capital Grid: Bonding, Bridging, Qualitative, Quantitative. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2007, 27, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, K. Labour Market Participation: The Influence of Social Capital. Labour Mark. Trends 2005, 3, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lancee, B. Immigrant Performance in the Labour Market: Bonding and Bridging Social Capital; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 90-8964-357-5. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, L.; Pilati, K. The Role of Social Capital in Migrants’ Engagement in Local Politics in European Cities. In Social Capital, Political Participation and Migration in Europe: Making Multicultural Democracy Work? Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 87–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.; Selden, M. The Origins and Social Consequences of China’s Hukou System. China Q. 1994, 139, 644–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runciman, W.G. Relative Deprivation and Social Justice: A Study of Attitudes to Social Inequality in Twentieth-Century England; Penguin: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.E.; Frijters, P.; Shields, M.A. Relative Income, Happiness, and Utility: An Explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and Other Puzzles. J. Econ. Lit. 2008, 46, 95–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, A.; Kosaka, K.; Hamada, H. A Paradox of Economic Growth and Relative Deprivation. J. Math. Sociol. 2014, 38, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Hakim, R.; Abdul-Razak, N.A.; Ismail, R. Does Social Capital Reduce Poverty? A Case Study of Rural Households in Terengganu, Malaysia. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 14, 556–566. [Google Scholar]

- Tenzin, G.; Otsuka, K.; Natsuda, K. Can Social Capital Reduce Poverty? A Study of Rural Households in Eastern B Hutan. Asian Econ. J. 2015, 29, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Paudel, K.P.; Li, G.; Lei, M. Income Inequality among Minority Farmers in China: Does Social Capital Have a Role? Rev. Dev. Econ. 2019, 23, 528–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imlach Gunasekara, F.; Carter, K.N.; Crampton, P.; Blakely, T. Income and Individual Deprivation as Predictors of Health over Time. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eibner, C.; Evans, W.N. Relative Deprivation, Poor Health Habits, and Mortality. J. Hum. Resour. 2005, 40, 591–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koktsidis, P.I. From Deprivation to Violence? Examining the Violent Escalation of Conflict in the Republic of Macedonia. Dyn. Asymmetric Confl. 2014, 7, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Xiao, L.; Ye, Y. Relative Deprivation and Prosocial Tendencies in Chinese Migrant Children: Testing an Integrated Model of Perceived Social Support and Group Identity. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 658007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, F. Economic Disadvantages and Migrants’ Subjective Well-being in China: The Mediating Effects of Relative Deprivation and Neighbourhood Deprivation. Popul. Space Place 2019, 25, e2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishbeth, C.; Powell, M. Place Attachment and Memory: Landscapes of Belonging as Experienced Post-Migration. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, P. Exploring the Relationship between Place Attachment and Mobility; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H. Place Attachment and Belonging among Educated Young Migrants and Returnees: The Case of Chaohu, China. Popul. Space Place 2017, 23, e1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R.M. Settlement-Identity: Psychological Bonds with Home Places in a Mobile Society. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 183–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Huang, J.Z.; Hu, J. Sparse Logistic Principal Components Analysis for Binary Data. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2010, 4, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, M. Structural Equation Modeling Using Stata. J. Behav. Data Sci. 2021, 1, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.M. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1964; ISBN 0-19-500896-0. [Google Scholar]

- Entzinger, H.; Biezeveld, R. Benchmarking in Immigrant Integration; Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Novakowski, D. Personal Relative Deprivation and Risk: An Examination of Individual Differences in Personality, Attitudes, and Behavioral Outcomes. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 90, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitzhaki, S. Relative Deprivation and the Gini Coefficient. Q. J. Econ. 1979, 93, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakwani, N. The Relative Deprivation Curve and Its Applications. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1984, 2, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podder, N. Relative Deprivation, Envy and Economic Inequality. Kyklos 1996, 49, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, L. Upper Boundedness for the Measurement of Relative Deprivation. Rev. Income Wealth 2010, 56, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittelson, W.H. Environmental Perception and Urban Experience. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ye, R.; Lin, S. Beyond Destinations: Environmental Perception and Village Attachment among Stayers, Outmigrants and Returnees in Rural China. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, e2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Cao, Q. The Effects of Social Participation on Social Integration. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 919592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paola, M.; Brunello, G. Education as a Tool for the Economic Integration of Migrants; IZA—Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.C. Social Networks. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1974, 3, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited. Sociol. Theory 1983, 1, 201–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahinden, J. Cities, Migrant Incorporation, and Ethnicity: A Network Perspective on Boundary Work. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2013, 14, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannestad, P.; Lind Haase Svendsen, G.; Tinggaard Svendsen, G. Bridge over Troubled Water? Migration and Social Capital. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2008, 34, 607–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Building a Network Theory of Social Capital. In Social Capital; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2017; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital; Readings in Economic Sociology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, H.; Hickman, M.J. Migration, Postindustrialism and the Globalized Nation State: Social Capital and Social Cohesion Re-Examined. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2008, 31, 1222–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R. Benefit or Burden? Social Capital, Gender, and the Economic Adaptation of Refugees. Int. Migr. Rev. 2009, 43, 332–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verba, S.; Nie, N.H.; Kim, J. Participation and Political Equality: A Seven-Nation Comparison; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1978; ISBN 0-521-21905-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, P.M. Generating Social Capital for Bridging Ethnic Divisions in the Balkans: Case Studies of Two Bosniak Cities. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2006, 29, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlander, S. The Importance of Different Forms of Social Capital for Health. Acta Sociol. 2007, 50, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunguang, W.; Wen, L. Social Integration of China’s Floating Population; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y. Household Migration, Social Support, and Psychosocial Health: The Perspective from Migrant-Sending Areas. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Meng, T. Bonding, Bridging, and Linking Social Capital and Self-Rated Health among Chinese Adults: Use of the Anchoring Vignettes Technique. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnitsch, K.; Flora, J.; Ryan, V. Bonding and Bridging Social Capital: The Interactive Effects on Community Action. Community Dev. 2006, 37, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarko, A.; Berry, J.W.; Choi, K. Social Capital, Acculturation Attitudes, and Sociocultural Adaptation of Migrants from Central Asian Republics and South Korea in Russia. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 23, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos, J.-Y.; Grégoire, P. Absolute and Relative Deprivation and the Measurement of Poverty. Rev. Income Wealth 2002, 48, 471–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlinghagen, M.; Kern, C.; Stein, P. Migration, Social Stratification and Dynamic Effects on Subjective Well Being. Adv. Life Course Res. 2021, 48, 100393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, P.R. The Protest Intentions of Skilled Immigrants with Credentialing Problems: A Test of a Model Integrating Relative Deprivation Theory with Social Identity Theory. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Strijker, D.; Wu, Q. Place Identity: How Far Have We Come in Exploring Its Meanings? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 503569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adger, W.N.; Boyd, E.; Fábos, A.; Fransen, S.; Jolivet, D.; Neville, G.; de Campos, R.S.; Vijge, M.J. Migration Transforms the Conditions for the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e440–e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y. The Impact of Urban Public Services on the Residence Intentions of Migrant Entrepreneurs in the Western Region of China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Specifications | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female = 0, male = 1 | 0.52 | 0.50 |

| Age | ≥15 years old | 36.66 | 11.07 |

| Marital status | Unmarried = 0, married = 1 | 0.81 | 0.39 |

| Education level | 1–7 | 3.44 | 1.16 |

| Variable | Items | Loadings | CR | AVE | Correlation Coefficient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | Housing expenditure | 0.772 | 0.879 | 0.709 | 0.842 | 0.431–0.703 |

| Total expenditure | 0.904 | |||||

| Total income | 0.845 | |||||

| CI | Social exclusion | 0.708 | 0.754 | 0.506 | 0.711 | 0.209–0.371 |

| Customs and traditions | 0.677 | |||||

| Hygiene habits | 0.747 | |||||

| BI | Community involvement | 0.814 | 0.757 | 0.519 | 0.720 | 0.211–0.433 |

| Political participation | 0.797 | |||||

| Volunteer participation | 0.510 | |||||

| PI | Favorability | 0.861 | 0.883 | 0.716 | 0.846 | 0.579–0.635 |

| Attention | 0.856 | |||||

| Willingness to integrate | 0.820 | |||||

| BSC | Trade union | 0.704 | 0.753 | 0.606 | 0.778 | 0.332 |

| Volunteer association | 0.846 | |||||

| BRC | Alumni association | 0.500 | 0.749 | 0.523 | 0.723 | 0.141–0.315 |

| Fellow townsmen association | 0.996 | |||||

| Hometown chamber of commerce | 0.572 |

| Variable | Total | By Dimensions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |

| SI | EI | CI | BI | PI | |

| Gender | −0.016 | −0.040 ** | −0.636 *** | 0.819 *** | −0.339 *** |

| (0.015) | (0.009) | (0.066) | (0.040) | (0.068) | |

| Age | 0.023 *** | −0.0003 | 0.011 ** | 0.034 *** | 0.128 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.0004) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| Marital status | 0.822 *** | 0.455 *** | 1.898 *** | 0.624 *** | 0.778 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.004) | (0.031) | (0.019) | (0.032) | |

| Education level | 1.128 *** | 0.965 *** | −0.379 *** | 0.201 *** | 1.532 *** |

| (0.020) | (0.012) | (0.089) | (0.053) | (0.092) | |

| BSC | −0.089 *** | −0.036 *** | 0.031 *** | −0.223 *** | −0.163 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.010) | (0.006) | (0.010) | |

| BRC | 0.147 *** | 0.034 *** | 0.048 *** | 0.454 *** | 0.293 |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.011) | (0.007) | (0.011) | |

| _cons | 9.045 *** | 2.725 *** | 50.677 *** | 9.373 *** | 66.778 *** |

| (0.051) | (0.030) | (0.231) | (0.139) | (0.237) | |

| F | 4899.471 *** | 3394.660 *** | 959.236 *** | 2468.519 *** | 615.419 *** |

| R2 | 0.147 | 0.107 | 0.032 | 0.080 | 0.021 |

| Structural Path | Path Coefficient | S.E. | p-Values | Confidence Intervals (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI ← BSC | −0.224 | 0.006 | <0.001 | −0.236–0.212 |

| SI ← BRC | 0.361 | 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.349–0.372 |

| RD ← BRC | −0.018 | 0.002 | <0.001 | −0.023–0.013 |

| SI ← RD | −0.210 | 0.002 | <0.001 | −0.215–0.206 |

| SI ← BSC*HA | −0.011 | 0.002 | <0.001 | −0.015–0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Huang, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, G. The Impact of Social Capital on Migrants’ Social Integration: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135564

Zhang X, Lu X, Huang C, Liu W, Wang G. The Impact of Social Capital on Migrants’ Social Integration: Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2024; 16(13):5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135564

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xin, Xudong Lu, Chunjie Huang, Wenbo Liu, and Guangchen Wang. 2024. "The Impact of Social Capital on Migrants’ Social Integration: Evidence from China" Sustainability 16, no. 13: 5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135564