1. Introduction

In the pursuit of global sustainability, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) serve as a beacon, guiding collective efforts towards a more equitable, prosperous, and environmentally sound future. Universities play a crucial role in this regard by supporting knowledge generation, dissemination, and societal engagement [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Within the Arab region, universities have a significant influence, serving not only as centers of higher learning but also as vital contributors to regional development agendas. However, while the importance of universities in advancing sustainable development is widely recognized, a comprehensive understanding of their specific roles and contributions within the Arab context remains relatively underexplored. Against this backdrop, this study examined on a scholarly basis the multifaceted engagement of universities in the Arab region with the SDGs. The inquiry was motivated by the need to clarify how universities can effectively support and accelerate the achievement of the SDGs, thereby strengthening the effectiveness of multi-sectoral partnerships at the national level. At the core of the study lies an exploration of four pivotal functional areas of universities: institutional capacity and governance, university–community partnerships and collaboration, research productivity, and teaching and learning. Through meticulous examination of the practices and strategies deployed within these functional domains, our research sought to uncover the mechanisms by which universities contribute to the advancement of the SDGs. We recognize that universities play a dual role as both agents of change and beneficiaries of sustainable development initiatives. Understanding the complex interplay between university activities and sustainable development outcomes is essential for planning well-informed policies and strategies aimed at fostering harmonious partnerships between academia, government, and civil society. This study aimed to move beyond simply documenting university contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by conducting a comparative analysis to identify similarities and differences among universities in the Arab region. Such analysis holds the promise of providing valuable insights into the contextual factors that shape university engagement with sustainable development goals, leading to the design of appropriate interventions and best practices to enhance their effectiveness. Guided by two overarching research questions, this study sought to advance scholarly discourse on the relationship between universities and sustainable development in the Arab region. Through rigorous empirical investigation and theoretical analysis, the study aimed to offer evidence-based recommendations for maximizing the transformative potential of universities as drivers of sustainable development in the Arab world.

The rate of progress towards achieving all of these goals is not as fast as expected, as many SDG indicators and targets are still off-track [

5,

6,

7]. According to the 2023 UN Sustainable Development Progress Report, only 15% of the SDGs are on track, progress on more than 50% of targets is weak and insufficient, and 30% have stalled or reserved. In general, there is a large body of research demonstrating that numerous challenges have impeded the successful implementation of SDGs in many countries worldwide. These challenges include but are not limited to the lack of multi-stakeholders engagement, unclear policy guidelines [

8], the escalating impacts of climate change [

9], ineffective governance structures and lack of political commitment [

10], disagreements on local priorities [

11], lack of integration, and difficulties of measurement [

12]. It is also worth noting that the implementation of the SDGs to date shows significant gaps, especially with respect to measuring countries’ performance and progress towards achieving all these goals [

13,

14,

15]. To address these challenges, it is imperative that all UN Member States should urgently prioritize the integration of the SDGs into national policies, strategies, plans, and public investments. Particular emphasis should be placed on leveraging the power of cross-sectoral and multi-stakeholder partnerships and collaboration to reduce the SDGs implementation gaps. Diverse government institutions, civil society organizations, academia, and private sector partners should be involved to take on significant roles in the SDG implementation framework. Within this context of partnership, higher education institutions (HEIs) are expected to play a leading role in accelerating the achievement of the 17 SDGs [

16,

17,

18,

19].

The current study aims to explore the essential role of universities in the Arab region in fostering and accelerating the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It seeks to enhance the effectiveness of multi-sectoral partnerships at the national level, particularly in terms of monitoring, evaluating, and reporting progress towards the SDGs. The research will focus on four key functional domains of universities: institutional capacity and governance, university–community partnerships and collaboration, research productivity, and teaching and learning. By examining practices within each of these areas, the study aims to assess their potential contributions to advancing the SDGs. Additionally, it will evaluate the similarities and differences in how universities in the region contribute to the SDGs. Guided by two fundamental research questions, the study aims to provide insights into the mechanisms through which universities can act as catalysts for sustainable development within their respective contexts.

There are two main pathways of involvement through which the higher education sector impacts the SDG framework [

12,

18,

20]. First, the importance of higher education to the SDGs is explicitly formulated as a stand-alone education goal under SDG4 (Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all) and education-related targets among other goals. There are two targets under SDG4 that are closely related to higher education, namely target 4.3 and target 4.b. Target 4.3 specifically states, “By 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university”. Target 4.b was developed as a necessary implementation measure of target 4.3, which aims to increase the number of scholarships and to expand accessibility of higher education [

21]. Second, the higher education sector has been recognized as an influential driver for implementing the full set of the 17 SDGs not just for its educational role. For instance, higher education institutions, particularly universities, can significantly contribute to the realization of all the SDGs by providing the necessary cutting-edge academic knowledge in both teaching and research and the evidence-based solutions and innovations required to address the SDGs implementation challenges [

12,

22,

23]. Furthermore, a wide range of functional areas has been identified by SDSN through which higher education institutions can contribute towards the achievement of the SDGs. These areas include institutional capacity and governance, university–community partnerships, research and development, and teaching and learning [

20].

In general, there is a growing global recognition among policymakers and academics of the need to incentivize higher education institutions to take on a leading role in the multi-sectoral partnership efforts required for the successful implementation of the SDGs. UNESCO has been at the forefront of promoting the integration of SDGs within higher education institutions, providing extensive resources and guidelines to support this endeavor. UNESCO’s work emphasizes the transformative potential of universities in fostering sustainable development. In “Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives” [

24], universities are encouraged to embed SDG-related content into their curricula, promote interdisciplinary research, and engage with local communities to address sustainability issues. The “Framework for the Implementation of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) beyond 2019” [

25] outlines strategic approaches for higher education institutions to contribute to the SDGs, including policy advocacy, capacity building, and the establishment of sustainable campus practices. As a result, a growing body of academic research has focused on how universities engage with the SDG framework and how their institutional and academic practices align with the SDGs. Examples of this engagement include incorporating sustainable development issues into the strategic planning of higher education institutions [

26], advancing SDG competencies in higher education [

22], integrating the SDGs into university academic programs [

27], exploring the power of research for achieving the SDGs [

28], aligning universities mission and activities with the SDG framework [

29], embedding SDGs into college curriculum and students learning activities [

30], incorporating SDG into the structures and missions of university-based centers [

31], and integrating SDGs in extra-curricular and co-curricular activities [

32]. Overall, the results of these studies demonstrate how university-generated knowledge can be used to deliver practical measures and actions needed to accelerate the SDGs implementation.

Some other important works in the field of universities and sustainable development goals include “Universities as the engine of transformational sustainability toward delivering the sustainable development goals: ‘Living labs’ for sustainability” by [

29], which provides a comprehensive overview of the role of universities in advancing sustainability; “Universities and Sustainable Development: The Role of University Research in Fostering Sustainable Development” by [

33], which explores the contributions of university research to sustainable development goals; and “The crosscutting impact of higher education on the Sustainable Development Goals” by [

12] and “Sustainability in Higher Education: From Doublethink and Newspeak to Critical Thinking and Meaningful Learning” by [

34], which delve into the pedagogical challenges and opportunities for integrating sustainability into higher education curricula. These articles represent foundational contributions to the literature, offering theoretical frameworks, empirical evidence, and practical insights into the role of universities in advancing sustainable development goals.

Despite the large number of studies on university engagement in the SDGs, there is not much empirical evidence to support this engagement in the Arab region, where almost all countries face immense sustainable development challenges [

35,

36,

37]. It is worth indicating that the majority of the existing literature focuses on linking only a portion of university operations to the SDGs. For instance, ref. [

35] assessed the extent of establishing an institutional framework for achieving sustainable development in Saudi Arabian universities. Therefore, this study sought to bridge this critical gap by exploring how the SDGs are being integrated into university practices. Unlike previous studies, this study addresses the integration of the SDGs in four functional areas of universities in the Arab region rather than just one functional area.

2. The Present Study

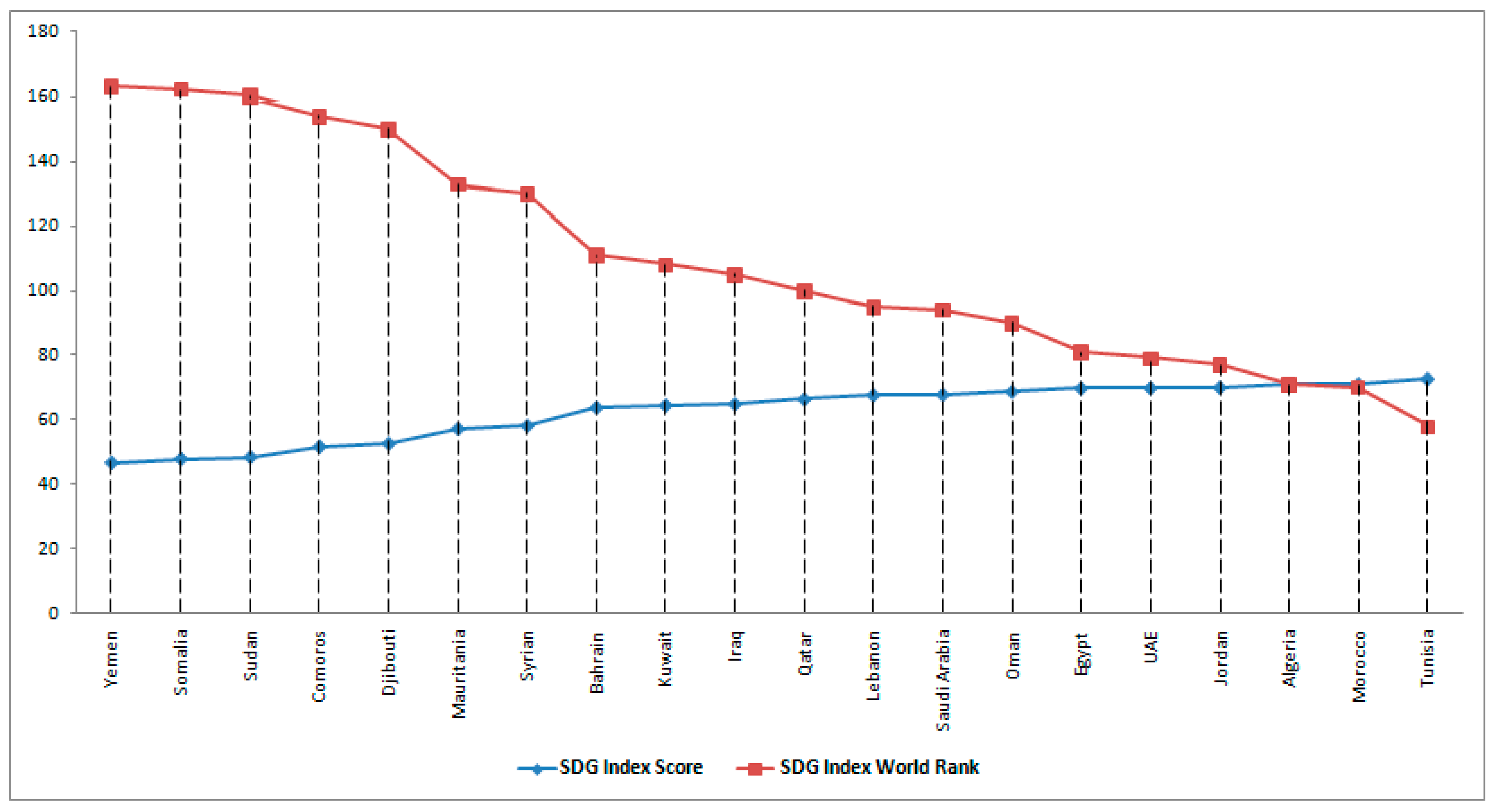

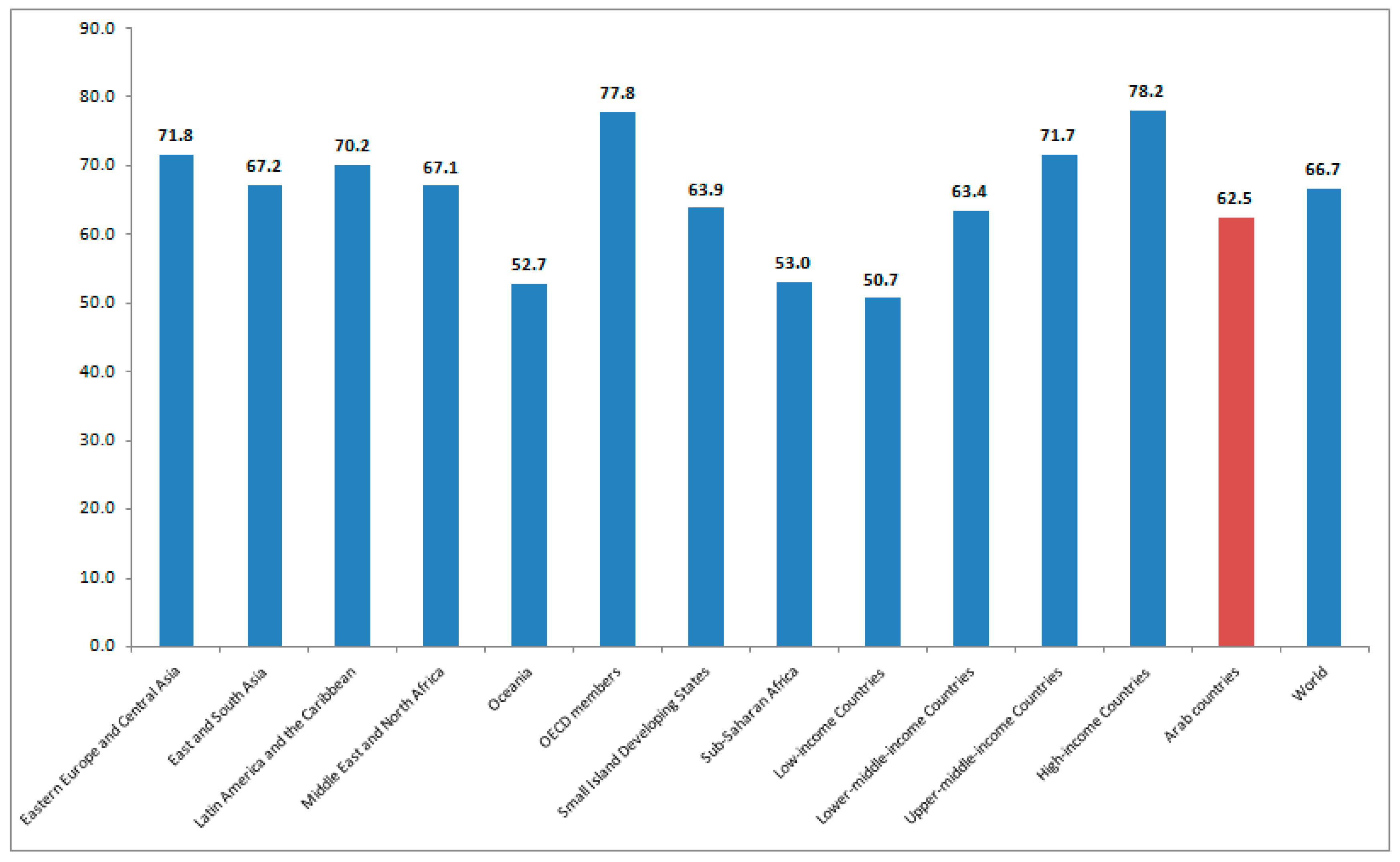

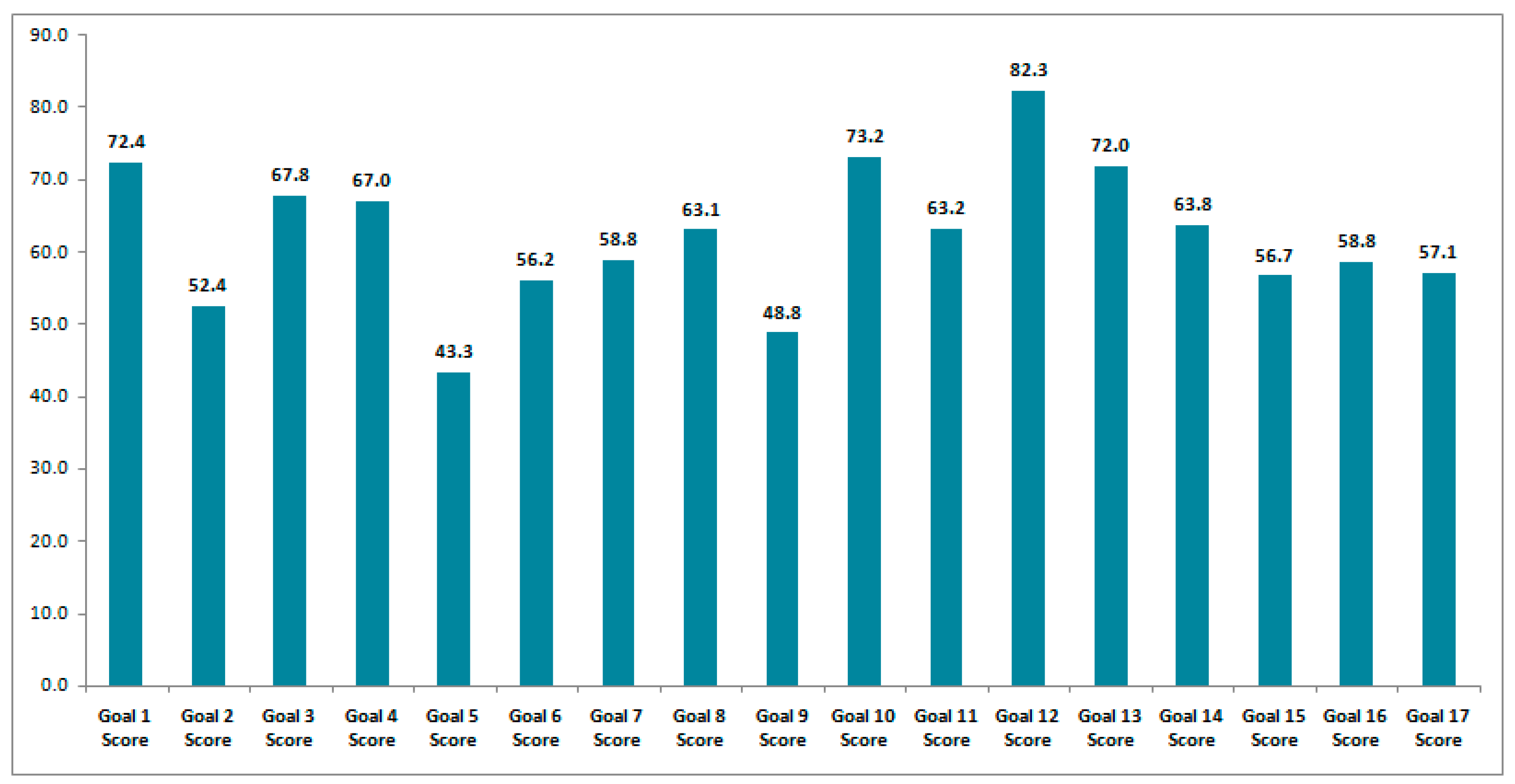

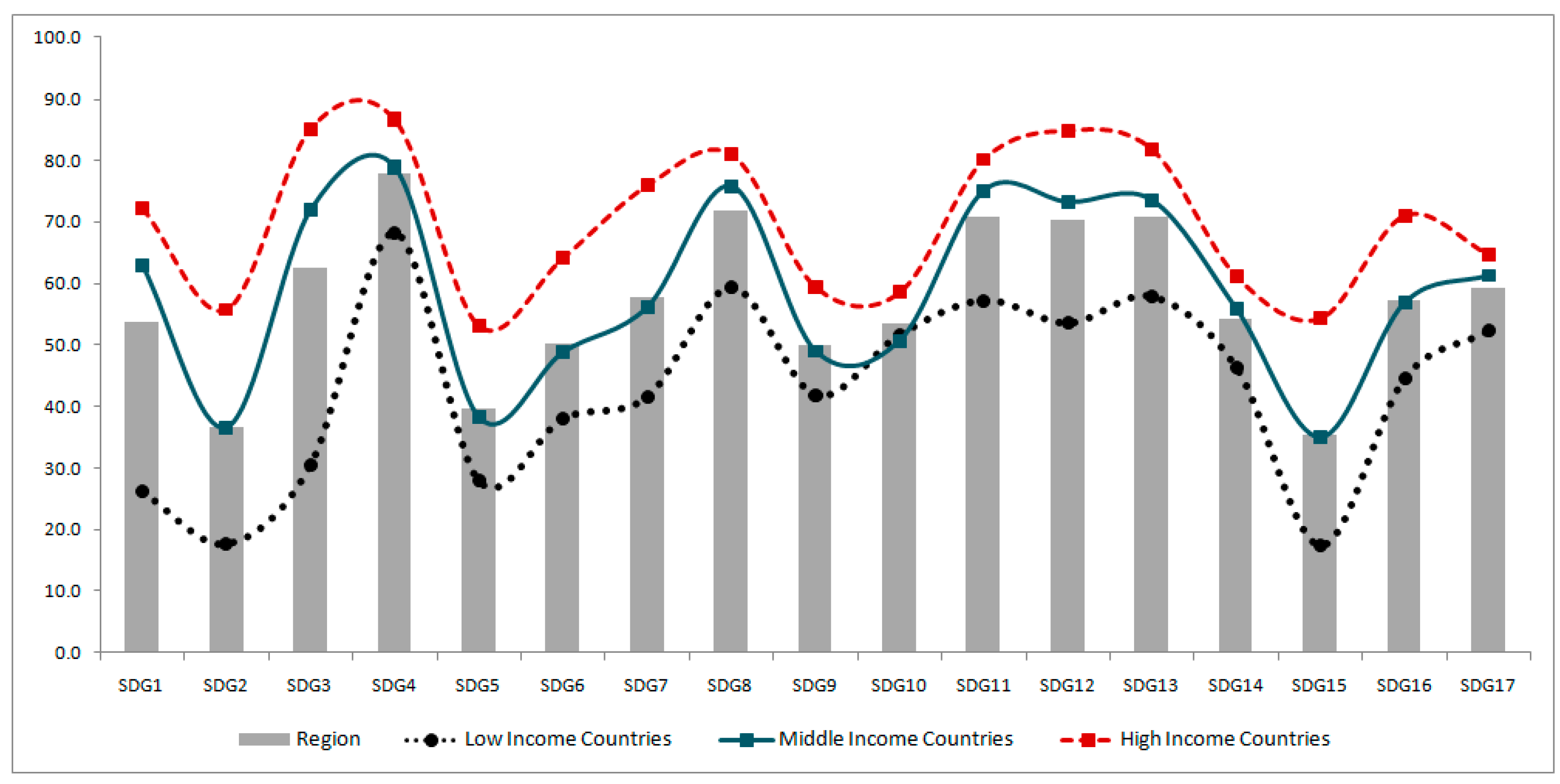

The Arab region as a whole has demonstrated very low performance on almost all SDGs; and most courtiers are not expected to meet most of these goals by the deadline due to several enormous economic, environmental, social, political, and technological challenges. Numerous regional and global reports have prominently revealed that many countries in the region are far off-track to achieve the SDG targets [

7,

36,

37]. For example, recent reports on the Global SDG Index show that many countries did not score high in terms of SDGs performance (see

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). The slow progress in implementing the SDGs was also emphasized in the 2022 Arab Region SDG Index and Dashboard Report [

36]. This report shows that a total of 19 Arab countries have not yet achieved a single SDG. It also reveals that SDG5 (Gender Equality), SDG2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) are the most significant challenges across the region.

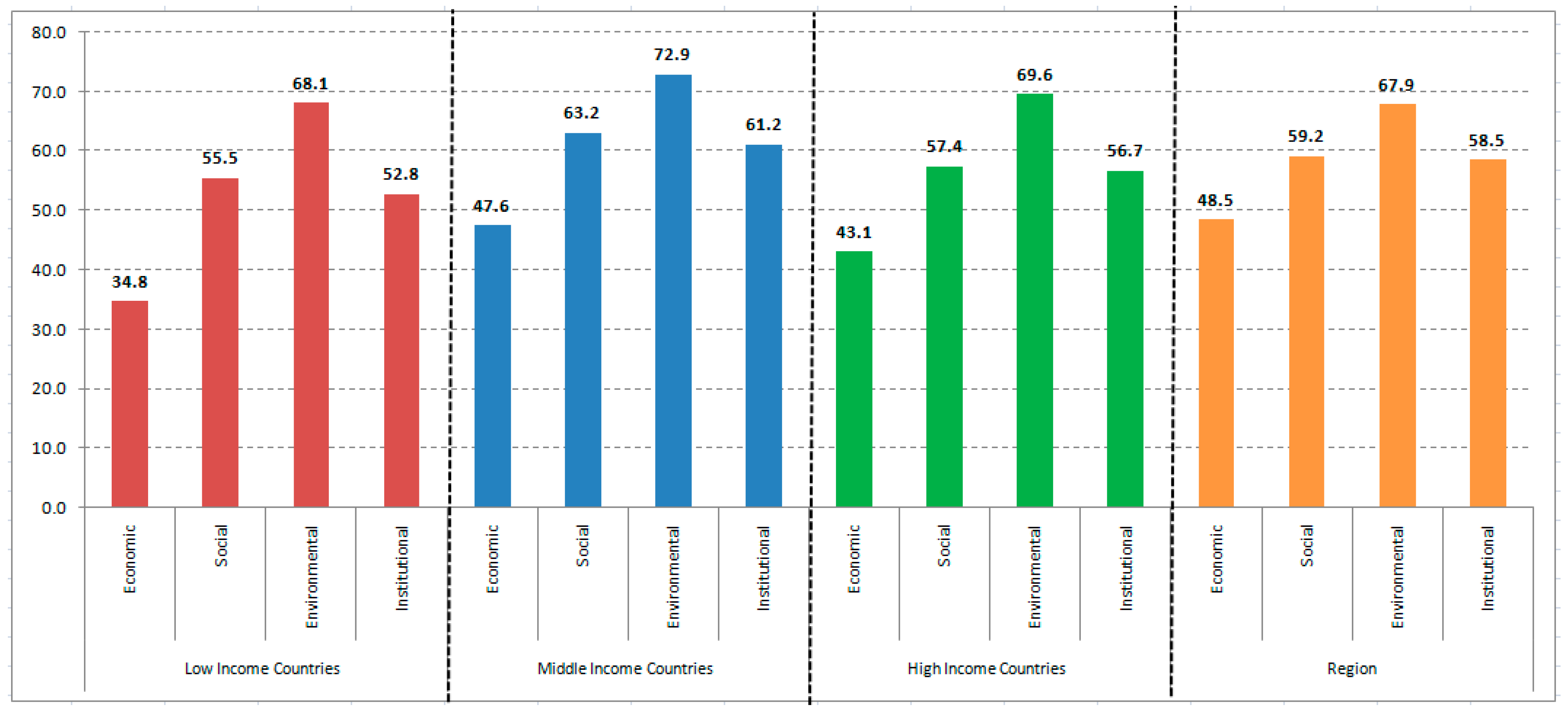

It is worth indicating that SDG performance varies widely at sub-regional levels, with very low performance being particularly prevalent in all low-income Arab countries (Comoros, Djibouti, Mauritania, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen). In contrast, the middle-income countries (Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Syrian, and Tunisia), and the high-income countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sultanate of Oman, and the United Arab Emirates) have shown some progress across some SDGs. For example, the 2022 Arab Region SDG Index and Dashboard Report demonstrated that five low-income countries along with two of the middle-income countries (Syria and Libya) each have 10 or more SDGs in the red category on the SDG Dashboard, indicating that they are far from achieving these goals.

The low performance and implementation rates of SDGs have created an urgent need to accelerate efforts and collaboration actions at the sub-national, national, and regional levels in all areas of the SDGs in order to make significant progress in the remaining years. One key action to accelerate the achievement of SDG targets in the region is to establish effective cross-sectoral and multi-stakeholder partnerships, as this will significantly accelerate the implementation, monitoring, evaluation, and reporting of the SDGs. There is no doubt that higher education institutions, particularly universities, are at the heart of all SDG implementation processes.

The importance of universities as key actors in advancing SDGs development goals is highlighted by emphasizing the need for integrated approaches that encompass institutional governance, community engagement, research, and education. Additionally, there is recognition of the unique contextual factors within the Arab region that influence university contributions to sustainable development, warranting tailored strategies and interventions. This context aims to explore how universities in the Arab region are effective in supporting and accelerating the achievement of the SDGs, thus contributing to enhancing the effectiveness of multi-sectoral partnerships at the national level in monitoring, evaluating, and reporting on progress towards the SDGs. To achieve this goal, four functional areas of the university must be considered, including institutional governance, partnership with the community, research productivity, and teaching and learning. Within this context, the present study attempted to assess how university practices in each functional area can contribute to the SDGs. Furthermore, an assessment of similarities and differences in university contributions to SDGs were also considered. Based on these considerations, the study was guided by the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: To what extent do universities in the Arab region prioritize the SDGs and integrate them into their institutional and program practices?

RQ2: What are the key drivers of Arab universities’ contribution to the sustainable development goals?

5. Discussion and Implications

The aim of this study was two-fold: to evaluate the prioritization of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) within the institutional framework of Arab universities and to explore the key factors that drive their involvement with these goals. In the first part, an SDG prioritization score was calculated to gain insights into the relative importance assigned by universities in the Arab region to each SDG. In the second part, ordinal logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate universities’ performance in four key functional areas: institutional capacity and governance, university–community partnerships and collaboration, research productivity, and teaching and learning. For analytical purposes, we considered the World Bank’s classification of Arab countries into three categories: low-income countries, middle-income countries, and high-income countries [

46].

5.1. Prioritization of the Sustainable Development Goals

The study on the prioritization of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by universities in the Arab region yielded insightful results concerning the focus areas of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at different regional levels. At the regional level, the results of the study identified SDG4 (Quality Education) and SDG8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) as the most prioritized goals at the regional level. This suggests that universities in our sample are placing significant emphasis on improving educational quality and fostering economic growth through decent employment opportunities. As for the least-prioritized SDGs, the results shows that the SDGs with the lowest priorities are SDG15 (Life on Land), SDG2 (No Hunger), and SDG5 (Gender Equality). This indicates a lesser focus on environmental sustainability, eradicating hunger, and promoting gender equality within these institutions. At the sub-regional level, the results revealed universities in high-income countries (HICs) prioritize SDGs more highly than those in middle-income countries (MICs) and low-income countries (LICs). This disparity may be due to differences in resources, infrastructure, and policy frameworks that support SDG initiatives.

These finding have important implications for policy and practice. Policymakers and universities in the region should consider providing targeted support for lower-priority SDGs and addressing disparities between universities. There is a need for targeted interventions and resource allocation to boost the prioritization of SDG15, SDG2, and SDG5. Universities need to incorporate the less-prioritized SDGs such as Life on Land (SDG15), No Hunger (SDG2), and Gender Equality (SDG5) into their core missions. This can be achieved through curriculum development, research initiatives, and community engagement programs that emphasize these critical areas. Universities and policymakers should develop strategies to address these gaps, potentially through partnerships, funding, and awareness campaigns. The lower prioritization of SDGs in MICs and LICs highlights the need for increased support and capacity building in these regions. Regional cooperation and funding can help bridge the gap and ensure a more balanced approach to achieving the SDGs across the Arab region. Inter-university collaboration and the sharing of best practices are crucial in this regard [

47]. Universities in high-income countries (HICs) can play a pivotal role in sharing best practices, knowledge, and resources with those in middle-income countries (MICs) and low-income countries (LICs). Establishing collaborative networks and partnerships can enhance the overall capacity of universities to prioritize and achieve the SDGs.

5.2. Factors Driving Arab Universities Contribution to Advancing Sustainable Development Goals

According to the ordinal logistic regression analysis, the study found that universities in the three sub-regions play a crucial role in supporting the Sustainable Development Goals through their institutional capacity and research productivity. Similar results are provided in several studies, e.g., [

18,

48,

49,

50]. The significance of the institutional governance factor in our study suggests that universities with strong institutional capacity and governance structures are more likely to integrate Sustainable Development Goals into their policies and operations. These universities tend to have comprehensive policies that integrate sustainability principles into the university’s strategic plans, operations, and mission and vision statements. A strong leadership commitment is crucial factor in this regard. Universities with top management actively supporting sustainability initiatives tend to have better integration of sustainable development goals into their governance structures [

35].

This involvement includes university presidents, deans, and department heads in sustainability efforts. This finding has an important implication for policy and practice. University leaders, especially those at universities with a low impact of institutional governance, should consider enhancing governance capacities. This includes providing resources for building robust governance frameworks that can support sustainability initiatives. Capacity-building programs addressing sustainable development issues should also be considered. Offering professional development opportunities and training workshops for university administrators and staff on sustainability issues can enhance their capacity [

51,

52,

53]. This, in turn, can promote a more integrated approach to strengthen universities’ role in accelerating the implementation of the SDGs. By addressing these institutional aspects, universities can enhance their governance structures and practices, leading to a more effective integration of Sustainable Development Goals and a greater contribution to national and regional sustainability efforts.

Similarly, the significance of the research productivity factor, as indicated by a large number of publications, ensures that new knowledge on sustainability issues is widely shared and accessible. This dissemination of knowledge is vital for informing policy and practice. Arab universities with higher publication rates in sustainability issues are more influential in policy-making processes related to sustainable development. This finding has several important implications for policymakers, university administrators, and other higher education stakeholders. For example, university leaders should recognize the importance of research productivity in universities as a key driver for sustainable development. This involves prioritizing research projects that align sustainability goals with universities’ institutional policies and strategic initiatives. Collaboration and partnerships also play a significant role in this context. Collaborative efforts between universities, industry, and government can enhance the impact of research on sustainable development [

54,

55]. Likewise, partnerships can facilitate the transfer of knowledge from academia to practical applications, thereby accelerating the achievement of the SDGs. Additionally, universities should consider establishing clear metrics for evaluating research productivity and its impact on sustainable development goals. This will help universities track their sustainability-related research outputs, demonstrate their contributions to the SDGs, and identify areas for improvement.

It is worth noting that the research productivity impact of universities from high-income countries, such as those in the GCC region, is significantly higher than that of universities from low- and middle-income countries. According to the perspectives of the faculty members in our sample, universities in these countries provide sufficient funding and resources to support high research productivity. They also make substantial investments in research infrastructure, grants, and scholarships for sustainability-focused research projects. This has resulted in an increase in research output from GCC universities and has enhanced their ability to contribute to the SDGs.

The partnership between Arab universities and the community was identified as a significant factor in the contribution of universities from high- and middle-income countries towards the SDGs. This finding aligns with existing research that has highlighted the significant role of university–community partnerships in accelerating the achievement of the SDGs [

56,

57,

58]. Consistent with these studies, our study revealed that Arab universities actively engaging in partnerships and collaborative projects with local communities, governments, NGOs, and industry partners tend to demonstrate higher success rates in advancing the implementation of the SDGs. These collaborations and partnerships enable resource sharing, knowledge exchange, and the co-creation of solutions, which are crucial for effectively addressing local sustainable development challenges.

This finding has important practical implications for policy and practice. Policymakers at the national level and university leaders should encourage and support initiatives that promote stronger connections between universities and their surrounding communities. Universities in low-income countries, in particular, should actively seek out and cultivate partnerships with various stakeholders, including local governments, NGOs, and industry partners, to enhance their contributions to the SDGs. This could involve providing funding and incentives for collaborative projects, prioritizing those that demonstrate clear potential in addressing the challenges related to the implementation of the SDGs. By strengthening these partnership aspects, promoting resource sharing, and fostering co-creation of solutions, Arab universities can significantly contribute to the implementation of sustainable development in their communities and beyond.

The results of the regression analysis revealed a significant impact of teaching and learning practices at universities in high-income countries on accelerating the achievement of the SDGs. This finding aligns with previous studies that have emphasized the significance of academic programs in higher education institutions for advancing the implementation of the SDGs [

27,

59]. The significance of this factor in our study emphasizes that universities are successful in aligning their curricula with the needs of sustainable development. This alignment may reflect that academic programs are adopting interdisciplinary approaches that integrate various fields of study to provide a comprehensive understanding of sustainability issues. This integration helps students acquire a unique set of skills and specialized knowledge that enables them to think critically about global challenges and understand the interconnectedness of social, economic, and environmental dimensions of sustainability.

This finding has practical implications for policy and curriculum development. Higher education institutions should continue to emphasize and invest in curriculum development that aligns with the SDGs [

60]. This includes fostering interdisciplinary programs and encouraging innovative teaching practices that integrate sustainability concepts across various disciplines [

61]. Universities should prioritize regional collaboration to enhance educational efforts aimed at achieving the SDGs. Universities in high-income countries should share their best teaching and learning practices and collaborate with those in low- and middle-income countries. This collaboration could involve exchange programs, joint research initiatives, and collaborative curriculum development projects. Additionally, universities should adopt continuous improvement mechanisms to assess and improve their teaching and learning practices in order to stay aligned with the evolving nature of the SDGs. This includes conducting regular curriculum reviews, incorporating feedback from students and industry partners, and staying updated with the latest sustainability research and trends.

However, despite the significant benefits of integrating SDGs into teaching and learning practices, several challenges need to be addressed in order to fully realize these benefits. Some challenges include resource constraints, insufficient training of faculty in sustainability issues, and a lack of strong institutional commitment to sustainability. In this regard, it is worth noting that many universities in the region, especially those in low-income countries, face resource constraints that limit their ability to implement comprehensive sustainability education programs. This limitation can hinder the effectiveness of such programs, preventing students from gaining the full breadth of knowledge and skills necessary to effectively address sustainability issues. To overcome these challenges, strong institutional support is required. This includes not only financial support but also administrative backing and a commitment to sustainability from the highest levels of the institution.

Our study provides a comprehensive analysis of the role of Arab universities in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While our findings are robust, it is important to contextualize these results by comparing them with similar studies conducted in other regions. For example, many studies conducted in Europe have demonstrated that universities play a crucial role in promoting sustainability through research, education, and community engagement. For instance, ref. [

62] found that European universities are increasingly integrating SDGs into their curricula and operational strategies, emphasizing the importance of multi-disciplinary approaches and partnerships with local communities. In comparison, our study indicates that Arab universities are also making significant strides in these areas but face unique challenges such as limited funding and political instability. Similarly, Asian universities have shown a strong commitment to SDGs through large-scale research projects and international collaborations. For example, ref. [

63] found that Indian universities are leveraging community engagement and public–private partnerships to advance sustainability initiatives. In contrast, our research indicates that Arab universities are beginning to adopt similar technological innovations but at a different pace and scale due to varying resource availability and socio-economic contexts. In Africa, universities are increasingly recognized as key players in promoting sustainable development. For instance, a study by [

64] found that universities are actively involved in community-based sustainability projects despite facing challenges such as limited funding and political instability. Our findings resonate with these efforts but also reveal that Arab universities are focusing more on specific regional priorities such as water scarcity and food security.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study explores the fundamental role of Arab universities in driving forward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) within the region. Through a multi-dimensional analysis focusing on institutional capacity, university–community partnerships, research productivity, and teaching and learning, the research underscores the potential contributions of universities towards achieving the SDGs. By examining these functional domains, the study not only sheds light on the diverse ways in which universities can support sustainable development but also emphasizes the importance of fostering effective multi-sectoral partnerships at the national level. Through collaborative efforts encompassing monitoring, evaluation, and reporting progress, universities can enhance their effectiveness in advancing the SDGs, thus contributing significantly to the broader sustainable development agenda in the Arab region. Furthermore, the research highlights the need for a careful and meticulous understanding of the similarities and disparities among universities in their contributions to the SDGs. By recognizing variations in institutional capacities, collaboration frameworks, and research priorities, policymakers and stakeholders can tailor strategies and interventions to leverage the strengths of each university towards sustainable development. Ultimately, the findings of this study serve as a call to action for universities, policymakers, and civil society actors to prioritize sustainable development within higher education agendas, foster cross-sectoral partnerships, and empower universities to fulfill their potential as engines of social change and progress in the Arab region. Based on the findings of the study, it is clear that Arab universities have the potential to significantly advance the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through their institutional capacities, partnerships, research endeavors, and educational practices. However, disparities among universities in their contributions to the SDGs underscore the importance of considering this result. Recommendations include fostering a culture of sustainability across university campuses, enhancing interdisciplinary collaboration within academia and with external stakeholders, and providing resources and incentives to support research and teaching focused on sustainable development. Additionally, promoting inclusivity and gender equality within university structures and initiatives can enhance the impact of universities in addressing the SDGs. Furthermore, strengthening monitoring and evaluation mechanisms and promoting knowledge sharing among universities can facilitate the exchange of best practices and accelerate progress towards the SDGs in the Arab region. Overall, concerted efforts are needed to harness the full potential of Arab universities in driving sustainable development and ensuring a prosperous future for the region.

Finally, we acknowledge that the governance structure at universities plays a crucial role in shaping policies, strategies, and the overall environment for advancing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The diversity in governance structures across universities can influence the effectiveness and implementation of SDG initiatives, thereby impacting the outcomes. This study considers that governance structure is crucial and needs future in-depth investigation in future research. Future research could focus on a comparative analysis of governance models in different universities and their effectiveness in promoting SDGs.