Carbon Footprint for Jeans’ Circular Economy Model Using Bagasse

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Purpose

1.2.1. Raw Material Production Process: Use of Bagasse as Raw Material

1.2.2. Dyeing Process: Environmentally Friendly Rope Dyeing (Improved Dyeing)

1.2.3. Disposal Process: Carbon Sequestration of Used Jeans and Waste Generated in the Production Process

2. Research Methods

2.1. Evaluation Target and System Boundary

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Sugarcane Cultivation

2.2.2. Bagasse and Bagasse Powder Production

2.2.3. Bagasse Washi Yarn Production

- (1)

- Cultivation and Pulping of Manila Hemp

- (2)

- Paper Production

- (3)

- Slitting and Twisting

2.2.4. Cotton Yarn Production

2.2.5. Dyeing of Cotton Yarn

2.2.6. Weaving

2.2.7. Fabric Finishing

2.2.8. Cutting and Sewing

2.2.9. Transportation

2.2.10. Sales

2.2.11. Laundry

2.2.12. Biochar Processing

3. Results

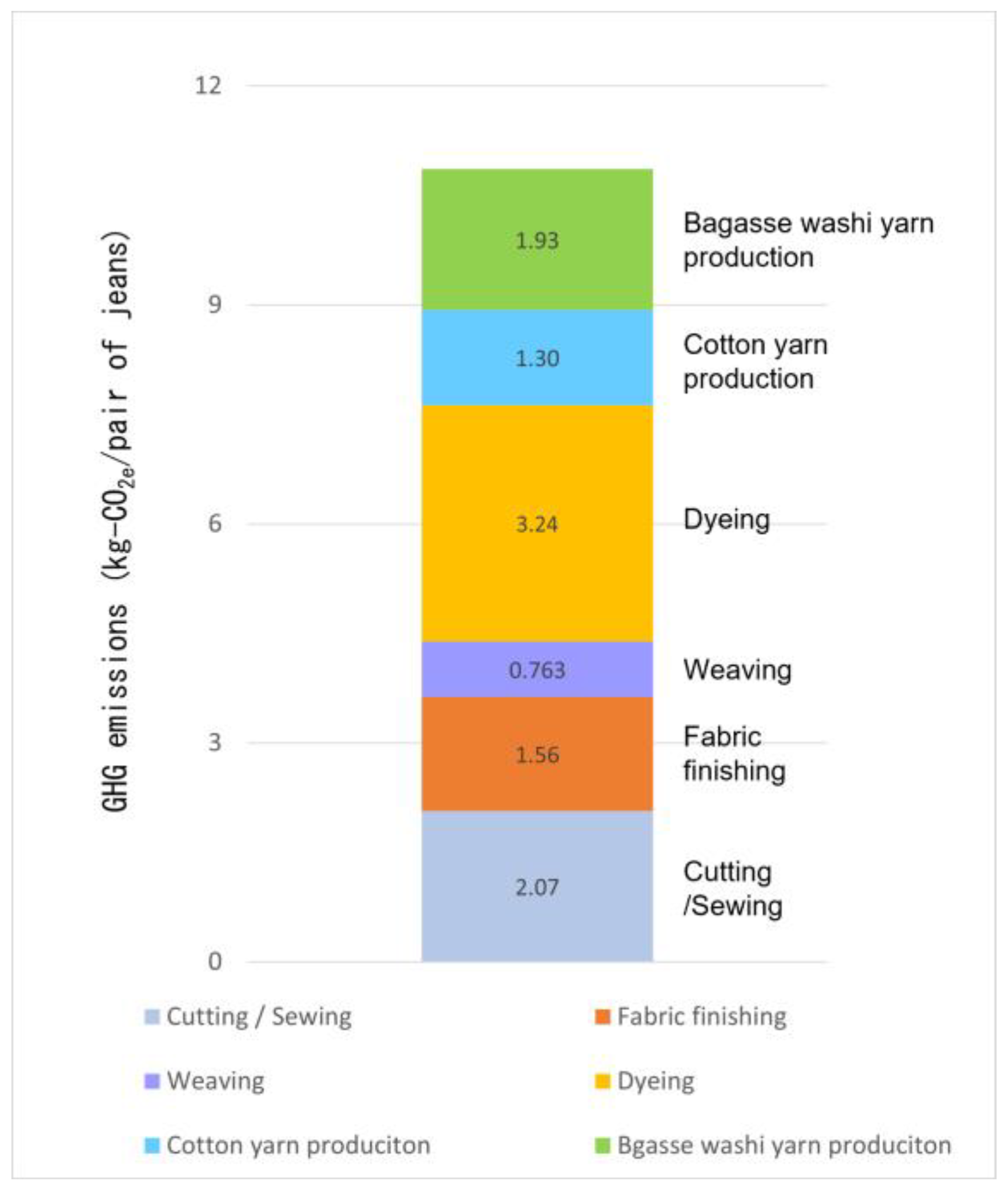

3.1. Calculation of GHG Emissions up to Bagasse Washi Jeans Production

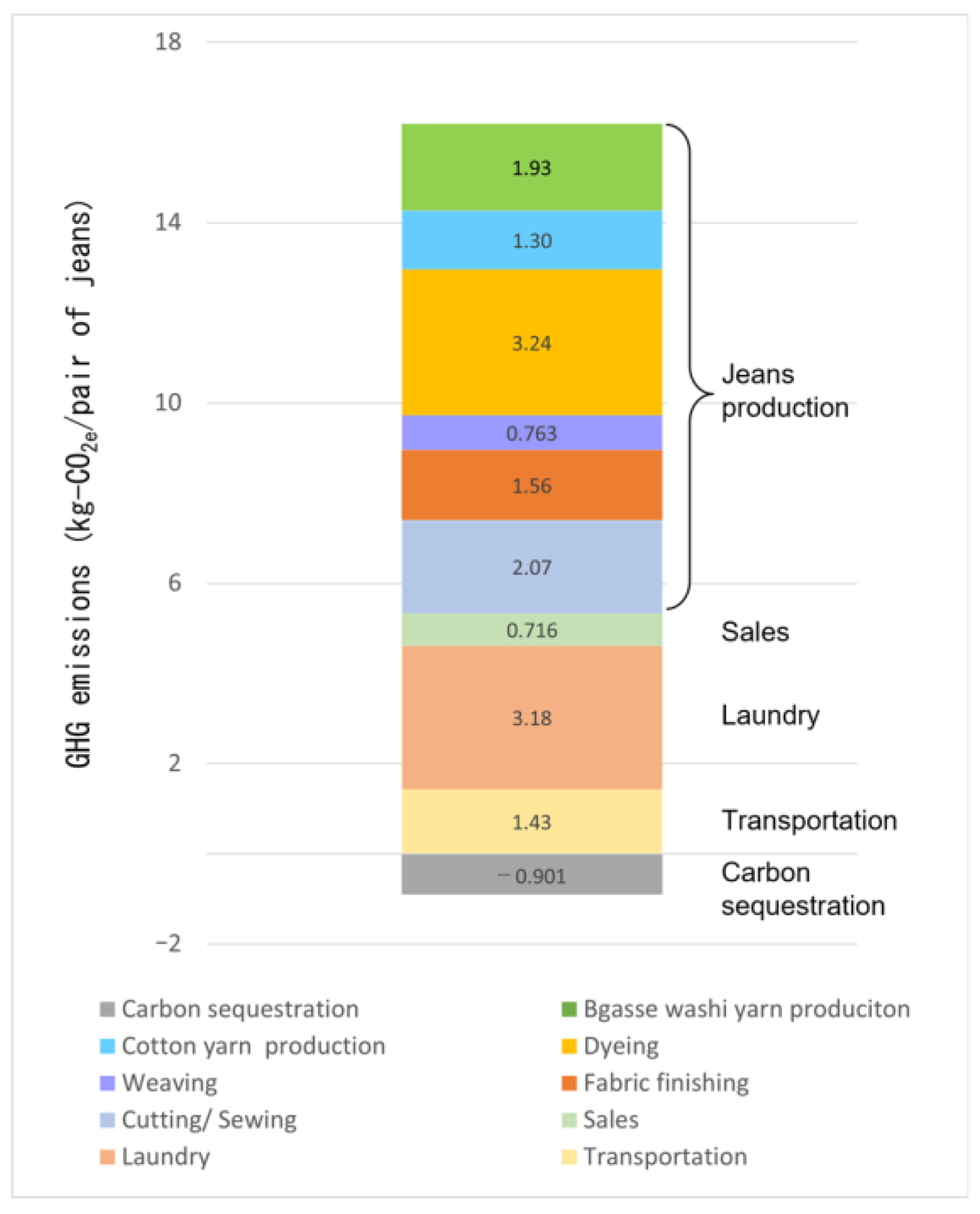

3.2. Calculation of GHG Emissions over the Entire Life Cycle

4. Discussion

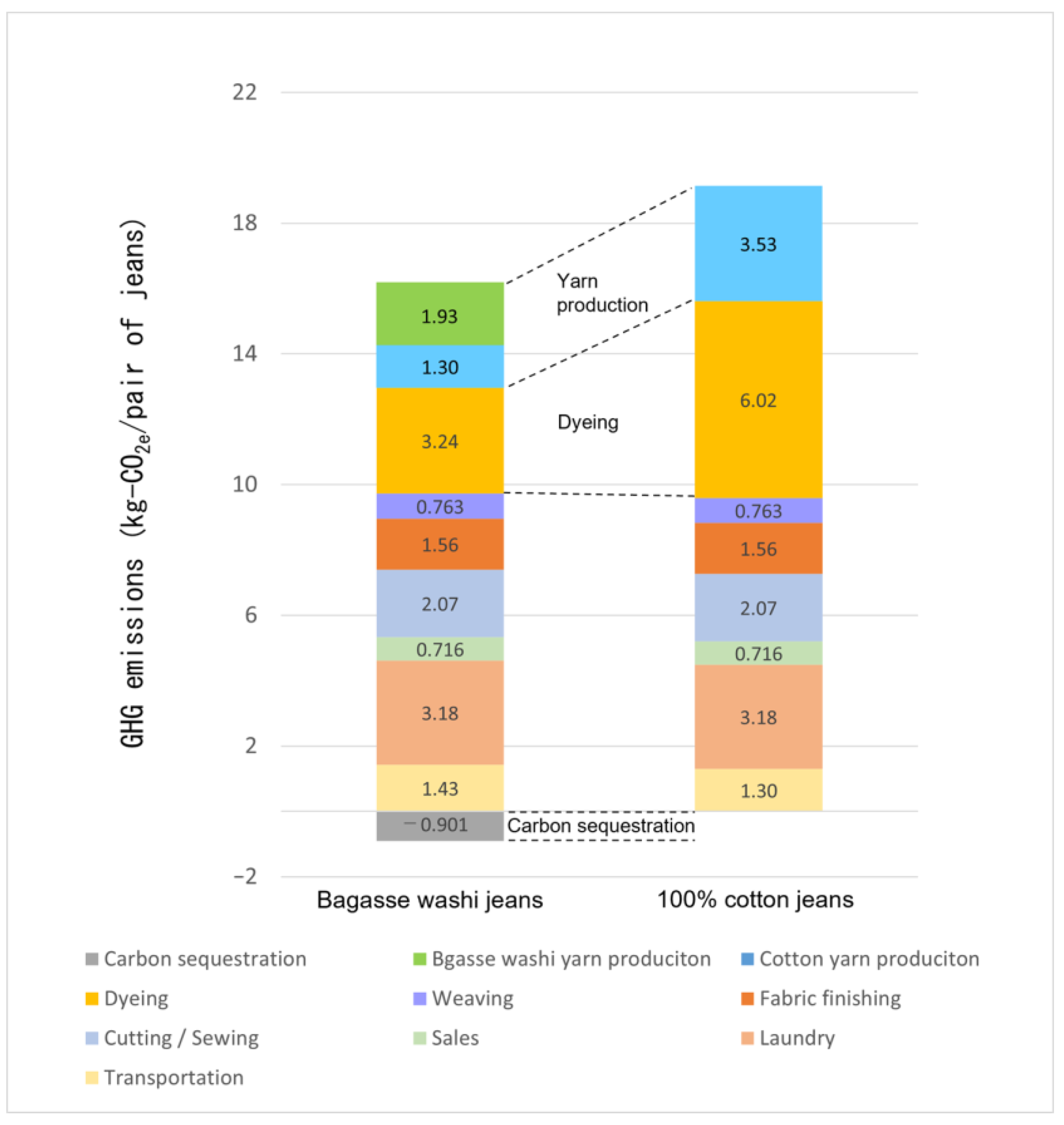

4.1. Comparison of Bagasse Washi Jeans and Conventional Jeans (100% Cotton)

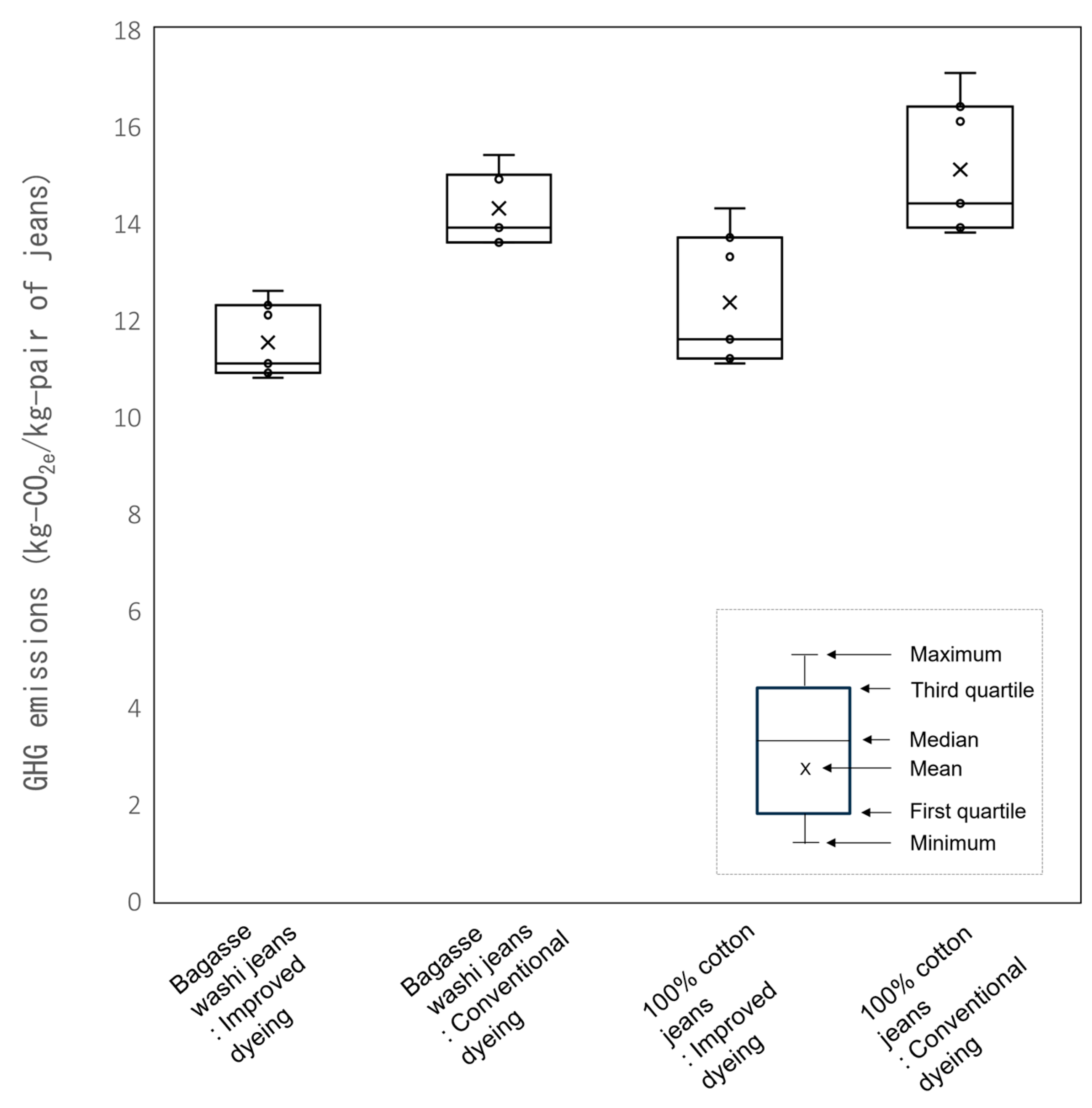

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

4.3. Potential to Reduce GHG Emissions

5. Limitations of This Study

6. Conclusions and Future Research Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The Japan Textiles Importers Association. Japan’s Apparel Market and Imports; The Japan Textiles Importers Association: Osaka City, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, F.; Tian, M.; Qu, L.; Perry, P.; Owens, H.; Liu, X. Textile Waste Fiber Regeneration via a Green Chemistry Approach: A Molecular Strategy for Sustainable Fashion. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2105174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of the Environment. FY 2020 Survey on Fashion and the Environment—Results of the “Fashion and the Environment” Survey; Ministry of the Environment: Tokyo, Japan, 2020.

- Global Fashion Agenda. Fashion on Climate; Global Fashion Agenda: København, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- H&M Group. Available online: https://hmgroup.com/sustainability/circularity-and-climate/circularity/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Patagonia Inc. Available online: https://www.patagonia.jp/stories/our-quest-for-circularity/story-96496.html (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Curelabo Co. Ltd. Available online: https://curelabo.co.jp/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment-Principles and Framework. 2nd ed, International Standard Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment-Requirements and Guidelines. 1st ed, International Standard Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Baydar, G.; Ciliz, N.; Mammadov, A. Life cycle assessment of cotton textile products in Turkey. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 104, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Xiao, R.; Yuan, Z. Life cycle assessment of cotton T-shirts in China. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi Strauss & Co. The Life Cycle of a Jean. 2015. Available online: https://levistrauss.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Full-LCA-Results-Deck-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Mistra Future Fashion. Environmental Assessment of Swedish Clothing Consumption—Six Garments, Sustainable Futures. 2019. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/270109142.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Hedman, A.E. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Jeans: A Case Study Performed at Nudie Jeans; Bachelor, KTH Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ecoinvent. Available online: https://ecoinvent.org/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Cotton Incorporated. Monthly Economic Letter-Cotton Market Fundamentals & Price Outlook JULY 2022; Cotton Incorporated: Cary, NC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, C.; Ren, F.; Liu, Z. Could the recycled yarns substitute for the virgin cotton yarns: A comparative LCA. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 2050–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velden, N.M.; Patel, M.K.; Vogtländer, J.G. LCA benchmarking study on textiles made of cotton, polyester, nylon, acryl, or elastane. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, J.; Thevs, N.; Gusovius, H.; Sigmund, I.; Brückner, T.; Beckmann, V.; Abdusalik, N. Carbon and phosphorus footprint of the cotton production in Xinjiang, China, in comparison to an alternative fibre (Apocynum) from Central Asia. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinkstep. Life Cycle Assessment of Cotton Cultivation Systems—Better Cotton, Conventional Cotton and Organic Cotton. 2019. Available online: https://www.laudesfoundation.org/media/43anrffi/4332-environmentall-care-port-june19.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Nalley, L.; Popp, M.; Niederman, Z.; Brye, K.; Matlock, M. How Potential Carbon Policies Could Affect Where and How Cotton Is Produced in the United States. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2012, 41, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabbaz, B.G. Life Cycle Energy Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Australian Cotton: Impact of Farming Systems. Master’s Thesis, University of Southern Queensland, Queensland, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, F.; Dargusch, P.; Smith, C.; Grace, P.R. Application of the Crop Carbon Progress Calculator in a ‘farm to ship’ cotton production case study in Australia. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 103, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, A.M.; Moore CC, S.; Nogueira, A.R.; Kulay, L.; Ravagnani, M.A. Assessment of potential alternatives for improving environmental trouser jeans manufacturing performance in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avadí, A.; Marcin, M.; Biard, Y.; Renou, A.; Gourlot, J.; Basset-Mens, C. Life cycle assessment of organic and conventional non-Bt cotton products from Mali. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 678–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aid by Trade Foundation. Life Cycle Assessment of Cotton Made in Africa. 2021. Available online: https://cottonmadeinafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/CmiA_LCA-Study_2021.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Cotton Incorporated. Life Cycle Assessment of Cotton Fiber & Fabric Full Report. 2012. Available online: https://cottoncultivated.cottoninc.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/2012-LCA-Full-Report.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Cotton Incorporated. Lca Update of Cotton Fiber and Fabric Life Cycle Inventory. 2017. Available online: https://resource.cottoninc.com/LCA/2016-LCA-Full-Report-Update.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Textile Exchange. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Organic Cotton-A Global Average; Textile Exchange: Lamesa, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Munasinghe, P.; Druckman, A.; Dissanayake, D.G.K. A systematic review of the life cycle inventory of clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 20, 128852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, C.; Xie, R.; Yu, H.; Sun, M.; Li, F. Environmental assessment of fabric wet processing from gate-to-gate perspective: Comparative study of weaving and materials. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazan, H.; Akgul, D.; Kerc, A. Life cycle assessment of cotton woven shirts and alternative manufacturing techniques. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy. 2020, 22, 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemdeeb, R.; Saint, R.; Pomponi, F.; Pratt, K.; Lenaghan, M. Beyond recycling: An LCA-based decision-support tool to accelerate Scotland’s transition to a circular economy. Resourc. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 13, 200069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrant, L.; Olsen, S.I.; Wangel, A. Environmental benefits from reusing clothes. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, B.; Svanström, M.; Peters, G.; Rydberg, T. A Carbon Footprint of Textile Recycling: A Case Study in Sweden. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, T.; Sakai, Y.; Ishikawa, M.; Inaba, A. Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions by Reusing and Recycling Used Clothing in Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, L.; Duraivadivel, P.; Hariprasad, P.; Naik, S.N. Utilization and re-use of solid and liquid waste generated from the natural indigo dye production process—A zero waste approach. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 301, 122721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saling, P.; Kicherer, A.; Dittrich-Krämer, B.; Wittlinger, R.; Zombik, W.; Schmidt, I.; Schrott, W.; Schmidt, S. Eco-efficiency41 analysis by basf: The method. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2002, 7, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidan, F.S.; Aydoğan, E.K.; Uzal, N. Multi-dimensional Sustainability Evaluation of Indigo Rope Dyeing with a life cycle approach and hesitant fuzzy analytic hierarchy process. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 309, 127454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, A.P.; Duraisamy, G. Carbon Footprint on Denim Manufacturing. In Handbook of Ecomaterials; Martínez, L.M.T., Kharissova, O.V., Kharisov, B.I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1581–1598. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, J.; Nielsen, K.S.; Birkved, M.; Joanes, T.; Gwozdz, W. The environmental impacts of clothing: Evidence from United States and three European countries. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 2153–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, X.; Ding, X. Carbon and water footprints assessment of cotton jeans using the method based on modularity: A full life cycle perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 332, 130042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidan, F.S.; Aydoğan, E.K.; Uzal, N. The impact of organic cotton use and consumer habits in the sustainability of jean production using the LCA approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. 2023, 30, 8853–8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inventory Database (IDEA) for Environmental Analysis developed by the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) and Japan Environmental Management Association for Industry (JEMAI). Available online: https://idea-lca.com/en/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Okinawa Prefecture. Sugarcane and Ama-Sugar Production Results for the Year 2020/2021; Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Okinawa Prefecture: Tokyo, Japan, 2021.

- Kikuchi, K.; Hondo, H. Environmental Impacts and Employment Effects Induced by Utilization of Biomass Resources in Local Areas: A Case Study of a Bioethanol Project in Miyako-Island. J. Jpn. Inst. Energy 2011, 90, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan. The Greenhouse Gas Inventory Office of Japan (GIO); National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan: Tsukuba, Japan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Agriculture & Livestock Industries Corporation (ALIC). Statistical Data Business-Related Data 1; Agriculture & Livestock Industries Corporation (ALIC): Tokyo, Japan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, T.; Suzuki, K.; Sato, M. Technology for Fuel Ethanol Production from Molasses Bagasse in Sugar Mills. TSK Technical. J. 2010, 14, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Cortez, C.; Alcantara, A.; Pacardo, E.; Rebancos, C. Life Cycle Assessment of Manila Hemp in Catanduanes, Philippines. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2015, 18, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbaña, E.; Ordonez, P.; Ordóñez, Y.F.; Guerrero, V.A.; Mera, M.C.; Carvajal, E. 6—Abaca: Cultivation, obtaining fibre and potential uses. In Handbook of Natural Fibres, 2nd ed.; Kozłowski, R.M., Mackiewicz-Talarczyk, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. LCA Study Report on Textile Products (Clothing)-Updated Version Due to Correction of Data on Dyeing Process, etc.; Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry: Tokyo, Japan, 2009.

- NX-GREEN Calculator. Available online: https://www.nittsu.co.jp/logistics_solution/it/eco_solution/emission-cal.html (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.co.jp/maps/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Seii, E.; Itagaki, M.; Nagayama, M. Evaluation of domestic washing in Japan using life cycle assessment (LCA). Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Guideline for the Maximum Amount of Biochar to Be Applied. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/seisan/kankyo/ondanka/biochar01.html (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Lehmann, J.; Gaunt, J.; Rondon, M. Bio-char sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems—A review. Mitig. Adapt. Strategy Glob. Chang. 2006, 11, 403–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J. A handful of carbon. Nature 2007, 447, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kua, H.W.; Koh, H.J. Application of biochar from food and wood waste as green admixture for cement mortar. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619–620, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Cowie, A.L.; Mai TL, A.; Brandao, M.; Rosa RA, R.; Kristiansen, P.; Joseph, S. Climate-change and health effects of using rice husk for biochar-compost: Comparing three pyrolysis systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tang, Y.; Ren, N.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y. Effect of mineral constituents on temperature-dependent structural characterization of carbon fractions in sewage sludge-derived biochar. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3342–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; da Silva, J.P., Jr.; Rondon, M.; Cravo, M.D.S.; Greenwood, J.; Nehls, T.; Steiner, C.; Glaser, B. Slash-and-char-a feasible alternative for soil fertility management in the central Amazon. In Proceedings of the 17th World Congress of Soil Science, Bangkok, Thailand, 14–21 August 2002; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan. National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Report of Japan 2020. 2020. Available online: https://cger.nies.go.jp/publications/report/i150/i150.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Zamani, B.; Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M. Life cycle assessment of clothing libraries: Can collaborative consumption reduce the environmental impact of fast fashion? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levänen, J.; Uusitalo, V.; Härri, A.; Kareinen, E.; Linnanen, L. Innovative recycling or extended use? Comparing the global warming potential of different ownership and end-of-life scenarios for textiles. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 054069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Paper Association, LCA Subcommittee. CO2 Emissions in Life Cycle Assessment of Paper and Paperboard; Japan Paper Association, LCA Subcommittee: Tokyo, Japan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.; Wang, Y.; Shi, L.; Klemeš, J.J. Uncovering energy use, carbon emissions and environmental burdens of pulp and paper industry: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2018, 92, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Non-Wood Fibres for Pulp and Paper. Original 1983, Translated 1984; Translated by Suzuki, T. J. Jpn. Tech. Assoc. Pulp Pap. Ind. 1984, 38, 174–195. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Amount of Activity per kg of Sugarcane | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Sugarcane seedlings | - | |

| Agrochemical | 1.38 × 10−3 | kg | |

| Fertilizer | 5.90 × 10−2 | kg | |

| Diesel oil | 2.22 × 10−6 | kL | |

| Rainwater | - | ||

| Output | Sugarcane | 1.00 | kg |

| Waste | 1.44 × 10−2 | kg | |

| Item | Amount of Activity per kg of Bagasse Washi | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Bagasse powder | 2.83 × 10−1 | kg |

| Manila hemp pulp | 1.12 | kg | |

| Polyethylene oxide (adhesive) | 5.59 × 10−3 | kg | |

| Polyamine epichlorohydrin resin solution (5% solution) (wet paper strength agent) | 3.80 × 10−3 | kg | |

| Carboxyquimethylcellulose (yield improver) | 2.51 × 10−3 | kg | |

| Polyacrylamide resin solution (20% solution) (paper strength enhancer) | 3.14 × 10−2 | kg | |

| Distilled water | 9.74 × 10−2 | kg | |

| Public Electricity | 2.32 | kWh | |

| LPG | 3.43 × 10−1 | kg | |

| Groundwater | 5.79 × 102 | kg | |

| Out | Bagasse washi | 1.00 | kg |

| Waste | 3.98 × 10−1 | kg | |

| Wastewater | 5.82 × 102 | kg | |

| Item | Amount of Activity per kg of Dyed Cotton Yarn | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Cotton yarn | 1.00 | kg |

| Indigo dye | 9.52 × 10−2 | kg | |

| Hydrosulfite (Na2S2O4) | 9.52 × 10−2 | kg | |

| Sodium hydroxide | 7.14 × 10−2 | kg | |

| Surfactant (for detergent) | 7.69 × 10−1 | kg | |

| Starch | 9.52 × 10−2 | kg | |

| Sodium chloride (for electrolytic water) | 7.94 × 10−3 | kg | |

| Public power | 1.08 | kWh | |

| Heavy oil A (for boilers) | 1.59 | L | |

| Underground water | 1.78 × 10−1 | m3 | |

| Output | Dyed cotton yarn | 1.00 | kg |

| Waste | 3.01 × 10−3 | kg | |

| Wastewater | 1.78 × 10−1 | m3 | |

| Item | Amount of Activity per kg of Bagasse Washi Denim Fabric | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Bagasse washi denim fabric | 1.00 | kg |

| LPG | 1.07 | MJ | |

| Heavy oil A (for boilers) | 1.54 × 101 | MJ | |

| Public electricity | 4.28 × 10−1 | kWh | |

| Water supply | 3.67 × 10−3 | m3 | |

| Industrial water | 2.51 × 10−2 | m3 | |

| Softeners | 5.43 × 10−3 | kg | |

| Penetrants | 5.55 × 10−3 | kg | |

| Output | Bagasse washi denim fabric | 1.00 | kg |

| Wastewater | 2.88 × 10−2 | m3 | |

| Reports | This Study | Levi’s [13] 0.34 kg | Mistra Future Fashion [14] 0.477 kg | Morita et al. [25] 0.959 kg | Periyasamyet al. [41] 0.57 kg | Sohn et al. [42] 1 kg | Luo et al. [43] 1 kg | Fidan et al. [44] 0.67 kg | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bagasse Washi Jeans (Improved Dyeing) 0.750 kg | 100% Cotton Jeans (Conventional Dyeing) 0.750 kg | ||||||||||||||||||||

| GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e) | Ratio (%) | GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e) | Ratio (%) | GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e) | Ratio (%) | GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e) | Ratio (%) | GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e) | Ratio (%) | GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e) | Ratio (%) | GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e) | Ratio (%) | GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e) | Ratio (%) | GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e) | Ratio (%) | ||||

| Fabric production | Yarn production | Bagasse washi yarn | 1.93 | 29.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Cotton yarn | 1.31 | 3.53 | 25.3 | 1.19 × 101 | 82.1 | 3.01 | 34.6 | 1.99 | 26.1 | 1.90 × 101 | 75.3 | 2.81 × 101 | 100 | 4.71 | 5.2 | 4.28 | 77.4 | ||||

| Dyeing | 3.24 | 29.8 | 6.02 | 43.2 | 2.83 | 32.5 | 4.66 × 101 | 51.7 | |||||||||||||

| Weaving /Fabric finishing | 2.32 | 21.4 | 2.32 | 16.6 | 1.41 | 16.3 | 1.62 | 21.2 | |||||||||||||

| Jeans production | Cutting/Sewing /Finishing | 2.07 | 19.1 | 2.07 | 14.9 | 2.60 | 17.9 | 1.45 | 16.7 | 4.02 | 52.7 | 6.26 | 24.7 | 3.89 × 101 | 43.1 | 1.25 | 22.6 | ||||

| Total | 1.09 × 101 | 100 | 1.39 × 101 | 100 | 1.45 × 101 | 100 | 8.70 | 100 | 7.63 | 100 | 2.53 × 101 | 100 | 2.81 × 101 | 100 | 9.02 × 101 | 100 | 5.53 | 100 | |||

| Process | Bagasse Washi Jeans in this Study | Fidan et al. [44] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e/Pair of Jeans) | Rate (%) | GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e/Pair of Jeans) | Rate (%) | |

| Fabric production | 8.79 | 66.9 | 4.28 | 25.6 |

| Jeans production | 2.07 | 15.8 | 1.25 | 7.5 |

| Laundry | 3.18 | 24.2 | 1.13 × 101 | 67.6 |

| Disposal | −9.01 × 10−1 | −6.9 | −1.25 × 10−1 | −0.7 |

| Total | 1.31 × 101 | 100 | 1.67 × 101 | 100 |

| Author | GHG Emissions (kg-CO2e/kg-Fiber) | Region |

|---|---|---|

| Aid by Trade Foundation [27] | 1.24 | Africa |

| Cotton Incorporated [29] | 1.33 | Global mean (China, India, US, Australia) |

| Visser et al. [24] | 1.42 | Australia |

| Cotton Incorporated [28] | 1.81 | Global mean (China, India, US) |

| van der Velden et al. [19] | 3.47 | China |

| Khabbaz et al. [23] | 3.8 | Australia |

| Günther et al. [20] | 4.43 | Xinjiang, China |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Semba, T.; Furukawa, R.; Itsubo, N. Carbon Footprint for Jeans’ Circular Economy Model Using Bagasse. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146044

Semba T, Furukawa R, Itsubo N. Carbon Footprint for Jeans’ Circular Economy Model Using Bagasse. Sustainability. 2024; 16(14):6044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146044

Chicago/Turabian StyleSemba, Toshiro, Ryuzo Furukawa, and Norihiro Itsubo. 2024. "Carbon Footprint for Jeans’ Circular Economy Model Using Bagasse" Sustainability 16, no. 14: 6044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146044

APA StyleSemba, T., Furukawa, R., & Itsubo, N. (2024). Carbon Footprint for Jeans’ Circular Economy Model Using Bagasse. Sustainability, 16(14), 6044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146044