The Plastic-Reduction Behavior of Chinese Residents: Survey, Model, and Impact Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Data

2.1. Hypothesis Development

2.1.1. Environmental Values

2.1.2. Environmental Knowledge and Environmental Concern

2.1.3. Environmental Skills and Environmental Responsibility

2.1.4. Situational Variables

2.1.5. Behavioral Intention

2.2. Measures and Analytical Approach

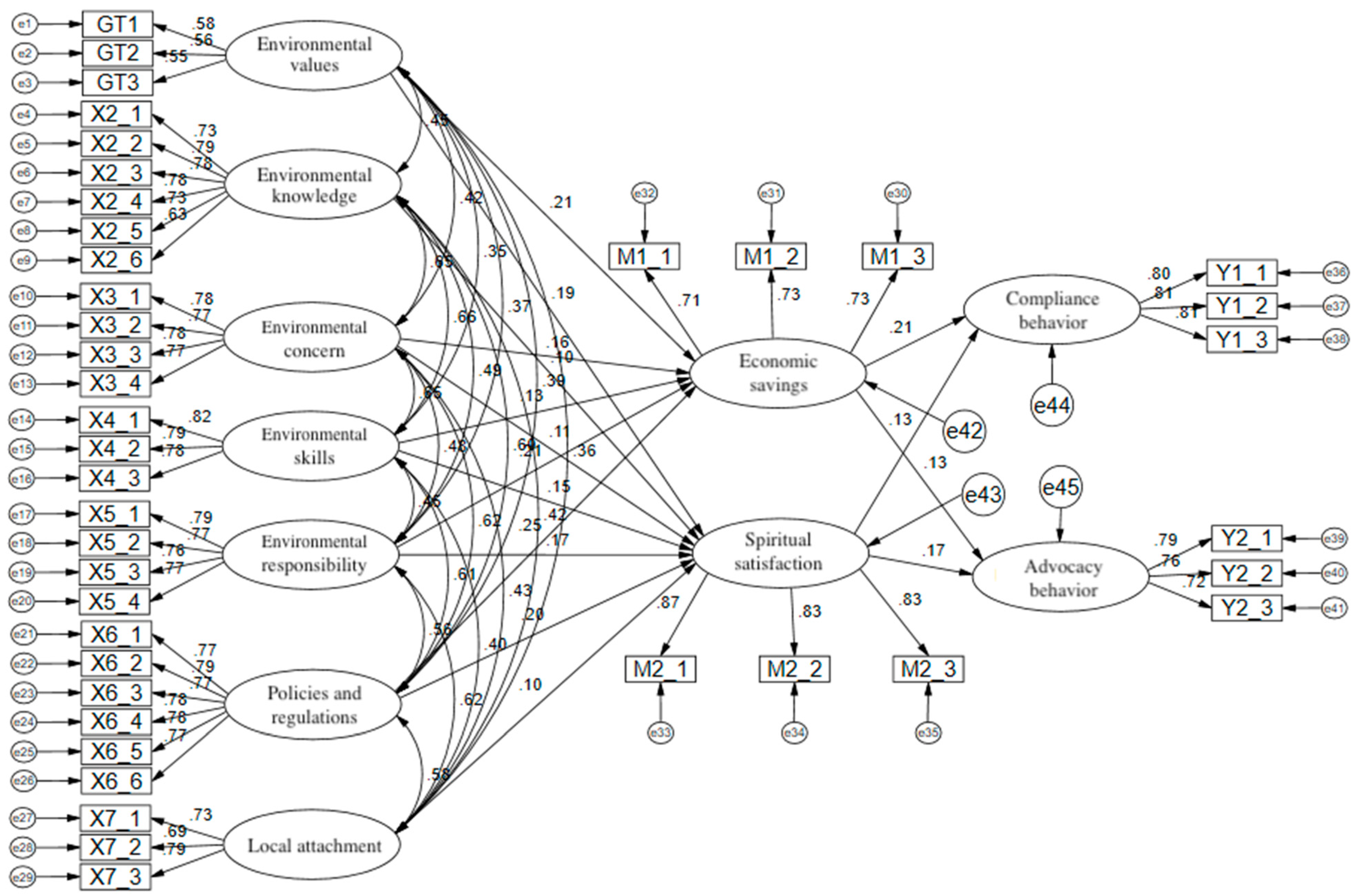

2.3. Measurement Model Test

2.4. Model Fit and Model Revision

3. Results

3.1. Structural Results

3.2. Mediation-Effect Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Quantitative Analysis of Influencing Factors Based on Behavioral Intention

4.2. Differences between Environmental Knowledge and Skills in the Behavior of Plastic Reduction

4.3. The Promotion of Local Attachment to Plastic-Reduction Behavior

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Questionnaire for Individual Environmental Behavioral on Plastic Usage and Consumption

Appendix A.1.1. Part I: Individual Plastic Consumption, Use, and Disposal Behavior

| Do You Agree with the Following Statements? Please Choose the Option That Best Reflects Your True Thoughts: | Strongly Disagree | Disagree Somewhat | Neutral | Agree Somewhat | Strongly Agree | |

| 1-1 | Engaging in environmental protection activities would make my life more meaningful. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1-2 | If I have time, I would be willing to participate in public environmental protection activities. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1-3 | I am willing to recommend eco-friendly alternatives (such as reusable bags, glass water bottles, stainless steel utensils) to others. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1-4 | If conditions allow, I am willing to choose public transportation for travel. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1-5 | When purchasing items of the same quality, I don’t mind if the packaging is not fancy. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1-6 | Whenever possible, I am open to reusing plastic products. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Have you Engaged in the Following Behaviors? Please Choose the Option That Best Reflects Your Personal Situation: | Never | Occasionally | Half of the Time | Most of the Time | Every Time | |

| 1-7 | I rarely use disposable products at home, such as disposable bowls, utensils, cups, and toiletries. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1-8 | I practice garbage sorting when disposing of waste. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1-9 | I bring my own shopping bag when going out for shopping. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1-10 | I share environmental knowledge with family, neighbors, and friends. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1-11 | I have participated in volunteer activities for beach garbage clean-up. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1-12 | I have openly expressed support for plastic reduction or voluntarily explained the pollution caused by plastic to others. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Appendix A.1.2. Part II: Personal Influencing Factors

| Please Select How Important the Following Is to You | Very Unimportant | Unimportant | Uncertain | Important | Very Important | |

| 2-1 | Personal Power | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-2 | Personal Wealth | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-3 | Personal Social Status | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-4 | Having Influence | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-5 | Social Justice | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-6 | Others’ Interests | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-7 | Social Equity | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-8 | Environmental Protection | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-9 | Preventing Pollution | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-10 | Respecting the Earth | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-11 | Living in Harmony with Nature | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Do You Have Knowledge about the Following Statements? Please Choose the Option That Best Reflects Your Understanding: | Not Familiar at All | Not Familiar | Uncertain | Familiar | Very Familiar | |

| 2-12 | Plastics cause environmental pollution due to their long degradation period. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-13 | Plastics are more challenging to handle properly when they enter the ocean compared to being on land. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-14 | Marine plastics refer to plastics that enter the ocean and cause pollution. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Are you aware of the following causes of marine plastic pollution? | ||||||

| 2-15 | Coastal tourism, aquaculture, maritime operations, and other activities. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-16 | Extensive use of plastics. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-17 | Disposal of plastics without proper consideration. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Do You Have the Following Thoughts or Behaviors? Please Choose the Option That Best Reflects Your Situation: | Never | Rarely | Occasionally | Frequently | Always | |

| 2-18 | I proactively pay attention to ocean pollution issues. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-19 | I am very concerned about the harm of marine plastics to marine animals. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-20 | I am worried about the situation of beach litter in the city where I live. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-21 | I frequently follow news reports on beach cleaning efforts or environmental news. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Have You Done the Following Behaviors? Please Choose the Option That Best Reflects Your Situation: | Never | Occasionally | Half the Time | Most of the Time | Every Time | |

| 2-22 | I can easily complete the garbage classification work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-23 | I put hazardous waste such as used fluorescent lamps, waste circuit boards, expired medicines, etc., into designated recycling bins. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-24 | I know that different types of plastics have different uses (such as food-grade plastics, microwave-specific plastics, industrial plastics). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Do You Agree with the Following Statements? Please Choose the Option that Best Reflects Your Thoughts: | Strongly Disagree | Disagree Somewhat | Neutral | Agree Somewhat | Strongly Agree | |

| 2-25 | I have a responsibility to protect the environment, and I am even willing to sacrifice some personal interests for this. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-26 | Protecting the environment and solving environmental problems is the responsibility of the government and businesses. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-27 | As long as I am willing to do my best, I can improve or solve certain environmental problems. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2-28 | The actions we take as ordinary people can also influence the government’s resolution of environmental issues. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Appendix A.1.3. Part III: Environmental Impact Factors

| Do You Agree with the Following Statements? Please Choose the Option That Best Reflects Your Thoughts: | Strongly Disagree | Disagree Somewhat | Neutral | Agree Somewhat | Strongly Agree | |

| 3-1 | If there are volunteer activities similar to “Ocean Guardian”, I am willing to contribute. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3-2 | If there are rewards for recycling old plastic and picking up beach litter, I would collect garbage and participate in recycling. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3-3 | I would like to have titles such as “Eco Pioneer” or “Ocean Guardian”. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Do You Agree with the Following Statements? Please Choose the Option That Best Reflects Your Thoughts: | Strongly Disagree | Disagree Somewhat | Neutral | Agree Somewhat | Strongly Agree | |

| 3-4 | If the supermarket charges for plastic bags, I will remember to bring my shopping bag and remind others. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3-5 | If fines are imposed in coastal areas, I will pay extra attention to whether I behave uncivilized. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3-6 | If someone reminds me at the garbage sorting point or in places like supermarkets, I can better complete garbage classification and recycling and reduce the purchase of plastic products. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Do You Agree with the Following Statements? Please Choose the Option That Best Reflects Your Thoughts: | Strongly Disagree | Disagree Somewhat | Neutral | Agree Somewhat | Strongly Agree | |

| 3-7 | I prefer living in the current city compared to other cities. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3-8 | I strongly agree with the city image created by the current city. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3-9 | The scenery and landscapes of the city can add beauty to my life. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ≤Open-ended questions: | |

|

Appendix B

| Component | Initial Eigenvalue | Extracted Sum of Squared Loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Variance Percentage | Cumulative% | Total | Variance Percentage | Cumulative% | |

| 1 | 13.718 | 27.997 | 27.997 | 13.718 | 27.997 | 27.997 |

| 2 | 4.214 | 8.6 | 36.596 | 4.214 | 8.6 | 36.596 |

| 3 | 2.348 | 4.792 | 41.389 | 2.348 | 4.792 | 41.389 |

| 4 | 2.294 | 4.681 | 46.07 | 2.294 | 4.681 | 46.07 |

| 5 | 1.97 | 4.021 | 50.091 | 1.97 | 4.021 | 50.091 |

| 6 | 1.855 | 3.786 | 53.877 | 1.855 | 3.786 | 53.877 |

| 7 | 1.673 | 3.415 | 57.291 | 1.673 | 3.415 | 57.291 |

| 8 | 1.595 | 3.256 | 60.547 | 1.595 | 3.256 | 60.547 |

| 9 | 1.403 | 2.864 | 63.411 | 1.403 | 2.864 | 63.411 |

| 10 | 1.247 | 2.545 | 65.956 | 1.247 | 2.545 | 65.956 |

| 11 | 1.171 | 2.39 | 68.346 | 1.171 | 2.39 | 68.346 |

| 12 | 1.147 | 2.34 | 70.687 | 1.147 | 2.34 | 70.687 |

| 13 | 1.017 | 2.076 | 72.762 | 1.017 | 2.076 | 72.762 |

| Variable | Normality Test | Reliability | Convergent Validity | Discriminant Validity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructs | Items | AVG | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | Standardized Factor Load | CR | AVE | HTMT | |

| Environmental values (EV) | Egoistic values | GT1_1 | 3.58 | 1.172 | −0.397 | −0.843 | 0.878 | 0.778 | 0.879 | 0.646 | 0.804 |

| GT1_2 | 3.61 | 1.259 | −0.444 | −0.971 | 0.861 | ||||||

| GT1_3 | 3.57 | 1.069 | −0.381 | −0.516 | 0.770 | ||||||

| GT1_4 | 3.56 | 1.193 | −0.487 | −0.732 | 0.803 | ||||||

| Altruistic values | GT2_1 | 3.28 | 1.096 | −0.044 | −0.783 | 0.906 | 0.913 | 0.908 | 0.766 | 0.875 | |

| GT2_2 | 3.26 | 1.205 | −0.141 | −1.043 | 0.867 | ||||||

| GT2_3 | 3.24 | 1.063 | −0.004 | −0.764 | 0.844 | ||||||

| Ecological values | GT3_1 | 3.49 | 1.289 | −0.437 | −0.941 | 0.905 | 0.874 | 0.906 | 0.706 | 0.840 | |

| GT3_2 | 3.47 | 1.317 | −0.294 | −1.173 | 0.853 | ||||||

| GT3_3 | 3.45 | 1.247 | −0.374 | −0.939 | 0.803 | ||||||

| GT3_4 | 3.39 | 1.342 | −0.358 | −1.086 | 0.829 | ||||||

| Environmental knowledge (EK) | X2_1 | 3.14 | 1.027 | −0.207 | −0.383 | 0.840 | 0.734 | 0.881 | 0.554 | 0.744 | |

| X2_2 | 3.16 | 1.055 | −0.244 | −0.424 | 0.792 | ||||||

| X2_3 | 3.16 | 1.007 | −0.273 | −0.208 | 0.784 | ||||||

| X2_4 | 3.23 | 1.127 | −0.222 | −0.696 | 0.784 | ||||||

| X2_5 | 3.18 | 1.005 | −0.270 | −0.165 | 0.731 | ||||||

| X2_6 | 3.07 | 0.915 | −0.051 | 0.072 | 0.629 | ||||||

| Environmental concern (EC) | X3_1 | 3.20 | 1.311 | −0.193 | −1.171 | 0.881 | 0.784 | 0.858 | 0.601 | 0.775 | |

| X3_2 | 3.22 | 1.338 | −0.291 | −1.104 | 0.770 | ||||||

| X3_3 | 3.12 | 1.297 | −0.180 | −1.157 | 0.776 | ||||||

| X3_4 | 3.18 | 1.347 | −0.245 | −1.153 | 0.770 | ||||||

| Environmental skills (ES) | X4_1 | 3.41 | 1.344 | −0.470 | −1.024 | 0.858 | 0.820 | 0.839 | 0.636 | 0.797 | |

| X4_2 | 3.39 | 1.278 | −0.288 | −1.169 | 0.787 | ||||||

| X4_3 | 3.32 | 1.340 | −0.287 | −1.175 | 0.785 | ||||||

| Environmental responsibility (ER) | X5_1 | 3.43 | 1.343 | −0.447 | −1.022 | 0.856 | 0.793 | 0.856 | 0.598 | 0.773 | |

| X5_2 | 3.37 | 1.321 | −0.478 | −0.933 | 0.769 | ||||||

| X5_3 | 3.41 | 1.328 | −0.413 | −1.034 | 0.758 | ||||||

| X5_4 | 3.47 | 1.324 | −0.458 | −0.990 | 0.773 | ||||||

| Policies and regulations (PR) | X6_1 | 3.40 | 1.318 | −0.418 | −1.025 | 0.900 | 0.774 | 0.900 | 0.601 | 0.775 | |

| X6_2 | 3.40 | 1.340 | −0.413 | −1.061 | 0.790 | ||||||

| X6_3 | 3.35 | 1.340 | −0.432 | −1.036 | 0.767 | ||||||

| X6_4 | 3.44 | 1.304 | −0.438 | −0.992 | 0.775 | ||||||

| X6_5 | 3.38 | 1.307 | −0.404 | −1.027 | 0.775 | ||||||

| X6_6 | 3.40 | 1.307 | −0.444 | −0.969 | 0.768 | ||||||

| Local attachment (LA) | X7_1 | 3.33 | 1.251 | −0.334 | −0.943 | 0.848 | 0.729 | 0.779 | 0.541 | 0.736 | |

| X7_2 | 3.33 | 1.260 | −0.456 | −0.883 | 0.690 | ||||||

| X7_3 | 3.29 | 1.223 | −0.308 | −0.935 | 0.785 | ||||||

| Economic savings (EcoS) | M1_1 | 3.37 | 1.277 | −0.311 | −1.042 | 0.780 | 0.708 | 0.768 | 0.525 | 0.725 | |

| M1_2 | 3.42 | 1.197 | −0.411 | −0.879 | 0.733 | ||||||

| M1_3 | 3.40 | 1.247 | −0.328 | −1.006 | 0.733 | ||||||

| Spiritual satisfaction (SS) | M2_1 | 3.34 | 0.920 | −0.426 | 0.020 | 0.767 | 0.866 | 0.882 | 0.714 | 0.845 | |

| M2_2 | 3.35 | 0.901 | −0.521 | 0.250 | 0.833 | ||||||

| M2_3 | 3.32 | 0.870 | −0.289 | 0.279 | 0.835 | ||||||

| Compliance with plastic reduction behavior (CB) | Y1_1 | 3.56 | 0.970 | −0.703 | 0.288 | 0.881 | 0.804 | 0.848 | 0.651 | 0.807 | |

| Y1_2 | 3.50 | 0.977 | −0.386 | −0.169 | 0.807 | ||||||

| Y1_3 | 3.47 | 0.945 | −0.378 | 0.031 | 0.810 | ||||||

| Advocacy for plastic reduction behavior (AB) | Y2_1 | 3.60 | 1.033 | −0.472 | −0.293 | 0.804 | 0.796 | 0.804 | 0.578 | 0.760 | |

| Y2_2 | 3.49 | 1.012 | −0.387 | −0.309 | 0.749 | ||||||

| Y2_3 | 3.49 | 0.975 | −0.325 | −0.205 | 0.734 | ||||||

References

- van Sebille, E.; Wilcox, C.; Lebreton, L.; Maximenko, N.; Hardesty, B.D.; van Franeker, J.A.; Eriksen, M.; Siegel, D.; Galgani, F.; Law, K.L. A Global Inventory of Small Floating Plastic Debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 124006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, P.; Xu, R.; Wang, X.; Lei, L.; Schartup, A.T.; Peng, Y.; Pang, Q.; Wang, X.; Mai, L.; et al. Plastic Waste Discharge to the Global Ocean Constrained by Seawater Observations. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelle, S.B.; Ringma, J.; Law, K.L.; Monnahan, C.C.; Lebreton, L.; McGivern, A.; Murphy, E.; Jambeck, J.; Leonard, G.H.; Hilleary, M.A.; et al. Predicted Growth in Plastic Waste Exceeds Efforts to Mitigate Plastic Pollution. Science 2020, 369, 1515–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Almeida, M.; Miguel, I. A Micro(Nano)Plastic Boomerang Tale: A Never Ending Story? TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 112, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Almeida, M. The Why and How of Micro(Nano)Plastic Research. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 114, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.A.; Prasetya, T.A.E.; Dewi, I.R.; Ahmad, M. Microplastics in Human Food Chains: Food Becoming a Threat to Health Safety. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, N.J.; Aanesen, M.; Austen, M.C.; Börger, T.; Clark, J.R.; Cole, M.; Hooper, T.; Lindeque, P.K.; Pascoe, C.; Wyles, K.J. Global Ecological, Social and Economic Impacts of Marine Plastic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 142, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, M.R. Environmental Implications of Plastic Debris in Marine Settings—Entanglement, Ingestion, Smothering, Hangers-on, Hitch-Hiking and Alien Invasions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2013–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, A.; Ross, H.; Setianto, N.A.; Fielding, K.; Pradipta, L. Ocean Plastic Crisis—Mental Models of Plastic Pollution from Remote Indonesian Coastal Communities. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoca, M.S.; McInturf, A.G.; Hazen, E.L. Plastic Ingestion by Marine Fish Is Widespread and Increasing. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 2188–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIlgorm, A.; Raubenheimer, K.; McIlgorm, D.E.; Nichols, R. The Cost of Marine Litter Damage to the Global Marine Economy: Insights from the Asia-Pacific into Prevention and the Cost of Inaction. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 174, 113167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolahpur Monikh, F.; Holm, S.; Kortet, R.; Bandekar, M.; Kekäläinen, J.; Koistinen, A.; Leskinen, J.T.T.; Akkanen, J.; Huuskonen, H.; Valtonen, A.; et al. Quantifying the Trophic Transfer of Sub-Micron Plastics in an Assembled Food Chain. Nano Today 2022, 46, 101611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, R.; Fang, Q. Marine Plastic Management Policy Agenda-Setting in China (1985–2021): The Multi-Stage Streams Framework. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 243, 106761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Elsamahy, T.; Koutra, E.; Kornaros, M.; El-Sheekh, M.; Abdelkarim, E.A.; Zhu, D.; Sun, J. Degradation of Conventional Plastic Wastes in the Environment: A Review on Current Status of Knowledge and Future Perspectives of Disposal. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiu, M.K.; Jaeger-Erben, M. Reducing Single-Use Plastic in Everyday Social Practices: Insights from a Living Lab Experiment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 200, 107303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevi, M.R.; Suhartanto, D. The Integrated Model of Green Loyalty: Evidence from Eco-Friendly Plastic Products. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, P.G.; Chitaka, T.Y. Do We Need More Research on the Environmental Impacts of Plastics? Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 090201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, X. Show Me the Impact: Communicating “Behavioral Impact Message” to Promote pro-Environmental Consumer Behavior. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 35, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidbreder, L.M.; Bablok, I.; Drews, S.; Menzel, C. Tackling the Plastic Problem: A Review on Perceptions, Behaviors, and Interventions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.; Miguel, I.; Venâncio, C.; Lopes, I.; Oliveira, M. Public Views on Plastic Pollution: Knowledge, Perceived Impacts, and pro-Environmental Behaviours. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, D.G. Values and Their Effect on Pro-Environmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 1996, 28, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.; Choi, J. Antecedents and Interrelationships of Three Types of Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Values, Environmental Concern, and Environmental Behavior: A Study into Household Energy Use. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crumpei, I.; Boncu, S.; Crumpei, G. Environmental Attitudes and Ecological Moral Reasoning in Romanian Students. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 114, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schahn, J.; Holzer, E. Studies of Individual Environmental Concern: The Role of Knowledge, Gender, and Background Variables. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Saengon, P.; Alganad, A.M.N.; Chongcharoen, D.; Farrukh, M. Consumer Green Behaviour: An Approach towards Environmental Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1168–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umuhire, M.L.; Fang, Q. Method and Application of Ocean Environmental Awareness Measurement: Lessons Learnt from University Students of China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 102, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Zhu, H. Influence of Multi-Dimensional Environmental Knowledge on Residents’ Waste Sorting Intention: Moderating Effect of Environmental Concern. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 957683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, P.; Guo, G.; Zhang, W. The Role of Social Influence in Green Travel Behavior in Rural China. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 107, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalu, M.T.B.; Cuthbert, R.N.; Muhali, H.; Chari, L.D.; Manyani, A.; Masunungure, C.; Dalu, T. Is Awareness on Plastic Pollution Being Raised in Schools? Understanding Perceptions of Primary and Secondary School Educators. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and Synthesis of Research on Responsible Environmental Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Qi, Z.; Wu, L.; Hu, J. The impact of farmers’ environmental awareness on environmentally friendly behavior: The moderating effect of community environment. J. Chin. Agric. Univ. 2016, 21, 155–164. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour: An Integrative Review and Research Agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodur, M.; Sarigöllü, E. Environmental Sensitivity in a Developing Country: Consumer Classification and Implications. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.D.; Mathur, A. Plastic Pollution in India: An Evaluation of Public Awareness and Consumption Behaviour. OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 12, 25–40. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3548729 (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Wang, W.; Li, X.; Li, H. Empirical Research of the Environmental Responsibility Affected on the Urban Residential Housing Energy Saving Investment Behavior. Energy Procedia 2011, 5, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Liu, X. Pro-Environmental Behavior Research: Theoretical Progress and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Gong, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y. Effects of Monetary and Nonmonetary Incentives in Individual Low-Carbon Behavior Rewarding System on Recycling Behaviors: The Role of Perceived Environmental Responsibility. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Cai, X. The Implementation Effects of Different Plastic Bag Ban Policies in China: The Role of Consumers’ Involvement. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 041002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Park, I.K. The Effects of Regional Characteristics and Policies on Individual Pro-Environmental Behavior in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.H.; Polonsky, M.J.; McClaren, N. Reducing Plastic Pollution Using Norms Perspective: Integration of Moral Position and Place Attachment. In Socially Responsible Plastic: Is This Possible? Emerald Publishing Limited: Bentley, UK, 2023; pp. 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, C.C.; Dao, A.T.; Doan, N.K.T. The Role of Social Factors and Community Attachment in the Intention to Reduce Plastic Bag Consumption and Pro-Environmental Behaviors. J. Human Behav. Soc. Environ. 2023, 34, 752–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyawe, H. Place Attachment and Pro-Environmental Behaviour Paralysis: A Study of Household Solid Waste Management. J. Constr. Proj. Manag. Innov. 2019, 9, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Guo, D.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z. Analysis of Factors Influencing Residents’ Habitual Energy-Saving Behaviour Based on NAM and TPB Models: Egoism or Altruism? Energy Policy 2018, 116, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Broek, K.L.; Walker, I. Exploring the Perceptions of Drivers of Energy Behaviour. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviste, R.P.; Niemiec, C.P. Antecedents of Environmental Values and Pro-Environmental Behavior Intentions: A Self-Determination Theory Approach. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 88, 102023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yang, H.; Ling, M. Interpersonal Contextual Influences on the Relationship between Values and Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbeide, O.A.; Ford, C.; Stringer, R. The Environmental Benefits of Organic Wine: Exploring Consumer Willingness-to-Pay Premiums? J. Food Prod. Mark. 2015, 21, 482–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosdahl, D.J.; Carpenter, J.M. Consumer Knowledge of the Environmental Impacts of Textile and Apparel Production, Concern for the Environment, and Environmentally Friendly Consumption Behavior. J. Text. Appar. Technol. Manag. 2010, 6, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Tomiuk, M.-A.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Cultural Differences in Environmental Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours of Canadian Consumers. Can. J. Adm. Sci./Rev. Can. Sci. Adm. 2002, 19, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Head, B.W. Determinants of Young Australians’ Environmental Actions: The Role of Responsibility Attributions, Locus of Control, Knowledge and Attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.S.; Strube, M.J. Environmental Attitudes, Knowledge, Intentions and Behaviors among College Students. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 152, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How Does Environmental Knowledge Translate into Pro-Environmental Behaviors?: The Mediating Role of Environmental Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poortinga, W.; Spence, A.; Demski, C.; Pidgeon, N.F. Individual-Motivational Factors in the Acceptability of Demand-Side and Supply-Side Measures to Reduce Carbon Emissions. Energy Policy 2012, 48, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Long, R. Analysis of the Influencing Factors of the Public Willingness to Participate in Public Bicycle Projects and Intervention Strategies-A Case Study of Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, N. Providing New Environmental Skills for British Farmers. J. Environ. Manag. 1997, 50, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurin, R.R.; Roush, D.; Danter, K.J. Environmental Communication, 2nd ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; ISBN 978-90-481-3986-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Value Structures behind Proenvironmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Scheuthle, H. Two Challenges to a Moral Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior: Moral Norms and Just World Beliefs in Conservationism. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2003, 35, 1033–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. Behavioural Responses to Climate Change: Asymmetry of Intentions and Impacts. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, K.; Lennox, A.; Kaufman, S.; Tull, F.; Prime, R.; Rogers, L.; Dunstan, E. Curbing Plastic Consumption: A Review of Single-Use Plastic Behaviour Change Interventions. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 344, 131077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zheng, J.; Fang, Q. How a Typhoon Event Transforms Public Risk Perception of Climate Change: A Study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Martín, A.M.; Ruiz, C.; Hidalgo, M.d.C. The Role of Place Identity and Place Attachment in Breaking Environmental Protection Laws. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fano, D.; Schena, R.; Russo, A. Empowering Plastic Recycling: Empirical Investigation on the Influence of Social Media on Consumer Behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Human Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Foxall, G.R.; Pallister, J. Beyond the Intention–Behaviour Mythology: An Integrated Model of Recycling. Mark. Theory 2002, 2, 29–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.; Kaiser, F.G. Promoting Pro-Environmental Behavior. Oxf. Handb. Environ. Conserv. Psychol. Oxf. Libr. Psychol. 2012, 556–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, M.; Bruns, H.; DellaValle, N.; Murauskaite-Bull, I. Synergies of Interventions to Promote Pro-Environmental Behaviors–A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2024, 84, 102776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Allen, M. Understanding Pro-Environmental Behavior: Models and Messages. Strateg. Commun. Sustain. Organ. Theory Pract. 2016, 2016, 105–137. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 0135153093. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B. Building a Science of Motivated Persons: Self-Determination Theory’s Empirical Approach to Human Experience and the Regulation of Behavior. Motiv. Sci. 2021, 7, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, I.; White, M.P.; Pahl, S.; Duarte-Davidson, R.; Fleming, L.E. Associations between Pro-Environmental Behaviour and Neighbourhood Nature, Nature Visit Frequency and Nature Appreciation: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey in England. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; White, M.P.; Hunt, A.; Richardson, M.; Pahl, S.; Burt, J. Nature Contact, Nature Connectedness and Associations with Health, Wellbeing and pro-Environmental Behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Indicators | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral intention | Spiritual satisfaction (SS) | 1-1~1-3 | [62] |

| Economic savings (EcoS) | 1-4~1-6 | [63] | |

| Behavior | Compliance behavior (CB) | 1-7~1-9 | [40] |

| Advocacy behavior (AB) | 1-10~1-12 | [64] | |

| Internal individual factor | Environmental values (EV) | 2-1~2-11 | [65,66] |

| Environmental knowledge (EK) | 2-12~2-17 | [67] | |

| Environmental concern (EC) | 2-18~2-21 | [67] | |

| Environmental skills (ES) | 2-22~2-24 | [45] | |

| Environmental responsibility (ER) | 2-25~2-28 | [62] | |

| External environment factor | Policies and regulations (PR) | 3-1~3-6 | [68] |

| Local attachment (LA) | 3-7~3-9 | [69] |

| Hypothesis and Path | β | b | S.E. | C.R. | p | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a EV → EcoS | 0.201 | 0.312 | 0.08 | 3.891 | *** | YES |

| H1b EV → SS | 0.188 | 0.257 | 0.061 | 4.205 | *** | YES |

| H2a EK → EcoS | −0.018 | −0.021 | 0.066 | −0.325 | 0.745 | NO |

| H2b EK → SS | 0.100 | 0.105 | 0.05 | 2.1 | 0.036 * | YES |

| H2c EC → EcoS | 0.169 | 0.149 | 0.049 | 3.04 | 0.002 ** | YES |

| H2d EC → SS | 0.106 | 0.082 | 0.037 | 2.226 | 0.026 * | YES |

| H3a ES → EcoS | 0.144 | 0.119 | 0.046 | 2.589 | 0.010 * | YES |

| H3b ES → SS | 0.145 | 0.105 | 0.035 | 3.019 | 0.003 ** | YES |

| H3c ER → EcoS | 0.169 | 0.126 | 0.032 | 3.879 | *** | YES |

| H3d ER → SS | 0.175 | 0.149 | 0.043 | 3.474 | *** | YES |

| H4a PR → EcoS | 0.227 | 0.202 | 0.049 | 4.141 | *** | YES |

| H4b PR → SS | 0.195 | 0.153 | 0.037 | 4.141 | *** | YES |

| H4c LA → EcoS | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.053 | 1.418 | 0.156 | NO |

| H4d LA → SS | 0.104 | 0.091 | 0.04 | 2.283 | 0.022 * | YES |

| H5a EcoS → CB | 0.210 | 0.178 | 0.045 | 3.972 | *** | YES |

| H5b EcoS → AB | 0.130 | 0.101 | 0.042 | 2.392 | 0.017 * | YES |

| H5c SS → CB | 0.131 | 0.126 | 0.048 | 2.623 | 0.009 ** | YES |

| H5d SS → AB | 0.169 | 0.149 | 0.046 | 3.265 | 0.001 ** | YES |

| Index | c2/df | RMSEA | GFI | CFI | IFI | TLI | AGFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norm * | 1 < c2/df < 5 | <0.080 | >0.800 | >0.800 | >0.800 | >0.800 | >0.800 |

| The initial model | |||||||

| Value | 2.082 | 0.035 | 0.921 | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.951 | 0.908 |

| Judgment | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| The revised model | |||||||

| Value | 2.079 | 0.035 | 0.921 | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.951 | 0.909 |

| Judgment | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hypothesis and Path | β | b | S.E. | C.R. | p | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a EV → EcoS | 0.206 | 0.319 | 0.078 | 4.112 | *** | YES |

| H1b EV → SS | 0.188 | 0.257 | 0.061 | 4.203 | *** | YES |

| H2b EK → SS | 0.100 | 0.106 | 0.050 | 2.125 | 0.034 * | YES |

| H2c EC → EcoS | 0.163 | 0.144 | 0.048 | 3.019 | 0.003 ** | YES |

| H2d EC → SS | 0.106 | 0.082 | 0.037 | 2.223 | 0.026 * | YES |

| H3a ES → EcoS | 0.134 | 0.110 | 0.043 | 2.578 | 0.010 * | YES |

| H3b ES → SS | 0.145 | 0.105 | 0.035 | 3.015 | 0.003 ** | YES |

| H3c ER → EcoS | 0.169 | 0.127 | 0.032 | 3.895 | *** | YES |

| H3d ER → SS | 0.208 | 0.176 | 0.038 | 4.696 | *** | YES |

| H4a PR → EcoS | 0.251 | 0.223 | 0.046 | 4.882 | *** | YES |

| H4b PR → SS | 0.196 | 0.153 | 0.037 | 4.153 | *** | YES |

| H4d LA → SS | 0.102 | 0.089 | 0.040 | 2.229 | 0.026 * | YES |

| H5a EcoS → CB | 0.212 | 0.180 | 0.045 | 4.017 | *** | YES |

| H5b EcoS → AB | 0.130 | 0.101 | 0.042 | 2.399 | 0.016 * | YES |

| H5c SS → CB | 0.130 | 0.125 | 0.048 | 2.609 | 0.009 ** | YES |

| H5d SS → AB | 0.169 | 0.149 | 0.046 | 3.273 | 0.001 ** | YES |

| Hypothesis and Path | Direct Effect | S.E. | 95% Lower Limit | 95% Upper Limit | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EV → EcoS → CB | 0.057 | 0.028 | 0.017 | 0.127 | 0.000 |

| EV → EcoS → AB | 0.032 | 0.020 | 0.003 | 0.085 | 0.020 |

| EC → EcoS → CB | 0.026 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.057 | 0.002 |

| EC → EcoS → AB | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.038 | 0.017 |

| ES → EcoS → CB | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.044 | 0.006 |

| ES → EcoS → AB | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.019 |

| ER → EcoS → CB | 0.032 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.059 | 0.000 |

| ER → EcoS → AB | 0.018 | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.039 | 0.015 |

| PR → EcoS → CB | 0.040 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.076 | 0.000 |

| PR → EcoS → AB | 0.023 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.050 | 0.016 |

| EV → SS → CB | 0.032 | 0.020 | 0.003 | 0.081 | 0.030 |

| EV → SS → AB | 0.038 | 0.019 | 0.010 | 0.086 | 0.004 |

| EK → SS → CB | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.039 | 0.031 |

| EK → SS → AB | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.041 | 0.023 |

| EC → SS → CB | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.029 |

| EC → SS → AB | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.031 | 0.012 |

| ES → SS → CB | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.033 | 0.022 |

| ES → SS → AB | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.035 | 0.003 |

| ER → SS → CB | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.037 | 0.020 |

| ER → SS → AB | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.040 | 0.003 |

| PR → SS → CB | 0.019 | 0.010 | 0.003 | 0.044 | 0.021 |

| PR → SS → AB | 0.023 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.048 | 0.003 |

| LA → SS → CB | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.033 | 0.025 |

| LA → SS → AB | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.036 | 0.012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Yang, R.; Bai, P.; Fang, Q.; Jiang, X. The Plastic-Reduction Behavior of Chinese Residents: Survey, Model, and Impact Factors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146093

Wang B, Yang R, Bai P, Fang Q, Jiang X. The Plastic-Reduction Behavior of Chinese Residents: Survey, Model, and Impact Factors. Sustainability. 2024; 16(14):6093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146093

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Boyu, Ronggang Yang, Peiyuan Bai, Qinhua Fang, and Xiaoyan Jiang. 2024. "The Plastic-Reduction Behavior of Chinese Residents: Survey, Model, and Impact Factors" Sustainability 16, no. 14: 6093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146093

APA StyleWang, B., Yang, R., Bai, P., Fang, Q., & Jiang, X. (2024). The Plastic-Reduction Behavior of Chinese Residents: Survey, Model, and Impact Factors. Sustainability, 16(14), 6093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146093