Institutional Environment, Institutional Arrangements, and Risk Identification and Allocation in Public–Private Partnerships: A Multilevel Model Analysis Based on Data from 31 Provinces in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Identification and Allocation of Risk in Public–Private Partnerships

2.2. Effective Identification and Allocation of Risk as a Decision-Making Process

3. Institutional Environments, Institutional Arrangements, and Risk Identification and Allocation: A Theoretical Framework

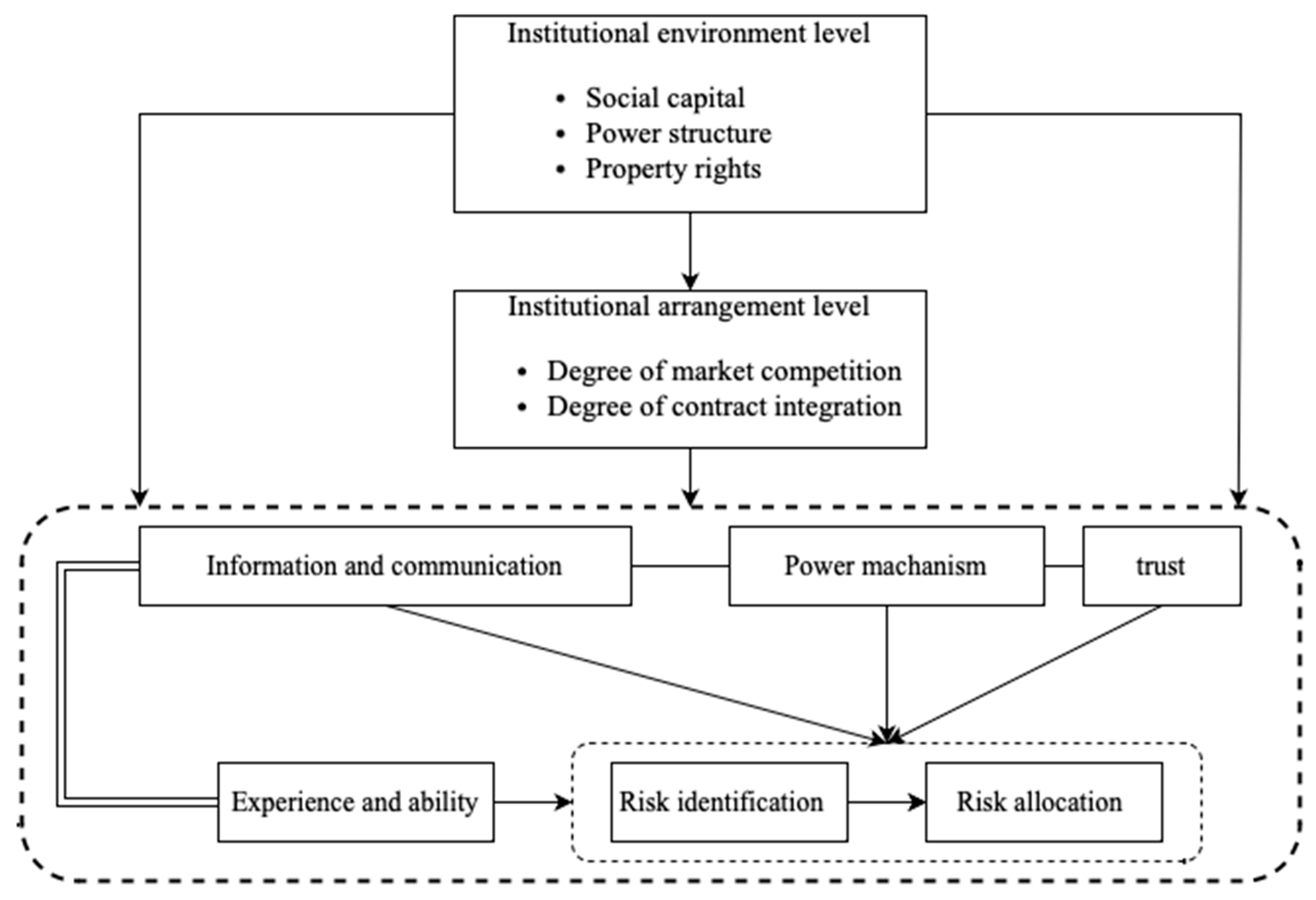

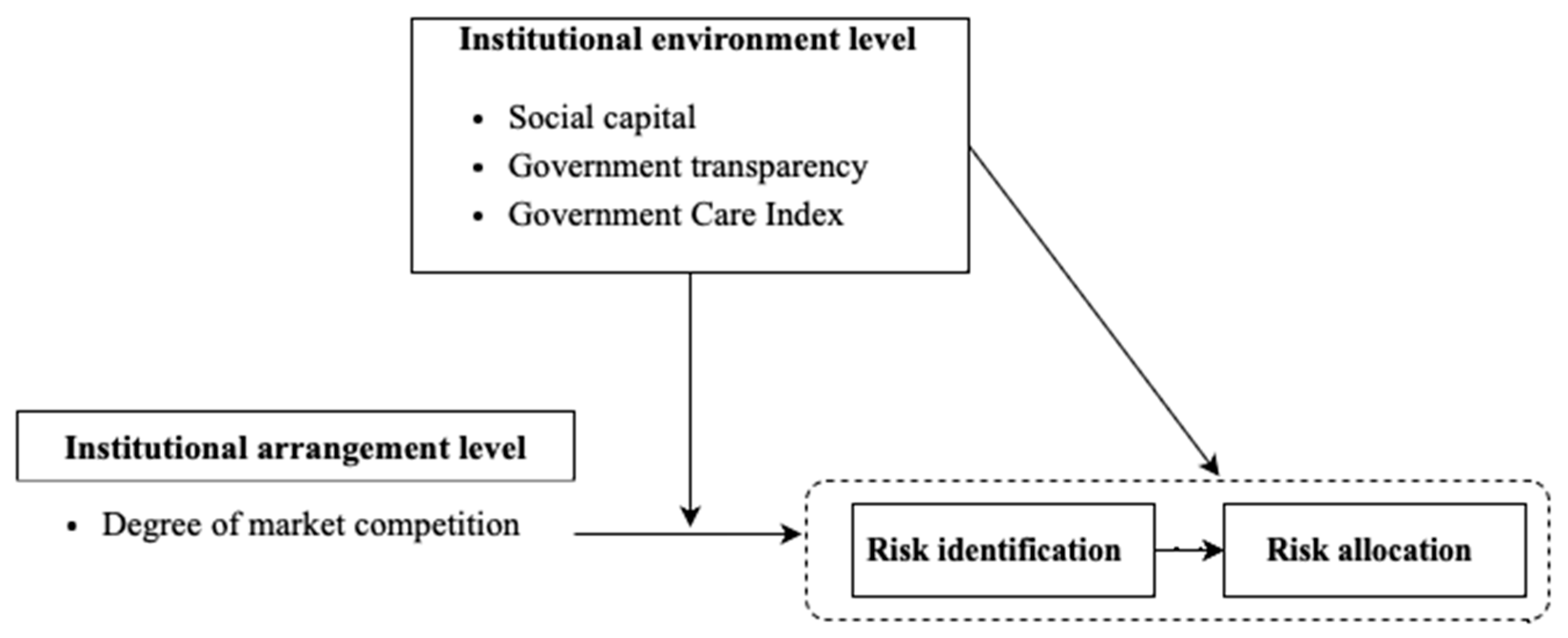

3.1. Risk Governance from an Institutional Analysis Perspective

3.2. Institutional Arrangements and Risk Identification and Allocation

3.3. Institutional Environments and Risk Identification and Allocation

3.4. Institutional Arrangements, Institutional Environment, and Risk Identification and Allocation

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Context

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Measurement

- (1)

- Dependent Variables

- (2)

- Independent Variables

- (3)

- Control Variables

4.4. Model Specification and Centering of Explanatory Variables

- (1)

- M1

- (2)

- M2

- (3)

- M3

- (4)

- M4

- (5)

- M5

5. Results

5.1. Results of Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Results of Multilevel Modeling Analysis

- (1)

- M1 (Null Model): Differences in RISK Across Provinces

- (2)

- M2 (Stochastic Coefficient Model): the Relationship between Hierarchical Variables and Project Risk

- (3)

- M3 (Intercept Model): Relationship between Provincial Level Variables and RISK

- (4)

- M4 (Context Model): the Relationship between Different Levels of Variables and RISK

- (5)

- M5 (Full Model): the Interaction of Two Levels of Variables

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hodge, G.A.; Greve, C. Public-Private Partnerships: An International Performance Review. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J. The Formation of Public-Private Partnerships: Lessons from Nine Transport Infrastructure Projects in the Netherlands. Public Adm. 2005, 83, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.F.; Enserink, B. Public-Private Partnerships in Urban Infrastructures: Reconciling Private Sector Participation and Sustainability. Public Adm. Rev. 2009, 69, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T. Public-Private Partnerships: From Contested Concepts to Prevalent Practice. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2004, 70, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrer, J.; Kee, J.E.; Newcomer, K.E.; Boyer, E. Public-Private Partnerships and the Public Accountability Question. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, G.A.; Greve, C. On Public-Private Partnership Performance: A Contemporary Review. Public Work. Manag. Policy 2017, 22, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, G.; Greve, C.; Biygautane, M. Do PPPs Work? What and How Have We Been Learning So Far? Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, E. The Not So Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Over Twelve Years of PPP in Ireland. Local Gov. Stud. 2013, 39, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, S. A Study on the Dynamic Evolution Paths of Social Risks in PPP Projects of Water Environmental Governance—From the Vulnerability Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, S.; Chan, A.P. Risk Misallocation in Public–Private Partnership Projects in China. Int. Public Manag. J. 2013, 16, 438–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.J.; Su, G.; Li, D. The Rise of Public-Private Partnerships in China. J. Chin. Gov. 2018, 3, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R.; Heafey, M.; King, D. Risk Transfer and Value for Money in PFI Projects. Public Manag. Rev. 2003, 5, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpintero, S.; Helby Petersen, O. Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) in Local Services: Risk-Sharing and Private Delivery of Water Services in Spain. Local Govt. Stud. 2016, 42, 958–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha Marques, R.; Berg, S. Public–Private Partnership Contracts: A Tale of Two Cities with Different Contractual Arrangements. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 1585–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, G.A. Risks in Public-Private Partnerships: Shifting, Sharing or Shirking? Asia Pac. J. Public Adm. 2004, 26, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsiri, N. Public-Private Partnerships in Thailand: A Case Study of the Electric Utility Industry. Public Policy Adm. 2003, 18, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ham, H.; Koppenjan, J. Building Public-Private Partnerships: Assessing and Managing Risks in Port Development. Public Manag. Rev. 2001, 3, 593–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizkorodov, E. Evaluating Risk Allocation and Project Impacts of Sustainability-Oriented Water Public–Private Partnerships in Southern California: A Comparative Case Analysis. World Dev. 2021, 140, 105232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, C.; Gomes, R.C. Public Value Creation and Appropriation Mechanisms in Public–Private Partnerships: How Does It Play a Role? Public Adm. 2023, 101, 693–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Chen, B.; Wang, H.; Zhu, D. Governing Public–Private Partnerships: A Systematic Review of Case Study Literature. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2019, 78, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.X.; Wang, S.; Fang, D. A Life-Cycle Risk Management Framework for PPP Infrastructure Projects. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2008, 13, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Chan, T.K.; Aibinu, A.A.; Chen, C.; Martek, I. Risk Allocation Inefficiencies in Chinese PPP Water Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallaki, M.; Bracci, E. Risk Allocation, Transfer and Management in Public–Private Partnership and Private Finance Initiatives: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2021, 34, 709–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsen, R.; Klijn, E.H.; Koppenjan, J. Mix and Match: How Contractual and Relational Conditions Are Combined in Successful Public–Private Partnerships. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2019, 29, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.H.; Doloi, H. Interpreting Risk Allocation Mechanism in Public–Private Partnership Projects: An Empirical Study in a Transaction Cost Economics Perspective. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2008, 26, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soecipto, R.M.; Verhoest, K. Contract Stability in European Road Infrastructure PPPs: How Does Governmental PPP Support Contribute to Preventing Contract Renegotiation? Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 1145–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalate, D.; Bel, G.; Reeves, E. Government Choice Between Contract Termination and Contract Expiration in Re-Municipalization: A Case of Historical Recurrence? Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2021, 87, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Political Influences of Stakeholders on Early Termination of Public-Private Partnerships: A Study on China’s Toll Road Projects. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2023, 46, 1354–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L.; Potoski, M. Transaction Costs and Institutional Explanations for Government Service Production Decisions. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2003, 13, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Evolution of Public–Private Partnership Models in American Toll Road Development: Learning Based on Public Institutions’ Risk Management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.; Gudergan, S.P. Governance of Public–Private Partnerships: Lessons Learnt from an Australian Case? Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2007, 73, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P. Review of Studies on the Critical Success Factors for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) Projects from 1990 to 2013. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Jin, X.; Nnaji, C.; Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Wuni, I.Y. Review of Risk Management Studies in Public-Private Partnerships: A Scientometric Analysis. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 2419–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, J. Minimising Risk: The Role of the Local Authority Risk Manager in PFTIPPP Contracts. Public Policy Adm. 2003, 18, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.C.; Wang, D.; Lee, P.T.; Tsang, Y.T. Modelling Risk Allocation Decision in Construction Contracts. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chan, A.P.; Yeung, J.F. Developing a Fuzzy Risk Allocation Model for PPP Projects in China. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.J. Performance of Public–Private Partnerships and the Influence of Contractual Arrangements. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2018, 41, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yeung, J.F.; Chan, A.P.; Chan, D.W.; Wang, S.Q.; Ke, Y. Developing a Risk Assessment Model for PPP Projects in China—A Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation Approach. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimsey, D.; Lewis, M.K. Evaluating the Risks of Public Private Partnerships for Infrastructure Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2002, 20, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yang, S.; Liu, C. Mining Heritage Reuse Risks: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.; Loosemore, M. Risk Allocation in the Private Provision of Public Infrastructure. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, A.Y. The Risk-Averting Game of Transport Public-Private Partnership: Lessons from the Adventure of California’s State Route 91 Express Lanes. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2012, 36, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.T.; Kirytopoulos, K.; Chileshe, N.; Rameezdeen, R. Taxonomy of Risks in PPP Transportation Projects: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medda, F. A Game Theory Approach for the Allocation of Risks in Transport Public Private Partnerships. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iossa, E.; Martimort, D. Risk Allocation and the Costs and Benefits of Public-Private Partnerships. RAND J. Econ. 2012, 43, 442–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.H. Determinants of Efficient Risk Allocation in Privately Financed Public Infrastructure Projects in Australia. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalate, D.; Bel, G.; Bel-Piñana, P.; Geddes, R.R. Risk Mitigation and Sharing in Motorway PPPs: A Comparative Policy Analysis of Alternative Approaches. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2015, 17, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, L.; Akintoye, A.; Edwards, P.J.; Hardcastle, C. The Allocation of Risk in PPP/PFI Construction Projects in the UK. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2005, 23, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, S.; Chan, A.P.; Lam, P.T. Preferred Risk Allocation in China’s Public–Private Partnership (PPP) Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P. Risk Assessment in Public-Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects: Empirical Comparison between Ghana and Hong Kong. Constr. Innov. 2017, 17, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.G.; Zhao, X.; Gay, M.J.S. Public Private Partnership Projects in Singapore: Factors, Critical Risks and Preferred Risk Allocation from the Perspective of Contractors. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.Y.; Platten, A.; Deng, X.P. Role of Public Private Partnerships to Manage Risks in Public Sector Projects in Hong Kong. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, B.; Xiong, W.; Wu, G. Commercial Investment in Public–Private Partnerships: The Impact of Contract Characteristics. Policy Politics 2018, 46, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athias, L. Local Public-Services Provision Under Public–Private Partnerships: Contractual Design and Contracting Parties Incentives. Local Govt. Stud. 2013, 39, 312–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farneti, F.; Young, D.W. A Contingency Approach to Managing Outsourcing Risk in Municipalities. Public Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Tam, V.W.; Gan, L.; Ye, K.; Zhao, Z. Improving Sustainability Performance for Public-Private-Partnership (PPP) Projects. Sustainability 2016, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybnicek, R.; Plakolm, J.; Baumgartner, L. Risks in Public-Private Partnerships: A Systematic Literature Review of Risk Factors, Their Impact and Risk Mitigation Strategies. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2020, 43, 1174–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Q.; Kabir, M.H.; Chaudhri, V. Managing Infrastructure Projects in Australia: A Shift from a Contractual to a Collaborative Public Management Strategy. Adm. Soc. 2014, 46, 422–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L.; Potoski, M.; Van Slyke, D.M. Contracting for Complex Products. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2010, 20, i41–i58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, T.; Martin, S. From Competition to Collaboration in Public Service Delivery: A New Agenda for Research. Public Adm. 2005, 83, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, G.A. The Risky Business of Public–Private Partnerships. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2004, 63, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.; Klijn, E.H.; Verweij, S.; Duijn, M.; van Meerkerk, I.; Metselaar, S.; Warsen, R. The Performance of Public–Private Partnerships: An Evaluation of 15 Years DBFM in Dutch Infrastructure Governance. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2022, 45, 998–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teisman, G.R.; Klijn, E.H. Partnership Arrangements: Governmental Rhetoric or Governance Scheme? Public Adm. Rev. 2002, 62, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, D.; Shadrina, E. Public-Private Partnerships as Collaborative Projects: Testing the Theory on Cases from EU and Russia. Int. J. Public Adm. 2018, 41, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Jia, G.; Hu, Y.; Xiong, W. Mediating Effect of Joint Action on Governing Complex Public Contracting. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2022, 45, 1066–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.H.; Teisman, G.R. Institutional and Strategic Barriers to Public—Private Partnership: An Analysis of Dutch Cases. Public Money Manag. 2003, 23, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casady, C.B. Examining the Institutional Drivers of Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Market Performance: A Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 981–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casady, C.B.; Eriksson, K.; Levitt, R.E.; Scott, W.R. (Re) Defining Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in the New Public Governance (NPG) Paradigm: An Institutional Maturity Perspective. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooste, S.F.; Scott, W.R. The Public–Private Partnership Enabling Field: Evidence from Three Cases. Adm. Soc. 2012, 44, 149–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Hurk, M.; Brogaard, L.; Lember, V.; Helby Petersen, O.; Witz, P. National Varieties of Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs): A Comparative Analysis of PPP-Supporting Units in 19 European Countries. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2016, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L.; Potoski, M. Managing the Public Service Market. Public Adm. Rev. 2004, 64, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.B. Transaction Costs in Public–Private Partnerships: The Weight of Institutional Quality in Developing Countries Revisited. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2016, 40, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, N.; Shahzad, W.; Khalfan, M.; Rotimi, J.O.B. Risk Identification, Assessment, and Allocation in PPP Projects: A Systematic Review. Buildings 2022, 12, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Chen, B.; Wang, H.; Zhu, D. Transaction Hazards and Governance Mechanisms in Public-Private Partnerships: A Comparative Study of Two Cases. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2019, 42, 1279–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, J.; Fraser, I.; McGarvey, N. Transparency of Risk and Reward in UK Public–Private Partnerships. Public Budg. Financ. 2006, 26, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.; Taeihagh, A. Smart City Governance in Developing Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsen, R.; Nederhand, J.; Klijn, E.H.; Grotenbreg, S.; Koppenjan, J. What Makes Public-Private Partnerships Work? Survey Research into the Outcomes and the Quality of Cooperation in PPPs. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 1165–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hubbard, M. Power Relations and Risk Allocation in the Governance of Public Private Partnerships: A Case Study from China. Policy Soc. 2012, 31, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C. Post-Contractual Lock-In and the UK Private Finance Initiative (PFI): The Cases of National Savings and Investments and the Lord Chancellor’s Department. Public Adm. 2005, 83, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.M.; Andrews, R. Can Public–Private Innovation Partnerships Improve Public Services? Evidence from a Synthetic Control Approach. Public Adm. Rev. 2022, 82, 1138–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunjes, B.M. Your Competitive Side Is Calling: An Analysis of Florida Contract Performance. Public Adm. Rev. 2022, 82, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Chang-Richards, Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Li, T.C. Effects of Project Governance Structures on the Management of Risks in Major Infrastructure Projects: A Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefetz, A.; Warner, M.; Vigoda-Gadot, E. Concurrent Sourcing in the Public Sector: A Strategy to Manage Contracting Risk. Int. Public Manag. J. 2014, 17, 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsilio, M.; Cappellaro, G.; Cuccurullo, C. The Intellectual Structure of Research into PPPS: A Bibliometric Analysis. Public Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, D.; Srivastava, A.K. Managing Partner Opportunism in Public–Private Partnerships: The Dynamics of Governance Adaptation. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 1420–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiong, W.; Wu, G.; Zhu, D. Public–Private Partnership in Public Administration Discipline: A Literature Review. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.H.; Koppenjan, J. The Impact of Contract Characteristics on the Performance of Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs). Public Money Manag. 2016, 36, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L.; Potoski, M. Managing Contract Performance: A Transaction Costs Approach. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2003, 22, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Slyke, D.M. The Mythology of Privatization in Contracting for Social Services. Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskin, E.; Tirole, J. Public–Private Partnerships and Government Spending Limits. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2008, 26, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynaers, A.M.; Grimmelikhuijsen, S. Transparency in Public–Private Partnerships: Not So Bad After All? Public Adm. 2015, 93, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaba Stadler, F.; Roehrich, J.; Conway, S.; Turner, J. Overcoming Information Asymmetry in Public-Private Relationships: Boundary Objects in Contracts. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2022, 1, 12278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L.; Potoski, M. Contract–Management Capacity in Municipal and County Governments. Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernita Joaquin, M.; Greitens, T.J. Contract Management Capacity Breakdown? An Analysis of US Local Governments. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Savas, E.S. Managing Collaborative Service Delivery: Comparing China and the United States. Public Adm. Rev. 2009, 69, S101–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, J.L.; Bolaños, L.A.; Daito, N.; Casady, C.B. What Triggers Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Renegotiations in the United States? Public Manag. Rev. 2023, 26, 1583–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Hsieh, J.Y.; Li, T.S. Contracting Capacity and Perceived Contracting Performance: Nonlinear Effects and the Role of Time. Public Adm. Rev. 2009, 69, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Du, Q.; Wang, K. A Concession Period and Price Determination Model for PPP Projects: Based on Real Options and Risk Allocation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchi, V.; Cusumano, N. A Regulatory Disaster or a Lack of Skills? The ‘Non-Value for Money’ of Motorway Concessions in Italy Revealed After the Genoa Bridge Collapse. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 1147–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Del Barrio Álvarez, D.; Yuan, J.; Kato, H. Determinants of the Formation Process in Public-Private Partnership Projects in Developing Countries: Evidence from China. Local Gov. Stud. 2023, 50, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Zhong, N.; Wang, F.; Zhang, M.; Chen, B. Political Opportunism and Transaction Costs in Contractual Choice of Public–Private Partnerships. Public Adm. 2022, 100, 1125–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lange, D. Sustainable Transportation for the Climate: How Do Transportation Firms Engage in Cooperative Public-Private Partnerships? Sustainability 2023, 15, 8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.M.; Romzek, B.S. Contracting and Accountability in State Medicaid Reform: Rhetoric, Theories, and Reality. Public Adm. Rev. 1999, 59, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasavage, D. Private Investment and Political Institutions. Econ. Politics 2002, 14, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeRoux, K.; Carr, J.B. Explaining Local Government Cooperation on Public Works: Evidence from Michigan. Public Work. Manag. Policy 2007, 12, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, J. Exploring the Risk Factors of Infrastructure PPP Projects for Sustainable Delivery: A Social Network Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R.; Heafey, M.; King, D. The Private Finance Initiative in the UK: A Value for Money and Economic Analysis. Public Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samii, R.; Van Wassenhove, L.N.; Bhattacharya, S. An Innovative Public–Private Partnership: New Approach to Development. World Dev. 2002, 30, 991–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, H.C.; de Araújo, J. Public-Private Partnerships/Private Finance Initiatives in Portugal: Theory, Practice, and Results. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2012, 36, 316–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Hao, S.; Li, X. Project Sustainability and Public-Private Partnership: The Role of Government Relation Orientation and Project Governance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwatari, M.; Kawakami, H.; Sasaki, D.; Sakamoto, A.; Nakayama, M. Enhancing Disaster Resilience for Sustainable Urban Development: Public–Private Partnerships in Japan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D.; Leonardi, R.; Nanetti, R.Y. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleta-Asín, J.; Muñoz-Sánchez, F.; Gimeno-Feliú, J.M. Does the Past Matter? Unravelling the Temporal Interdependencies of Institutions in the Success of Public–Private Partnerships. Public Manag. Rev. 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estache, A.; González, M.; Trujillo, L. Efficiency Gains from Port Reform and the Potential for Yardstick Competition: Lessons from Mexico. World Dev. 2002, 30, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quelin, B.V.; Cabral, S.; Lazzarini, S.; Kivleniece, I. The Private Scope in Public–Private Collaborations: An Institutional and Capability-Based Perspective. Organ. Sci. 2019, 30, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, X.; Shi, Y. Commercial Investment in Public–Private Partnerships: The Impact of Government Characteristics. Local Gov. Stud. 2023, 50, 230–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zhao, J.Z. The Rise of Public–Private Partnerships in China: An Effective Financing Approach for Infrastructure Investment? Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Ke, Y.; Wang, S. Case-Based Analysis of the Main Risk Factors of PPP Projects in China. Chin. Soft Sci. 2009, 5, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, A.; Hellowell, M. A Comparative Analysis and Evaluation of Specialist PPP Units’ Methodologies for Conducting Value for Money Appraisals. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2017, 19, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S. Value for Money?: Causative Lessons about P3s from British Columbia; Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives-BC Office: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hofmann, D.A. An Overview of the Logic and Rational of Hierarchical Linear Models. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 723–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.A.; Gavin, M.B. Centering Decisions in Hierarchical Linear Models: Implications for Research in Organizations. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C.K.; Tofighi, D. Centering Predictor Variables in Cross-Sectional Multilevel Models: A New Look at an Old Issue. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiue, J.E.; Taylor, S.R. A Framework for Testing Meso-Mediational Relationships in Organizational Behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S.; Cheong, Y.F.; Congdon, R.T., Jr. HLM 6: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling; Scientific Software International: Skokie, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hox, J.; Moerbeek, M.; Van de Schoot, R. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henisz, W.J.; Levitt, R.E.; Scott, W.R. Toward a Unified Theory of Project Governance: Economic, Sociological and Psychological Supports for Relational Contracting. Eng. Proj. Organ. J. 2012, 2, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, S.; Vanelslander, T. Comparison of Public–Private Partnerships in Airports and Seaports in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Transp. Rev. 2015, 35, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz Cesar, A.V. Public–Private Partnerships in Highways in Transition Economies: Recent Experience and Future Prospects. Transp. Res. Rec. 2007, 1996, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Karim, N.A. Risk Allocation in Public Private Partnership (PPP) Project: A Review on Risk Factors. Int. J. Sustain. Construct. Eng. Technol. 2011, 2, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Bel-Piñana, P.; Rosell, J. Myopic PPPs: Risk Allocation and Hidden Liabilities for Taxpayers and Users. Util. Policy 2017, 48, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Variable Name | Measurement | Data Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Risk Identification and Allocation | Specific values The larger the value, the better the degree of risk identification and allocation. | China Public Private Partnerships Center (CPPPC) | |

| Independent Variables | Program Level—Institutional Arrangements | Degree of Potential Competition | Specific values The larger the value, the better the degree of potential competition | China Public Private Partnerships Center (CPPPC) |

| Degree of Full Life-Cycle Integration | Specific values The larger the value, the better the degree of full life-cycle integration | China Public Private Partnerships Center (CPPPC) | ||

| Institutional Environment Level | Number of Registered Social Organizations | Specific values The larger the value, the better the degree of social capital | National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS) | |

| Government Care—Government Care Index (2018) | Specific values The larger the value, the better the government–enterprise relationship | China Government-Business Relations Report (2018) | ||

| Government Clean—Cleanliness Index (2018) | Specific values The lower the value, the higher the government’s cleanliness | China Government-Business Relations Report (2018) | ||

| Policy Transparency (2018) | Specific values The larger the value, the higher the policy transparency | Government Transparency Index Report | ||

| Judicial Impartiality (2018) | Specific values The larger the value, the higher the degree of judicial impartiality | China Judicial Civility Index Report | ||

| Control Variables | Procurement Methods | 1: Invitation to tender 2: Single-source procurement 3: Competitive negotiation 4: Competitive consultation 5: Open tendering | China Public Private Partnerships Center (CPPPC) | |

| Industry | 1: Infrastructure 2: Ecological conservation 3: Social and livelihood 4: Other | China Public Private Partnerships Center (CPPPC) | ||

| Modus Operandi | 1: BOT 2: TOT 3: ROT 4: OM 5: BOO 6: Other | China Public Private Partnerships Center (CPPPC) | ||

| Return Mechanism | 1: Feasibility gap grant 2: Government expense 3: User fees | China Public Private Partnerships Center (CPPPC) | ||

| PPP Stage | 1: The preparatory phase 2: The procurement phase 3: The implementation phase | China Public Private Partnerships Center (CPPPC) | ||

| Mean | Mean | SD | Data Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RISK | Risk identification and allocation | 80.625 | 6.684 | CPPPC a |

| Institutional Arrangements | ||||

| COMP | Degree of potential competition | 80.961 | 6.877 | CPPPC |

| INTE | Degree of full life-cycle integration | 82.761 | 6.299 | CPPPC |

| Institutional environment | ||||

| SOCP | Number of registered social organizations (logarithmically processed) | 10.135 | 0.600 | NBSC b |

| CARE | Government Care Index | 18.849 | 7.296 | CGBRR c (2018) |

| GOIN | Cleanliness Index | 10.284 | 6.303 | CGBRR d (2018) |

| TRAS | Policy Transparency Index | 70.359 | 7.470 | CGBRR e (2018) |

| JUIM | Judicial impartiality | 69.297 | 1.339 | CGTR f (2018) |

| Control variables | ||||

| PREI | Duration of cooperation | 21.340 | 6.633 | CPPPC |

| DCNS | Dummy variables for infrastructure | 0.635 | - | CPPPC |

| DECL | Dummy variables for the ecological conservation domain | 0.225 | - | CPPPC |

| DSEC | Dummy variables for social and livelihood domains | 0.127 | - | CPPPC |

| DITT | Dummy variables for invitation to tender | 0.002 | - | CPPPC |

| DSSP | Dummy variables for single-source procurement | 0.007 | - | CPPPC |

| DCNE | Dummy variables for competitive negotiation | 0.002 | - | CPPPC |

| DCCN | Dummy variables for competitive consultation | 0.069 | - | CPPPC |

| DBOT | Dummy variable for BOT | 0.776 | - | CPPPC |

| DTOT | Dummy variable for TOT | 0.064 | - | CPPPC |

| DROT | Dummy variable for ROT | 0.065 | - | CPPPC |

| DOOM | Dummy variable for OM | 0.002 | - | CPPPC |

| DBOO | Dummy variable for BOO | 0.005 | - | CPPPC |

| DQBZ | Dummy variables for feasibility gap grant | 0.738 | - | CPPPC |

| DZFF | Dummy variables for government expense | 0.226 | - | CPPPC |

| DPRE | Dummy variables for preparatory phase | 0.076 | - | CPPPC |

| DPRC | Dummy variables for procurement phase | 0.411 | - | CPPPC |

| D018 | Dummy variables for the year 2018 | 0.195 | - | CPPPC |

| D019 | Dummy variables for the year 2019 | 0.208 | - | CPPPC |

| D020 | Dummy variables for the year 2020 | 0.263 | - | CPPPC |

| D021 | Dummy variables for the year 2021 | 0.044 | - | CPPPC |

| 1 a | 2 b | 3 b | 4 b | 5 b | 6 b | 7 a | 8 a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. RISK a | - | |||||||

| 2. SOCP b | 0.136 ** | - | ||||||

| 3. CARE b | 0.141 ** | 0.062 | - | |||||

| 4. GOIN b | 0.039 * | −0.099 | −0.299 | - | ||||

| 5. TRAS b | 0.050 ** | 0.152 | 0.443 * | −0.473 ** | - | |||

| 6. JUIM b | 0.024 | 0.151 | 0.441 * | −0.231 | 0.358 * | - | ||

| 7. COMP a | 0.664 ** | 0.109 ** | 0.136 ** | 0.050 ** | 0.063 ** | 0.010 | - | |

| 8. INTE a | 0.742 ** | 0.102 ** | 0.134 ** | 0.026 | 0.071 ** | −0.016 | 0.612 ** | - |

| 9. PERI a | −0.039 * | −0.043 * | 0.066 ** | −0.049 ** | −0.037 * | −0.148 ** | 0.008 | 0.035 |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effect a | |||||

| ) | |||||

| ) | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Random effect b | |||||

| Variance Component | |||||

| 37.156 | 14.946 | 37.154 | 14.943 | 14.921 | |

| Deviance | 18,961.086 | 16,404.006 | 18,975.430 | 16,414.925 | 16,492.292 |

| Number of estimated parameters | 2 | 11 | 2 | 11 | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Hu, L.; Li, Y. Institutional Environment, Institutional Arrangements, and Risk Identification and Allocation in Public–Private Partnerships: A Multilevel Model Analysis Based on Data from 31 Provinces in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156674

Yang L, Hu L, Li Y. Institutional Environment, Institutional Arrangements, and Risk Identification and Allocation in Public–Private Partnerships: A Multilevel Model Analysis Based on Data from 31 Provinces in China. Sustainability. 2024; 16(15):6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156674

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Lei, Longji Hu, and Yifan Li. 2024. "Institutional Environment, Institutional Arrangements, and Risk Identification and Allocation in Public–Private Partnerships: A Multilevel Model Analysis Based on Data from 31 Provinces in China" Sustainability 16, no. 15: 6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156674

APA StyleYang, L., Hu, L., & Li, Y. (2024). Institutional Environment, Institutional Arrangements, and Risk Identification and Allocation in Public–Private Partnerships: A Multilevel Model Analysis Based on Data from 31 Provinces in China. Sustainability, 16(15), 6674. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156674