Sustainable Human Resource Management and Employees’ Performance: The Impact of National Culture

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Sustainable Human Resource Management Practices and Performance

2.2. The Mediating Role of Employees’ Engagement

2.3. The Moderating Role of National Culture

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Individual-Level Measures (Questionnaire)

Sustainable Human Resource Management (SHRM)

Employees’ Engagement

Perceived Performance

3.2.2. National-Level Variable

Tightness–Looseness Scores

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Analytic Strategy

3.4. Preliminary Tests for Data Quality

4. Results

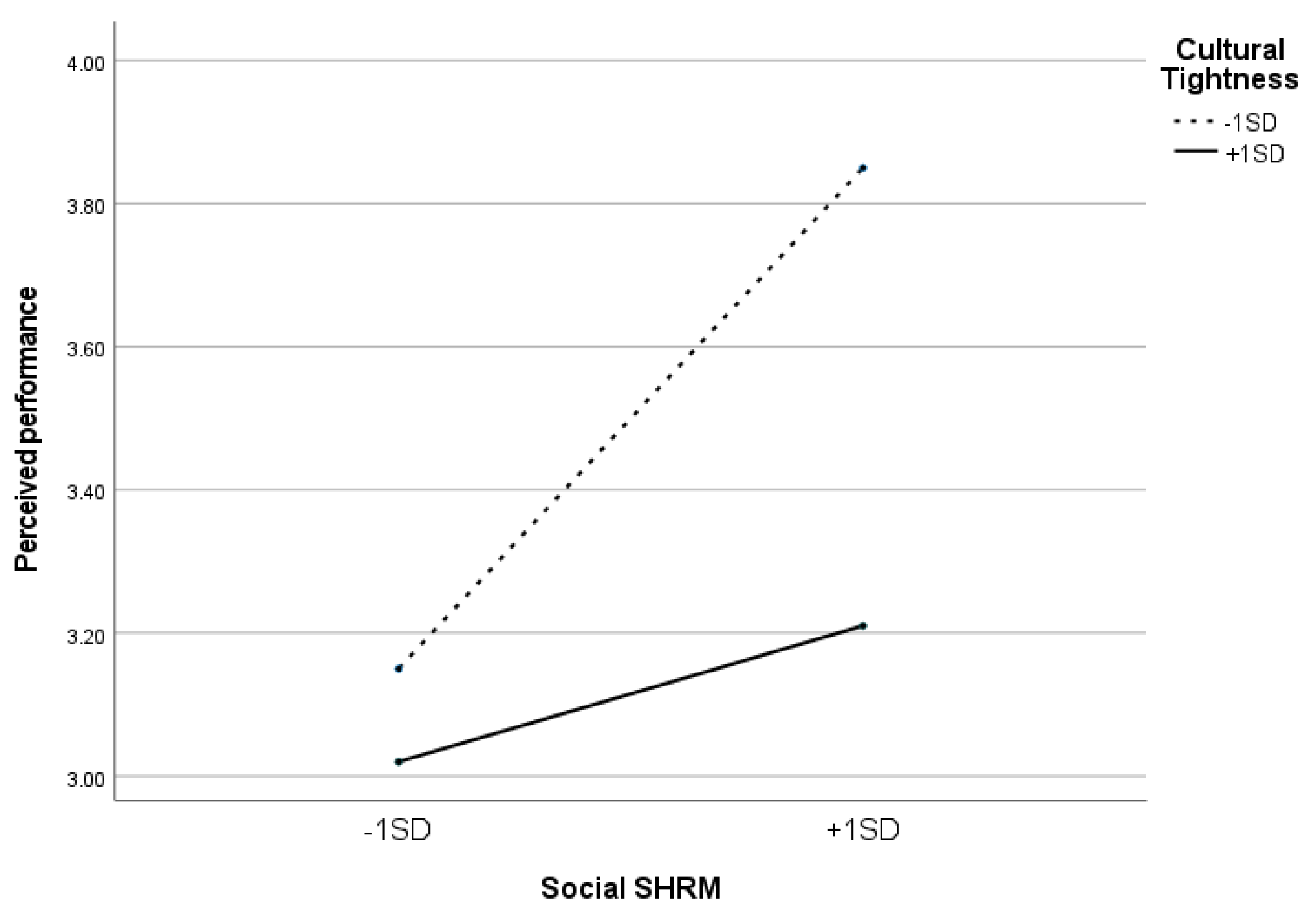

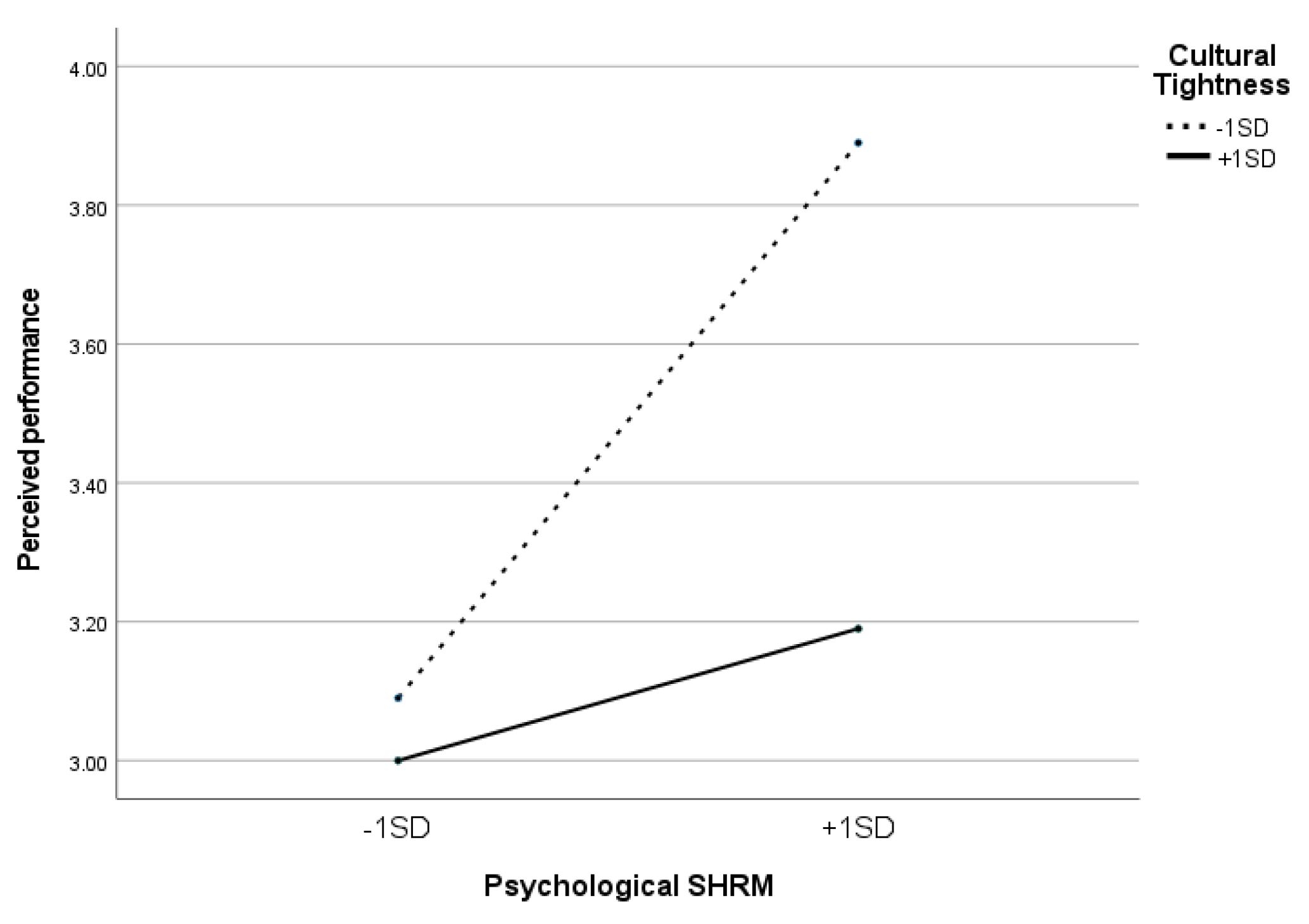

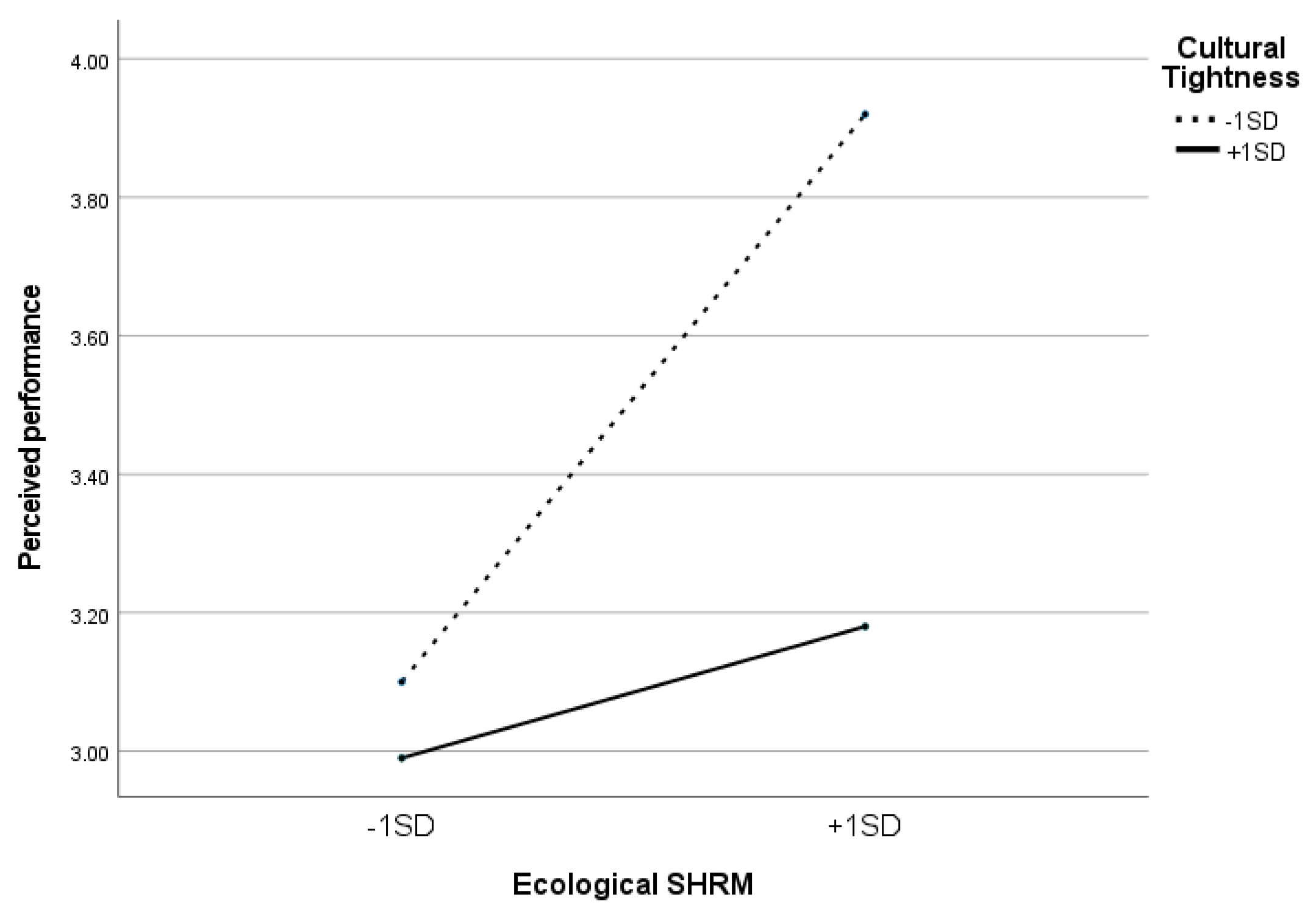

Tests of Hypothesis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karman, A. Understanding sustainable human resource management–organizational value linkages: The strength of the SHRM system. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2020, 39, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Luthra, S.; Joshi, S.; Kumar, A. Analysing the impact of sustainable human resource management practices and industry 4.0 technologies adoption on employability skills. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortia, E.C.; Sacchetti, S.; López-Arceiz, F.J. A human growth perspective on sustainable HRM practices, worker well-being, and organizational performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, J.W.; Rao, M.B.; Vanka, S.; Gupta, M. Sustainable human resource management and the triple bottom line: Multi-stakeholder strategies, concepts, and engagement. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zaman, S.I.; Jamil, S.; Khan, S.A.; Kun, L. A triple theory approach to link corporate social performance and green human resource management. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 15733–15776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, B.; Walczyna, A. Bridging sustainable human resource management and corporate sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, N.Y.; Farrukh, M.; Raza, A. Green human resource management and employees pro-environmental behaviors: Examining the underlying mechanism. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnalatha, D.C.; Prasanna, T.S. Employee engagement: The key to organizational success. Int. J. Manag. (IJM) 2012, 3, 216–227. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, R.; EJackson, S. Human resource management and organizational effectiveness: Yesterday and today. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2014, 1, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boselie, P.; van der Heijden, B. Strategic Human Resource Management: A Balanced Approach; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, J.; Morgan, D. An empirical study of ‘green’workplace behaviours: Ability, motivation and opportunity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 56, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, D.; Ferris, G.R. Critical factors in human resource practice implementation: Implications of cross-cultural contextual issues. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2011, 11, 112–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aycan, Z. The interplay between cultural and institutional/structural contingencies in human resource management practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 16, 1083–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretz, H.; Knappert, L. The cultural lens. In The Oxford Handbook on Contextual Approaches to Human Resource Management; Parry, E., Brewster, C., Morley, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 24–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1984; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tarique, I.; Briscoe, D.R.; Schuler, R.S. International Human Resource Management: Policies and Practices for Multinational Enterprises; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. (Eds.) The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamubarwa, W.; Chipunza, C. Debunking the one-size-fits-all approach to human resource management: A review of human resource practices in small and medium-sized enterprise firms. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.; Lopez-Cabrales, A. Sustainable development and human resource management: A science mapping approach. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1171–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, T.S.C.; Law, K.K. Sustainable HRM: An extension of the paradox perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2022, 32, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Savanevičienė, A. Designing sustainable HRM: The core characteristics of emerging field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Karatepe, O.M. Green human resource management, perceived green organizational support and their effects on hotel employees’ behavioral outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3199–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G.K.; Brewster, C.J.; Collings, D.G.; Hajro, A. Enhancing the role of human resource management in corporate sustainability and social responsibility: A multi-stakeholder, multidimensional approach to HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S. Twenty-year journey of sustainable human resource management research: A bibliometric analysis. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKetbi, A.; Rice, J. The Impact of Green Human Resource Management Practices on Employees, Clients, and Organizational Performance: A Literature Review. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järlström, M.; Saru, E.; Vanhala, S. Sustainable human resource management with salience of stakeholders: A top management perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, L.; Cheung, Y.H.; Herndon, N.C. For all good reasons: Role of values in organizational sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I.; Parsa, S.; Roper, I.; Wagner, M.; Muller-Camen, M. Reporting on sustainability and HRM: A comparative study of sustainability reporting practices by the world’s largest companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Carrion, R.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernandez, P.M. Developing a sustainable HRM system from a contextual perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. A conceptual framework for cost measures of harm of HRM practices. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2013, 5, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, A.Z.; Shigutu, A.D.; Tensay, A.T. The effect of employees’ perception of performance appraisal on their work outcomes. Int. J. Manag. Commer. Innov. 2014, 2, 136–173. [Google Scholar]

- Vänni, K.; Virtanen, P.; Luukkaala, T.; Nygård, C.H. Relationship between perceived work ability and productivity loss. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2012, 18, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, C.; Rizzi, F.; Frey, M. The role of sustainable human resource practices in influencing employee behavior for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Becker, T.E.; Vandenberghe, C. Employee commitment and motivation: A conceptual analysis and integrative model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon-Fowler, H.; O’Leary-Kelly, A.; Johnson, J.; Waite, M. Sustainability and ideology-infused psychological contracts: An organizational-and employee-level perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugueró-Escofet, N.; Ficapal-Cusí, P.; Torrent-Sellens, J. Sustainable human resource management: How to create a knowledge-sharing behavior through organizational justice, organizational support, satisfaction, and commitment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; Den Hartog, D.N.; Boselie, P.; Paauwe, J. The relationship between perceptions of HR practices and employee outcomes: Examining the role of person-organization and person-job fit. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 138–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, O.; Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z. Effect of CSR participation on employee sense of purpose and experienced meaningfulness: A self-determination theory perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R.; Buzzanell, P.M. Communicative tensions of meaningful work: The case of sustainability practitioners. Hum. Relat. 2017, 70, 594–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Enabling employees to employ more of their whole selves at work. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 183377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzopoulou, E.C.; Manolopoulos, D.; Agapitou, V. Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: Interrelations of external and internal orientations with job satisfaction and organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 179, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Kwon, H. The impact of employees’ perceptions of strategic alignment on sustainability: An empirical investigation of Korean firms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroufe, R. Integration and organizational change towards sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Han, S.J.; Park, J. Is the role of work engagement essential to employee performance or ‘nice to have’? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopiah, S.; Kurniawan, D.T.; Elfia, N.O.R.A.; Narmaditya, B.S. Does talent management affect employee performance?: The moderating role of work engagement. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldabbas, H.; Pinnington, A.; Lahrech, A. The influence of perceived organizational support on employee creativity: The mediating role of work engagement. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 6501–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F. The relationship between perceived organizational support and work engagement: The role of self-efficacy and its outcomes. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 64, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ajlouni, M.I. Can high-performance work systems (HPWS) promote organizational innovation? Employee perspective-taking, engagement, and creativity in a moderated mediation model. Employee Relations. Int. J. 2021, 43, 373–397. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, A.M. Caring for human resources management and employee engagement. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2022, 32, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, S.; Duarte, A.P.; Simões, E. How socially responsible human resource management fosters work engagement: The role of perceived organizational support and affective organizational commitment. Soc. Responsib. J. 2024, 20, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuti, A.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Molino, M.; Ingusci, E.; Russo, V.; Signore, F.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. “Everything will be fine”: A study on the relationship between employees’ perception of sustainable HRM practices and positive organizational behavior during COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markos, S.; Sridevi, M.S. Employee engagement: The key to improving performance. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Cesário, F.; Chambel, M.J. Linking organizational commitment and work engagement to employee performance. Knowl. Process Manag. 2017, 24, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauchli, R.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Jenny, G.J.; Füllemann, D.; Bauer, G.F. Disentangling stability and change in job resources, job demands, and employee well-being—A three-wave study on the Job-Demands Resources model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hakanen, J.J.; Demerouti, E.; Xanthopoulou, D. Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, D.R.; Chiu, C.Y.; Schaller, M. Psychology and culture. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 689–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanel, P.H.; Maio, G.R.; Soares, A.K.; Vione, K.C.; de Holanda Coelho, G.L.; Gouveia, V.V.; Manstead, A.S. Cross-cultural differences and similarities in human value instantiation. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 366179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.F. Cross-Cultural Similarities and Differences; Oxford Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber, A.L.; Kluckhohn, C. Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions; Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; McCrae, R.R. Personality and culture revisited: Linking traits and dimensions of culture. Cross-Cult. Res. 2004, 38, 52–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; McIver, R. Does national culture affect attitudes toward environment-friendly practices? In Handbook of Environmental and Sustainable Finance; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 241–263. [Google Scholar]

- Halder, P.; Hansen, E.N.; Kangas, J.; Laukkanen, T. How national culture and ethics matter in consumers’ green consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle, E.; Mensah, M.E. The influence of national culture on expatriate work adjustment, intention to leave and organizational commitment. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, M.; Toffel, M.W. Stakeholders and environmental management practices: An institutional framework. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2004, 13, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, J.C.; Garcia, M.A.; Putnam, L.L.; Mumby, D.K. Institutional theory. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Communication: Advances in Theory, Research, and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K.; Lengnick-Hall, M.L. MNC practice transfer: Institutional theory, strategic opportunities, and subsidiary HR configuration. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 3813–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.C.; Cardy, R.L.; Huang, L.S. Institutional theory and HRM: A new look. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 316–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Nishii, L.H.; Raver, J.L. On the nature and importance of cultural tightness-looseness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, J.R.; Gelfand, M.J. Tightness–looseness across the 50 United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7990–7995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Gordon, S.; Gelfand, M.J. Tightness–looseness: A new framework to understand consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uz, I. The index of cultural tightness and looseness among 68 countries. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2015, 46, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knappert, L.; Peretz, H.; Aycan, Z.; Budhwar, P. Staffing effectiveness across countries: An institutional perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2023, 33, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeffane, R.; Al Zarooni, H.A.M. The influence of empowerment, commitment, job satisfaction and trust on perceived managers’ performance. Int. J. Bus. Excell. 2008, 1, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, T.A.; Khattak, M.N.; Zolin, R.; Shah, S.Z.A. Psychological empowerment and employee attitudinal outcomes: The pivotal role of psychological capital. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa Pacheco, P.; Coello-Montecel, D.; Tello, M. Psychological empowerment and job performance: Examining serial mediation effects of self-efficacy and affective commitment. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, R.Y.; Roth, Y.; Lemoine, J.F. The impact of culture on creativity: How cultural tightness and cultural distance affect global innovation crowdsourcing work. Adm. Sci. Q. 2015, 60, 189–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, J.; Aksoy, E.; Tesfa Alemu, G. Perceptions of organizational tightness–looseness moderate associations between perceived unfair discrimination and employees’ job attitudes. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2022, 53, 426–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, C.M.; Shore, L.M. Demographic diversity and employee attitudes: An empirical examination of relational demography within work units. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M.J. Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science 2011, 332, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K.; Strimling, P.; Gelfand, M.; Wu, J.; Abernathy, J.; Akotia, C.S.; Van Lange, P.A. Perceptions of the appropriate response to norm violation in 57 societies. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakrošienė, A.; Bučiūnienė, I.; Goštautaitė, B. Working from home: Characteristics and outcomes of telework. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 40, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L. Mplus. In Handbook of Item Response Theory; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders, T.A.B.; Bosker, R.J. Discrete dependent variables. In Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; pp. 304–307. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, M.W.L.; Leung, K.; Au, K. Evaluating multilevel models in cross-cultural research: An illustration with social axioms. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2006, 37, 522–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarova, M.; Peretz, H.; Fried, Y. Locals know best? Subsidiary HR autonomy and subsidiary performance. J. World Bus. 2017, 52, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Lance, C.E. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organ. Res. Methods 2000, 3, 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D.J.; Preacher, K.J.; Gil, K.M. Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2006, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job demands-resources theory: Ten years later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, F.; Guest, D.; Ramos, J.; Gracia, F.J. High commitment HR practices, the employment relationship and job performance: A test of a mediation model. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzafrir, S.S. The relationship between trust, HRM practices, and firm performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 16, 1600–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green human resource management: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W.; Higgins, C.; Milne, M. Why do companies not produce sustainability reports? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Van Ruysseveldt, J.; Vanbelle, E.; De Witte, H. The job demands-resources model: Overview and suggestions for future research. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; pp. 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas and Interests; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W.; Greenwood, R.; Oliver, C. Reflections on institutional theories of organizations. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 831–852. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, C.J.; Santos, F.C. The central role of human resource management in the search for sustainable organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L. Fundamentals of human resource management for environmentally sustainable supply chains. In Handbook on the Sustainable Supply Chain; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Cooke, F.L.; Stahl, G.K.; Fan, D.; Timming, A.R. Advancing the sustainability agenda through strategic human resource management: Insights and suggestions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 62, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Score | Tightness Level |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 1.56 | Low |

| Australia | 1.9 | Medium |

| Austria | 2.1 | High |

| Brazil | 1.69 | Low |

| Canada | 1.83 | Medium |

| Chile | 1.68 | Low |

| Estonia | 1.62 | Low |

| Finland | 1.75 | Medium |

| Germany | 2.03 | High |

| Greece | 1.71 | Medium |

| Hungary | 1.46 | Low |

| Iceland | 1.94 | High |

| India | 2.48 | High |

| Ireland | 1.8 | Medium |

| Israel | 1.66 | Low |

| Italy | 1.87 | Medium |

| Japan | 2.09 | High |

| Korea | 2.09 | High |

| Mexico | 1.69 | Low |

| The Netherlands | 1.59 | Low |

| Poland | 1.7 | Medium |

| Portugal | 2 | High |

| Spain | 1.71 | Medium |

| Sweden | 2.2 | High |

| UK | 1.77 | Medium |

| USA | 1.82 | Medium |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social SHRM | 3.42 | 0.73 | ||||

| 2. Psychological SHRM | 3.37 | 0.70 | 0.45 ** | |||

| 3. Ecological SHRM | 3.24 | 0.69 | 0.41 ** | 0.39 ** | ||

| 4. Employees’ perceived performance | 3.76 | 0.71 | 0.32 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.42 ** | |

| 5. Cultural tightness | 1.65 | 0.65 | −0.30 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.15 ** |

| Employees’ Perceived Performance | |

|---|---|

| Level 1 Main Effects | |

| Age | 0.14 * (0.04) |

| 1 Gender | 0.04 (0.02) |

| 2 Educational level | 0.24 ** (0.11) |

| Social SHRM | 0.28 ** (0.15) |

| Psychological SHRM | 0.23 ** (0.10) |

| Ecological SHRM | 0.36 ** (0.15) |

| ~R2 | 0.15 |

| Employees’ Perceived Performance | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | 1 Model 1 | 2 Model 2 |

| Level 1 Main Effects | ||

| Age | 0.14 * (0.04) | 0.12 * (0.04) |

| Gender | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.01) |

| Educational level | 0.24 ** (0.11) | 0.20 ** (0.09) |

| Social SHRM | 0.28 ** (0.15) | 0.19 ** (0.08) |

| Psychological SHRM | 0.23 ** (0.10) | 0.15 ** (0.06) |

| Ecological SHRM | 0.36 ** (0.15) | 0.21 ** (0.10) |

| Employees’ engagement | 0.32 ** (0.12) | 0.24 ** (0.11) |

| Level 1 Indirect Effects | ||

| Social SHRM via employees’ engagement | 0.21 ** (0.09) | |

| Psychological SHRM via employees’ engagement | 0.19 ** (0.08) | |

| Ecological SHRM via employees’ engagement | 0.25 ** (0.12) | |

| ~R2 | 0.18 | 0.28 |

| Δ~R2 | 0.10 | |

| Employees’ Perceived Performance | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | 1 Model 1 | 2 Model 2 |

| Level 1 Main Effects | ||

| Age | 0.13 * (0.04) | 0.13 * (0.04) |

| Gender | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.02) |

| Educational level | 0.22 ** (0.11) | 0.22 ** (0.11) |

| Social SHRM | 0.26 ** (0.14) | 0.24 ** (0.12) |

| Psychological SHRM | 0.21 ** (0.10) | 0.18 ** (0.09) |

| Ecological SHRM | 0.33 ** (0.14) | 0.27 ** (0.12) |

| Level 2 Main Effects | ||

| Cultural tightness level (TL) | −0.18 ** (0.07) | −0.15 ** (0.06) |

| Cross–Level Interactions | ||

| Social SHRM × TL | −0.20 ** (0.07) | |

| Psychological SHRM × TL | −21 ** (0.08) | |

| Ecological SHRM × TL | −24 ** (0.08) | |

| ~R2 | 0.17 | 0.25 |

| Δ~R2 | 0.08 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peretz, H. Sustainable Human Resource Management and Employees’ Performance: The Impact of National Culture. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177281

Peretz H. Sustainable Human Resource Management and Employees’ Performance: The Impact of National Culture. Sustainability. 2024; 16(17):7281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177281

Chicago/Turabian StylePeretz, Hilla. 2024. "Sustainable Human Resource Management and Employees’ Performance: The Impact of National Culture" Sustainability 16, no. 17: 7281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177281

APA StylePeretz, H. (2024). Sustainable Human Resource Management and Employees’ Performance: The Impact of National Culture. Sustainability, 16(17), 7281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177281