Abstract

Increasing environmental challenges are prompting sport managers to act to minimize negative ecological impacts. Educational opportunities for sport management students are critical for developing awareness and understanding of environmental sustainability across the sport industry. In 2012, Casper and Pfahl examined the personal environmental actions of sport administration and recreation students. The purpose of our current research is to expand on Casper and Pfahl’s work by assessing the predictive relationships of values, beliefs, and norms on behaviors related to environmental sustainability using the Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) framework. Sport management students (N = 510) representing 23 higher education institutions completed the online survey. Structural equation modeling showed minimal changes over ten years. Norms were the strongest predictors of pro-environmental behaviors, and results indicated that students hold sport management organizations to a higher environmental standard than traditional businesses. The authors provide discussion and recommendations on bridging the gap between academia and industry to better prepare students for their professional futures in the sport industry.

1. Introduction

The relationship between sport and the natural environment is codependently bi-directional [1,2]. The natural environment can impact the sport business; conversely, sport can harm the natural environment. For instance, unsafe environmental conditions, such as wildfires, have caused athletes to experience respiratory issues from inhaling smoke [3]. When it comes to golf, the maintenance of golf courses involves excessive use of chemicals, which can cause contamination of the underground water table, negatively alter and affect the local flora and fauna, and consequently reduce vegetation diversity [4]. Sport facility managers are also confronted with issues related to climate change. Dingle and colleagues [5] explored organizational responses to managing water resources, suggesting that managers should adopt strategies to harvest, store, and recycle water. Increasing challenges such as these are prompting sport managers to act, find solutions to minimize negative impacts on the environment, and use sport to bring awareness to spectators and participants.

Evidence shows that organizations within the sport industry continually increase the number of environmental initiatives in their operations [6]. This necessitates qualified and knowledgeable personnel to manage current and future challenges [7,8,9]. Along the same lines, Chalip [10] pointed out the importance of sport managers being equipped with the necessary skills to effectively address future issues that could emerge within the field of sport and sustainability. To set this direction, Mallen and Chard [11] offered a future path for environmental sustainability in sport, emphasizing the necessity of environmental education through discussions among scholars, students, and practitioners. The growth of such educational opportunities is critical for developing awareness and understanding of environmental sustainability across the sport industry [12].

In 2012, Casper and Pfahl examined the environmental awareness and personal environmental actions of undergraduate sport administration and recreation students, illustrating a relationship between students’ environmental values and level of environmental responsibility. Their work was the first to focus on sports management students’ values, beliefs, and norms (VBNs), providing an understanding of students’ environmental attitudes. Still, substantial changes in cultural attitudes and generational differences toward the environment have occurred over the past ten years. For example, there has been tremendous growth in the industry’s efforts to advance environmental sustainability into the daily operations of sport organizations (e.g., Forest Green Rovers, Philadelphia Eagles, World Athletics), including governance support from the International Olympic Committee and United Nations through the creation of the Sports for Climate Action Framework, Race to Zero, and Sports for Nature frameworks. Through this progression in the industry, the amount of literature focused on sport and the natural environment [13] has dramatically increased. Given the proliferation of industry efforts and available academic research, there is a need to re-evaluate sport management students’ awareness and knowledge of environmental sustainability. While the Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) theory is widely utilized, it is rarely applied to assess the ecological views of higher education students [14]. Instead, VBN has been more frequently employed to evaluate the perspectives of sports fans in academic settings (see McCullough), leaving a gap in understanding the ecological views of sport management students.

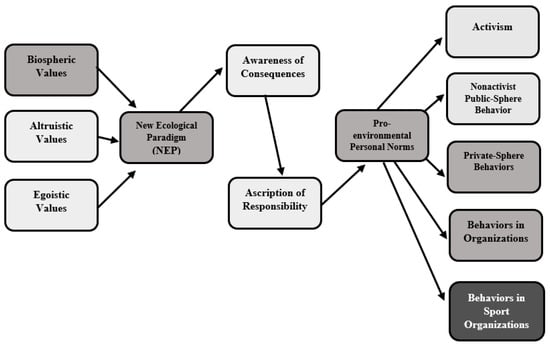

Therefore, this research aims to expand on Casper and Pfahl’s [15] work by reassessing and evaluating students’ awareness and the predictive relationships of values, beliefs, and norms on behaviors related to environmental sustainability. Newly designed survey items were also included in the instrument to address the curricula’s lack of environmental sustainability education. The new model shows an extension of the VBN theory used by Casper and Pfahl (Figure 1). It focuses explicitly on sport management students’ beliefs about sport organizations’ environmental sustainability behaviors. These data will provide faculty and educators with valuable information on the current environmental beliefs of sport management students to aid in designing, re-structuring, and implementing environmental sustainability modules and courses to serve the future generation of sport managers better. The paradox is that, although sport organizations are addressing sustainability and actively pursuing initiatives to minimize or mitigate the adverse effects on the environment, we as educators are lagging and not providing sufficient opportunities for students to learn and be trained to assist with these initiatives and programs. It is imperative to ensure that sport management students acquire the necessary knowledge to better serve an industry dedicated to addressing the intercept between sport and the natural environment.

Figure 1.

Extended VBN framework for the current study. Arrows show hypothetical direct consequences, though effects from a causal variable may be seen on other variables down the chain. The gray boxes are the constructs used in the 2012 and current study. The dark gray box is the new construct for this study.

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Environmental Sustainability in Higher Education

Today’s society faces a series of interrelated social, economic, and environmental crises. There is a pressing need to shift to a sustainable community that lives within the planet’s ecological bounds, recognizing the symbiotic relationship between nature and societal well-being [16,17]. However, such a shift requires a shift in our institutions [18], especially higher education. The importance of universities as future transformative agents for creating a sustainable society has been acknowledged and envisioned [19]. The role of universities in sustainability performance was especially emphasized during the decade-long United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Education for Sustainable Development (2005–2014) programme [20]. Sustainability became an emerging determinant, even for university rankings (e.g., UO green metric).

As higher education institutions, universities significantly impact society and can play a crucial role in sustainability provision. Higher education institutions have been identified as leaders in developing policies and solutions to advance the transition to a sustainable society [21]. As such, they are committed to preparing future professionals to be responsible citizens and create a more sustainable future [22]. Students play a critical role in advancing sustainability practices. Therefore, it is essential to provide opportunities for students to learn about environmental issues and solutions in the specific professional context in which they plan to pursue their careers post-graduation. The challenge is when educators adopt a somewhat reductive and non-substantive pedagogy, making it difficult to teach the topic effectively [23].

To address these challenges, universities worldwide increasingly engage in multi-stakeholder collaborations to co-create knowledge, tools, and experiments with social and technical systems for advancing societal sustainability. With many of these initiatives conceived primarily as faculty research projects, implications of knowledge co-creation for student sustainability learning and education are mainly under-examined [24]. This necessitates broader research interest to anticipate if and how students will take sustainable action by understanding their viewpoints on environmental sustainability. Moreover, considering the limited scholarship on curriculum development in higher education, especially for courses focused on environmental sustainability [25], it is imperative to address this gap. Students can be empowered to alter their attitudes and behaviors via education, enabling them to make more informed decisions [20]. This relationship is demonstrated by exploring students’ beliefs and attitudes about the environment and their desire to learn more about the impact of human actions on nature in general and specific professional settings. This, in turn, would not only provide them with the necessary knowledge to proactively address and solve related problems but also help them to succeed in their professional careers.

2.2. Environmental Sustainability in Sport Management Programs

Like other business industries, the sport sector is not an exception and is impacted by climate change [1]. Thus, there have been consistent and growing calls for sport management students to be prepared to address these challenges [12,26,27,28]. Despite these calls, there is a lack of dedicated classes or modules within sport management curricula focused on environmental issues [29,30]. Other scholars have examined the program descriptions, learning outcomes, and curricula of 84 sport management graduate programs across the United States and discovered that “the discipline [sport management] has coalesced around a key set of skills and content areas. This standardization may come at the expense of adaptability and responsiveness to changes in sport and society” [30], p. 1. To address this challenge, Mercado and Grady [27] suggested that students can learn sustainable concepts and see development in varying facets of sport management sectors through practical applications offered in different courses. Dingle and Mallen [28] further argued that a standalone course should be created first as a launching point, and then environmental sustainability should be added to each course in the curriculum. Of course, this comes with potential challenges, such as identifying partners or venues for practical experience and buy-in from the department, faculty, and students [27,28]. Others have noted that obstacles to creating and implementing environmental sustainability courses include the regional ecological beliefs of students, it not being deemed necessary by students, lack of available faculty and class space, it being too new of a topic, and lack of resources [29] Nevertheless, more education is needed to ensure that future sport management professionals have the knowledge and expertise to contribute to a positive environmental change [8,9,11,12,28,30,31,32].

Aleixo and colleagues [33] analyzed students’ perceptions of sustainable development, illustrating that, although students recognize the importance of sustainable development and have heard about sustainable development goals, they believe that higher education institutions should provide more training (i.e., courses) on this topic. However, these studies do not include the role of universities in curriculum development, including sustainability courses or evaluating students’ values, norms, or beliefs about the natural environment. By compiling and formulating appropriate curricula and course plans, universities and individual programs can shape students’ beliefs with specific provisions (e.g., environmental sustainability). Today’s students will be the prominent influencers and decision-makers of the future; thus, a greater understanding of students’ beliefs and attitudes toward sustainable development is needed.

The emergence of complex global challenges demands that our students be prepared for a world threatened by unstable climate change and inequity. The role of universities is critical in helping society to identify and solve both local and global problems regarding sustainable development. Interest must grow among higher education institutions and faculties in regard to offering opportunities for environmental education and better understanding what students want to learn about sustainability both in general and, more specifically, in regard to sport. There are rich resources for students, faculty, departments, and industry members to their expand knowledge on the subject that are easily accessible [7,8,32,34]. These textbooks and case studies can assist educators in overcoming some of the prevalent obstacles in integrating environmental sustainability into sport management programs [8,28]. Lastly, the Sport Ecology Group has played a significant role in promoting and teaching sustainability in sport. The group offers resources such as course syllabi, teaching slides, and a list of readings (all publicly available free of charge) for students and educators alike to increase awareness and knowledge of environmental sustainability issues.

2.3. Value–Belief–Norm Theory of Environmentalism

This research utilized the Value–Belief–Norm theory (VBN) [35] to evaluate individual environmentally significant behaviors. VBN was conceived, adapted, and formed using the following three standalone theories and paradigms: value theory [36], the new ecological paradigms (NEPs) [37], and norm activation theory (NAT) [38]. Simply stated, the theory suggests that personal environmental values influence beliefs about the state of the natural environment, which form personal pro-environmental norms and, ultimately, lead to pro-environmental actions and behaviors (Figure 1). Each variable in the chain directly affects the next and may also influence variables further down the chain [35]. Whitley and colleagues (2018) examined higher education students’ environmental sustainability habits using VBN and found that their values significantly influenced ecological behaviors. They noted that, although VBN is frequently used in research, it is rarely used to evaluate the environmental perspectives of students in higher education.

Considering the proliferation of environmental efforts and awareness around such issues, we propose that the causal relationship between values, beliefs, and norms and behavior has increased since Casper and Pfahl’s original study [7]. Additionally, beyond Casper and Pfahl’s study, we anticipate that sport management students’ values, beliefs, and norms significantly influence their expectations of sport organizations in regard to engaging in environmentally sustainable practices.

2.4. Personal Values

Values are circumstances transcending convictions about what is crucial in one’s life [39]. Concerning the natural environment, ecological values orient a person, influencing their inclination to endorse environmental actions [7,40]. Stern and colleagues drew on the value measures developed by Schwartz and colleagues [36,41] and used them and amendments to establish the VBN theory. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic human values [39] addresses the essence of values, describes the characteristics common to all values, and explains what separates one value from another. Schwartz [39] explains that values can describe people, cultures, and groups within a culture, track changes over time, and explain the motivational foundations of attitudes and behavior.

2.5. Beliefs

VBN suggests that people’s worldviews or beliefs about how the planet and humans interact drive their environmental behavior [7,42]. Stern and colleagues [43] utilized the NEPs to assess individuals’ ecological beliefs. The original NEP [37] was revised in response to criticisms to be focused on 15 statements measuring environmental beliefs, values, and attitudes [44,45]. The revised NEP [35] is highly used in research and is the most popular and widely used measurement of environmental beliefs worldwide [44,45].

Harraway and colleagues [46] used the revised NEP to monitor the development of New Zealand students’ ecological worldviews. Higher education institutions are interested in its impact and the life experiences that shape students’ ecological views but lack the processes to track the changes over time. The revised NEP was delivered twice a semester, and the results indicate changes in the students’ ecological views. While standard assessment methods can easily measure subject matter knowledge, the authors contend that they may not accurately assess values, attitudes, and behaviors. The NEP can help educators regularly evaluate the extent to which their curricula have changed the affective ecological characteristics of cohorts of students.

2.6. Norms

To understand the influences of more common movement support, Stern and colleagues looked to Schwartz’s [38] moral norm-activation theory of altruism (NAT), which suggests that norms are the most significant predictor of environmental behaviors. Schwartz’s theory of altruism indicates that people are more willing to embrace behaviors (including pro-environmental) if the individual is aware of harmful consequences (ACs) to others and when that individual ascribes responsibility (AR) to themselves for altering the offending environmental situation or condition [47]. Personal norms are used to gauge how personally accountable an individual is to the environment and natural resources [7,48]. Actions and behaviors are activated when individuals feel impending harm to other people, species, and the biosphere due to an ecological condition [43]. This is when knowledge becomes essential in bridging the gap between norms and behaviors or awareness and action.

2.7. Behaviors

VBN proposes that personal values, beliefs, and norms form a causal chain to predict personal environmental behaviors and beliefs about the organization’s environmental behaviors. Stern [35] defined environmental behaviors as those that create an impact through direct (e.g., clearing a forest, landfill waste, car emissions) or indirect (e.g., tax policies, legislature, world markets) change to the environment. However, since the environment has become part of humans’ decision-making process with environmentalism, a second definition of environmental behavior has surfaced. The second definition is “behavior that is undertaken with the intention to change (normally, to benefit) the environment” [35], p. 408. Both definitions are important to research. However, using the impact-oriented definition to recognize and target behaviors with the most significant environmental impact is essential [35,42].

For example, regarding personal behaviors, most behavioral studies in the sport sector focus on fan behaviors [6]. Casper and colleagues [49] found that fans expected athletic departments to engage in environmentally friendly behaviors and that departments implementing sustainable initiatives increased home game pro-environmental behaviors. Additionally, McCullough and Cunningham [50] explained that social and internal pressures from stakeholders could encourage sport organizations to adopt ecologically friendly practices. To this point, sport management students represent current fans and future sport management professionals who may be able to influence sustainable change within the sport industry.

2.8. Awareness

The VBN theory considers awareness a significant variable and theorizes that it is an essential predictor of environmental behaviors and an important explanatory component. The term “awareness” refers to a person’s comprehension of the fundamental parts of a problem, not simply being aware that one exists. Although there is a link between environmental awareness and action, research indicates that knowledge is a crucial link between the two factors (see [7]). Knowledge creates a deeper awareness of the significant components of an issue and strengthens the individual’s desire to act.

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Data Collection Process

Data were collected from 510 undergraduates (n = 352) and graduates (n = 157) enrolled in sport management programs at higher education institutions in North America (NA). Demographic data included college level, age (range), gender, and state of institution attended (see Table 1). We utilized an online self-administered survey as the method of data collection. Various faculty in sport management programs in NA were contacted via professional e-mail addresses and invited to assist in distributing surveys to the students in their classes. Students were contacted through their institution’s e-mail account, and a link was provided to the Qualtrics survey, Internal Review Board (IRB) approval, and information about the study. Additionally, the public listserv from the North American Society for Sport Management (NASSM) was utilized to ask the NASSM community to distribute the survey in their classrooms after explaining the research’s purpose and importance. The corresponding author’s institution granted IRB approval.

Table 1.

Demographic Information of Participants (N = 510).

3.2. Measurement Variables

We adopted 29 questions across five constructs from Casper and Pfahl’s study [7] (see Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). Participants were asked to respond using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Personal biospheric values (i.e., pollution prevention, protecting the environment and preserving nature, respecting the Earth, unity with nature) were assessed using four items from Schwartz [36]. The participant’s ecological beliefs were assessed using six items from the revised NEP (i.e., balance of nature, limits to growth, humans over nature) from Dunlap [37,44]. Norms were assessed using six items related to the participant’s connection to environmental conservation, preserving natural resources, and personal responsibility regarding leadership and personal consumption from Casper and Pfahl [7]. Nine items assessing personal behaviors in two categories (e.g., environmentally responsible purchasing resource reduction) were adopted from Scherbaum [48]. Four items were evaluated, and the beliefs were adopted from Casper and Pfahl [7]. This includes the businesses’ strategic planning, operations, and influence on employee behavior. Three new items were added to consider other constructs (i.e., fan identification emotions related to sport). The items specific to beliefs on environmental sport organization behavior were adapted and modified from Stern [43] for a sport context. Four items assessed student awareness of sport organization sustainable behaviors, which were adapted and modified from Casper [7]. Eight new items assessed students’ awareness of sport sustainability in higher education curricula, and three items evaluated the student’s interest in the topic (see Table 3 and Table 4). The items were trichotomous (i.e., yes–no–unsure).

Table 2.

VBN Survey Questions, Constructs, and Statistics (N = 508).

Table 3.

Environmental Awareness Questions and Results.

Table 4.

Environmental Interest Questions and Results.

3.3. Analysis

A total of 523 survey responses were collected, with 510 of them being viable and included in the data analysis. Participants represented higher education institutions in 23 states and resided in 42 states in North America. Table 1 illustrates the demographic profiles of the participants. Scores for the responses within each sub-scale of the six measurement variables (three input and three output variables) were averaged. The sub-scale averages were used in the analysis. The Cronbach Alpha test assessed each sub-scale of Likert-style questions within the six constructs for reliability. Five of the six scales tested had a Cronbach Alpha of over 0.8. Only beliefs (0.737) fell below 0.8, which is still above the 0.6 acceptable level in social sciences [51]. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviation, percentages, frequencies, skewness, and kurtosis) were calculated for all data using SPSS 27. Table 2 provides the survey questions and descriptive statistical results. Pearson r correlations were moderate to moderate/high and all significant (p < 0.01). All analyses were set at a 0.05 alpha level. Lastly, data were run in AMOS 28 to test the structural model (structural equation modeling) and determine the current relationships between the input and output variables.

4. Results

4.1. Structural Modeling of Variables

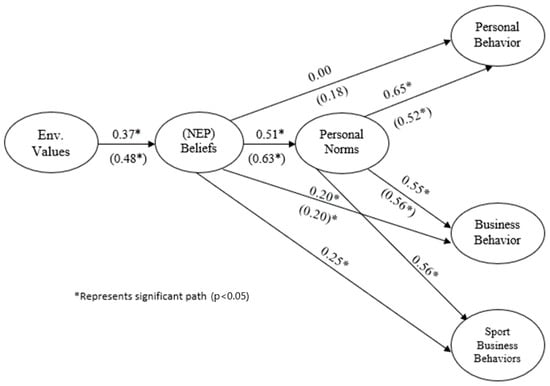

The structural equation modeling analyzed the relationship between the input and output variables (see Figure 1). Like Casper and Pfahl [7], in addition to looking at the direct relationship between the constructs (values, beliefs, norms, and behaviors), the relationship between beliefs and the three behavior constructs was also analyzed. The overall chi-square statistic for the model was significant x2 (7.510) = 417.468, p < 0.000. All relationships (paths) were significant, except for the belief–personal behavior path, including the new constructs of sport organization environmental behaviors (Figure 2). Regarding the new output variable, beliefs and norms were significant predictors of students’ beliefs on the sustainable behaviors of sport organizations. Norms strongly predicted environmental behaviors (personal, business, sport organizations).

Figure 2.

Results from Structural Model testing in 2022, with 2012 results in parentheses.

4.2. Environmental Sustainability Awareness and Interest

Students were asked about their awareness and participation in environmental sustainability initiatives at sporting events. In total, 72.9% of the participants noticed environmental sustainability promotions at events, while 83.7% participated in sustainable initiatives. Furthermore, 71.4% indicated they want to work for a sport organization that promotes and practices environmental sustainability. However, only 22% of the students reported a willingness to pay more for a sport ticket to support environmental sustainability programs (see Table 3).

From an educational perspective, 8.2% of all students reported that their institution had a standalone environmental sustainability course when asked about environmental sustainability education opportunities in their sport management programs. Similarly, 12.2% of students reported that they had taken a class related to environmental sustainability. However, when asked if a professor or guest lecturer had spoken about the topic in a sport management class, the percentage of affirmative responses increased to 19.6%. Participants were asked three questions regarding their interest in environmental sustainability curricula (see Table 3). Regarding interest, 45.4% (n = 232) of the students believed an environmental sustainability course should be offered. When asked about a class offering, 47.1% of students (n = 240) responded that they would take the course if offered because they (52.3%, n = 267) believe it is essential for their future professional careers (see Table 4).

5. Discussion

We proposed that the strength of the relationship between the VBN constructs would increase based on two factors. First, over the past ten years, climate change and environmental awareness have become topics of discussion in political arenas and higher education classrooms [52]. Therefore, one can expect that institutions have developed curricula and coursework that would expose students to these topics. Second, Casper and Pfahl [7] evaluated students’ values, beliefs, and norms in relation to the environment, utilizing a sample of undergraduates. Our study expanded the scope of Casper and Pfahl’s work by including undergraduate and graduate students across North America. Recent findings from Pelcher and colleagues [53] indicated that sport management graduate students have stronger environmental values, beliefs, norms, and behaviors than undergraduate students. Consequently, it was logical to expect the ecological beliefs of students to have become stronger over the past ten years. Furthermore, data from this study indicated that sport management students expect even higher environmental stewardship from sport organizations than traditional business entities. They want to work for an environmentally conscious organization and feel sustainable knowledge is important to their futures. Nevertheless, the results of this study showed that the strengths of the relationships were similar (and in some cases lower) than Casper and Pfahl’s earlier work (2012), thus presenting the question as to why values, beliefs, and norms of sport management students would remain the same over ten years despite the proliferation of environmental efforts within the sport industry. This study implies that, despite the sport industry’s rapid advancement in adopting environmental sustainability practices, new professionals entering the field may lack sufficient preparation to effectively address the sector’s increasingly complex environmental challenges [6]. Consequently, faculty in sport management must push for curriculum improvements and develop closer relationships with the industry. A possible explanation may be that the relationship between values–beliefs and then beliefs-norms was significant but not as strong as the results in 2012, while beliefs–business behaviors, beliefs–personal behaviors, and personal norm–business behaviors were significant. The one distinct difference between the findings of both studies (2012 and this one) is that the relationship between belief-business behaviors is significant, suggesting that students have higher expectations about the environmental behaviors of businesses. Also, as research has indicated, there is a lack of environmental sustainability classes in sport management programs [27,29]. Not much progress may have occurred over the last ten years in regard to curriculum improvements to ensure that students are exposed to sustainability topics through standalone courses or modules being incorporated into various classes (e.g., finance, ethics, marketing, event management, facility management).

The outcomes of both studies indicated that personal norms were more significant predictors of environmental behaviors than beliefs. Values can be compared to awareness, and there was a strong to moderate awareness of the importance of environmental sustainability. The moderate to strong connection continued from values into beliefs that action should be taken to protect the natural environment. Beliefs transitioned to norms and behaviors. These results agree with Schwartz’s [38] moral norm-activation theory, which suggests that norms are the most significant predictor of environmental behaviors. This is when knowledge becomes essential to bridge the gap between norms and behaviors. Higher education institutions can shape students’ beliefs and values through leadership, examples, and curricula offered. Suppose current course offerings or certifications limit special topic courses and that sustainability is not being addressed in the classroom. In that case, it should not be surprising that the results from Casper and Pfahl’s work and this study are not different.

5.1. Awareness and Interest

The development of environmental awareness is part of the professional socialization process for sport management students [7]. Faculty must assess students’ environmental awareness before designing curricula to help students develop appropriate knowledge and skills before entering the professional sport arena [27]. The literature shows a connection between awareness, knowledge, and action [14], but there is limited research regarding sport management students. According to Casper and Pfahl [7], awareness of an issue does not necessarily equate to knowledge. In conjunction with knowledge, the issue’s importance to the individual determines action. Therefore, although a student may be aware of the environmental issues in sport, without a connection between education, context, perspective, and knowledge, action may not be undertaken [53]. This is evident in this study, as less than 25% of the respondents indicated they would pay a higher price for tickets to support environmental sustainability programs.

Although students reported a high awareness of environmental sustainability initiatives at sporting events, responses were vastly different regarding awareness of sustainability curricula in their higher education institutions. Only 42 students reported that their institution had a standalone environmental sustainability course or that they had taken a class related to environmental sustainability. However, positive responses increased when asked if a professor or guest lecturer had spoken about the topic in a sport management class. These results support Graham and colleagues’ [29] findings, whose research exhibited the gap between environmental sustainability and sport management education. The findings illustrated that sport management programs offer few standalone environmental sustainability courses. However, instructors are finding ways to incorporate environmental sustainability modules into existing classes, which could explain the students’ responses.

Students are aware of environmental initiatives at sport events but unaware of educational opportunities for sustainable education in their institutions. Moreover, they are interested in sustainable education and believe it is vital to their professional futures. Therefore, the pressing question is whether academia is missing a golden opportunity to prepare future sport industry leaders by not shaping the environmental values, beliefs, and norms of the next generation of sport managers.

5.2. Recommendations

Communication and knowledge exchange will be needed to bridge the gap between higher education and the sport industry for enhanced environmental education. Feedback and suggestions from the sport industry that can be shared with educators and students may stimulate a greater desire to learn more about the topic. While there are known barriers to implementing environmental sustainability education in sport management programs (see [27,28,29]), such as lack of expertise on the subject, human and educational resources relating to environmental sustainability are available today. However, what seems to be most disconcerting is the juxtaposition of organizational effort to engage in environmental sustainability, the desires of students, and the courses that sport management programs offer focused on environmental sustainability [29]. The sport management academia must consider its offerings and curriculum modifications and development. It may behoove the field to offer classes in environmental sustainability or other topics that are most pressing and influential on the business of sport. Much like the proliferation of diversity, equity, and inclusion courses in sport management, environmental sustainability and related topics need to be more broadly discussed and incorporated into the classroom if we are to prepare students not only for the careers they will be entering upon graduation but for the pressing issues that they will be inheriting in the immediate and near future.

The instigation of incorporating lessons and dedicated classes on new, emerging, and pressing sport industry topics will not emerge from the student body alone—the professoriate must recognize its place to drive this interest by pushing such topics into the curriculum. Our students may not want to take specific courses for various reasons, but topics must be broached, whether uncomfortable or exploratory. Such pushes will advance our field to grow and, in the instance of diversity, equity, and inclusion, be more socially just, as well as, in the case of environmental sustainability, help our industry avoid endangerment or extinction [11,54].

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Due to the ecological subject matter, it is possible that social desirability bias could have impacted responses by answering questions in a manner that they believe would be viewed favorably by others. Even though the survey was online and anonymous, participants may have over-reported their environmental beliefs and behaviors, which could have resulted in higher value inputs. Similarly, acquiescence (yea-saying) and extreme response bias must be considered, as should the tendency to use extreme options on a Likert Scale [55]. Additionally, students were asked about personal sustainable behaviors and future behaviors; therefore, subjectivity based on their level of sustainable knowledge must be considered. Due to the limited amount of research using VBN to evaluate students in higher education, the findings of this research are essential in establishing a basis for future research. Scholars can evaluate changes over time as more educational and professional opportunities related to environmental sustainability become available to students. This means that recurring research will need to be conducted to evaluate if more educational opportunities in sport management curricula are becoming available to students and how this is impacting their environmental knowledge and beliefs. Comparative studies can also be conducted across various geographic regions or within different educational contexts. Future longitudinal studies could assess if additional expertise on environmental sustainability promotes pro-environmental behaviors. This could be achieved by including more open-ended, qualitative questions asking students to elaborate on specific responses, which may identify the best predictors and catalysts for environmental actions. Lastly, it would be beneficial to examine the specific skills and training potential employers (in the sport industry) are looking for and the suggestions they may have as to what actions are necessary to address the gap between environmental knowledge and the expectations of the industry.

6. Conclusions

Future sport management professionals will need to learn about the environment in order to be successful in the sport sector. The findings of this study suggest that educators and facilitators at higher education institutions may be missing a significant opportunity to educate the next generation of sport managers on the importance of implementing and promoting environmental sustainability in sport. As educators in sports management, we have a unique opportunity and responsibility to shape the future of our industry by integrating environmental sustainability into our curricula. The increasing awareness and importance of sustainability require us to equip the next generation of sports managers with the knowledge and skills necessary to lead environmentally responsible organizations [9]. While we acknowledge that not every sport management program may have the resources to develop and implement a specific course on environmental sustainability, other approaches could be implemented. For example, sustainability experts could be invited as guest speakers, and courses such as sport marketing or event and facility management can easily incorporate a module on sustainability and connect it to the specific course content [12,29]. Higher education settings must find a way to incorporate environmental educational opportunities in the curricula and address the disconnect between higher education and industry [27,53]. Evaluating sport management students’ awareness of environmental sustainability in sport may aid higher education institutions in developing more effective curricula by increasing human and educational resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.P.; Methodology, J.A.P. and B.P.M.; Software, J.A.P.; Validation, J.A.P., S.T. and B.P.M.; Formal Analysis, J.A.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.A.P.; Writing—Review and Editing, S.T. and B.P.M.; Visualization, J.A.P.; Supervision, S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for open access to this research was provided by University of Tennessee’s Open Publishing Support Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval number from University of Tennessee Knoxville: UTK IRB-21-06398-XM. The Human Research Protections Program (HRPP) reviewed your application for the above referenced project and determined that your application is eligible for exempt review under 45 CFR 46.101.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McCullough, B.P.; Kellison, T. Making our footprint: Constraints in the legitimization of sport ecology in practice and the academy. In Sport and the Environment; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, B.P.; Orr, M.; Kellison, T. Sport ecology: Conceptualizing an emerging subdiscipline within sport management. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 34, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, B. Bushfire Smoke Causes Player to Forfeit Her Qualifying Match for the Australian Open; NPR: Washington, DC, USA, 14 January 2020; Available online: https://www.npr.org/2020/01/14/796234327/bushfire-smoke-causes-player-to-forfeit-her-qualifying-match-for-australian-open (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Sorrentini, F. The environmental impact of sports activities. Good practices for sustainability: The case of golf. Doc. Geogr. 2022, 2, 219–237. [Google Scholar]

- Dingle, G.; Dickson, G.; Stewart, B. Major sport stadia, water resources, and climate change: Impacts and adaptation. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2023, 23, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, S.; McCullough, B.P. Environmental sustainability scholarship and the efforts of the sport sector: A rapid review of literature. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.M.; Pfahl, M.E. Environmental behavior frameworks of sport and recreation undergraduate students. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2012, 6, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, W.J. On the necessity of teaching sport ecology. Case Stud. Sport Manag. 2022, 11, SE1–SE2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, W.J.; Mercado, H. Barriers to managing environmental sustainability in sport and entertainment venues. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L. Toward a distinctive sport management discipline. J. Sport Manag. 2006, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallen, C.; Chard, C. A framework for debating the future of environmental sustainability in the sport academy. Sport Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, M.; McCullough, B.P.; Pelcher, J. Leveraging sport as a venue and vehicle for transformative sustainability learning. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cury, R.; Kennelly, M.; Howes, M. Environmental sustainability in sport: A systematic literature review. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2023, 23, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, C.T.; Takahashi, B.; Zwickle, A.; Besley, J.C.; Lertpratchya, A.P. Sustainability behaviors among college students: An application of the VBN theory. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.; Pfahl, M.; McSherry, M. Athletics department awareness and action regarding the environment: A study of NCAA athletics department sustainability practices. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Cunliffe, A.L.; Easterby-Smith, M. Understanding sustainability through the lens of ecocentric radical-reflexivity: Implications for management education. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, H.; Lindgreen, A. Sustainability, epistemology, ecocentric business, and marketing strategy: Ideology, reality, and vision. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammelsæter, H.; Loland, S. Code Red for Elite Sport. A critique of sustainability in elite sport and a tentative reform programme. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2023, 23, 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynaghi, A.; Trencher, G.; Moztarzadeh, F.; Mozafari, M.; Maknoon, R.; Leal Filho, W. Future sustainability scenarios for universities: Moving beyond the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3464–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Education Is Key to Addressing Climate Change; United Nations: New York, NY, USA n.d. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/climate-solutions/education-key-addressing-climate-change (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Horhota, M.; Asman, J.; Stratton, J.P.; Halfacre, A.C. Identifying behavioral barriers to campus sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2014, 15, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramatakos, A.L.; Lavau, S. Informal learning for sustainability in higher education institutions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seatter, C.S.; Ceulemans, K. Teaching sustainability in higher education: Pedagogical styles that make a difference. Can. J. High. Educ. 2017, 47, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trencher, G.; Terada, T.; Yarime, M. Student participation in the co-creation of knowledge and social experiments for advancing sustainability: Experiences from the University of Tokyo. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 16, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J. Student-led action for sustainability in higher education: A literature review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbarth, T.; McCullough, B.P.; Collins, A.; Gerke, A.; Herold, D.M. Environmental matters in sport: Sustainable research in the academy. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2023, 23, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, H.U.; Grady, J. Teaching environmental sustainability across the sport management curriculum. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2017, 11, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingle, G.W.; Mallen, C. Sport-environmental sustainability (Sport-ES) education. In Routledge Handbook of Sport and the Environment; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J.; Trendafilova, S.; Ziakas, V. Environmental sustainability and sport management education: Bridging the gaps. Manag. Sport Leis. 2018, 23, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ličen, S.; Jedlicka, S.R. Sustainable development principles in US sport management graduate programs. Sport Educ. Soc. 2020, 27, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallen, C.; Adams, L.; Stevens, J.; Thompson, L. Environmental sustainability in sport facility management: A Delphi study. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2010, 10, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingle, G.; Mallen, C. Sport and education for environmental sustainability. In Sport and Environmental Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 243–260. [Google Scholar]

- Aleixo, A.M.; Leal, S.; Azeiteiro, U.M. Higher education students’ perceptions of sustainable development in Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 327, 129429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M. Sustainable development goals and capability-based higher education outcomes. Third World Q. 2022, 43, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “New Environmental Paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Bilsky, W. Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G.; Van der Werff, E.; Lurvink, J. The significance of hedonic values for environmentally relevant attitudes, preferences, and actions. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E. The new environmental paradigm scale: From marginality to worldwide use. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 40, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, B.E.; Hushen, K.; McGinty, D.; Perkins, S.; Tate, J. Endorsement of the new ecological paradigm in systematic and e-mail samples of college students. J. Environ. Educ. 2005, 36, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harraway, J.; Broughton-Ansin, F.; Deaker, L.; Jowett, T.; Shephard, K. Exploring the revised new ecological paradigm scale (NEP) to monitor the development of students’ ecological worldviews. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 43, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherbaum, C.A.; Popovich, P.M.; Finlinson, S. Exploring individual-level factors related to employee energy-conservation behaviors at work 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.M.; Pfahl, M.E.; McCullough, B.P. Is going green worth it? Assessing fan engagement and perceptions of athletic department environmental efforts. J. Appl. Sport Manag. 2017, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, B.P.; Cunningham, G.B. A conceptual model to understand the impetus to engage in and the expected organizational outcomes of green initiatives. Quest 2010, 62, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, M.M.; Sulaiman, N.L.; Sern, L.C.; Salleh, K.M. Measuring the validity and reliability of research instruments. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 204, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerlich, B.; McLeod, C. The dilemma of raising awareness “responsibly” and the need to discuss controversial research with the public raises a conundrum for scientists: When is the right time to start public debates? EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelcher, J.; Trendafilova, S.; Graham, J.A. An evaluation of the environmental values, beliefs, norms, and behaviors of sport management students in higher education institutions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2023, 24, 1687–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Steiger, M.; Rutty, M.; Johnson, R. The future of the Olympic Winter Games in an era of climate change. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 910–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).