Nepali Migrant Workers and Their Occupational Health Hazards in the Workplace: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Nepali migrant workers working abroad;

- Workplace hazards, injuries, and risks faced by Nepali migrant workers in working abroad;

- Peer-reviewed publications, either quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research;

- Literature published up to July 2024;

- Only publications in the English language.

- Studies conducted with non-migrant workers or internal migrant workers and their workplace hazards;

- Studies not in the English language;

- Systematic reviews, scoping reviews, book chapters, editorials, or commentaries.

3. Results

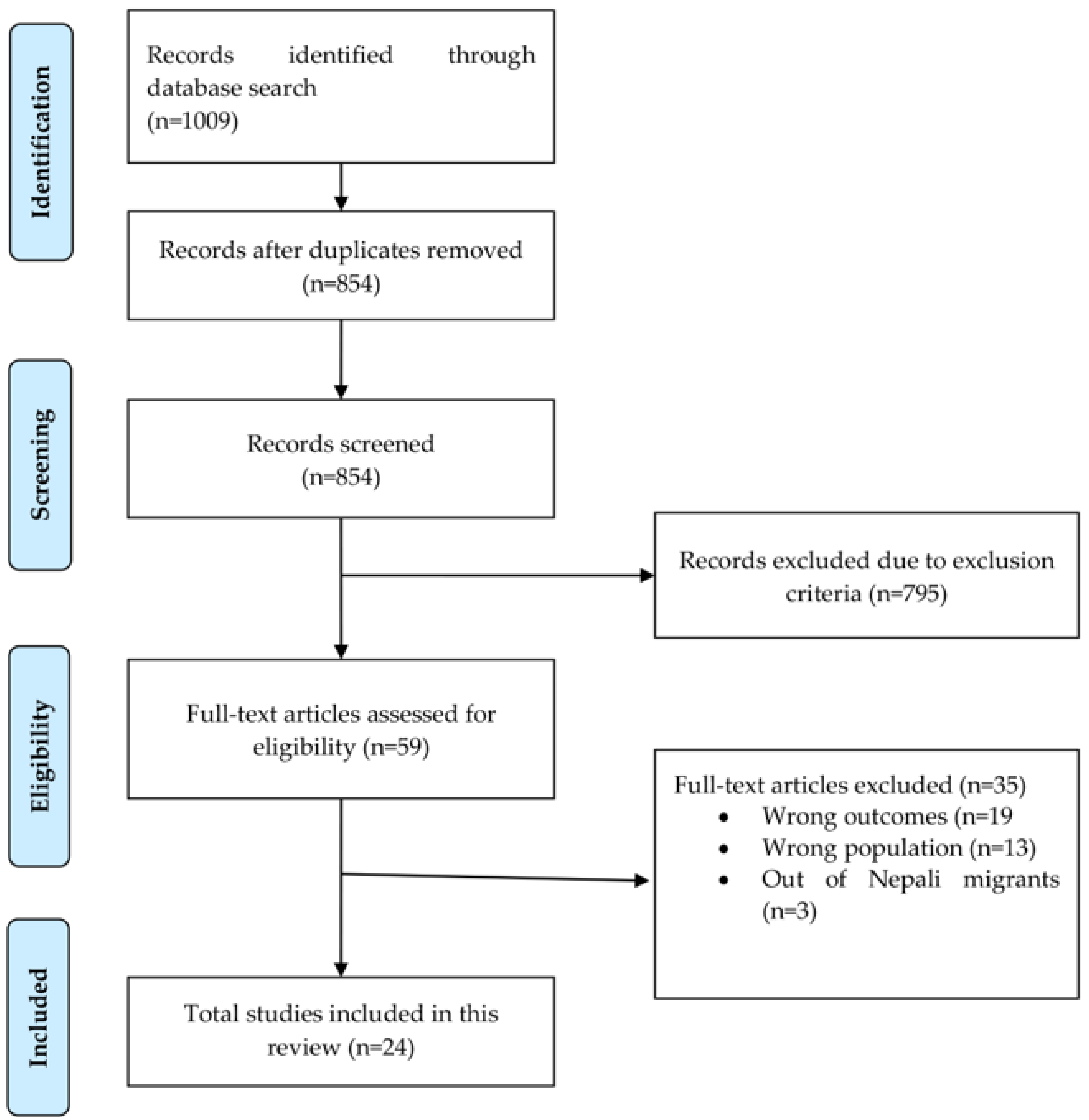

3.1. Identification and Selection of the Articles

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Studies Exploring Occupational Hazards in the Workplace

3.3.1. Poor Working Environment

3.3.2. Injuries Risks and Safety

3.3.3. Discriminatory Behaviours

3.3.4. Psychosocial Hazards

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Policy and Practice

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Leaving No One Behind: Equality and Non-Discrimination at the Heart of Sustainable Development the United Nations System Shared Framework for Action; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report; Katila, P., Colfer, C.J.P., De Jong, W., Galloway, G., Pacheco, P., Winkel, G., Eds.; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Norredam, M.; Agyemang, C. Tackling the health challenges of international migrant workers. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e813–e814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nation. International Migration Report 2017-Highlights. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2017_Highlights.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- World Health Organization. Promoting the Health of Refugees and Migrants: Experiences from around the World. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/366326/9789240067110-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Simkhada, P.; van Teijlingen, E.; Regmi, P. Migrant Workers in Qatar: Not just an important topic during the FIFA World Cup 2022. Health Prospect. J. Public Health 2022, 21, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfani, A. Kicking away responsibility: FIFA’s role in response to migrant worker abuses in Qatar’s 2022 World Cup. Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports LJ 2015, 22, 623. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistics Office. The National Population and Housing Census 2021: National Report: Volume 01. Available online: https://censusnepal.cbs.gov.np/results/files/result-folder/National%20Report_English.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- MoLE. Labour Migration for Employment. A Status Report for Nepal: 2015/2016–2016/2017. Available online: https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Nepal-Labor-Migration-status-report-2015-16-to-2016-17.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Pant, R.K. The trends of foreign employment and remittance inflow in Nepal. Journey Sustain. Dev. Peace J. 2024, 2, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOLESS. Nepal Labour Migration Report 2022; Ministry of Labour, Emplyment and Social Security: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer, J. Envisioning futures at new destinations: Geographical imaginaries and migration aspirations of Nepali migrants moving to Malta. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2024, 50, 3049–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, P.; Wasti, S.P.; Neupane, P.; Kulasabanathan, K.; Silwal, R.C.; Pathak, R.S.; Memon, A.; Watts, C.; Sapkota, J.; Magar, S.A. Health and wellbeing of Nepalese migrant workers in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries: A mixed-methods study. J. Migr. Health 2023, 7, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudyal, P.; Kulasabanathan, K.; Cassell, J.A.; Memon, A.; Simkhada, P.; Wasti, S.P. Health and well-being issues of Nepalese migrant workers in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries and Malaysia: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucci, N.; Traversini, V.; Giorgi, G.; Garzaro, G.; Fiz-Perez, J.; Campagna, M.; Rapisarda, V.; Tommasi, E.; Montalti, M.; Arcangeli, G. Migrant workers and physical health: An umbrella review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Simkhada, P.; Prescott, G.J. Health problems of Nepalese migrants working in three Gulf countries. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2011, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravensbergen, S.J.; Nellums, L.B.; Hargreaves, S.; Stienstra, Y.; Friedland, J.S. National approaches to the vaccination of recently arrived migrants in Europe: A comparative policy analysis across 32 European countries. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 27, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, M.; Zendel, A.; Biggar, J.; Frederiksen, L.; Wells, J. Migrant Work & Employment in the Construction Sector; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant, M.; Tucker, E. Layers of vulnerability in occupational safety and health for migrant workers: Case studies from Canada and the UK. Policy Pract. Health Saf. 2009, 7, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkhada, P.; Van Teijlingen, E.; Gurung, M.; Wasti, S.P. A survey of health problems of Nepalese female migrants workers in the Middle-East and Malaysia. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2018, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, N.; Regmi, P.R.; van Teijlingen, E.; Simkhada, P.; Adhikary, P.; Bhatta, Y.K.; Mann, S. Injury and mortality in young Nepalese migrant workers: A call for public health action. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2016, 28, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasti, S.P.; Shrestha, A.; Atteraya, M.S. Migrants workers health-related research in Nepal: A bibliometric review. Dialogues Health 2023, 3, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergnes, J.-N.; Marchal-Sixou, C.; Nabet, C.; Maret, D.; Hamel, O. Ethics in systematic reviews. J. Med. Ethics 2010, 36, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consunji, R.; El-Menyar, A.; Hirani, N.; Abeid, A.; Al-Thani, H.; Hardan, M.S.; Chauhan, S.; Kasem, H.; Peralta, R. Work-related injuries in Qatar for 1 year: An initial report from the work-related injury unified registry for Qatar. Qatar Med. J. 2022, 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Kjellstrom, T.; Atar, D.; Sharma, P.; Kayastha, B.; Bhandari, G.; Pradhan, P.K. Heat stress impacts on Cardiac Mortality in Nepali migrant workers in Qatar. Cardiology 2019, 143, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sayyad, A.S.; Hamadeh, R.R. The burden of climate-related conditions among laborers at Al-Razi Health Centre, Bahrain. J. Bahrain Med. Soc. 2014, 25, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al-Thani, H.; El-Menyar, A.; Consunji, R.; Mekkodathil, A.; Peralta, R.; Allen, K.A.; Hyder, A.A. Epidemiology of occupational injuries by nationality in Qatar: Evidence for focused occupational safety programmes. Injury 2015, 46, 1806–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, S. Building Hong Kong: Nepalese labour in the construction sector. J. Contemp. Asia 2004, 34, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, R.; El-Menyar, A.; Al-Thani, H.; Zarour, A.; Parchani, A.; Abdulrahman, H.; Asim, M.; Peralta, R.; Consunji, R. Traffic-related pedestrian injuries amongst expatriate workers in Qatar: A need for cross-cultural injury prevention programme. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2015, 22, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, N.N.; Vasudevan, S.K.; Jasman, A.A.; Aisyahbinti, A.; Myint, K.T. Work-related ocular injuries in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. Int. Eye Sci. 2016, 16, 416–422. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary, P.; Sheppard, Z.; Keen, S.; van Teijlingen, E. Risky work: Accidents among Nepalese migrant workers in Malaysia, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Health Prospect. 2017, 16, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, P.; Sheppard, Z.A.; Keen, S.; Teijlingen, E.v. Health and well-being of Nepalese migrant workers abroad. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2018, 14, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Adhikari, R.; Parajuli, E.; Buda, M.; Raut, J.; Gautam, E.; Adhikari, B. Psychological morbidities among Nepalese migrant workers to Gulf and Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0267784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunam, R. Infrastructures of migrant precarity: Unpacking precarity through the lived experiences of migrant workers in Malaysia. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2023, 49, 636–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Leung, M.-y.; Ojo, L.D. An exploratory study to identify key stressors of ethnic minority workers in the construction industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, H.R.; Bhandari, B.; Adhikary, P. Perceived mental health, wellbeing and associated factors among Nepali male migrant and non-migrant workers: A qualitative study. J. Migr. Health 2021, 3, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regmi, P.R.; Aryal, N.; Van Teijlingen, E.; Simkhada, P.; Adhikary, P. Nepali migrant workers and the need for pre-departure training on mental health: A qualitative study. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 22, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikary, P.; Keen, S.; Van Teijlingen, E. Workplace accidents among Nepali male workers in the Middle East and Malaysia: A qualitative study. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regmi, P.R.; Teijlingen, E.V.; Mahato, P.; Aryal, N.; Jadhav, N.; Simkhada, P.; Zahiruddin, Q.S.; Gaidhane, A. The health of Nepali migrants in India: A qualitative study of lifestyles and risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atteraya, M.S.; Ebrahim, N.B.; Gnawali, S. Perceived risk factors for suicide among Nepalese migrant workers in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman-Thompson, B. Theorising violence in mobility: A case of Nepali women migrant workers. Fem. Theory 2023, 24, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Ghimire, A.; Khor, Y. Living at work: Migrant worker dormitories in Malaysia. Work. Glob. Econ. 2024, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Kilby, P.; Mathema, J.; Bhattarai, A. The precarity of women’s short-term migration: A case study from Nepal. Migr. Dev. 2023, 12, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Murad, A.; Shamsuddin, R. Illuminating causes and barriers underpinning forced labour in Nepal-Malaysia migration corridor. J. Strateg. Stud. Int. Aff. 2023, 3, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Government of Nepal. Nepal Labour Migration Report 2022. Available online: https://moless.gov.np/np/post/show/501 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Simkhada, P.P.; Regmi, P.R.; Van Teijlingen, E.; Aryal, N. Identifying the Gaps in Nepalese Migrant Workers’ Health and Well-Being: A Review of the Literature. J. Travel Med. 2017, 24, tax021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, I.; Have Qatar’s Work Conditions Improved? Migrant Labourers Tell Their Stories. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/14/for-qatars-foreign-workers-global-scrutiny-working-to-a-point (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Regmi, P.; Aryal, N.; Simkhada, P.; van Teijlingen, E. Excessive mortalities among migrant workers: The case of the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Eur. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 4, 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldenmund, F.; Cleal, B.; Mearns, K. An exploratory study of migrant workers and safety in three European countries. Saf. Sci. 2013, 52, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, S.; Rustage, K.; Nellums, L.B.; McAlpine, A.; Pocock, N.; Devakumar, D.; Aldridge, R.W.; Abubakar, I.; Kristensen, K.L.; Himmels, J.W. Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e872–e882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, N.; Shah, D. SAT-136 Chronic kidney disease in migrant workers in Nepal. Kidney Int. Rep. 2020, 5, S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pattisson, P.; Acharya, P. ‘Going Abroad Cost Me My Health’: Nepal’s Migrant Workers Coming Home with Chronic Kidney Disease. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/jun/26/going-abroad-cost-me-my-health-nepals-migrant-workers-coming-home-with-chronic-kidney-disease (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Aryal, N.; Regmi, P.R.; Faller, E.M.; van Teijlingen, E.; Khoon, C.C.; Pereira, A.; Simkhada, P. Sudden Cardiac Death and Kidney Health Related Problems Among Nepali Migrant Workers in Malaysia. Nepal J. Epidemiol. 2019, 9, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.J. Migration and health in the construction industry: Culturally centering voices of Bangladeshi workers in Singapore. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapilashrami, A.; John, E.A. Pandemic, precarity and health of migrants in South Asia: Mapping multiple dimensions of precarity and pathways to states of health and well-being. J. Migr. Health 2023, 7, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup Foundation. World Risk Poll 2021: Safer at Work? Global Experiences of Violence and Harassment. Available online: https://wrp.lrfoundation.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-06/LRF_2021_report_safe-at-work.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Demissie, F. Ethiopian female domestic workers in the Middle East and Gulf States: An introduction. Afr. Black Diaspora Int. J. 2018, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shree, M. Victimization of female Indian migrant workers in Gulf countries. In Proceedings of the First International Conference of the South Asian Society of Criminology and Victimology (SASCV), Jaipur, Rajasthan, India, 15–17 January 2011; p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- Hovey, J.D.; Magaña, C.G. Suicide risk factors among Mexican migrant farmworker women in the Midwest United States. Arch. Suicide Res. 2003, 7, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnesty International. Exploitation and Forced Labour of Nepalese Migrant Workers. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/28000/asa310072011en.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Hajariya, A. Nepalese migrant workers and their hardship in the desert. Available online: https://commons.clarku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1108&context=idce_masters_papers (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- MoLESS. Nepal Labour Migration Report 2020; Ministry of Labour Emplyment and Social Security: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, R.; Zhang, C.X.; Patel, P.; Eley, I.; Campos-Matos, I.; Aldridge, R.W. Migration health research in the United Kingdom: A scoping review. J. Migr. Health 2021, 4, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year | Aim of the Study | Study Country, Year | Study Setting | Type of Study | Sample Size | Participants’ Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhikari et al., 2017 [35] | To assess the extent of workplace accidents among Nepali migrant workers in Malaysia, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia | Nepal; 2011 | Kathmandu, Tribhuvan International Airport | Quantitative survey | 403 | Age (range): 45.9% were aged between 20 to 29 years Sex: all male Literacy: 24.6% were illiterate Marital status: 91.3% married Migrant’s working sector: 30.8% were in unskilled jobs. |

| Adhikary et al., 2018 [36] | To assess the health and mental wellbeing of Nepali construction and factory workers employed in Malaysia, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia | Nepal; 2011 | Kathmandu, Tribhuvan International Airport | Quantitative survey | 403 | Age (range): 45.9% were aged between 20 to 29 years Sex: all male Literacy: 24.6% were illiterate Marital status: 91.3% married Migrant’s working sector: 30.8% were in unskilled jobs. |

| Adhikary et al., 2019 [42] | To explore the personal experiences of male Nepali migrants with unintentional injuries at their place of work. | Nepal; 2011 | International Airport and nearby hotels /guesthouses | Qualitative study | 20 | Age (range): mean age 31.3 years (ranged from 20 to 49 years) Sex: all male Literacy: 50% had no education Marital status: 75% were married Migrant’s working sector: NR. |

| Ahmed et al., 2022 [39] | To identify the key stressors faced by ethnic minority construction workers (EM-CWs) and propose practical solutions to manage these stressors in the industry. | Hong Kong; NR | Construction industry | Qualitative study | 13 | Age (range): ranges between 20–59 years old Sex: all male Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: 6 skilled and 7 semi-skilled workers. |

| Al-Sayyad and Hamadeh, 2014 [30] | To measure the burden of climate-related conditions (CRC) on health services in the main labourers’ clinic in the Kingdom of Bahrain | Bahrain; 2008 | Health facility | Quantitative survey | 3715 | Age (range): NR Sex: NR Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: NC. |

| Al-Thani et al., 2015 [31] | To analyse and describe the epidemiology of these injuries based on the worker’s nationality residing in Qatar. | Qatar; 2010–2013 | Trauma centre | Retrospective routine data analysis | 563 | Age (range): mean age was 32 years (10.3) Sex: NC Literacy: NC Marital status: NC Migrant’s working sector: NC. |

| Atteraya et al., 2021 [44] | To delineate the main suicide risk factors for this group of migrants. | Korea; NR | Self-help groups of migrant communities | Qualitative study | 20 | Age (range): ranges between 22 to 41 years Sex: 85% male and 15% female Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: semi-skilled in manufacturing sectors. |

| Consunji et al., 2022 [28] | To describe the work-related injuries and deaths in Qatar. | Qatar; 2020 | Health facility | Retrospective routine data analysis | 44,687 | Age (range): NR Sex: NR, Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: semi-skilled in the construction sector. |

| Devkota et al., 2021 [40] | To explore the mental health and wellbeing experiences of Nepali male returnee migrants. | Nepal; 2020 | Community | Qualitative study | 19 interviews (FGDs—4 and IDIs—15) | Age (range): ranges between 19 to 55 years old Sex: all male Literacy: 72% had secondary level Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: 48% were labourers—security guards, office boys/cleaners. |

| Frost, 2004 [32] | To explore the Nepali migrant’s work-related issues working in Hong Kong. | Hong Kong; 2001 | Community | Quantitative survey | 267 | Age (range): 17% were younger than 25 years old Sex: 88.4% male and 11.6% female Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: 74% of Nepali migrants worked in the construction sector. |

| Grossman-Thomps, 2023 [45] | To explore the violence experience of Nepali women migrant workers abroad. | Nepal; 2016 | Community and virtually (telephone or online) | Qualitative study | 30 | Age (range): NR Sex: All female Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: NR. |

| Jones et al., 2024 [46] | To explore the migrant worker’s work and accommodation in Malaysia. | Malaysia and Nepal; NR | Community | Qualitative study | 104 | Age (range): NR Sex: both male and female migrants including other stakeholders. Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: males worked in service, construction. and agriculture whereas all females worked as factory workers. |

| Joshi et al., 2011 [16] | To explore the health problems and accidents experienced by a sample of Nepali migrants in three Gulf countries. | Nepal; 2009 | InternationalAirport and nearby hotel/guest house | Quantitative survey | 408 | Age (range): mean age 32 (6.5) years Sex: 92.4% male and 7.6% female Literacy: 76.2% had primary-level education Marital status: 80.6% married Migrant’s working sector: majority were semi-skilled—54.9% construction work, and 18.1% household/manual servant. |

| Latifi et al. (2015) [33] | To analyse the traffic-related pedestrian injuries (TRPI) amongst expatriates to RDC. | Qatar; 2009–2011 | Health facility | Retrospective routine data analysis | 4997 | Age (range): NR Sex: NR Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: NR. |

| Min et al. (2016) [34] | To describe the epidemiology of work-related ocular injuries and their visual outcome in a tertiary hospital in southern Malaysia. | Malaysia; 2011–13 | Health facility | Retrospective routine data analysis | 935 | Age (range): ranges 20 to 60 years old Sex: 98.2% were male Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: NR. |

| Paudyal et al., 2023 [13] | To understand the health and wellbeing issues of Nepali migrant workers in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. | Nepal; 2019 | Community | Mixed-methods study | N = 80 (Survey—60 and KIIs 20) | Age (range): median age 34 years, ranges 23–51 years Sex: male 96.7% (n = 58), female 3.3% (n = 2) Literacy: 8.3% (n = 5) had no formal education Marital status: 91.7% (n = 55) currently married Migrant’s working sector: semi-skilled—28.3% manufacturing /factory workers. |

| Pradhan et al., 2019 [29] | To analyse the mortality status due to occupational heat stress working in high ambient temperature and its association with cardiovascular problems (CVP) of Nepali migrant workers in Qatar. | Qatar; 2009–2017 | Community | Retrospective routine data analysis | 1354 | Age: NR Sex: NR Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: NR. |

| Regmi et al., 2019 [43] | To explore issues of accommodation and working environments in the context of health vulnerabilities amongst Nepali migrants in India. | India; 2017 | Community | Qualitative study | 78 | Age (range): ranges 19–50 years Sex: 51.3% (n = 40) male and 48.7% (n = 38) female Literacy: 21.8% were literate Marital status: 91.5% were married Migrant’s working sector: 31.5% security/watchman, 45% domestic workers/cleaners. |

| Regmi et al., 2019 [41] | To identify triggers of mental ill-health among Nepali migrant workers. | Nepal; 2017 | Tribhuvan International Airport | Qualitative study | FGDs—4, IDIs—7 and KIIs—8 | Age (range): ranges between 21 to 53 years Sex: male and female Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: semi-skilled worked in the security and domestic workers. |

| Sharma et al., 2023 [37] | To identify and determine the predictors of psychological wellbeing among Nepali migrant workers in Gulf countries and Malaysia. | Nepal; 2019 | Tribhuvan International Airport | Quantitative survey | 502 | Age (range): mean age—32.97 (7.6) years Sex: male 93% and female 7% Literacy: primary level (35.7%) Marital status: unmarried 18.3% Migrant’s working sector: office workers (7.8%), construction (25.9%), housemaid/housekeeping (8.4%), and security (7%). |

| Simkhada et al., 2018 [20] | To explore the health problems of female Nepali migrants working in the Middle East and Malaysia. | Nepal; 2009–14 | Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) | Retrospective routine data analysis | 1010 | Age (range): median age of 31 Sex: all female returnee migrants Literacy: 37.4% were illiterate Marital status: 24% were unmarried, 20.7% divorced/separated, and 7% were widowed Migrant’s working sector: unskilled in domestic work. |

| Sunam, 2023 [38] | To explore the lived experiences of migrant workers in Malaysia. | Malaysia; 2017–19 | Social network in Malaysia-based Nepali diaspora | Qualitative study | 31 | Age (range): ranged between the ages 20 to 35 years Sex: 26 male and 5 female Literacy: NR Marital status: 80% married Migrant’s working sector: security guards and restaurant workers. |

| Wahab et al., 2023 [48] | To assess the barriers and causes underpinning actual and potential drivers of forced labour involving Nepali workers in Malaysia. | Malaysia; 2021 | Multiple workstations | Mixed-methods study | N = 117 (Survey—76 and in-depth interviews—41) | Age (range): NR Sex: NR Literacy: NR Marital status: NR Migrant’s working sector: unskilled and low-wage labourers. |

| Wu et al., 2024 [47] | To explore precarity in short-term women’s migration using the case study of Nepal. | Nepal; 2022 | Community | Qualitative study | 46 (6 FGD & 12 KIIs) | Age (range): NR Sex: female returnee migrants Literacy: NR, Marital status: NR, Migrant’s working sector: domestic work. |

| Author, Year | Reported Workplace Hazards | Key Findings | Limitations of the Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adhikari et al., 2017 [35] | Workplace accidents and injuries |

|

|

| Adhikary et al., 2018 [36] | Poor workplace environment/general health issues |

| NR |

| Adhikary et al., 2019 [42] | Work-related accidents |

|

|

| Ahmed et al., 2022 [39] | Poor work environment, long working hours, pay differences |

|

|

| Al-Sayyad and Hamadeh, 2014 [30] | Climate-related conditions/heat-related disease |

|

|

| Al-Thani et al., 2015 [31] | Occupation injuries/falls of heavy objects |

|

|

| Atteraya et al., 2021 [44] | Workplace risks factors |

|

|

| Consunji et al., 2022 [28] | Workplace injuries |

| NR |

| Devkota et al., 2021 [40] | Adverse working condition |

|

|

| Frost, 2004 [32] | Payment discrimination/no access to basic facilities (i.e., drinking water, toilet, bathroom) |

| NR |

| Grossman-Thomps, 2023 [45] | Workplace abuses |

|

|

| Jones et al., 2024 [46] | Poor living environment and long working hours |

| NR |

| Joshi et al., 2011 [11,16] | Workplace injuries/accidents |

|

|

| Latifi et al., (2015) [33] | Traffic-related pedestrian injuries |

|

|

| Min et al., (2016) [34] | Eye injuries due to fall of objects |

|

|

| Paudyal et al. 2023 [13] | Work abuse, injuries, sexual violence |

|

|

| Pradhan et al., 2019 [29] | Environmental health and workplace accidents |

|

|

| Regmi et al., 2019 [43] | Workplace injuries/accidents |

|

|

| Regmi et al., 2019 [41] | Maltreatment/discrimination, workplace abuse |

|

|

| Sharma et al., 2023 [37] | Workplace issues |

|

|

| Simkhada et al., 2018 [20] | Workplace abuse/injuries, torture/maltreatment |

|

|

| Sunam, 2023 [38] | Workplace injuries/accidents |

| NR |

| Wahab et al., 2023 [48] | Workplace discriminatory behaviours |

| NR |

| Wu et al., 2024 [47] | Workplace abuse |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wasti, S.P.; Babatunde, E.; Bhatta, S.; Shrestha, A.; Wasti, P.; GC, V.S. Nepali Migrant Workers and Their Occupational Health Hazards in the Workplace: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7568. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177568

Wasti SP, Babatunde E, Bhatta S, Shrestha A, Wasti P, GC VS. Nepali Migrant Workers and Their Occupational Health Hazards in the Workplace: A Scoping Review. Sustainability. 2024; 16(17):7568. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177568

Chicago/Turabian StyleWasti, Sharada Prasad, Emmanuel Babatunde, Santosh Bhatta, Ayushka Shrestha, Pratikshya Wasti, and Vijay S. GC. 2024. "Nepali Migrant Workers and Their Occupational Health Hazards in the Workplace: A Scoping Review" Sustainability 16, no. 17: 7568. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177568

APA StyleWasti, S. P., Babatunde, E., Bhatta, S., Shrestha, A., Wasti, P., & GC, V. S. (2024). Nepali Migrant Workers and Their Occupational Health Hazards in the Workplace: A Scoping Review. Sustainability, 16(17), 7568. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177568