Sustainable Healthcare in China: Analysis of User Satisfaction, Reuse Intention, and Electronic Word-of-Mouth for Online Health Service Platforms

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2. Perceived Service Quality

2.3. Subjective Knowledge

2.4. Satisfaction, Reuse Intention, and e-WOM

2.5. Moderating Effect of Health Consciousness

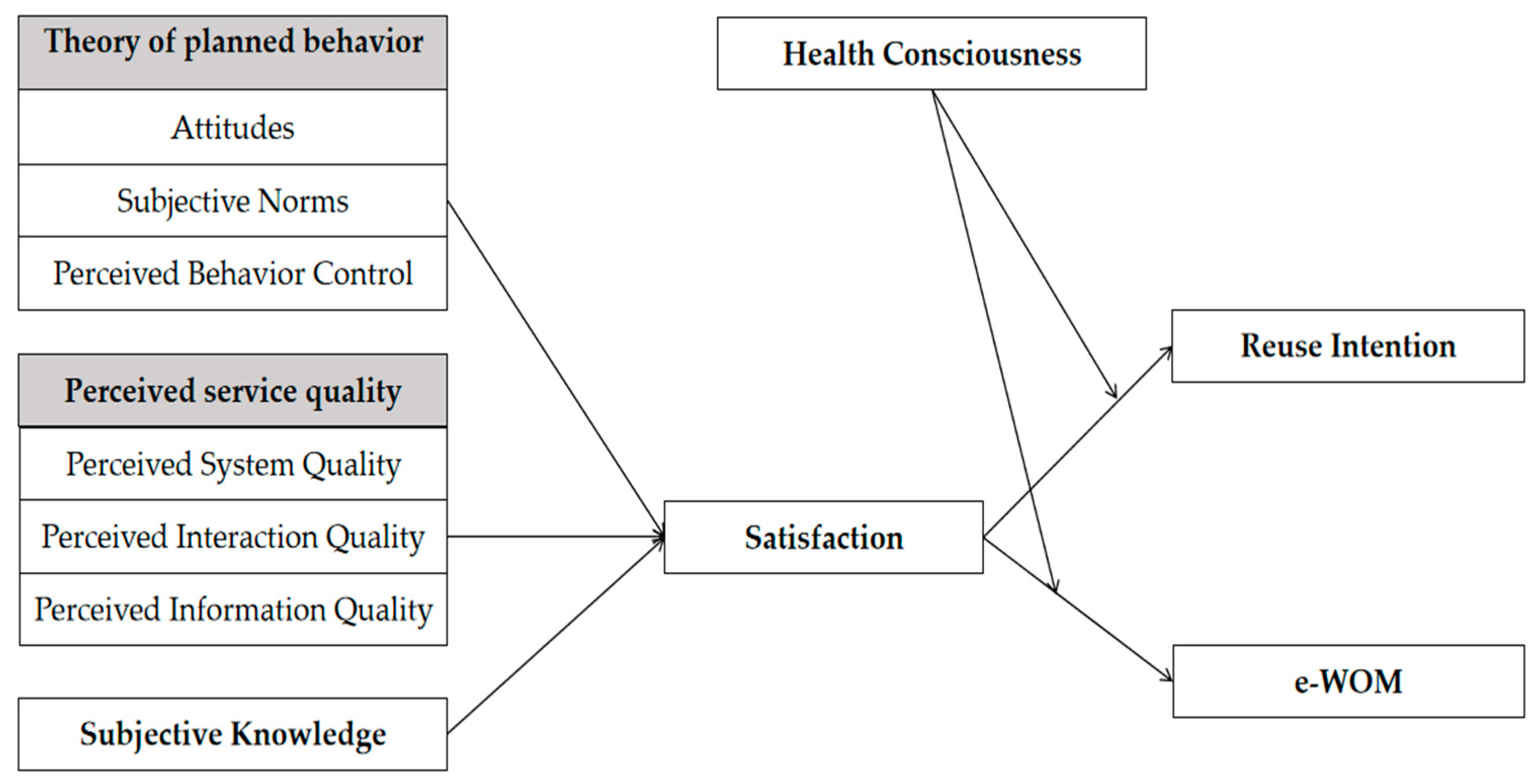

2.6. Research Model

3. Research Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Data Analytic Procedure

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Testing

4.2. Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

4.3. Moderation Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusion

5.1. Summary of Research Results

5.2. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, B.X.; Kjaerulf, F.; Turner, S.; Cohen, L.; Donnelly, P.D.; Muggah, R.; Davis, R.; Realini, A.; Kieselbach, B.; MacGregor, L.S.; et al. Transforming Our World: Implementing the 2030 Agenda Through Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37 (Suppl. S1), 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanobini, P.; Del Riccio, M.; Lorini, C.; Bonaccorsi, G. Empowering Sustainable Healthcare: The Role of Health Literacy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; An, B.; Xu, M.; Gan, D.; Pan, T. Internal or external Word-of-Mouth (WOM), why do patients choose doctors on online medical services (OHSs) single platform in China? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, P.; Liu, L. Factors affecting user intention to pay via online medical service platform: Role of misdiagnosis risk and timeliness of response. Int. J. Healthc. Inf. Syst. Inform. 2022, 16, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. Designing a doctor evaluation index system for an online medical platform based on the information system success model in China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1185036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lee, P.K.C. Improving the effectiveness of online healthcare platforms: An empirical study with multi-period patient–doctor consultation data. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 207, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addotey-Delove, M.; Scott, R.E.; Mars, M. Healthcare Workers’ Perspectives of mHealth Adoption Factors in the Developing World: Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Hu, J.; Liu, D.; Zhou, C. Towards Sustainable Healthcare: Exploring Factors Influencing Use of Mobile Applications for Medical Escort Services. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lu, N. Service provision, pricing, and patient satisfaction in online health communities. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 110, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lv, D.; Li, W.; Xing, Z. Promotion strategy for online healthcare platform during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from spring rain doctor in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 960752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.C.; Zhao, X.; Wu, J. Online physician–patient interaction and patient satisfaction: Empirical study of the Internet hospital service. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e39089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 53rd Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. Available online: https://www.cnnic.cn/n4/2024/0322/c88-10964.html (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Cao, J.; Feng, H.; Lim, Y.; Kodama, K.; Zhang, S. How Social Influence Promotes the Adoption of Mobile Health among Young Adults in China: A Systematic Analysis of Trust, Health Consciousness, and User Experience. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Hoque, M.R.; Jamil, M.A.A. Predictors of users’ preferences for online health services. J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Zhang, M.; Kwok, A.P.K.; Zeng, H.; Li, Y. The roles of trust and its antecedent variables in healthcare consumers’ acceptance of online medical consultation during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.; Khan, S.; Khan, I.U.; Khan, S.U.; Xie, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, G. Assessing the adoption of e-health technology in a developing country: An extension of the UTAUT model. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211027565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Lu, X.; Zhang, X. What drives the adoption of online health communities? An empirical study from patient-centric perspective. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, H.; Park, J. A study on the intention to use Korean telemedicine services: Focusing on the UTAUT2 model. In Data Science and Digital Transformation in the Fourth Industrial Revolution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, A.; Díaz-Martín, A.M.; Yagüe Guillén, M.J. Modifying UTAUT2 for a cross-country comparison of telemedicine adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 130, 107183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.; Chen, S.-C.; Wiangin, U.; Ma, Y.; Ruangkanjanases, A. Customer behavior as an outcome of social media marketing: The role of social media marketing activity and customer experience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.; Costa e Silva, S.; Ferreira, M.B. How convenient is it? Delivering online shopping convenience to enhance customer satisfaction and encourage e-WOM. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkorful, V.E.; Shuliang, Z.; Lugu, B.K.; Jianxun, C. Consumers’ mobile health adoption intention prediction utilizing an extended version of the theory of planned behavior: The moderating role of Internet bandwidth. ACM SIGMIS Database 2022, 53, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-H.; Chiu, C.-M. Predicting electronic service continuance with a decomposed theory of planned behaviour. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2004, 23, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.A.-T.; Biswas, C.; Roy, M.; Akter, S.; Kuri, B.C. The applicability of theory of planned behaviour to predict domestic tourist behavioural intention: The case of Bangladesh. GeoJ. Tour. Geosites 2020, 31, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, N.; Deshmukh, S.G.; Vrat, P. Service quality models: A review. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2005, 22, 913–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaja, R.; Krasniqi, M. Patient satisfaction with quality of care in public hospitals in Albania. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 925681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akter, S.; D’Ambra, J.; Ray, P.; Hani, U. Modelling the impact of mHealth service quality on satisfaction, continuance and quality of life. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2013, 32, 1225–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B. Patient continued use of online health care communities: Web mining of patient–doctor communication. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, J.; Kim, B. The effects of service quality of medical Information O2O Platform on Continuous Use Intention: Case of South Korea. Information 2022, 13, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, B.; Behravesh, E.; Abubakar, A.M.; Kaya, O.S.; Orús, C. The moderating role of Website familiarity in the relationships between E-service quality, e-satisfaction and e-loyalty. J. Internet Commer. 2019, 18, 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieniak, Z.; Aertsens, J.; Verbeke, W. Subjective and objective knowledge as determinants of organic vegetables consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wei, D.; Li, C.; Gao, P.; Ma, R.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, C. How to promote telemedicine patient adoption behavior for greener healthcare? J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsotouhy, M.M.; Ghonim, M.A.; Alasker, T.H.; Khashan, M.A. Investigating health and fitness app users’ stickiness, WOM, and continuance intention using S-O-R Model: The moderating role of health consciousness. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 1235–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 10, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, L.; Tossan, V.; Drennan, J. Consumer acceptance of mHealth services: A comparison of behavioral intention models. Serv. Mark. Q. 2017, 38, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Luximon, Y.; Qin, M.; Geng, P.; Tao, D. The determinants of user acceptance of mobile medical platforms: An investigation integrating the TPB, TAM, and patient-centered factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, W.-T.; Hsieh, P.-J. Understanding the acceptance of health management mobile services: Integrating theory of planned behavior and health belief model. In Posters’ Extended Abstracts, Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Stephanidis, C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Hu, Y.; Pfaff, H.; Wang, L.; Deng, L.; Lu, C.; Xia, S.; Cheng, S.; Zhu, X.; Wu, X. Determinants of patients’ intention to use the online inquiry services provided by Internet hospitals: Empirical evidence from China. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondzie-Micah, V.; Qigui, S.; Arkorful, V.E.; Lugu, B.K.; Bentum-Micah, G.; Ayi-Bonte, A.N.A. Predicting consumer intention to use electronic health service: An empirical structural equation modeling approach. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22, e2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zheng, J.; Liu, R. Factors affecting users’ continuous usage in online health communities: An integrated framework of SCT and TPB. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Quaddus, M. Expectation–confirmation theory in information system research: A review and analysis. In Information Systems Theory: Explaining and Predicting Our Digital Society; Dwivedi, Y.K., Wade, M.R., Schneberger, S.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 441–469. [Google Scholar]

- Birkmeyer, S.; Wirtz, B.W.; Langer, P.F. Determinants of mHealth success: An empirical investigation of the user perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 59, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Du, H. Behavioral intentions of urban rail transit passengers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Tianjin, China: A model integrating the theory of planned behavior and customer satisfaction theory. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 2021, 8793101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcand, M.; PromTep, S.; Brun, I.; Rajaobelina, L. Mobile banking service quality and customer relationships. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 1068–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senić, V.; Marinković, V. Patient care, Satisfaction and service quality in health care. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. Servqual: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer Perc. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, A.; Money, A.H.; Berthon, P.R. Service quality and satisfaction—The moderating role of value. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 1338–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoke, M.; Umoke, P.C.I.; Nwimo, I.O.; Nwalieji, C.A.; Onwe, R.N.; Emmanuel Ifeanyi, N.; Samson Olaoluwa, A. Patients’ satisfaction with quality of care in general hospitals in Ebonyi State, Nigeria, using SERVQUAL theory. SAGE Open Med. 2020, 8, 2050312120945129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitsios, F.; Stefanakakis, S.; Kamariotou, M.; Dermentzoglou, L. Digital service platform and innovation in healthcare: Measuring users’ satisfaction and implications. Electronics 2023, 12, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Malhotra, A.A. E-S-QUAL: A multiple-item scale for assessing electronic service quality. J. Serv. Res. 2005, 7, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamarri, S.; Akter, S.; Ray, P.; Tseng, C.-L. Distinguishing ‘mHealth’ from other healthcare services in a developing country: A study from the service quality perspective. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2014, 34, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandesenda, A.I.; Yana, R.R.; Sukma, E.A.; Yahya, A.; Widharto, P.; Hidayanto, A.N. Sentiment analysis of service quality of online healthcare platform using fast large-margin. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Informatics, Multimedia, Cyber and Information System (ICIMCIS), Jakarta, Indonesia, 19–20 November 2020; Volume 2020, pp. 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Delone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dagger, T.S.; Sweeney, J.C.; Johnson, L.W. A hierarchical model of health service quality: Scale development and investigation of an integrated model. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 10, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Tsai, C.-S.; Hsiung, H.-W.; Chen, K.-Y. Linkage between frontline employee service competence scale and customer perceptions of service quality. J. Serv. Mark. 2015, 29, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbach, N.; Müller, B. The updated DeLone and McLean model of information systems success. In Information Systems Theory: Explaining and Predicting Our Digital Society; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Yin, P.; Deng, Z.; Wang, R. Patient–physician interaction and trust in online health community: The role of perceived usefulness of health information and services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, A.; Ridwandono, D.; Suryanto, T.L.M.; Safitri, E.M.; Khusna, A. Service quality analysis of m-health application satisfaction and continual usage. In Proceedings of the 7th Information Technology International Seminar (ITIS), Surabaya, Indonesia, 6–8 October 2021; IEEE Publications: Piscataway, NJ, USA; Volume 2021, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Oppong, E.; Hinson, R.E.; Adeola, O.; Muritala, O.; Kosiba, J.P. The effect of mobile health service quality on user satisfaction and continual usage. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2021, 32, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keikhosrokiani, P.; Mustaffa, N.; Zakaria, N.; Abdullah, R. Assessment of a medical information system: The mediating role of use and user satisfaction on the success of human interaction with the mobile healthcare system (iHeart). Cogn. Technol. Work 2020, 22, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucks, M. The effects of product class knowledge on information search behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaniaud, N.; Métayer, N.; Megalakaki, O.; Loup-Escande, E. Effect of prior health knowledge on the usability of two home medical devices: Usability study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-I.; Fu, H.-P.; Mendoza, N.; Liu, T.-Y. Determinants impacting user behavior towards emergency use intentions of m-health services in Taiwan. Healthcare 2021, 9, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-M. Influence of informational clues on subjective knowledge, concern, and satisfaction and behavioral intention toward healthy foods in full-service restaurants. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2016, 22, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhahir, A.M.; Alqahtani, J.S.; Althobiani, M.A.; Alghamdi, S.M.; Alanazi, A.F.; Alnaim, N.; Alqarni, A.A.; Alwafi, H. Current knowledge, satisfaction, and use of e-health mobile application (Seha) among the general population of Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A.; Surprenant, C. An investigation into the determinants of customer satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.A.; Sheth, J.N. The Theory of Buyer Behavior; John Willey & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1969; Volume 63, p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.; Chen, J.-L.; Yen, D.C. Theory of planning behavior (TPB) and customer satisfaction in the continued use of e-service: An integrated model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 2804–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, E.; Johnson, M.S. The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison-Walker, L.J. The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 4, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, A.M. The word-of-mouth phenomenon in the social media era. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 56, 631–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruen, T.W.; Osmonbekov, T.; Czaplewski, A.J. eWOM: The impact of customer-to-customer online know-how exchange on customer value and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.K.; Zainol, N.R.; Nawi, N.C.; Patwary, A.K.; Zulkifli, W.F.W.; Haque, M.M. Halal healthcare services: Patients’ satisfaction and word of mouth lesson from Islamic-friendly hospitals. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Jain, H.K.; Liang, C. Understanding the role of mobile Internet-based health services on patient satisfaction and word-of-mouth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellande, S.; Gilly, M.C.; Graham, J.L. Gaining compliance and losing weight: The role of the service provider in health care services. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Hassan, L.M. The role of health consciousness, food safety concern and ethical identity on attitudes and intentions towards organic food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit Kumar, G. Framing a model for green buying behavior of Indian consumers: From the lenses of the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, R.B.; Remar, D.; Parsa, H.G. Health consciousness, menu information, and consumers’ purchase intentions: An empirical investigation. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, W.-M.; Lee, P.K.C.; Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yu, Q. What motivates Chinese young adults to use mHealth? Healthcare 2019, 7, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, N. Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychol. Assess. 1996, 8, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.; Majri, D.Y.; Abdul Rahman, I.K. Covariance based-structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) using AMOS in management research. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 21, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 1989; Volume 210. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings; Pearson Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.K.; Huang, H.-L.; Lai, C.-C. Continuance intention in running apps: The moderating effect of relationship norms. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2022, 23, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Indicators | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 300 | 50.6 |

| Female | 293 | 49.4 | |

| Age | 20–29 | 153 | 25.8 |

| 30–39 | 148 | 25.0 | |

| 40–49 | 145 | 24.4 | |

| Over 50 (including 50 years old) | 147 | 24.8 | |

| Education level | High school or below | 127 | 21.4 |

| University or college graduate | 303 | 51.1 | |

| Postgraduate or above | 163 | 27.5 | |

| Monthly income | Less than 851 USD (excluding 851 USD) | 203 | 34.2 |

| 851 USD–1277 USD (excluding 1277 USD) | 181 | 30.5 | |

| More than 1277 USD | 209 | 35.3 |

| Constructs | Items | Item Source |

|---|---|---|

| Attitudes (ATT) | I think using the OHS platform is a wise idea. | [22,37] |

| I think using the OHS platform is a good idea. | ||

| I think the OHS platform is useful for me. | ||

| Subjective Norms (SN) | My significant others understand my use of OHS platforms. | |

| My significant others are supportive of my use of OHS platforms. | ||

| My significant others think that my using OHS platforms is a good idea. | ||

| My significant others will recommend a good OHS platform to me. | ||

| Perceived Behavior Control (PBC) | I can access the OHS platform whenever I need to. | |

| I can make my own decisions on whether to use the OHS platform. | ||

| Searching for health information using OHS platforms is something that I can do with confidence. | ||

| I do not find using the OHS platform difficult. | ||

| Perceived System Quality (PSQ) | I am provided with the health information I need through the OHS platform whenever needed. | [28,52,55] |

| I am provided with the health information I need through the OHS platform wherever needed. | ||

| It is easy to search for health information using the OHS platform. | ||

| It is convenient to schedule a hospital appointment or receive a health consultation using the OHS platform. | ||

| The OHS platform is run accurately and consistently without errors. | ||

| Perceived Interaction Quality (PITQ) | The OHS platform gives me prompt feedback when I ask about hospital appointments or health-related questions. | |

| The OHS platform understands my specific needs when I ask about hospital appointments or health-related questions. | ||

| The OHS platform responds courteously when I ask about hospital appointments or health-related questions. | ||

| The OHS platform provides me with personal attention in areas such as disease prevention. | ||

| Perceived Information Quality (PIFQ) | Health-related information obtained through the OHS platform is valuable to me. | |

| I can obtain the latest health information using the OHS platform. | ||

| Reviews from other users posted on the OHS platform are useful. | ||

| I can get up-to-date information from the OHS platform since the information is continuously updated. | ||

| Subjective Knowledge (SK) | I know the service characteristics (information on the service provision) of OHS platforms well. | [61] |

| I know how to use OHS platforms well. | ||

| I have substantial knowledge about OHS platforms. | ||

| Satisfaction (SAT) | I am satisfied with the disease prevention and health management process through the OHS platform. | [60] |

| I am satisfied with my decision to use OHS platforms. | ||

| I am satisfied with the overall use of OHS platforms. | ||

| I am satisfied with the overall services provided by OHS platforms. | ||

| I think OHS platforms have more pros than cons. | ||

| Reuse Intention (RI) | I intend to continue using the OHS platform in the future. | [43] |

| I will use the OHS platform frequently. | ||

| I will regularly use the OHS platform, where possible. | ||

| I will gradually increase the frequency of using the OHS platform in the future. | ||

| Electronic Word-of-Mouth (e-WOM) | I am willing to recommend the OHS platform to others. | [77] |

| I will frequently mention the service of OHS platforms to others. | ||

| I will discuss the OHS platform’s good services/positive points with other people online. | ||

| Health Consciousness (HC) | Living a life with the best health I can have is very important to me. | [34] |

| A suitable diet, exercise, and prophylactic treatment will help me stay healthy for my lifetime. | ||

| My health depends on how well I manage it. | ||

| I make active efforts to prevent disease. | ||

| I will do my best to stay healthy. |

| Variable | Items | Standardization Estimate | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | ATT1 | 0.721 | 0.774 | 0.534 | 0.774 |

| ATT2 | 0.734 | ||||

| ATT3 | 0.736 | ||||

| SN | SN1 | 0.744 | 0.845 | 0.578 | 0.846 |

| SN2 | 0.770 | ||||

| SN3 | 0.778 | ||||

| SN4 | 0.749 | ||||

| PBC | PBC1 | 0.732 | 0.831 | 0.555 | 0.833 |

| PBC2 | 0.742 | ||||

| PBC3 | 0.724 | ||||

| PBC4 | 0.779 | ||||

| PSQ | PSQ1 | 0.792 | 0.850 | 0.535 | 0.852 |

| PSQ2 | 0.741 | ||||

| PSQ3 | 0.722 | ||||

| PSQ4 | 0.678 | ||||

| PSQ5 | 0.721 | ||||

| PITQ | PITQ1 | 0.736 | 0.826 | 0.547 | 0.828 |

| PITQ2 | 0.739 | ||||

| PITQ3 | 0.658 | ||||

| PITQ4 | 0.764 | ||||

| PIFQ | PIFQ1 | 0.774 | 0.837 | 0.564 | 0.838 |

| PIFQ2 | 0.758 | ||||

| PIFQ3 | 0.704 | ||||

| PIFQ4 | 0.766 | ||||

| SK | SK1 | 0.773 | 0.791 | 0.565 | 0.795 |

| SK2 | 0.792 | ||||

| SK3 | 0.685 | ||||

| SAT | SAT1 | 0.773 | 0.877 | 0.591 | 0.878 |

| SAT2 | 0.751 | ||||

| SAT3 | 0.802 | ||||

| SAT4 | 0.722 | ||||

| SAT5 | 0.794 | ||||

| RI | RI1 | 0.822 | 0.868 | 0.623 | 0.869 |

| RI2 | 0.779 | ||||

| RI3 | 0.757 | ||||

| RI4 | 0.798 | ||||

| e-WOM | e-WOM1 | 0.837 | 0.828 | 0.619 | 0.829 |

| e-WOM2 | 0.771 | ||||

| e-WOM3 | 0.750 | ||||

| HC | HC1 | 0.794 | 0.864 | 0.564 | 0.866 |

| HC2 | 0.739 | ||||

| HC3 | 0.660 | ||||

| HC4 | 0.742 | ||||

| HC5 | 0.811 |

| ATT | SN | PBC | PSQ | PITQ | PIFQ | SK | SAT | RI | e-WOW | HC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 0.731 | ||||||||||

| SN | 0.119 | 0.760 | |||||||||

| PBC | 0.168 | 0.284 | 0.745 | ||||||||

| PSQ | 0.260 | 0.367 | 0.460 | 0.740 | |||||||

| PITQ | 0.140 | 0.354 | 0.355 | 0.427 | 0.751 | ||||||

| PIFQ | 0.135 | 0.354 | 0.401 | 0.421 | 0.419 | 0.752 | |||||

| SK | 0.186 | 0.216 | 0.490 | 0.501 | 0.350 | 0.360 | 0.752 | ||||

| SAT | 0.365 | 0.392 | 0.573 | 0.607 | 0.578 | 0.613 | 0.577 | 0.769 | |||

| RI | 0.207 | 0.260 | 0.296 | 0.337 | 0.389 | 0.424 | 0.376 | 0.613 | 0.789 | ||

| e-WOW | 0.174 | 0.302 | 0.354 | 0.361 | 0.410 | 0.419 | 0.431 | 0.649 | 0.582 | 0.787 | |

| HC | 0.112 | 0.045 | 0.171 | 0.206 | 0.163 | 0.220 | 0.084 | 0.267 | 0.358 | 0.425 | 0.751 |

| Hypothesis | β | SE | CR | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1-1. ATT → SAT | 0.177 | 0.039 | 4.982 | 0.000 *** |

| H1-2. SN → SAT | 0.055 | 0.038 | 1.507 | 0.132 |

| H1-3. PBC → SAT | 0.157 | 0.039 | 3.758 | 0.000 *** |

| H2-1. PSQ → SAT | 0.136 | 0.040 | 3.097 | 0.002 ** |

| H2-2. PITQ → SAT | 0.234 | 0.041 | 5.743 | 0.000 *** |

| H2-3. PIFQ → SAT | 0.281 | 0.036 | 6.759 | 0.000 *** |

| H3. SK → SAT | 0.211 | 0.035 | 4.811 | 0.000 *** |

| H4-1. SAT → RI | 0.632 | 0.058 | 13.431 | 0.000 *** |

| H4-2. SAT → e-WOW | 0.668 | 0.063 | 14.039 | 0.000 *** |

| Hypothesis | ∆χ2, ∆df | LOW HC (N = 214) | HIGH HC (N = 379) | Conclusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | C.R. | β | C.R. | |||

| H5 SAT → RI | ∆χ2(1) = 2.637 | 0.483 *** | 6.561 | 0.698 *** | 10.191 | Reject |

| H6 SAT → e-WOW | ∆χ2(1) = 6.663 ** | 0.477 *** | 6.258 | 0.787 *** | 11.474 | Accept |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, J.; Ryu, M.H. Sustainable Healthcare in China: Analysis of User Satisfaction, Reuse Intention, and Electronic Word-of-Mouth for Online Health Service Platforms. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7584. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177584

Jin J, Ryu MH. Sustainable Healthcare in China: Analysis of User Satisfaction, Reuse Intention, and Electronic Word-of-Mouth for Online Health Service Platforms. Sustainability. 2024; 16(17):7584. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177584

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Jiexiang, and Mi Hyun Ryu. 2024. "Sustainable Healthcare in China: Analysis of User Satisfaction, Reuse Intention, and Electronic Word-of-Mouth for Online Health Service Platforms" Sustainability 16, no. 17: 7584. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177584

APA StyleJin, J., & Ryu, M. H. (2024). Sustainable Healthcare in China: Analysis of User Satisfaction, Reuse Intention, and Electronic Word-of-Mouth for Online Health Service Platforms. Sustainability, 16(17), 7584. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177584