Abstract

The construction industry faced several challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic, affecting different aspects of construction projects, such as the financial stability of companies and the mental well-being of professionals. However, there is limited knowledge about how these challenges impacted the skills required by professionals in construction. Therefore, the aim of this study is to analyze changes in skills required by construction professionals in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. To do so, we qualitatively analyzed interviews obtained from construction professionals in Chile who worked through the pandemic to study how skills required by construction professionals before the pandemic were impacted during, and after the pandemic. The results indicate that before the pandemic, the most valued skills were related to teamwork, decision-making, planning, and leadership. During the development of the COVID-19 pandemic, skills such as effective communication, computer skills, planning, and stress management were prominent. Regarding the post-pandemic period, interviewees emphasized that construction professionals required mainly adaptability to change, stress management, and planning skills. Our study contributes by identifying changes in the skills required by construction professionals, emphasizing a shift towards skills like digital communication, adaptability, and stress management. Additionally, our study emphasizes planning as the most relevant skill for construction professionals to deal with a highly disruptive event such as the pandemic in construction projects. The study contributed to theorizing the consequences of the pandemic faced by the construction sector in the context of skills required by construction professionals. In practicality, construction managers may use our results to develop strategies to adapt to the post-pandemic context and be prepared for future disruptive events. Ultimately, this will help make the construction industry a more resilient sector.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 pandemic on 11 March 2020, marking a significant shift in human life and economic dynamics [1,2]. This global event caused widespread disruptions and a substantial slowdown in economic growth [3], mainly attributed to government regulations to mitigate the spread of the virus, including mobility restrictions, border closures, and social distancing measures [4]. Such restrictions limited the regular operations of multiple sectors, such as education, health services, manufacturing, and construction. Of note, some sectors were able to adapt and started to operate using teleworking or online services, such as education. However, sectors such as manufacturing, health, and construction were limited due to the required presence of people working in the field.

In Chile, where this study was developed, the government and various sectors responded to the pandemic with similar strategies to those implemented worldwide [5]. For example, the “step-by-step plan” was announced in July 2020 to stop the spread of the virus [6]. The plan consisted of five steps: quarantine, transition, preparation, initial opening, and advanced opening. Each step had specific measures for containment, mobility, permitted activities, and gauging [7]. Similarly, this plan was implemented in the workplace, adopting a set of preventive measures for both employers and workers [6]. Additionally, in the context of the construction industry, the Chilean Chamber of Construction developed a “health protocol for construction projects” that established guidelines to protect the health of workers and their families [8].

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the construction industry in multiple ways [9,10,11]. Quarantines, mobility restrictions, and the interruption of global production and supply chains posed various challenges to construction professionals [12,13], such as contractual problems, force majeure clauses [14], project delays [11,15], and project suspensions [16,17]. As a result, there were material and equipment shortages, price increases, and delivery delays [16,18,19,20]. Construction companies had to adopt new technological and methodological tools to support the management of different phases of construction projects throughout their lifecycle [21,22]. They also had to implement rigorous protocols to minimize risks and ensure the health and safety of their workers [23,24,25,26,27,28].

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the implementation of strict safety measures at construction sites to ensure the safety of workers and professionals. However, these measures reduced labor efficiency and productivity in general [10,24,29]. This was mainly due to the decrease in on-site personnel, limited availability of skilled workers, shorter working hours, and project suspensions due to non-compliance with regulations [17,23,30]. As a result, project schedules and costs were disrupted [31]. On a personal level, COVID-19 caused multiple mental health challenges for professionals. For instance, un-certainty about their health, fear of transmitting the virus to their families, job insecurity, and the need to adjust to new working methodologies [32,33]. These issues, combined with an insecure work environment, concerns about job stability, increased workload, and inexperience with digital tools and communication methods, resulted in anxiety, stress, and depression among construction professionals [34].

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic led construction professionals to adjust to new and never-seen working conditions to ensure that projects could be executed successfully [9]. These adjustments meant that construction professionals had to update existing skills and/or simply develop new skills to meet the changing requirements to work through the pandemic [26,35]. In some cases, new technologies and methodologies were introduced [36], which required professionals to undergo training programs and acquire new skills. These new approaches improved traditional construction processes [37,38], increasing the adoption of innovative methodologies even after the pandemic had finished.

Understanding changes in the means and methods of construction projects during the pandemic and the corresponding skills required by construction professionals is important for the post-pandemic context of the construction industry. Understanding new or updated skills required by construction professionals is also important for selection and recruitment processes in construction companies.

Despite extensive debate about how the COVID-19 pandemic transformed the construction industry, there is a research gap on how the pandemic disrupted skills required by construction professionals to perform in construction projects. The pandemic disrupted operations and protocols and demanded a redefinition of professional skills for construction professionals. This research gap leads us to the question of how skills required by construction professionals were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Ultimately, to provide a response to this question this research aims to analyze how the skills required by construction professionals in construction were impacted by the pandemic by comparing skills valued before, during, and after the pandemic. To do so, a qualitative content analysis of interviews is performed with professionals with experience in construction and who worked through the pandemic.

2. Literature Background

2.1. Challenges of COVID-19 for Construction Professionals

The COVID-19 pandemic placed numerous challenges for construction professionals managing construction projects as discussed by Sami Ur Rehman et al. [16], Alsharef et al. [19], and Assaad and El-Adaway [18]. These authors agree that construction projects faced significant challenges such as material shortages, schedule delays, health and safety issues, cash flow disruptions, delayed permits and approvals, reduced productivity, and contractual matters. Ogunnusi et al. [39] also highlight some challenges related to workflow disruption, emerging political issues, worker anxiety, and COVID-19 revisions versus force majeure in construction contracts. Sierra [40] identified critical challenges faced by contractors, such as economic costs, legal and contractual exposures, labor availability, and un-certainty regarding pandemic progression. Similarly, Araya et al. [41] and Esa et al. [20], studying projects in Chile and Malaysia, respectively, concluded that the most common challenges faced included work stoppage or delays, financial complications due to increased project costs, and declines in productivity. Al-Mahdawi [42] stresses that the pandemic disrupted 16 essential factors, with safety and risk management being the most adversely affected. Ayat and Kang [4] also systematically investigated the pandemic’s effects on the construction industry. Their findings indicated that research in this field primarily focuses on various areas, such as challenges and risks, health and safety, future developments, technological adaptability, contractual issues, modifications in labor processes, and the implementation of protective measures.

Implementing safety measures in the workplace was a challenge for construction professionals. Amoah and Simpeh [23] identified critical elements that contributed to an un-safe work environment in the South African industry, such as a shortage of personal protective supplies, difficulties sharing tools and equipment, and poor disinfection. Studies by Avice [43] in the United States and Moreno et al. [44] in Spain highlight the importance of constant communication and education of workers, reorganizing work sequences, and establishing a culture of responsibility to ensure compliance with safety regulations on construction sites. Other studies focus on workers’ mental health challenges and adaptability to new work methods. Nguyen et al. [45], Pamidimukkala and Kermanshachi [34], and Asis [32] indicate that factors such as un-certainty about their health status, fear of contagion for their families, a perceived insecure work environment, concerns about job stability, and excessive workloads caused anxiety, stress, and depression among professionals and workers. Asaad et al. [46] and Leontie et al. [47] highlight challenges posed by the accelerated adoption of emerging technologies and intensifying digitization in communications and sectoral information during the pandemic.

In summary, recent research has shown that the pandemic presented a wide range of challenges to professionals in the construction industry. These findings emphasize the need to study the skills required for these professionals to adapt to the adverse environments caused by COVID-19 in the construction sector.

2.2. Studies Related to the Skills of Construction Professionals

Effective collaboration among professionals with diverse expertise is crucial for successful construction projects [48]. As such, construction professionals must possess multiple skills to facilitate effective interaction between specialists involved in construction projects. International studies have highlighted the importance of these skills and their direct impact on achieving successful construction projects. In the United States, existing literature has identified the most valued skills by consulting different groups of industry professionals. Ahn et al. [49] classified key skills into four categories: general (communication skills and environmental awareness), effective (leadership, collaboration, and interpersonal), cognitive (ethics, problem-solving, and adaptability), and technical (technical, practical, computer, and estimating skills).

Similarly, Farooqui and Ahmed [50] surveyed professionals in South Florida to understand perceptions of essential skills for construction graduates, classifying them into five areas: personal and professional attributes, technical, managerial, industrial, and business, interpersonal, and legal competencies. They concluded that health and safety knowledge and interpretation of contract documents are the most critical skills. Finally, Bhattacharjee et al. [51] conducted surveys of construction industry representatives in the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest regions of the United States to understand industry and student expectations of the skills needed for career success. Both employers and students highlighted the importance of confidence, honesty, construction document interpretation, and problem-solving.

Several studies have adopted different methodologies to explore the skills needed by construction professionals. Gao and Eldin [52] analyzed over 20,000 job postings in the construction industry using advanced data mining techniques. They found that teamwork and communication skills, a university degree, and computer skills were the most valued requirements for these positions. In contrast, Wiezel and Badger [53] collected data during a project management training seminar using an innovative approach based on games and reflective exercises. They concluded that successful construction professionals require 14 essential skills, which can be classified into four areas: technical/virtual, management, cognitive, and leadership. In Canada, Arain [54] identified 17 key competencies to improve the employability of young professionals in the sector based on various research and industry perspectives. Among the most essential skills, he highlighted construction vision, project management, leadership, business skills, professionalism, and communication skills. Similarly, Baharudin [55] stressed the importance of understanding engineering drawings, written and oral communication, and leadership skills.

Studies conducted in the South African context converge on problem-solving as the most valued and demanded skill by professionals in the sector. Aliu and Aigbavboa [56] emphasize the importance of communication, computer skills, critical thinking, and teamwork for employability in the industry. On the other hand, Smallwood [57] identifies additional skills such as administration, oral communication, coordination, decision-making, leadership, and planning among the ten most relevant. Employers’ satisfaction with the skills of recent graduates was explored by Davies et al. [58] and Aliu and Aigbavboa [59]. Davies et al. [58] found little difference between employer and graduate perceptions in 16 of the 22 skills assessed. However, employers rated skills such as listening, teamwork, and creativity more highly, while graduates perceived themselves as better equipped in practical knowledge, problem-solving, and autonomy. In contrast, Aliu and Aigbavboa [59] reported in their study in Nigeria that employers were satisfied with graduates’ academic performance, willingness to learn, and ability to achieve positive results.

The findings of a Delphi study conducted by Nuwan et al. [60] reveal that 12 experts and 44 industry professionals identified several essential skills for construction managers, such as time management, problem-solving, planning, and decision-making. Meanwhile, Simmons et al. [61] highlight the importance of leadership competencies in the industry. They identified 24 key skills: communication, ethics, professionalism, critical thinking, problem-solving, and global perspective. Similarly, decision-making has been identified as a crucial skill in the construction field by several studies, including Odusami [62], van Heerden et al. [63], and Egbu [64]. Odusami’s [62] survey of clients, consultants, and contractors revealed that decision-making, communication, and planning are the most critical skills, according to clients. In contrast, consultants emphasize leadership, motivation, and decision-making. Contractors, on the other hand, stress the importance of communication, decision-making, and planning. Van Heerden et al. [63] found that the construction sector requires a mix of soft skills, including integrity, work ethic, teamwork, responsibility, problem-solving, communication, workplace professionalism, and leadership. However, some differences exist between the currently observed soft skills and those needed. On the other hand, Egbu [64] emphasizes that leadership, communication, motivation, health safety, forecasting, and planning competencies are essential for effective management in the construction field.

Existing literature indicates that achieving excellence in the construction industry requires a variety of skills. Professionals in this field must possess technical and cognitive competencies and interpersonal and managerial skills to succeed. Moreover, soft skills like effective communication, leadership, and problem-solving are essential for their performance and employability.

In summary, existing literature has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic represented a large disruption in the performance of construction projects. Given this context, a research gap that exists in the literature is related to the impacts of the pandemic on the skills required by construction professionals.

3. Methods

This study focuses on analyzing how the skills required by construction professionals were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., during and after) in Chile. Given the limited studies found in the literature on this topic, the authors decided to use an exploratory approach to develop this research. To do so, learning from the experience of construction professionals working during the pandemic was fundamental to leveraging their experiences and knowledge acquired during the pandemic. Therefore, this research was based on a qualitative approach involving three main stages: (1) identification of skills required by construction professionals discussed in the existing literature, (2) interviews with construction professionals, and (3) qualitative analysis of interviews.

Stage 1 involved identifying skills required by construction professionals discussed in the literature in a pre-pandemic context. Given the limited literature, we used skills recognized as relevant in a pre-pandemic context as the starting point for this study. Stage 2 aims to leverage the knowledge and experiences provided by interviewees. Ultimately, Stage 3, through qualitative content analysis, allows the authors to conceptualize the emerging concepts from the interviews.

The purpose of this study is not to claim that our results will be representative of the entire sector of Chile. However, instead of revealing and providing understanding about a subject that has been heavily understudied in the literature, especially in developing nations in Latin America, such as Chile.

3.1. Identification of Skills of Construction Professionals in Literature

The importance of skills for construction professionals has been the subject of previous research, and this study aims to identify the main skills required by professionals in this sector. To achieve this, a literature review was developed following five fundamental stages as proposed by Herrera et al. [65], Briner and Denyer [66], and Damen et al. [67]. These stages included formulating the research question, searching for relevant studies, selecting documents, collecting evidence, and synthesizing the results. The research question guiding this review was “What are the main skills required of construction professionals?”. A specific search equation was designed to answer this question, which was [(construction OR building) AND (professional OR designers OR constructors OR consultants) AND (skill OR competence)]. This equation was applied to the Scopus and Web of Science search engines, resulting in an initial sample of 425 documents. This search was performed between March and August of 2023.

The selection of documents was based on two inclusion criteria: (1) the document must address the topic of human resource skills in construction projects, and (2) the document must report specific skills of construction professionals. Two researchers evaluated the papers using a table in Microsoft Excel 2019 with two columns corresponding to these criteria. The first criterion reduced the sample to 95 documents, and the second criterion ended up selecting 15 relevant documents. A detailed review of these 15 documents identified a total of 39 essential skills for professionals in the construction industry.

3.2. Data Collection: Interviews with Construction Professionals

The interviews with professionals in the construction industry were conducted in two sections. The first section focused on first getting approval and consent from the interviewees to perform and record the interviews and to know the interviewees and their backgrounds, including their profession, years of experience in the industry, and current positions. The second section aimed to identify the main skills for construction performance that interviewees considered crucial before the pandemic. Additionally, it explored which of these skills were strengthened or modified during the pandemic and which were still relevant in a post-COVID-19 context. Data were collected through 15 semi-structured interviews with construction professionals, including architects, civil engineers, and builders, who worked on construction projects before and during the pandemic. Given the emerging nature of the pandemic and the limited information available in the literature about the changes in skills’ requirements for construction professionals due to the pandemic, the study adopted an exploratory approach. A qualitative analysis of the data collected was conducted to understand the impact on professional skills during the pandemic by identifying emerging topics leveraged by interviewees’ experiences during the pandemic. Convenience sampling was used to select participants, choosing individuals based on their experience in construction before and during the pandemic (i.e., working in construction during the pandemic), as well as availability and accessibility.

Additionally, snowball sampling was used, where interviewees provided referrals to other potential participants. The selection criteria for interviewees were twofold: having previous experience in the construction industry and having participated in projects during the pandemic. The interviewees’ experience ranged from 4 to 38 years, averaging 14.8 years. The sampling size used in this study was within the range of the sample sizes used in prior research on the impact of COVID-19 in the construction sector (e.g., n = 5 [68]; n = 19 [9]). Qualitative approaches similar to those used in this study have also been reported in the literature (e.g., [16,32,69]). Participants in interviews were selected until the saturation point was reached, defined as the point where further interviews did not provide significant new information. Existing literature suggests that this point is usually reached after roughly 12 interviews [70]. In the case of this study, the saturation point was reached with 15 interviews. Table 1 supplements this information, detailing the profession, current position, area of expertise, and gender of each interviewee.

Table 1.

Profile of construction professionals interviewed.

The professionals were primarily contacted via email, and the interviews were conducted remotely using platforms, such as Google Meet and Zoom. The interviews took place between November 2022 and February 2023, lasting between 20 and 45 min. The professionals were introduced to the topic of the study, briefed on the research objectives, and assured of their anonymity. The interview questions, which can be found in detail in Appendix A, were designed to meet the study’s primary objective: to analyze how the skills required for construction professionals have evolved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Open-ended questions were utilized to encourage discussion and gather a deeper perspective on the interviewees’ experiences and opinions during the pandemic. Questions about the construction skills before, during, and after the pandemic include:

- Before the arrival of the pandemic, what would you consider to be the skills required for a professional to perform well in the construction industry? (Indicate at least ten skills).

- Once the pandemic started, indicate which skills for the performance of a construction professional were enhanced.

- How and why do you think this occurred among the skills that were enhanced?

- In a post-pandemic context, what skills do you consider necessary for a construction professional’s good performance?

3.3. Qualitative Analysis of Interviews

Once all the interviews are completed, they are transcribed into text, which is the input for the qualitative content analysis. The analysis of interviews in this study was conducted using a qualitative approach, which is exploratory and helps to delve deeper into the context of the problem under study. Due to the constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, several authors have suggested the use of qualitative methods to further understand the impacts of the pandemic in the construction sector (e.g., [5,17,23]). These methods offer greater flexibility, which is essential for understanding emerging themes and fully leveraging the knowledge and experience of the interviewees. Qualitative methods fit very well with problems that are new and need to be conceptualized. Given the limited literature available regarding how the construction industry may deal with a pandemic context, qualitative methods represent an excellent alternative to explore and understand how the skills required by construction professionals may be impacted by the pandemic.

Therefore, a qualitative methodology is a particularly effective tool for investigating the evolution of skills required by construction professionals due to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. This approach enables us to capture and analyze the perceptions and experiences of the participants in-depth, providing valuable insights into how the pandemic has influenced and transformed the skills needed by professionals in this construction sector.

Thematic analysis was used to examine interview responses and identify skills required by construction professionals. Thematic analysis is a rigorous and systematic method that helps identify, analyze, and report patterns (i.e., themes) within the data (i.e., transcripts with the responses from the interviews). This method can be applied to various qualitative data sources, such as interviews, documents, focus group transcripts, and other information sources. The process of thematic analysis includes several key steps [71,72]. Firstly, data preparation and familiarization involve a detailed immersion in the collected material to understand its depth and complexity. Secondly, coding is where labels are assigned to text segments to describe the content concisely. The codes are then grouped to form potential themes, which are meaningful patterns in the data that relate to the research question. Finally, the analysis and presentation of the results occur at a stage in which the meaning of the identified themes is interpreted and communicated coherently and logically in the research report. This method provides a thorough and systematic exploration of the interviewees’ perspectives on the skills required in the construction sector before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The analysis of the interviews began by getting familiar with and preparing the data. Afterward, all the interviews were fully transcribed. The next step was open coding, which involved identifying and labeling emerging themes and patterns in the participants’ responses (i.e., skills). The data was broken down into meaningful units during this phase, and descriptive codes were assigned to the identified skills. The individual codes were organized into broader categories in the code grouping and theme generation phases. These categories were developed inductively from the data to establish relationships among the various codes. The skills identified were grouped into four main categories: Interpersonal Skills, Leadership Skills, Technical and Analytical Skills, and Individual Skills. These categories emerged from both the literature review and the interviewees’ responses. Then, the results were presented by evaluating the themes in-depth to thoroughly understand the data and present the findings coherently. The study also includes a coding dictionary in Appendix B and Appendix C, detailing the categories’ respective definitions and the skills assigned to each category. This provides a clear and organized view of the results obtained during the coding process. Ultimately, applying the coding dictionary to the existing transcripts is performed to obtain the frequency with which skills were identified by interviewees. The counting of the frequencies was performed using a software named QDA Miner 3.0, which is an open software to perform qualitative content analysis. It is important to note that although the counting of frequencies was performed by the software, the identification of categories and creation of the coding dictionary were performed by the researchers.

4. Results

4.1. Construction Professionals’ Skills

The systematic literature review conducted in this study revealed an initial set of 39 essential skills for construction professionals. However, during interviews with construction professionals, a notable finding emerged. One interviewee emphasized the importance of including empathy (S5) as a critical skill. Thus, the list of essential skills was expanded to 40 and is detailed in Table 2. These skills were categorized into four main groups for ease of understanding and analysis: (1) Interpersonal Skills, which include skills such as effective communication (S1) and empathy (S5); (2) Leadership Skills, which encompass aspects such as team management (S17) and decision-making (S18); (3) Technical and Analytical Skills, which comprise industry-specific knowledge and analytical skills such as time management (S24) and cost management (S25); and (4) Individual Skills, which encompass attributes such as adaptability to change (S30) and willingness to learn (S31). Including such a diverse range of skills highlights the complexity and multidimensionality of the skills required in the construction sector. This is especially evident in the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2.

Skills of construction professionals.

4.2. Construction Professionals’ Skills and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Table 3 provides the frequencies of coding for each skill identified for construction professionals during the qualitative analysis. The analysis considers the periods before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. It offers a comprehensive view of the evolution of skills required in this sector in response to the global health crisis. The data is organized into four categories: Interpersonal, Leadership, Technical and Analytical, and Individual Skills. This categorization reflects significant changes in the competencies demanded at different stages of the pandemic.

Table 3.

Skills of construction professionals that existed before and were impacted during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Effective communication (S1) emerged as a critical skill within the Interpersonal Skills category, increasing in importance from being mentioned in 40.0% of the interviews before the pandemic to 73.3% during it. Regarding Leadership Skills, planning (S13) was identified as a crucial competence, mentioned in 66.7% of the interviews before the pandemic and 26.7% during it. Technical and Analytical Skills, particularly computer skills (S19), gained relevance, being mentioned in 73.3% of the interviews during the pandemic. In the category of Individual Skills, adaptability to change (S30) and stress management (S36) were identified as essential, with significant increases in their mention during the pandemic (60.0% and 66.7%, respectively). These skills were good judgment (S38), interpretation of contractual documents (S39), and quality management (S40).

5. Discussions

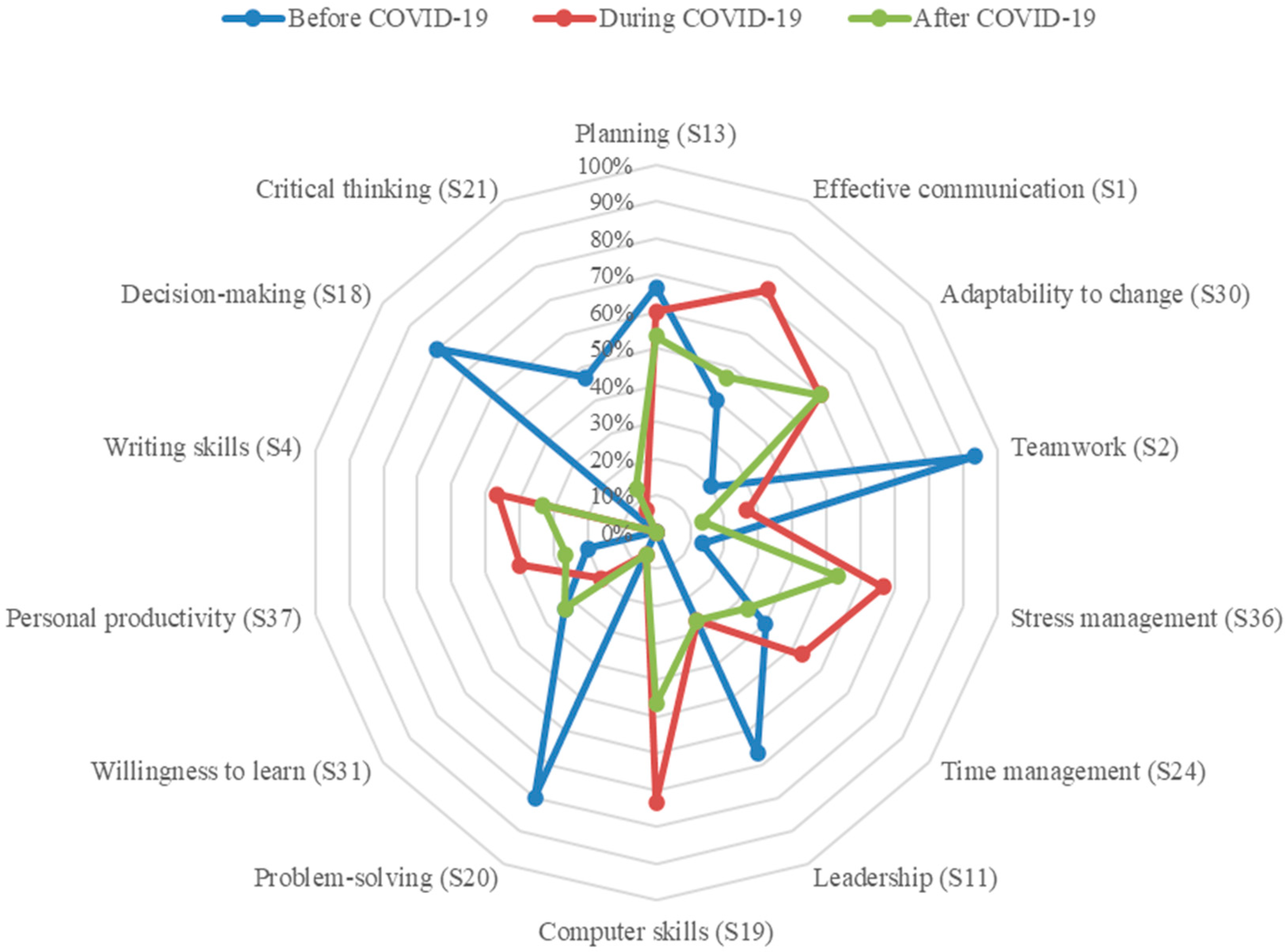

Figure 1 compares the evolution of the 14 skills most frequently mentioned to be required by construction professionals in the interviews, covering the three different stages of the pandemic: before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. It is worth noting the changes in the skills required for professionals in the construction industry in Chile. These changes are discussed in detail in Section 5.1, Section 5.2, Section 5.3 and Section 5.4 and are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Changes in the most frequently mentioned skills required by construction professionals before, during, and after the pandemic.

5.1. Pre-Pandemic Period

Analysis of interview data from the pre-pandemic period highlights the relevance of five essential skills according to construction professionals (see Figure 1). Teamwork (S2) received 14 mentions, followed by decision-making (S18) and problem-solving (S20), each with 12 statements, ranking second. Leadership (S11) and planning (S13) were also highly valued and shared third place in preference. Critical thinking (S21), responsibility (S29), effective communication (S1), time management (S24), and organization (S23) were among the top ten relevant skills. However, interviewees did not mention some skills, such as creativity (S22), computer skills (S19), and flexibility (S32). Notably, the most frequently mentioned skills align with those identified in the existing literature, reinforcing the importance of these skills for professionals in the construction sector. These findings agree with the results of Ahn et al. [49], Bhattacharjee et al. [51], Gao and Eldin [52], Smallwood [57], Nuwan et al. [60], and van Heerden [63].

Teamwork (S2) skills have been identified as critical in construction, reflecting the importance of effective collaboration and coordination between different teams. Although this competency is frequently mentioned in specialized literature, it is not usually ranked as the most important one. Authors such as Gao and Eldin [52] and Bhattacharjee et al. [51] place teamwork (S2) in second and third place, respectively, in their studies. In addition, decision-making (S18) and problem-solving (S20) skills are recognized as fundamental in an environment characterized by un-foreseen situations and technical challenges that require agile and effective responses. In the construction industry, professionals must be able to evaluate multiple options, consider complex factors, and promptly make informed decisions. These skills are widely recognized in relevant studies; for example, Nuwan et al. [60] and Smallwood [57] include them among the research’s five most important competencies. This approach reflects the increasing demand for management and problem-solving skills in the construction industry, especially in dynamic and challenging contexts.

According to our study, leadership (S11) and planning (S13) skills are crucial in the construction industry. Leaders in this sector have significant roles in managing and coordinating teams, as well as in efficiently managing resources and making strategic decisions. Effective planning is also essential to ensuring the smooth and efficient execution of projects, optimizing resources, and reducing associated risks. The importance of leadership and planning is supported by existing literature. Studies by authors like Baharudin [55] and Egbu [64] emphasize these competencies as critical to success in construction management roles. Both leadership and planning provide clear direction, purpose, and focus on projects, which are essential elements for success in the complex and challenging environment of the construction industry.

In summary, before the pandemic, skills related to working in teams and how to make decisions and manage resources in construction projects were highly valued by interviewees among construction professionals.

5.2. Pandemic Period

The aim of analyzing the data collected during the pandemic period was to identify the skills that became more important in the construction industry in Chile, according to the professionals consulted. The findings, detailed in Figure 1 and Table 3, show that specific skills gained more significance during this period. Effective communication (S1) became crucial in the construction industry during the pandemic. Although it was already one of the top ten most important skills before the pandemic, its relevance increased significantly, making it the most relevant skill. Professionals in the industry stress the importance of adapting to different media and platforms to avoid misunderstandings and ensure project success during the pandemic. Of interest, the pandemic placed multiple challenges for construction professionals, one of which was communication in projects. Pre-pandemic communication among construction professionals was performed mainly in person, but with the arrival of the pandemic, communication had to transition to virtual environments, and as such, creating more challenges for some interactions among construction professionals. Probably that is why effective communication was one of the most frequently valued skills during the pandemic.

Additionally, computer skills (S19) have also become more valuable since the pandemic. While previous research emphasized their importance for construction professionals (e.g., Smallwood [57], Wiezel and Badger [53], Simmons et al. [61]), they were not among the most prominent skills required by the construction industry. However, with the transition to virtual environments during the pandemic, studies during the pandemic have shown a rapid adaptation to new technologies and an increase in the digitization of construction processes [11,46,47]. The frequency with which computer skills (S19) were mentioned in interviews may be directly related to mobility constraints and the need to move construction operations to virtual environments. Remote work and virtual collaboration have become indispensable elements in the continuity and success of construction projects. Interviewees emphasized that technology and online collaboration tools were crucial to maintaining smooth communication and effective collaboration between teams, even in challenging circumstances.

Stress management (S36) skills were the second most frequently reported, demonstrating a significant increase from the pre-pandemic period (see Table 3). This change can be attributed to initial health measures and economic challenges, which created un-certainty and constant changes in the construction work environment. Participants expressed additional emotional concerns, such as fear of job loss and increased workload, which added to their own anxiety and their families’ health. These observations are consistent with previous studies (e.g., Asis [32], Nguyen [45], and Pamidimukkala and Kermanshachi [34]) on the emotional and psychological challenges faced by construction professionals during the pandemic. Of note, the pandemic seems to have increased awareness among professionals of the need to manage stress from workers at construction sites. Perhaps, as the pandemic affected basically everyone around the globe, its challenges were also recognized and faced by most construction professionals.

In third place were adaptability to change (S30) and planning (S13) skills (see Table 3). The increase in their value seems to be linked to multiple factors. The interruption and delay of projects due to imposed restrictions needed a reorganization of dates, schedule adjustments, and established plans. Un-certainty about the duration of these restrictions and the possibility of new limitations created an un-predictable environment, challenging long-term planning and requiring constant adaptation to changing conditions. Finally, incorporating new technologies and digital tools forced professionals to adapt to innovative working and communicating methods during the pandemic.

It is interesting to note that the results show that the frequency of four skills highly increased during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period. These four skills are time management (S17), writing skills (S4), personal productivity (S37), and creativity (S22). This increase appears to be directly related to the significant changes in work routines and conditions during the pandemic. Respondents noted that time management and personal productivity became essential skills to adapt to new at-home or isolated work environments, flexible schedules, and the distractions of working at home during the pandemic. Similarly, writing skills and creativity became more critical due to adjusting to new communication formats. Although writing skills were already used in construction before COVID, the pandemic required enhancing and improving their use to seek innovative approaches to deliver messages effectively. With the increase in remote work during the early months of the pandemic and the reduction in direct supervision, all these skills demanded a high degree of self-discipline. They were critical in setting priorities and schedules, maintaining motivation and focus, and devoting time and effort to improving and developing the quality of work.

5.3. Post-Pandemic Period

Analysis of post-pandemic results suggests continuity in relevant skills, albeit with a slightly altered priority order (see Figure 1). The interviewees emphasized that adaptability to change (S30) is essential in response to a pandemic and is crucial for dealing with disrupting contexts that involve changes, such as incorporating new technologies, innovative construction methods, and fluctuating market demands [73]. This adaptability is considered an essential skill for maintaining efficiency and competitiveness for construction professionals in the construction industry. Furthermore, interviewees stressed that developing this skill is necessary to survive in an ever-changing environment and take advantage of the opportunities that arise from such changes [74]. Hence, adaptability to change reflects the ability to respond to immediate challenges and a proactive approach to anticipate and lead industry transformations. This approach to adaptability highlights an industry-level dynamic that values resilience and innovation, emphasizing the importance of a flexible and forward-thinking mindset in the post-pandemic era [75]. Of note, these results illustrate an opportunity for the construction industry during a post-pandemic environment to push for changes and updates in an industry that has always been characterized as slow to adopt changes and improve productivity and efficiency.

Stress management (S36) has been identified as the second most frequently mentioned skill. Interviewees emphasized the importance of developing this competency for mental and physical health, as discussed in the existing literature [76]. They recognize that maintaining a work-life balance is essential for construction workers. These findings highlight the need to implement effective stress management strategies in work settings [77]. Investing in training on relaxation techniques, mindfulness, and resilience can have a significant impact not only on employee well-being but also on overall productivity at construction projects. Of note, the authors believe that the pandemic may have contributed to improving awareness of stress management and work-life balance concepts among construction professionals. It is important for the construction sector to capitalize on this notion so the quality of life of construction professionals may improve. In doing so, the construction sector may become more attractive for young professionals to develop a career in this field and potentially solve some of the limited workforce problems related to the construction industry.

Additionally, planning is also a crucial skill in the construction industry. The data suggests that regardless of the context (i.e., before, during, or after the pandemic), planning remains essential for construction professionals. Interviewees noted that, with the increase in demand for construction projects, effective planning became even more critical. It is not only about coordinating activities and meeting deadlines, but also about optimizing resources and efficiency in project execution. Meticulous planning is, therefore, a fundamental skill for the success of projects, facilitating the management of un-foreseen challenges and adaptation to dynamic changes in the industry [78].

Effective communication (S1) and computer skills (S19) tied for third place in frequency. Respondents emphasized that it is crucial to develop the ability to communicate effectively regardless of the medium used in a post-pandemic period [79]. Effective communication is essential for promoting team collaboration, streamlining decision-making processes, and ensuring transparent and fluid communication, all of which are crucial elements in the construction industry [80]. Parallel to this, computer skills, including proficiency in project management software, design tools, and cloud-based collaboration systems, are essential for boosting productivity, efficiency, and competitiveness in the sector [81]. Professionals proficient in these technological areas can respond with greater agility to contemporary challenges and take advantage of opportunities arising from the increasing digitization of the construction industry [82]. Therefore, in the post-pandemic context of the construction industry, professionals are strongly advised to focus on developing these specific skills. Strengthening key skills prepares individuals to meet the challenges of a changing environment and contributes significantly to the growth and sustained success of construction companies.

5.4. Main Findings and Contributions

During the three periods examined (i.e., before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic), construction professionals evidenced a shift in the essential skills required by professionals to perform in construction projects. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, traditional skills such as teamwork (S2), leadership (S11), and decision-making (S18) were the most important skills, according to the literature and interviewees. However, once the pandemic began, and its corresponding challenges began, there was a significant change in the skills valued to perform in construction projects, with skills such as effective communication (S1), computer skills (S19), and stress management (S36) becoming more relevant. These skills reflect the professionals’ adaptation to the unique challenges placed by the pandemic on the construction sector, such as working from home, communication challenges, the implementation of new technologies, and large un-certainty about the future. In the post-pandemic context, there has been a persistence in the relevance of the skills highlighted during the pandemic, albeit with some variations in their ranking. For instance, while computer skills remain essential, they have slightly decreased in relevance. Furthermore, adaptability to change (S30) has risen in the ranking, being perceived as a key skill in the stage of post-pandemic recovery for the construction sector.

The study’s findings indicate that planning (S13) is one of the top five skills required in all stages (i.e., before, during, or after a pandemic). This result emphasizes its critical role in professional effectiveness, independent of the stage of the pandemic. Before the pandemic, planning was essential in setting clear goals, allocating resources efficiently, organizing tasks, ensuring effective team coordination, and meeting deadlines. During the pandemic, planning took on a new dimension as it allowed the reorganization of activities, the implementation of safety protocols, and the adaptation of work methodologies to the pandemic context. These actions were vital in maintaining project continuity and reducing the adverse impacts of the health crisis. In the post-pandemic scenario, adequate planning will be crucial in anticipating challenges, identifying opportunities, and optimizing efficiency in construction projects.

Ultimately, results from this study contribute to theory and practice. Our contribution to the literature is related to a better understanding of how the skills required by construction professionals to perform in construction projects were impacted due to the COVID-19 pandemic, namely, in the context of the Chilean construction. These findings contribute to conceptualizing how events such as pandemics may impact the skills required by professionals in the construction sector. Additionally, our results illustrated how construction professionals responded and adapted their skills to the different challenges faced during the pandemic in the construction sector. In practicality, our results can be used by construction managers and companies as input for future recruitment and selection processes and talent management in construction companies in the current post-pandemic context. Moreover, our results contribute to knowing which skills from professionals in construction might be of relevance in future pandemics.

5.5. Limitations and Recommendations

It is important to recognize that certain limitations are inherent in this study. Firstly, the focus is solely on the construction industry in Chile, which makes it difficult to generalize the results to other nations. This limitation stems from the fact that different countries may have varied dynamics and challenges regarding how the construction industry handled the response to the pandemic and the skills required by construction professionals. Nonetheless, this study provides a baseline for studies to be developed in other comparable countries. For instance, these results can be compared with other nations from the South American region that are culturally similar to the case of Chile or developing nations in other regions of the world. Secondly, the study only considers the opinions of construction professionals while ignoring other stakeholders, such as clients, suppliers, or regulators. Such exclusion may lead to a lack of complementary views that could have added value to understanding the pandemic’s impact on the sector. Potential biases about the origin and number of respondents should not be overlooked. Although the study’s sample of 15 participants is significant for an exploratory qualitative analysis like this one, it could be considered limited, reducing the breadth of perspectives and experiences captured. Nonetheless, the data obtained from the interviews should be seen as valuable information and experiences from experts that encourage reflection and guide future research. These findings provide an essential point of departure for further exploration of the construction industry’s dynamics in pandemic contexts.

Recommendations from this study to construction companies and engineers can be related to the fact that although the pandemic brought multiple challenges for the construction sector, it also brought some improvements and lessons learned regarding the skills required by construction professionals. Construction companies that account for changes in skills required by construction professionals may improve their hiring processes by seeking professionals who are more aware of workers’ health and safety, who know the importance of planning, and who can work well in teams and communicate properly while doing their job.

Recommendations for future research include researching the construction industry internationally to compare the skills professionals need in different regions to compare how skills requirements vary by region of the world. This would help identify both similarities and differences across the globe. Additionally, it is suggested that longitudinal studies be implemented to track changes and adaptations in these skills in response to market changes and technological advancements. To ensure more reliable and representative results, it is recommended that researchers expand the sample population and diversify data collection methods. This could include incorporating quantitative analysis through widely distributed surveys alongside qualitative research. A mixed-methods approach might provide a more comprehensive view of trends in the construction industry.

6. Conclusions

This study analyzed changes in skills required for construction professionals due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile. The study examined three stages: before, during, and after the pandemic, leveraging construction skills required by professionals from the literature to understand skills required before the pandemic. Then, the study qualitatively analyzed interviews to identify changes in skills required by construction professionals due to the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., during and after). This study analyzed the changes in 40 skills required for construction professionals and grouped them into four categories: interpersonal, leadership, technical and analytical, and individual skills.

Our study found that planning (S13), effective communication (S1), adaptability to change (S30), teamwork (S2), and stress management (S36) were more prominent skills due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The results revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly changed the required skills for construction professionals. The study highlights a shift towards skills like digital communication, adaptability, and stress management, which are necessary to maintain efficiency, collaboration, and resilience in a dynamic work environment like the one imposed by the pandemic. These findings offer valuable insights into evolving demands and how professional skills adapt to new challenges, like those presented by the pandemic. Such insights are helpful for construction managers, as they can use this information to foster human talent development in their construction teams and companies from now on. Additionally, industry professionals can leverage these findings to strengthen their capabilities and address complex industry challenges more effectively. Consequently, this study contributes to the existing literature by detailing how skills valued in the construction field changed during the COVID-19 pandemic and, as such, contributing to theorizing the consequences of the pandemic in the construction sector. Furthermore, our study contributes to practice by offering construction employers relevant information to improve recruitment and selection processes, adapting to the sector’s post-pandemic reality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A. and K.O.; Data curation, K.O.; Formal analysis, K.O., L.A.S., O.S. and B.N.; Funding acquisition, L.S.-V.; Investigation, O.S. and L.S.-V.; Methodology, F.A. and K.O.; Resources, L.S.-V.; Supervision, O.S.; Validation, F.A. and O.S.; Visualization, L.A.S. and B.N.; Writing—original draft, F.A.; Writing—review and editing, L.A.S., L.S.-V. and B.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the internal funding from Universidad Técnica Federico Santa Maria number PI LIR 23-17. Felipe Araya, Luis Salazar, and Katherine Olivari are greatly appreciated for the funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of La Frontera (Protocol 094/19 approved 9 October 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Interview Questions

- (1)

- Indicate your profession.

- (2)

- How many years have you been working in the construction industry?

- (3)

- Within the construction industry, what is your specialty?

- (4)

- During your professional career, what positions have you held?

- (5)

- Before the arrival of the pandemic, what would you consider to be the skills required for a professional to perform well in the construction industry? (Indicate at least ten skills).

- (6)

- Once the pandemic started, indicate which skills for the performance of a construction professional were enhanced.

- (7)

- How and why do you think this occurred among the skills that were enhanced?

- (8)

- In a post-pandemic context, what skills do you consider necessary for a construction professional’s good performance?

Appendix B. Skills Dictionary with Definitions and Examples

| Category | Id | Skills | Description | Example |

| Interpersonal Skills | S1 | Effective communication | Ability to express ideas clearly and understandably, convey messages effectively, and adapt the communication style according to the audience. | “We had to communicate better, both because of people’s emotional charge and the new forms of (virtual) communication.” |

| S2 | Teamwork | Ability to collaborate and work effectively in groups, taking advantage of individual strengths, and respecting the opinions and contributions of others. | “It’s a crucial skill for a professional, as you have to work with different teams and people, suppliers, customers, clients, principals, etc., and you have to make the project work.” | |

| S3 | Listening skills | Ability to pay active attention to others, understand and process information received, and respond appropriately. | “In the online format, it became more important to be able to listen to each other and wait your turn.” | |

| S4 | Writing skills | Ability to write and convey ideas coherently and persuasively in writing. | “During the pandemic, information in written format (e-mail, messaging applications) was more frequent, good writing was essential for good understanding.” | |

| S5 | Empathy | Ability to understand and share the feelings and perspectives of others, showing consideration and compassion. | “It’s always important to be empathetic with each other, especially your team; you never know when they’re having a hard time.” | |

| S6 | Oratory | Effective public speaking skills, with the ability to communicate in an impactful and persuasive manner with an audience. | “To motivate them and talk to them, I had to enhance my public speaking skills to make myself understood much better.” | |

| S7 | Speaking in public | Ability to communicate and present oneself to a group of people effectively, conveying the message clearly and confidently. | “It is important to know how to express instructions correctly, especially to the workers, and to do it so that they can listen to you and understand.” | |

| S8 | Negotiation | Ability to seek mutually beneficial agreements and constructively handle differences of opinion or interests. | “It became essential mainly to reach agreements with suppliers and customers.” | |

| S9 | Conflict management | Ability to manage differences and disputes effectively, promoting communication, negotiation, and peaceful problem-solving. | “You will have conflicts everywhere, but knowing how to deal with them is very important in this field.” | |

| S10 | Assertiveness | Ability to express opinions, desires, and needs clearly, respectfully, and assertively without being aggressive or passive. | “You had to be careful what you said; people were under more pressure than before.” | |

| Leadership Skills | S11 | Leadership | Ability to express opinions, desires, and needs clearly, respectfully, and assertively without being aggressive or passive. | “It was important to have the ability to lead well during this period; everyone had their internal struggle, but you had to finish the project.” |

| S12 | Delegation skills | Ability to effectively assign responsibilities and authority to team members, considering individual strengths and skills. | “Overwork is never good; learning to delegate and trust your team will improve things.” | |

| S13 | Planning | Ability to develop strategies, set goals, and create action plans to achieve desired objectives. | “Planning was crucial for both on-site planning and your planning.” | |

| S14 | Establishment of objectives | Ability to define clear and achievable goals, both individually and as a team, and communicate them effectively. | “The project’s success is closely linked to being clear about your objectives and how to reach them.” | |

| S15 | Change management | Ability to effectively lead and manage change in the organization or team. Addressing resistance, fostering adaptability, and managing emotions and concerns of team members during the process. | “A team, a company that does not change and does not adjust to the new reality, can be detrimental.” | |

| S16 | Motivation | Ability to inspire and stimulate team members to do their best. Includes recognition and positive reinforcement and the creation of a motivating and rewarding environment. | “Construction is a complicated industry, and with the pandemic, it was worse; keeping your team and workers motivated was very important.” | |

| S17 | Team management | Ability to organize and synchronize the activities and efforts of team members, ensuring effective collaboration and efficiency in achieving common objectives. | “During the pandemic, coordinating work, especially administrative work, was complex, as some were on-site, and others were teleworking.” | |

| S18 | Decision-making | Ability to analyze situations, evaluate options, and make informed and effective decisions, considering different perspectives, manage risks and consequences, and assume responsibility for decisions. | “The ability to make decisions in times of stress will always be welcomed in a professional; it is crucial to their development as a professional.” | |

| Technical and Analytical Skills | S19 | Computer skills | Ability to efficiently use computer tools and software for data management, reporting, information analysis, and other related tasks. | “Many of the processes went digital, and there were significant challenges at the beginning in knowing how to use the new platforms.” |

| S20 | Problem-solving | Ability to identify, analyze, and find effective solutions to challenges and obstacles in the work environment. | “Construction is always full of decisions and problems; knowing how to handle them and bring them to a successful conclusion is fundamental for a professional.” | |

| S21 | Critical thinking | It consists of objectively analyzing and evaluating information and arguments, identifying assumptions, detecting inconsistencies, and making informed decisions. | “The ability to think critically before problems or options is super important for a builder.” | |

| S22 | Creativity | Ability to generate novel ideas, find original solutions, and think outside the box. Proposes non-traditional approaches to address problems or challenges. | “In this complex time, we had to be creative for the problems we faced, and doing what you could with what you had was critical to getting by.” | |

| S23 | Organization | Ability to structure and efficiently manage information, resources, and tasks. It includes establishing priorities, planning, setting goals, and maintaining an orderly and systematic approach to work. | “It was essential for critical moments, mainly when there were quarantines or suspension of activity or delays.” | |

| S24 | Time management | Ability to plan and use time effectively, establish priorities, avoid procrastination, and optimize productivity in completing tasks and projects. | “Shortages of materials, poor productivity, and delays in general required an ability to manage your times and those of the site.” | |

| S25 | Cost management | Ability to control and optimize financial resources allocated to projects, tasks, or activities, ensuring efficient use of resources and minimizing un-necessary costs. | “Everything went up due to shortages, and labor became more expensive; no doubt projects had to take more notice.” | |

| S26 | Financial management | Ability to manage and make decisions related to the financial aspects of a project, department, or company. Includes financial concepts, budgeting, cash flow management, and analysis of economic indicators. | “The financial problems were more than known in construction; those who did not know how to manage it had complex problems.” | |

| S27 | Risk management | Ability to identify, assess, and manage potential risks associated with projects, concessions, or work situations. | “Construction is risky, but the appearance of the virus added a new variable to cover, and we had to deal with it.” | |

| S28 | Productivity management | Ability to optimize efficiency and performance in executing tasks and projects, using techniques and tools to improve processes and projects. | “Companies failed to realize the serious productivity problem that workers and their direct staff were having.” | |

| Individual Skills | S29 | Responsibility | Ability to assume the responsibilities of assigned tasks and meet commitments. Includes being reliable, meeting deadlines, and delivering quality results. | “It is a skill not only for the construction industry but for life in general, to be responsible for your actions and words; it speaks well as a person and professional.” |

| S30 | Adaptability to change | Ability to adjust and thrive in new or changing situations. Includes willingness to learn, flexibility, and openness to face and adapt to new challenges. | “The pandemic was full of changes and new challenges never seen before; whoever did not adapt was left behind.” | |

| S31 | Willingness to learn | The attitude of being open to continuous learning and personal development. Includes intellectual curiosity, active pursuit of knowledge, and willingness to acquire new skills and competencies. | “This capability should be important for those who are just starting as well as those who have been around for years.” | |

| S32 | Flexibility | Ability to adapt to different circumstances, perspectives, and requirements. Includes the ability to adjust plans and approaches, find creative solutions, and work effectively in changing environments. | “The new normal experienced in the pandemic required people who were flexible to this new scenario.” | |

| S33 | Patience | Ability to remain calm and composed in challenging or frustrating situations. Includes tolerance for delay and the ability to handle pressure. | “Construction is a stressful environment, and living with different people is difficult; you must learn to develop it as much as possible.” | |

| S34 | Reliability and honesty/ethical issues | It involves consistency and integrity in personal and professional conduct. It includes reliability in keeping promises, honesty in communication, and adherence to ethical and moral principles. | “Communicating problems or difficulties is important in a project; it speaks very well of you.” | |

| S35 | Determination | Ability to stay focused, persist, and overcome obstacles to achieve goals and objectives. It includes motivation, resilience, and the willingness to continue to strive. | “During the pandemic, determination in your actions and moving the company or the project forward was critical. | |

| S36 | Stress management | Ability to effectively manage emotional pressures and tensions. Includes stress management techniques, emotional self-control, and the ability to remain calm in stressful situations. | “Now you had to deal with more than your normal burden, the health checks, the contagions, and the financial burden.” | |

| S37 | Personal Productivity | Ability to manage time and resources efficiently to achieve optimal results. | “The way of producing change. Productivity in the office was tied to protocols, and telework productivity was tied to the home context.” |

Appendix C. Category Skills Dictionary

| Category | Description |

| Interpersonal Skills | These skills are related to the ability to interact with others effectively and empathetically, whether in individual or group situations. These skills are related to establishing positive connections, understanding others, and working productively in teams. |

| Leadership Skills | These skills are related to leading, influencing, and guiding others towards achieving goals and objectives. They include technical aspects and interpersonal and management skills, which allow a leader to motivate, inspire, and coordinate team members to maximize their performance and achieve successful results. |

| Technical and Analytical Skills | These skills are related to the abilities and competencies associated with the mastery of specific technical knowledge and the ability to analyze and solve problems. These skills are critical in professional environments that require an analytical, technical, and data-driven approach. |

| Individual Skills | This category refers to skills and attitudes related to personal development and management. These skills are essential for personal growth, adaptation to change, and efficiency in the workplace. |

References

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J. Risk identification and responses of tunnel construction management during the COVID-19 pan-demic. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6620539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, T.; Alisjahbana, A.S. The Initial Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Regional Economies in Indonesia: Structural Changes and Regional Income Inequality. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Rasoulinezhad, E.; Sarker, T.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Effects of COVID-19 on Global Financial Markets: Evidence from Qualitative Research for Developed and Developing Economies. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2023, 35, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayat, M.; Kang, C.W. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the construction sector: A systemized review, Engineering. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 734–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, F.; Poblete, P.; Salazar, L.A.; Sánchez, O.; Sierra-Varela, L.; Filun, Á. Exploring the Influence of Construction Companies Characteristics on Their Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Chilean Context. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, B.; Cabrera, T.; Duarte, J.; García, N.; Hernández, A.; Pérez, J.; Sasmay, A.; Signorini, V.; Talbot-Wright, H. COVID-19: Evolución, efectos y políticas adoptadas en Chile y el Mundo. Publ. Dir. Presup. Minist. Hacienda 2022, 28, 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de Chile. Paso a Paso-Gob.cl. 2020. Available online: https://www.gob.cl/pasoapaso/ (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Cámara Chilena de la Construcción. Protocolo Sanitario Para Obras de Construcción. 2020, pp. 1–5. Available online: https://issuu.com/camaraconstruccion/docs/protocolo-sanitario-obras-de-construccion (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Stride, M.; Renukappa, S.; Suresh, S.; Egbu, C. The effects of COVID-19 pandemic on the UK construction industry and the process of future-proofing business. Constr. Innov. 2023, 23, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, F. Modeling the influence of multiskilled construction workers in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic using an agent-based approach. Rev. Constr. 2022, 21, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Araya, F.; Ogalde, K.; Sierra, L. A Critical Review of Impacts from the COVID-19 Pandemic in Construction Projects: What Have We Learned? In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2024, Des Moines, IA, USA, 20–23 March 2024; pp. 621–631. [Google Scholar]

- Sutterby, P.; Wang, X.; Li, H.X.; Ji, Y. The impact of COVID-19 on construction supply chain management: An Australian case study. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 3098–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Xie, K.; Gui, P. Dynamic adjustment mechanism and differential game model construction of mask emergency supply chain cooperation based on covid-19 outbreak. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casady, C.B.; Baxter, D. Pandemics, public-private partnerships (PPPs), and force majeure| COVID-19 expectations and implications. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajmani, H.; Ahmed, S.; El-Sayegh, S.M. Factors causing delays in the UAE construction industry amid the Covid-19 pan-demic. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2023, 29, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.S.U.; Shafiq, M.T.; Afzal, M. Impact of COVID-19 on project performance in the UAE construction industry, Journal of Engineering. Des. Technol. 2022, 20, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, F.; Sierra, L. Influence between COVID-19 impacts and project stakeholders in Chilean construction projects. Sustainaility 2021, 13, 10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaad, R.; El-Adaway, I.H. Guidelines for Responding to COVID-19 Pandemic: Best Practices, Impacts, and Future Re-search Directions. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 06021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharef, A.; Banerjee, S.; Uddin, S.M.J.; Albert, A.; Jaselskis, E. Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the United States construction industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esa, M.B.; Ibrahim, F.S.B.; Kamal, E.B.M. Covid-19 pandemic lockdown: The consequences towards project success in ma-laysian construction industry. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. 2020, 5, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M.F.; Eid, A.F.; Khodeir, L.M. Challenges affecting efficient management of virtual teams in con-struction in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jin, Y.; Li, W.; Meng, Q.; Hu, X. Impacts of COVID-19 on construction project management: A life cycle perspective. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 3357–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, C.; Simpeh, F. Implementation challenges of COVID-19 safety measures at construction sites in South Africa. J. Facil. Manag. 2021, 19, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amien, D.H.; Elbeltagi, E.; Mashhour, I.M.; Ehab, A. Impact of COVID-19 on Construction Production Rate. Buildings 2023, 13, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohassen, A.S.; Alkhaldi, M.S.; Shaawat, M.E. The effects of COVID-19 on safety practices in construction projects. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, A.; Liang, Y.; Li, M.; Gonzalez, M.; Shahandashti, M.; Ashuri, B. Impact of COVID-19 on the Diversity of the Construc-tion Workforce. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2022, 23, 04022015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R. What’s it going to take? Lessons learned from COVID-19 and worker mental health in the Australian con-struction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2023, 41, 758–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onubi, H.O.; Hassan, A.S.; Yusof, N.; Bahdad, A.A.S. Moderating effect of project size on the relationship between COVID-19 safety protocols and economic performance of construction projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 2206–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, F.; Forcael, E.; Linfati, R. Workforce scheduling efficiency assessment in construction projects through a mul-ti-objective optimization model in the COVID-19 context. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, H. The impact of COVID-19 on construction labor productivity: The case of Turkey. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 3775–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, R.; Patil, K. UK Construction Industry Standing in the COVID-19 Era: Understanding the Impacts on Projects. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2023, 149, 04023014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Asis, C.A. The Lived Experiences of Construction Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: In Suburban Case. South Asian J. Soc. Stud. Econ. 2020, 8, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SKhaday; Li, K.W.; Dorloh, H. Factors Affecting Preventive Behaviors for Safety and Health at Work during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Thai Construction Workers. Healthcare 2023, 11, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S. Impact of Covid-19 on field and office workforce in construction industry. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2021, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, B.L.; Lim, B.T.H.; Kim, S. Working from Home during COVID-19 and Beyond: Exploring the Perceptions of Consultants in Construction. Buildings 2023, 13, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakeri, I.S.; Wahab, S.R.H.A.; Ani, A.I.C. The Technology Adaptation Measures to Reduce Impacts of Covid-19 Pandemic on the Construction Industry. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 31, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdulLateef, O.; Sanmargaraja, S.; Oni, O.; Anavhe, P.; Mewomo, C.M. An association rule mining model for the application of construction technologies during COVID-19. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 24, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.J.; Aziz, N.M. Embracing The Digital Twin for Construction Monitoring and Controlling to Mitigate the Impact of COVID-19. J. Des. Built Environ. 2022, 22, 40–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunnusi, M.; Hamma-adama, M.; Salman, H.; Kouider, T. COVID-19 pandemic: The effects and prospects in the construction industry. Int. J. Real Estate Stud. 2020, 14, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, F. COVID-19: Main challenges during construction stage. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 1817–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, F.; Sierra, L.; Basualto, D. Identifying the Impacts of COVID-19 on Chilean Construction Projects. Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. 2023, 251, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mhdawi, M.K.S.; Brito, M.P.; Nabi, M.A.; El-adaway, I.H.; Onggo, B.S. Capturing the Impact of COVID-19 on Con-struction Projects in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Iraq. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 05021015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avice, T. COVID-19: Lessons from a construction site, can we apply one industry safety protocol to another? J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 13, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Sueskun, I.; Díaz-González, J.A.; Acuña Juanbeltz, A.; Pérez-Murillo, A.; Garasa Jiménez, A.; García-Osés, V. Extramiana Cameno, E. Extramiana Cameno, Reincorporación al trabajo en el contexto de la pandemia de COVID-19 en sectores de industria y construcción en Navarra (España). Arch. Prev. Riesgos Laborales 2020, 23, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen, B.N.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Dinh, H.T.; Chu, A.T. The Impact of the COVID-19 on the Construction Industry in Vietnam. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2021, 8, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]