Abstract

As Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) gain traction in Chinese society, fostering sustainable entrepreneurship among university students has emerged as a key priority for universities and governments. Methods for increasing students’ sustainable entrepreneurship skills and knowledge for the creation of sustainable startups have attracted substantial attention. This study constructs a moderated mediation model based on entrepreneurial cognition theory to investigate the mediating roles of opportunity identification and attitude in the relationship between sustainable entrepreneurship education and sustainable entrepreneurial intention among university students, in addition to the moderating effect of empathy. The study surveyed 307 students from universities in the Yangtze River Delta region and employed hierarchical regression analysis to test the hypotheses. The results indicate that sustainable entrepreneurship education enhances students’ sustainable entrepreneurial intention by fostering their opportunity identification and attitude, and this enhancement effect is stronger when their level of empathy is higher. These findings enrich entrepreneurial cognition and empathy theories within the context of sustainable entrepreneurship and offer valuable insights for universities and policymakers in developing strategies to support sustainable entrepreneurship among university students.

1. Introduction

The global discourse on sustainable development goals increasingly stresses the need to align economic growth with environmental sustainability and societal well-being. Sustainable entrepreneurship, increasingly valued for addressing environmental and societal issues while achieving economic benefits [1,2], tackles climate change through renewable energy solutions, enhances community satisfaction with community-focused enterprises, and preserves biodiversity and ecosystems by promoting ecotourism and natural reserves [3]. Several research studies exploring the potential driving factors behind individuals’ willingness to establish or manage businesses oriented towards sustainable development—known as sustainable entrepreneurial intentions [4]—have consequently emerged. Notably, Millennials or Generation Y exhibit a heightened sense of environmental protection and social responsibility, coupled with a marked entrepreneurial inclination [5]. Thus, encouraging them to become next-generation sustainable entrepreneurs has become a new mission for governments and universities. Sustainable entrepreneurship education aims to equip aspiring entrepreneurs with the competencies and mindset to assess and seize business opportunities based on environmental conservation and social needs [6]. Sustainable entrepreneurship education integrates various traditional and experiential learning methods, such as classroom instruction, case discussions, and practical interactions, and it encompasses content related to sustainable development and entrepreneurship, such as sustainable business practices, energy and low-carbon economy, sustainability and the future, and sustainable marketing [7,8,9]. An increasing number of Chinese colleges and universities have initiated education programs in sustainable entrepreneurship to facilitate students’ engagement in sustainable startups [10]. Although fewer than 5% of young Chinese graduates opt to start businesses, it is encouraging that in recent years, there has been a significant increase in the number of sustainable development projects among university students’ entrepreneurship initiatives [11].

This trend has sparked significant scholarly interest in the effectiveness of sustainable entrepreneurship [12] and the associated intentions and behaviors [13,14]. Research has begun exploring how personality traits such as altruism, risk-taking, and values, in addition to external environmental factors, impact the intention to pursue sustainable entrepreneurship [15,16]. Recently, the focus has shifted from defining “who is an entrepreneur” to understanding “why individuals choose entrepreneurship” [17], emphasizing how entrepreneurial cognition influences opportunity identification and assessment [18,19]. However, the existing literature often lacks comprehensive models integrating internal cognitive processes and external environmental influences. Thus, investigating the cognitive processes behind the formation of sustainable entrepreneurial intention is critically important. Although entrepreneurship education is regarded as a significant factor influencing entrepreneurial intentions [20], previous studies have shown inconsistent results regarding its impact [21]. In particular, studies on sustainable entrepreneurial intentions are relatively limited, and some scholars have called for more focus on the boundary conditions of the effectiveness of sustainable education and its cognitive aspects [22]. Hence, this study aims to explore the cognitive process underlying the formation of sustainable entrepreneurial intentions, and it analyzes the internal mechanism and boundary conditions of how sustainable entrepreneurship education affects this process.

Entrepreneurial cognition theory posits that entrepreneurial decision-making is influenced by the entrepreneur’s cognitive factors, defined as the knowledge structures used to evaluate and judge opportunities [23,24]. This includes two pathways—opportunity information processing and evaluation, which are influenced by knowledge, experience, beliefs, and values [25,26,27], and which shape entrepreneurial intentions and actions [28]. We posit that opportunity identification serves as a pivotal juncture in the cognitive pathway of opportunity information processing [29,30], as evidenced by previous research that it involves individuals acquiring, processing, and interpreting the value of information [25,31] Sustainable entrepreneurship education, employing methods such as case analysis and practical training, serves as a significant source of personal knowledge and experience [32], thereby enhancing the ability to identify opportunities and influence entrepreneurial intentions. Simultaneously, attitude is considered pivotal in the information evaluation pathway, where an individual’s attitude is formed via the evaluation of behavioral beliefs and subjective value judgments [33]. Sustainable entrepreneurship education, as a catalyst for shaping individuals’ beliefs and values [34,35], can cultivate a positive mindset among entrepreneurs, thereby nurturing the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Consequently, this study aims to delineate how sustainable entrepreneurship education impacts the development of sustainable entrepreneurial intention via the cognitive routes of opportunity identification and attitude formation among university students. Furthermore, studies on entrepreneurial cognition highlight the significant influence of individual traits on entrepreneurial behavior, with particular attention being paid to empathy in recent years [36]. Empathy is defined as the understanding of other perspectives and exhibiting compassion and warmth towards them [37]. Although previous studies have consistently limited the role of empathy to the “social” dimension of social entrepreneurship [38], research calls for further investigation into the function of empathy in entrepreneurs’ exploration of opportunities [36]. We propose that individuals with high levels of empathy are better equipped to recognize valuable entrepreneurial opportunities and exhibit a greater willingness to address societal issues. Accordingly, this study examines how the influence of sustainable entrepreneurship education on opportunity identification and attitude is moderated by empathy.

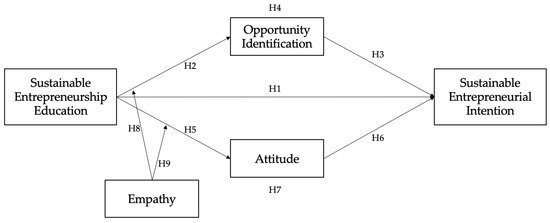

The primary purpose of this study is to develop a model for the formation of sustainable entrepreneurial intentions, thereby contributing to both theory and practice. This model addresses three key research questions: First, does sustainable entrepreneurship education promote the formation of sustainable entrepreneurial intentions? Second, through which mediating mechanisms does sustainable entrepreneurship education facilitate the formation of these intentions? Third, what are the boundary conditions for this facilitating mechanism? This study constructs and validates a model where sustainable entrepreneurship education enhances individuals’ opportunity identification capabilities and fosters positive attitudes towards sustainable entrepreneurship, thereby promoting the formation of intentions for sustainable entrepreneurship. This process is further moderated by empathy (as shown in Figure 1). The study offers three theoretical contributions. Firstly, it extends the focus beyond individual entrepreneurial traits by examining how sustainable entrepreneurship education, based on entrepreneurial cognition theory, influences sustainable entrepreneurial intentions. Secondly, using opportunity identification and attitude as dual mediators, this study explores the cognitive mechanisms of information processing and evaluation through which education impacts entrepreneurial intentions, highlighting the importance of opportunity identification. Thirdly, we introduce empathy as a moderating factor, clarifying how varying empathy levels affect opportunity identification and attitudes and addressing discrepancies in prior research. This research also holds practical significance, offering valuable insights and recommendations for policymakers and educators in universities with respect to enhancing education for sustainable development to elevate the success rates of university students in sustainable startups and provide greater contributions to solving societal and environmental problems.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

2. Literature and Hypotheses

2.1. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Education and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions

Sustainable entrepreneurship integrates economic, environmental, and social benefits, requiring entrepreneurs to utilize resources innovatively to tackle societal and environmental issues [39]. Globally, entrepreneurship education is increasingly recognized not only as a crucial component of high-quality education but also as a key driver for propelling nations and societies towards sustainable development goals [40]. Research has consistently linked entrepreneurship education with heightened entrepreneurial intentions [20,41], and recent studies have specifically explored its impact on sustainable entrepreneurial intentions [42,43,44]. A nascent body of research has also started to address the role of entrepreneurship education oriented towards sustainable development. Romero-Colmenares and Reyes-Rodríguez [35] have affirmed its positive influence on sustainable entrepreneurial intentions, while Agu et al. [8] did not find significant direct effects in their empirical study. The inconsistencies in these findings may stem from methodological limitations or cultural differences in educational practices across different regions. Consequently, the effectiveness and mechanisms of sustainable entrepreneurship education require further exploration and validation. Education is recognized as a vital tool; it equips individuals with the necessary knowledge, skills, and values to contribute to a sustainable future [45]. Currently, many colleges and universities, both domestically and internationally, have established sustainable entrepreneurship courses [6] aimed at undergraduates and postgraduates, including MBA and EMBA students.

We believe sustainable entrepreneurship education could foster university students’ intentions to engage in sustainable startups. Primarily, this educational focus is geared towards teaching students to efficiently utilize resources while pursuing economic growth, maintaining social equity, and exploring pathways to sustainable development that promote a harmonious coexistence among humanity, the environment, and society. Educational experiences can bolster the motivation to act, where experiences and knowledge pertaining to green education positively influence conference organizers’ willingness to host green events [46]. Moreover, individuals educated in sustainable entrepreneurship are more likely to focus on societal and environmental issues, adeptly identify market opportunities, and engage in sustainable development practices. Previous studies have shown that higher education equips students with specialized knowledge and business skills crucial for addressing sustainable development, thereby enhancing their capabilities and confidence to tackle global sustainability challenges [47]. Students who have undergone sustainable entrepreneurship education are poised to significantly contribute to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, such as constructing resource-efficient cities, promoting smart agriculture to facilitate forest restoration [48], advocating for sustainable consumption and production patterns, protecting biodiversity, and reducing the risk of natural disasters [49]. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1.

Sustainable entrepreneurship education is positively correlated with sustainable entrepreneurial intention.

2.2. The Dual Mediation Model of Sustainable Entrepreneurship Education and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention

Sustainable entrepreneurship requires the following: entrepreneurs who recognize the needs of society and the environment, seek opportunities to meet these needs, and build businesses around them. According to previous studies, the development of behavioral intentions is influenced by internal factors and external environmental factors [17]. External factors such as environmental conditions, education, and sociocultural elements indirectly affect an individual’s intentions and behaviors by influencing mediating variables, such as cognitive factors [50,51]. Entrepreneurship education is observed as a crucial means to alter individual cognition [32], potentially fostering the emergence of entrepreneurial intentions indirectly [52]. Entrepreneurial cognition theory posits that variations in decision-making among successful entrepreneurs are attributable to their enhanced ability to manage uncertainty and ambiguity through specific cognitive processes [23]. Entrepreneurs’ specific cognitive frameworks are their knowledge structures for processing, evaluating, and judging information [24]. These structures enable entrepreneurs to process environmental information and identify viable opportunities while evaluating this information to form attitudes. Thus, we introduce a dual mediation model where opportunity identification and attitude—as key cognitive variables—convey the impact of sustainable entrepreneurship education on the formation of sustainable entrepreneurial intentions.

Opportunity identification involves complex cognitive processes where individuals identify viable opportunities through information processing, which is particularly challenging for sustainable opportunities because of its complexity and rarity [18,53]. Sustainable entrepreneurship education enhances environmental scanning and information processing skills by providing knowledge and experience, helping individuals identify higher-quality opportunities [25,26]. Attitudes, formed through information evaluation [33], are crucial in shaping cognition [54]. This education fosters environmentally friendly and socially equitable beliefs, promoting a positive attitude towards sustainable entrepreneurship [13]. Overall, sustainable entrepreneurship education encourages individuals to process information and identify more business opportunities that can address significant societal and environmental issues, thereby increasing entrepreneurs’ feasibility cognition. When individuals believe that entrepreneurship can effectively solve those problems, their positive attitudes increase, bolstering their desirability cognition. Ultimately, both their feasibility and desirability cognition can promote the development of sustainable entrepreneurial intentions [55].

2.2.1. The Mediating Effect of Opportunity Identification

Sustainable entrepreneurship education can significantly enhance the identification of sustainable entrepreneurial opportunities. Sustainable entrepreneurs need to identify opportunities that yield multiple benefits to address market failures caused by social and environmental degradation [56]. This raises the bar for processing environmental information and identifying opportunities, making the perception of sustainable entrepreneurial opportunities potentially more challenging than that of traditional opportunities [53].

Firstly, individuals involved in sustainable entrepreneurship education possess business knowledge relevant to current environmental issues (such as water pollution, soil erosion, biodiversity degradation, etc.) and societal issues (such as poverty, exploitation, child welfare, etc.). McMullen and Shepherd [55] suggest that acquiring relevant knowledge reduces the uncertainty associated with third-person opportunities, increasing their transformation into first-person opportunities. Individuals with this education possess a deeper understanding of environmental and social values, which reduces their uncertainty, broadens their horizons, and enables them to capture new business opportunities from a more eco-friendly and socially responsible viewpoint. Secondly, sustainable entrepreneurship education, which includes case discussions and practical interactions, goes beyond traditional classroom instruction. It not only facilitates knowledge transfer but also significantly trains students’ cognition. For instance, cognitive training through the comparison of traditional and sustainable entrepreneurship cases assists students in building and strengthening cognitive models. These models enable them to better understand and process information related to entrepreneurship [57], thereby enhancing their ability to identify opportunities [58]. Third, sustainable entrepreneurship education emphasizes that students should explore and participate in practical sustainable projects. Practical experience, a significant influence on cognitive structures [26], equips individuals with a superior understanding of the market, technologies, and products. This experience enables them to use structural alignment processes to identify opportunities in unrelated markets [59]. Given the complexity of defining sustainable entrepreneurial opportunities, it is vital for individuals with specific cognitive styles to identify hidden opportunities through structural alignment. Consequently, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2.

Sustainable entrepreneurship education is positively correlated with opportunity identification.

We posit that the ability of entrepreneurs to identify opportunities can enhance university students’ sustainable entrepreneurial intentions. Firstly, extensive research has shown that opportunity identification is a key cognitive ability in entrepreneurial decision-making [60,61], with some scholars suggesting that the initiation of entrepreneurial activities is often triggered by opportunity identification [62,63]. Effective information processing enables individuals to spot potential business ventures. Those who perceive these opportunities as feasible and desirable are more likely to show a greater tendency towards risky entrepreneurship [64]. Furthermore, research by Bouarir et al. [65] corroborates that the recognition of business opportunities and entrepreneurship education has a positive and significant impact on entrepreneurial intentions. Secondly, the ability to anticipate market shifts, technological changes, or evolving consumer demands is a strong predictor of successful venture creation [66]. Only when individuals perceive opportunities that can protect ecosystems, counteract climate change, improve social equity, and help reduce poverty as profitable will they be able to implement these entrepreneurial ideas. Such implementation fosters the development of sustainable entrepreneurial intentions that encompass multiple benefits. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H3.

Opportunity identification is positively correlated with sustainable entrepreneurial intention.

Sustainable entrepreneurship education emphasizes principles and practices of sustainability, focusing on innovative methods for addressing societal issues and leveraging entrepreneurial activities for positive environmental impact. It encourages university students to adopt a systematic thinking approach [9], broadening the boundaries of their minds and enabling them to recognize new business opportunities from a more environmentally and socially friendly viewpoint. Additionally, such an education program improves university students’ abilities to identify sustainable business prospects by refining their cognitive frameworks. When these prospects are perceived as both desirable and feasible, students are more inclined to establish new startups [67], thereby demonstrating heightened entrepreneurial intentions. Therefore, we argue that sustainable entrepreneurship education equips students in identifying and connecting environmental and social information to business opportunities, thereby enhancing their ability to discern opportunities and promoting the development of sustainable entrepreneurial intentions. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4.

Opportunity identification mediates the relationship between sustainable entrepreneurship education and sustainable entrepreneurial intention.

2.2.2. The Mediating Effect of Attitude

We posit that sustainable entrepreneurship education significantly enhances university students’ positive attitudes towards sustainable entrepreneurial activities. Attitude is defined as an individual’s favorable or unfavorable evaluation of a behavior [68], reflecting their perception of the desirability of a certain behavior from a personal standpoint [69]. Compared to traditional entrepreneurship, assessing attitudes towards sustainable entrepreneurship requires examining not only financial outcomes but also the individual’s views and evaluations of an entrepreneurial model that contributes value to the community, society, and environment [70].

Initially, students who undergo education in sustainable entrepreneurship progressively develop positive perceptions towards such entrepreneurial endeavors by accumulating knowledge and skills related to the environment, ecology, entrepreneurship, and legislation [71]. Entrepreneurial decision-making is a cognitive processing activity [23], in which attitude, as a crucial component of individual cognition [54], evolves through the individual’s processing of knowledge, beliefs, and experiences [72]. Entrepreneurship education significantly influences students’ beliefs and knowledge, thereby serving as a pivotal tool in cultivating the entrepreneurial attitudes of prospective entrepreneurs [73]. Secondly, educational programs focused on sustainable development help students become aware of the global challenges faced by natural ecosystems and the public environment, such as soil degradation and resource scarcity caused by industrialization [74], and the disappearance of cultural customs and traditional knowledge resulting from a decline in minority groups [75]. Upon recognizing the aspects that require sustainable development, they are likely to cultivate values of equity, inclusion, and respect for nature [76]. Such awareness also fosters interest and motivation to address these challenges, enhancing a positive attitude toward the role of sustainable entrepreneurs. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H5.

Sustainable entrepreneurship education is positively correlated with attitudes.

We posit that individuals with a positive attitude towards sustainable entrepreneurship are more likely to engage in such startups. Firstly, an individual’s attitude reflects their preference for a particular behavior, which in turn influences their subsequent intention to act. Ajzen [33] underscores that attitude is a critical determinant of intention, corroborated by studies demonstrating its positive impact on entrepreneurial intentions [15,77]. Therefore, those with a positive disposition towards sustainable entrepreneurship are more likely to pursue such startups. Secondly, the benefits of sustainable entrepreneurs encompass personal benefits (economic interests) and benefits to others (environmental and social interests) [4]. The varied value individuals place on these benefits can lead to varying levels of desire, ultimately influencing their intention to pursue sustainable entrepreneurship. For example, the need to balance economic with non-economic benefits presents complex trade-offs that may deter individuals from pursuing sustainable entrepreneurial initiatives [70]. Thirdly, sustainable entrepreneurship requires integrating multiple values [3]. Therefore, evaluating the intent to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship must include not only traditional entrepreneurial considerations but also the challenges and preferences related to creating social and environmental value. Only individuals who prioritize these social and environmental outcomes are likely to develop a strong intention towards sustainable entrepreneurship. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H6.

Attitude is positively correlated with sustainable entrepreneurial intention.

Sustainable entrepreneurship education is designed to enhance students’ awareness of sustainability issues through experiential learning, resulting in the cultivation of values centered around sustainable development. This educational approach deepens students’ understanding of sustainable development knowledge and establishes corresponding beliefs and values [34], thereby fostering their enthusiasm and proactive attitudes towards exploring environmentally friendly solutions. Simultaneously, immersive educational activities such as community volunteer work and seaside water management efforts can prompt students to reflect on their values and moral beliefs [78]. Such experiences encourage them to reassess what is important and valuable to themselves, society, and the environment, resulting in the re-evaluation of the relationship between the natural environment, ecological communities, and commercial values. These positive attitudes can lead them to believe that entrepreneurship can effectively address these issues, thereby sparking feasibility cognition and fostering the desire to engage in sustainable startups. Consequently, we posit that sustainable entrepreneurship education equips students with pertinent knowledge and critical thinking skills. Through cognitive processes, it fosters positive attitudes toward sustainable entrepreneurship, ultimately enhancing their intentions to pursue such startups. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7.

Attitude mediates the relationship between sustainable entrepreneurship education and sustainable entrepreneurial intention.

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Empathy

In recent academic discourse, empathy has garnered significant attention in the realm of entrepreneurship [36], transcending mere psychological constructs. Empathy, in its essence, represents an innate capacity to comprehend and resonate with the sentiments of others [38,79]. Individuals with varying levels of empathy exhibit distinct reactions and perspectives towards interpersonal interactions and events. High-empathy individuals are adept at adopting diverse viewpoints, engaging in profound emotional resonance with others’ experiences, and crafting effectual solutions. These qualities are invaluable in the entrepreneurial landscape, where the ability to empathize fosters a deeper understanding of market dynamics, consumer preferences, and societal needs [80].

Empathy equips entrepreneurs with a powerful tool to discern market and technological gaps by adopting a customer-centric mindset. This approach not only aids in pinpointing lucrative business prospects but also aligns entrepreneurial endeavors with sustainable development goals. Individuals with high empathy can leverage phenomenal and factual knowledge to construct empathic models and envision unmet consumer needs [36], thereby facilitating the identification of satisfying opportunities that prioritize environmental protection and promote social equity. Conversely, individuals with lower levels of empathy lack sufficient vicarious imagination, making it challenging to leverage this knowledge to explore further innovative opportunities [36,80].

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H8.

Empathy moderates the relationship between sustainable entrepreneurship education and opportunity identification, and the positive relationship is stronger when the level of empathy is higher.

Moreover, empathy assists entrepreneurs by enabling them to resonate with others, thereby fostering a proactive attitude towards utilizing entrepreneurship to address societal and environmental issues. According to Mair and Noboa [81], individuals with high levels of empathy tend to carry out actions that benefit others. Sustainable development emphasizes coexistence among humans, society, and the environment, adhering to principles of ecological balance, social equity, and economic growth. Educated students are more attuned to the urgency of environmental hazards and human rights issues arising from social injustice. Highly empathic individuals are more likely to feel warmth, sympathy, and concern for those experiencing these issues [82], enhancing their propensity to positively engage in developing and implementing business strategies that benefit both society and the environment. In contrast, those with lower levels of empathy, despite having received education in sustainable entrepreneurship, may not develop a deep emotional connection with disadvantaged social groups. Consequently, they may lack a strong sense of responsibility with respect to addressing these challenges, resulting in a passive attitude towards solving these problems [83].

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H9.

Empathy moderates the relationship between sustainable entrepreneurship education and attitude, and the positive relationship is stronger when the level of empathy is higher.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

This study utilized a survey method to gather data from students across various disciplines and academic levels in universities within the Yangtze River Delta region of mainland China, including Zhejiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Anhui. The Yangtze River Delta region is a crucial area in China in leading sustainable development and achieving dual carbon goals, with its carbon emissions accounting for approximately one-fifth of the national total. Renowned as a hub for innovation and entrepreneurship, this region features leading entrepreneurial education programs and robust collaborations among industry, academia, and research. Additionally, the university student entrepreneurship ranking within this area is at the forefront nationally. Numerous universities have incrementally introduced sustainable entrepreneurship education tailored for undergraduate, master’s (including MBA), and doctoral students. As a result, university students are afforded extensive opportunities to participate in a range of educational programs and practical projects related to sustainable entrepreneurship, such as lectures, industry seminars, and competitions centered on sustainability themes.

Following the end of the spring/summer semester, we distributed survey links via online platforms (e.g., Questionnaire Star and Credamo) to students recruited through university forums from June to July 2023. A small portion of the survey data was also obtained by researchers who entered classrooms to conduct random interviews in person. All survey participants had a prior engagement in sustainable entrepreneurship courses and projects or participation in certain lectures. They had a basic understanding of the subject, and they were able to correctly comprehend the survey items and complete the questionnaire. They were informed that the survey was anonymous and voluntary and that the results would be confidential and used solely for academic research.

In this study, we distributed 380 questionnaires and received 329 responses. After excluding samples with missing items and failed attention tests, 307 valid responses remained, yielding an effective response rate of 80.8%. The final sample comprised 149 males (48.5%) and 158 females (51.5%). Most respondents (78.8%) were aged 18 to 25 years. By education level, undergraduates comprised 32.6%, master’s students comprised 39.4%, and doctoral students comprised 27.4%. Regarding fields of study, humanities and business represented 24.8%, science and engineering represented 50.8%, and life sciences and medicine represented 22.5%. Among the participants, 23.5% had entrepreneurial experience, while 76.5% did not.

3.2. Measures

The scales employed in this research were adapted from well-established English scales used in previous academic studies. Following the “translation and back-translation” method [84], the translation process was carried out collaboratively by PhD students who are fluent in English and the authors of this study; the consistency of the items in the scale and the content of the original scale were ensured. Insights from interviews with three students engaged in sustainable entrepreneurship education led to revisions in the survey questions. These were further refined through discussions with three professors in the related field. Before conducting the official survey, ten students from various majors were recruited to pre-fill the questionnaire, and the wording of the question items was improved to better suit university students. The questionnaire (see Table A1) utilized a 7-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Sustainable Entrepreneurship Education

We adapted the six-item scale developed by Truong et al. [14] to measure sustainable entrepreneurship education. A sample item is “The courses I took developed the skills I need to become a sustainable entrepreneur” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.855).

Opportunity Identification

We adapted the four-item scale developed by Chandler and Hanks [85] to evaluate the ability to identify opportunities. A sample item is “I can identify potential consumer or customer needs” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.830).

Attitude

We adapted the four-item scale developed by Thelken and de Jong [86] to evaluate the attitude toward sustainable entrepreneurship. A sample item is “The idea of creating a company with a focus on sustainable development is very appealing to me” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.827).

Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention

We adapted the four-item scale developed by Truong et al. [14] to evaluate the sustainable entrepreneurial intention. A sample item is “My entrepreneurship will prioritize social impact (e.g., creating jobs, reducing poverty, and improving quality of life)” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.841).

Empathy

We adapted the four-item scale developed by Davis [82] and Hockerts [38] to measure the level of empathy. A sample item is “When considering socially disadvantaged groups, I try to put myself in their shoes” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.785).

Control variables

Drawing on research regarding the relationship between educational level and previous entrepreneurial/work experience with entrepreneurship [87,88], we introduced the respondents’ educational level, major, and entrepreneurial experience as control variables in the study. Additionally, demographic variables such as gender and age were also included as control variables.

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability

This study utilized SPSS 26 and Mplus 8 to conduct reliability and validity tests. As shown in Table 1, the Cronbach’s α values for the variables all exceeded 0.75, indicating that all scales demonstrated good reliability. The composite reliability (CR) values were all above 0.7, suggesting that the scales have satisfactory convergent validity. The square root values of the average variance extracted (AVE) for the variables all exceeded the Pearson correlation coefficients, demonstrating strong discriminant validity.

Table 1.

Convergent validity and reliability.

The results of confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the five-factor model (χ2/df = 2.369; CFI = 0.908; SRMR = 0.054; RMSEA = 0.067) was significantly better than other models with fewer factors (as shown in Table 2), suggesting a good fit between the data and the model and good discriminant validity among constructs.

Table 2.

Results for confirmatory factor analyses.

4.2. Common Method Bias Tests

To mitigate the potential effects of common method bias resulting from data homogeneity, this study employed SPSS 26 to conduct Harman’s single-factor test across all indicators. The results extracted five factors, where the first factor explained 32.75% of the total variance, which is below the critical threshold of 40% proposed by Podsakoff et al. [89].This indicates that the negative impact of common method bias is not a concern in this research.

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

The study verified the means, standard deviations, and correlations among the variables, as shown in Table 3. Sustainable entrepreneurship education was significantly positively correlated with attitude (r = 0.48, p < 0.01), opportunity identification (r = 0.59, p < 0.01), and sustainable entrepreneurial intention (r = 0.36, p < 0.01). Furthermore, attitude (r = 0.38, p < 0.01) and opportunity identification (r = 0.38, p < 0.01) were both significantly positively correlated with sustainable entrepreneurial intention. Thus, the research hypotheses were preliminarily tested. In addition, the assumptions required for the validity of the hierarchical regression model were satisfied in our study. The correlation coefficients among the independent variables were all lower than 0.60, and the variance inflation factor (VIF) values of all independent variables were less than 10, indicating that there was no obvious multicollinearity problem.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

4.4. Hypothesis Tests

This study used hierarchical regression to test for mediating effects (as shown in Table 4), controlling for gender, age, education level, major, and entrepreneurial experience.

Table 4.

Results for the hierarchical regression analysis.

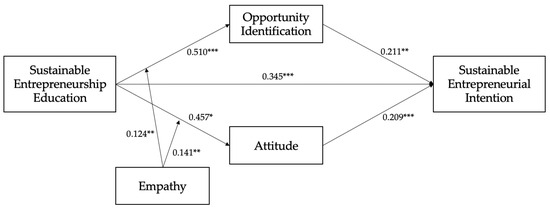

Sustainable entrepreneurship education exerted a significant positive impact on sustainable entrepreneurial intention (Model 1: β = 0.345, p < 0.001), opportunity identification (Model 3: β = 0.51, p < 0.001), and attitudes towards sustainable entrepreneurship (Model 5: β = 0.457, p < 0.05), thus supporting Hypotheses 1, 2, and 5. Furthermore, opportunity identification significantly positively influenced sustainable entrepreneurial intention (Model 2: β = 0.211, p < 0.01), as did attitude (Model 2: β = 0.209, p < 0.001), confirming Hypotheses 3 and 6. When sustainable entrepreneurship education, opportunity identification, and attitude were included simultaneously in the model for sustainable entrepreneurial intention, the direct effect of education on intention decreased but remained significant (Model 2: β = 0.142, p < 0.05), indicating partial mediation via opportunity identification and attitude.

To ensure consistency and stability in the analysis results, this study employed the bias-corrected bootstrap method using the PROCESS plugin in SPSS 26. We extracted 5000 bootstrap samples to evaluate the dual mediation roles of opportunity identification and attitude between sustainable entrepreneurship education and sustainable entrepreneurial intention. As detailed in Table 5, the total and direct effects were 0.342 (p < 0.001) and 0.141 (p < 0.05), respectively, both with 95% confidence intervals that exclude zero, affirming the significance of both the total and direct effects. The mediation effects were 0.107 for opportunity identification and 0.095 for attitude, with both effects within the 95% confidence intervals excluding zero. These findings validate the partial mediation roles of opportunity identification and attitude, confirming Hypotheses 4 and 7.

Table 5.

Results of parallel mediation model for the bootstrap analysis.

To examine moderating effects, hierarchical regression analyses were performed initially. In an effort to reduce multicollinearity, we centralized both the sustainable entrepreneurship education and empathy variables prior to generating their interaction term. Model 4 in Table 4 shows that the interaction between sustainable entrepreneurship education and empathy has a significant positive impact on opportunity identification (β = 0.124, p < 0.01); Model 6 in Table 4 demonstrates that this interaction also significantly positively affects attitude (β = 0.141, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypotheses 8 and 9 receive preliminary support (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of study results. Note(s): * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

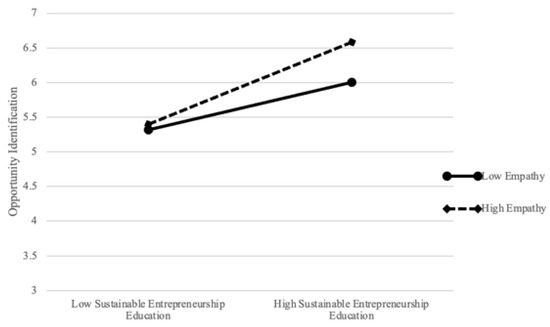

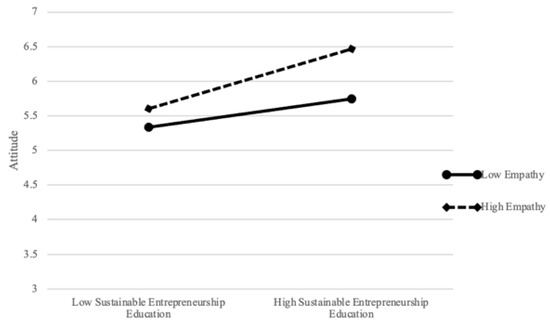

To further validate the moderating effect, we utilized the simple slope method as recommended by Aiken et al. [90] to plot the impacts of sustainable entrepreneurship education on opportunity identification and attitude at different empathy levels (mean ± 1SD). Compared to students with low empathy levels (β = 0.364, boot SE = 0.058, 95% CI = [0.249, 0.479]), those with high empathy levels demonstrate a stronger positive effect of sustainable entrepreneurship education on opportunity identification (β = 0.569, boot SE = 0.059, 95% CI = [0.453, 0.685]), indicating a steeper slope (as depicted in Figure 3). Similarly, Figure 4 shows that, compared to students with low empathy (β = 0.224, boot SE = 0.052, 95% CI = [0.121, 0.326]), those with high empathy levels experience a more significant positive effect of sustainable entrepreneurship education on their attitudes (β = 0.411, boot SE = 0.053, 95% CI = [0.307, 0.515]). Therefore, Hypotheses 8 and 9 are further supported.

Figure 3.

Moderating effect of sustainable entrepreneurship education on opportunity identification with respect to empathy.

Figure 4.

Moderating effect of sustainable entrepreneurship education on attitude with respect to empathy.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Our study provides significant contributions in three areas. First, responding to recent calls for research on sustainable entrepreneurship, we explored the possibility that sustainable entrepreneurship education influences sustainable entrepreneurial intentions. Extensive studies have explored the drivers of sustainable entrepreneurial intentions, including altruism, risk-taking, and personal values [16]. However, research that specifically examines the effectiveness of sustainable entrepreneurship education is limited and has produced inconsistent empirical findings [8,35]. The facilitative role and mechanisms of sustainable entrepreneurship education remain unclear. Our study demonstrates that exposure to sustainable entrepreneurship education can foster individuals’ motivation to establish sustainable businesses, thereby enriching the understanding of the relationship between sustainable entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial behavior.

Second, we examine sustainable entrepreneurship education from the perspective of entrepreneurial cognition, emphasizing cognitive training to help individuals identify business solutions for environmental and societal issues, fostering a positive attitude towards sustainable development, and thereby nurturing sustainable entrepreneurship intentions. Previous research predominantly applied the theory of planned behavior and entrepreneurial event theory to analyze drivers of such intentions [33,67]. However, empirical evidence often contradicted the expected mediating roles of subjective norms and perceived behavioral control [14,91], and it neglected the critical role of opportunity identification [92]. Therefore, existing intention models appear to be inadequate for responding to calls for research on specific types of entrepreneurship. Our study emphasizes the importance of opportunity identification in sustainable entrepreneurship, a complex domain involving multiple stakeholders such as governments, consumers, suppliers, and communities. Entrepreneurs must balance these stakeholders’ needs and expectations to uncover opportunities that provide environmental and social value, which are often overlooked by others. By incorporating attitudes and opportunity identification as mediating variables, our study enriches the discussion of theories of sustainable entrepreneurial intention and extends the application of entrepreneurial cognition theory in the field of sustainable entrepreneurship education.

Third, our research integrates empathy into the theoretical framework of sustainable entrepreneurship, examining how different levels of empathy moderate the impact of sustainable entrepreneurship education. Prior studies have reported inconsistent results on whether education bolsters individual entrepreneurial intentions [21,93]. These inconsistencies may arise because the skills and knowledge from entrepreneurship courses do not automatically result in positive evaluations of sustainable entrepreneurship, and opportunity identification is also influenced by personal traits [94]. In response, this study identifies empathy as a critical boundary condition. Our findings demonstrate that individual empathy levels significantly moderate the effects of sustainable entrepreneurship education on opportunity identification and attitudes, clarifying previous disparities. Highly empathetic individuals, educated in sustainable entrepreneurship, are more adept at identifying sustainable opportunities from a consumer’s perspective. Their enhanced concern for environmental and societal issues potentially increases their likelihood of initiating sustainable business projects. This research study moves beyond traditional views in entrepreneurship studies that consider empathy solely within the dimension of social entrepreneurship [38]. Instead, it highlights empathy’s broader importance in sustainable entrepreneurship—a field requiring a synthesis of social, environmental, and economic factors—and contributes to refining the theory of entrepreneurship education.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our research offers valuable practical insights for universities and policymakers. In alignment with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals initiative, the global focus on sustainable development and entrepreneurship has annually increased. Consequently, universities and policymakers must recognize the pivotal role of the younger generation in driving social development and entrepreneurship and foster a thriving and sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Firstly, universities should vigorously promote entrepreneurship education focused on sustainable development and embed sustainable development principles and practices into their entrepreneurship curricula, making them an integral part of students’ learning experiences and thereby enhancing students’ awareness and sense of responsibility towards societal and environmental challenges. This includes incorporating modules on environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and economic viability, in addition to alongside traditional entrepreneurship topics such as business planning, marketing, and finance.

Secondly, in order to ensure the quality and consistency of education and training, universities and policymakers should set standards for sustainable entrepreneurship education. They should provide ongoing training and support to educators to help them stay abreast of the latest research, pedagogical techniques, and best practices in delivering sustainable development content. Our research proposes a robust cognitive training framework for teachers guiding students in grasping cutting-edge knowledge and emerging technologies in sustainability through green case studies, designing sustainable business models, engaging in entrepreneurship project practice, and participating in internships at sustainable enterprises. Additionally, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration through initiatives such as brainstorming sessions and team discussions can stimulate innovative cross-industry sustainable entrepreneurship opportunities, encouraging students to conceive and execute projects that contribute meaningfully to societal well-being.

Lastly, recognizing the significance of emotional intelligence and empathy in shaping students’ engagement and success, we stress the need for a tailored approach to education. For students with heightened empathy, educational strategies that emphasize emotional engagement, including immersive case studies and field research, should be prioritized. This personalized approach not only nurtures their interest but also fosters active participation and leadership in sustainable initiatives, ultimately enhancing the overall effectiveness of sustainable entrepreneurship education.

By integrating these strategies—integrating sustainability into entrepreneurship curricula, training educators, and setting standards and adopting a robust cognitive training framework and a tailored educational approach—universities, policymakers, and educators can collaboratively create a robust and impactful sustainable entrepreneurship education ecosystem. This ecosystem will prepare students for the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, cultivating a new generation of socially responsible and environmentally conscious entrepreneurs.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. Firstly, our model did not explore actual sustainable entrepreneurship behavior due to the delayed impact of entrepreneurship education, which is estimated to involve a ten-year lag from education to business initiation [95]. Therefore, sustainable entrepreneurial intention was used as the outcome variable in this study. Future research could benefit from longitudinal studies, such as maintaining contact with students who have participated in sustainable entrepreneurship education and conducting follow-up surveys three, six, and nine years after graduation. These surveys would aim to explore the role of sustainable entrepreneurship education in transforming entrepreneurial intentions into actual entrepreneurial activities. Secondly, this study solely employed a questionnaire survey as the research method, with variable data subjectively provided by the students. This approach may introduce common method bias and self-report bias. Considering the scientific principles of the research method, future research can adopt a combination of multiple research methods, such as integrating case studies with longitudinal surveys, to enhance the reliability of the findings. Thirdly, the survey data used in this study were primarily collected from universities in the Yangtze River Delta region. Although this sampling method controls for background variables such as regional policies and cultural environments, it may limit the external validity of the research findings. Future studies should expand the geographic scope of the sample to increase the breadth, randomness, and scientific consideration of sample selection, enhancing the generalizability of the theoretical model. Research also highlights the impact of cultural background, major, educational level, and prior experiences on entrepreneurial intentions [21,77]. For instance, prior business experience may reduce willingness towards sustainable entrepreneurship [53]. Consequently, future studies could explore the varying effects of sustainable entrepreneurship education on students from diverse cultural backgrounds and those with different majors and educational levels.

5.4. Conclusions

In recent years, scholars have started to focus on the antecedents of sustainable entrepreneurial intention to explore methods for enhancing and promoting sustainable development. Moving beyond earlier studies that primarily examined the influence of personal traits, this study centers on how sustainable entrepreneurship education influences individual intentions through cognitive processes based on the entrepreneurial cognition perspective. Drawing on a survey of 307 students from universities in the Yangtze River Delta area, our findings reveal that sustainable entrepreneurship education significantly boosts sustainable entrepreneurial intentions by enhancing students’ attitudes and improving opportunity identification, with these effects further amplified in individuals with higher empathy. This study not only supplements prior theoretical research on the antecedents of sustainable entrepreneurial intention but also enriches the application of entrepreneurial cognition theory and empathy theory in the field of sustainable entrepreneurship education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and H.H.; Methodology, J.H. and Z.F.; Software, J.H.; Validation, J.H. and H.H.; Formal analysis, J.H. and H.H.; Investigation, J.H. and Z.F.; Resources, J.H. and Z.W.; Data curation, J.H.; Writing—original draft, J.H.; Writing—review & editing, J.H. and H.H.; Visualization, J.H.; Supervision, Z.W. and H.H.; Project administration, J.H. and Z.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire Item.

Table A1.

Questionnaire Item.

| Sustainable Entrepreneurship Education (Truong et al., 2022) [14] |

| 1. My university is the ideal place for me to learn about sustainable entrepreneurship |

| 2. My university encourages students to create sustainable businesses |

| 3. My university has an innovative atmosphere, which has inspired my interest in sustainable entrepreneurship |

| 4. The courses I took increased my knowledge of sustainable entrepreneurship |

| 5. The courses I took developed the skills I need to become a sustainable entrepreneur |

| 6. The courses I took were helpful in discovering potential opportunities for sustainable entrepreneurship |

| Opportunity Identification (Chandler and Hanks, 1994) [85] |

| 1. I can identify potential customer needs |

| 2. I always actively look for products or services that can bring real benefits to customers |

| 3. I can develop new products that people want or find ways to improve existing products |

| 4. I can discover and seize high-quality business opportunities |

| Attitude (Thelken and de Jong, 2020) [86] |

| 1. I believe that being a sustainable entrepreneur implies more advantages than disadvantages |

| 2. The idea of creating a company with a focus on sustainable development is very appealing to me |

| 3. If I have the opportunity and resources, I would definitely prefer to start a sustainable business |

| 4. Being a sustainable entrepreneur would make me feel very proud |

| Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention (Truong et al., 2022) [14] |

| 1. My entrepreneurship will prioritize social impact (e.g., creating jobs, reducing poverty, and improving quality of life) |

| 2. My entrepreneurship will prioritize environmental impacts (e.g., waste treatment, giving priority to the use of renewable energy) |

| 3. My entrepreneurship will contribute to sustainable development |

| 4. If I set up my own business, I would prefer societal goods rather than economic gains |

| Empathy (Davis, 1980; Hockerts, 2017) [38,82] |

| 1. When considering socially disadvantaged groups, I try to put myself in their shoes |

| 2. Seeing socially disadvantaged groups triggers an emotional response in me |

| 3. Sometimes, I try to better understand them by imagining how things look from someone else’s perspective |

| 4. I feel sympathy for socially marginalized people and wish to protect them |

References

- Youssef, A.B.; Boubaker, S.; Omri, A. Entrepreneurship and sustainability: The need for innovative and institutional solutions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 129, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Argade, P.; Barkemeyer, R.; Salignac, F. Trends and patterns in sustainable entrepreneurship research: A bibliometric review and research agenda. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 106092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; McMullen, J.S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, A.M.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, S.A.; Sherbin, L.; Sumberg, K. How Gen Y and Boomers will reshape your agenda. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Diepolder, C.S.; Weitzel, H.; Huwer, J. Competence frameworks of sustainable entrepreneurship: A systematic review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Goyal, D.P.; Singh, A. Systematic review on sustainable entrepreneurship education (SEE): A framework and analysis. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 17, 372–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, A.G.; Kalu, O.O.; Esi-Ubani, C.O.; Agu, P.C. Drivers of sustainable entrepreneurial intentions among university students: An integrated model from a developing world context. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 659–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Raimundo, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic Bibliometric Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; An, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, P. The role of entrepreneurship policy in college students’ entrepreneurial intention: The intermediary role of entrepreneurial practice and entrepreneurial spirit. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 585698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2023/2024 Global Report: 25 Years and Growing; GEM: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, P.; Cohen, B. Sustainable entrepreneurship research: Taking stock and looking ahead. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 300–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middermann, L.H.; Kratzer, J.; Perner, S. The impact of environmental risk exposure on the determinants of sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, H.T.; Le, T.P.; Pham, H.T.T.; Do, D.A.; Pham, T.T. A mixed approach to understanding sustainable entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargani, G.R.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Chandio, A.A.; Hussain, M.; Khan, N. Endorsing sustainable enterprises among promising entrepreneurs: A comparative study of factor-driven economy and efficiency-driven economy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 735127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.M.; Suchek, N.; Gomes, S. The antecedents of sustainability-oriented entrepreneurial intentions: An exploratory study of Angolan higher education students. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 391, 136236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, K.G.; Scott, L.R. Person, process, choice: The psychology of new venture creation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1992, 16, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; McMullen, J.S.; Jennings, P.D. The formation of opportunity beliefs: Overcoming ignorance and reducing doubt. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2007, 1, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghely, I.P.; Julien, P.A. Are opportunities recognized or constructed?: An information perspective on entrepreneurial opportunity identification. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F. Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2008, 4, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T.J.; Qian, S.; Miao, C.; Fiet, J.O. The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta–analytic review. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.S.; González-Gómez, D. Cognitive, Affective, Behavioral, and Multidimensional Domain Research in STEM Education: Active Approaches and Methods Towards Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 881153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarasvathy, S.D. Making it happen: Beyond theories of the firm to theories of firm design. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2004, 28, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Busenitz, L.; Lant, T.; McDougall, P.P.; Morse, E.A.; Smith, J.B. Toward a theory of entrepreneurial cognition: Rethinking the people side of entrepreneurship research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 27, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, D.A.; Shepherd, D.A. Technology-market combinations and the identification of entrepreneurial opportunities: An investigation of the opportunity-individual nexus. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 753–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, B.A.; Shepherd, D.A. Making the most of failure experiences: Exploring the relationship between business failure and the identification of business opportunities. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2016, 40, 457–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukkanen, M. What lies behind entrepreneurial intentions? Exploring nascent entrepreneurs’ early belief systems. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2022, 28, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Houghton, S.M.; Aquino, K. Cognitive biases, risk perception, and venture formation: How individuals decide to start companies. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Korri, J.S.; Yu, J. Cognition and international entrepreneurship: Implications for research on international opportunity recognition and exploitation. Int. Bus. Rev. 2005, 14, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleptsov, A.; Anand, J. Exercising entrepreneurial opportunities: The role of information-gathering and information-processing capabilities of the firm. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2008, 2, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S. Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.F.; Santos, S.C.; Wach, D.; Caetano, A. Recognizing opportunities across campus: The effects of cognitive training and entrepreneurial passion on the business opportunity prototype. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2018, 56, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P.; Secundo, G.; Mele, G.; Passiante, G. Sustainable entrepreneurship education for circular economy: Emerging perspectives in Europe. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 2096–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Colmenares, L.M.; Reyes-Rodríguez, J.F. Sustainable entrepreneurial intentions: Exploration of a model based on the theory of planned behaviour among university students in north-east Colombia. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packard, M.D.; Burnham, T.A. Do we understand each other? Toward a simulated empathy theory for entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 106076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H. Empathy and prosocial behavior. In The Oxford Handbook of Prosocial Behavior; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 282–306. [Google Scholar]

- Hockerts, K. Determinants of social entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: Studying entrepreneurial action linking “what is to be sustained” with “what is to be developed”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, F.; Jones, O.; Jayawarna, D. Promoting sustainable development: The role of entrepreneurship education. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 31, 841–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippa, P.; Ferruzzi, G.; Holienka, M.; Capaldo, G.; Coduras, A. What drives university engineering students to become entrepreneurs? Finding different recipes using a configuration approach. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 353–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, P.; Fischer, D.; Wamsler, C. Mindfulness, education, and the sustainable development goals. In Quality Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera-Sánchez, J.J.; Pérez-Pérez, C.; González-Torres, T. Exploring the knowledge structure of entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 19, 563–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahrani, A.A. Promoting sustainable entrepreneurship in training and education: The role of entrepreneurial culture. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 963549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Why Education is the Key to Sustainable Development. 2020. Available online: www.weforum.org (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Boo, S.; Park, E. An examination of green intention: The effect of environmental knowledge and educational experiences on meeting planners’ implementation of green meeting practices. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1129–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Rudhumbu, N.; Shumba, J.; Olumide, A. Role of higher education institutions in the implementation of sustainable development goals. In Sustainable Development Goals and Institutions of Higher Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, Y.; Li, S.; Ahmad, W.; Maodaa, S.N.; Sayed, S.R.M.; Gan, J. Advancements in technology and innovation for sustainable agriculture: Understanding and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyimah, P.; Appiah, K.O.; Appiagyei, K. Seven years of United Nations’ sustainable development goals in Africa: A bibliometric and systematic methodological review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 395, 136422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.; Shane, S.A.; Herold, D.M. Rumors of the death of dispositional research are vastly exaggerated. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Su, Y.; Qi, M.; Chen, J.; Tang, J. A multilevel model of entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: Opportunity recognition as a mediator and entrepreneurial learning as a moderator. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 837388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Park, M.J. Entrepreneurial education program motivations in shaping engineering students’ entrepreneurial intention: The mediating effect of assimilation and accommodation. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 11, 328–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhead, P.; Ucbasaran, D.; Wright, M. Experience and cognition: Do novice, serial and portfolio entrepreneurs differ? Int. Small Bus. J. 2005, 23, 72–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.S.; Shepherd, D.A. Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, H.; Shepherd, D.A. Recognizing opportunities for sustainable development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr. What lies beneath? The experiential essence of entrepreneurial thinking. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, A.C. Experiential learning within the process of opportunity identification and exploitation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, D.A.; Barr, P.S.; Shepherd, D.A. Cognitive processes of opportunity recognition: The role of structural alignment. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N., Jr.; Dickson, P.R. How believing in ourselves increases risk taking: Perceived self-efficacy and opportunity recognition. Decis. Sci. 1994, 25, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Saleem, I.; Anwar, I.; Hussain, S.A. Entrepreneurial intention of Indian university students: The role of opportunity recognition and entrepreneurship education. Educ. + Train. 2020, 62, 843–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Rodriguez, A.R.; Medina-Garrido, J.A.; Lorenzo-Gómez, J.D.; Ruiz-Navarro, J. What you know or who you know? The role of intellectual and social capital in opportunity recognition. Int. Small Bus. J. 2010, 28, 566–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhave, M.P. A process model of entrepreneurial venture creation. J. Bus. Ventur. 1994, 9, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouarir, H.; Diani, A.; Boubker, O.; Rharzouz, J. Key determinants of women’s entrepreneurial intention and behavior: The role of business opportunity recognition and need for achievement. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, L.; Yli-Renko, H. The impact of environment and entrepreneurial perceptions on venture-creation efforts: Bridging the discovery and creation views of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 833–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship; University of Illinois: Champaign, IL, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Nature and operation of attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, P. A cognitive map of sustainable decision-making in entrepreneurship: A configurational approach. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 24, 787–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peráček, T.; Kaššaj, M. A critical analysis of the rights and obligations of the manager of a limited liability company: Managerial legislative basis. Laws 2023, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Rueda-Cantuche, J.M. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.E.; Polemis, M.L. Does financial development affect environmental degradation? Evidence from the OECD countries. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1162–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redclift, M. The meaning of sustainable development. Geoforum 1992, 23, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A.A.; Kates, R.W.; Parris, T.M. Sustainability values, attitudes, and behaviors: A review of multinational and global trends. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 413–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardoyo, C.; Narmaditya, B.S.; Handayati, P.; Fauzan, S.; Prayitno, P.H.; Sahid, S.; Wibowo, A. Determinant factors of entrepreneurial ideation among university students: A systematic literature review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonesso, S.; Gerli, F.; Pizzi, C.; Cortellazzo, L. Students’ entrepreneurial intentions: The role of prior learning experiences and emotional, social, and cognitive competencies. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2018, 56, 215–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, S.D.; Bechara, A.; Damasio, H.; Grabowski, T.J.; Stansfield, R.B.; Mehta, S.; Damasio, A.R. The neural substrates of cognitive empathy. Soc. Neurosci. 2007, 2, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiles, T.H.; Tuggle, C.S.; McMullen, J.S.; Bierman, L.; Greening, D.W. Dynamic creation: Extending the radical Austrian approach to entrepreneurship. Organ. Stud. 2010, 31, 7–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Noboa, E. Social entrepreneurship: How intentions to create a social venture are formed. In Social Entrepreneurship; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2006; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.H. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat. Sel. Doc. Psychol. 1980, 10, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Q.; Robertson, J.L. How and when does perceived CSR affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? J. Bus. Ethic 2019, 155, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and Content Analysis of Oral and Written Materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Methodology; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, G.N.; Hanks, S.H. Founder competence, the environment, and venture performance. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelken, H.N.; de Jong, G. The impact of values and future orientation on intention formation within sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 122052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, J.M.; Rauch, A.; Frese, M.; Rosenbusch, N. Human capital and entrepreneurial success: A meta-analytical review. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Akhtar, S.; Qureshi, N.A.; Iqbal, S. Predictors of entrepreneurial intentions: The role of prior business experience, opportunity recognition, and entrepreneurial education. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 882159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Agu, A.G. A survey of business and science students’ intentions to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship. Small Enterp. Res. 2021, 28, 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, L.C. Identification, intentions and entrepreneurial opportunities: An integrative process model. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2016, 22, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nițu-Antonie, R.D.; Feder, E.S.; Stamenovic, K.; Brudan, A. A moderated serial–parallel mediation model of sustainable entrepreneurial intention of youth with higher education studies in Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keh, H.T.; Der Foo, M.; Lim, B.C. Opportunity evaluation under risky conditions: The cognitive processes of entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 27, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Chen, B.; Chen, H. Time lag effect” and evaluation of entrepreneurial education effect in entrepreneurship education. Innov. Entrep. Educ. 2010, 1, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).