Abstract

Entrepreneurial education is an established phenomenon that enhances entrepreneurship, which is critical for economic sustainability. The study investigated converting entrepreneurial education into entrepreneurial intentions in graduating university students. It was expected that entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurial alertness play a significant role in this process. A questionnaire was developed, and data was collected from students either graduating or in their last year of undergraduate studies. Regression analysis using AMOS was conducted to test the relationships among study variables. Results indicate that entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurial alertness have mediating roles in the process separately. Entrepreneurial alertness is the most significant mediator in converting the effect of entrepreneurship education into entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurial mindset also partially mediates the effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions. The findings of this study are essential for educational planners and organizations in the entrepreneurial ecosystem to evaluate the effectiveness of entrepreneurial education in training programs. Future studies may consider replicating this study in different physical and cultural settings.

1. Introduction

The creation and performance of business ventures have a significant impact on the economic development of regions and countries because they produce innovation, jobs, and income [1,2,3]. Entrepreneurship and the blossoming of entrepreneurial ventures is also essential for economic sustainability, with ramifications for environmental sustainability as well. However, business ventures vary in their contribution to economic development, depending on their characteristics and potential [1,2,3]. Therefore, it is essential to examine the factors that influence the emergence and success of different kinds of business ventures and how they affect the economic, social, and environmental welfare of societies.

Entrepreneurship is a vital skill for students in the twenty-first century, enabling them to create value, solve problems, and adapt to changing environments. According to a global survey of more than 267,000 students from 58 countries, almost 18% intend to start their own business within five years after graduation, and 9% are already involved in entrepreneurial activities [4]. Therefore, universities should support and facilitate student entrepreneurship by offering relevant courses, facilities, and incentives [5]. Google, Microsoft, and Facebook are among the most valuable global companies, and they all have something in common: they were founded by students. Google’s co-founders met at Stanford, Microsoft’s Bill Gates left Harvard College to pursue his vision, and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg created the social network from his Harvard dorm room [6].

The study was conducted in Pakistan for several compelling reasons. Pakistan offers a unique context with a rapidly growing youth population, where 65% of the population is under the age of 25 [7]. This demographic trend provides an important opportunity for economic development through entrepreneurship. However, the country also faces challenges such as high graduate unemployment, estimated at 28% [8], and the need for more effective educational methods to equip students with business skills. Previous studies have highlighted the potential for entrepreneurial education (EE) to solve these problems by promoting entrepreneurial mindset (EM) and entrepreneurial alertness (EA) among students. Focusing on Pakistan, this study aims to provide insights into local contexts that can help improve educational practices and help economic development through entrepreneurship. Motives for choosing Pakistan include addressing the high unemployment rate among graduates, leveraging the youth population for economic growth, and responding to calls for more contextual research in business education.

EE is a policy instrument to promote business venturing and stimulate entrepreneurial intentions (EI) among individuals [9]. However, the observed evidence on the effectiveness of EE on business venturing is inconclusive, with previous studies finding inconsistent and contradictory results [6]. Therefore, there is a need for more rigorous and comprehensive research on the impact of EE on business venturing, considering the contextual and individual factors that may affect this relationship. EE has received substantial attention from scholars, with college students needing the courage to start businesses for themselves or create jobs for others. The purpose of providing EE in academia is to encourage students to start their ventures and enhance their creativity and innovation skills [10]. Wang et al. [11], found EE has an impact on students’ EM and creativity, which enables them to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities. Furthermore, a study by Baron, ref. [12] recognized the importance of EA in starting entrepreneurial activities with influential social and economic impression. These studies indicate that EE, EM, and EA can enhance the EI of individuals and equip them for future entrepreneurial ventures.

The study separates itself by focusing on the mediating roles of EM and EA in the relationship between EE and EI, which has not been extensively researched in previous studies. While many studies have examined the direct impact of EE on business outcomes, this study aims to provide a more important understanding by investigating how EM and EA affect this relationship. The collaboration of this study involves presenting a comprehensive model that integrates these mediating factors, thereby filling a significant gap in the literature. The motivations behind this study are to increase the effectiveness of EE programs by identifying key mediators that can increase their impact on EI. By carrying out this study, the authors aim to provide actionable insights for teachers and policymakers to design more effective EE programs that develop business skills and intentions in students.

Thus, this study aims to explore the effects of EE on EI and examine the mediating effect of EM and EA on this relationship in graduate students. This study approach fills the gap in the literature by examining the relationship between EA and EE and responds to the calls for more research on the effects of EE [13]. Saadat et al. [14] investigated how EE and EM are related through the mediation of EA and suggested further research on other vital factors, such as EI. The literature has not sufficiently explored how EA and EM mediate the effect of EE on EI, and the relationship has not been adequately addressed [15]. By exploring how EE influences EI, educational practices can be improved to ensure that students who complete entrepreneurship programs can identify entrepreneurial opportunities—essential for supporting new venture creation. This study proposes a conceptual model of how EE can directly affect EI, and how EA and EM mediate the relationship between EE and EI.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Entrepreneurship Education (EE)

EE is explained as any pedagogical process of education for delivering entrepreneurial approaches and expertise. EE aims to help students increase their chances of succeeding in their businesses and broaden their career options [13,16]. The previous literature categorized EE into three kinds of frameworks: instruction about entrepreneurship, instruction for entrepreneurship, and instruction through entrepreneurship [17]. The first type focuses on theoretical views of entrepreneurship, such as the concepts, principles, and models of starting, running, and managing a business. The goal is to offer students entrepreneurial knowledge and help them learn the consequences of entrepreneurial actions [18]. The second type emphasizes the practical considerations of entrepreneurship, for example the steps and skills required to establish and operate an entrepreneurial venture. The purpose is to teach the practical skills and knowledge to students that they need to start businesses [17]. This type of training is mainly connected to active and practical methods to inspire learners to be enthusiastic about entrepreneurship, seek out market knowledge, and identify more influential opportunities for entrepreneurship.

The third type is related to training for existing entrepreneurs who want to learn specific skills, such as how to market and sell their products, how to plan and execute their strategies, and how to advance and promote new products, with the goal being to help them grow and sustain their businesses. This approach is suitable for both experienced and learner entrepreneurs who want to learn how to start and run their businesses [18]. Hoang et al. [9], identified that there are three elements of EE in Vietnam: academic programs that teach entrepreneurship, non-academic programs that support entrepreneurship, and social education that encourages start-up intentions. However, the experimental evidence on the effectiveness of EE on business venturing is inconclusive, with previous studies producing inconsistent and contradictory findings [6]. More research is needed to examine how EE affects business venturing, considering the contextual and individual factors that may shape this relationship.

2.2. Entrepreneurial Intentions (EI)

EI is the cognitive state that leads and motivates entrepreneurial actions, such as starting a new venture or pursuing an entrepreneurial opportunity [19]. EI is a crucial construct in entrepreneurship research because it helps explain and predict the emergence and performance of entrepreneurial activities [20]. However, EI is also a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, influenced by various individual and contextual issues, for instance personality traits, attitudes, skills, education, culture, environment, and policies [21]. Therefore, understanding the antecedents and effects of EI is a significant challenge and opportunity for entrepreneurship scholars and practitioners.

Huang et al. [22], investigated the effect of entrepreneurship policy on college students’ EI in China and found that entrepreneurial practice and entrepreneurial spirit were mediators between policy and EI. Esfandiar et al. [23], developed a new version of the integrated model of EI and tested it with students in the field of tourism in Iran. Self-efficacy, feasibility, opportunity, attitude, and collective efficacy remained the main factors that influenced EI. A general model of EI that covers three main motivations for entrepreneurial behavior—profit, social impact, and innovation—was proposed by [21]. They tested their model with Australian university students and found that different mixes of factors led to different kinds of entrepreneurs.

2.3. Entrepreneurial Alertness (EA)

EA is the skill to notice and recognize entrepreneurial openings and opportunities that are not obvious or widely known [24]. EA is a critical concept in entrepreneurship research because it helps explain and predict the emergence and performance of entrepreneurial activities [25]. However, EA is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, influenced by various factors, such as cognitive processes, personality characteristics, knowledge, experience, social networks, environment, and policies. There are five perspectives on EA: market process, individual decision, dynamic capability, entrepreneurial orientation, and entrepreneurial cognition [26].

EA is an element of the market process that helps entrepreneurs find and exploit market gaps [27,28]. EA is also understood as a perceptual variable that affects a person’s choice to become an entrepreneur by influencing their opportunity recognition and evaluation [12,25]. EA is also a dynamic capability that enables entrepreneurs and employees to adapt to changing environments and create value [29]. EA is also understood as a dimension of entrepreneurial orientation that reflects the individuals’ tendency to identify and pursue new opportunities [30,31]. EA is also a cognitive process involving attention, pattern recognition, and information processing [32,33].

2.4. Entrepreneurial Mindset (EM)

EM has been defined as the skills to quickly identify, act, and move in highly uncertain circumstances [34]. EM is the ability to respond and decide on an opportunity when uncertainty exists [35]. McMullen and Kier, 2016 [36], explained EM as the ability to spot and use opportunities for using available resources. Consequently, entrepreneurs may face risks when they pursue their ventures. According to Cui et al. [37], the EM is an approach to thinking or the ability to use opportunities under uncertain conditions. Yadav and Bansal [38] suggest that an EM is also a method of viewing marketing through an entrepreneurial lens, which involves identifying customer needs, creating value propositions, developing innovative solutions, and leveraging resources. Daspit et al. [39], suggested EM as a multidimensional construct including cognitive, affective, and behavioral components.

2.5. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis

Stimulus Organism Response Theory

According to the stimulus organism response theory (SOR), developed by Mehrabian and Russell, ref. [40] in environmental psychology, human behavior can be explained by a sequential process. The SOR theory of Mehrabian and Russell, 1974 [40], explains how external environmental cues (S) affect how people think and feel inside (O), which then influences how they act or behave. The SOR model explains how people’s thoughts, emotions, and feelings are influenced by their environment and how this affects their actions and behaviors [15]. We use the SOR paradigm to build our conceptual framework. We define environmental cues (S) as stimuli that affect the emotional and cognitive states (organisms) of university students [41]. Environmental stimuli, such as EE, curriculum, and lecturer competency, help students learn the knowledge, skills, and cognitive processes of entrepreneurship [42].

In our conceptual model, we define these three factors related to education as environmental stimuli. The organism (O) is an individual’s cognitive and emotional state, activated when perceiving environmental stimuli. Individuals process these environmental stimuli and use their thinking and feeling abilities to select and store relevant information before reacting to them [15]. Four psychological constructs from the model of Mair and Noboa [43] are used as organisms in this study. Education-related stimuli influence these organisms first, which then leads to behavioral responses. The outcomes that individuals have from organisms are called behavioral responses [44]. Behavioral intentions and actual behaviors are the types of behavioral responses that individuals have [45].

2.6. Entrepreneurship Education and Entrepreneurship Intentions

By providing students with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities, EE can affect EI [46]. However, EE should also consider the contextual factors that may influence students’ EI, such as the institutional environment, industry characteristics, social networks, and cultural values [26]. EE should adopt a holistic and integrative approach combining cognitive and experiential learning methods to align with the specific needs and expectations of the students and society [28]. The willingness and readiness of individuals to start a new venture are reflected by their EI—a critical determinant of entrepreneurial behavior [47]. However, EI is not a fixed or innate trait but rather a dynamic and learnable outcome that can be influenced by various factors, such as entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, entrepreneurial attitude, entrepreneurial motivation, and entrepreneurial experience [48].

External stimuli, such as market signals, customer feedback, technological changes, and competitive actions, can influence EI [49]. Therefore, EI should be considered a multifaceted and context-dependent construct that requires constant attention and adaptation from individuals. By exposing students to real-world problems and challenges that require innovative solutions, EE can foster EI [49]. EE can also enhance students’ learning outcomes and self-confidence by providing feedback, reflection, and collaboration opportunities to stimulate their EI [46]. EE can also incorporate race-conscious pedagogy to address the systemic barriers and challenges faced by students of color and provide them with relevant support and resources to develop their EI [50]. EE aims to equip students with the skills, knowledge and mindset necessary to start and manage their businesses. It fosters creativity, innovation, and problem-solving abilities, which are critical to business success. Business intentions (EI) refer to the individual’s motivation and commitment to engage in business activities. Thus, we suggest the following hypothesis:

H1:

EE has a positive effect on EI.

2.7. Entrepreneurship Education and Entrepreneurship Alertness

One factor that affects a person’s EA is their educational experiences [51]. According to Pirhadi et al. [46], students can improve their EA by developing their entrepreneurial skills and character, which help them assess the desirability and feasibility of entrepreneurial opportunities. Vecchiarini et al. [49], explored the role of experiential learning in an online setting for EE. They found that it improved students’ EM and alertness by offering them authentic tasks, feedback, reflection, and collaboration. Monroe-White and McGee [50] examined the impact of race-conscious EE on students of color. They found that it increased their EM and alertness by addressing their systemic barriers and challenges and providing them with relevant support and resources. EE aims to equip students with the skills, knowledge, and mindset necessary to identify and pursue business opportunities. Entrepreneurial alertness (EA) refers to the ability to take notice and act on these opportunities. EE improves EA by providing experiential learning, feedback, and support, which helps students develop the skills and mindset needed to evaluate the desire and feasibility of business projects. On the basis of the above literature, we can hypothesize the following:

H2:

EE has a positive effect on EA.

2.8. Entrepreneurship Education and Entrepreneurship Mindset

An individual’s educational experiences are one factor that affects their EM [49]. Cui et al. [37] further investigated the relationship between these concepts and found that EE positively affected EM and inspired students’ entrepreneurial aspirations. Vecchiarini et al. [49], studied the role of experiential learning in an online setting for EE. They found that it improved students’ EM and alertness by offering them authentic tasks, feedback, reflection, and collaboration. Thus, we suggest the following hypothesis;

H3:

EE has a positive effect on EM.

2.9. Entrepreneurship Mindset and Entrepreneurship Intentions

One critical factor that influences EI is EM: the self-acknowledged desire to start a new career. EM refers to the thinking and behavior that enables one to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities successfully. Several empirical studies have confirmed the positive relationship between EM and EI and the role of other factors that affect them. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy is enhanced by EE, mindset, and creativity, which positively and significantly affect EI [22]. The relationship between EE and culture and students’ EI is strengthened by the EM [52]. The intention to become self-employed among school students in South Africa was positively influenced by the EM [53]. Developing and maintaining an EM requires regular practice over time [54]. Individuals must be more attentive to the opportunities that arise [55]. We hypothesize that individuals with EMs are more likely to engage in entrepreneurial activities than those without EMs. Business mindset (EM) refers to attitudes, skills, and behaviors that enable individuals to identify and capitalize on opportunities, overcome challenges, and persist while facing setbacks. Business intent (EI) is a factor that drives an individual’s decision to pursue business activities. EM positively affects EI by promoting an active, opportunity-focused, and flexible approach to business.

H4:

EM has a positive effect on EI.

H5:

EM mediates the relationship between EE and EI.

2.10. Entrepreneurship Alertness and Entrepreneurship Intentions

One of the critical cognitive factors that influence EI is EA: the self-acknowledged conviction to start a new venture in the future. EA refers to noticing and acting on profitable opportunities that others may overlook or ignore. According to several empirical studies, EA and EI have a positive relationship and other entrepreneurial outcomes. Lu and Wang [56] found that individuals who intend to start a business can enhance their opportunity recognition and judgment by developing their EA. Van Gelderen et al. [57], suggested that EA can increase the motivation and confidence of people to transform their ideas into new ventures, especially for extroverted individuals who are more sociable and outgoing. Araujo et al. [58] conducted a meta-analysis of 125 studies and found a significant positive correlation (1) between alertness and EI and (2) between innovation, opportunity recognition, and performance. EA refers to the ability to focus on and act on profitable opportunities that others may ignore. Business intent (EI) is the factor that drives an individual’s decision to pursue business activities. EA positively affects EI by increasing the confidence to identify opportunities, make decisions, and turn ideas into new projects.

H6:

EA has a positive effect on EI.

H7:

EA mediates the relationship between EE and EI.

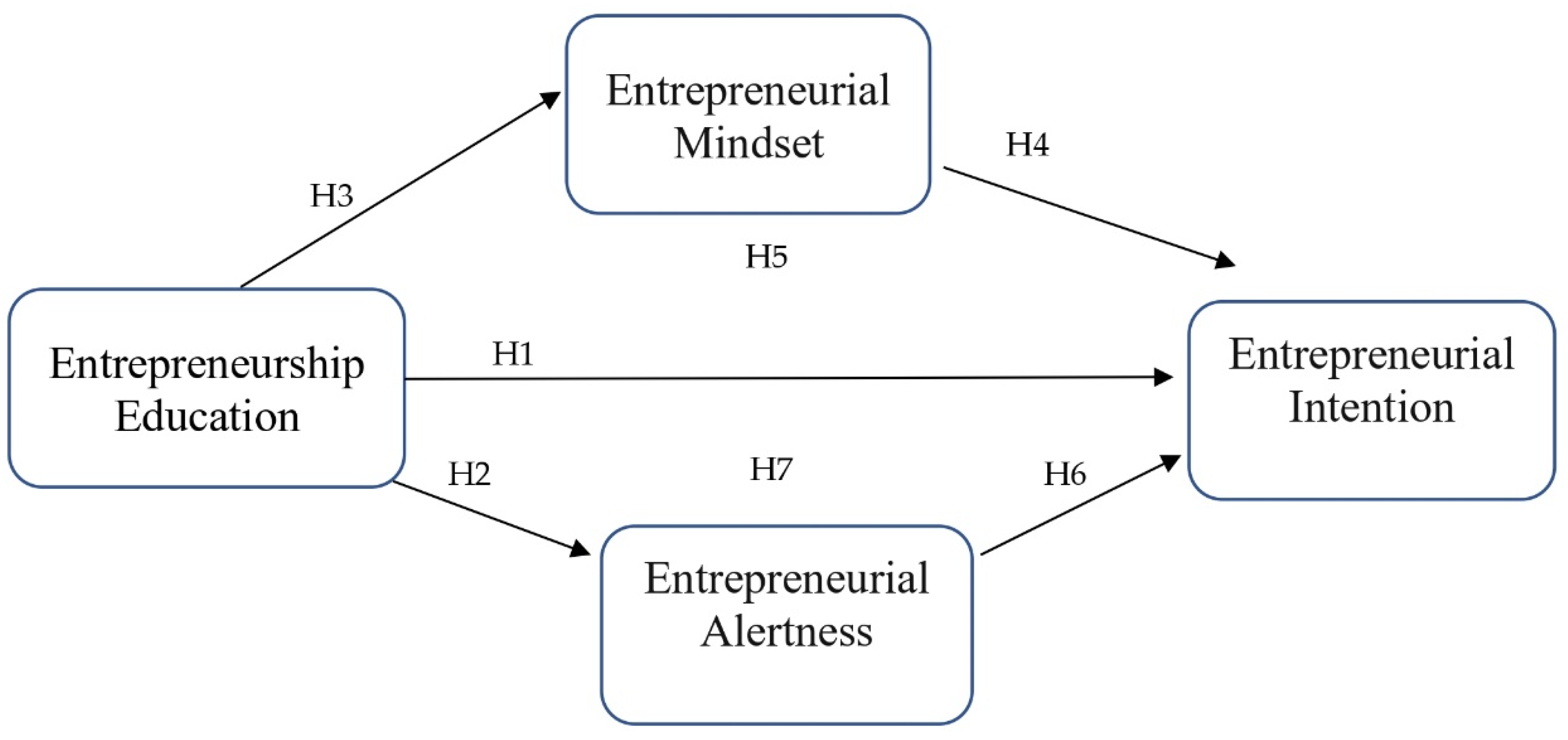

Figure 1 shows the direct and indirect relationships of the variables. EE had direct positive relationship with EI (H1). EE has a direct positive relationship with EA (H2) and EM (H3). EM (H5) and EA (H7) mediates the relationship EE and EI.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Population and Sample

The population of this study consists of students who were about to graduate or were in the final year of their respective undergraduate degree programs. The universities were selected using the convenience sampling technique. We selected state-owned government universities located in Islamabad and Rawalpindi. In total, 300 printed questionnaires were given to the respondents, who were asked to complete them according to their entrepreneurship intentions. In the response, we received 272 questionnaires, of which 261 were found to be valid and used for the analysis.

The target population of senior undergraduates is particularly relevant for studying EI because they are at a critical juncture where they are making career decisions, including the possibility of starting their own businesses. Facility sampling was used because of management’s consent to facilitate ease of access to these universities and distribution of questionnaires. This method is practical for research studies where the main goal is to gather early insights rather than generalize results for a large population. Public universities in Islamabad and Rawalpindi offer a wide range of educational programs. This diversity ensures that the sample includes students from different fields, providing a holistic view of business intentions in different areas of study.

Sample size is consistent with similar studies in the field of business education and intentions, providing the basis for the comparison and validation of results. For example, Alshebami, ref. [59] also used sufficient sample sizes to ensure the reliability of their results. Table 1 provides background information of the participants. Among the participants, 189 were 21–25 years (72.41%), 72 were 25–28 years (27.59%), 152 participants were male (58.24%), and 109 were female (41.76%). In terms of academic disciplines, 112 participants (42.91%) were studying social sciences, 92 participants (35.25%) were studying natural sciences, and 57 participants (21.84%) were studying management sciences. The families of participants were from business (27.59%), public jobs (19.54%), private jobs (17.24), farming (24.90), and others (10.73%). In terms of residence, 151 participants lived in rural areas (57.85%), while 110 lived in urban areas (42.15%).

Table 1.

Demographic information.

3.2. Measures and Analytical Approach

The questionnaire in this study was adopted from previous studies and revised to measure variables such as entrepreneurship education, EM, EA, and EI. A 5-point Likert scale was used to measure these variables (1 means strongly disagree, and 5 means strongly agree). The EI was measured with six questions from Linan and Chen [60], and EE was measured with four questions from [6]. EA was measured through a scale developed by Tang et al. [25], and EM was measured through a scale developed by Cui et al. [37]. All the scales used in this study were in English and considered understandable to university students.

The results were analyzed using SPSS 28.0 and AMOS 22. Aggregated values of all scales were used to create a universal variable for each variable. AMOS was used to perform structure equation modelling.

3.3. Reliability and Validity

The reliability and validity of all constructs were checked before formal analysis. Table 2 shows the mean, standard deviation, correlations between the variables, and Cronbach’s alpha. All the mean values for variables are above 3.5, suggesting that most of the responses agree with the items. EI has the highest mean value, indicating that a larger number of respondents indicate an intention to involve themselves in entrepreneurship. The standard deviation values are also high, particularly for EE, indicating a stronger change in opinion in the scale measures. The correlations of all the variables are significant at the 95% confidence level. All the values are within acceptable ranges and suggest significant correlations between the variables. The VIF values are below 3, which is lower than 5, meaning no multicollinearity between the variables. The values given in bold diagonally represent the Cronbach alpha values of reliability. All of the values are above the threshold of 0.7. For measuring the common method bias, the Harman one-factor test was used. The total variance extracted is 41.2% which is within the acceptable level of 50%.

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviation, correlations, and Cronbach’s alpha.

For identifying the latent variable reliability, the CR is at least 0.7, MSV is less than CR, and the MaxR (H) is greater than CR [60]. The values of all variables are given in Table 3. All the CR values exceed 0.7, except for EE. The MSV values of all the variables are less than CR, except for EE, which is slightly higher than the CR value. The MaxR (H) value for all the variables is greater than the CR values. In the given context, all the variables have acceptable latent variable reliability. The AVE is at least 0.5. The AVE values of EM, EE, and EI are in the acceptable range. The value of EA is on the lower side. However, in the given context, it is considered for further analysis because the level of alertness in graduating students may not be on the higher side when EE is not organized.

Table 3.

Validity of constructs.

The principles of Fornell and Larcker [61], were used to identify the convergent validity with the assumption of divergent validity of the measurement model. We compared the squared AVE values of each latent variable against their inter-construct with other latent variables. We assumed divergent validity if the squared AVE value was greater than below off-diagonal values (correlation coefficients). Bold diagonal values in Table 3 are slightly greater than off-diagonal values; therefore, the model matches with the assumption of divergence [61].

For discriminant validity, the MSV values should be less than AVE [62]. The MSV values of all the given variables are greater than AVE, which indicates some issues with discriminant validity. Another test of discriminant validity, the HTMT test, was used. The values given in Table 4 indicate the HTMT for the variables. Threshold values for strict and liberal discriminant validity are 0.850 and 0.900, respectively. All the values are below 0.9, so liberal discriminant validity is ascertained for all the variables. The core reason for not obtaining strict discriminant validity is that the scale developed is from studies conducted in contextual settings where entrepreneurship programs are not well established and there is not enough guidance given to students who want to move in that direction. There are also well-established business incubation facilities and guidance. In the current context of this study, several courses have been added to the programs, and a few seminars have been conducted. However, there are no specialized programs to encourage entrepreneurship. Despite the constructs being adapted, they were not able to calculate the strict discriminant validity of the associated scales. Consequently, the researchers conducted the SEM of EM and EA using separate models.

Table 4.

HTMT analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Hypothesis Testing

The hypotheses developed were tested through linear regression using AMOS. The results show strong direct relationship between EE and EI, depicted by beta value (0.598) and R-square value (0.357), as shown in Table 2, confirming our first hypothesis, H1. Similarly, EE substantially impacts EA (Beta value 0.645, R-square 0.416) and entrepreneurial motivation (Beta value 0.753, R-square 0.567), validating hypotheses H2 and H3.

Furthermore, Table 5 shows a strong relationship between EA and EI. Similarly, entrepreneurial motivation also has a strong effect on EI. These results indicate a robust cause-and-effect relationship, validating H4 and H6.

Table 5.

Direct effects.

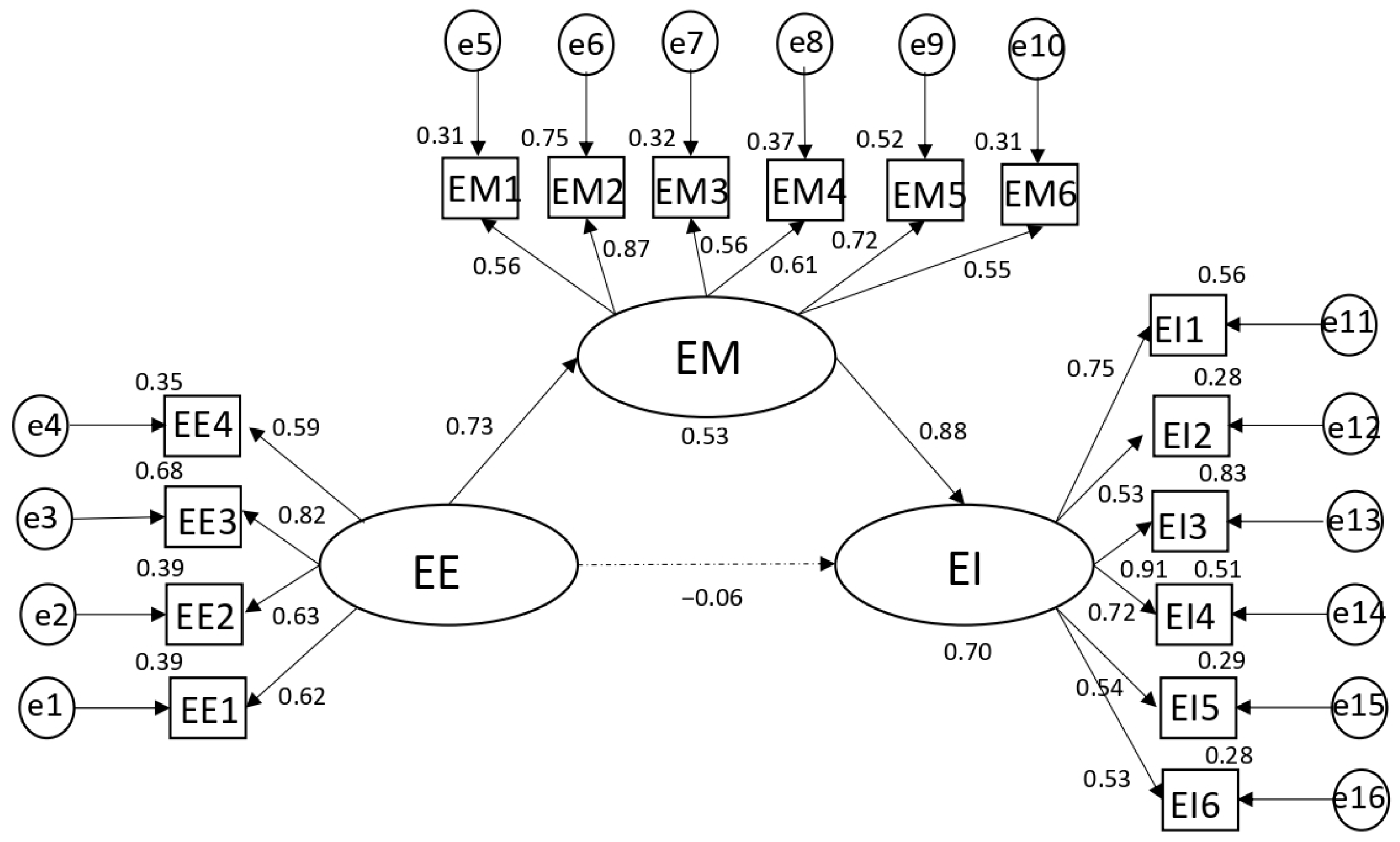

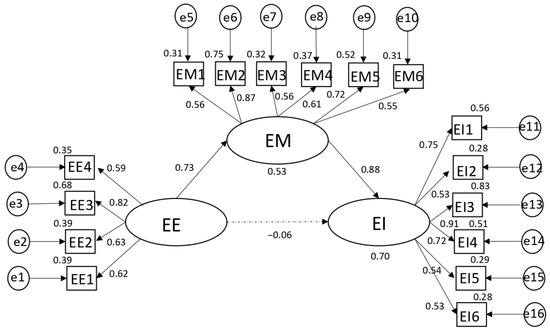

The complete conceptual model was mapped to test H5 and H7 (Figure 2). The results of the model suggested that EE did not affect EI. Further analysis was conducted by creating separate mediation models for EM and EA, as decided at the validity testing level.

Figure 2.

Mediation of EM.

4.2. Mediation of EM and EA

Table 6 and Figure 2 represent the effects of the EM and EA mediation model between EE and EI. The beta value of the relation between EE and EM is −0.73, which is significant. The R-square value of EM is 0.53, which suggests that EE explains 53% of the variation in EM. The beta value of the link between EM and EI is 0.88, suggesting a higher effect of EM on EI (induced by EE), given that the direct effect of EM on EI was 0.81. The R-square value of EI is 0.70, which shows the model explains 70% of the variation in EI. In terms of factor loading in Figure 2, some items were low (EI6; EM6; EM7; EM11). According to Hair et al. [62], items with low loadings can be retained if they are theoretically justified and contribute to the overall model fit. Therefore, the values are in acceptable ranges. In contrast, the model fit values of the complete model, which, after deleting the insignificant direct effects, were lower than the acceptable ranges. The CMIN/DF value is 1.6, within an acceptable range. The CFI and IFI values are 0.90 and 0.92, but the TLI and RFI values are below 0.9. The RMSEA value is also 0.09, above the threshold value of 0.08. Consequently, the researchers suggest partial acceptance of H5.

Table 6.

Hypothesis testing—2.

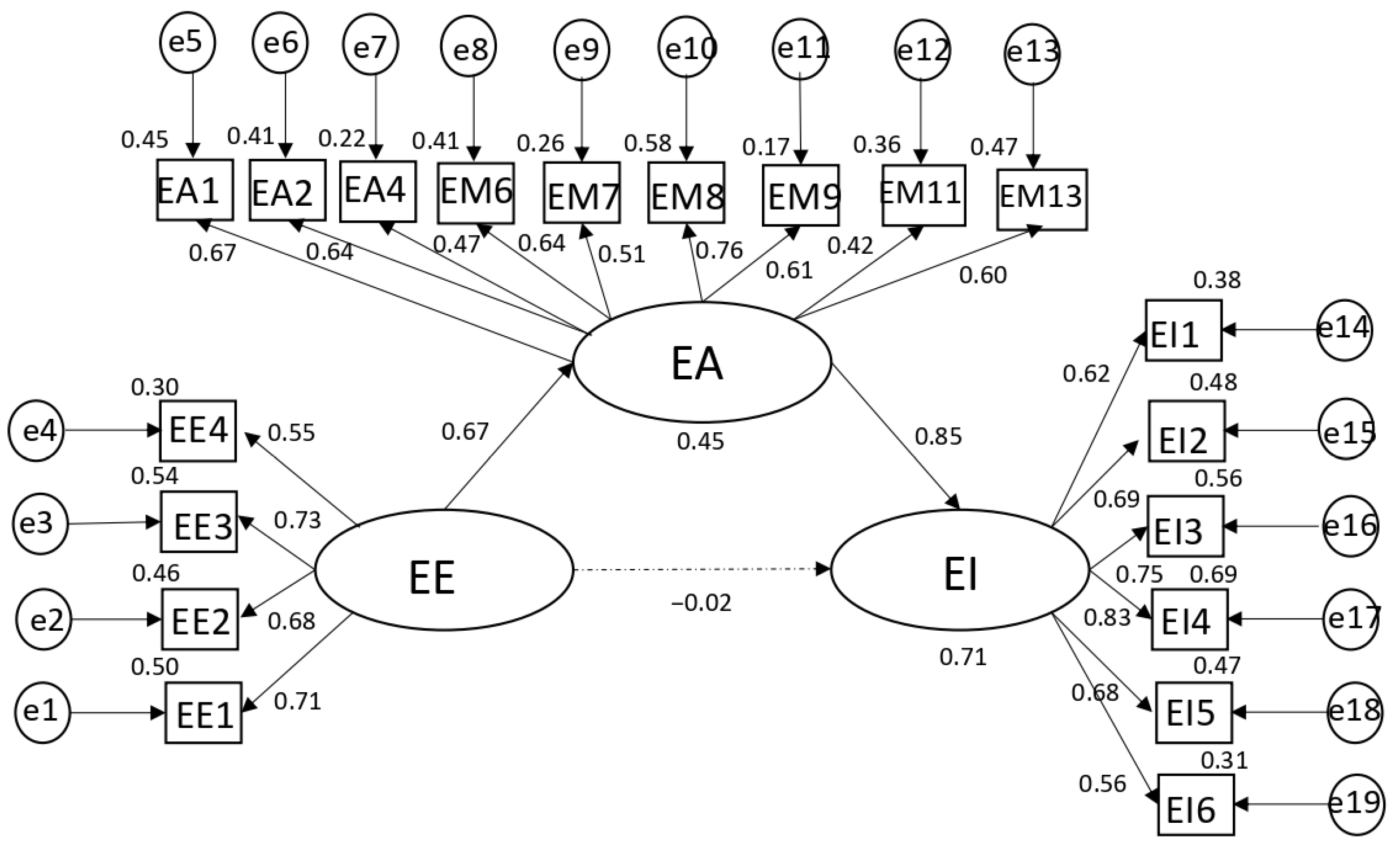

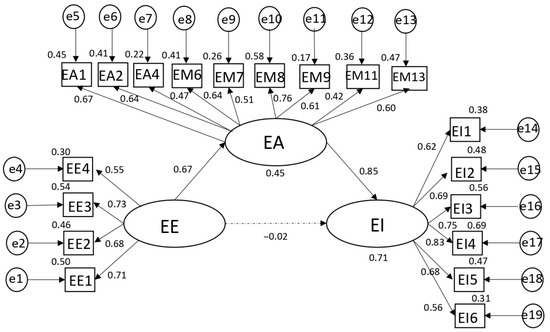

Table 6 and Figure 3 also represent the effects of the mediation model of EA between EE and EI. The beta value of the direct relation between EE and EI in the presence of EA is −0.02, which is insignificant. The beta value of the relation between EE and EA is 0.59, which is significant. The R-square value of EA is 0.35, suggesting that 35% of the variation in EM is explained by EM. The beta value of the link between EA and EI is 0.85, suggesting that EA induced by EE has a higher effect on EI, given that the direct effect of EM on EI was 0.81. The R-square value of EI is 0.70, which indicates that the model explains 70% of the variation in EI. Therefore, the values are in acceptable ranges. Supporting the given results, the model fit values of the complete model are in the acceptable ranges. The CMIN/DF value is 1.3, within an acceptable range. CFI and IFI values are both 0.90, but the TLI and RFI values are below 0.90. The RMSEA value is 0.07, lower than the threshold value of 0.08. Consequently, we suggest acceptance of H7, as most of the model fit values are in acceptable ranges.

Figure 3.

Mediation of EA.

5. Discussion

This article is aimed at examining EE and how this converts into actual entrepreneurship among university students. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the effects of EM and EA in converting EE to EI among graduating students, particularly in developing countries like Pakistan.

EE has a major effect on EI, as indicated by the results of this study. This is in line with [26,46,48]. An EE is also a critical antecedent to EM and EA. These results are similar to [37,47,50,51]. These results also match the logic that education develops a mindset and increases alertness in students. Therefore, an education focused on any aspect of entrepreneurship will create a certain mindset and alertness toward entrepreneurship.

In the presence of an EM, the effect of EE on EI becomes insignificant, suggesting a strong mediation effect of an EM. Although the model fit was not achieved, the results are strong enough to arrive at this conclusion. Even in logical and theoretical terms, education creates a mindset that is further manifested in the form of intentions and actions, consistent with the opinion of [50]. Similarly, EA also has a powerful mediating effect between EE and EI. Education is the stimulus that creates alertness, eventually leading to the development of an intention. In line with this logic developed using the SOR paradigm, EE will create alertness toward entrepreneurial opportunities, leading to an intention to indulge in entrepreneurship.

6. Implications

Although there are no entrepreneurial-focused programs in the universities in this study other than some courses, seminars, and workshops in the degree programs, the intention of the students toward entrepreneurship is evident, illustrating an increasing EM. Even a small level of guidance and direction increase their alertness to entrepreneurial opportunities. Consequently, universities and other learning institutions should design their entrepreneurship programs so students become alert and accustomed to picking up entrepreneurial cues from their environment.

From the theoretical perspective, it is essential to identify variables that function as stimuli to increase students’ alertness to entrepreneurial opportunities. The Giessen–Amsterdam model by Rauch and Frese [63] can also be used to explore elements of personality that can enhance alertness to entrepreneurial cues from the environment.

While there are no dedicated programs for business focus at the universities in the study, several courses, seminars, and workshops within the degree programs indicate an increased interest in entrepreneurship among students. This interest is reflected in a growing EM among students. Even minimal guidance and direction can increase their vigilance towards business opportunities. Consequently, universities and other educational institutions should develop comprehensive entrepreneurship programs that enable students to be more in tune with business indicators in their environment. The debate should go deeper into the implications for academics and policymakers in entrepreneurship education. Effective business programs should focus not only on providing knowledge, but also on the development of student EM and EA. This can be achieved through experiential learning, mentoring, and providing opportunities to solve real-world problems. Furthermore, incorporating knowledge of pedagogy with regard to race can remove systemic barriers faced by students of color, ensuring that they receive the necessary support and resources to develop their business intentions.

7. Conclusions

New business ventures are the lifeblood of an economy. In every vibrant economy, entrepreneurship carries the significant weight of providing employment, which leads to economic sustainability and contributes towards environmental sustainability as well. Consequently, many countries have tasked universities with developing programs and infrastructure to encourage entrepreneurship. Many universities provide generic inputs in their programs or provide specific programs to foster entrepreneurship. With the information revolution, the trend of indulging in entrepreneurship is increasing, particularly among students graduating from higher educational programs. This study focused on empirically investigating the role of EE in generating EI in graduating students.

The literature review suggested that EA and EM are two key variables discussed among researchers that are critical in converting EE into EI. An empirical model was developed with these variables based on the logic of the SOR paradigm. The findings indicate a strong mediating role of EM and EA in converting education into EI. Alertness is more significant because, with its effects, even mindset becomes insignificant. If an EE creates an effect in a student in which the student becomes alert to entrepreneurial opportunities, there is a very high chance that EI will be created. Higher EI would lead to increased economic activity, enhancing economic sustainability.

8. Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations regarding its scope. The graduating students at several universities were the sample. There were also resource and time limitations. The developed model is theoretically sound, and it may be replicated across different physical and cultural settings. Some more contextualization of the adapted scale may also enhance the effectiveness of future studies. This study employed a convenience sampling technique, selecting universities in the capital city of Islamabad due to its diverse representation of the country’s population. Reliance on convenience sampling cannot fully capture the heterogeneity of the entire student population across Pakistan. To enhance the generalizability of future studies, it is recommended to use different sampling techniques, such as stratified random sampling or cluster sampling. The scale of EE, in particular, should be developed further. Future studies may consider replicating this study in varying contexts to consolidate its findings. Outcome variables for the effect of education, such as actual entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial performance, may be used in future studies. Other intermediate variables between education and intention, like personality, may also be researched in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.A., M.Z.b.A.R. and M.H.; methodology, I.M.Q. and M.H.; software analysis, I.M.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.Q. and M.H.; writing—review and editing, M.A.A. and M.Z.b.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the International Islamic University ethics committee. All participants gave consent before participating in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants gave consent before participating in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- González-Pernía, J.L.; Peña-Legazkue, I.; Vendrell-Herrero, F. Innovation, entrepreneurial activity and competitiveness at a sub-national level. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 45, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Kirst, A.L.; Bergmann, H.; Bird, B. Entrepreneurs’ actions and venture success: A structured literature review and suggestions for future research. Small Bus. Econ. 2023, 60, 199–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, T. The impact of entrepreneurship on economic, social and environmental welfare and its determinants: A systematic review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2021, 71, 553–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieger, P.; Raemy, L.; Zellweger, T.; Fueglistaller, U.; Braun, I. Global Student Entrepreneurship 2021: Insights from 58 Countries; KMU-HSG/IMU: St. Gallen, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dodgson, M.; Gann, D. Why Universities Should Support More Student Entrepreneurs. Here’s Why—And How. World Economic Forum. 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/10/universities-should-support-more-student-entrepreneurs/ (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Walter, S.G.; Block, J.H. Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, A.; Ali, S.; Shakil, M.H.; Mukarram, M.; Haider, S.Z. Cultivating Entrepreneurial Minds: Unleashing Potential in Pakistan’s Emerging Entrepreneurs Using Structural Equational Modeling. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Guo, X.; Chinnasamy, J. Advancing entrepreneurship education in Pakistan: A review of the literature. In Entrepreneurship Education and Internationalisation: Cases, Collaborations and Contexts; Crammond, R.J., Hyams-Ssekasi, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, G.; Le, T.T.T.; Tran, A.K.T.; Du, T. Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Vietnam: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning orientation. Educ. Train. 2021, 63, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A.; Urbano, D.; Dandolini, G.A.; de Souza, J.A.; Guerrero, M. Innovation and entrepreneurship in the academic setting: A systematic literature review. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Mundorf, N.; Salzarulo-McGuigan, A. Entrepreneurship education enhances entrepreneurial creativity: The mediating role of entrepreneurial inspiration. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. The cognitive perspective: A valuable tool for answering entrepreneurship’s basic “why” questions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A.; Krueger, N.; Walmsley, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, S.; Aliakbari, A.; Alizadeh Majd, A.; Bell, R. The effect of entrepreneurship education on graduate students’ entrepreneurial alertness and the mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset. Educ. + Train. 2022, 64, 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Shi, J.; Zhang, J. From entrepreneurship education to entrepreneurial intention: Mindset, motivation, and prior exposure. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 954118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garavan, T.N.; O′Cinneide, B. Entrepreneurship Education and Training Programmes: A Review and Evaluation–Part 2. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1994, 18, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperopoulos, P.; Dimov, D. Burst bubbles or build steam? Entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intentions. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 970–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Lančarič, D.; Egerová, D.; Czeglédi, C. The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsaris, C.; Vamvaka, V. Attitude toward entrepreneurship: Structure, prediction from behavioral beliefs, and relation to entrepreneurial intention. J. Knowl. Econ. 2016, 7, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E.J.; Shepherd, D.A.; Venugopal, V. A multi-motivational general model of entrepreneurial intention. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 106107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; An, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, P. The role of entrepreneurship policy in college students’ entrepreneurial intention: The intermediary role of entrepreneurial practice and entrepreneurial spirit. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 585698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Sharifi-Tehrani, M.; Pratt, S.; Altinay, L. Understanding entrepreneurial intentions: A developed integrated structural model approach. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzner, I.M. Competition and Entrepreneurship; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Kacmar, K.M.M.; Busenitz, L. Entrepreneurial alertness in the pursuit of new opportunities. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 27, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavoushi, Z.H.; Zali, M.R.; Valliere, D.; Faghih, N.; Hejazi, R.; Mobini Dehkordi, A. Entrepreneurial alertness: A systematic literature review. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2020, 33, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzner, I.M. Entrepreneurial discovery and the competitive market process: An Austrian approach. J. Econ. Lit. 1997, 35, 60–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lanivich, S.E.; Levasseur, L.; Pidduck, R.J.; Busenitz, L.W.; Tang, J. Advancing entrepreneurial alertness: Review, synthesis, and future research directions. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucbasaran, D.; Westhead, P.; Wright, M. The extent and nature of opportunity identification by experienced entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valliere, D. Towards a schematic theory of entrepreneurial alertness. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, C.M.; Katz, J.A. The psychological basis of opportunity identification: Entrepreneurial alertness. Small Bus. Econ. 2001, 16, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.S.; Shepherd, D.A. Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.G.; MacMillan, I.C. The Entrepreneurial Mindset: Strategies for Continuously Creating Opportunity in an Age of Uncertainty; Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Williams, T.A.; Patzelt, H. Thinking about entrepreneurial decision making: Review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 998–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.S.; Kier, A.S. Triggers and enablers of social innovation: Entrepreneurial mindsets in action. Soc. Enterp. J. 2016, 12, 378–401. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y. Entrepreneurial mindset: A systematic review and future research agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 2–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.; Bansal, S. Viewing marketing through entrepreneurial mindset: A systematic review. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2021, 16, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daspit, J.J.; Fox, C.J.; Findley, S.K. Entrepreneurial mindset: An integrated definition, a review of current insights, and directions for future research. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 12–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. A verbal measure of information rate for studies in environmental psychology. Environ. Behav. 1974, 6, 233. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen, Q.; Nadeem, M.S.; Raziq, M.M.; Sajjad, A. Linking individuals’ resources with (perceived) sustainable employability: Perspectives from conservation of resources and social information processing theory. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2022, 24, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwu, C.G.; Opute, P.A.; Nchu, R.; Eresia-Eke, C.; Tengeh, R.K.; Jaiyeoba, O.; Aliyu, O.A. Entrepreneurship education, curriculum and lecturer-competency as antecedents of student entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Noboa, E. Social entrepreneurship: How intentions to create a social venture are formed. In Social Entrepreneurship; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2006; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Vega, R.; Kaartemo, V.; Lages, C.R.; Razavi, N.B.; Männistö, J. Reshaping the contexts of online customer engagement behavior via artificial intelligence: A conceptual framework. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Wong, H.Y.; Azam, M.S. How perceived communication source and food value stimulate purchase intention of organic food: An examination of the stimulus-organism-response (SOR) model. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirhadi, M.; Zali, M.R.; Faghih, N.; Hejazi, R. The effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial alertness: The mediating role of entrepreneurial skills and character. J. Entrep. Educ. 2021, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. Entrepreneurial alertness: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchiarini, M.; Muldoon, J.; Smith, D.; Boling, R.J. Experiential learning in an online setting: How entrepreneurship education changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Entrep. Educ. Pedagog. 2024, 7, 190–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe-White, T.; McGee, E. Toward a race-conscious entrepreneurship education. Entrep. Educ. Pedagog. 2024, 7, 161–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outsios, G.; Kittler, M. The mindset of UK environmental entrepreneurs: A habitus perspective. Int. Small Bus. J. 2018, 36, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, S.; Wardana, L.W.; Wibowo, A.; Narmaditya, B.S. Does entrepreneurship education and culture promote students’ entrepreneurial intention? The mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset. Cogent Educ. 2021, 8, 1918849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilenga, N.; Dhliwayo, S.; Chebo, A.K. The entrepreneurial mindset and self-employment intention of high school learners: The moderating role of family business ownership. In Frontiers in Education; Frontiers Media SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 7, p. 946389. [Google Scholar]

- Aima, M.H.; Wijaya, S.A.; Carawangsa, L.; Ying, M. Effect of global mindset and entrepreneurial motivation to entrepreneurial self-efficacy and implication to entrepreneurial intention. Dinasti Int. J. Digit. Bus. Manag. 2020, 1, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaffka, G.; Krueger, N. The entrepreneurial ‘mindset’: Entrepreneurial intentions from the entrepreneurial event to neuroentrepreneurship. In Foundational Research in Entrepreneurship Studies: Insightful Contributions and Future Pathways; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, L. Entrepreneurial passion to entrepreneurial behavior: Role of entrepreneurial alertness and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelderen, M.; Brand, M.; van Praag, M.; Bodewes, W.; Poutsma, E.; van Gils, A. Explaining entrepreneurial intentions by means of the theory of planned behaviour. Career Dev. Int. 2006, 11, 538–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, C.F.; Karami, M.; Tang, J.; Roldan, L.B.; Santos, J.A. Entrepreneurial alertness: A meta-analysis and empirical review. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2023, 19, e00394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami, A.S. Catalysts of Prosperity: How Networking Support and Training Programmes Drive Growth Aspirations in Saudi Arabia’s Micro and Small Enterprises. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linan, F.; Chen, Y. Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables measurement error. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; p. 197. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Psychological approaches to entrepreneurial success a general model an overview of findings. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Cooper, C.L., Robertson, I.T., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2000; pp. 101–142. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).