Evaluation of Public Space in Beijing’s Old Residential Communities from a Female-Friendly Perspective

Abstract

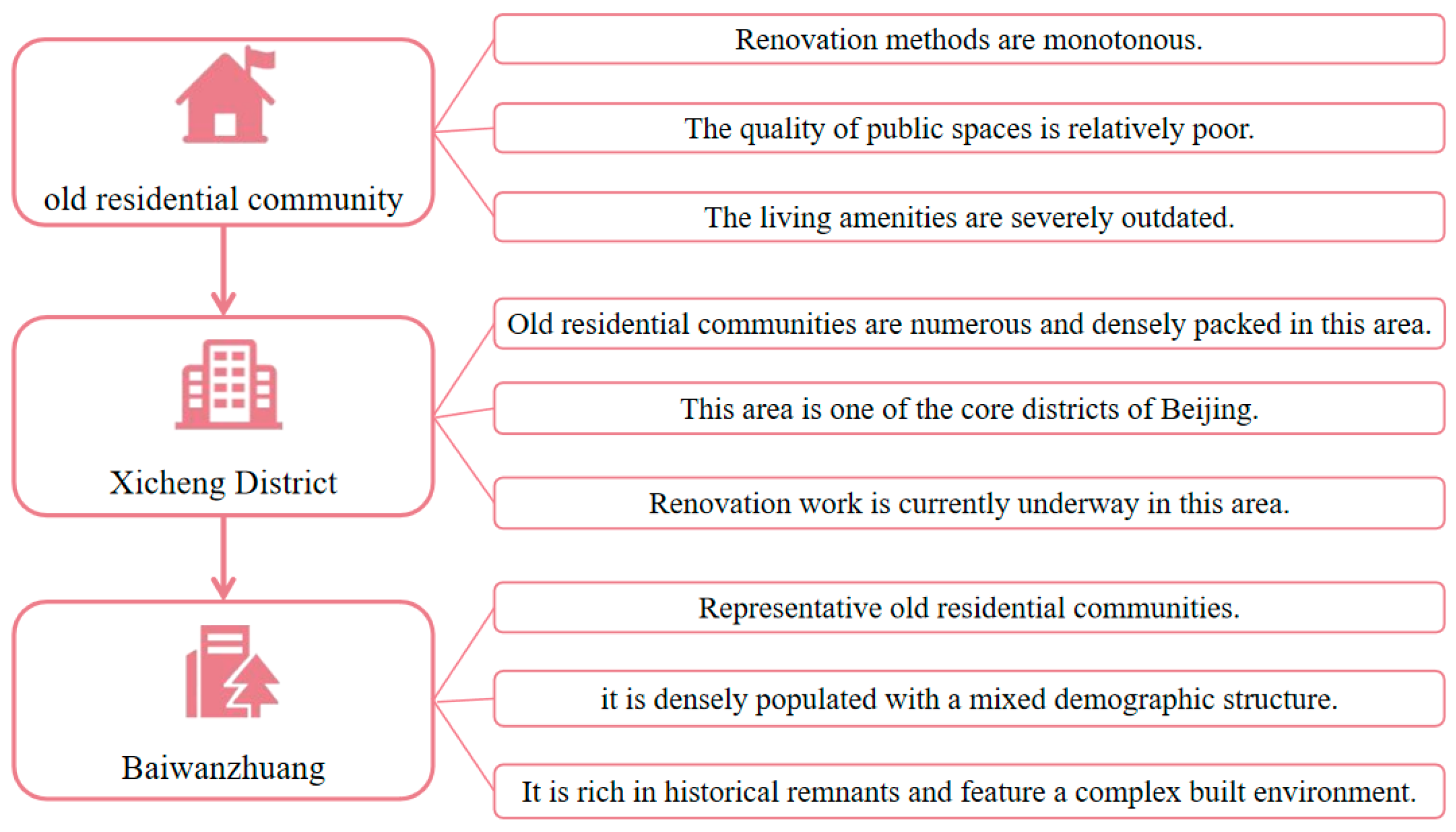

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Female Characteristics

2.2. Women-Friendly Public Spaces

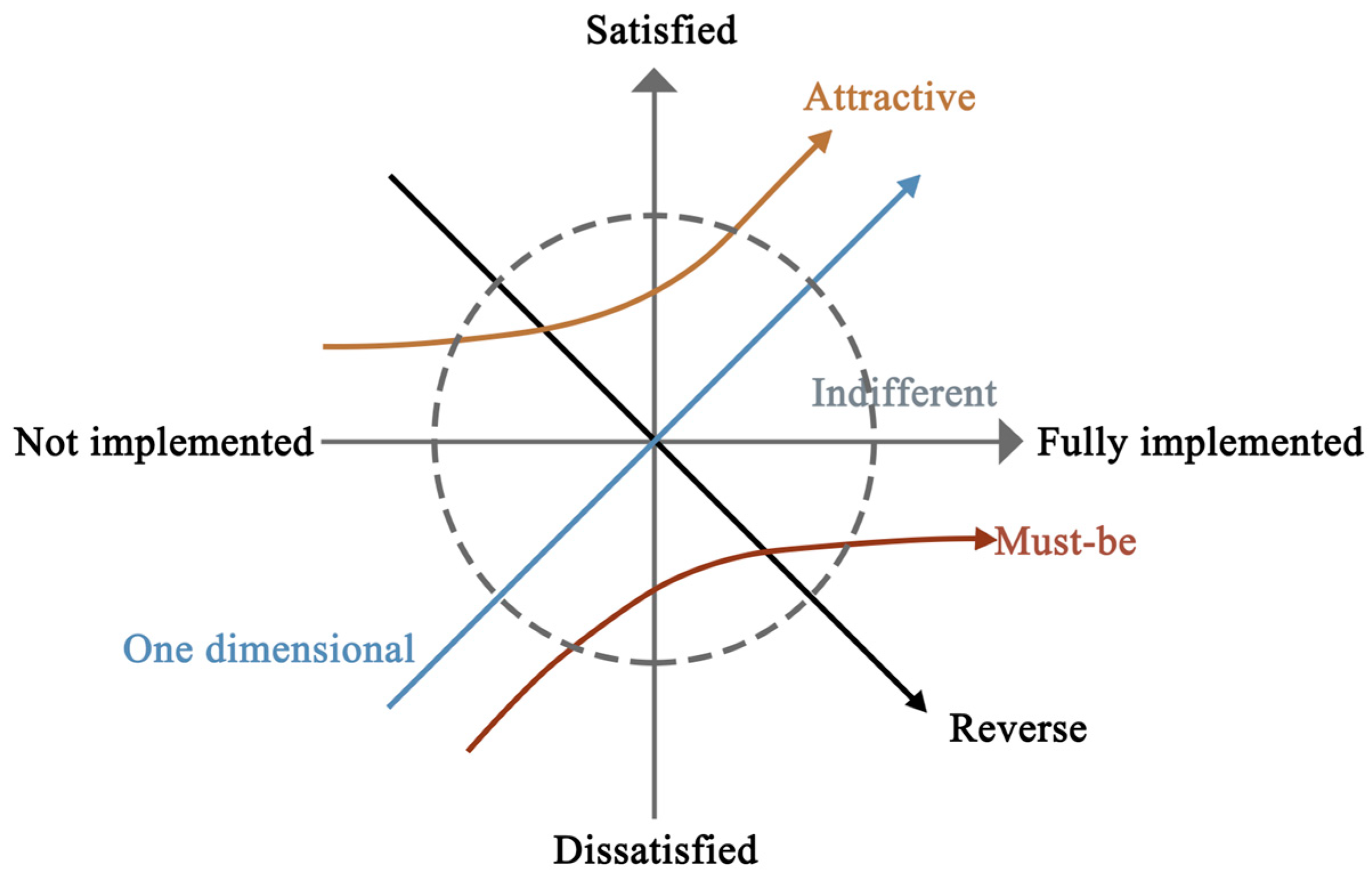

2.3. The KANO Model

- (1)

- Better = (O + A)/(M + O + A + I)

- (2)

- Worse = (−1) × (O + M)/(M + O + A + I)

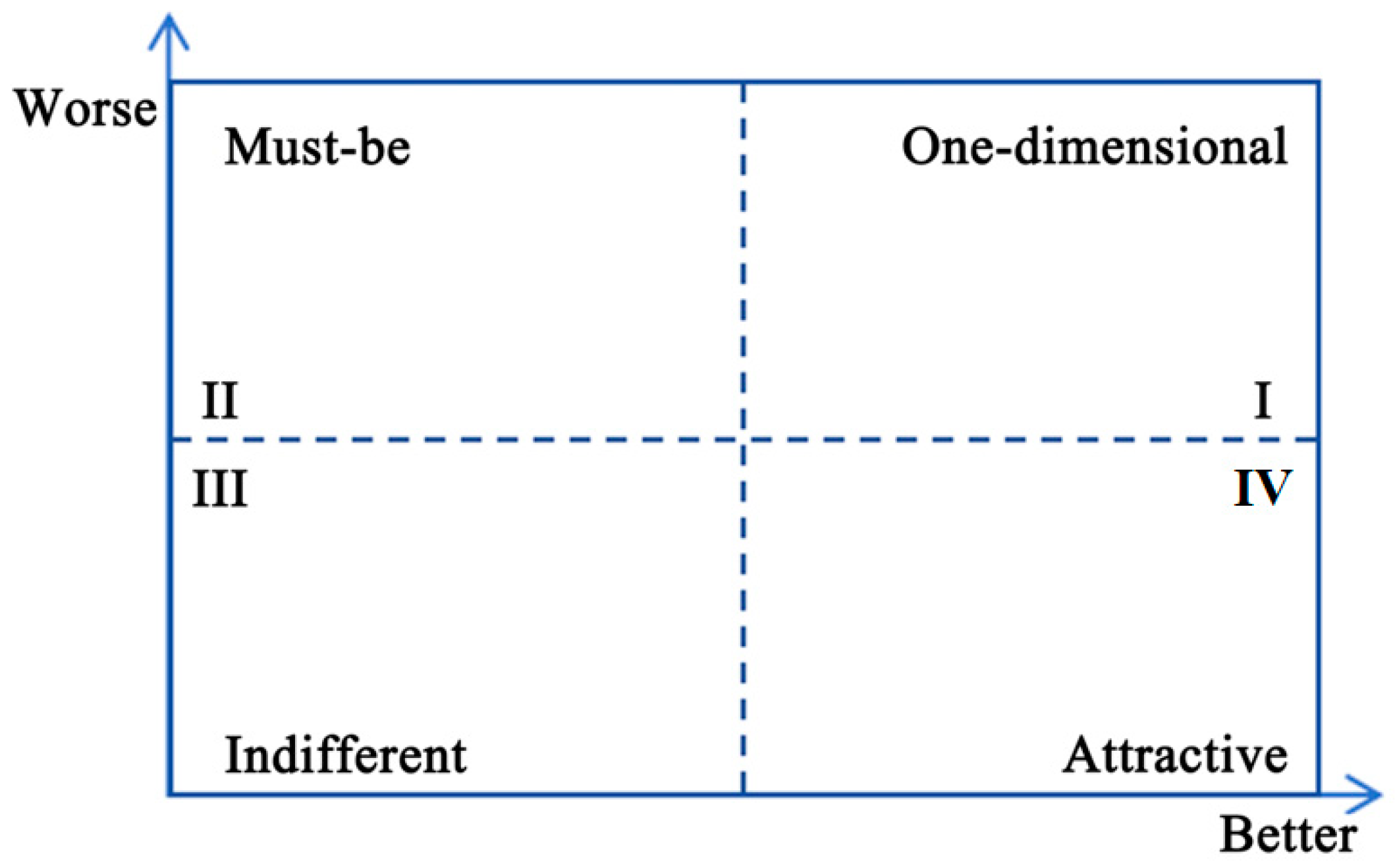

2.4. IPA

3. Evaluation and Results

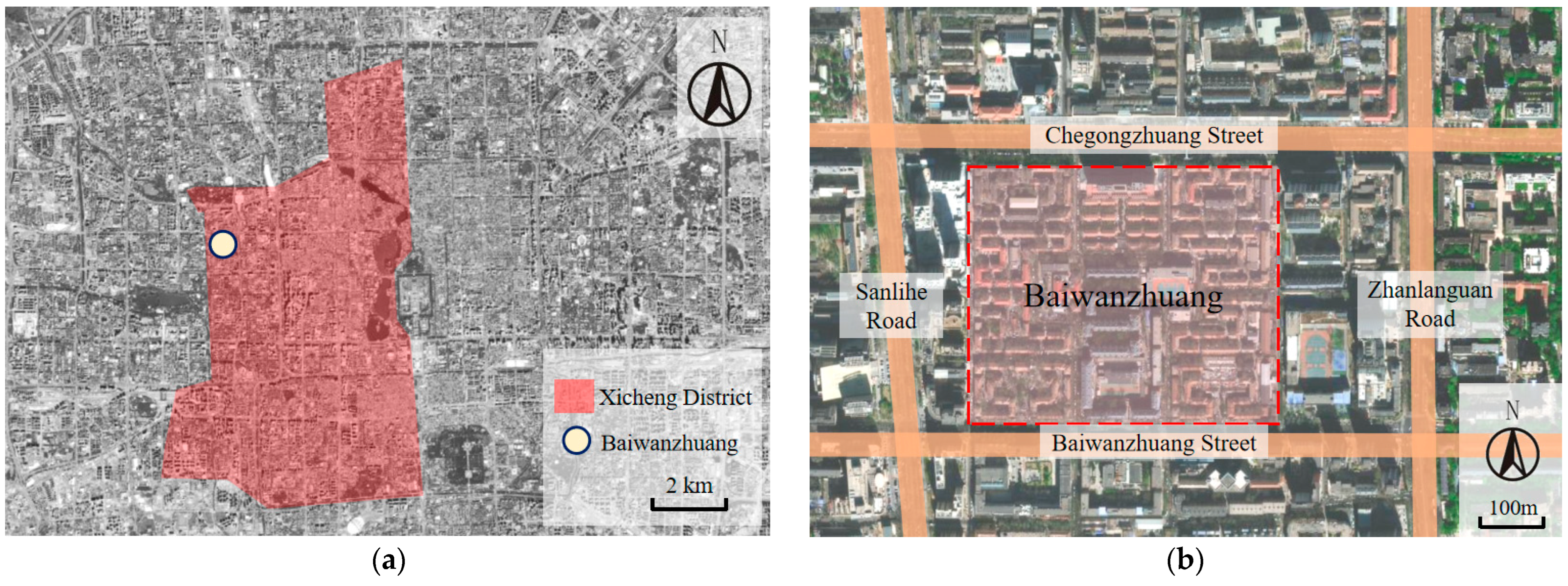

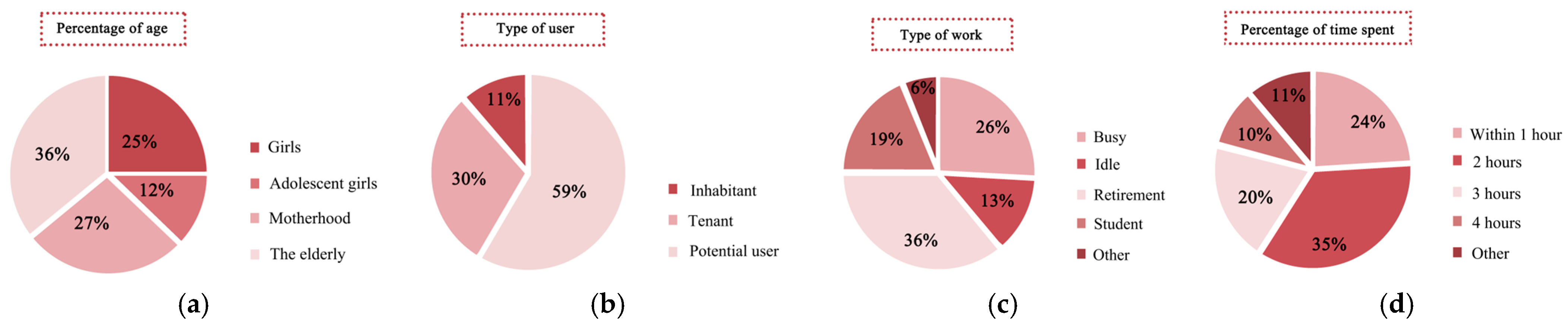

3.1. Research Areas and Targets

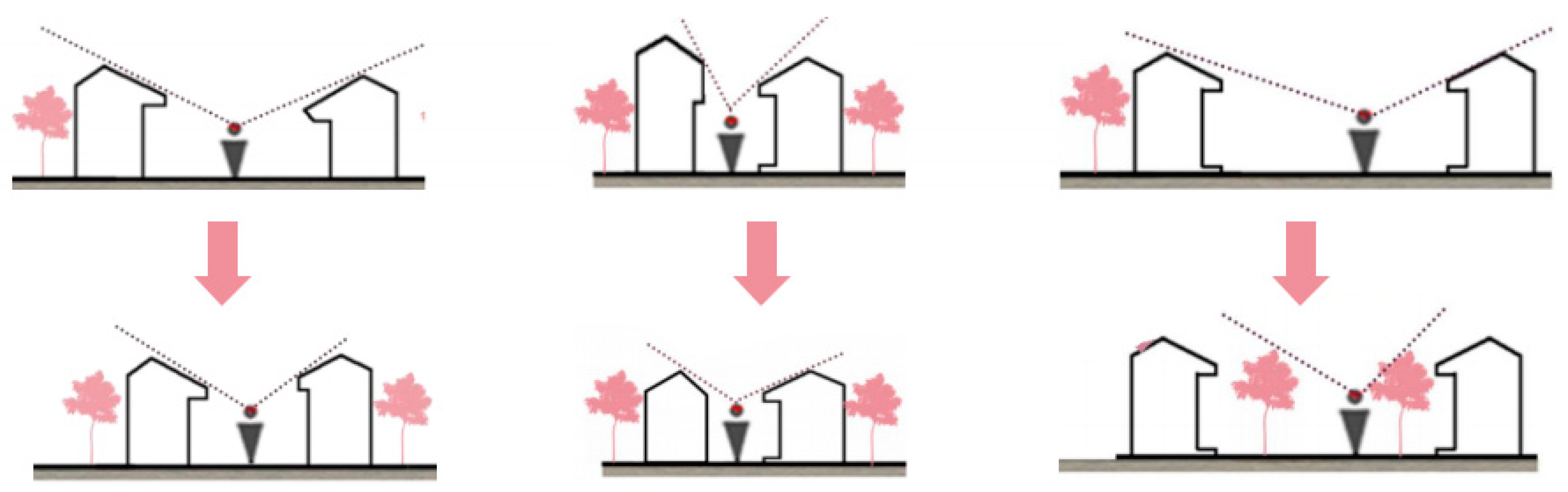

3.1.1. Classification of Public Spaces in Old Residential Communities

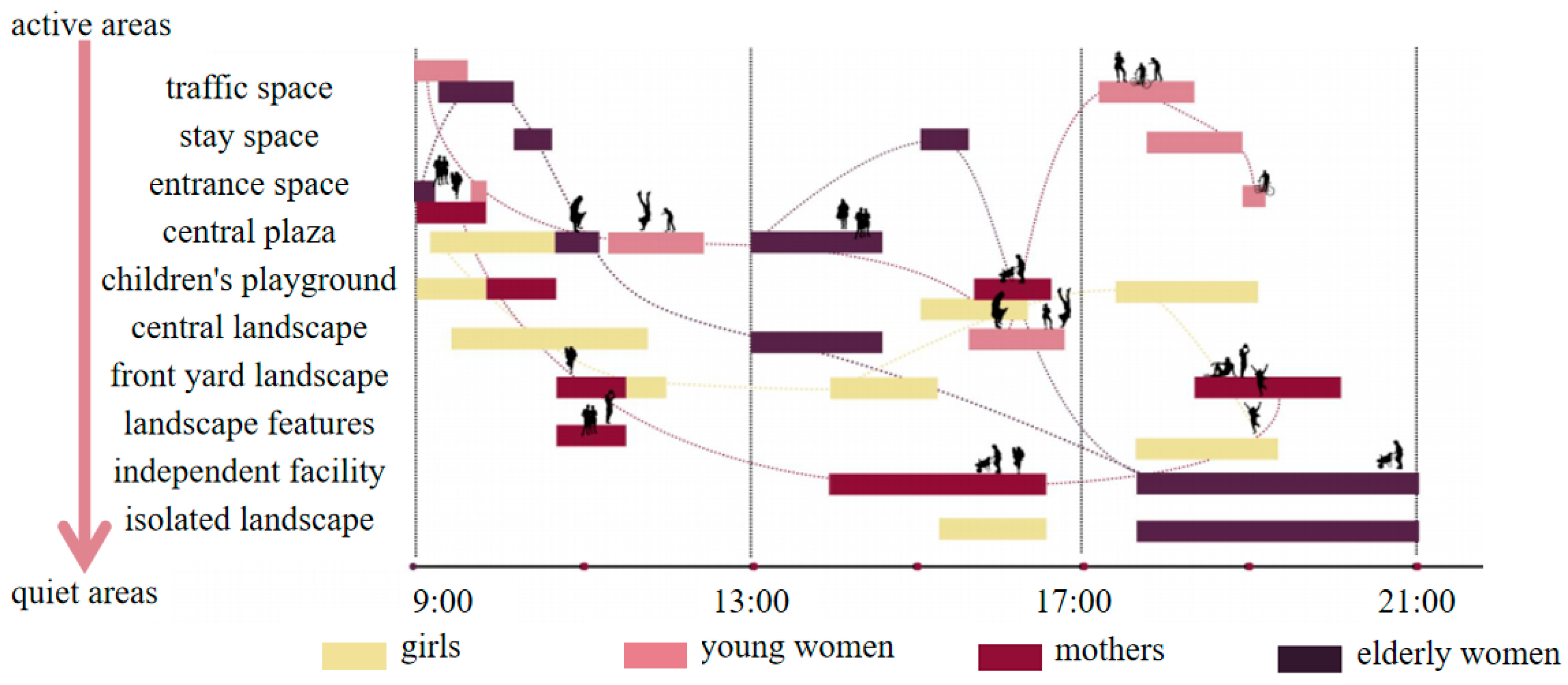

3.1.2. Analysis of Female User Behavior

3.2. Evaluation Index System

3.3. Evaluation of Public Spaces in Old Residential Communities

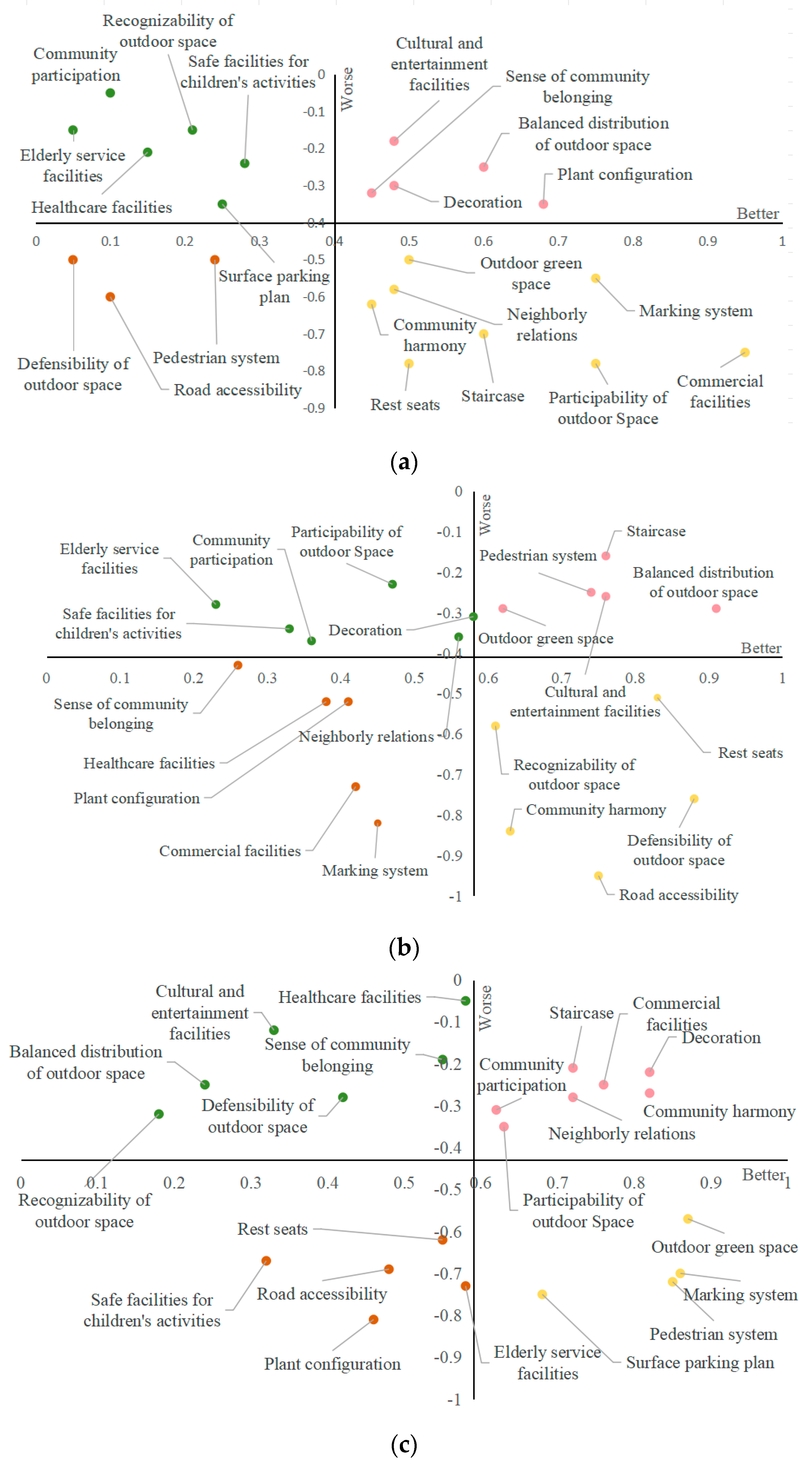

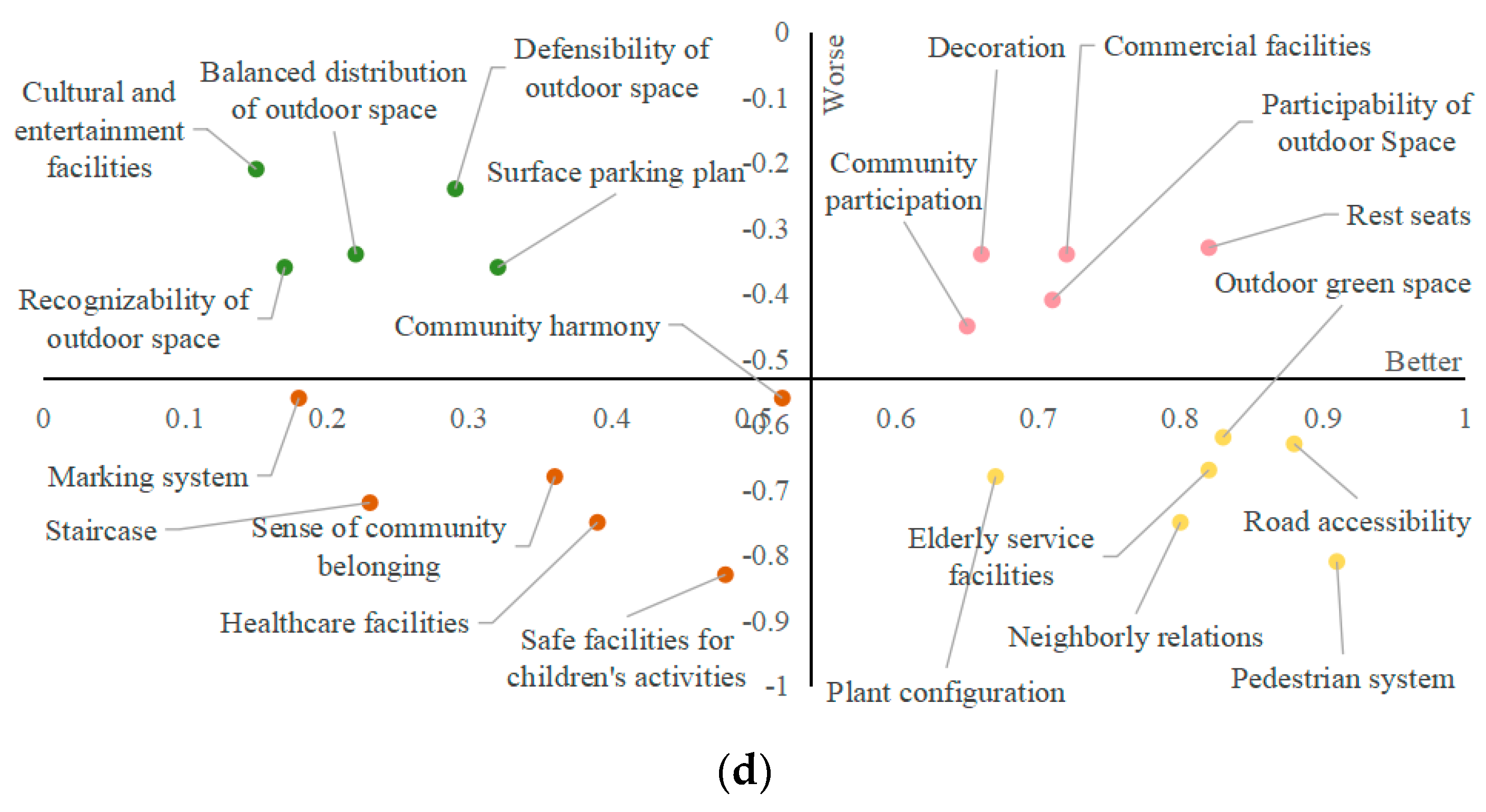

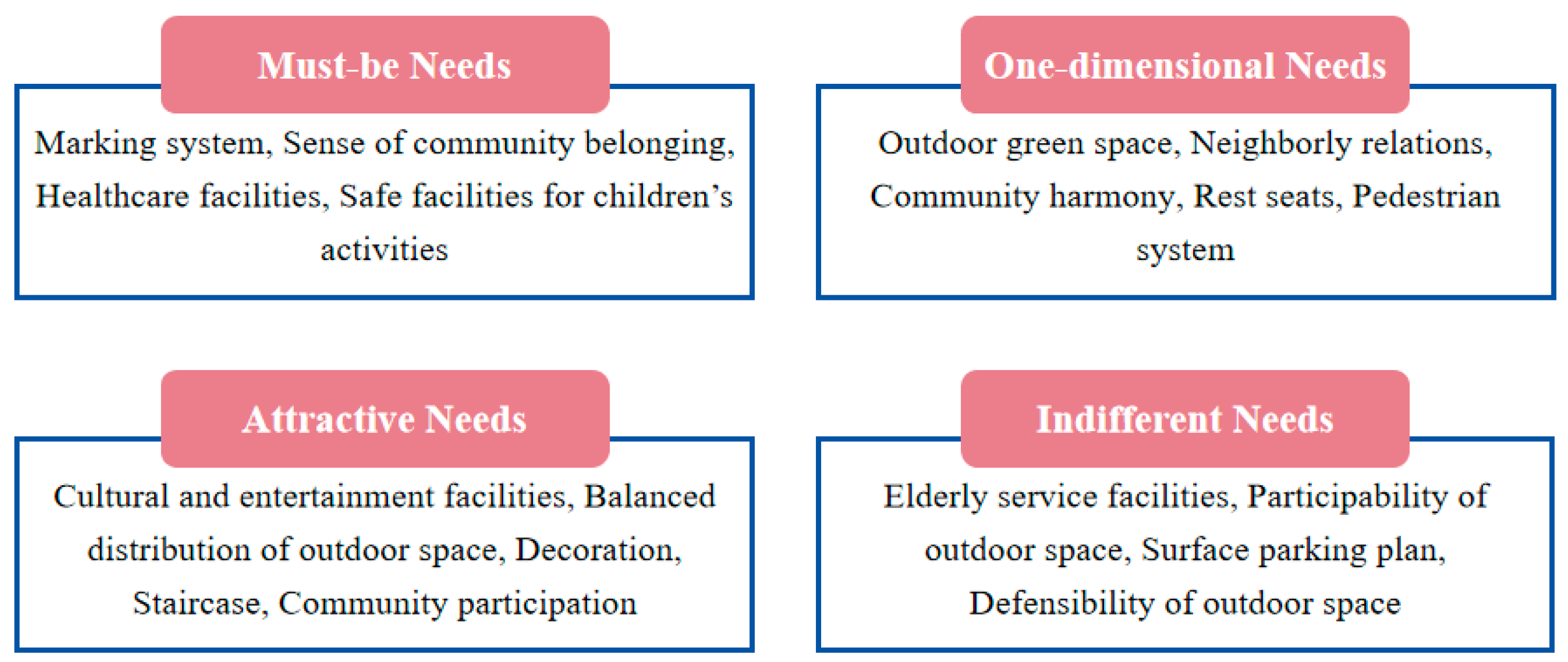

3.3.1. The KANO Model

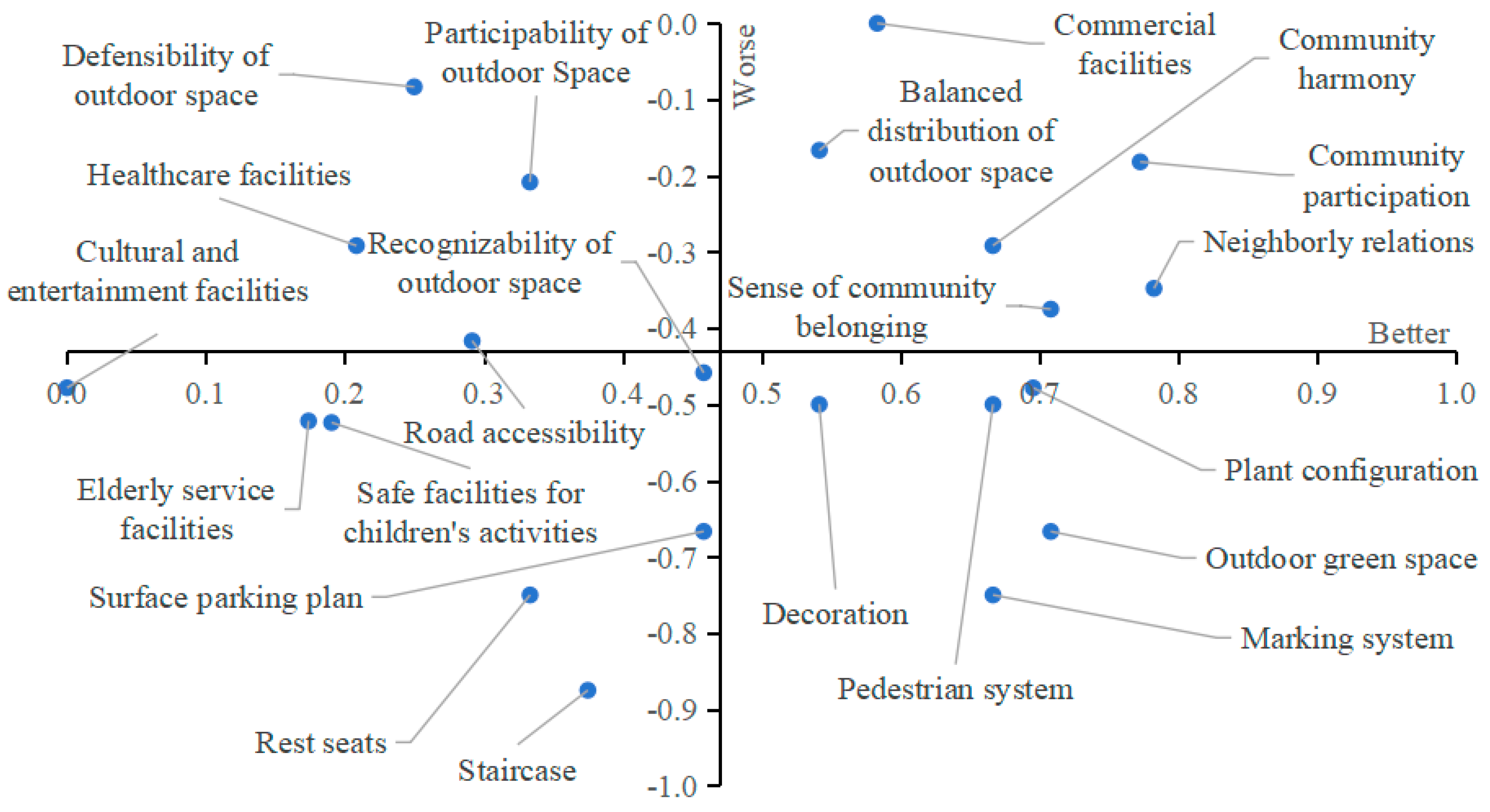

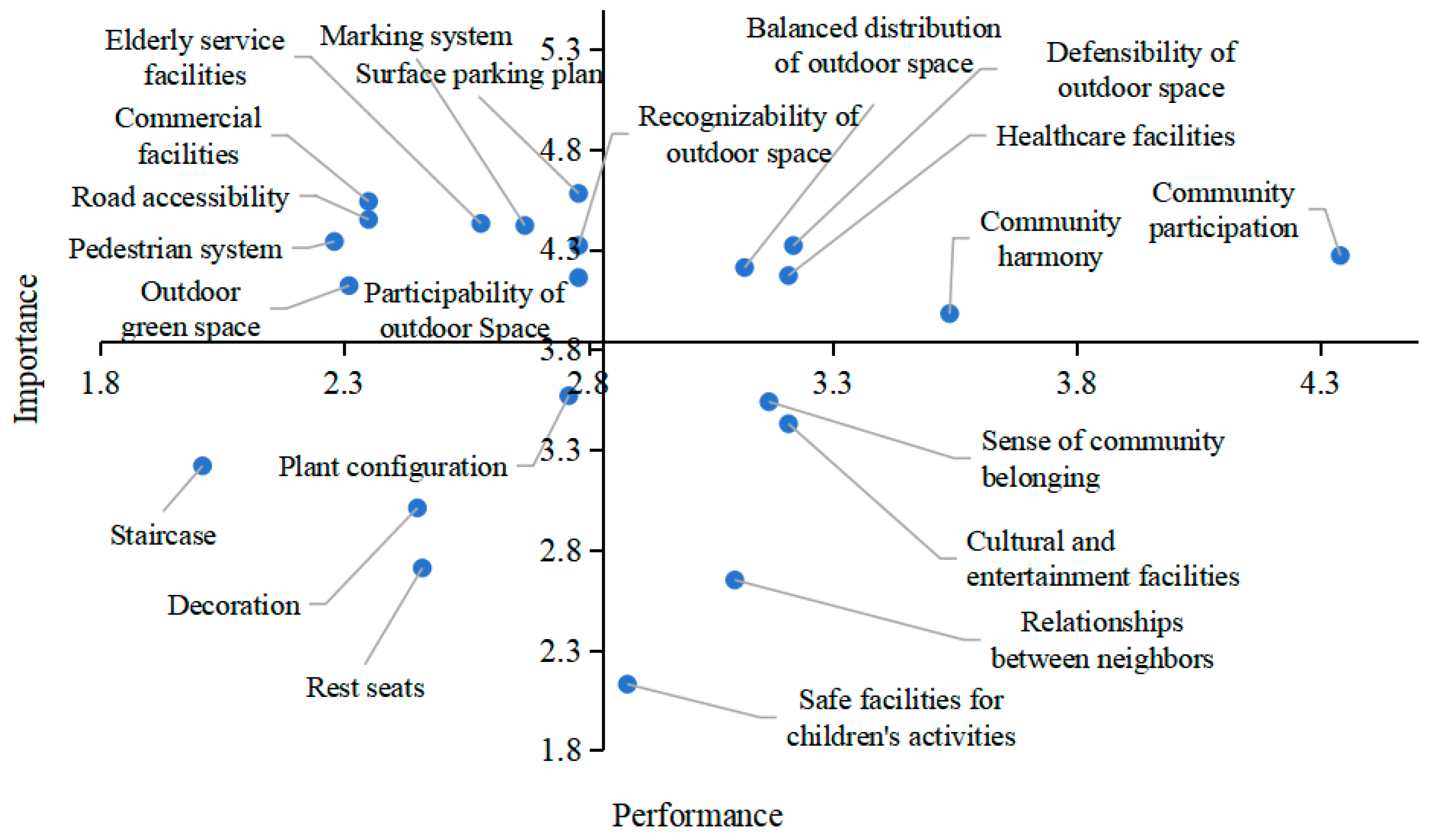

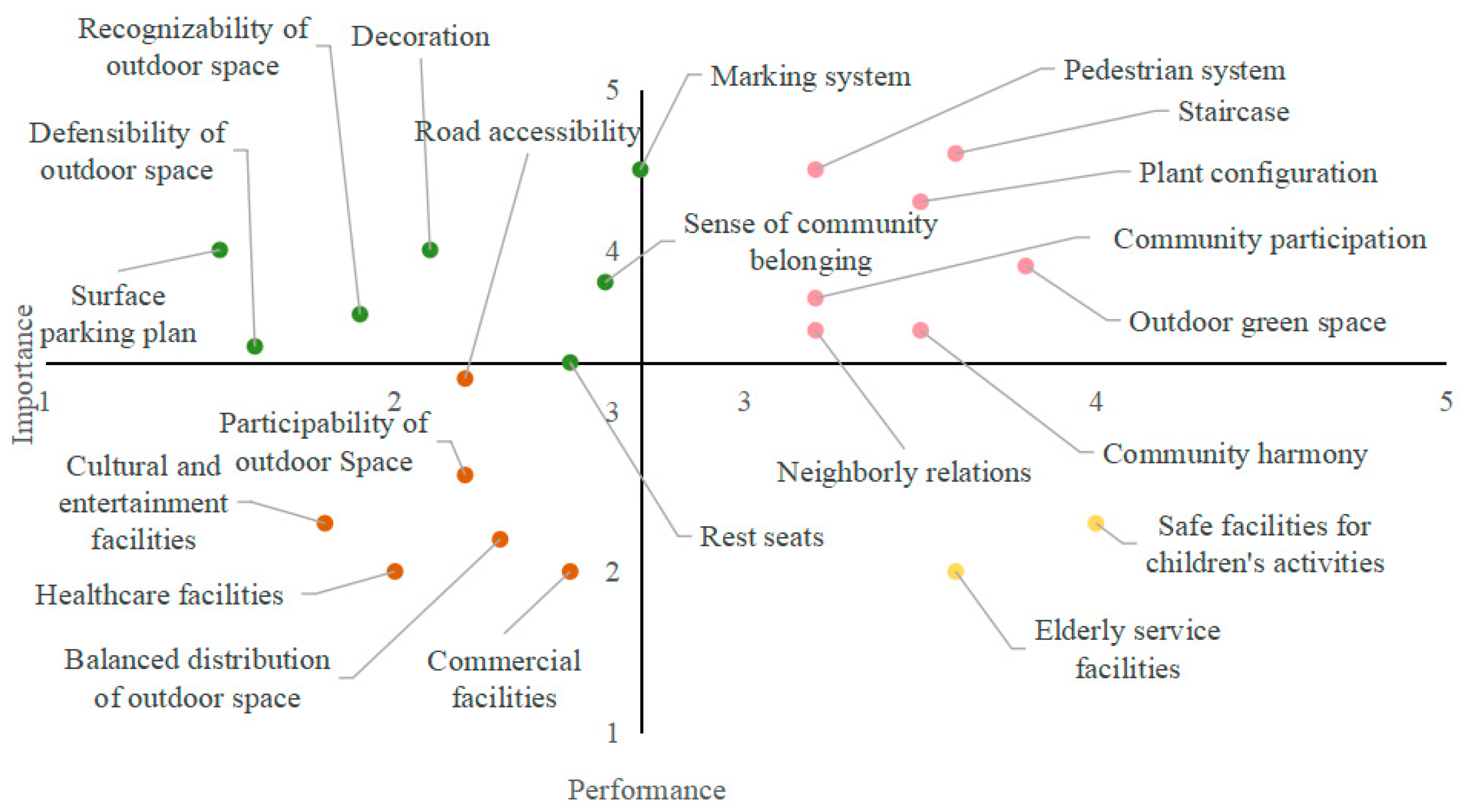

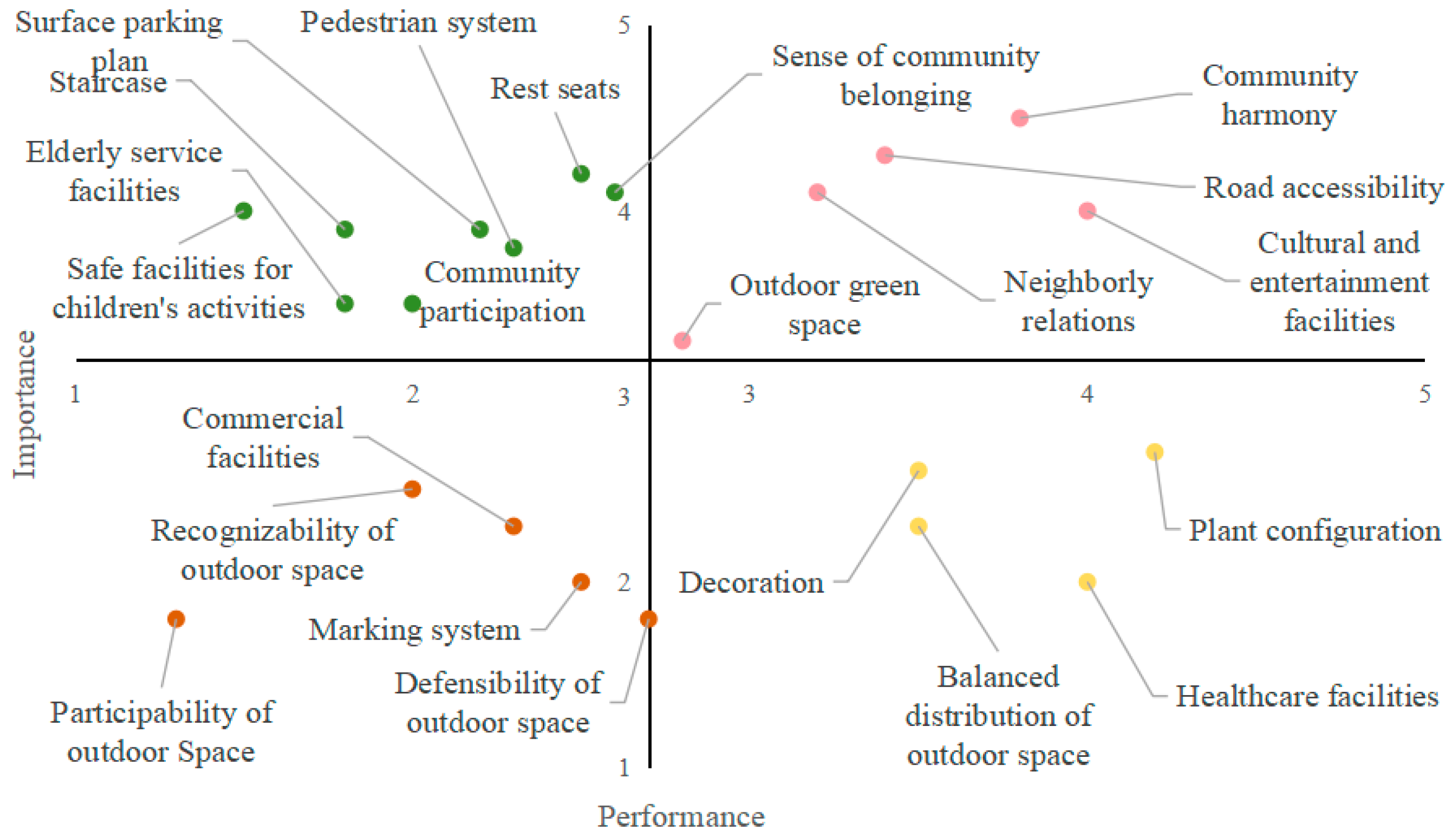

3.3.2. IPA

4. Discussion

4.1. Female Users’ Requirement Type Analysis

4.2. IPA

4.3. Summary of Female Users’ Requirements

- (1)

- Traffic Safety: Safety is at the core of living spaces designed for women. It is essential to address the psychological and physical safety concerns of female users, providing them with a secure and reliable living environment.

- (2)

- Public Facilities: Well-developed public facilities form the foundation of spaces for female activities. Meeting the specific needs of women at different age stages by providing appropriate spaces and services is crucial for enhancing their sense of belonging.

- (3)

- Habitable Outdoor Activities: A livable outdoor activity space reflects a healthy lifestyle for women. Providing a highly accessible and easily recognizable environment is an important criterion for assessing the suitability of a community for its residents.

- (4)

- Harmonious Cultural Environment: A harmonious cultural environment is a source of women’s sense of belonging. A community with good neighborly relations can achieve a high level of recognition from female residents.

4.4. Optimization Strategies for Public Spaces in Old Residential Communities from a Female-Friendly Perspective

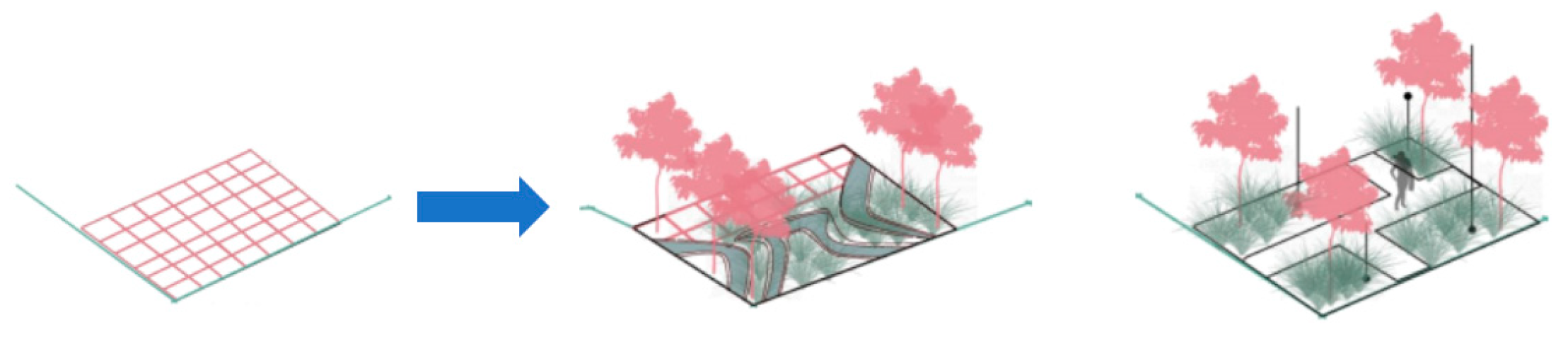

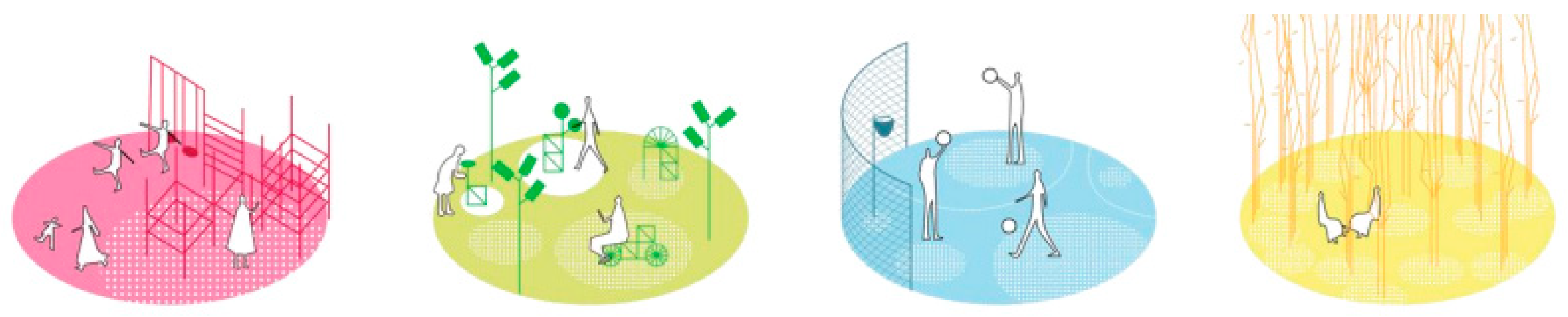

4.4.1. Increase Space Types to Meet Diverse Needs

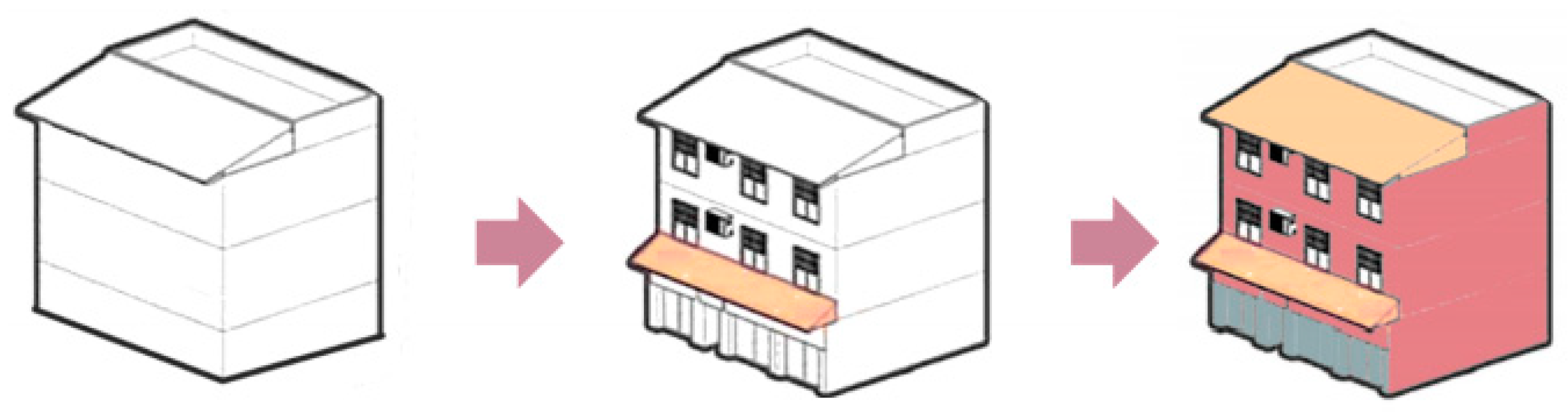

4.4.2. Enhance Spatial Facilities and Refine Space Management

4.4.3. Enhance Environmental Atmosphere and Improve Spatial Aesthetics

4.4.4. Clear Policy Direction and Enhanced Social Care

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levy, C. Travel choice reframed: “deep distribution” and gender in urban transport. Environ. Urban. 2013, 25, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kodmany, K. Women’s visual privacy in traditional and modern neighborhoods in Damascus. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2000, 17, 283–303. [Google Scholar]

- Women Friendly Cities. Available online: http://www.kadindostukentler.com/project.php (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- UN-Habitat. Women’s Equal Rights to Housing, Land and Property in International Law. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/womens-equal-rights-to-housing-land-and-property-in-international-law (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- UN-Habitat. Gender Equality for Smarter Cities: Challenges and Progress. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/gender-equality-for-smarter-cities-challenges-and-progress (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Making Cities Safer for Women: UN Report Calls for Radical Rethink|UN News. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/10/1129752 (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Shenzhen Government Online. The First “Gender Equality Demonstration Point” in Shenzhen. Available online: https://www.sz.gov.cn/cn/xxgk/zfxxgj/zwdt/content/post_9475855.html (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- National Working Committee on Children and Women under State Council. Women Friendly for a Better City. Available online: https://www.nwccw.gov.cn/2024/03/14/99519861.html (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Zheng, S.W.; Yang, S.J.; Ma, M.H.; Dong, J.; Han, B.L.; Wang, J.Q. Linking cultural ecosystem service and urban ecological-space planning for a sustainable city: Case study of the core areas of Beijing under the context of urban relieving and renewal. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, D.; Jiang, Y. The impacts of relationships between critical barriers on sustainable old residential neighborhood renewal in China. Habitat Int. 2020, 103, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Deng, X.Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, Z.H.; Wang, L.S. Assessment of the impact of climate change on cities livability in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 726, 138339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.Y. Unveiling citizen-government interactions in urban renewal in China: Spontaneous online opinions, reginal characteristics, and government responsiveness. Cities 2024, 148, 104857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.Q. Research on the Index System of Old Neighborhood Renovation Based on Green Building Evaluation Standard. J. Archit. Res. Dev. 2024, 8, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Wu, Y.; Jiao, L. Community Governance in Age-Friendly Community Regeneration—A Case Study on Installing Elevators in Old Residential Buildings. Buildings 2024, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Miao, X.F.; Geng, W.Y.; Li, Z.W.; Li, L. Comprehensive renovation and optimization design of balconies in old residential buildings in Beijing: A study. Energy Build. 2023, 295, 113296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.S.; Yun, W.; Wei, M.F. A survey on the satisfaction of living environment in old urban residential areas from the perspective of public infrastructure. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Proceedings of the International Conference on Architecture, Civil and Hydraulic Engineering (ACHE2019), Guangzhou, China, 20–22 December 2019; IOP Publishing: Beijing, China, 2020; Volume 794, p. 012071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zhang, P. Research on the Application of a New Type of Trash Can in the Renovation of Old Communities. J. Sociol. Ethnol. 2022, 4, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. Research on Energy Saving Measures of Residential District Lighting System. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Proceedings of the International Conference on Architecture, Civil and Hydraulic Engineering (ACHE2018), Dalian, China, 20–22 July 2018; IOP Publishing: Beijing, China, 2019; Volume 569, p. 022018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, G.; Man, X.X.; Wang, Q.Q. Discussion on the characteristics and renovation technologies of the heating system in Chinese urban residential areas from perspectives of heat sources. Energy Build. 2024, 307, 113966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.Y.; Wang, J.; Han, X.; Wei, W.Z.; Guo, Y.H.; Liu, J. Natural ventilation of underground shelters to improve indoor thermal and moisture environments in the various climates of China. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. Inc. Trenchless Technol. Res. 2024, 153, 105916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.J.; Du, B.W.; Lv, L.P.; Gao, J.; Zhang, C.Q.; Tong, L.Q.; Liu, G.D. Occupant exposure and ventilation conditions in Chinese residential kitchens: Site survey and measurement for an old residential community in Shanghai. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 31, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.Y.; Maruthaveeran, S.; Shahidan, M.F.; Chu, Y.C. Landscape Preference Evaluation of Old Residential Neighbourhoods: A Case Study in Shi Jiazhuang, Hebei Province, China. Forests 2023, 14, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.S.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, G.W. Study on Spatial Optimization Strategies of Old Community Streets Based on Spatial Syntax and PSPL-A Case Study of Garden Hill Community in Grain Road Street, Wuhan City. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Computer Technology and Media Convergence Design (CTMCD 2022), Dali, China, 13–15 May 2022; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2022; pp. 724–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.W.; Liu, Y.; Cui, C.Y.; Xia, B. Influence of Outdoor Living Environment on Elders’ Quality of Life in Old Residential Communities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Wang, Y.Q.; Shen, Z.C.; Wang, Y.T. Research on the Correlations between Spatial Morphological Indices and Carbon Emission during the Operational Stage of Built Environments for Old Communities in Cold Regions. Buildings 2023, 13, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, X.; Feng, Z. Age-friendly cities and communities and cognitive health among Chinese older adults: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Studies. Cities 2023, 132, 104072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.L.; van den Berg, P.; Arentze, T. A new measurement method of parental perception of child friendliness in neighborhoods to improve neighborhood quality and children’s health and well-being. Cities 2024, 149, 104955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C. Research on Urban Community Public Space Design Based on Children’s Psychological Needs—A Case Study and Survey of Chengdu Yulin East Road. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 7, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, F.T.; Wang, S.X.; Wang, Z.Q.; Wang, Y.C.; Qin, G.; Wang, P.; Liu, M.; Huang, L. Lighting characteristics of public space in urban functional areas based on SDGSAT-1 glimmer imagery: A case study in Beijing, China. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 306, 114137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H. Research on Urban Public Space Planning and Design Based on Women’s Perspective. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2007. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.C. Research on the difference of urban public space based on feminist perspective—Taking the commercial pedestrian street of Shilu in Suzhou City as an example. J. Suzhou Inst. Sci. Technol. (Eng. Technol. Ed.) 2016, 29, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.X.; Zheng, Y.Q. Safety of Women and Public Space Design. Urban Archit. 2020, 17, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.Y. Research on Residential Space Design for Urban Single Women from a Female Perspective; Jilin University of Architecture: Jilin, China, 2023. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, X.; Wang, Y. Evaluation of the Intergenerational Equity of Public Open Space in Old Communities: A Case Study of Caoyang New Village in Shanghai. Land 2023, 12, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.Y.; Cheng, W.; Ma, C.P.; Tan, Y.Y.; Xin, L.S. On public space design for Chinese urban residential area based on integrated architectural physics environment evaluation. In Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Energy Materials and Environment Engineering, Bangkok, Thailand, 10–12 March 2017; IOP Publishing: Beijing, China, 2017; Volume 61, p. 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabak, M.; Norouzi, N.; Abdullah, A.M.; Khan, T.H. Evaluating common spaces in residential communities: An examination of the relationship between perceived environmental quality of place and residents’ satisfaction. Life Sci. J. 2014, 11, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Ma, H.; Wang, M.H.; Li, J.Q. Construction and improvement strategies of an age-friendly evaluation system for public spaces in affordable housing communities: A case study of Shenzhen. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1399852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Fang, D. Exploring Public Space Satisfaction in Old Residential Areas Based on Impact-Asymmetry Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.D.; Tang, X.M. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Community Public Open Space Renewal: A Case Study of the Ruijin Community, Shanghai. Land 2022, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wu, D.J. Research on Commercial Complex Architectural Design from a Female Perspective. Archit. Cult. 2024, 7, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. Optimization Strategies for Public Spaces in Subway Stations Based on a Female Perspective: A Case Study of Chengdu. Urban Archit. 2021, 18, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Kong, F.; Luo, Y.M.; Zeng, S.Y.; Lan, J.J.; You, X.Q. Gender differences in large-scale and small-scale spatial ability: A systematic review based on behavioral and neuroimaging research. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Duan, W.; Dong, S. Research on Leased Space of Urban Villages in Large Cities Based on Fuzzy Kano Model Evaluation and Building Performance Simulation: A Case Study of Laojuntang Village, Chaoyang District, Beijing. Buildings 2024, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Luh, D.; Hu, L.; Shan, Q. Exploring Factors Affecting Residential Satisfaction in Old Neighborhoods and Sustainable Design Strategies Based on Post-Occupancy Evaluation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y. Research on the Evaluation of Tourist Satisfaction in Wuhan City Tourism Destinations Based on the Quadrant Graph Model. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Water Resource and Environment, Tokyo, Japan, 23–26 August 2020; IOP Publishing: Beijing, China, 2020; Volume 612, p. 012070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.F.; Liu, H. Development of Neighborhood Residences in China: A Case Study of Baiwanzhuang. J. Landsc. Res. 2019, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.T.; Wu, K.J. Quantitative evaluation of the potential of underground space resources in urban central areas based on multiple factors: A case study of xicheng district, Beijing. Procedia Eng. 2016, 165, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pan, J.; Qian, Y. Collaborative governance for participatory regeneration practices in old residential communities within the Chinese context: Cases from Beijing. Land 2023, 12, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Function/Service | Negative Questions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Like (5 Points) | Must Be (4 Points) | Neutral (3 Points) | Live with (2 Points) | Dislike (1 Point) | ||

| Positive Questions | Like (5 points) | Q | A | A | A | O |

| Must be (4 points) | R | I | I | I | M | |

| Neutral (3 points) | R | I | I | I | M | |

| Live with (2 points) | R | I | I | I | M | |

| Dislike (1 point) | R | R | R | R | Q | |

| Category | Clarification | Example | Icon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public passage spaces | Traffic space and stay space |  |  |

| Recreational interaction spaces | Community entrance space, central plaza, and children’s playground |  |  |

| Landscape viewing spaces | Central landscape, front yard landscape, and landscape features |  |  |

| Private resting spaces | Independent facility space and isolated landscape space. |  |  |

| Sample Type | Interviewee Profile | Feedback on the Content of the Interviews |

|---|---|---|

| girl | A 12-year-old girl, in the fifth grade of elementary school; lives with her grandparents. | She enjoys participating in activities with other girls and prefers quiet activities, usually within the courtyard. Boys generally congregate at the community center, each having their own “territories”. |

| Young women | A 21-year-old woman, a university student, who has lived in the community for a long time. | She usually engages in activities as part of her family unit. Due to the lack of diverse, aesthetically pleasing, and engaging facilities, she does not often participate in activities within the community. |

| mother | A 35-year-old mother with an 8-year-old child; a community worker. | She needs to constantly watch over her child and is concerned about the child being injured. The child’s daily activities constitute her entire activity. There is a lack of facilities, and taking the child out requires carrying a lot of things. |

| elderly women | A 71-year-old retired woman, who has lived in the community for a long time. | She has a reduced social circle and engages in relatively monotonous activities. Her activity routes are highly similar to those of other elderly people, leading to a somewhat monotonous lifestyle. |

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Traffic Safety | Road accessibility | Good road accessibility within the community, with no intersections. |

| Pedestrian system | Roads within the community are well-paved, non-slip, brightly colored, and paved with materials convenient for stroller use. | |

| Staircase | Parking within the community is orderly, and parking planning does not occupy spaces for women’s activities. | |

| Surface parking plan | Equipped with non-slip measures, adequate lighting, and stairwells that are user-friendly for women. | |

| Marking system | The community has traffic signs and night lighting systems that are easy for women to recognize. | |

| Public Facilities | Commercial facilities | The community has a variety of evenly distributed commercial service facilities. |

| Healthcare facilities | The community has a community health service station or nearby hospital/clinic. | |

| Safe facilities for children’s activities | Children’s activity spaces are fenced and have planted tree walls to facilitate childcare by women. | |

| Elderly service facilities | The community has elderly service facilities such as a senior community service center or elderly care homes. | |

| Cultural and entertainment facilities | The community has cultural and recreational facilities that meet the needs of various groups. | |

| Rest seats | Public spaces are equipped with seating for rest, with a reasonable and even layout. | |

| Outdoor Activity Comfort | Balanced distribution of outdoor space | Activity spaces are evenly and reasonably distributed. |

| Participability of outdoor Space | Public spaces are appropriately scaled and capable of hosting various activities, with high female participation. | |

| Defensibility of outdoor space | Peripheral areas have good security systems, with a defensible space design and unobstructed sightlines in public spaces. | |

| Recognizability of outdoor space | Public space routes mainly use simple linear or open circular designs with continuity elements, clear directions, prominent main entrances, and few forks. | |

| Decoration | Building facades and landscape features (sculptures, water features) are aesthetically pleasing, and the materials and color-coordination of public space surfaces are comfortable. | |

| Outdoor green space | High greenery rate in public spaces, with a rich seasonal variety of plants. | |

| Plant configuration | Plant arrangement is reasonable, with no thorny, poisonous plants, or plants with exposed roots. | |

| Cultural Environment Harmony | Relationships between neighbors | Public spaces are rich in layers, with smooth transitions and effective connections between independent spaces, facilitating female social interactions and harmonious neighborhood relations. |

| Sense of community belonging | Women are generally satisfied with the functionality, aesthetics, and accessibility of community public spaces. | |

| Community participation | Public spaces have diverse functions and activity types, with high levels of female participation in community activities. | |

| Community harmony | Public spaces are suitable for use by various groups, including women, with a high degree of harmony. |

| Function/Service | A | O | M | I | R | Q | Results | Better | Worse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Road accessibility | 25.00% | 4.17% | 37.50% | 33.33% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Must-have | 29.17% | −41.67% |

| Pedestrian system | 25.00% | 41.67% | 8.33% | 25.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | One-dimensional | 66.67% | −50.00% |

| Staircase | 0.00% | 37.50% | 50.00% | 12.50% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Must-have | 37.50% | −87.50% |

| Surface parking plan | 16.67% | 29.17% | 37.50% | 16.67% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Must-have | 45.84% | −66.66% |

| Marking system | 0.00% | 66.67% | 8.33% | 25.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | One-dimensional | 66.67% | −75.00% |

| Commercial facilities | 58.33% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 41.67% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Attractive | 58.33% | 0.00% |

| Healthcare facilities | 4.16% | 16.67% | 12.50% | 66.67% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Indifferent | 20.84% | −29.17% |

| Safe facilities for children’s activities | 12.50% | 4.17% | 41.67% | 29.17% | 12.50% | 0.00% | Must-have | 19.05% | −52.38% |

| Elderly service facilities | 16.67% | 0.00% | 50.00% | 29.17% | 0.00% | 4.17% | Must-have | 17.39% | −52.17% |

| Cultural and entertainment facilities | 0.00% | 0.00% | 45.83% | 50.00% | 4.17% | 0.00% | Indifferent | 0.00% | −47.82% |

| Rest seats | 4.17% | 29.17% | 45.83% | 20.83% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Must-have | 33.34% | −75.00% |

| Balanced distribution of outdoor space | 45.83% | 8.33% | 8.33% | 37.50% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Attractive | 54.17% | −16.66% |

| Participation in outdoor space | 20.83% | 12.50% | 8.33% | 58.33% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Indifferent | 33.33% | −20.83% |

| Defensibility of outdoor space | 20.83% | 4.17% | 4.17% | 70.83% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Indifferent | 25.00% | −8.34% |

| Recognizability of outdoor space | 16.67% | 29.17% | 16.67% | 37.50% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Indifferent | 45.84% | −45.84% |

| Decoration | 33.33% | 20.83% | 29.17% | 16.67% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Attractive | 54.16% | −50.00% |

| Outdoor green space | 20.83% | 50.00% | 16.67% | 12.50% | 0.00% | 0.00% | One-dimensional | 70.83% | −66.67% |

| Plant configuration | 25.00% | 41.67% | 4.17% | 25.00% | 0.00% | 4.17% | One-dimensional | 69.56% | −47.83% |

| Relationships between neighbors | 50.00% | 25.00% | 8.33% | 12.50% | 4.17% | 0.00% | Attractive | 78.26% | −34.78% |

| Sense of community belonging | 45.83% | 25.00% | 12.50% | 16.67% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Attractive | 70.83% | −37.50% |

| Community participation | 62.50% | 8.33% | 8.33% | 12.50% | 8.33% | 0.00% | Attractive | 77.27% | −18.18% |

| Community harmony | 41.67% | 25.00% | 4.17% | 29.17% | 0.00% | 0.00% | Attractive | 66.66% | −29.17% |

| Service Quality Element | Classification | Performance | Importance | I/P | Improvement Order | Keep Order |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Road accessibility | Concentrate area | 2.35 | 4.45 | 1.89 | 3 | |

| Pedestrian system | Concentrate area | 2.28 | 4.34 | 1.90 | 2 | |

| Staircase | Low priority | 2.01 | 3.22 | 1.60 | 10 | |

| Above-ground parking plan | Concentrate area | 2.78 | 4.58 | 1.65 | 7 | |

| Marking system | Concentrate area | 2.67 | 4.42 | 1.66 | 6 | |

| Commercial facilities | Concentrate area | 2.35 | 4.54 | 1.93 | 1 | |

| Healthcare facilities | Keep up the good work | 3.21 | 4.17 | 1.30 | 3 | |

| Safe facilities for children’s activities | Additional resource | 2.88 | 2.13 | 0.74 | 9 | |

| Elderly service facilities | Concentrate area | 2.58 | 4.43 | 1.72 | 5 | |

| Cultural and entertainment facilities | Additional resource | 3.21 | 3.43 | 1.07 | 7 | |

| Rest seats | Low priority | 2.46 | 2.71 | 1.10 | 13 | |

| Attached public seating | Keep up the good work | 3.12 | 4.21 | 1.35 | 1 | |

| Participation in outdoor space | Concentrate area | 2.78 | 4.16 | 1.50 | 9 | |

| Defensibility of outdoor space | Keep up the good work | 3.22 | 4.32 | 1.34 | 2 | |

| Recognizability of outdoor space | Concentrate area | 2.78 | 4.32 | 1.55 | 8 | |

| Decoration | Low priority | 2.45 | 3.01 | 1.23 | 12 | |

| Outdoor green space | Concentrate area | 2.31 | 4.12 | 1.78 | 4 | |

| Plant configuration | Low priority | 2.76 | 3.57 | 1.29 | 11 | |

| Neighborly relations | Additional resource | 3.10 | 2.65 | 0.85 | 8 | |

| Sense of community belonging | Additional resource | 3.17 | 3.54 | 1.12 | 6 | |

| Community involvement | Keep up the good work | 4.34 | 4.27 | 0.98 | 5 | |

| Community harmony | Keep up the good work | 3.54 | 3.98 | 1.12 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Q.; Hou, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of Public Space in Beijing’s Old Residential Communities from a Female-Friendly Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198387

Li Q, Hou D, Zhang Z, Chen Z, Li W, Liu Y. Evaluation of Public Space in Beijing’s Old Residential Communities from a Female-Friendly Perspective. Sustainability. 2024; 16(19):8387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198387

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Qin, Dongchen Hou, Ziwei Zhang, Zonghao Chen, Wenlong Li, and Yijun Liu. 2024. "Evaluation of Public Space in Beijing’s Old Residential Communities from a Female-Friendly Perspective" Sustainability 16, no. 19: 8387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198387

APA StyleLi, Q., Hou, D., Zhang, Z., Chen, Z., Li, W., & Liu, Y. (2024). Evaluation of Public Space in Beijing’s Old Residential Communities from a Female-Friendly Perspective. Sustainability, 16(19), 8387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198387