Abstract

Literature on African urbanism has generally lacked insight into the significant roles of hunters and fishers as city founders. This has resulted in a knowledge gap regarding the cultural foundation of the cities that could enhance policy frameworks for sustainable urban governance. This article examines corollaries related to the complementarities of hunting and urbanism with case studies from the ethno-linguistic Yoruba region in southwestern Nigeria. Through qualitative methodologies involving ethnography and the (oral) history of landscapes of hunting from the pre-colonial and (British) colonial periods, as well as tracing the current cultural significance of hunting in selected Yoruba cities, the article reveals data that identify hunters and fishers as city founders. It shows that hunting, as a lived heritage, continues to be interlaced with cultural urban practices and Yoruba cosmology and that within this cultural imagery and belief, hunters remain key actors in nature conservation, contributing to socio-cultural capital, economic sustainability, and urban security structures. The article concludes with recommendations for strategies to reconnect with these value systems in rapidly westernizing urban Africa. These reconnections include the re-sacralization of desacralized landscapes of hunting, revival of cultural ideologies, decolonization from occidental conceptions, and re-definition of urbanism and place-making in light of African perspectives despite globalization. In doing so, the article contributes to a deeper understanding of the interconnections between the environmental and societal components of sustainability theory, agenda, and practice in urban contexts; underscores the societal value of lived heritage, cultural heritage, and cultural capital within the growing literature on urban social sustainability; and sheds more light on southern geographies within the social sustainability discourse, a field of study that still disproportionately reflects the global northwest.

1. Setting the Stage: Introductory Note

Africa’s projected urban growth is striking, with an urbanization rate of 1.1 percent per year, second only to Asia’s 1.24 percent [1]. West Africa is considered its second most rapidly urbanizing sub-region and one of the world’s least developed regions, facing challenges that constitute the primary targets of the global sustainability agenda. With its growing population of over 170 million, Nigeria is a West African country that includes megacities such as Lagos—one of the largest urban agglomerations in Africa, alongside Cairo and Kinshasa [2]. The future of such bustling and challenging southern urban centers calls for profound re-imagination and global repositioning in the world of cities and for a positive approach increasingly supported by leading urbanists and international development agencies. Amid the constant erosion of urban greenspaces and cultural landscape values due to accelerated demographics, urban congestion, and competition, the study strives to highlight and reframe the ecological and cultural assets of lived heritage in Nigeria’s southwestern region. It seeks to identify the potential of the region’s local urban communities through three exemplary loci—Osogbo, Ibadan, and Lagos—to utilize these eco-cultural assets to foster social sustainability through place-making and place-keeping strategies. By re-evaluating the lived experiences and memories of these urban communities and tying together environmental and societal aspects to substantial urban challenges and global changes, the study also aligns with Goal 11 of the UN SDG 2030 agenda: “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable”; it especially resonates with the sole paragraph in the SDG agenda that mentions “heritage” and thus connects the past with the present in planning for the urban future, Target 11.4, which aims to “strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage” [3] (p. 26).

Place-making is a “set of social, political and material processes by which people iteratively create and recreate the experienced geographies in which they live” [4] constituted by socio-spatial interactions that tie individuals together through a common place-related frame. Analyzing place-making strategies in the geography in question of Nigeria’s southwestern region is crucial; as urbanist John Friedmann notes, “since the 1990s, interest in place (as opposed to space) has surged across a spectrum of social science disciplines including planning. But the empirical focus has been chiefly on cities along the Atlantic Rim even as vast new areas in Asia, Africa, and Latin America were undergoing accelerated urbanization” [5] (p. 149). The aim of the article is to analyze the historical and present-day spatialities of hunting and fishing in southwestern Nigeria as fragile eco-cultural constructs of place-based urban communities. Embracing a people-centered, culture-grounded planning approach demonstrates that sustaining eco-cultural place-making assets is a collaborative task involving many stakeholders, both official and unofficial. The article is based on historical and contemporary awareness of the region’s urbanities and interviews of key informants with an emphasis on hunting and fishing environments. These insights also offer actionable recommendations for long-term management, or the “place-keeping” [6,7], of urban green and open spaces in southwestern Nigeria against the background of the subcontinent’s fragile urban management systems and constraining factors.

After this introductory section on the relevant historiographic tendencies and thematic intersections in the associated fields of research literature, the article proceeds in two main sections. Section 2 briefly illuminates the relationship between the city and human ecology as central to the urban phenomenon of past and present while commenting on the role of ancient myths that tie together hunting and city-making. It serves as a background for Section 3, which deals with the lived heritage and spatialities of hunters as founders of three urban loci in the Yoruba region of southwestern Nigeria. Section 3 subsequently frames the lived heritage of the relevant communities in the context of urban ecology and the ethos of settlement establishment. This implies that the globalization, modernization, and westernization of southern regions through (post-)imperial and (post-)colonial hegemonies cannot erase the primeval reality of the ingenuity of hunters and fishermen as city founders.

In this section, the examination of the three urban loci of Osogbo, Ibadan, and Lagos is based on a case-study methodology, effective for understanding contemporary real-life phenomena in a specific site-related context by employing multiple sources of evidence [8]. We believe that our exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory approach to these loci, which combines versatile data from secondary sources and fieldwork, contributes towards a more multifaceted analysis of this eco-cultural phenomenon. In addition, the use of ethnographic methods, particularly in-depth interviews regarding this eco-cultural phenomenon that has existed since time immemorial, is especially important in the context of sub-Saharan Africa. This is due to the fact that pre-colonial traditional societies in the region were primarily oral societies whose languages were not written, and documenting their oral traditions is still a vividly ongoing project, crucial for historical, archaeological, and environmental reconstruction [9,10].

Based on interviews with key informants, this Section 3, “Yoruba Cityscape Symbolisms of Hunting and Fishing”, reveals information about the communities in question, the role of open and green spaces in their everyday life, ritual occasions, cultural beliefs, and social ethos. The interviews were conducted face-to-face at each respective site on different occasions between 2023 and mid-2024, with the interviewee’s consent obtained upon informing them of the research aims, questions, and methods. The key informants were selected for their representative roles in their respective communities, particular socio-cultural awareness, and ecological sensitivity, whether as civil servants (as the Chief Education Officer in the first case study of Oṣun Grove, Oṣogbo), traditional priests (as the Aboke of Ibadan Hills in the second case study), or local scientists and elderly elite (as the marine ecologist and former royal-lineage descendant in Lagos, the third case study). We have interwoven the most relevant parts of their original words into the discussion without interference. These excerpts were chosen because of their important implications for understanding the interconnectedness between physical landscapes and narrative landscapes in the contemporary West African city, linking pasts, presents, and futures of place-making and place-keeping practices.

We believe that this interconnectedness is a strength of the article, demonstrating the intimate relationship between the tangible and intangible through memory, imagination, and symbolic perception. By bringing together actual landscapes and people’s explanations of their landscapes—historical facts and stories—narrative landscapes radiate back onto the physical place, making it natural and real [11,12]. As Feng et al. posit, “The study of cultural heritage with a landscape narrative is a way to find the past, from individual perception and cognition, which can help individuals and groups to induce a deep understanding of the cultural heritage value” [13] (p. 5). Supported by material-heritage findings and associated bottom-up oral histories and accumulated community memories—this section reveals more off-the-radar urban experiences through this qualitative ethnographic method of documenting oral traditions, read through an environmental lens. This environmental reading of Yoruba oral traditions in an urban context leads us to the Section 4, which offers feasible recommendations for designing an ecological, ethical, and social sustainability agenda inspired by Southern experiences. It aims, in this way, to create a more dialectic, multidirectional, and multiscale process of socially sustainable urban policy-making.

Within the mundane urban bustles and maintenance strategies of the space users, our ideas of the “city” in our everyday lives often lack considerations that call for a re-imagination of its foundation. Even as we embrace urban realities and modes of living within the city and its environment, we tend to use natural and other resources without any awareness or appreciation of the founders of the settlement and their backgrounds. Similarly, our cerebral hippocampus in the temporal lobe seldom considers the founders of other infrastructural networks such as terrestrial and air transportation, information and communication systems and associated gadgets, electronics, household wares, and fabrics, to name a few. As for the past, present, and future of urban agglomerations, reflections on their establishment and origins give us an opportunity to critically engage with urban social sustainability issues, with an emphasis on cultural capital. In addition to Pierre Bourdieu’s definition of cultural capital as the knowledge, behaviors, and skills acquired over time through socialization and education that have become institutionalized [14], we shall focus on the usability of this capital for urban policy design and for crystallizing the cultural heritage agenda at the city level, based on the valorization of place-making histories and community-making. Central questions in our discussion are the following: What is the city, and what role does nature play in it? Who are city founders, and what are their roles in the urban timespan as prominent urban actors? What place should we accord these founders in our everyday urban experiences as a means of commemorating them and appreciating their exploits? Additionally, how can the answers to these questions shape a more sustainable policy in Nigerian cities (and beyond) with an affinity to society and culture?

The discourse on cultural landscape as a scholarly concept has been evolving for about a century, originating from the field of cultural geography in Western academia. Carl Sauer’s pioneering 1925 position that “the cultural landscape is fashioned from a natural landscape by a cultural group. Culture is the agent, the natural area the medium, the cultural landscape is the result” [15] (p. 46) was soon embraced by sociologists, anthropologists, and scholars of architecture and urban studies. The basic understanding that cultural landscapes are geographic areas in which the interactions between human activity and the environment generate diverse ecological, social, cultural, economic, and political assemblages has opened rich and multidisciplinary research spectrums since the 1980s [16,17,18,19]. Recently, scholars deeply immersed in non-Western environmental conceptions and practices have highlighted the Western bias in some “international” cultural landscape definitions, such as that of UNESCO’s 1992 World Heritage Committee [20,21]. However, the integration of cultural landscape discourse into social sustainability theory is relatively recent, part of a growing trend in sustainability studies to investigate socio-cultural aspects as well, e.g., [22,23]. This trend has developed in sustainability studies since the 2000s [24], alongside the mainstream tendency to over-emphasize economic and environmental aspects.

Within social sustainability theory, traditional “hard” issues such as employment, health, poverty, and connectivity—although still dominant in the research agenda—are gradually giving way to “softer” issues. Increased attention is now given to cultural values and intangible subjects such as sense of place, place attachment, wellbeing, and livability, as well as to qualitative, semi-ethnographic methods, such as in-depth interviews [13,25]. Aligning with the sustainability agenda’s applicable essence and focus on the present and future, cultural heritage, place-making, and place-keeping definitions aim to inform participatory planning strategies. Thus, heritage studies [13,26], urban design, and landscape architecture literature [5,6,23] tend to promote cooperative division of responsibility among urban governments and social, cultural, and planning agencies (top-down, intermediate processes) and local communities (bottom-up processes). Under the sustainability agenda umbrella, these studies strive for the holistic multidirectional shaping (both top-down and bottom-up processes) of ecological and socio-cultural policies for good governance.

These research tendencies are significant for urban studies in general and for shaping southern perspectives and urban policies regarding open and green spaces in the city. Globally, statistics on urbanism show that currently, only 45% of the world’s population are not city dwellers, while 55% live in cities. Furthermore, the world’s urban population is projected to increase to about 70% by 2050; 90% of that increase is expected to occur in Asia and Africa [27]. In view of this demographic prediction, the American philosopher Jules Simon has called to “once again intentionally take up the task of philosophizing the city” and theorizing it, not only alongside urban studies scholars but also with “those intellectuals who have been influencing the very formation and normative functions of cities for more than two millennia, namely, philosophers” [27] (p. 387). We shall, therefore, trace back and “philosophize” on the role of hunters and fishers as city founders in their respective urban settlements and the formation of these settlements. Re-imagining and reframing these primeval moments in global urban history can contribute to an in-depth understanding of the essence of cities as human collective projects and to the fostering of the patrimonization of their social capital. However, in terms of historiography, this global process of building urban studies knowledge still tends to be Eurocentric (that is, Anglo-Americocentric) with regard to the generation of scholarly production and definitions of its theoretical mechanisms [28,29]. Thus, continuous exploration of southern urban contexts and experiences still constitutes a meaningful contribution to the accumulation of urban studies knowledge; hence, the signification of this article’s focus on hunters and fishers as city founders on an African sub-regional scale.

2. Between Nature of the City and Nature in the City

To borrow a “classical” definition of a city, American urban sociologists Robert Park (1864–1944) and Ernst Burgess (1886–1966) characterized the city as essentially societal and trans-physical in its essence, reflecting what they had interpreted as “human ecology”. According to them, the city is more than merely a physical mechanism; it is “a state of mind”, embodying a set of customs and traditions, attitudes, and sentiments. It is “involved in the vital processes of the people who compose it; it [the city] is a product of nature, and particularly of human nature” [30] (p. 1). In this definition, we sense the complimentary symbiosis between human and non-human natures, or more-than-human nature, as clearly exhibited in the deeper meaning of urbanism. We differentiate between the city (and its constituents) as the nature “outside” of humans (that is, a non-human nature) and the nature “inside” of humans (that is, human nature). In the same vein, the renowned urbanist Lewis Mumford (1895–1990) underlined the trans-physical nature of the city and its meaning beyond materiality. In his The Culture of Cities [31] (1970 [1938]), Mumford defined the city as a longue-durée phenomenon, a “point of maximum concentration for the power and culture of a community”. According to him, “the city is the form and symbol of an integrated social relationship; it is the seat of the temple, the market, the hall of justice, the academy of learning”, where “human experience is transformed into viable signs, symbols of conduct, systems of order” [31] (p. 104). In Mumford’s thought, the city is a multi-natured and multidimensional phenomenon that constitutes and is constituted by “a geographic plexus, an economic organization, an institutional process, a theatre of social action, and an aesthetic symbol of collective unity” [31] (p. 185).

Facing such complexity, in addition to the current ecological crisis, the philosophers Sean Esbjörn-Hargens and Michael Zimmerman, in their book Integral Ecology [32], have promoted the need for a deeper environmental awareness through interactive and transformative practices of the natural world. By emphasizing the conception of “oneness with nature”, based on direct experience with communities that deal with challenging ecological situations, they developed a method that discerns the variegated elements of complexity and stresses the importance of the spirit as both immanent and transcendent [32] (p. 488). Their integrated ecological approach of “oneness with nature” can serve as a source of inspiration for our understanding of contemporary urbanity in the sense that:

“Being one with nature” can refer to a particular kind of experience, a specific set of behaviors, a certain type of relationship with other beings, or a particular role within eco-social systems. In fact, an individual can be one with nature in all four terrains: behavior, experience, cultural, and systems. It is possible to feel one with nature but not act as one with nature. It is possible to be part of systems that are one with nature but a member of a culture that is not, and so on. We need a “tetra-mesh” understanding of “being one with nature”. It is not enough to have only a phenomenological experience of unity with the natural world.[32] (p. 277)

These definitions of the essence of the city and the essence of our environmental experience at present, and for the benefit of future generations, clearly portray the city as a complex dwelling machine with many interwoven parts laced with mechanisms, frictions, operations, functions, actors, and dynamics. The city is synchronously a physical and metaphysical entity, a combination of processes and products, actions and actors, coding and decoding, and indeed, a genre of all possibilities. The complexity of the city makes it amenable to excessively numerous and sometimes conflicting definitions, criteria, perspectives, agendas, concepts, and modes of enquiry. The city has been defined through demography, infrastructure, administration, politics, economy, society, culture, philosophy, history, geography, ideology, and ethics. It is a palimpsestic document of civilization and its historical layers.

In this article, we strive to redefine the city from the perspectives of its temporality and materiality, based on its foundation and founder myths in view of its urban ecologies. Archaeological and historical accounts are replete with evidence that all humans were hunter-gatherer beings until about 10,000 years ago when sedentary modes of life developed together with agriculture and agricultural methods. While cities were not normally created in history by segmentary societies of hunters and gatherers [33,34], sedentary hierarchical societies tended to create city-states—whose establishment myths included glorification of the king-cum-hunter tradition. For instance, scientific exploration reveals such examples in the first cities in the world, founded in southern Mesopotamia in around 7500 BCE as part of the Sumerian kingdom, including Eridu, Uruk, and Ur (later annexed by the Assyrian kingdom to the north). According to ancient scholars of the Near East, the militant hero of ancient times was usually a king and a hunter, and the western Levantine kings took a particular interest in hunting lions [35,36]. According to bible scholar Shmuel Abramski [37], the figure of Nimrod personifies the cultural history of the Mesopotamian monarchy. The first and principal mention of Nimrod in the Bible, for instance, not only places him in Mesopotamia but also assigns him great hunting prowess, kingship, and the building of a series of prominent regional cities (Genesis 10:8–12).

In the Babylonian creation myth Enūma eliš, Marduk emerges as the champion of the gods, who, with his bow, arrow, and net, kills enemy monster–soldiers. Through his heroism, he gains the status of king of the universe and then constructs the city of Babylon. Near Eastern scholars believe that not only might the biblical Nimrod be modeled after Marduk as a mighty hunter, ruler, and city-builder, but also that Marduk is a prototype of Ninurta, a divine warrior of the earlier Sumerian kingdom. In Akkadian and Sumerian myths, Ninurta kills a group of animals–monsters, becomes the patron of hunters and then organizes Sumer’s great urban infrastructure projects. In fact, Ninurta’s heroic military acts led to his role as the founding father of the Mesopotamian civilization [38].

3. Yoruba Cityscape Symbolisms of Hunting and Fishing

African cities were founded based on different landscape characteristics and resources that served as city-generating factors. Prominent among these factors were natural elements, such as topographical, hydrological, geological, ecological, floral, and faunal landscapes, as well as man-made city-generating factors, such as all means of transportation, economic opportunities, and socio-cultural elements [39]. Hills, rocks, slopes, and valleys are common topographical landscapes that facilitate city founding. Streams, rivers, lakes, lagoons, oceans, and seas are central to the formation of some other cities. All these landscapes and resources were culturally explored by highly significant actors to establish urban centers. Specifically, faunal and hydrological landscapes are associated with hunting and fishing, respectively. Here, we shall focus on the Yoruba homeland of Nigeria (often called “Yorubaland”)—a vast geo-cultural region mostly located in the country’s southwestern area, which experienced British colonial rule. This region comprises the vast majority of the Yoruba people in Africa, numbering close to 50 million—about 22% of Nigeria’s population and one of the continent’s largest ethnic groups [40].

The Yoruba homeland features mangrove forests, creeks, and coastal plains, as well as highlands towards the hinterland. Yoruba cities, which have exhibited a crystallized urban model since the thirteenth century [41,42,43], provide critical examples of hunting landscapes from time immemorial. According to the renowned American anthropologist William Russell Bascom (1912–1981), the Yoruba are “undoubtedly the most urban of all African peoples”, living in “large, dense, permanent settlements, based upon farming rather than upon industrialization the pattern of which is traditional rather than an outgrowth of acculturation” [44] (p. 446). Archaeological evidence [43] demonstrates that Yoruba urbanism predates European colonial influence and formal British colonial rule (1850–1960), with its origins traced to at least the eleventh century. The legendary founder of the Yoruba people, according to oral traditions, is Oduduwa, a semi-divine progenitor who was the founder of the Yoruba cradle city of Ile-Ife, from which a multiplicity of urban polities spread. Interestingly, a little-known documented myth of the Yoruba origins found in the late nineteenth century in the neighboring northern Sokoto sultanate—according to the early Yoruba historian Obadiah Johnson—assigns it to “the descendants of the Canaanites, of the tribe of Nimrod” [45] (p. 2).

In terms of urban configuration, the historical model of Yoruba cities featured certain repetitive elements such as a radial form with its hub as the Oba (king’s) palace, encircling massive mud walls with gates, wide main routes that extended from the palace to the gates, each leading to another Yoruba networked town, and main quarters with the homes of their respective heads facing these routes. Trajectories involving facets of hunting that were incorporated into the historical morphogenesis of these cities have been provided by the urbanist Afolabi Ojo [46]. According to Ojo, Yoruba traditional belief conceives the junction of two routes as both a converging and diverging point of good and evil, so that sacrifices for either placation or absolution were offered at junctions and central places. Additionally, the area behind the Oba palace was often reserved for a forest to provide space for the king’s recreational activity, which included small-scale hunting. During British colonial rule, expatriate officers sometimes used this forest reservation for recreational hunting together with the Oba. This reservation could also be used for collecting medicinal plants and for the Oba’s burial [46].

In contemporary times, hunting expeditions serve not only as a panacea for culturally opposed modernism but also as a means of reviving cultural sustainability. This practice is engaged in by some Yoruba elites, including the renowned Nobel Laureate Emeritus Professor Wole Soyinka [47], among many others. For instance, Soyinka once emphasized his hunting life and professional hunting skills in communication with a hunting and writing associate. He artfully drew the reader’s attention by directly asking, “Maybe you could also discreetly check for me on any traditional hunting groups. If you hear the name Asimotu in that zone, let me know. He was my night hunt companion of many years” (cited in [48], online).

Soyinka’s assertions testify to the efficacious sociability of hunting in maintaining long-term friendships, thus playing a significant role as a major contributor to the social capital of the Yoruba people. In an allegorical connection between heaven and earth, he frames hunting as a poetic myth bridging earthly terrestrial cityscapes and heavenly celestial abodes.

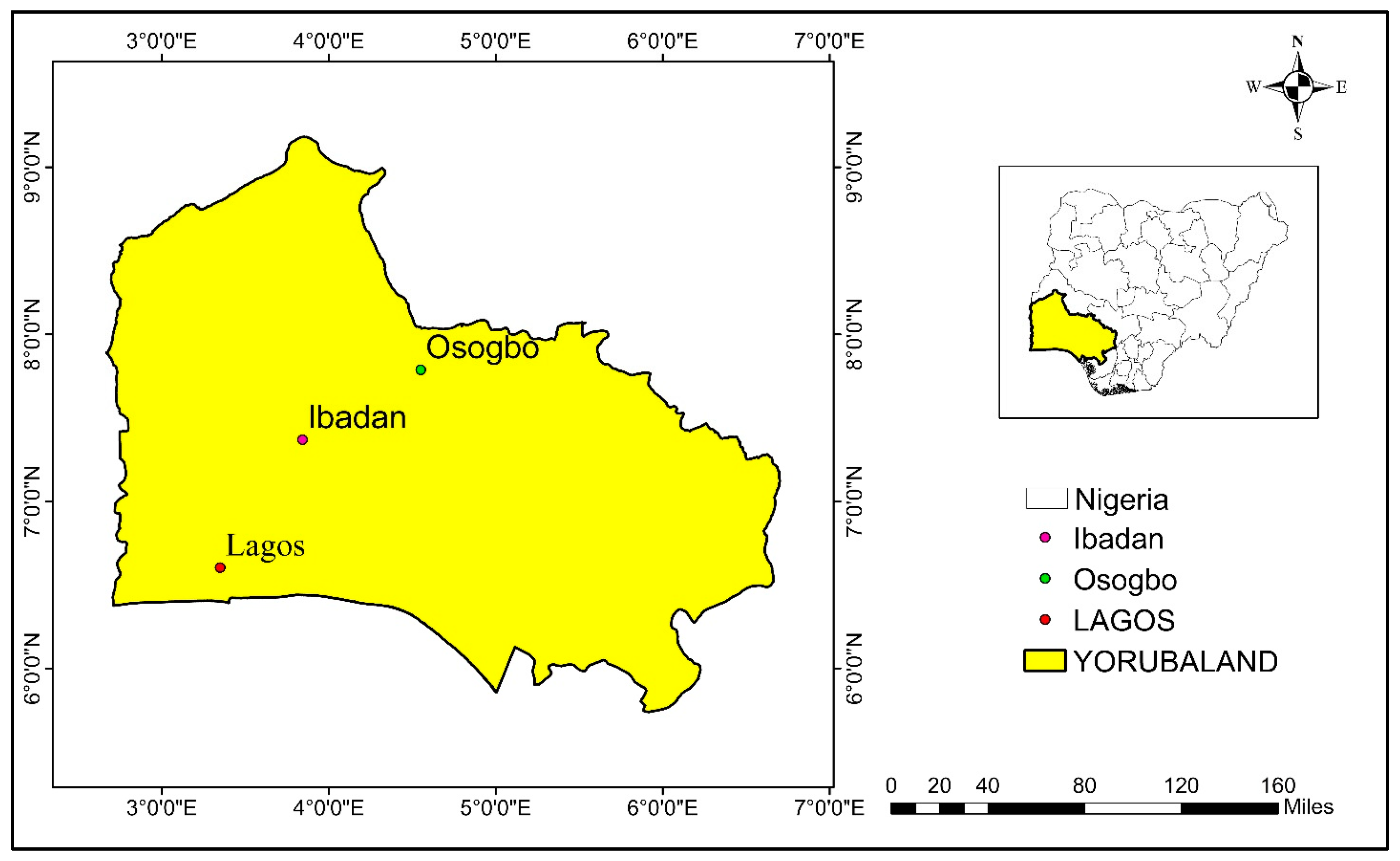

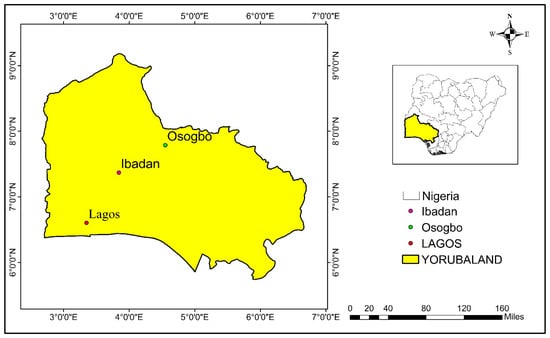

In the following, we will illustrate Yoruba’s eco-cultural claims as rooted in their urban development and patrimony, highlighting the role of hunters and fishers in the ecosystem and associated mythological imageries. This is done through three main examples: (a) The medium-sized city of Oṣogbo (about 796,000 residents in 2024). (b) The large-sized city of Ibadan (about 4,004,000 residents in 2024). (c) The megacity of Lagos (about 16,536,000 residents in 2024) [49] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Nigeria showing the three urban loci discussed in this article: Oṣogbo, Ibadan, and Lagos in the Yoruba homeland (Source: authors’ map).

3.1. Case I: A Former Hunting Landscape in Oṣogbo, Oṣun State Capital

The description of Yoruba cities as pre-colonial biocultural urban landscapes in Nigeria [50] is nowhere more evident than in Oṣogbo, which is a medium-sized city. Its archetypal status is due to the presence of the popular, pristine, natural, and socio-cultural landscape of the Oṣun Sacred Grove UNESCO World Heritage Site that lies at its urban core. Inscribed in 2005, it is one of only two such sites in Nigeria. To date, it globally represents the divinatory and cosmological system of the Yoruba nation. The grove, originally a hunting landscape, was transformed into a modern city. In terms of the city’s configuration to date, the grove constitutes a primary high-forest zone surprisingly located at the hub of an urban area. The animistic approach preserves the traditional socio-cultural heritage of the Yoruba people and enhances their social sustainability and urbanity. For instance, Figure 2 shows one of the traditional gateways along the route to the Oṣun Shrine in the Oṣun Grove, which exemplifies the animism of Yoruba traditional religions through eco-cultural symbolisms, and Figure 3 demonstrates that beyond physicality, animistic sculptural artworks define traditional religious territorialities separating “insiders” belonging to different traditional religious cults in the Grove from “outsiders” who are non-cult members. While the site’s use for global tourism allows visitors freedom of movement, there are spatio-temporal limitations on movement within the Grove dictated by belongingness to the cult systems housed there. This explains the complexities of social sustainability in cities founded by hunters and fishers. Based on an interview of a key informant regarding this green infrastructure, we shall trace in the following how this infrastructure became established, the nature of its mystical role in the worldview of the city’s residents, and how this role has been symbolically revived in the artwork presented there.

Figure 2.

A traditional gateway along the route to the Oṣun Shrine in the Oṣun Grove UNESCO World Heritage Site, Oṣogbo, Nigeria (authors’ photo).

Figure 3.

Animistic sculptural artworks in Oṣun Oṣogbo Grove UNESCO World Heritage Site, Oṣogbo, Nigeria (authors’ photo).

Our key informant for an interview in the Grove was Ms. Ayetigbo Helen Oluwaseun, a 45-year-old holder of a Bachelor of Science degree who recently served as the Chief Education Officer at the Oṣun Grove, Oṣogbo. When asked to elaborate on the history of Oṣun Sacred Grove in relation to Oṣogbo’s metropolitan area, she responded that the grove was founded about 600 years ago by Oguntimehin, a renowned elephant hunter from Ipole-Omu, a site near the town of Ilesha in Oṣun State, which faced water scarcity and was surrounded by hills and rocks. The hunter discovered Oṣun Sacred Grove’s rich water sources and convinced Ipole-Omu’s king to relocate their settlement. During the new settlement’s establishment, the community cleared bushes, accidentally felling a tree into the river. Following the incident, a strange voice from the river told them that they had broken all her [Oṣun] dye pots (field interview, June 2023). Ms. Oluwaseun explained that after consulting an oracle, the community learned about Oṣun, the river and sea deity residing in the water. The goddess allowed them to stay if they followed her instructions: to worship her for their settlement’s prosperity and to establish an annual festival for peace in their land. Due to this agreement between the sea goddess and the first settlers here, Oṣun is still annually worshiped in a festival that continues to this day. In relation to the clay sculptures, Ms. Oluwaseun continued:

The carvings [of Oṣun and other deities] were made with clay and red cement, that’s number one; number two, who made it? It was Aduni Olorisha, Susanne Wenger [c. 1915–2009]. Susanne Wenger came from Austria in her early thirties. She came with her husband Uli Bier; she came to Ede [a nearby town that lies along the Oṣun River], got the news of Oṣun from Ede and she came. Then she got attracted to Oṣun and she did not go back again. She divorced her husband Uli Bier. That one went back to Austria and then Susanne Wenger married an Oṣun man, Ayanshola Onilu [a drummer]. She was an artist. She was the one that did all the art work that you are seeing. She has people that worked with her in those days, they are still alive. Susanne Wenger is no more now, so those people that worked with her in those days they are the one renovating the art works that you are seeing here today.

We can draw conclusions from this popular myth of establishment, place-making, and place-keeping about the importance of the commemoration of the settlement’s founder-hunter, the natural resources that attracted the settlement’s pioneering community, and the ethos of the symbiosis with nature through the mediation and consent of metaphysical entities, which ensure the physical and moral wellbeing of the community. To preserve the foundational origin of the city etymologically, the Grove—as a unique Yoruba architectural site [51]—is often referred to as Oṣogbo (i.e., original city and locus of the entire cityscape), while all the intermediate and modern cityscapes are referred to as Ode-Oṣogbo (meaning “outside of Oṣogbo”).

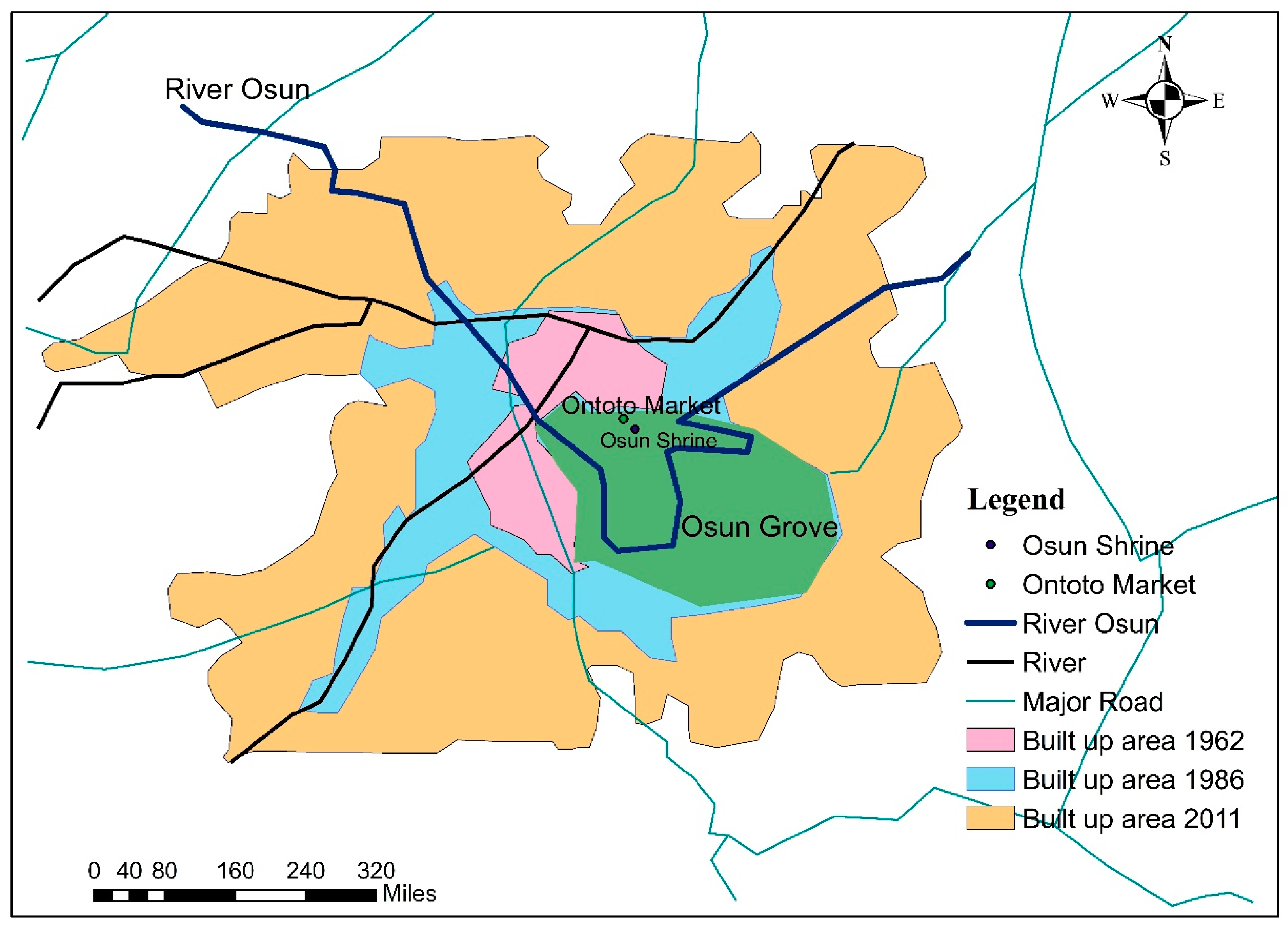

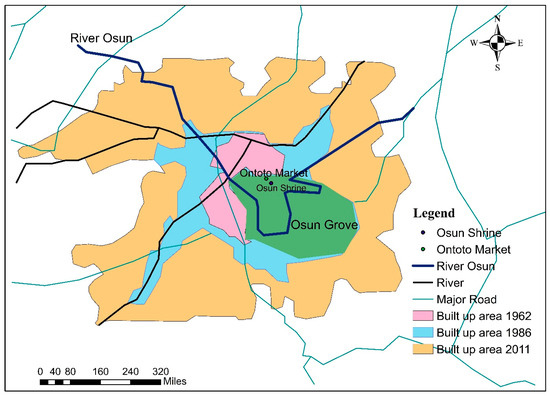

While the first settlement of the city at Ontoto market (a mythological market and the first market ever in Oṣogbo, in the Grove where humans and spirits are believed to have interacted) was founded in the grove in 1801, by 1911, the population had increased to 60,821. Continuous urbanization in Oṣogbo’s metropolitan area caused the population to increase to 649,600 by 2015, with attendant landscape changes (Figure 4). The space of the sacred grove has been persistently preserved despite demographic pressure, respected both by the city inhabitants and city authorities, along with the management frameworks of UNESCO and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) as a World Heritage Site. Yet, Oṣogbo’s rapid growth intensifies land use pressures, directly affecting the area around the site and its environmental conditions. Oṣun River has become increasingly polluted, while bush fires constantly threaten the grove. In their effort to improve the site’s place-keeping, Nigerian heritage authorities are involving active community members to assist with the challenge of ecological improvement, such as thorough cleaning and replanting endeavors [52]. Economic gains from the annual festival are also channeled towards conservation work. Plastic and heavy metal pollution is especially high, in addition to pollution due to surrounding mining activities [53]. As will be emphasized in Section 4 designing measures to meet these environmental challenges not only calls for more inclusive and optimized urban planning and waste management processes but necessitates an examination of the human-cultural habits and practices that lie at the heart of the social sustainability agenda.

Figure 4.

Map of Oṣogbo in relation to its urban growth showing locations of Osun Grove, Osun Shrine, and Ontoto Market within the Grove and River Osun (Source: author’s map adapted from [39], p. 800).

3.2. Case II: Former Hunting Forest Landscapes in Ibadan, the Erstwhile Capital of Nigeria’s Western Region

Ibadan is one of the largest, most populous, and fastest-growing urban centers in sub-Saharan Africa (after Cairo, Lagos, and Kinshasa), with over four million residents in its total metropolitan area today. A prominent point of transit between the coastal region and the inland areas and the former administrative center of the British colonial Western Region, Ibadan’s traditional character in terms of the configuration of the city epitomizes the zenith of pre-colonial and early-colonial urban development in Nigeria. The first television station in the subcontinent was established in Ibadan in 1959 and is called the Western Nigerian Television. Its 25-story, 105 m tall “Cocoa House”, completed in 1965, was the first skyscraper in Africa and the tallest for many years. These achievements were promoted by late chief and statesman Obafemi Awolowo. Ibadan is also home to the first University in Nigeria, the University of Ibadan, which was established in 1948 as a College of the University of London.

Ibadan emerged in three successions after the previous two settlements involving forest habitation had failed. The search for a safe place to settle during the three successions was tied to the great political instability in the Yoruba country as a consequence of the long-lasting slave trade. In the third succession (up to the present), the city was established by a great hunter–warrior, Lagelu, in around 1750 and became a traditional military headquarters serving as a war camp in around 1829, at Kudeti, a deserted Egba village [54]. The historically dominant military conquest of Ibadan attests to cooperation between the allied Yoruba army, made up of inhabitants from their various city-states (such as Ife, Oyo) and of affiliated groups (such as Ijebu, Egba). By 1840, the city had grown so much that it dominated the military, political, and economic landscapes of the Yoruba nation [54]. Parts of the city’s protective mud walls from that time still survive to this day. The political system was well suited to the evolving military expansion dominated by frontline warriors and hunters, as the population of polycentric and expansive Ibadan had already grown to 60,000 by 1851—the year of the British occupation of the region.

As the urbanization process continued, by 1890, Ibadan’s mud walls enclosed a population of at least 120,000 people. This period marked a transition landscape from the pre-colonial to the colonial periods in relation to ecology and infrastructure. By 1893, Ibadan had become a British Protectorate, accelerating the influence of colonial rule on the urbanization process. By 1911, the city’s population reached 175,000, and the landscape was highly socially classified, expressing the nature of power relations and their exertion over space. The “westernized” modern landscape of the period suggests the power of “political landscapes” to transform the entire cityscape into “landscapes of politics”—where colonial power relations and socio-cultural identities were fashioned through mundane engagements with the urban “nature” [55].

This process of landscape change led to the establishment of Ibadan as the administrative headquarters of the British Western Region of Nigeria in 1946, with its attendant exclusionary and centripetal urbanization forces. In 1960, Nigeria became independent from British colonial rule. By 2020, the population of the booming city of Ibadan had grown to about four million, as noted earlier. As an exemplary case of oral history and accumulated place-related memories and socio-cultural identities, we spoke with Baba Aboke (head traditional priest), Chief Fashola Ifamapo, the Aboke of Oke-Ibadan (Ibadan Hills), about the historical layers of Ibadan. According to him, Oke-Ibadan is not a land or a deity that came into existence by chance. Rather, when Lagelu started his journey from Ile-Ife, he also sought to establish his own land or community. Ibadan’s original name was Eba-odan (“by the edge of the meadow”), later simplified to Ibadan for easier pronunciation. After Ife, Legalu first settled at Iparra forest after seeking the gods’ approval for this settlement through Akati, an Ife native doctor. The gods demanded a human sacrifice in return for the community’s growth and prosperity there, but Lagelu decided to move from Iparra to Awotan forest, where the gods made the same demand. After making the sacrifice and settling in Awotan forest, the community discovered that the site’s topography was unsafe, with people falling down the hill and dying as a result. They then decided to move yet again, this time from Awotan to the site of Oke-Ibadan [today’s Eleyele area] (field interview, February 2024). The Aboke of Oke-Ibadan continued the narrative:

That was how the story of Oke-Ibadan came to be. We came from Ife, our tribe is from the house of Degelu in Ife. After they started worshipping Oke-Ibadan, the Ibadan people never lost a war, although they fought a lot of wars then and too many lives were always lost. So that gave birth to a yearly festival where a cow is sacrificed instead of a human sacrifice, and any time [that] a new king takes over the throne, it is a must for him to sacrifice a cow to Oke-Ibadan annually. You see that soap you saw downstairs; it is made here in Oke-Ibadan’s shrine from specific herbs found here. This soap is used whenever there is an outbreak of skin disease or if the Sanpona deity [the smallpox deity] attacks a person, this soap is what is used to cure the outbreak and disease. People come from far and wide to get this soap, because it can only be found here in Oke-Ibadan. It also heals people with leprosy and damaged skin cells and body parts. Oke-Ibadan is not a troublesome deity, in fact it is the hope of the hopeless. Many people who are jobless or barren come here to worship Oke-Ibadan and they get what they desire. It is known as a rescuer of the people (Agbomola). The only taboo is that during the yearly festival there should not be any smoke especially from cooking with the use of firewood, even if there has been a smoke fire, water must be poured and the smoke extinguished before the festival starts. That’s its taboo.

To emphasize the linkage between Ibadan and Ile-Ife, the traditional Yoruba religious capital city, Chief Ifamapo highlighted that his lineage originates from the house of Degelu near the king’s palace in Ile-Ife. According to him, they moved from Ife to Awotan, and it remains important to appease Oke-Ibadan at Awotan’s shrine annually before the start of the festival. For this reason, the current Ibadan is called the third Ibadan. The second Ibadan was the settlement at Awotan Hills, while the first was at Iparra Forest. Iparra also has a shrine located near Awotan at the Oja Oba axis, and people are sent there to complete the sacrifice before the annual festival (field interview, February 2024). This interview, which highlights an urban (oral) history not yet fully documented in English, reveals the holistic relationship (“one with nature”) between indigenous groups and natural resources, as well as the spiritual connection between humans and nature during the place-making process. While searching for a safe place for settlement, both topographically and religiously (permission from the gods), the forested hills in today’s Ibadan area were mapped for settlement but ultimately rejected for the same topographical or religious reasons (the first and second Ibadan). Eventually, it was decided to settle in the plain within closed mud walls (the third Ibadan), but the eco-cultural connection with the two previous forest loci has been preserved to this day.

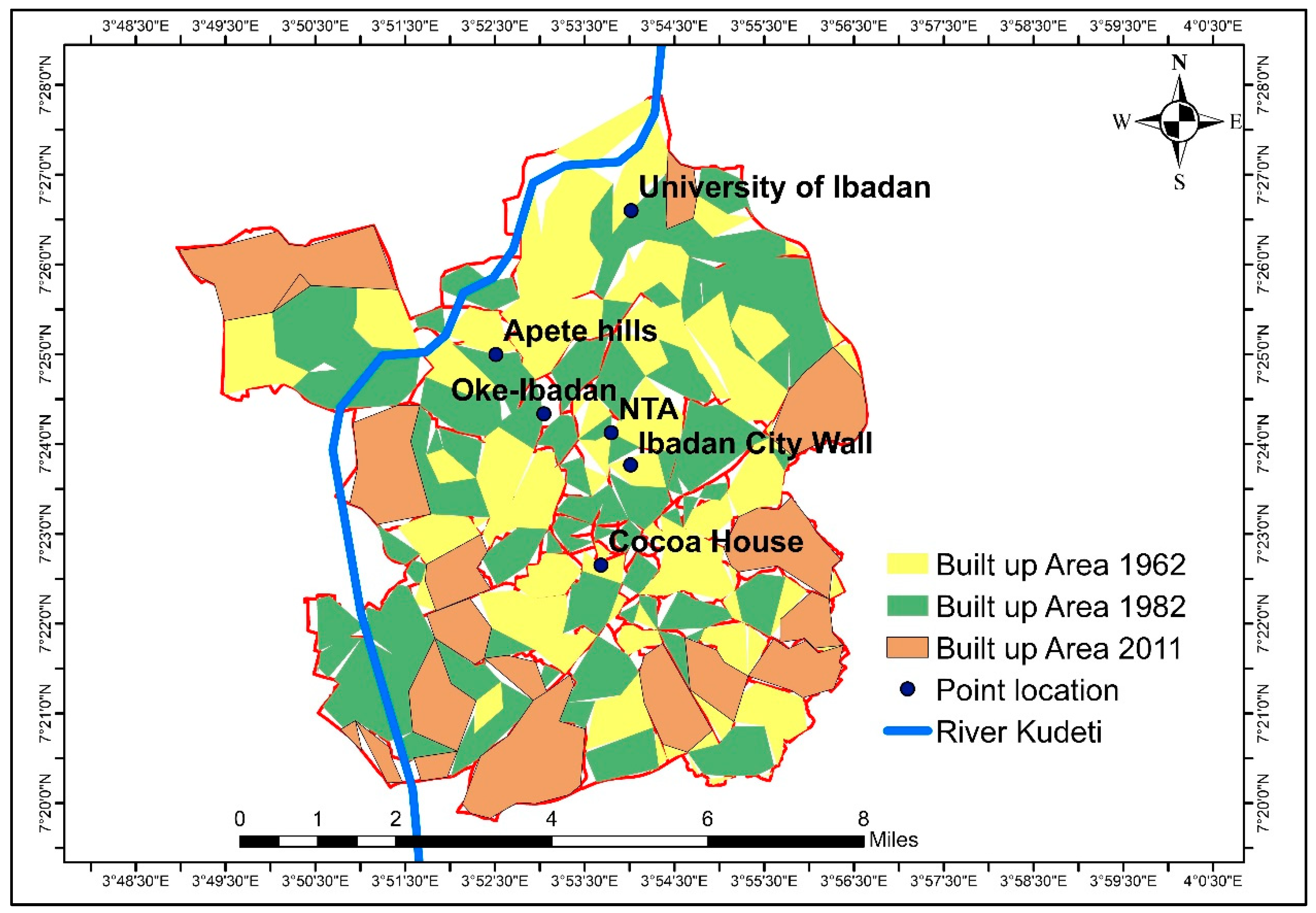

This connection is based on a continued (re-)evaluation of the natural resources, places of worship, and ethno-medicinal herbal practices of the founding fathers across generations. It is also based on an ongoing commemoration and societal persistence of the founding lineages to this day. A ceremonial dimension is also present, characterized by the pursuit of designated festivals and holidays, similar to the valorization of the warrior–hunters as a site-connected social elite (also in the more brutal or “dark” sense of these occupations) during times of significant physical and environmental instability in Yoruba land between the mid-eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries. Aside from the narrative landscape, Figure 5 depicts the physical landscape of Awotan forest in Ibadan, a former hunting ground in the Apete hills. The neighborhood is currently expanding due to urban land use pressure while continuing to contribute to social sustainability by preserving the socio-cultural heritage of Ibadan’s founding by the great hunter–warrior hero Lagelu. Figure 6, which depicts another sector of Awotan forest in Ibadan, points to the ongoing desacralization from traditional religious uses to Christianity, driven by unprecedented land-use pressures and modern influences.

Figure 5.

Awotan forest, former landscape of hunting at Apete hills, Ibadan, Nigeria (authors’ photo).

Figure 6.

Another view of Apete hills, Awotan forest, Ibadan, Nigeria (authors’ photo).

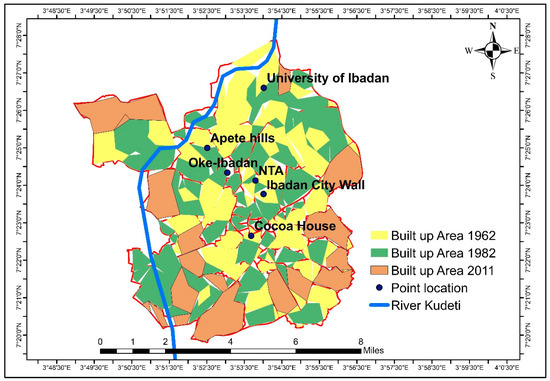

As a relatively new city in comparison to many other Yoruba urban centers (as noted, mostly from after 1829), the booming city of Ibadan is strong in terms of place-making and eco-cultural heritage. However, the extent and quality of its greenspaces are highly threatened by its status as one of the most populous cities on a regional, subcontinental scale (Figure 7). Its location at the fringe of the rainforest (from which it earned its toponym) has historically contributed to its role as a trading center for agricultural crops and goods from both forest and savannah areas, enhanced by abundant industrial and economic functions. In fact, Ibadan is currently considered the third most affordable city to live in in Nigeria [56]. Consequently, Ibadan’s ecosystem has been damaged by human-induced influences through land use and waste effluent discharges, particularly at Awotan and the aforementioned heritage sites. Recent studies have exposed serious degradation in terms of pollutants (solid, liquid, and gas), fuelwood harvesting, indiscriminate waste dumping, sand excavation, and housing construction, among other factors [57,58]. An analysis of landcover developments in Ibadan shows that between 1987 and 2019, water sources decreased from 1.6 km2 to 1.3 km2, greenspaces decreased from 24.8 km2 to 14.9 km2, and residential sprawl increased from 8.9 km2 to 20.1 km2 [57]. Here, too, there is a need to develop comprehensive regulative measures based on both strategies to protect the existing natural reservoirs and public eco-cultural education for heritage valorization and preservation (see Section 4).

Figure 7.

Map of Ibadan in relation to its urban growth, showing locations of Oke-Ibadan, Apete Hills, Cocoa House, Nigerian Television Association (formerly, Western Nigerian Television), University of Ibadan (formerly, College of University of London), and River Kudeti (Source: Authors’ map).

3.3. Case III: The Longevity of Fishing Landscape in Lagos, the Former National Capital of Nigeria

According to Yoruba oral traditions, Lagos was founded by fishers (and farmers) of the Awori sub-group on a small island on the Atlantic coast in the pre-colonial era of the slave trade, in around the sixteenth century. According to the early (1914) Yoruba historian John Losi [59], “The first settlers dwelt at Iṣeri, on the River Ogun about twenty miles from Lagos. The first man that built Iṣeri and settled there […] was a hunter, named Ogunfunminire, ‘the god of iron has given me success.’ He was of the royal family of Ile-Ife” [59] (p. 1). The city of Lagos was “born” from the distinct but complementary interaction between land (landscape) and ocean (waterscape) systems. This binary system has remained symbolic of the urban systems and landscapes from the city’s inception to the present day. The initially uni-cultural and agricultural Lagos Island was first visited by the Portuguese explorer Rui de Sequeria in 1472, who arrived via the Atlantic waterways that “landed” at this coastal settlement. Portuguese traders later arrived and named the settlement “Oko”, “Onim”, and “Lagos”, meaning “lakes” [60]. They were not aware that they were re-establishing the existing foundation of a future world-renowned urban landscape and conurbation of global city systems.

This landscape of fishing underwent a transformation when it was annexed and became the military base of the Benin Empire in the years 1578–1606 [61]. In the years 1606–1821, Lagos became the most popular slave port of the West African Slave Coast. The slave port of Lagos became transnational, often frequented by Portuguese, American, French, and Cuban slave ships. Fujita and Mori [62] (1996) highlighted the irreversible importance of ports in the evolution of major coastal cities across the globe, even after their initial advantage of water access had become less relevant. In this respect of an evolutionary model, Lagos is not only prominent but very unique. During this period, in 1600, the “contrasting urbanism” of Lagos was evidenced by the internal migration of the Ijebu and Ilaje fishers from the hinterland, in addition to the Awori, who settled at Idumagbo Lagoon area in the middle of the island. By the early nineteenth century, European merchants had established a presence in the southern part of the island and offshore, on the mainland at Ebute-Metta [61]. This land-ocean and ethno-racial binary reflects the endogamous and exogamous power relations of settlement agglomeration.

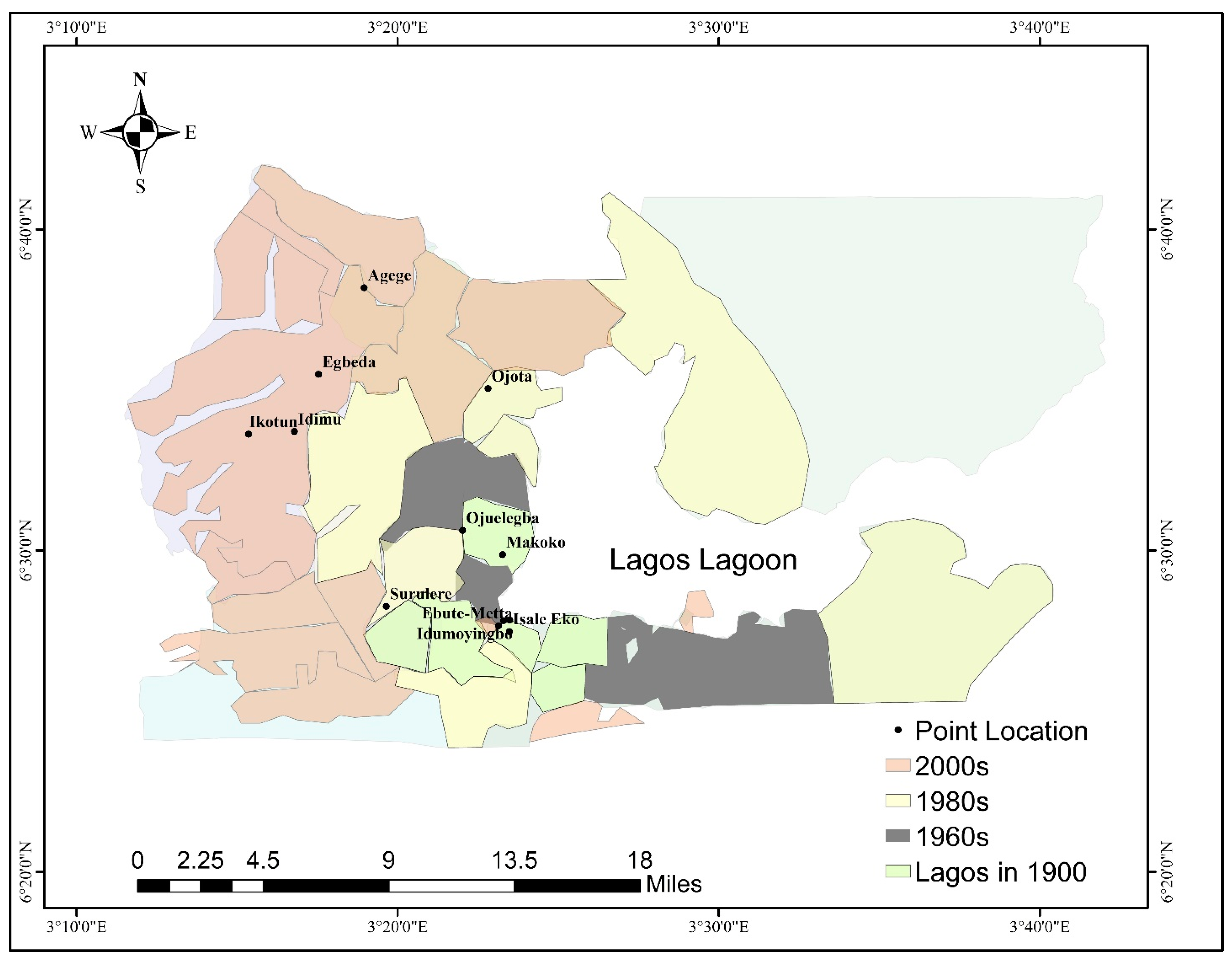

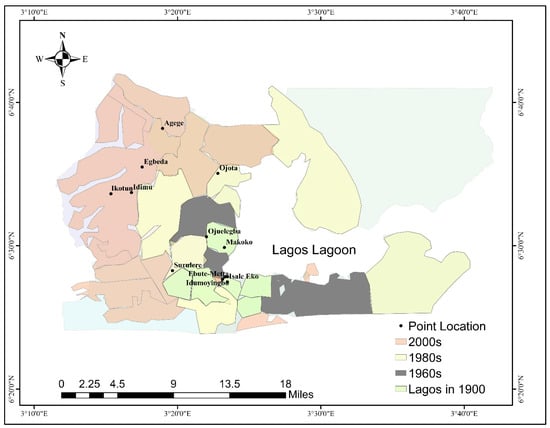

In complicity with the local monarchical system of governance that had gradually developed on the island as the main beneficiary of the Atlantic slave trade, the expatriate slave traders and merchants continued to dominate the population of Lagos Island until the anti-slavery treaties were implemented. This was enforced through the Royal Constabulary Force and later the West African Frontier Force. This period led to the next binary of contrasting political systems of colonial rule when the British proclaimed a consulate over Lagos in 1851 [63]. The landscape evolution of the pre-colonial Lagos between 1600 and 1851 was confined to Lagos Island and part of Ebute-Metta, separated by the Lagos Lagoon. It presented striking contrasting systems of change, from the ecological use of fishing and agriculture to a semi-urban landscape, from sea-scape navigation to land-based economic destinations, from a bio/agro-economy to a human economy based on the slave trade, from a mono-cultural to a poly-cultural socio-economic landscape, i.e., from mono-nativity to poly-ethnicity, from farming spaces to trading places, from localized economic activities to global wealth. By 1886, the population of Lagos had increased to 25,083, reaching 41,850 by 1901. With unprecedented urbanization, industrialization, and economic and colonial expansion, its population grew to 271,800 by 1952 [64]. Currently, the population of the Lagos metropolis and the entire Lagos State exceeds 21 million (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Map of Lagos in relation to its urban growth showing locations mentioned in this section: of Ebute-Metta, Lagos Island (Enu-Owa, Isale Eko, Idumoyinbo, Oba Palace), Makoko, Surulere, Ojuelegba, Ojota, Egbeda, Idimu, Agege, and Ikotun (Source: Authors’ map).

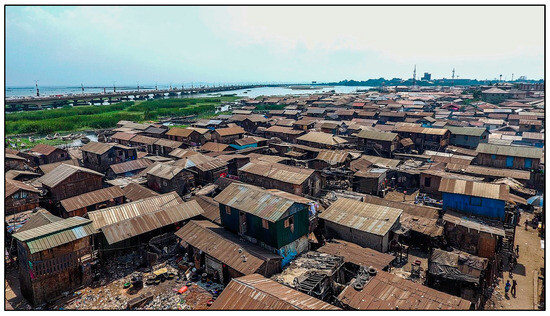

Despite industrialization, Lagos remains an important fishing landscape along the West African Coast. For instance, the extra-formal Makoko quarter of Lagos, designated as a slum, is a 200-year-old fishing settlement built on stilts on the banks of the Lagos Lagoon in Nigeria. About 100,000 people currently live in expanding Makoko, most of whom are fishers [65]. Figure 9 illustrates Makoko’s established terrestrial and aquatic ecological units. Founded by fishers over 200 years ago, fishing activities continue to define its urbanity today, too, despite the settlement’s unhygienic environmental conditions, poor housing, communication infrastructure-laden skylines, and persistent land use pressures. During our interview with a marine ecologist at the University of Lagos, near Lagos Lagoon and the Makoko area, he described one of the current fishing methods of Makoko residents in the Lagos Lagoon, clearly emphasizing its sustainability in terms of the production chain. According to him, Makoko’s fishers install fish culture (Acadja) in the water using fish aggregating devices that operate as a natural harbor culture, allowing fish to stay longer without additional feed. These structures attract organisms preferred by the small fish that try to avoid the big ones. The fishers then return to harvest the fish, but they do not capture all of them, enabling sustainable growth of the fish culture (interview, August 2023).

Figure 9.

An aerial view of the Makoko urban extra-formal settlement in Lagos, Nigeria (photo in public domain, Wikimedia Commons).

These intricate layers of place-making and place-keeping operations have been embedded in Lagos’s environmental cognition and spiritualization of nature. These layers of heritage “archaeology” are inscribed on the city neighborhood environments, among other forms, as shrines dedicated to certain gods and goddesses. These socio-cultural practices have persisted despite the forces of urbanization, civilization, and modernization. All Lagos areas, from downtown to suburban, have retained these cultural ecological identities to date. Even though urban developments have led to the desacralization of the groves’ foregrounds of Lagos shrines through apparently democratic urban governance, they are deliberately left out as developments are designed to include them. Consequently, they are still in existence at roundabouts and under urban tropical trees in Surulere (formerly Abule Esu/Elegba), Lagos Island, Ojuelegba, Ojota, Egbeda, Idimu, Agege, and Ikotun. As French sociologist Christian Topalov observes in his edited collection Les Divisions de la Ville, which analyzes the intertwining of modern and pre-modern layers in the city: “Beneath the prominent simplicity of the spatial divisions of modern governance, the traces of ancient institutions can be perceived, the placement of the past within the present, and the spatial claims of groups” [66] (p. 1, authors’ translation).

The multi-nuclei urbanization of Lagos results in these communities having separate shrines at the entrance of each locus, as the Yorubas believe that the shrines are sources of protection for the inhabitants. During an interview conducted at the Enu-Owa site in the heart of Lagos Island, some facts emerged about the ontological connections between ecological nature and cultural practices in Yoruba cities. The Enu-Owa Square and groves are the ritual center of Old Lagos. Its shrines function in the cult power relations of the Lagos chieftaincy institution. Enu-Owa, located in the Isale Eko community, is very central to any discourse on Lagos, being as old as Lagos itself. Isale Eko is the first settled ancestral and indigenous area in Lagos, with many traditional cultures related to the Lagos kingship institution. In relation to the kingship institution and how it is ecologically inscribed on Enu-Owa square and Isale Eko in general, an interviewee, Mr. Mudashiru Dosumu, an over-60-years old Yoruba and indigene of Isale Eko, submitted that:

The majority of the houses in Isale Eko are ancestral houses, full of cultural and traditional collections […] Isale Eko is a place where the palace of the Oba of Lagos is situated and the majority of the traditional White Cap Chiefs [the pre-colonial agency of landlords] have their palaces; either Akarigbere, Abagbon, Ogalade or the Idejo [these chiefs’ titles]. The Idejo traditional White Cap Chiefs are the land owners. The Akarigbere migrated from Benin and settled in Lagos as far back as 1630 and the Abagbon-s guide and protect Isale Eko community; while the Ogalade-s are in charge of the spiritual and traditional activities.

The traditional and cultural ecosystem services of Enu-Owa are unique and numerous. The Akoko tree at Enu-Owa is used for the coronation of kings and chiefs in Lagos, as in all traditional Yoruba kingship institutions (Figure 10). Enu-Owa’s site houses Odiyan shrine, the Oluṣogbo enclave, and the Ojuolobun tree, with adherent practices of traditional Yoruba cult religions. These eco-cultural sites are distinguished by traditional sacredness from profane spaces of the city for everyday use. The centrality of these urban shrines is evident in the performance of every traditional activity in Lagos at Ojuolobun. Figure 11 depicts Ojuolobun shrine as one of the spatial identities of Enu-Owa’s urban core and Lagos at large. Its persistence in its original “crude” form as a traditional entity within a modernized urban setting demonstrates the power of religion in shaping urban forms. The only traditional market in Lagos is located at Enu-Owa, which shares this overall spatial complex that includes cultural and ecological sites. This spatial complex makes Enu-Owa the traditional spiritual headquarters of Lagos, its ancestral home and heritage site. It is an indigenous area with heritage artifacts over 400 years old. In addition, a significant neighborhood at Enu-Owa called Idumoyinbo is where the European explorers first visited in 1704 during the reign of Oba (King) Akinsemoyin. These antecedents position Isale Eko and Enu-Owa, in particular, as traditional, socio-political, economic, and educational hotspots of Lagos. Moreover, the economic prowess is still premised upon commercial activities, fishing in particular. Given the aquatic ecosystem of the adjacent Lagos Lagoon, fishing is the predominant ecosystem service in Enu-Owa and Isale Eko in general.

Figure 10.

Akoko Tree at Enu-Owa, Isale Eko, Lagos, Nigeria; its leaves are used in crowning coronation ceremonies for Lagos Monarchs and traditional chieftaincy titles, contributing to social sustainability (authors’ photo).

Figure 11.

Ojuolobun shrine at Enu-Owa, Isale Eko, Lagos (authors’ photo).

In his narrative of the Lagos evolution to unpack the factors of the city’s settlement pattern, the interviewee, Mr. Mudashiru Dosumu, whose surname is often assigned to the Oba of Lagos since the 1851 British Consulate intervention there, noted a cultural connection between Enu-Owa in Lagos and Enu-Owa in Ile-Ife, reflecting the cultural morphology of Yoruba cities in general. According to Dosumu, “The first settlers in Lagos, the Awori-s, stayed at Iddo [a then semi-island created by lagoons within Lagos Island], but people from Benin moved down to this area. So, Enu-Owa is a very reserved area and if you go to Ile-Ife, we have Enu-Owa [there] too, where kings and chieftaincy installations take place with Akoko leaves.”. Thus, just like Enu-Owa at Ile-Ife, the Enu-Owa in Lagos hosts the Ogun Shrine, Odiyon Shrine, and Enu Owa Shrine, which are essential components of traditional Yoruba religious pantheons. The Ogun Shrine serves for both worship and the coronation of the Eletu Odibo family chieftaincy title. The Enu-Owa Mosque and King’s Church are also sacred spaces in this city core, which is characteristic of other Yoruba city cores within Yoruba urban configuration modalities.

The physical-cum-narrative landscapes of the inner city of Lagos, viewed through a longue durée perspective of past and present, reveal the “archaeological” layers of place-making and the contemporary place-keeping challenges. Despite consumerism and neoliberalism, the indigenes of Isale-Eko continue to give prominent attention to religions. The continuity and recent revival of autochthonous (pre-Christian and pre-Islamic) religions persist on both the spatial and symbolic levels [67]. Yet, this socio-cultural phenomenon coincides with several environmental challenges. Some of these ecological fragilities are similar to those in Oṣogbo and Ibadan, such as accelerated urban expansion and human congestion. Others are site-specific, such as Lagos Island’s low-lying area’s vulnerability to sea level rise and flooding [68]. Recognizing that Yoruba cityscapes are an ongoing product of both cultural heritage and ecological modalities, each reciprocally designed by the other, calls for the formulation of strategies to meet these challenges. In the next concluding section, we have attempted to frame such strategies as recommendations and reflections for a sustainable urban policy design to the extent that this is feasible in the context of Nigeria’s southwestern region.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations: Designing an Urban Policy of Eco-Social Sustainability through the Hunting Patrimony

The traditional historical narratives highlighted here provide clear indications that hunters and fishers played significant founding roles in Yoruba urbanism. The traditional urban modalities and configurations analyzed in this article are intertwined with the metaphysical practices etched on the cityscapes, manifested in significant physical and symbolic embodiments. Yoruba urbanities and narrative landscapes, far from being merely pre-colonial history, are founded on a cultural lifestyle that stubbornly persists to this day. Today, this West African urbanity is defined by the following: ethno-medicinal herbal practices; sites of worship of deities and traditional cult systems; landscape signification; forest hunting reservations and hunting festivals, practices, and mythologies; and past and modern artistic expressions, such as hunters’ music (Ijala-Ode), historic literary genres (e.g., popular songs and epics), and traditional and fine art that pays homage to hunters and fishers.

In alignment with UN SDG 2030 Goal 11.4, this article explored the lived heritage of Yoruba communities in three urban loci through an environmental lens. This was done in order to leverage the cultural assets of these communities to design a more socially sustainable urban policy centered on place-making and place-keeping. By focusing on reconnections such as the re-sacralization of desacralized hunting landscapes, revival of cultural ideologies, decolonization from occidental paradigms, and re-definition of urbanism in light of African perspectives and site-related contexts, this study enriches our understanding of the interconnections between environmental and social sustainability.

The study demonstrates that hunting remains integral to the cultural practices of Yoruba urban imageries, where hunters and fishers remain key actors in nature conservation, contributing to the socio-cultural capital, economic sustainability, and urban security of both man-made and natural architectures. In fact, hunting activity and hunters-cum-city-builders commemoration extend beyond Yoruba communities to other West African nations, such as the Wolof and the Malinke (Mandingue), warranting further investigation of these cultural capitals as well. In this light, the importance of consolidating urban social sustainability through the potential usability of such lived and oral patrimonies is underscored by Fadamiro and Adedeji. According to them, traditional conservation strategies such as mythological approaches and legal frameworks should be rigorously enforced to ensure sustainable conservation of the landscapes. While exploring the tourism potentials of the sites, efforts should be made to minimize the negative ecological impacts of tourism activities despite the economic, political, social, and cultural benefits [69] (p. 27). Moreover, Fadamiro and Adedeji argue that to achieve optimal [nature] conservation results, it is crucial to involve local communities in the development, promulgation, and implementation of legal frameworks for the [hunting] cultural landscape sites [69] (p. 27). This approach allows for the integration of mythological strategies into the legal framework, enhancing the strengths of both, while neutralizing their inherent weaknesses. This can be achievable through a careful review of existing laws, establishing committees that include autochthonous active residents, and soliciting memoranda.

On the whole, there is a need to devise strategies related to place-making and place-keeping to reconnect with these traditional value systems in rapidly westernizing sub-Saharan Africa. These strategies should include the following: enhancing community awareness of cultural heritage and re-sacralizing desacralized landscapes of hunting and fishing; revitalizing cultural ideologies through public events and educational activities; and re-evaluating Indigenous social capital for cultural decolonization and re-definition of contextualized urbanisms in the subcontinent, despite globalization. This study exemplified the crucial role of qualitative research in uncovering bottom-up community narratives, socio-environmental ethos and values, and cultural landscapes. Such urban policy vision should be supported by national and civil society stakeholders with a professional affinity to and interest in cultural heritage, as well as by community economic and educational cooperation for place-keeping and place-storytelling.

At the same time, addressing the constant reduction of green and open urban spaces in sub-Saharan African cities due to uncontrolled urbanization, natural disasters, and man-made air, land, and water pollution requires an integrated approach beyond a culture-based one. Recognizing heritage sites, enhancing cooperation between different planning and policy agencies at the state and municipal levels, identifying stakeholders, and establishing a digital database to synchronize quantitative tests of environmental degradation with the intangible characteristics of the urban greenspaces can overcome the fragility that characterizes many urban administrations in the subcontinent. Learning from other countries experiences in heritage management and place-keeping with an emphasis on South–South cooperation could be productive and feasible. For example, China is leveraging landscape cultural heritage through pioneering digital projects (beyond the digital management tools provided by UNESCO). This is accomplished through smart centralization of the information for each heritage landscape, incorporating variable data, including “soft”, intangible, and culture-dependent data as open source [70,71]. Similarly, laying an infrastructure for a multidisciplinary management system based on multidisciplinary knowledge of heritage sites in Yoruba cities can synchronize data in environmental studies, urban planning, and cultural capital. Such a product constitutes a relatively “low-hanging fruit” that would significantly improve the long-term maintenance and sustainability prospects of the inner-city greenspaces while constantly monitoring data of various policy aspects and facilitating learning. It could be initially tested in sites already receiving considerable ecological and cultural research attention at the local, national, and international levels and that are already benefiting from UNESCO’s professional support, such as Oṣun-Oṣogbo Sacred Grove.

By highlighting Yoruba cityscapes of hunting and fishing, the study broadens the mainstream geographical scope of urban social sustainability research by including “off the map” spatialities, which receive less attention in the relevant historiography. Expanding on the rich imageries, memories, and morphogenesis of Yoruba urbanities à longue durée, we seek a more nuanced understanding of the “Glocal” and its common and particular components. We believe that more attention to qualitative, “down to earth” studies (inspired by [72]) would enrich urban social sustainability studies with relevance, contextuality, and meaning. By tying together cities’ pasts and presenting in-thinking of their more sustainable futures, we aim to nourish (and decolonize) urban policy making. This approach would help bridge the current geographical division between urban “theory” (typically generated in the West/Northern hemisphere) and “development” (often projected onto the Southern hemisphere, where urban realities are often disconnected from “theory” and where historicities and ecologies are still less well-known). It will also enable feasible improvements in quality of life and wellbeing in the present and near future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.A. and L.B.; Investigation, J.A.A. and L.B.; Writing—original draft, J.A.A. and L.B.; Visualization, J.A.A. and L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UN-HABITAT. The State of African Cities 2014: Re-Imagining Sustainable Urban Transitions; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hoornweg, D.; Pope, K. Population Predictions for the World’s Largest Cities in the 21st Century. Environ. Urban. 2017, 29, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Pierce, J.; Martin, D.; Murphy, J. Relational Place-making: The Networked Politics of Place. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2011, 36, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Place and Place-making in Cities: A Global Perspective. Plan. Theory Pract. 2010, 11, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattijssen, T.; van der Jagt, A.; Buijs, A.; Elands, B.; Erlwein, S.; Lafortezza, R. The Long-term Prospects of Citizens Managing Urban Green Space: From Place-making to Place-keeping? Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 26, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salizzoni, E.; Pérez-Campaña, R. Design for Biodiverse Urban Landscapes: Connecting Place-making to Place-keeping. Ri-Vista Res. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 17, 130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Priya, A. Case Study Methodology of Qualitative Research: Key Attributes and Navigating the Conundrums in its Application. Sociol. Bull. 2021, 70, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansina, J. Once upon a Time: Oral Traditions as History in Africa. Daedalus 1971, 100, 442–468. [Google Scholar]

- Manyane, R. Centuries-Long African Oral Traditions and History: Revisiting the Debate. J. Afr. Hist. Archaeol. Tour. 2024, 2, 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Potteiger, M.; Purinton, J. Landscape Narratives: Design Practices for Telling Stories; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.S.; Fiore, J.M. Landscape as Narrative, Narrative as Landscape. Stud. Am. Indian Lit. 2010, 22, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Chiou, S.; Wang, F. On the Sustainability of Local Cultural Heritage Based on the Landscape Narrative: A Case Study of Historic Site of Qing Yan Yuan, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: Westport, CT, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C.O. The Morphology of Landscape. Univ. Calif. Publ. Geogr. 1925, 2, 19–53. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, J.; Duncan, N. Recreating the Landscape. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1988, 6, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A. On Cultural Landscapes. Tradit. Dwell. Settl. Rev. 1992, 3, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hough, M. Cities and Natural Processes; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, C. Introduction: Identity, Place, Landscape and Heritage. J. Mater. Cult. 2006, 11, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapagain, N. Heritage Conservation in Nepal: Policies, Stakeholders and Challenges. Himal. Res. Pap. 2008, 26, 37. Available online: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nsc_research/26 (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Han, F. World Heritage Cultural Landscapes: An Old or a New Concept for China? Built Herit. 2018, 2, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, L. Cultural Landscapes and Environmental Change; Arnold: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shimrah, T.; Bharali, S.; Rao, K.; Saxena, K.G. Cultural Landscapes: The Basis for Linking Biodiversity Conservation with the Sustainable Development in West Kameng, Arunachal Pradesh. In Cultural Landscapes: The Basis for Linking Biodiversity Conservation with the Sustainable Development; Ramakrishnan, P., Saxena, G., Rao, K., Sharma, G., Eds.; UNESCO: New Delhi, India, 2012; pp. 105–148. [Google Scholar]

- Koning, J. Social Sustainability in a Globalizing World. In More on Most: Proceedings of an Expert Meeting; Van Rinsum, H., de Ruijter, A., Eds.; National UNESCO Commission: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bigon, L.; Bitton, Y.; Langenthal, E. “Place Making” and “Place Attachment” as Key Concepts in Understanding and Confronting Contemporary Urban Evictions: The Case of Givat-Amal, Tel Aviv. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2022, 57, 1577–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, D.; Demiröz, M.; Szemző, H.; De Luca, C. Adapting Methods and Tools for Participatory Heritage-based Tourism Planning to Embrace the Four Pillars of Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J. Introduction: Introducing Philosophy of the City. Topoi 2021, 40, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigon, L. African History and Global Urban History: A Comment. The Global Urban History Blog. 2016. Available online: https://globalurbanhistory.com/2016/07/07/african-urban-history-and-global-history-a-comment/ (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Bigon, L.; Langenthal, E. How Sustainable is our Urban Social-Sustainability Theory. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R.; Burgess, E. The City; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, L. The Culture of Cities; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: Orlando, FL, USA, 1970. first published in 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Esbjörn-Hargens, S.; Zimmerman, M. Integral Ecology: Uniting Multiple Perspectives on the Natural World; Shambhala Publications: Boston, MA, USA; Integral Books: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. The Significance of Storage in Hunting Societies. Man 1983, 18, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostof, S. The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings through History; Little, Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Y. Nimrod the Mighty, King of Kish, King of Sumer and Akkad. Vetus Testam. 2002, 52, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovich, D. Identifying Nimrod of Genesis 10 with Sargon of Akkad by Exegetical and Archaeological Means. J. Evang. Theol. Soc. JETS 2013, 56, 273–305. [Google Scholar]

- Abramski, S. Nimrod and the Land of Nimrod. Beth Mikra 1980, 82, 237–255. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Van der Toorn, K.; Van der Horst, P.W. Nimrod Before and After the Bible. Harv. Theol. Rev. 1990, 83, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, J.A.; Fadamiro, J. Urbanisation Forces on the Landscapes and the Changing value-systems of Osun Sacred Grove UNESCO Site, Osogbo, Nigeria. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 798–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Population, Total-Nigeria. 2022. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?end=2020&locations=NG (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Krapf-Askari, E. Yoruba Towns and Cities; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Adelusi-Adeluyi, A.; Bigon, L. City Planning: Yorùbá City Planning. In Encyclopedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundiran, A. The Yoruba: A New History; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, Indiana, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bascom, W. Urbanization among the Yoruba. Am. J. Sociol. 1955, 60, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, O. Lagos Past; No indicated Publisher: Lagos, Nigeria, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Ojo, A. Royal Palaces: An Index of Yoruba Traditional Culture. Niger. Mag. 1967, 10, 194–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ojewuyi, O. Wole Soyinka: The Hunter, The Hunt. Theater 1997, 28, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okediran, W. Soyinka in Ebedi: Of Hunters and Storytellers. Nigerian Tribune. 23 February 2022. Available online: https://tribuneonlineng.com/soyinka-in-ebedi-of-hunters-and-storytellers/ (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Macrotrends: The Premier Research Platform for Long Term Investors. City Populations of Osogbo, Ibadan, Lagos (Nigeria). 2024. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/cities/22014/oshogbo/population (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Adedeji, J.A. Ecological Urbanism of Yoruba Cities in Nigeria: An Ecosystem Services Approach; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Adedeji, J.A. Yoruba Architectural Sites in Nigeria. Springs Rachel Carson Cent. Rev. 2023, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove, Nigeria. 2014 World Monuments Watch, World Monuments Fund (New York). Available online: https://www.wmf.org/project/osun-osogbo-sacred-grove (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Daley, B. Nigeria’s Sacred Osun River Supports Millions of People—But Pollution is Making it Unsafe. The Conversation. 27 September 2022. Available online: https://theconversation.com/nigerias-sacred-osun-river-supports-millions-of-people-but-pollution-is-making-it-unsafe-191152 (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Watson, R. Ibadan—A Model of Historical Facts: Militarism and Civic Culture in a Yoruba City. Urban Hist. 1999, 26, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, N. Political Landscapes. In The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Cultural Geography; Johnson, N., Schein, R., Winders, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunlami, A. Cheapest Nigerian Cities to Live In. Travelstartblog. 11 July 2014. Available online: https://www.travelstart.com.ng/blog/10-cheapest-nigerian-cities-live/ (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Adejumo, S.A.; Osunwale, S. Urban Expansion and Loss of Watershed of Eleyele Dam in Ibadan, Nigeria. CSID J. Infrastruct. Dev. 2024, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, A.S. Residents’ Perception of Household Wellbeing on Upland Trees Conservation in Mitigating Flood in Selected Flood-Prone Communities of Oyo State, Nigeria. IRASD J. Energy Environ. 2024, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losi, J. History of Lagos; African Education Press: Lagos, Nigeria, 1967. first published in 1914. [Google Scholar]

- Bigon, L. The Former Names of Lagos (Nigeria) in Historical Perspective. Names 2011, 59, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]