Charting a Path to Sustainable Workforce: Exploring Influential Factors behind Employee Turnover Intentions in the Energy Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Human Resource Management

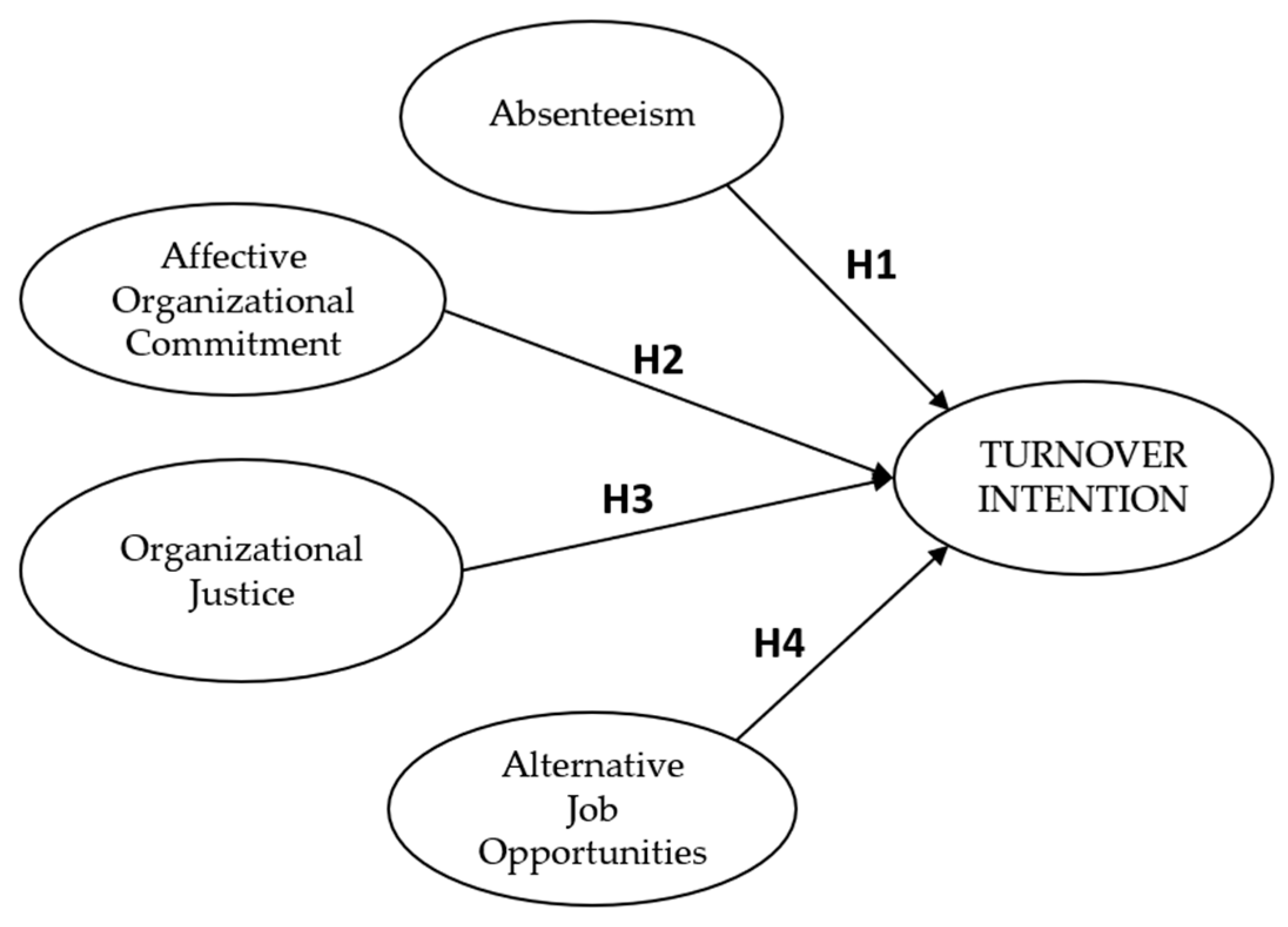

2.2. Turnover Intention

2.3. Absenteeism

2.4. Affective Organizational Commitment

2.5. Organizational Justice

2.6. Alternative Job Opportunities

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Measuring Scales

3.2. Missing Data and Outliers

3.3. Sample Description

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

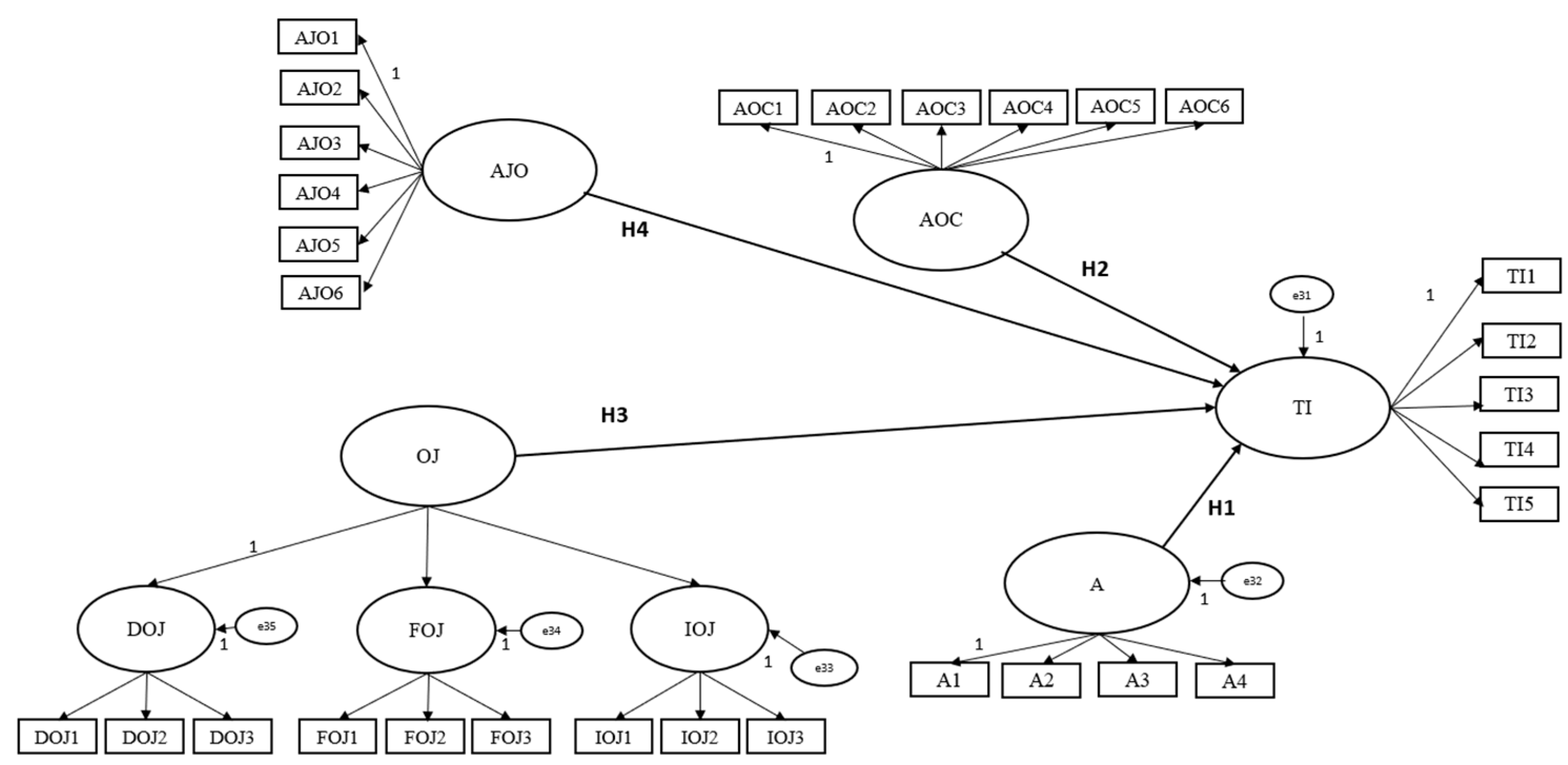

4.2. Higher-Order Latent Variables

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.4. Structural Model Testing

).

).5. Discussion and Conclusions

- Shift the focus from primarily material resources to human resources;

- Strengthen affective commitment to build normative and continuance commitment that collectively create loyal employees;

- Pay attention to increased absenteeism rates so that they can be managed both proactively and reactively;

- Due to the sensitivity of the human ego, which constantly compares itself with others (inside and outside the organization—this can also influence the perception of alternatives), ensure justice: eliminate differences in material compensation between women and men; perceive, praise and reward results; treat employees kindly and continuously inform them about decisions that affect their work;

- Try to identify the reasons why employees leave after they have left.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bryant, P.C.; Allen, D.G. Compensation, Benefits and Employee Turnover. Compens. Benefits Rev. 2013, 45, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrium; Lowrey, C. The Cost of Employee Turnover. 2017. Available online: https://www.atriumstaff.com/cost-employee-turnover/ (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Hom, P.W.; Lee, T.W.; Shaw, J.D.; Hausknecht, J.P. One hundred years of employee turnover theory and research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkowska, A.; Tokarz-Kocik, A.; Drela, K.; Bera, A. Employee Financial Wellness Programs (EFWPs) as an Innovation in Incentive Systems of Energy Sector Enterprises in Poland during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Current Status and Development Prospects. Energies 2022, 15, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirayath, S.; Bhandari, D. Does emotional intelligence really impact employee job satisfaction? An experience from resources and energy sector in Bhutan. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2022, 26, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kronos. Available online: https://www.kronos.co.uk/products/workforce-central-suite/workforce-absence-manager (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Absence Insight. Available online: https://absenceinsight.eu/ (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Shah, I.A.; Csordas, T.; Akram, U.; Yadav, A.; Rasool, H. Multifaceted Role of Job Embeddedness Within Organizations: Development of Sustainable Approach to Reducing Turnover Intention. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sypniewska, B.; Baran, M.; Kłos, M. Work engagement and employee satisfaction in the practice of sustainable human resource management—Based on the study of Polish employees. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 19, 1069–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obum, O.E.; Kelana, B.W.Y.; Rahim, N.S.A.; Saidi, M.I.; Hishan, S.S. Testing Effects of Job Satisfaction and OCBs on the Relationship between Talent Management and Talented Employee Turnover for Sustainable Human Resource Development in Healthcare. Migr. Lett. 2023, 20, 648–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachon-Rodríguez, G.; Blanco-Gonzalez, A.; Prado-Román, C.; Del-Castillo-Feito, C. How sustainable human resources management helps in the evaluation and planning of employee loyalty and retention: Can social capital make a difference? Eval. Program Plan. 2022, 95, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, D.R.; Ribeiro, N.; Santos, M.J. “Searching for Gold” with Sustainable Human Resources Management and Internal Communication: Evaluating the Mediating Role of Employer Attractiveness for Explaining Turnover Intention and Performance. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, L.J. When case studies are not enough: The influence of corporate culture and employee attitudes on the success of cleaner production initiatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2000, 8, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opatha, H.D.N.P. Sustainable Human Resource Management; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: Beau Bassin, Mauritius, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Holtom, B.C.; Mitchell, T.R.; Lee, T.W.; Eberly, M.B. 5 turnover and retention research: A glance at the past, a closer review of the present, and a venture into the future. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2008, 2, 231–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer, S.F.; Blanchard, C.; Vallerand, R.J. A Motivational Model of Work Turnover. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 2089–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.G.; Hogan, N.L.; Barton, S.M. The Impact of Job Satisfaction on Turnover Intent: A Test of a Structural Measurement Model Using a National Sample of Workers. Soc. Sci. J. 2001, 38, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ployhart, R.E.; Thomas, H.C.; Anderson, N.; Bliese, P.D. The power of momentum: A new model of dynamic relationship between job satisfaction change and turnover intentions. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B.; Petroni, A.; Dormio, A.I. Organizational socialization career aspirations and turnover intentions among design engineers. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2005, 26, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Bruvold, N.T. Creating value for employees: Investment in employee development. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2003, 14, 981–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothma, C.F.C.; Roodt, G. The validation of the turnover intention scale. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag./SA Tydskr. Vir Menslikehulpbronbestuur 2013, 11, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, J.K.; Griffeth, R.W.; Hom, P.W. A Comparison of Structural Models Representing Turnover Cognitions. J. Vocat. Behav. 1998, 53, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, P.W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Lee, T.W.; Griffeth, R.W. Reviewing Employee Turnover: Focusing on Proximal Withdrawal States and an Expanded Criterion. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 831–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harhara, A.S.; Singh, S.K.; Hussain, M. Correlates of employee turnover intentions in oil and gas industry in the UAE. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2015, 23, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntseke, T.; Mitonga-Monga, J.; Hoole, C. Transformational leadership influences on work engagement and turnover intention in an engineering organisation. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, B.; Che, X.; Sun, H.; Tan, M. Examining effect of green transformational leadership and environmental regulation through emission reduction policy on energy-intensive industry’s employee turnover intention in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayari, A.; AlHamaqi, A. Investigation of Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intention: A Study of Bahraini Oil and Gas Industry. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2022, 34, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gyabeng, E.; Sewu, G.J.A.; Nkrumah, N.K.; Dartey, B. Occupational health and safety and turnover intention in the Ghanaian power industry: The mediating effect of organizational commitment. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 3273045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, A.; Shaddady, A. Influences of Financial and Non-Financial Compensation on Employees’ Turnover Intention in the Energy Sector: The Case of Aramco IPO. Int. Bus. Res. 2021, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, W.; Ameen, A.; Isaac, O.; Khalifa, G.S.; Shibami, A.H. The mediating effect of job happiness on the relationship between job satisfaction and employee performance and turnover intentions: A case study on the oil and gas industry in the United Arab Emirates. J. Bus. Retail Manag. Res. 2019, 13, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnan, L.; Awan, F.H.; Abrar, U.; Saleem, A.; Yang, J.; Ali, S. Newly Constructed Power Plants in Pakistan along-with HR Practices. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET), Sukkur, Pakistan, 29–30 January 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molopo, A.G.; Schultz, C.; Lessing, K.F. Prediction of turnover intention by demographic variables among engineers at a South African energy provider. J. Contemp. Manag. 2022, 19, 420–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Golan, R. Predicting absenteeism and turnover intentions by past absenteeism and work attitudes. Career Dev. Int. 2007, 12, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badubi, R.B. A Critical Risk Analysis of Absenteeism in the Work Place. J. Int. Bus. Res. Mark. 2017, 2, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchiella, F.; Gastaldi, M.; Ranieri, L. Managing absenteeism in the workplace: The case of an Italian multiutility company. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oenning, N.S.X.; Carvalho, F.M.; Lima, V.M.C. Risk factors for absenteeism due to sick leave in the petroleum industry. Rev. De Saude Publica 2014, 48, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Fuentes, A.; Busto Serrano, N.M.; Sánchez Lasheras, F.; Fidalgo Valverde, G.; Suárez Sánchez, A. Prediction of health-related leave days among workers in the energy sector by means of genetic algorithms. Energies 2020, 13, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wormuth, B.; Wang, S.; Dehghanian, P.; Barati, M.; Estebsari, A.; Filomena, T.P.; Kapourchali, M.H.; Lejeune, M.A. Electric power grids under high-absenteeism pandemics: History, context, response, and opportunities. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 215727–215747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łakomiak, A. The Condition of the Polish Energy Sector in a Post-Pandemic Environment. Accounting and Business in a Sustainable Post-COVID World: New Perspectives and Challenges; Uniwersytet ekonomiczny we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2022; pp. 164–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, G. Size of Industrial Organization and Worker Behavior; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, N.; Arnold, J.; Gelade, G.; The Effects of Transformational Leadership on Employees’ Absenteeism in Four UK Public Sector Organisations. Health and Safety Laboratory for the Health and Safety Executive 2009. 2009. Available online: http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr648.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Johns, G. The Psychology of Lateness, Absenteeism, and Turnover. In Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology; Volume 2: Organizational, Psychology; Anderson, N., Ones, D.S., Sinangil, H.K., Viswesvaran, C., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, S.A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Rutte, C.G. Absenteeism, turnover intention and inequity in the employment relationship. Work Stress 1999, 13, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R.T. The Role of Performance and Absenteeism in the Prediction of Turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trice, H.M.; Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Employee-Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover. Contemp. Sociol. 1984, 13, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.E. Predicting absenteeism and turnover: A field comparison of Fishbein’s model and traditional job attitude measures. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, T.F. Turnover and absenteeism: A review of relationships and shared correlates. Pers. Psychol. 1972, 25, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsberger, H.A.; Herzberg, F.; Mausner, B.; Peterson, R.O.; Capwell, D.F. Job Attitudes: Review of Research and Opinion. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1959, 12, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, R.M.; Rhodes, S.R. Major influences on employee attendance: A process model. J. Appl. Psychol. 1978, 63, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W.H.; Griffeth, R.W.; Hand, H.H.; Meglino, B.M. Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 493–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.A.; Newman, D.A.; Roth, P.L. How important are job attitudes? Meta-analytic comparisons of integrative behavioral outcomes and time sequences. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, J.; Gharakhani, D. Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction. ARPN J. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, I.M. Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and Turnover Intention of Online Teachers in the K-12 Setting. Ph.D. Thesis, Bagwell College of Education, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA, USA, 2015. Available online: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=instruceddoc_etd (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Lambert, E.G.; Griffin, M.L.; Hogan, N.L.; Kelley, T. The Ties That Bind: Organizational Commitment and Its Effect on Correctional Orientation, Absenteeism, and Turnover Intent. Prison J. 2014, 95, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 1405–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einolander, J. Organizational commitment and engagement in two finnish energy sector organizations. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2016, 26, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzeller, C.O.; Celiker, N. Examining the relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention via a meta-analysis. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 14, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkathiri, A.S.; Abuelhassan, A.E.; Khalifa, G.S.A.; Nusari, M.; Ameen, A. The Impact of Perceived Supervisor Support on Employees Turnover Intention: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and Affective Organizational Commitment. Int. Bus. Manag. 2018, 12, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Kandampully, J. Reducing Employee Turnover Intention Through Servant Leadership in the Restaurant Context: A Mediation Study of Affective Organizational Commitment. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2017, 19, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S.A. Organizational commitment, turnover intentions and the influence of cultural values. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 76, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, T.; Lei, S.; Haider, M.J.; Hussain, S.T. The impact of organizational justice on employee innovative work behavior: Mediating role of knowledge sharing. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A. Essentials of Organizational Behavior, 14th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A. Organiazcijsko Ponašanje, 12th ed.; Paerson, Prentice Hall, Mate: Zagreb, Croatia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yasar, M.F.; Emhan, A.; Ebere, P. Analysis of organizational justice, supervisor support, and organizational commitment: A case study of energy sector in Nigeria. J. Bus. Stud. Q. 2014, 5, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A. On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palaiologos, A.; Papazekos, P.; Panayotopoulou, L. Organizational justice and employee satisfaction in performance appraisal. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2011, 35, 826–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, E.M.D.; Bakker, A.B.; Syroit, J.E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Unfairness at work as a predictor of absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.S.; Pangil, F. The Effect of Fairness of Performance Appraisal and Career Growth on Turnover Intention. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2016, 10, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowski, J.M.; Conlon, D.E. Organizational justice: Looking back, looking forward. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2005, 16, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Davis-Blake, D. Salary dispersion, location in the salary distribution, and turnover among college administrators. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1992, 45, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.L.; Mueller, C.W. A causal model of turnover for nurses. Acad. Manag. J. 1981, 24, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, A.; Amjad, M.S.; Bilal, B.; Saeed, M.M. The Moderating Effect of Perceived Alternative Job Opportunities between Organizational Justice and Job Satisfaction: Evidence from Developing Countries. East Asian J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 4, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J.A.; Viano, S.L.; Selin, J.L. Understanding Employee Turnover in the Public Sector: Insights from Research on Teacher Mobility. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavey, A.L.; Holwerda, J.A.; Hausknecht, J.P. Causes and consequences of collective turnover: A meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 412–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Sablynski, C.J.; Burton, J.P.; Holtom, B.C. The Effects of Job Embeddedness on Organizational Citizenship, Job Performance, Volitional Absences, and Voluntary Turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, R.P. Turnover theory at the empirical interface: Problems of fit and function. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridakis, G.; Cooper, C. Research Handbook on Employee Turnover; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pepra-Mensah, J.; Adjei, N.L.; Yeboah-Appiagyei, K. The Effect of Work Attitudes on Turnover Intentions in the Hotel Industry: The Case of Cape Coast and Elmina (Ghana). Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 7, 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Dardar, A.H.A.; Jusoh, A.; Rasli, A. The Impact of Job Training, job satisfaction and Alternative Job Opportunities on Job Turnover in Libyan Oil Companies. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 40, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausknecht, J.P.; Trevor, C.O. Collective turnover at the group, unit, and organizational levels: Evidence, issues, and implications. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 352–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, R.; Steel, R.; Allen, D.; Bryan, N. The development of a multidimensional measure of job market cognitions: The employment opportunity index (EOI). J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwepker, C.H., Jr. Ethical climate’s relationship to job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention in the salesforce. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Liden, R.C. Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G.H. The relationships between job attitudes, personal characteristics, and job outcomes: A study of retail store managers. J. Retail. 1985, 61, 35–62. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, N.; Payne, R. Absence from Work: Explanations and Attributions. Appl. Psychol. 1987, 36, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Niehoff, B.P.; Moorman, R.H. Justice as Mediator of the Relationship between Methods of Monitoring and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 527–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, N.; Fern, C.T.; Budhwar, P. Explaining employee turnover in an Asian context. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2001, 11, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, J.L. The Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.Y.J.; Harwell, M.; Liou, S.M.; Ehman, L.H. Advances in missing data methods and implications for educational research. In Real Data Analysis; Sawilowsky, S.S., Ed.; Information Age Pub: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, J.L.; Graham, J.W. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Peng, C.-Y.J. Principled missing data methods for researchers. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, J.L. Multiple Imputation: A Primer. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1999, 8, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J.A.; Schenker, N. Missing Data. In Handbook of Statistical Modeling in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Arminger, G., Clogg, C.C., Sobel, M.E., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 39–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D.A. How can I deal with missing data in my study? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2001, 25, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Reliability analysis. In Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 2nd ed.; Field, A., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2005; Chapter 15. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A. Overall fit in covariance structure models: Two types of sample size effects. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Evaluating model fit. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziri, B. Job Satisfaction: A Literature Review. Manag. Res. Pract. 2011, 3, 77–86. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/article/rommrpase/v_3a3_3ay_3a2011_3ai_3a4_3ap_3a77-86.htm (accessed on 28 March 2023).

| % | ||

| Gender | Male | 64.7 |

| Female | 35.3 | |

| Age | 24–42 | 31.4 |

| 43–57 | 41.6 | |

| >58 | 25 | |

| Education | Primary school | 1.3 |

| High school | 58.1 | |

| Faculty | 38.7 | |

| Master’s degree and doctorate | 1.9 | |

| The level of your position in the organization | Operational employee | 90.4 |

| Middle management | 9.6 | |

| Top management | 0 | |

| Number of employees in the organization | <50 | 21.2 |

| 50–250 | 78.2 | |

| >250 | 0.6 | |

| Personal income level | <400 € | 40.4 |

| 401–800 € | 50.6 | |

| 801–1200 € | 8.3 | |

| 1201–1600 € | 0.6 | |

| Household income level | <400 € | 0.6 |

| 401–800 € | 11 | |

| 801–1200 € | 30.5 | |

| 1201–1600 € | 24.7 | |

| 1601–2000 € | 20.1 | |

| >2000 € | 13 |

| Variable | Item Abbr. | Item | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective Organizational Commitment | AOC1 | I feel emotionally attached to this organization. | 0.807 |

| AOC2 | I feel a “strong” sense of belonging to my organization. | 0.857 | |

| AOC3 | I do not feel like “part of the family” at my organization (reverse-coded). | 0.799 | |

| AOC4 | I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization. | 0.754 | |

| AOC5 | I really feel as if this organization’s problems are my own. | 0.761 | |

| AOC6 | This organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me. | 0.864 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient: 0.928 | |||

| Distributive Organizational Justice | DOJ1 | My work schedule is fair. | 0.511 |

| DOJ2 | I think that my level of pay is fair. | 0.552 | |

| DOJ3 | I consider my workload to be quite fair. | 0.904 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient: 0.779 | |||

| Formal Organizational Justice | FOJ1 | Job decisions are made by the superior in an unbiased manner. | 0.838 |

| FOJ2 | My superior makes sure that all employee concerns are heard before job decisions are made. | 0.866 | |

| FOJ3 | My superior collects accurate and complete information to make job decisions. | 0.873 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient: 0.921 | |||

| Interactional Organizational Justice | IOJ1 | When decisions are made about my job, my superior discusses the implications of the decisions with me. | 0.747 |

| IOJ2 | When decisions are made about my job, my superior offers adequate justification for decisions. | 0.892 | |

| IOJ3 | When decisions are made about my job, my superior offers explanations that make sense to me. | 0.844 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient: 0.944 | |||

| Alternative Job Opportunities | AJO1 | If I quit my current job, the chances that I would be able to find another job as good as, or better than my present one is high. | 0.909 |

| AJO2 | If I had to leave this job, I would have another job as good as this one within a month. | 0.902 | |

| AJO3 | There is no doubt in my mind that I can find a job that is at least as good as the one I now have. | 0.936 | |

| AJO4 | Given my age, education and general economic condition, the chance of attaining a suitable position in some other organization is slim (reverse-coded). | 0.920 | |

| AJO5 | The chance of finding another job that would be acceptable is high. | 0.982 | |

| AJO6 | It would be easy to find acceptable alternative employment. | 0.942 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient: 0.961 | |||

| Absenteeism | A1 | In the last 12 months, I was absent from my workplace. | 0.647 |

| A2 | In the last 12 months, I have been late to my workplace. | 0.817 | |

| A3 | In the last 12 months, I left my workplace early. | 0.649 | |

| A4 | In the last 12 months, I was absent from my workplace due to sick leave, even though my actual state of health allowed me to work undisturbed. | 0.710 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient: 0.792 | |||

| Turnover Intention | TI1 | I intend to leave my current organization within the next year. | 0.925 |

| TI2 | I intend to leave my current organization within the next two years. | 0.941 | |

| TI3 | I often think about leaving the organization I work for. | 0.666 | |

| TI4 | I am currently looking for another job. | 0.708 | |

| TI5 | I am seriously considering the possibility of resigning. | 0.778 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient: 0.916 | |||

| Constructs | Items | Standardized Loadings | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective Organizational Commitment | AOC1 | 0.734 | 0.927 | 0.680 | |

| AOC2 | 0.821 | ||||

| AOC3 | 0.824 | ||||

| AOC4 | 0.862 | ||||

| AOC5 | 0.846 | ||||

| AOC6 | 0.854 | ||||

| Alternative Job Opportunities | AJO1 | 0.894 | 0.964 | 0.818 | |

| AJO2 | 0.817 | ||||

| AJO3 | 0.918 | ||||

| AJO4 | 0.883 | ||||

| AJO5 | 0.951 | ||||

| AJO6 | 0.957 | ||||

| Absenteeism | A1 | 0.652 | 0.802 | 0.505 | |

| A2 | 0.801 | ||||

| A3 | 0.648 | ||||

| A4 | 0.730 | ||||

| Turnover Intention | TI1 | 0.806 | 0.916 | 0.685 | |

| TI2 | 0.786 | ||||

| TI3 | 0.809 | ||||

| TI4 | 0.834 | ||||

| TI5 | 0.898 | ||||

| Organizational Justice CR = 0.931 AVE = 0.819 | Distributive Organizational Justice | DOJ1 | 0.798 | 0.865 | 0.647 |

| DOJ2 | 0.715 | ||||

| DOJ3 | 0.891 | ||||

| Formal Organizational Justice | FOJ1 | 0.882 | 0.920 | 0.794 | |

| FOJ2 | 0.920 | ||||

| FOJ3 | 0.870 | ||||

| Interactional Organizational Justice | IOJ1 | 0.889 | 0.941 | 0.843 | |

| IOJ2 | 0.944 | ||||

| IOJ3 | 0.920 | ||||

| Goodness-of-fit (benchmarked values) | Fit statistics | ||||

| χ2/DF (1 to 3) | 1.775 | ||||

| CFI (0.90) | 0.929 | ||||

| IFI (>0.90) | 0.929 | ||||

| TLI (>0.90) | 0.920 | ||||

| SRMR (<0.08) | 0.062 | ||||

| RMSEA (<0.08) | 0.071 | ||||

| Constructs | Correlation | Correlation Squared ) | AVE1 ) | AVE2 ) | Discriminant Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOC<->OJ | 0.465 | 0.216 | 0.680 | 0.819 | Established |

| OJ<->A | −0.036 | 0.001 | 0.819 | 0.505 | Established |

| OJ<->TI | −0.349 | 0.122 | 0.819 | 0.685 | Established |

| OJ<->AJO | −0.007 | 0.000 | 0.819 | 0.818 | Established |

| AOC<->A | −0.065 | 0.004 | 0.680 | 0.505 | Established |

| AOC<->TI | −0.476 | 0.227 | 0.680 | 0.685 | Established |

| AOC<->AJO | −0.112 | 0.013 | 0.680 | 0.818 | Established |

| A<->TI | 0.097 | 0.009 | 0.505 | 0.685 | Established |

| A<->AJO | −0.050 | 0.003 | 0.505 | 0.818 | Established |

| TI<->AJO | 0.305 | 0.093 | 0.685 | 0.818 | Established |

| Relationship | Standardized Total Effects | p Value | Hypothesis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absenteeism |  | Turnover Intention | 0.098 | 0.301 | Not accepted |

| Affective Organizational Commitment |  | Turnover Intention | −0.317 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Organizational Justice |  | Turnover Intention | −0.127 | 0.042 | Accepted |

| Alternative Job Opportunities |  | Turnover Intention | 0.186 | 0.000 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Živković, A.; Pap Vorkapić, A.; Franjković, J. Charting a Path to Sustainable Workforce: Exploring Influential Factors behind Employee Turnover Intentions in the Energy Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198511

Živković A, Pap Vorkapić A, Franjković J. Charting a Path to Sustainable Workforce: Exploring Influential Factors behind Employee Turnover Intentions in the Energy Industry. Sustainability. 2024; 16(19):8511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198511

Chicago/Turabian StyleŽivković, Ana, Ana Pap Vorkapić, and Jelena Franjković. 2024. "Charting a Path to Sustainable Workforce: Exploring Influential Factors behind Employee Turnover Intentions in the Energy Industry" Sustainability 16, no. 19: 8511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198511