Abstract

Recreational running, both on roads and in mountains, is one of the most practiced physical activities worldwide, and so, the motivations behind participating have been quite extensively described in the literature. However, the cultural and environmental motivations behind these athletes traveling to other countries or destinations to compete have not been properly addressed yet. The aim of this research is to analyze the motivations of sport tourists and to compare the motivations that cause mountain runners and city runners to compete. A cross-sectional study with a total of 244 athletes, divided into a group of city marathon runners (N = 118) and a group of mountain ultra-marathon runners (N = 126), was conducted. Athletes completed the Sports Tourism Motivation Scale (STMS), composed of 37 items and nine dimensions, through an online survey. Participants were asked questions related to their age, running experience, distance to events, numbers of nights in hotels and volunteering. The results showed that there were statistically significant differences in four out of the nine dimensions of the STMS between city and mountain runners’ motivations and, likewise, statistical differences were found in some dimensions of the scale related to participants’ sex, age, running experience, numbers of nights in a hotel, travel distance and volunteering. In conclusion, the reasons why runners participate in mountain and city running events are different; likewise, some sociodemographic variables should be taken into account when organizing such sporting events in a sustainable way, in order to provide organizers with the most suitable information and attract the most participants.

1. Introduction

Sport and physical activities are considered global or worldwide activities [1], and so, traveling to another country to practice sports is becoming more common [2]. The reasons why people travel for sporting events can be to participate either actively, taking part as an athlete in different sporting events, or passively, as a spectator [3]. More and more sports tourists are organizing their holidays in relation to popular sports events [4]. Moreover, since the growth in opportunities for amateur athletes, active sport tourists can be divided into two types, non-event participants (e.g., golf, skiing, surfing) and event participants [5]. In this way, within the different sports and physical activity options, participation in running has increased significantly in recent years [6]. This increase in participation could be explained to some extent by the characteristics of recreational running, since it is a low-cost option and does not come with many extra expenses [7], even though another motivational reasons can be determinants when practicing this sport. In order to better comprehend athletes’ motivations to run, and due to their importance related to sustainable leisure, many investigations have been carried out in the literature, and athletes’ motivations have been quite extensively analyzed, since these motivations help to explain athletes’ participation in different sporting events [8]. When it comes to recreational running or jogging, most of the investigations used the motivation of marathoner scale, or MOMS [9], trying to understand athletes’ motivations to run in different populations like adults or the general population [10], older adults [11], night runners [NO_PRINTED_FORM] and youth athletes. Within these investigations, such variables like the years of running experience [12], running distances, marital status, age and gender have been analyzed to understand athletes’ motivations to run [10]. Moreover, the MOMS has been used in different countries like the United States [9], Chile [13], Belgium [14], Poland [15], Spain [16] and Greece [17]. However, in these previous investigations, athletes’ cultural, nature or environmental motivations were not considered, since the MOMS analyzes athletes’ physical, social, achievement and psychological motives, but not their tourism- and environmental-related motivations [18], with these variables being unclear. Understanding travel-related motivations is important for the sustainable management of sporting events in cultural cities and natural landscapes.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

Due to the complexity of travel motivation, hitherto different approaches have been used to measure the travel motivations of participants in different sports activities like skiing and snowboarding [19], mountain sports [20], cycling [21] or surfing [22]. However, they were conducted using different theoretical constructs, some of them being to some extent limited. Other than that, for example, the tourism potential of small-scale sports events has been also analyzed [5,23]. More recently, Hungenberg et al. [24], with a sample of athletes, developed the Sport Tourism Motivation Scale (STMS), which was created to better comprehend active sport tourists’ motivations and their social and psychological motivations to travel. With this scale, some limitations of sport tourism motivation scales and running motivation scales like the MOMS were somewhat covered. These authors created a motivation scale gathering active sport-related motivations (self-enrichment, skill mastery, social needs, aggression, competitive desire, physical fitness) and tourism-related motivations, in which push and pull travel motivations were described [25]: two push factors (stress relief and travel exploration) and one pull factor (destination attributes). The motivation of active sports tourists was recently analyzed by Mishra et al. [18]. They used an adapted version of the STMS to better understand active sports tourist participants’ motivation, and through a cross-national attempt, analyzed a sample of Polish participants and compared them with a sample of Indian active sport tourists’ motivations.

Environmental aspects, due to the importance and influence that they might have on a participant, have also been considered in relation to athletes’ participation. This way, for example, travel motives can be closely related to the nature-related characteristics of the destination, creating nature-based tourism [26]. Deelen et al. [27] analyzed runners’ motives and attitudes related to environmental characteristics and concluded that perceived environmental characteristics were important determinants of the attractiveness of novice and experienced athletes. Within active sport tourism, contextual aspects like travel destination need to be taken into consideration; sports tourists might prioritize the destination over the actual activity, i.e., active sport tourists might change their intention to participate in an sport event depending on the travel destination [28]. In addition, it is not only contextual aspects that influence active sport tourists to travel, since personal variables like the athlete’s age seem to have an influence on these travel motivations. In this way, IJspeert and Hernandez-Maskivker [29] found significant differences among millennials and baby boomers regarding their needs and motivations to travel. Likewise, and due to the importance attributed to it, athletes’ running experience or years of running has been previously analyzed with regard to athletes’ motives to run [11,27], even though the obtained results have been somewhat inconsistent.

In order to better comprehend athletes’ motivations to run, many investigations have been carried out in the literature; however, runners’ tourism-related motivation and cultural or environmental aspects have not been properly addressed yet. In addition, the fact that the sample was composed of runners, i.e., a specific group of active sports tourists, is an added value not described in the literature using the STMS, as well as the fact that the different demographic characteristics of the respondents were considered [18]. Therefore, the aim of this research was to analyze the motivation of runner tourists in relation to running environment, thus comparing the motivations of mountain runners and city runners to travel and compete, according to their sex, age, running experience, distance to the event, nights in a hotel and volunteering.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design and Participants

The design of this study was descriptive, quantitative and cross-sectional and examined 244 amateur athletes participating in a city marathon (N = 118) and in a mountain ultra-marathon (N = 126) race. The sample was stratified by gender, age, running experience, distance to the event and volunteering.

3.2. Measures

Following previous investigations related to runners’ motivations [11,15], participants were asked about some sociodemographic variables such as gender (male, female) and age (18–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–68). Moreover, years of running experience (<1, 1–2, 3–4, >5 years), distance to the event (25–50 km, >50 km), number of nights in a hotel (0, 1–2, 3–4, >5 night) and volunteering (in a city marathon, in a mountain ultra-marathon).

An adapted version of the Sport Tourism Motivation Scale (STMS), in which items derived from previously validated questionnaires were used, was used to collect the information related to participants’ motivations [24]. The STMS consists of nine dimensions: self-enrichment (personal-related motivations), travel exploration (travel effect-related motivations), skill mastery (performance-related motivations), social needs (people relationship-related motivations), destination attributes (landscape-related motivations), stress relief (psychology-related motivations), aggression (related to fun and bringing out sports’ aggressive aspects), competition (competition-related motivations) and physical fitness (health-related motivations). These dimensions were divided into two groups, sport-related motivations (self-enrichment, skill mastery, social needs, destination attributes, aggression, competition and physical fitness) and tourism-related motivations, in which both push and pull factors were described [25]: two push factors (travel exploration, stress relief) and one pull factor (destination attributes). The questionnaire included 37 items with a 7-point Likert scale, with 7 being the highest score or most important motive for participating (7 = most important reason) and 1 being the lowest score or motive for participating (1 = not a reason). The questionnaire was prepared in Polish after being previously translated from the original English language and showing good reliability for use in the Polish language.

3.3. Procedure

City marathon and mountain ultra-trail runners were asked questions via an online platform, using Google Form technology [30]. Initially, they were asked about some sociodemographic questions, followed by the 37 items of the STMS. The questionnaire was sent to the organizers of Poznan Marathon (organized in the city of Poznan, full of monuments and cultural attractions) and Łemkowyna Ultra-Trail (organized in a national park with beautiful landscapes), who sent the survey to their runners a day after the race. To reduce the risk of bias related to completed questionnaires, preventive measures were implemented. These included, for example, monitoring the time participants spent completing the form, with responses completed in less than 5 min being rejected. Informed consent was clearly set at the beginning of the questionnaire, saying that all the participants were giving their consent, and participants were treated ethically, following the American Psychological Association ethics code [31]. The study took into account the principles set in the Helsinki declaration of 1975 and did not require formal ethical approval, because in accordance with the rules in force in Poland, the Bioethics Committee does not submit applications for surveys consisting in the use of standardized surveys used for their intended purpose, especially when the analysis involves statistically selected survey items [10,11]. The survey was anonymous, voluntary and confidential.

3.4. Data Analysis

A database was created with the collected information, and the statistical analysis was programmed with R Core Team. The analysis process involved an initial exploratory data analysis (EDA) followed by the group comparison analysis across the nine STMS dimensions—self-enrichment, travel exploration, skill mastery, social needs, destination attributes, stress relief, aggression, competition and physical fitness. The EDA included evaluating descriptive statistics and examining the correlations among variables In addition, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the correlation matrix to explore the associations and directions of the nine STMS dimensions. The group comparison involved two approaches: Welch’s t-test and one-way ANOVA. To ensure the validity of the analysis, Shapiro–Wilk tests were performed to assess the normality of the data. Given the large sample size, it was acknowledged that minor deviations from normality could affect the results. To address and enhance robustness, the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, a non-parametric alternative, was conducted as a parallel analysis to compare results under different sample size assumptions (large vs. small) simultaneously for group comparisons, hence providing cross-verification of the results and confirmation of their reliability regardless of normality assumptions.

Multiple post hoc comparisons with Tukey’s Honestly Significant Differences (HSD) test were conducted to identify which specific groups differed from each other. Additionally, eta squares (n2) were calculated to measure the effect size and determine how much the independent variables contributed to the dependent variable (i.e., STDM dimensions). Results were considered statistically significant at the p 0.05 level.

4. Results

Table 1 displays gender distributions across events and shows that females comprise 29% and males comprise 71% of the sample. The questionnaire was sent to the participants in a city-organized running event (2022 Poznan Marathon) and to runners on non-urban routes (2022 Łemkowyna Ultra-Trail).

Table 1.

Event participation across gender.

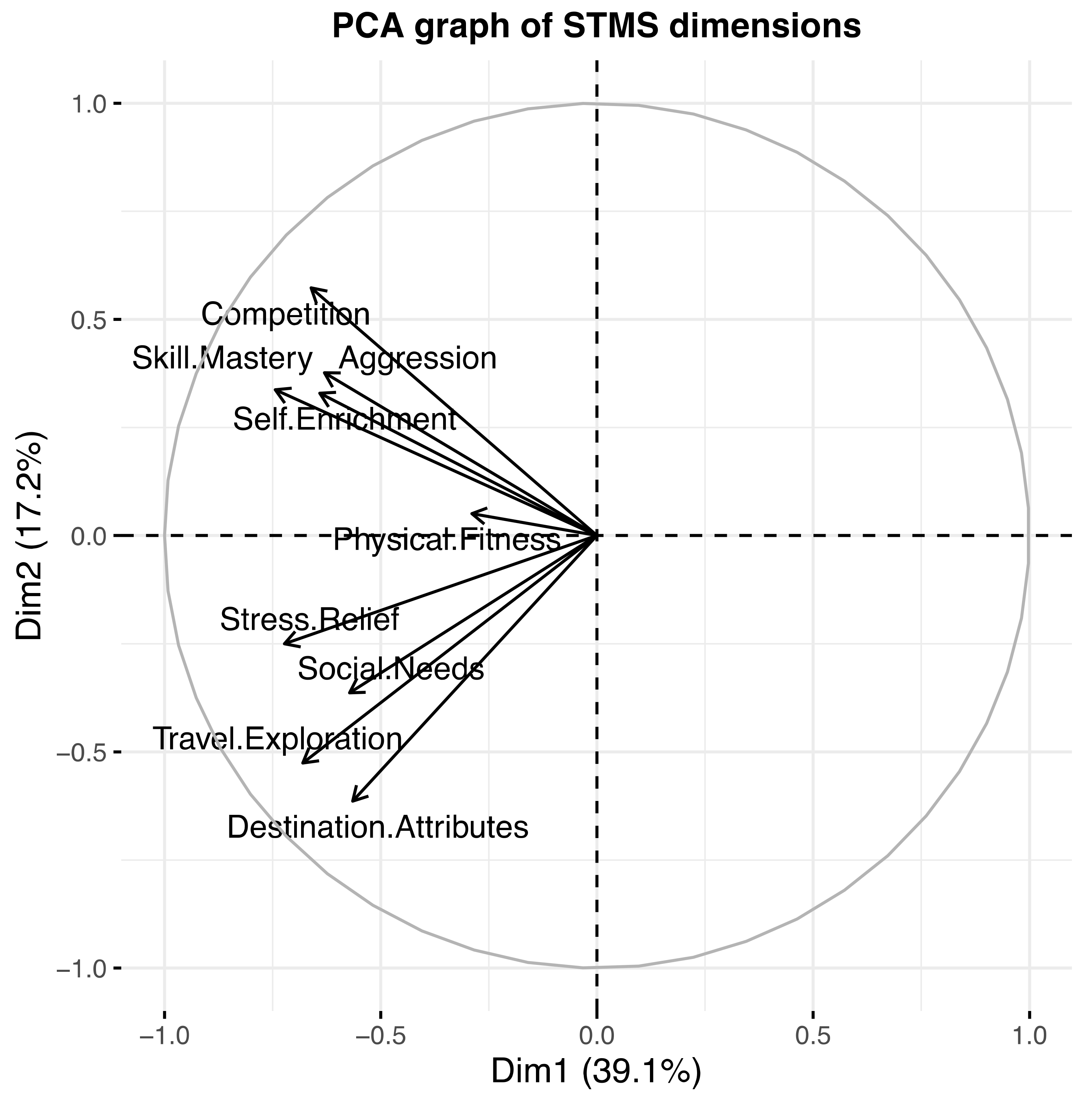

Figure 1 indicates that 56.3% of variance is captured by the first two principal components. This may indicate that more than two components may be recommended to measure the STMS dimension. The figure displays one group of dimensions composed of the competition, aggression, skill mastering, self-enrichment and physical fitness dimensions and a second group of dimensions with stress relief, social needs, travel exploration and destination attributes. The first group of dimensions seems to be oriented toward performance results, while the second group of dimensions seems to incline toward social and environment motives.

Figure 1.

Principal component analysis of the 9 STMS dimensions.

Table 2 shows the mean scores and standard deviation of the nine dimensions of the STMS, and some demographics and the correlation among these motivational dimensions. The three highest motivations to run for running travelers are connected to sports-related motivations of physical fitness (M = 5.68, SD ± 1.11), self-enrichment (M = 5.28, SD ± 1.08) and social needs (M = 5.12, SD ± 1.34), followed by travel exploration (M = 4.75, SD ± 1.39), while the motivations behind participating with the lowest scores are related to sports-related motives like aggression (M = 2.75, SD ± 1.58) and competition (M = 3.44, SD ± 1.62).

Table 2.

Mean scores, standard deviation and correlations of the 9 dimensions of the STMS dimensions and demographics.

Gender differences among running travelers show statistical differences in two dimensions of the STMS (Table 3): travel exploration (p < 0.01), and destination attributes (p < 0.01). In Table 3, we can see statistical differences in five out of nine dimensions of the STMS depending on the sport event landscape: self-enrichment, travel exploration (p < 0.05), skill mastery (p < 0.05), aggression (p < 0.05) and competition (p < 0.01).

Table 3.

Group differences. t-test comparison among STMS’s nine dimensions across gender and sport event.

In Table 4, we can see that the travel distance to the event shows statistical differences for two sports-related motives: aggression (p < 0.05) and competition (p < 0.01). In the case of volunteering, three out of nine dimensions show statistical differences, travel exploration (p < 0.05), social needs (p < 0.01) and destination attributes (p < 0.05), regarding the motivations of running travelers.

Table 4.

Group differences. t-test comparison among STMS’s nine dimensions across travel distance to the event and volunteering.

Table 5 shows statistical differences in four out of nine motivational dimensions of the STMS according to participants’ age groups: travel exploration, social needs, aggression and competition (p < 0.05). On the other hand, athletes’ running experience shows statistical differences in three motivation dimensions: self-enrichment, travel exploration and destination attributes (p < 0.05).

Table 5.

Group differences. One-way ANOVA comparison among STMS’s nine dimensions across age groups and running experience.

Table 6 shows that with regard to the number of hotel nights, tourism motivations like travel exploration and destination attributes (p < 0.05) show statistical differences; likewise, sport-related competition shows statistical differences (p < 0.05).

Table 6.

Group differences. One-way ANOVA comparison among STMS’s nine dimensions across hotel nights.

5. Discussion

The aim of this research is to describe the motivations of runner tourists in relation to the running environment, thus comparing the motivations of mountain runners and city runners to travel and compete, according to their sex, age, running experience, distance to the event, nights in a hotel and volunteering. The results showed that the highest scores were in physical fitness, self-enrichment and social needs, with these three being some of the sport-related motives, and followed by the three travel tourism dimensions of the STMS in this order: travel exploration, stress relief and running attributes.

Moreover, the results showed that runners’ tourists motivations differ according to the running scenario or sport event, with travel exploration being significantly higher for ultra-marathoners than for city runners, i.e., runners in nature significantly valued travel exploration. In addition, beyond travel motives, sport-related differences were found in self-enrichment, skill mastery, aggression and competition. These results are partially in line with the results obtained by Deelen [27] since they found that perceived environmental characteristics were important determinants of the attractiveness of the running environment, thus showing that the environmental aspects and nature matter when active sport travelers decide to move to a destination [26]. These are results that can be important, also, due to the connection of this leisure with a sustainable way of developing tourism [32]. When it comes to the runners’ gender, the results showed significant statistical differences between male and female runners with regard to travel exploration and destination attributes, with the rest of the sport-related motivations being non-significant. These results showed the importance of the travel dimensions for runner tourists, but at the same time, the sport-related motivations were not in line with previous investigations since motivation differences were found in different dimensions [10,15,17]. However, further research into the sport tourism motivation of runners would be needed in order to better compare these results. On the other hand, the results showed that age-related statistical differences were particularly sport related, so social needs, aggression and competition were statistically significant among different age groups, even though travel exploration was also shown to be different for the analyzed age groups. These results are partially in line with previous investigations related to runners’ motivation, since younger athletes were shown to be more motivated by competition and performance than older athletes [10,11,15].

As observed in the results, our results are not in line with a previous investigation that showed that the years of running experience did not differ among experienced and novice runners [12]. However, our results are partially in line with the results found related to running environments and athletes’ running experience [27] and with an investigation that analyzed older adult recreational runner motivations and running experience [11]. From these results, it seems that the running experience variable might be different depending on the sport and environmental running context; however, further research would be needed in order to obtain more accurate results. When it comes to the findings with regard to volunteering being athletes’ motivation, our results showed that travel exploration and destination attributes were statistically significant compared with non-volunteer athletes, with these both being travel motives. Moreover, social motives also were significantly higher for volunteers, thus showing that the profile of this type of participant is more closely related to travel than to the type of sport per se. Moreover, variables like travel distance to the event were only connected to sport-related motivations like competition and aggression. On the other hand, the number of nights in a hotel showed statistical differences in relation to two travel motivation dimensions like travel exploration and destination attributes, and also with competition, with the latter being a sport-related dimension. These results were partially in line with those of Johann and Mishra [28], who analyzed the participation of active sport tourism, concluding that active sport tourists might change their intention to participate in a sport event depending on the travel destination. It is important to take such variables into account in order to foster active sport tourism [33], which at the same time should be able to adapt to new generations’ characteristics and needs or motivations.

The study has some limitations, and these results need to be viewed carefully. For example, the sample is composed of 244 athletes, and even though they show an appropriate sample size, collecting a larger sample would provide further leverage for scale evaluation and validation and, thus, reinforce the results obtained. Moreover, the cross-sectional study design of this investigation was another limitation, since it did not allow for causal relationships to be established between the study variables. Other than that, the potential influence of cultural or regional factors on motivation could have been taken into account. However, despite these limitations, very few investigations about modern runners have analyzed active sports tourists’ motivation and their association with variables like the sport environment. Moreover, focusing only on runners can be understood as another strength of this study, since most research that analyzes the motivations of sports tourists do so by taking into account different sports within the same study. In future research, analyzing active sport tourism motivations across other types of sports events or taking into account different cultural contexts would help us to better understand active sport tourists’ motivations to travel.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, and based on the different dimensions of the STMS, it has been observed that runner tourists obtain the highest scores in physical fitness, self-enrichment and social needs, followed by the three travel tourism dimensions in this order: travel exploration, stress relief and running attributes. Moreover, this study shows that runners’ tourism motivations differ according to the running scenario or sport event, with travel exploration being higher for ultra-marathoners than for city runners. Likewise, volunteering, travel distance, gender, age, running experience and number of nights in a hotel showed statistical associations according to some dimensions of the STMS, so these characteristics should be taken into account when addressing different athlete travelers. Therefore, it would be interesting for event organizers and active sport tourist agencies to use this information in order to adapt and promote their events, so that participants are targeted more accurately. Knowledge about the motivations of active sports tourists is also important from the point of view of less popular tourist destinations. Attracting runners to new destinations may relieve the pressure on running destinations at risk of overtourism, especially in naturally valuable areas, thus regulating mass tourism and making these activities more sustainable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.-M. and P.L.-G.; methodology, M.R. and E.M.-M.; software, M.R. and E.G.; validation, M.R. and B.G.-O.; formal analysis, E.G.; investigation, A.W. and M.M.; resources, M.R., E.M.-M. and B.Ł.; data curation, E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, B.G.-O. and P.L.-G.; writing—review and editing, M.R., E.M.-M. and B.Ł.; visualization, B.Ł.; supervision, E.M.-M.; project administration, E.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study did not require formal ethical approval because, in accordance with the rules in force in Poland, the Bioethics Committee does not submit applications for surveys consisting in the use of standardized surveys, used in accordance with their intended purpose, when the research will develop statistically selected elements of the survey.

Informed Consent Statement

The questionnaire did not require the completion of a separate participant information sheet or consent form but clearly indicated that all questionnaire takers gave informed consent to the study. Respondents were informed about the course and character of the survey. The survey was voluntary and confidential.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to no access to the repository being publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hulteen, R.M.; Smith, J.J.; Morgan, P.J.; Barnett, L.M.; Hallal, P.C.; Colyvas, K.; Lubans, D.R. Global Participation in Sport and Leisure-Time Physical Activities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prev. Med. 2017, 95, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozalova, M.; Shchikanov, A.; Vernigor, A.; Bagdasarian, V. Sports Tourism. Pol. J. Sport Tour. 2014, 21, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.J. Active Sport Tourism: Who Participates? Leis. Stud. 1998, 17, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-García, M.; Ruiz-Chico, J.; Peña-Sánchez, A.R.; López-Sánchez, J.A. A Bibliometric Analysis of Sports Tourism and Sustainability (2002–2019). Sustainability 2020, 12, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Gibson, H.J. Predicting Behavioral Intentions of Active Event Sport Tourists: The Case of a Small-Scale Recurring Sports Event. J. Sport Tour. 2010, 15, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerder, J.; Breedveld, K.; Borgers, J. (Eds.) Running across Europe; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-349-49601-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlovskaia, M.; Vlahovich, N.; Rathbone, E.; Manzanero, S.; Keogh, J.; Hughes, D.C. A Profile of Health, Lifestyle and Training Habits of 4720 Australian Recreational Runners-The Case for Promoting Running for Health Benefits. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2019, 30, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Juan, F.; Zarauz Sancho, A. Análisis de La Motivación En Corredores de Maratón Españoles. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2014, 46, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, K.S.; Ogles, B.M.; Jolton, J.A. The Development of an Instrument to Measure Motivation for Marathon Running: The Motivations of Marathoners Scales (MOMS). Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1993, 64, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Guereño, P.; Tapia-Serrano, M.A.; Castañeda-Babarro, A.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E. Do Sex, Age, and Marital Status Influence the Motivations of Amateur Marathon Runners? The Poznan Marathon Case Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Guereño, P.; Galindo-Domínguez, H.; Balerdi-Eizmendi, E.; Rozmiarek, M.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E. Motivation behind Running among Older Adult Runners. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchrowicz-mośko, E.; Gravelle, F.; Dąbrowska, A.; León-guereño, P. Do Years of Running Experience Influence the Motivations of Amateur Marathon Athletes? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besomi, M.; Leppe, J.; Martínez, M.J.; Enríquez, M.I.; Mauri-Stecca, M.V.; Sizer, P.S. Running Motivations within Different Populations of Chilean Urban Runners. Eur. J. Physiother. 2017, 19, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stragier, J.; Vanden Abeele, M.; De Marez, L. Recreational Athletes’ Running Motivations as Predictors of Their Use of Online Fitness Community Features. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 37, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waśkiewicz, Z.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Gerasimuk, D.; Borysiuk, Z.; Rosemann, T.; Knechtle, B. What Motivates Successful Marathon Runners? The Role of Sex, Age, Education, and Training Experience in Polish Runners. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarauz, A.; Ruiz-Juan, F.; Flóres-Allende, G. Predictive Models of Motivation in Route Runners Based on Their Trainning Habits. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Ejerc. Deporte 2016, 11, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaidis, P.T.; Chalabaev, A.; Rosemann, T.; Knechtle, B. Motivation in the Athens Classic Marathon: The Role of Sex, Age, and Performance Level in Greek Recreational Marathon Runners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Malhotra, G.; Johann, M.; Tiwari, S.R. Motivations for Participation in Active Sports Tourism: A Cross-National Study. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2022, 13, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.D.; Gibson, H.J. The Attraction of Switzerland for College Skiers after 9/11: A Case Study. Tour. Rev. Int. 2004, 8, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, D.; Gibson, H. Benefits Sought and Realized by Active Mountain Sport Tourists in Epirus, Greece: Pre- and Post-Trip Analysis. J. Sport Tour. 2008, 13, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulks, P.; Ritchie, B.; Dodd, J. Bicycle Tourism as an Opportunity for Re-Creation and Restoration? Investigating the Motivations of Bike Ride Participants. In Proceedings of the New Zealand Tourism and Hospitality Research Conference, Hammer Springs, New Zealand, 3–5 December 2008; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Z.; Hritz, N.M. Surfing as Adventure Travel: Motivations and Lifestyles. J. Tour. Insights 2012, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Vogt, C. The Interrelationship between Sport Event and Destination Image and Sport Tourists’ Behaviours. J. Sport Tour. 2007, 12, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungenberg, E.; Gray, D.; Gould, J.; Stotlar, D. An Examination of Motives Underlying Active Sport Tourist Behavior: A Market Segmentation Approach. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 20, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipway, R.; Jones, I. Running Away from Home: Understanding Visitor Experiences and Behaviour at Sport Tourism Events. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 9, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M.; Normann, Ø. The Link between Travel Motives and Activities in Nature-based Tourism. Tour. Rev. 2013, 68, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deelen, I.; Janssen, M.; Vos, S.; Kamphuis, C.B.M.; Ettema, D. Attractive Running Environments for All? A Cross-Sectional Study on Physical Environmental Characteristics and Runners’ Motives and Attitudes, in Relation to the Experience of the Running Environment. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johann, M.; Mishra, S.; Malhotra, G.; Tiwari, S.R. Participation in Active Sport Tourism: Impact Assessment of Destination Involvement and Perceived Risk. J. Sport Tour. 2022, 26, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJspeert, R.; Hernandez-Maskivker, G. Active Sport Tourists: Millennials vs Baby Boomers. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2020, 6, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Šmigelskas, K.; Lukoševičiūtė, J.; Vaičiūnas, T.; Mozūraitytė, K.; Ivanavičiūtė, U.; Milevičiūtė, I.; Žemaitaitytė, M. Measurement of Health and Social Behaviors in Schoolchildren: Randomized Study Comparing Paper versus Electronic Mode. Slov. J. Public Health 2019, 58, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Poczta, J.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E. Modern Running Events in Sustainable Development—More than Just Taking Care of Health and Physical Condition (Poznan Half Marathon Case Study). Sustainability 2018, 10, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.J.; Lamont, M.; Kennelly, M.; Buning, R.J. Introduction to the Special Issue Active Sport Tourism. J. Sport Tour. 2018, 22, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).