Abstract

This study investigates the perceived ease of recycling in Glendale, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA, by household size, age, income, and gender. While existing research has broadly explored how sociodemographic factors impact recycling, there is a lack of comprehensive studies analyzing these factors within specific local contexts. This study aims to identify specific barriers and motivators across different demographics to enhance local recycling efforts using Glendale as a case study. Data were collected through an online survey of 111 respondents and analyzed using both quantitative and qualitative methods. The survey included questions about the demographic information, perceptions of recycling ease, and barriers to recycling. The analysis revealed that one-person households and young adults (18–35) face constraints such as limited space for recyclables, a lack of access to recycling bins in rental units, or high costs. Older adults (56 years or older) are highly committed but may face physical challenges. Higher-income households report higher participation due to better access and awareness, whereas lower-income households encounter significant barriers such as limited facility access and insufficient information. Gender differences indicate that women are slightly more proactive and committed to recycling compared to men. Recommendations include expanding recycling facilities, targeted educational campaigns, and economic incentives to encourage lower-income households, males, younger, and older adults. Addressing these demographic-specific barriers can improve recycling rates and contribute to more sustainable communities. Future studies should include in-person surveys as one of the limitations of this study is that an online survey format may introduce biases and the exclusion of residents without internet access.

1. Introduction

Recycling plays a role in the United Nations programs, especially under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework. In particular, SDG 12, which centers on consumption and production, aims to decrease waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse by 2030 [1]. This goal underscores the importance of sustainable waste management practices in reducing environmental impact and promoting sustainability worldwide.

Recycling is a critical component of sustainable waste management, offering significant environmental benefits such as reducing the need for raw materials, conserving energy, and minimizing landfill usage [2]. Effective recycling programs rely heavily on community participation, which is influenced by various sociodemographic factors, including household size, age, income, and gender [3].

Previous studies have highlighted various factors influencing recycling behaviors. For example, socioeconomic status, educational level, and access to recycling facilities significantly impact recycling rates [4,5]. The more educated a person is, the more likely they will engage in recycling [6]. Access to recycling facilities also plays a major role in whether a person recycles or not [7].

Larger households may generate more waste, which can lead to both increased recycling and challenges related to storage and sorting [8]. Similarly, Deshpande et al. (2024) highlighted that higher-income households tend to produce less waste, while lower-income households may rely on single-use products more often, resulting in increased waste generation [9]. Researchers in Sweden found that higher-income households tend to recycle more due to better access to recycling facilities and the ability to pay for associated costs [10]. On the other side of the economic spectrum, using a cross-sectional design that relied on 380 low-income households who live in coastal Peninsular Malaysia, a study found that lower-income households may face barriers such as a lack of access to recycling options, which can discourage participation, but they really wanted to recycle [11]. Doing a literature review of 80 documents, including published scientific articles, Schultz et al. (1995) found that higher income, but not gender or race, were predictors for recycling [12]. That being said, there is a research gap in analyzing how gender and age might affect recycling patterns.

Some research has shown that younger individuals are generally more environmentally conscious. For example, younger people may worry more about climate change and suffer from negative emotions or mental illnesses related to climate anxiety [13]. Other research suggests that women might also have negative thoughts about the future of the climate [14]. Gender differences in environmental behavior have also been documented. Torgler et al. (2009) and Barr et al. (2013) reported that women are generally more engaged in pro-environmental behaviors compared to men [15,16].

A 2012 study found that younger adults of college age, although reporting to care for the environment, were less likely than their parents to engage in certain environmentally friendly practices such as recycling, using reusable bags, eating less meat, and conserving water [17]. However, it also showed that younger adults were more likely to adopt greener transportation methods, including taking the train, the bus, riding a bike, or walking. This might indicate that what is considered sustainable could be different from generation to generation.

Despite the wealth of research on how sociodemographic factors affect recycling habits, there is still a need for studies that explore how household size, age, income, and gender collectively influence recycling behaviors within specific communities. Understanding these influences is vital for city planners and officials to develop targeted recycling initiatives that meet the varying needs of different demographic groups. The success of recycling programs relies heavily on community involvement and the convenience of recycling options for residents. Gaining insights into community attitudes and obstacles related to recycling is crucial for optimizing these initiatives.

Furthermore, public awareness campaigns have been shown to enhance recycling participation [12]. Studies have shown that eco-literacy efforts from the government can increase recycling rates among low-income households, for instance [11]. This is because specific barriers, such as confusion about recyclable materials and inadequate facilities, remain prevalent [18]. Creating a future involves developing customized approaches to meet the requirements and obstacles faced by various community sectors. By delving into the nuances of recycling habits, this study can guide the design of initiatives to boost recycling engagement among people from all walks of life. Enhancing recycling levels not only helps protect the environment by minimizing waste and preserving resources but also cultivates a mindset of sustainability within society.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background of Case Study

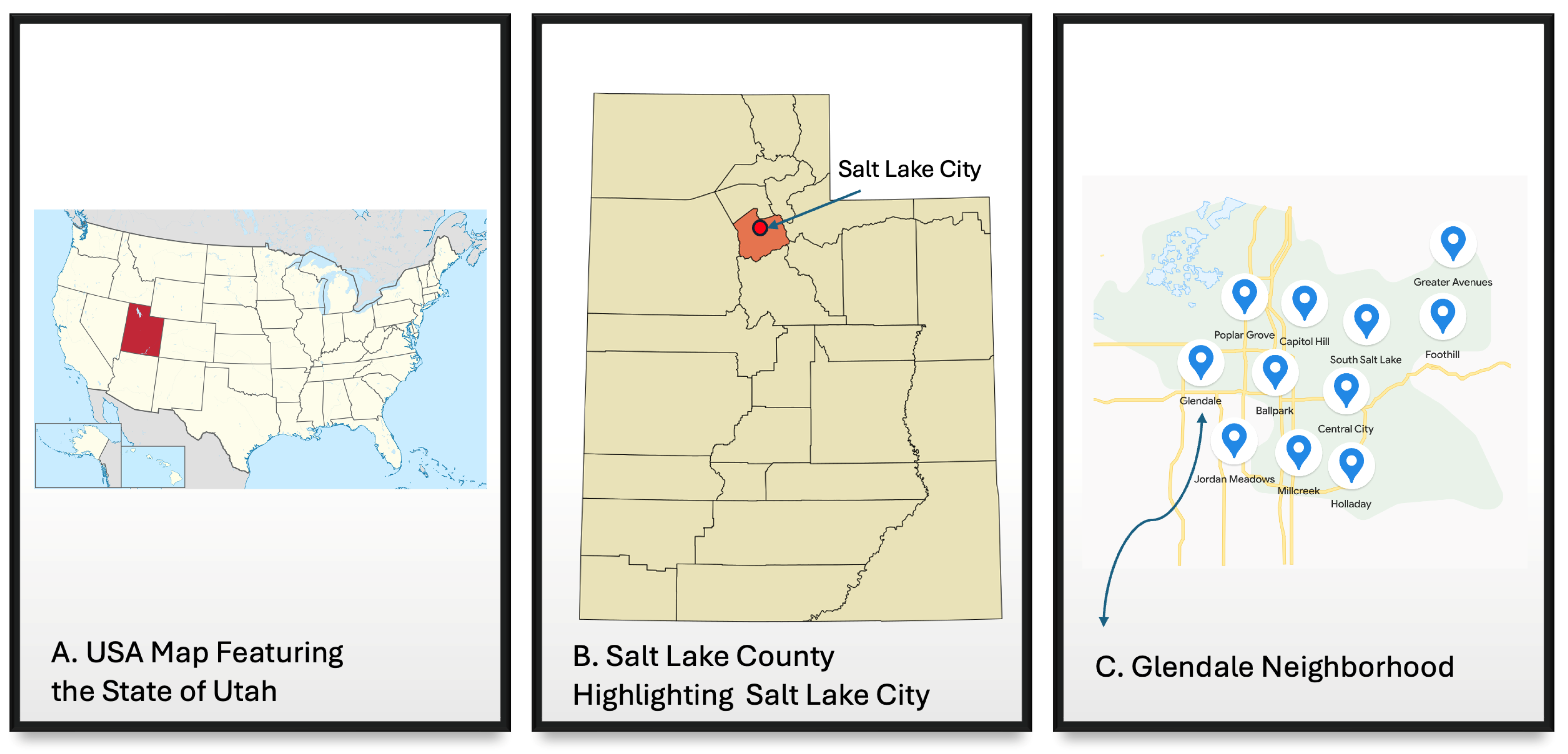

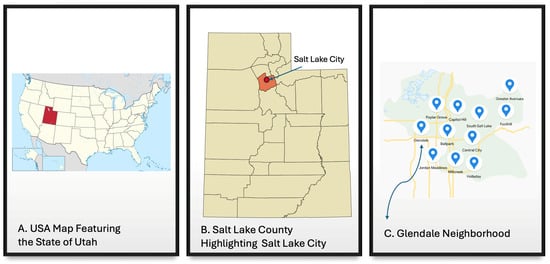

Figure 1 shows Glendale [D], a neighborhood located within Salt Lake City [C], Salt Lake City County [B], Utah [A], which was selected as a case study for this research due to the researcher’s relationship with the Glendale community council (a non-profit) and their need for a study on recycling for their application to Main Street America and the One Glendale Plan. While Glendale shares some demographic similarities with other U.S. urban areas, it stands out with a significantly younger population and a poverty rate more than three times higher than the national average. These differences highlight the unique socioeconomic challenges the community faces compared to the broader U.S. population.

Figure 1.

Map Locator. Sources: (A) [19], (B) [20], and (C) [21,22].

As shown in Table 1, according to the 2022 American Community Survey, the neighborhood was home to 11,614 people and 3048 households. Glendale features a mix of single-family homes, apartments, and rental units [23]. This mix makes it a prime spot for exploring how recycling practices differ based on household size, income levels, and age groups. The median household income in Glendale in 2022 was USD 61,380, the mean age was 29 years old, and about 41% of the residents rented their homes [23]. By focusing on Glendale, this study offers perspectives on how residents engage with recycling in an urban setting. It also allows for comparisons with neighborhoods across the country that have economic profiles. Table 1 focuses on key demographic and economic comparisons between Glendale, Salt Lake City, and the USA.

Table 1.

Glendale, Salt Lake City, and USA Key Demographics.

Homeowners in Glendale benefit from recycling services, usually covered in the city’s waste management charges, so residents do not have to pay extra for recycling. This setup makes curbside recycling an easily accessible choice for people. Moreover, Glendale offers drop-off spots across the city where residents can freely dispose of their items—especially glass, which is non-recycled by curbside pickup [24]. These drop-off locations are strategically positioned to assist those without service or those needing to recycle large amounts of materials. The city proactively shares details about these recycling choices.

2.2. Research Question and Ethics Approval

The research question that this study seeks to answer is: How do household size, age, income, and gender influence the perceived ease of recycling in Glendale, and what specific barriers and motivators affect the different demographic groups? The author collaborated with the Glendale community council to collect these data as part of their One Glendale Plan and their Main Street America application—where an organization must collect a variety of data for the designation. The inclusion criteria were to be over 18 years old and to be a Glendale resident. Participants knew this was conducted in collaboration with the University of Utah and had an approved Institutional Review Board (IRB) to conduct research on the west side and with community councils (protocol code 00119632, approved on 28 August 2018). Participation was voluntary, and measures were taken to ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of participants. The questions asked in the survey were the following:

- Recycling and Waste Management

- ○

- How easy/difficult is it to recycle in Glendale? (Select 1 to 5 from “somewhat easy” to “extremely difficult”)

- ○

- Can you think of any barriers to recycling in Glendale that the community council should address? If so, please explain. (Open-ended question)

- ○

- Are there any areas in Glendale where litter and/or waste are consistent problems? If so, where? (Open-ended question)

- Demographics

- ○

- What is your zip code?

- ○

- How many years have you lived in Glendale?

- ○

- What is your gender?

- ○

- What is your age?

- ○

- What is your race or ethnicity?

- ○

- Including yourself, how many people currently live in your household?

- ○

- What is your household annual income?

2.3. Data Collection, Analysis, and Limitations

The dataset collected responses from 111 Glendale residents about recycling and their demographics (e.g., multiple-choice, Likert scale, open-ended). As shown in Appendix A, an email was sent asking community members to fill out the survey using Survey Monkey and share it with others. In addition, Facebook and Instagram posts using the council page were also created. Several emails and social media post reminders were sent from 13 January to 1 March 2021 by the Community Council members and the University of Utah faculty and students involved in the project. The announcements and the surveys were available in English and Spanish. Moreover, several in-person reminders were conducted so that people could complete the survey online and share it with their neighbors.

The demographic questions that were collected included income, age, gender, and household size. The close-ended question related to recycling included: How easy/difficult is it to recycle in Glendale? The answers to these questions were on a Likert scale from “somewhat easy” to “extremely difficult”. The open-ended questions related to recycling included: Can you think of any barriers to recycling in Glendale that the community council should address? If so, please explain. Quantitative data were analyzed using statistical methods, including frequency distributions and cross-tabulations, to examine the relationship between the demographic variables and perceived ease of recycling. The qualitative analysis methods for open-ended responses used thematic analysis and coding procedures.

Before collecting data, this study did not conduct an analysis to determine how many responses were needed for statistical significance among different demographic groups. The goal was to gather a range of responses from the residents of Glendale, focusing on variations in household size, age, income, and gender. While a 95% confidence level with a ±5% margin of error is typically considered standard in social science research, these parameters were not explicitly defined in our initial study. However, 111 surveys for a population of 3048 means that our confidence level is 80% of the real value within ±6% of the measured/surveyed value. Future studies could improve the methodology by adopting an approach that includes determining sample sizes based on the desired confidence levels and margins of error to ensure statistical reliability. Our convenience sampling method may introduce selection bias, as it likely excludes residents who do not engage with these online communication platforms. About 13% of Glendale households do not have an internet connection [25]. This means that future studies should include in-person surveys.

Another limitation is that we generally asked about “recycling and waste management”, but we did not differentiate between household waste, electronic waste, light bulbs, renovation debris, etc. Most people in the U.S. would answer the survey related to everyday household waste. Future studies could ask more detailed questions on the types of waste.

Given that the data for this study were collected over three years ago, certain demographic and behavioral trends in Glendale may have shifted, particularly due to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent economic challenges. The pandemic likely influenced recycling habits due to changes in household composition, economic instability, and possible disruptions to city services. Future studies should incorporate updated data to understand these potential shifts better.

In this study, cross-tabulations were conducted to examine the relationships between demographic variables such as household size, income, age, and gender and their impact on the perceived ease of recycling in Glendale. Microsoft Excel was utilized for the analysis. After organizing the data properly, cross-references were made to generate contingency tables showing how demographic factors relate to recycling convenience levels, such as analyzing how various income brackets (like under USD 25k or USD 25k USD 49k) recycling ease and comparing household sizes (person or two-person households, etc.) with recycling habits. The analysis of these correlations revealed insights into the differences between groups, which are further discussed below.

3. Results

In this study, we found that households of one person face more significant barriers to recycling due to limited storage space and a perceived lack of impact, while larger households (two or more members) might have more established recycling routines. Young adults (18–35 years) encounter space constraints and busy schedules that hinder recycling efforts, middle-aged adults (36–55 years) seek more convenience in recycling facilities, and older adults (56 years or older) are committed but face physical challenges. Higher-income households exhibit higher recycling participation due to better access to facilities and greater awareness, whereas lower-income households face significant barriers such as limited facility access and insufficient information. Women are generally more proactive and committed to recycling, driven by environmental awareness and moral responsibility, while men are more influenced by convenience and economic incentives. Below are more details of the findings.

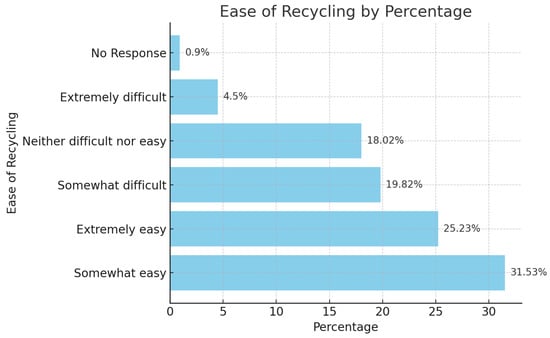

3.1. Easiness or Difficulty to Recycle

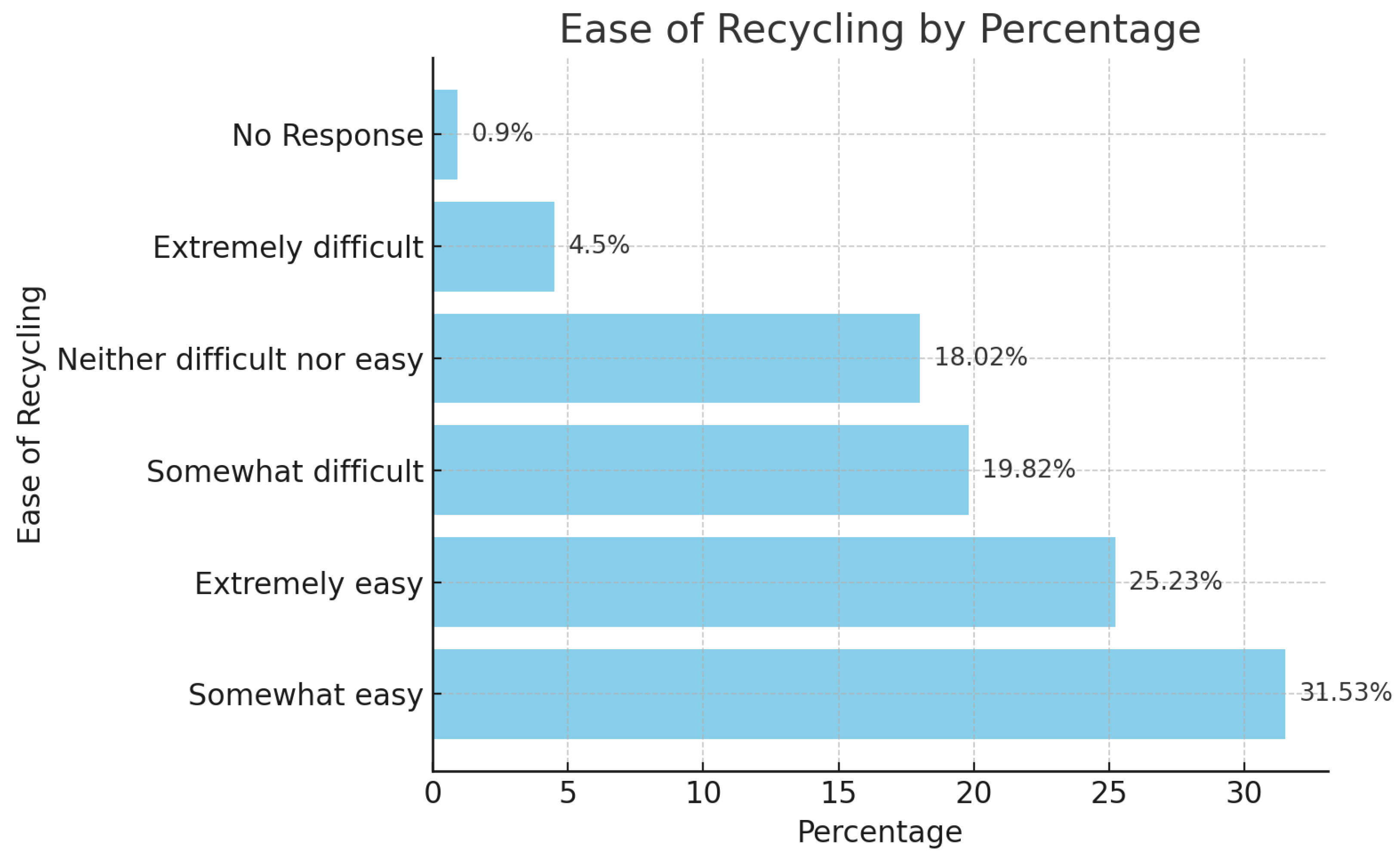

The responses to the question “How easy/difficult is it to recycle in Glendale?” show that a significant majority of respondents found recycling to be relatively easy (Table 2 and Figure 2). Specifically, 35 respondents (31.53%) indicated that recycling is “somewhat easy”, and 28 respondents (25.23%) found it “extremely easy”. In contrast, fewer participants reported difficulties with recycling: 22 respondents (19.82%) found it “somewhat difficult”, and five respondents (4.50%) found it “extremely difficult”. Additionally, 20 respondents (18.02%) felt that recycling was “neither difficult nor easy”, reflecting a neutral stance. There was one respondent (0.90%) who did not provide a response. These data suggest that while most residents find recycling to be manageable, there remains a notable portion of the population that encounters challenges, indicating areas for potential improvement in Glendale’s recycling program.

Table 2.

Ease of Recycling.

Figure 2.

Ease of Recycling.

3.2. Households Size

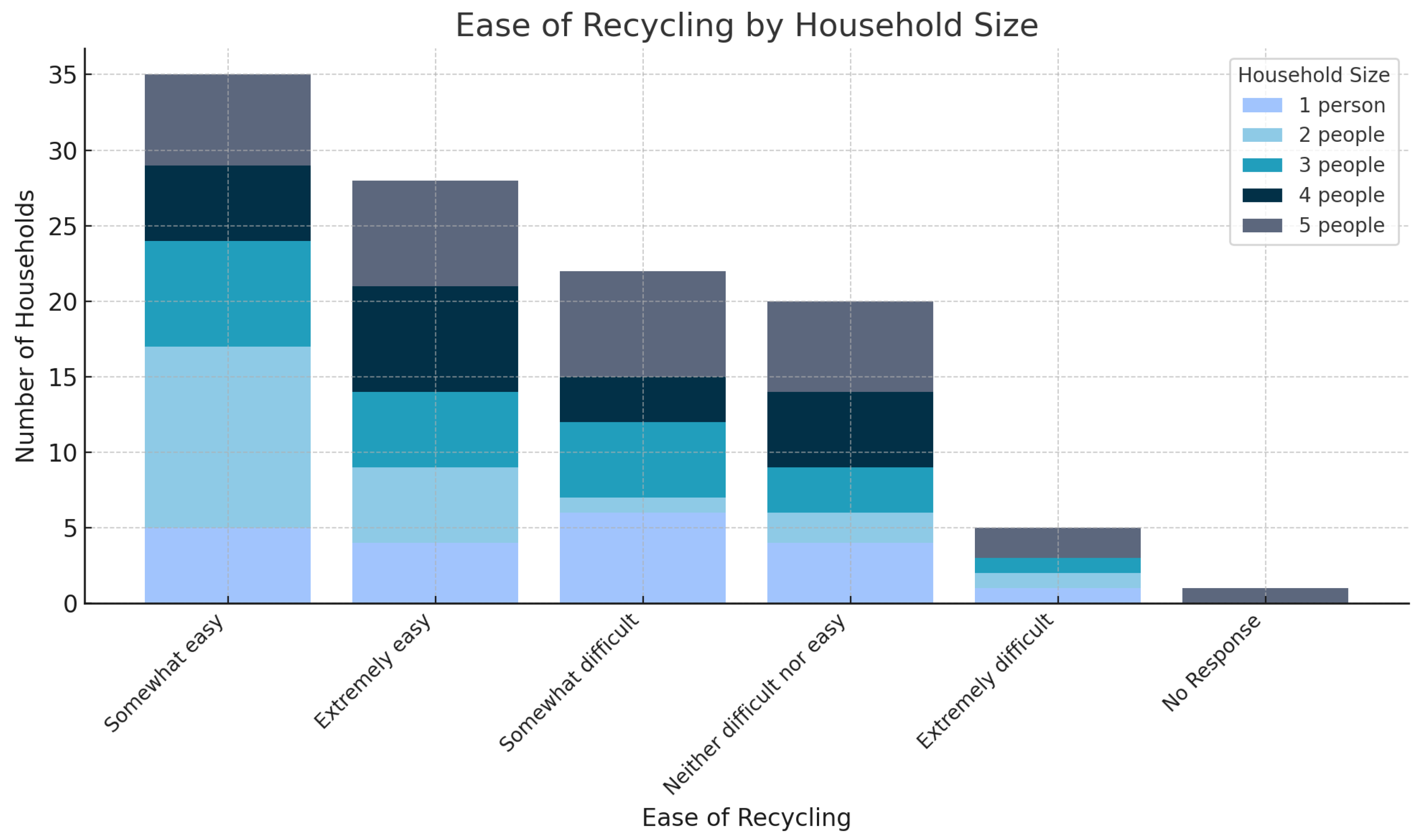

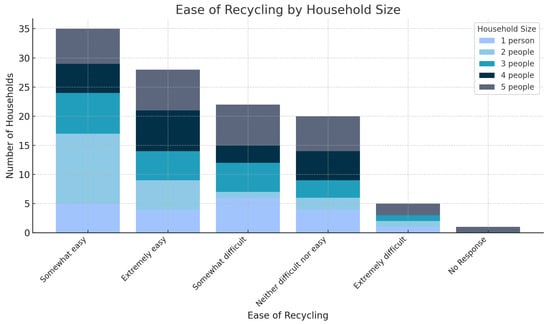

Table 3 shows the relationship between the ease of recycling and household size. It appears that larger and single-person households have varied experiences regarding the ease of recycling. Table 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the relationship between the ease of recycling and household size in Glendale. The data revealed varied experiences across different household sizes. For single-person households, five respondents found recycling “somewhat easy”, four “extremely easy”, and six “somewhat difficult”. Two-person households had the highest number of respondents (12) finding recycling “somewhat easy”, with five finding it “extremely easy” and only one finding it “somewhat difficult”. Three-person households reported seven respondents finding recycling “somewhat easy”, five “extremely easy”, and five “somewhat difficult”. Four-person households had five respondents, each finding recycling “somewhat easy” and “neither difficult nor easy”, with seven finding it “extremely easy” and three finding it “somewhat difficult”. Larger households (5 or more people) had six respondents finding recycling “somewhat easy”, seven “extremely easy”, and seven “somewhat difficult”.

Table 3.

Ease of Recycling vs. Household Size.

Figure 3.

Ease of Recycling vs. Household Size.

Overall, the highest ease of recycling was reported by two-person households, whereas difficulty was more frequently noted by single-person households and those with five or more members. A small number of respondents (five) found recycling “extremely difficult”, with a slight concentration in larger households. Only one respondent did not provide an answer, coming from a household with five or more members. These findings suggest that household size significantly influences the perceived ease of recycling, with both single-person and larger households facing unique challenges. This highlights the need for targeted interventions to address the specific needs of different household sizes to improve recycling rates and efficiency in Glendale.

The analysis below shows responses from one single-person household, revealing several recurring themes. One person’s household often generates less waste overall, including recyclables. This smaller volume can lead to infrequent recycling trips, making it less of a routine activity. A participant said, “I do not accumulate enough recyclables to make frequent trips to the recycling center worthwhile”. Limited space in smaller households can restrict the ability to store recyclables until they are taken to a recycling facility. This is particularly problematic in apartments or homes without designated storage areas. One participant said, “I do not have enough space to store recyclables for long. My apartment is too small”. Individuals in smaller households may feel that their contribution to recycling is minimal and, therefore, less impactful, reducing their motivation to recycle diligently. A resident expressed, “It feels like my small amount of recycling does not make a difference”. The convenience and accessibility of recycling facilities remain significant barriers. Smaller households, especially those without private transportation, may find it challenging to access recycling centers. A respondent explained: “The recycling center is too far, and I do not have a car. It is hard to get there”. There is often a lack of awareness about what can be recycled and how to recycle various materials properly. This confusion can discourage consistent recycling practices. One participant expressed, “I am not sure what I can recycle. There are so many rules, and it is confusing. The absence of economic incentives for recycling can be a disincentive for smaller households. Without financial rewards or subsidies, the effort required may not seem justified, as one person said no incentive to recycle. It would help if we got some kind of reward for it”.

3.3. Household Income

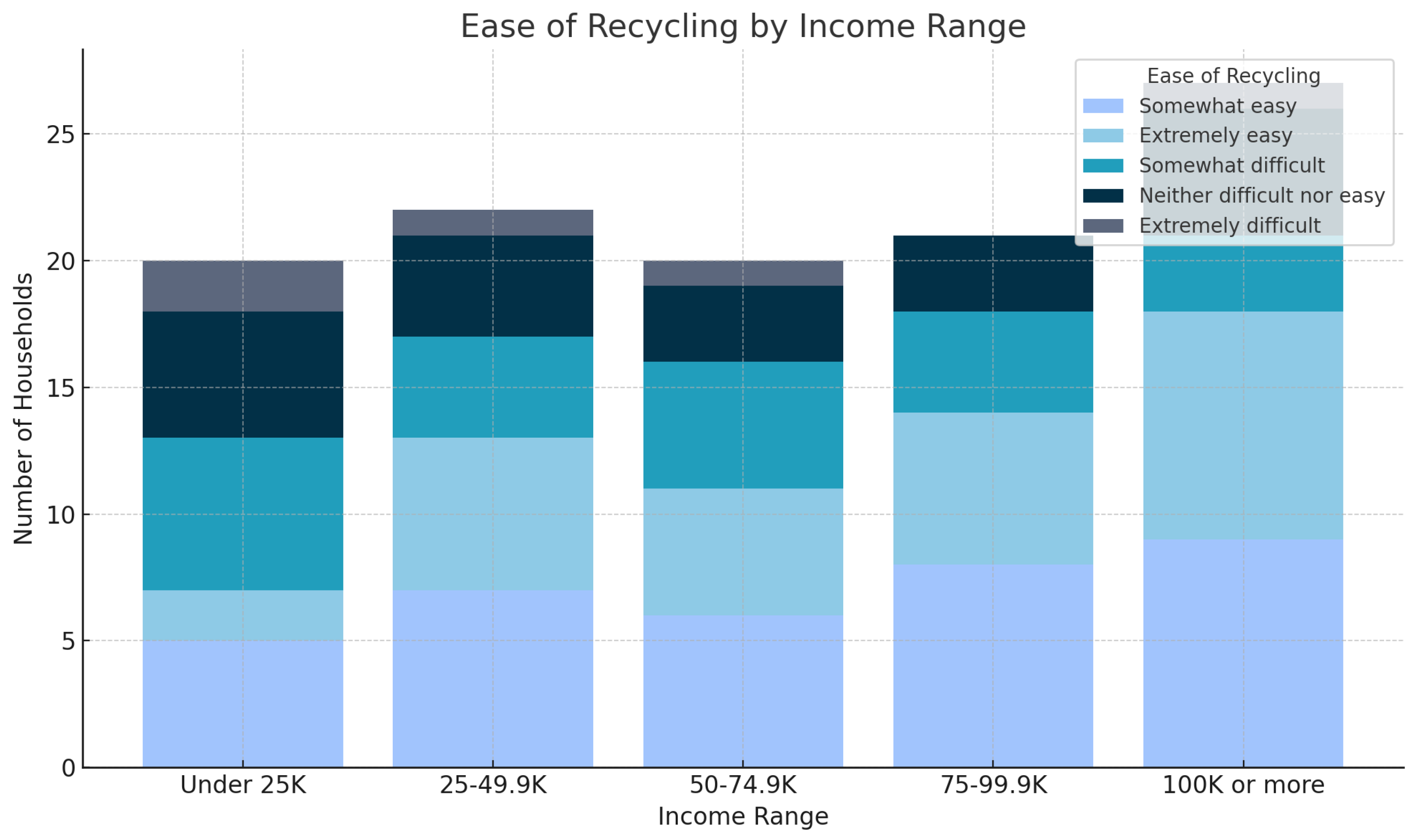

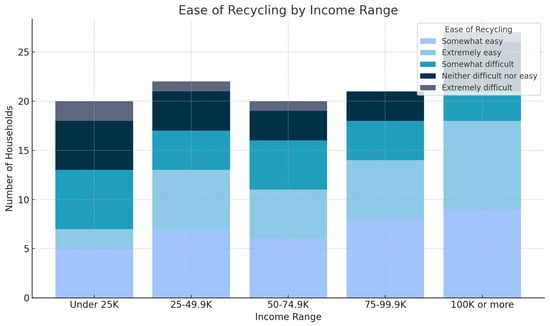

Table 4 and Figure 4 illustrate the relationship between the ease of recycling and household income in Glendale. The data showed that higher-income households generally find recycling easier, with nine respondents in the USD 100,000 or more bracket finding it “somewhat easy” and “extremely easy”. In contrast, lower-income households, particularly those earning under USD 25,000, report more difficulties, with six finding recycling “somewhat difficult” and two finding it “extremely difficult”. This indicates that higher-income households benefit from better access to recycling facilities and services, while lower-income households face significant barriers such as limited access and a lack of curbside pickup. Addressing these disparities can improve overall recycling participation in Glendale.

Table 4.

Ease of Recycling vs. Income in 2021.

Figure 4.

Ease of Recycling vs. Income in 2021.

A higher-income household reported, “We have a robust recycling system in our neighborhood, and it is quite straightforward”. Meanwhile, a low-income resident shared, “Recycling is challenging because the nearest facility is too far, and there is no curbside pickup in our area”. Higher-income residents have better access to recycling facilities, including curbside pickup services, and a greater likelihood of living in areas with more established recycling infrastructure. A higher-income participant expressed, “Our area has regular curbside pickup, making it very convenient”. However, lower-income residents have limited access to recycling facilities and services. They often reside in areas without regular curbside pickup or convenient drop-off points. One resident pointed out, “We have to drive a long distance to find a recycling center, which is not practical”.

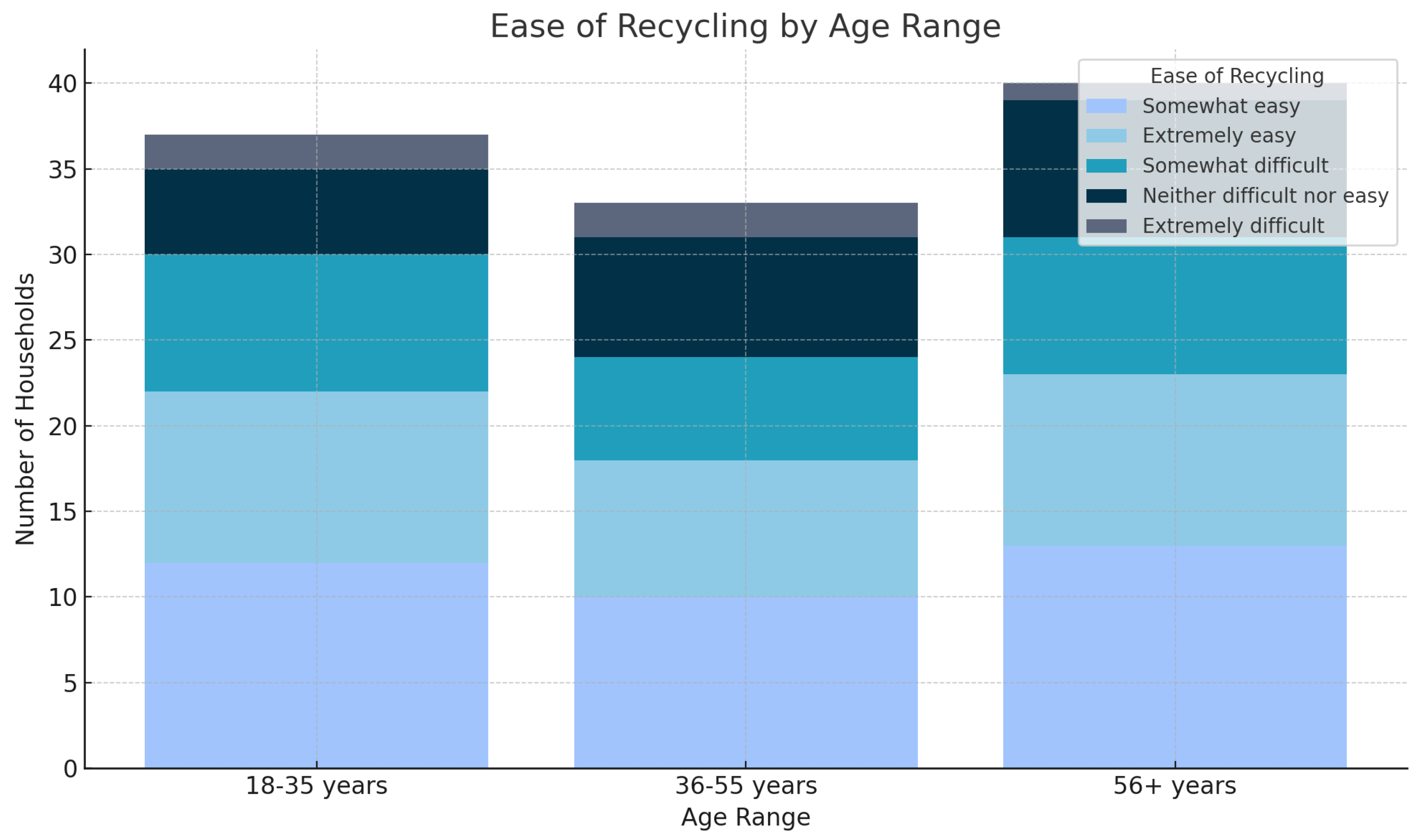

3.4. Age

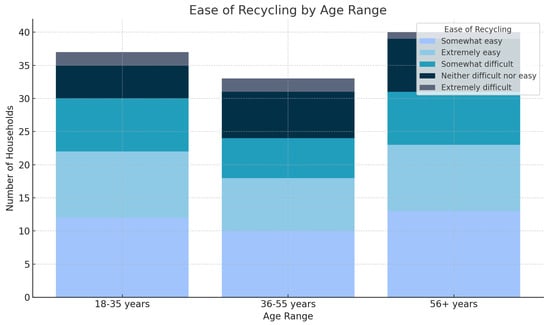

Table 5 and Figure 5 illustrate the relationship between the ease of recycling and different age groups in Glendale. The data showed varied experiences across the age spectrum, indicating distinct challenges and perceptions related to recycling. Among young adults (18–35 years), 12 respondents found recycling “somewhat easy”, while ten found it “extremely easy”. However, eight young adults reported it as “somewhat difficult”, and two found it “extremely difficult”. One young adult did not provide a response. Middle-aged adults (36–55 years) had ten respondents finding recycling “somewhat easy” and eight finding it “extremely easy”, six reported it as “somewhat difficult”, and two found it “extremely difficult”. None from this age group left the question unanswered. Older adults (56 years or older) had 13 respondents finding recycling “somewhat easy”, and ten finding it “extremely easy”, but eight reported it as “somewhat difficult”, and only one found it “extremely difficult”.

Table 5.

Ease of Recycling vs. Age.

Figure 5.

Ease of Recycling vs. Age.

These data suggest that older adults generally find recycling “somewhat” or “extremely easy”, though they also face challenges due to physical constraints. Young and middle-aged adults show a balanced distribution across ease and difficulty levels, indicating mixed experiences. The consistent number of respondents finding recycling “somewhat difficult” across all age groups highlights common challenges faced by residents. Additionally, a notable portion of respondents in each age group finds recycling “neither difficult nor easy”, reflecting a neutral stance. These insights emphasize the need for targeted interventions to address specific barriers faced by each age group, improving overall recycling participation in Glendale.

Young adults, especially those living in apartments, report limited space for storing recyclables. Busy schedules and work commitments reduce the time available for recycling activities. Although generally aware, they seek more information on specific recycling practices. A survey respondent said, “I want to recycle, but my apartment does not have enough space for separate bins”. Rental properties, especially those managed by landlords or property management companies, frequently do not provide sufficient recycling facilities. Tenants may find that their buildings lack designated recycling bins or convenient drop-off points. As one young adult expressed, “My building does not have recycling bins, and I do not have a car to take recyclables to a center”. This lack of infrastructure discourages regular recycling practices and contributes to higher waste generation. Financial constraints also play a crucial role in limiting recycling efforts among young adults. Many are balancing student loans, entry-level job salaries, and other financial responsibilities, making additional expenses for recycling less feasible. For example, some young adults might need to purchase separate bins or bags for recyclables, pay for recycling services, or bear the costs of transporting recyclables to distant centers. One respondent highlighted this issue, stating, “Recycling services cost extra, and I cannot afford it right now”. The added financial burden can be a significant deterrent, especially for those already struggling to manage their budgets.

Middle-aged adults (36–55 years) exhibit consistent recycling habits influenced by family routines and community norms. Some middle-aged adults find recycling facilities inconveniently located. The complexity of sorting the different types of recyclables can be a deterrent. There is a desire for financial incentives to encourage more diligent recycling, as one participant said, “Recycling is part of our routine, but it would be easier if the center were closer”.

Older Adults (56 years or older) often show a strong commitment to recycling, driven by a long-term perspective on environmental conservation. Physical challenges can make it difficult to transport recyclables to collection points. There is a need for assistance or more accessible facilities, as well as a desire for clear and simple information on recycling practices. This is exemplified by the quote, “I try to recycle everything I can, but it is hard to carry heavy bags”. Another older adult said, “I do not drive, so I cannot go to the recycling stations”.

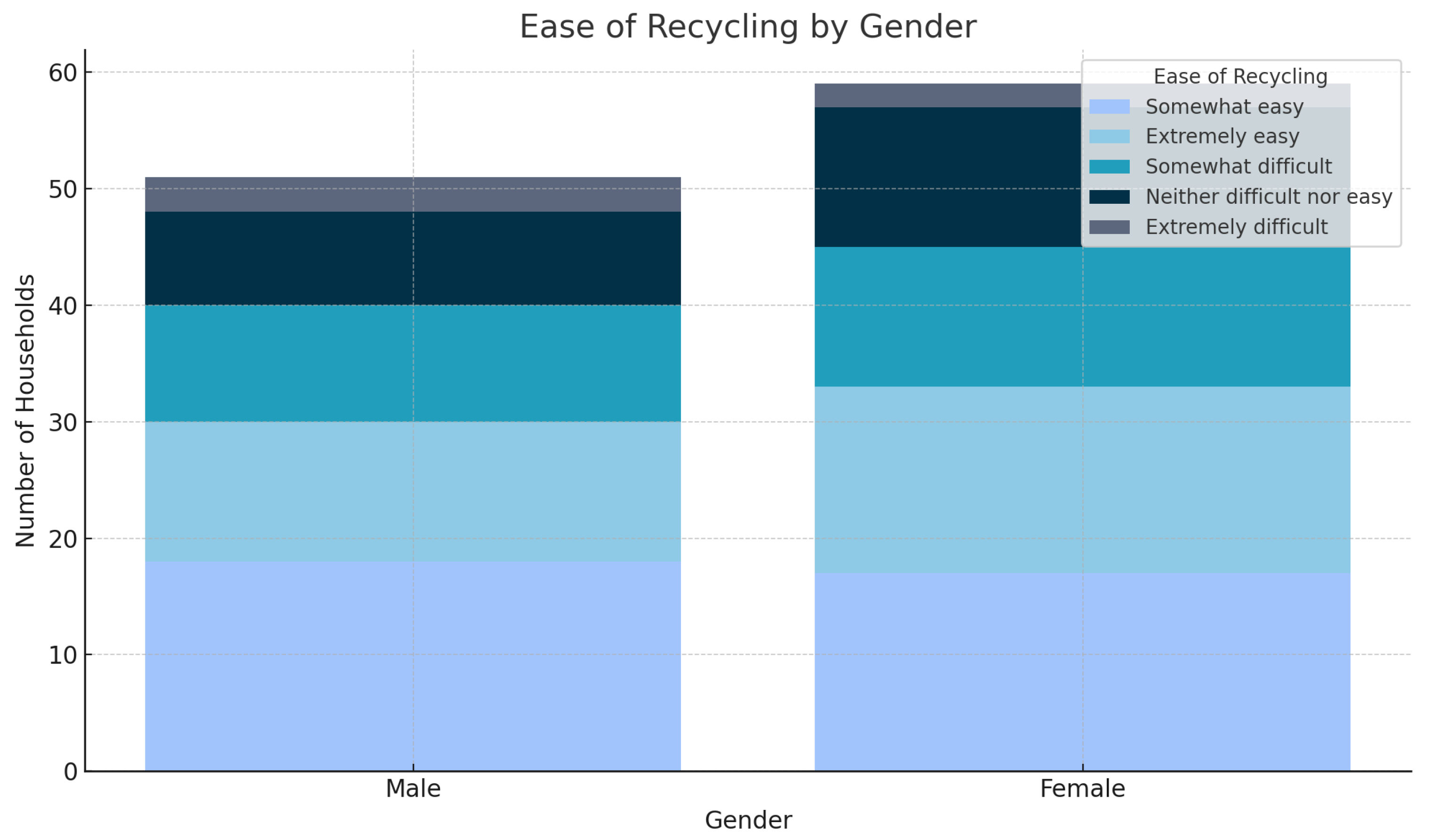

3.5. Gender

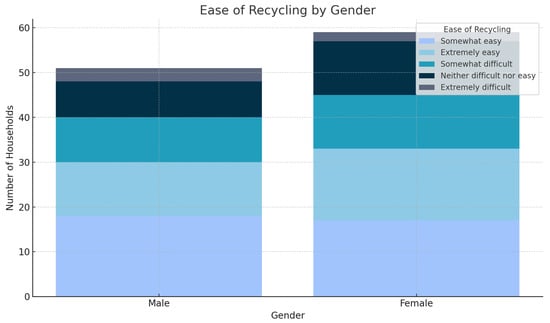

Figure 6 shows that among males, 18 respondents found recycling “somewhat easy”, and 12 found it “extremely easy” (Table 6). However, ten males reported recycling as “somewhat difficult”, and three found it “extremely difficult”. Additionally, eight males found it “neither difficult nor easy”, and there was one male who did not respond.

Figure 6.

Ease of Recycling vs. Age.

Table 6.

Ease of Recycling vs. Age.

For females, 17 respondents found recycling “somewhat easy”, and 16 found it “extremely easy”, indicating a slightly higher ease of recycling compared to males. Twelve females reported recycling as “somewhat difficult”, and two found it “extremely difficult”. Moreover, 12 females found it “neither difficult nor easy”, and no females left the question unanswered.

Overall, the data suggest that both genders have similar experiences with recycling, with a slight tendency for females to find recycling easier. Both groups have notable numbers reporting recycling as “somewhat difficult”, highlighting common challenges faced by residents. The distribution of responses across categories shows that while many find recycling easy, significant portions of both genders face difficulties, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions to improve recycling ease for all residents in Glendale.

Women tend to have higher levels of environmental awareness and concern. A mother expressed, “Recycling is a routine part of our household chores”. This is often tied to their role in managing household chores and setting examples for their children. One participant explained, “I make sure we separate our recyclables every day. It is something I have taught my kids to do as well. It is just part of our routine now”. Another echoed this sentiment, saying, “Recycling is important for our planet, and I want to make sure my children understand that”. Women are motivated by the desire to contribute positively to the environment and to teach their children the importance of sustainable practices. One mother shared, “Recycling is a routine part of our household chores. I want to set a good example for my kids and show them how small actions can make a big difference”. Women face fewer logistical and motivational barriers but express frustration when other household members do not share their level of commitment. A respondent noted, “It is frustrating when I see recyclables in the trash because my husband or kids did not bother to sort them. It feels like all my effort is wasted”.

Men show moderate participation rates in recycling programs, often viewing it as an optional activity rather than a necessary household chore. Men are less consistent in their recycling efforts, prioritizing it only when convenient and easy. One participant stated, “I recycle when it is convenient, but it is not a priority for me”. Another added, “I know recycling is important, but sometimes it is just too much hassle to sort everything. I am the one that manages the garbage and takes out the garbage, and I see my family does not put an effort into doing it right, so why bother?” Men face significant barriers, such as a lack of convenient recycling facilities and time constraints. They are also more likely to be influenced by the perceived effort and benefits of recycling. One respondent mentioned, “The nearest recycling center is too far, and I do not have time to make special trips just to drop off certain kinds of recyclables”. Another pointed out, “If there were more convenient drop-off points or if we had a curbside pickup, I would probably recycle more”. Economic incentives and convenience play a crucial role in motivating men to recycle. Without these factors, their participation tends to be lower compared to women. A male participant suggested, “If there were some kind of financial incentive or rebate for recycling, I would definitely be more diligent about it”.

3.6. Overall Barriers to Recycling

The analysis of open-ended responses regarding barriers to recycling reveals common themes. For example, 26 respondents indicated a shortage of dedicated glass recycling facilities. Unlike plastic or paper, which have more widespread recycling options, glass recycling points were often reported as inaccessible or non-existent. One of the respondents said, “There are no convenient places to recycle glass. Most recycling centers around here do not accept glass”. The perceived effort and time required to prepare glass for recycling (cleaning, sorting by color) discourage residents from recycling glass. One Glendale resident said, “Cleaning and sorting glass takes too much time. It is easier to just throw it away”. Respondents frequently mentioned that even when facilities are available, they are often inconveniently located, requiring significant travel. For example, a participant mentioned, “The nearest glass recycling facility is too far away. It is not practical for me to drive that far just to recycle a few bottles”. There is a notable deficiency in public information regarding what types of glass can be recycled and where to recycle them. This confusion leads to lower participation rates. One responded expressed, “I am not sure if my glass bottles can be recycled. I have heard different things from different sources”. Common barriers included a lack of clear information on recyclable materials and inadequate facilities. Some concerns about contamination, where non-recyclable materials are mixed with glass, were also highlighted. This issue brings worries among those who recycle about entire batches of recyclables being discarded. A participant expressed, “I have heard that if the glass is mixed with other trash, it all goes to the landfill anyway. It feels pointless”. Furthermore, the economic viability of glass recycling was questioned, with some residents feeling that there is insufficient financial incentive for municipalities to invest in glass recycling programs. A survey respondent said, “I do not think the city prioritizes glass recycling because it is not cost-effective”.

Respondents frequently mentioned specific areas plagued by litter, suggesting the need for focused waste management strategies in these regions.

4. Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the recycling behaviors of Glendale residents, highlighting the importance of addressing community-specific issues to enhance recycling rates. Our findings look at sociodemographic factors such as household size, income, gender, and age, which significantly influence recycling behaviors, aligning with previous research on the subject [5]. However, this study adds a localized perspective, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions to address unique community challenges.

The variation in recycling ease across different household sizes suggests that personalized approaches may be more effective. Smaller households face significant barriers due to limited storage space and a perceived lack of impact, which is consistent with Deshpande et al. (2024), who highlighted similar challenges for lower-income households [9]. This study extends these findings by demonstrating that smaller households, regardless of income, find recycling harder than low-income households. Larger households with more established routines still encounter logistical challenges that require tailored solutions.

Socioeconomic disparities also play a crucial role in recycling behaviors. Higher-income households benefiting from better access to facilities and greater awareness exhibit higher participation rates. This aligns with Schultz et al. (1995), who found that higher income was a significant predictor of recycling [12]. However, this study provides a nuanced view by revealing that lower-income households face significant barriers, such as limited facility access and insufficient information, emphasizing the need for equitable access and targeted educational campaigns.

Gender differences in recycling habits are well-documented, with women generally exhibiting higher participation rates and a stronger sense of moral responsibility towards recycling [16]. This study confirms these trends within the Glendale community and highlights the specific frustrations women face when household members do not share their commitment. Men, showing moderate participation rates and being more influenced by convenience and economic incentives, require targeted strategies to enhance their recycling efforts. This finding underscores the need to improve the convenience of recycling facilities and introduce economic incentives to increase male participation.

Age is another significant factor influencing recycling behaviors. Younger adults demonstrate high environmental awareness but face practical challenges such as limited space and busy lifestyles. This study supports previous research indicating that younger individuals are environmentally conscious but less likely to engage in certain recycling activities due to these constraints [12]. Middle-aged adults, influenced by family routines and community norms, seek more convenient facilities, while older adults face physical challenges that hinder their ability to recycle despite their strong commitment. These findings suggest the need for age-specific interventions to address these unique barriers.

This study also identifies systemic issues within the recycling infrastructure and public education, particularly concerning glass recycling. The lack of accessible facilities and clear information are significant deterrents, reflecting a broader need for streamlined and user-friendly recycling processes. These findings align with broader research indicating that convenience and information are critical factors in recycling behaviors [5]. However, the specific focus on glass recycling highlights unique challenges that are less prevalent with other materials, suggesting that dedicated glass recycling facilities and better public information could significantly improve participation rates.

Furthermore, the economic viability of glass recycling was questioned by respondents, with some feeling that there is insufficient financial incentive for municipalities to invest in glass recycling programs. Addressing these economic concerns and improving infrastructure could enhance glass recycling rates and overall sustainability, providing a new dimension to the existing body of research on the economic aspects of recycling.

One notable point highlighted in this research is how behavioral interventions can positively influence recycling participation. Tailoring nudges based on the motivations and barriers of groups could effectively promote recycling. For instance, social norm campaigns showcasing peer recycling rates could inspire adults who tend to follow peer behavior trends. Moreover, households facing convenience challenges could benefit from reminders or small incentives for easy recycling tasks to establish habits. Leveraging platforms to offer real-time feedback on recycling efforts and their environmental impact may resonate well with younger tech individuals. By combining these tactics with the mentioned infrastructure enhancements, a holistic approach can be taken toward boosting recycling rates among various population segments in Glendale. These strategies could serve as a blueprint for communities dealing with demographic and environmental issues, contributing to the ongoing conversation on sustainable waste management practices.

In conclusion, this study contributes to understanding recycling behaviors by providing a detailed analysis of how household size, income, gender, and age influence recycling practices within a specific community. By addressing the unique barriers faced by different demographic groups through targeted interventions, Glendale can improve recycling participation rates, reduce waste, and foster a culture of sustainability. These efforts will benefit the environment and create a more inclusive and efficient recycling program for all residents, offering valuable insights for other urban areas with similar demographic challenges.

5. Conclusions

Several research studies have looked at factors separately or generalized across larger areas. It is important to conduct localized studies that consider how various sociodemographic factors interact to understand better how they collectively impact recycling behaviors. This study aims to address this gap by examining the recycling practices of residents in Glendale. It delves into how factors like household size, age, income, and gender influence recycling participation and identifies obstacles and motivators within the community. By focusing on Glendale, this research can offer insights directly relevant to local decision-makers and those designing recycling programs.

The findings of this study shed light on the difficulties and perspectives surrounding recycling in the Glendale area. They underscore the importance of raising awareness, expanding recycling facilities, and implementing targeted waste management strategies. One of the recommendations is to boost efforts in educating residents about materials and recycling methods. A suggestion is to launch public education campaigns that inform residents about glass types and where they can find recycling facilities. Additionally, utilizing communication channels such as social media, local news outlets, and community gatherings can help spread this information effectively.

It is important to inform the public about contamination concerns and offer guidance on how to avoid issues. One idea is to enhance the sorting systems at recycling centers to manage contamination better.

Another suggestion is to invest in recycling facilities for glass. Salt Lake City could enhance the availability of glass recycling locations in areas through partnerships with local businesses for drop-off spots. Simplifying the glass recycling process by minimizing cleaning and sorting requirements, along with providing instructions on how to prepare glass items for recycling, could be beneficial.

A third proposal involves exploring incentives for residents and local governments to prioritize glass recycling. This might involve implementing deposit refund programs for glass bottles or offering subsidies for recycling facilities. Lastly, it would be beneficial to implement targeted waste management strategies in littering areas.

Addressing the challenges of glass recycling calls for an approach that includes expanding infrastructure, educating the public, and introducing incentives. By addressing these issues, Glendale can boost its glass recycling rates and contribute to creating a sustainable community.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Utah (protocol code 00119632, approved on 28 August 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Example of the Email Survey Request.

Figure A1.

Example of the Email Survey Request.

References

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 12: Ensure Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. Waste Management Strategies for Sustainable Development. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 2020–2028. ISBN 978-3-030-11352-0. [Google Scholar]

- Vining, J.; Linn, N.; Burdge, R.J. Why Recycle? A Comparison of Recycling Motivations in Four Communities. Environ. Manag. 1992, 16, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, S. Waste Separation at Home: Are Japanese Municipal Curbside Recycling Policies Efficient? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and Social Factors That Influence Pro-environmental Concern and Behaviour: A Review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Investigate the Determinants of Recycling Behaviour: A Case Study from Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttibak, S.; Nitivattananon, V. Assessment of Factors Influencing the Performance of Solid Waste Recycling Programs. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 53, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidique, S.F.; Lupi, F.; Joshi, S.V. The Effects of Behavior and Attitudes on Drop-off Recycling Activities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.; Ramanathan, V.; Babu, K.; Deshpande, A.; Ramanathan, V.; Babu, K. Assessing the Socio-Economic Factors Affecting Household Waste Generation and Recycling Behavior in Chennai: A Survey-Based Study. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 11, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, O.; Söderholm, P.; Berglund, C. Norms and Economic Motivation in Household Recycling: Empirical Evidence from Sweden. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2009, 53, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Mohiuddin, M.; Ahmad, G.B.; Thurasamy, R.; Fazal, S.A. Recycling Intention and Behavior among Low-Income Households. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Oskamp, S.; Mainieri, T. Who Recycles and When? A Review of Personal and Situational Factors. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, R.; Randell, A.; Lavoie, S.; Gao, C.X.; Manrique, P.C.; Anderson, R.; McDowell, C.; Zbukvic, I. Empirical Evidence for Climate Concerns, Negative Emotions and Climate-Related Mental Ill-Health in Young People: A Scoping Review. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2023, 17, 537–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S.D.; Pihkala, P.; Wray, B.; Marks, E. Psychological and Emotional Responses to Climate Change among Young People Worldwide: Differences Associated with Gender, Age, and Country. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, B.; Frey, B.S.; Wilson, C. Environmental and Pro-Social Norms: Evidence on Littering. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2009, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Guilbert, S.; Metcalfe, A.; Riley, M.; Robinson, G.M.; Tudor, T.L. Beyond Recycling: An Integrated Approach for Understanding Municipal Waste Management. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 39, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Balázs, B.; Mónus, F.; Varga, A. Age Differences and Profiles in Pro-Environmental Behavior and Eco-Emotions. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2024, 48, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.; Ford, N. Defining the Multi-Dimensional Aspects of Household Waste Management: A Study of Reported Behavior in Devon. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2005, 45, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikimedia Commons. Huebi~Commonswiki Map of USA with Utah Highlighted. 2006. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_USA_UT.svg (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Benbennick, D. Map of Utah Highlighting Salt Lake County. 2006. Available online: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Utah_highlighting_Salt_Lake_County.svg (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Google Maps: Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 2024. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/dir/Salt+Lake+City (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- ERSI. Map of Glendale; ESRI: Redlands, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- American Community Survey. Population Estimates; U.S. Census: Suitland, MD, USA, 2015.

- Recycling Drop-Off Locations. Available online: https://www.slc.gov/sustainability/waste-management/recycling-drop-off-locations/ (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- High Speed Internet Providers in Glendale, Salt Lake City, UT. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20241004085933/https://ispreports.org/internet-service-providers-glendale-salt-lake-city-ut/ (accessed on 22 September 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).