Knowledge Management in Serbian SMEs: Key Factors of Influence on Internal and External Business Performances

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

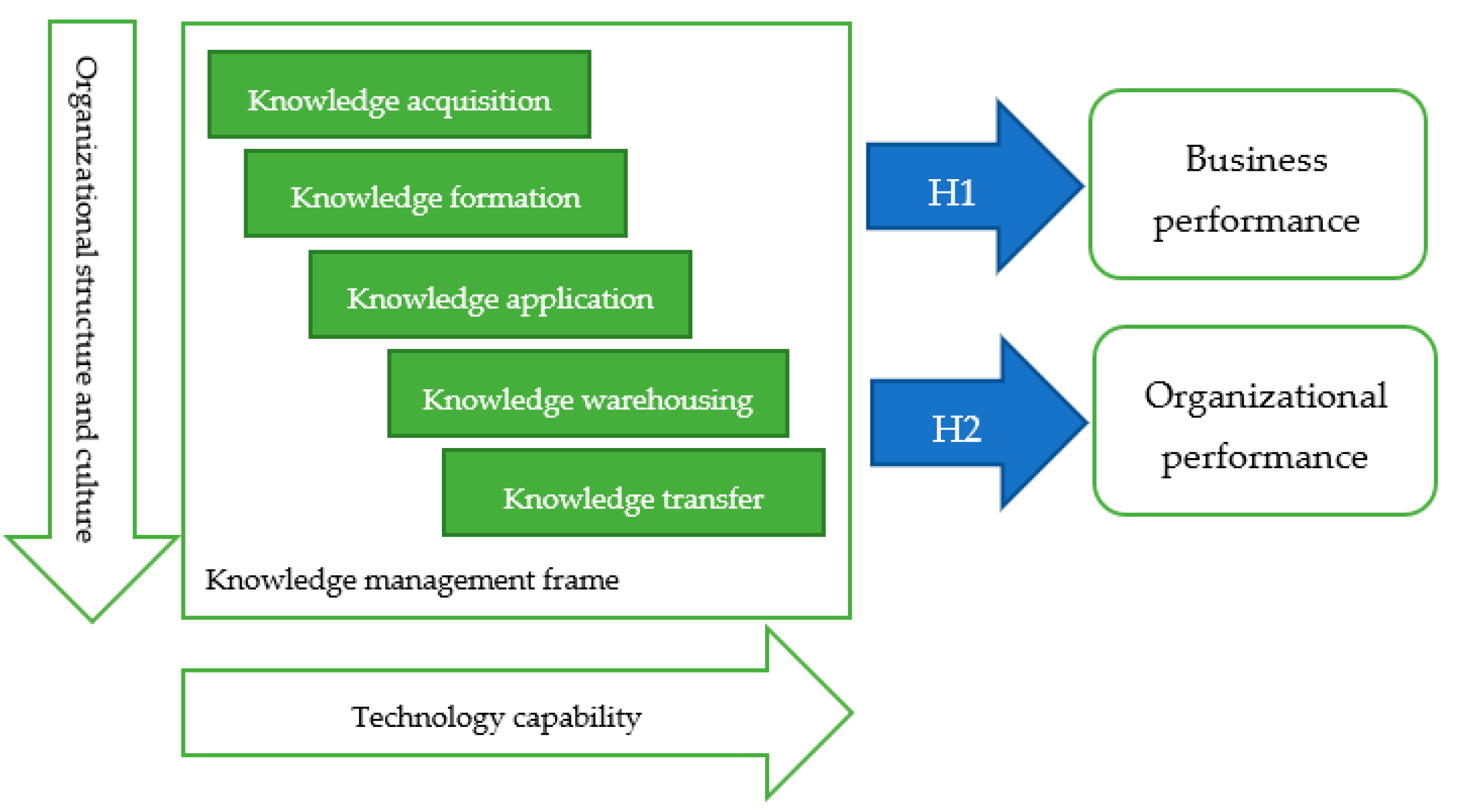

2.1. Process Capability for Knowledge Management Adoption

2.2. Infrastructure Capability for Knowledge Management Exploitation

2.3. Research Hypothesis Formulation

3. Methodological Framework

3.1. Research Elements

3.2. Research Methodology

- Effectiveness—measured through annual revenue amount;

- Internal productivity—measured by annual operating cost of doing business.

- Standardization;

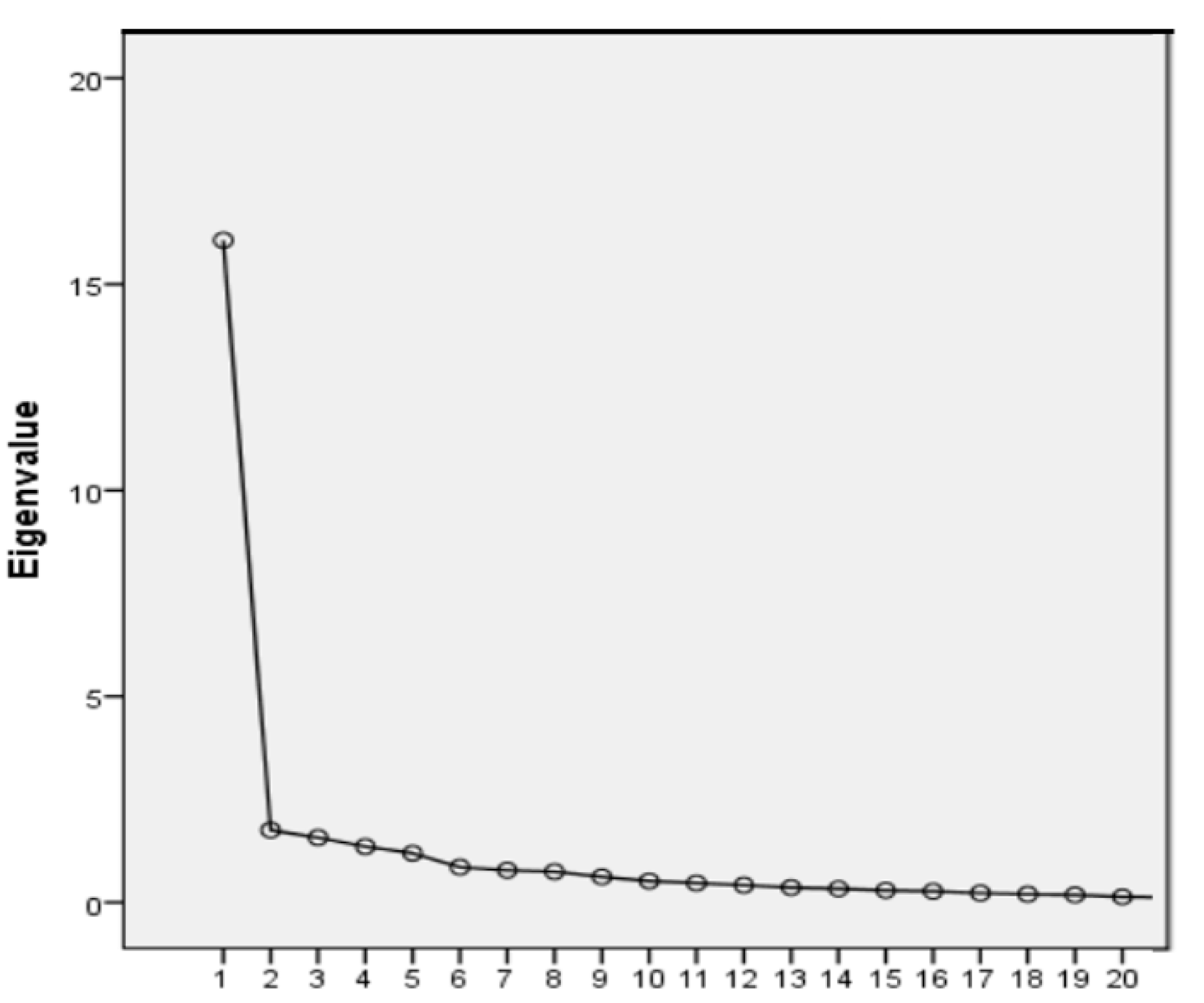

- Calculation of covariance matrix;

- Eigenvalue and eigenvector calculation;

- Selection of principal (key) components;

- Transformation;

- Identifying key drivers and simplifying models;

- Visualizing relationships and interpreting results.

- β0 is the intercept;

- βi (i = 1, …, n) are the coefficients for individual KM dimensions;

- βj (j = 1, …, m) are the coefficients for interaction term;

- ϵ is the error term.

- Variable Selection: Identify relevant independent variables based on theoretical frameworks or empirical evidence. Consider factors like multicollinearity and variable significance.

- Model Specification: Formulate the regression model by specifying the relationship between the dependent variable and chosen independent variables. Define the functional form and include interaction terms if necessary.

- Estimation and Interpretation: Use statistical software to estimate regression coefficients. Interpret the coefficients to understand the impact of each independent variable on the dependent variable. Assess model fit through diagnostics like R-squared and residuals.

3.3. Survey Description and Sample Definition

3.4. Knowledge Management Factors and Dimensions

4. Results

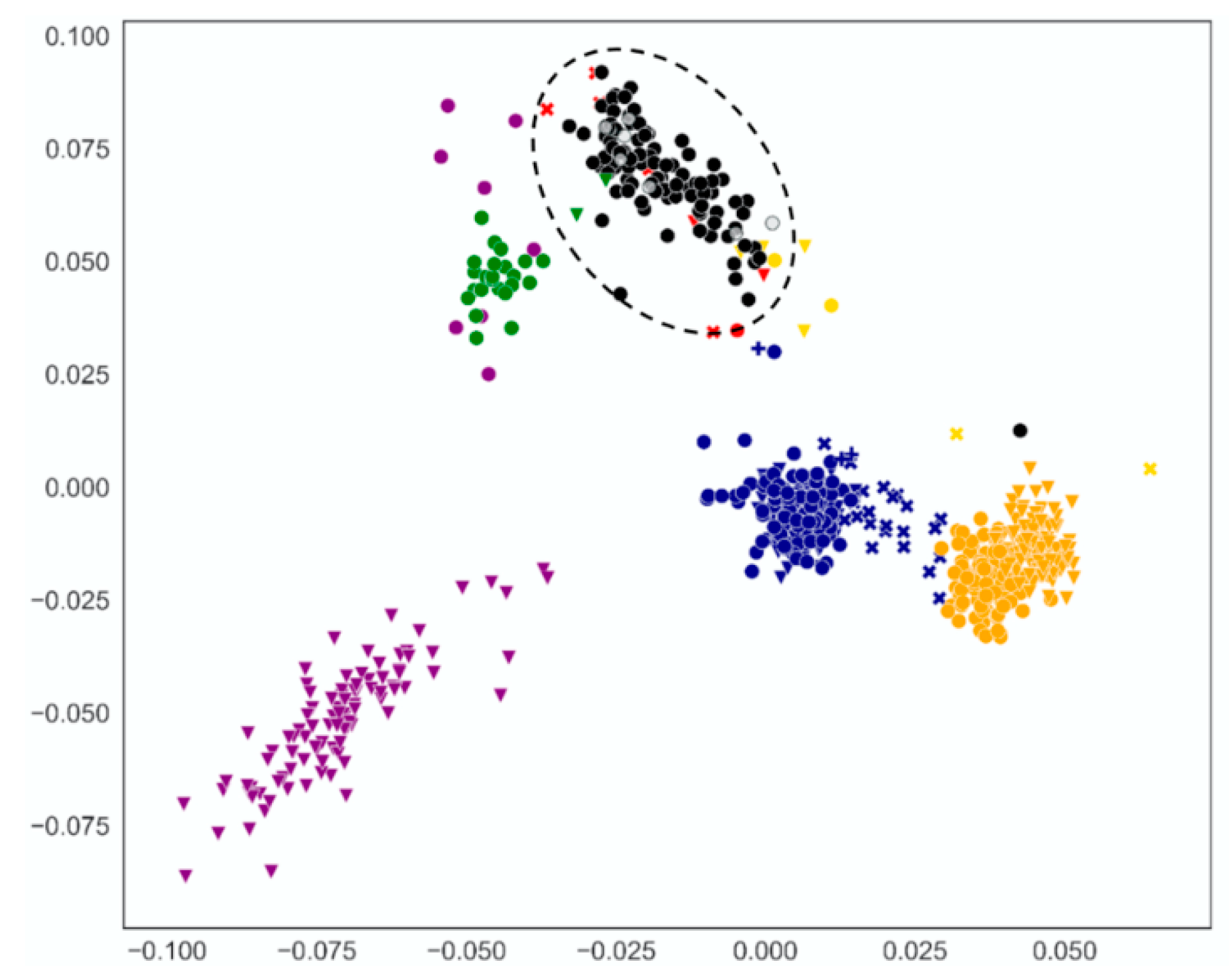

4.1. Research Findings

- Business consultancy;

- Existence of a separate data officer and data management team;

- Assembled critical team of KM experts;

- Knowledge governance (data about data);

- Sharing of best practices and cocreation.

4.2. Testing Research Hypotheses

5. Discussion

- Theoretical examination of process and technology capabilities for knowledge management adoption and exploitation;

- Results of quantitative research involving analysis of the key influence of knowledge management factors on both internal and external business performances.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Freq. | % of Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Company size | Small | 248 | 67% |

| Medium | 122 | 33% | |

| Country of origin | Serbia | 247 | 67% |

| EU | 120 | 32% | |

| Rest of world | 3 | 1% | |

| No. of years doing business | 1–5 | 37 | 10% |

| 6–15 | 215 | 59% | |

| 16–25 | 68 | 18% | |

| 26+ | 50 | 13% | |

| Industry | Manufacturing | 220 | 59% |

| Services | 120 | 32% | |

| Combined | 30 | 19% | |

| Annual revenue range | Less than EUR 10 million | 285 | 77% |

| From EUR 10 to 50 million | 71 | 19% | |

| From EUR 50 to 100 million | 14 | 4% | |

| Knowledge acquisition | People are the carriers and mediums of new knowledge | 122 | 33% |

| Business consultancy—key driver for business acceleration | 88 | 24% | |

| Open two way communication is present | 90 | 24% | |

| Learning by doing—errors and mistakes are tolerated | 70 | 19% | |

| Knowledge formation | Existence of data officer and data management team | 134 | 36% |

| Knowledge formation tools are easy to use and maintain | 26 | 7% | |

| Line decision makers are devoting share of their time to KM | 110 | 30% | |

| KM procedures and rules are established and maintained | 100 | 27% | |

| Knowledge application | There exists an assembled critical team of KM experts | 86 | 23% |

| Knowledge is used in products/services innovation | 67 | 18% | |

| Knowledge is accessible to the whole company | 78 | 21% | |

| Data literacy is a process that ensures we apply knowledge the right way | 139 | 38% | |

| Knowledge warehousing | There exists knowledge governance (data about data) | 198 | 54% |

| Data dictionary is set up | 122 | 33% | |

| Data ownership process is established | 38 | 10% | |

| Data lineage in reporting process is easy to follow | 12 | 3% | |

| Knowledge transfer | Sharing of best practices and cocreation | 156 | 42% |

| Knowledge sharing is embedded in each project in the company | 68 | 18% | |

| We have standardized procedures for knowledge transfer | 76 | 21% | |

| Mentorships present a standard practice in the company | 70 | 19% | |

References

- Tanriverdi, H. Information Technology Relatedness, Knowledge Management Capability, and Performance of Multibusiness Firms. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoni, A.; Zanin, F.; Corazza, G.; Paradisi, A. Knowledge Management and Performance Measurement Systems for SMEs’ Economic Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.; Ćelić, Đ.; Uzelac, Z.; Drašković, Z. Three pillars of knowledge management in SMEs: Evidence from Serbia. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Entrepreneurship and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs). 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes_en (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Edvardsson, I.R.; Durst, S. The benefits of knowledge management in small and medium-sized enterprises. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 81, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R. Enabling Sustainability in an Interconnected World: Toward Systems of Sustainability Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Chawinga, W.D.; Chipeta, G.T. A synergy of knowledge management and competitive intelligence: A key for competitive advantage in small and medium business enterprises. Bus. Inf. Rev. 2017, 34, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourides, P.; Longbottom, D.; Murphy, W. Excellence in knowledge management: An empirical study to identify critical factors and performance measures. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2003, 7, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D.E. Knowledge Management and Knowledge Management Systems: Conceptual Foundations and Research Issues. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.H.; Prusak, L. Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hislop, D. Linking human resource management and knowledge management via commitment: A review and research agenda. Empl. Relat. 2003, 25, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Lee, H. An empirical investigation of KM styles and their effect on corporate performance. Inf. Manag. 2003, 40, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennex, M.E. Knowledge Management in Modern Organizations; Information Science Reference 2008; Idea Group Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig, K.M. Knowledge Management: Where Did It Come from and Where Will It Go? Expert Syst. Appl. 1997, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Fernandez, I.; Sabherwal, R. Organizational knowledge management: A contingency perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 23–55. [Google Scholar]

- Holsapple, C.W.; Joshi, K.D. Knowledge management: A threefold framework. Inf. Soc. 2002, 18, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouza, K.C.; Awazu, Y. Knowledge management at SMEs: Five peculiarities. J. Knowl. Manag. 2006, 10, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawi, L.A.; McCarthy, R.V.; Aronson, J.E. Knowledge management and the competitive strategy of the firm. Learn. Organ. 2006, 13, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, A.; Holt, R. Knowledge, learning and small firm growth: A systematic review of the evidence. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rua, O.; França, A.; Fernández Ortiz, R. Key drivers of SMEs export performance: The mediating effect of competitive advantage. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzelac, Z.; Ćelić, Đ.; Petrov, V.; Drašković, Z.; Berić, D. Comparative analysis of knowledge management activities in SMEs: Empirical study from a developing country. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 17, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavalić, M.; Nikolić, M.; Stanisavljev, S.; Đorđević, D.; Pečujlija, M.; Terek Stojanović, E. Knowledge management and financial performance in transitional economies: The case of Serbian enterprises. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 22, 1436–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Edvardsson, I.R.; Foli, S. Knowledge management in SMEs: A follow-up literature review. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. Knowledge complexity and firm performance: Evidence from the European SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E.; Spadaro, M.R. The Spread of Knowledge Management in SMEs: A Scenario in Evolution. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10210–10232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceptureanu, S.; Ceptureanu, E. Knowledge Management Strategies for SMEs. In Entrepreneurship in United Europe—Challenges and Opportunities, Proceedings of the International Conference, Sunny Beach, Bulgaria, 13–17 September 2006, 1st ed.; Chapter 127; Conference Proceedings Chapters; Todorov, K., Smallbone, D., Eds.; Bulgarian Association for Management Development and Entrepreneurship: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2007; pp. 424–433. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, M.; Loebbecke, C.; Powell, P. SMEs, co-opetition, and knowledge sharing: The role of information systems. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2003, 12, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sytnik, N.; Kravchenko, M. Application of knowledge management tools: Comparative analysis of small, medium, and large enterprises. J. Entrep.Manag. Innov. 2021, 17, 121–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Handley, K.; Bagnoli, C.; Dumay, J. Knowledge management in small and medium enterprises: A structured literature review. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 258–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Muskat, B.; Creed, A.; Zutshi, A.; Csepregi, A. Knowledge sharing, knowledge transfer and SMEs: Evolution, antecedents, outcomes and directions. Pers. Rev. 2021, 59, 1873–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajnovic, A.; Covo, P.; Jasic, D. Knowledge management for small and medium sized enterprises—Whose concern is it? In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technology and Business Management, University of Zadar, Zadar, Croatia, 22 January 2012; pp. 726–733. [Google Scholar]

- Kiptalam, A.; Komene, J.J.; Buigut, K. Effect of knowledge management on firm competitiveness: Testing the mediating role of innovation in the small and medium enterprises in Kenya. Int. J. Small Bus. Entrep. Res. 2016, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Atkočiūnienė, Z.O.; Gribovskis, J.; Raudeliūnienė, J. Influence of Knowledge Management on Business Processes: Value-Added and Sustainability Perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannak, R.O. Measuring knowledge management performance. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 2009, 35, 242–253. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, A. Knowledge management and organizational performance—Literature review. In Management Challenges in a Network Economy, Proceedings of the MakeLearn and TIIM International Conference 2017, Lublin, Poland, 17–19 May 2017; To Know Press: Lublin, Poland, 2017; pp. 433–440. [Google Scholar]

- Rafi, N.; Ahmed, A.; Shafique, I.; Kalyar, M.N. Knowledge management capabilities and organizational agility as liaisons of business performance. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qarioti, M.Q.A. The Impact of Knowledge Management on Organizational Performance: An Empirical Study of Kuwait University. Eurasian J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieba, M.; Bolisani, E.; Scarso, E. Emergent approach to knowledge management by small companies: Multiple case-study research. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ashraf, S.F.; Shahzad, F.; Bashir, I.; Murad, M.; Syed, N.; Riaz, M. Influence of Knowledge Management Practices on Entrepreneurial and Organizational Performance: A Mediated-Moderation Model. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 577106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Efficiency and effectiveness of knowledge management systems in SMEs. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 30, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, H.; Hynek, J.; Xu, J.; Akbar, A.; Jabeen, S. Impact of knowledge management capabilities on new product development performance through mediating role of organizational agility and moderating role of business model innovation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 950054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F.; Lee, G.G. Impact of organizational learning and knowledge management factors on e-business adoption. Manag. Decis. 2005, 43, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharakhani, D.; Mousakhani, M. Knowledge management capabilities and SMEs’ organizational performance. J. Chin. Entrep. 2012, 4, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byukusenge, E.; Munene, J.C. Knowledge management and business performance: Does innovation matter? In Cogent Business & Management; Ratajczak-Mrozek, M., Ed.; Cogent: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; Volume 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.P.; Ou Yang, Y.C.; Power, D.J. Effects of Knowledge Management Capabilities on Perceived Performance: An Empirical Examination. In Decision Support for Global Enterprises; Annals of Information Systems; Kulkarni, U., Power, D.J., Sharda, R., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byukusenge, E.; Munene, J.; Orobia, L. Knowledge Management and Business Performance: Mediating Effect of Innovation. J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 2016, 4, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lowik, S.; Van Rossum, D.; Kraaijenbrink, J.; Groen, A. Strong ties as sources of new knowledge: How small firms innovate through bridging capabilities. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2012, 50, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, J.; Sharma, K.; Bobek, S. Key factors for knowledge management: Pilot study in IT SMEs. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2016, 5, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampaoli, D.; Sgrò, F.; Ciambotti, M.; Bontis, N. Integrating knowledge management with intellectual capital to drive strategy: A focus on Italian SMEs. Vine J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2021, 54, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Using knowledge management systems: A taxonomy of SME strategies. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Knowledge management systems: The hallmark of SMEs. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2017, 15, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.T.S. A literature review on knowledge management in organizations. Res. Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Foli, S.; Edvardsson, I.R. A systematic literature review on knowledge management in SMEs: Current trends and future directions. Manag. Rev. Q. 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, M.S. Influence of knowledge management on performance in small Manufacturing firms. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Law 2015, 8, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Balcerzyk, R. Knowledge Management in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2020, 3, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzenopoljac, V.; Alasadi, R.; Zaim, H.; Bontis, N. Impact of knowledge management processes on business performance: Evidence from Kuwait. J. Corp. Transform. 2018, 25, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Games, D.; Rendi, R.P. The effects of knowledge management and risk taking on SME financial performance in creative industries in an emerging market: The mediating effect of innovation outcomes. J. Glob. Entrepr. Res. 2019, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, P.Y.; Suasih, N.N.R. The Effect of Knowledge Management on Competitive Advantage and Business Performance: A Study of Silver Craft SMEs. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2020, 8, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnoli, C.; Vedovato, M. The impact of knowledge management and strategyconfiguration coherence on SME performance. J. Manag. Gov. 2014, 18, 615–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, F.; Khalilzadeh, M.; Soleimani, P. Factors Affecting Knowledge Management and Its Effect on Organizational Performance: Mediating the Role of Human Capital. Adv. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmohammadi, C.; Ahmadi, M. The impact of knowledge management practices on organizational performance. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolyasnikov, M.S.; Kelchevskaya, N.R. Knowledge management strategies in companies: Trends and the impact of Industry 4.0. Upravlenets 2020, 11, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, M.Q.; Gardezi, S.B.W. Application of big data analytics and organizational performance: The mediating role of knowledge management practices. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji-fan Ren, S.; Fosso Wamba, S.; Akter, S.; Dubey, R.; Childe, S.J. Modelling quality dynamics, business value and firm performance in a big data analytics environment. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 5011–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wincent, J. Does size matter? A study of firm behavior and outcomes in strategic SME networks. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2005, 12, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Nicolás, C.; Meroño-Cerdán, Á.L. Strategic knowledge management, innovation and performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson-Thomas, C. The knowledge entrepreneurship challenge: Moving on from knowledge sharing to knowledge creation and exploitation. Learn Organ. 2004, 11, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zack, M.; McKeen, J.; Singh, S. Knowledge management and organizational performance: An exploratory analysis. J. Knowl. Manag. 2009, 13, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašula, J.; Vukšić, V.B.; Štemberger, M.I. The impact of knowledge management on organisational performance. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2012, 14, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantje, M.P.; Rambe, P.; Ndofirepi, T.M. Effects of knowledge management on firm competitiveness: The mediation of operational efficiency. South Afr. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 25, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, N. Knowledge sharing, innovation and firm performance. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 8899–8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.H.; Yang, T.Y. Investigating the success of knowledge management: An empirical study of small and medium-sized enterprises. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2016, 21, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, G.V.; Castillo, A.E.; Manotas, E.N.; Arevalo, O. Analysis of the knowledge management in industrial exporting SMEs. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 203, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandru, V.A.; Bolisani, E.; Andrei, A.G.; Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Martínez Martínez, A.; Paiola, M.; Scarso, E.; Vătămănescu, E.-M.; Zieba, M. Knowledge management approaches of small and medium-sized firms: A cluster analysis. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Qurashi, A.; Mujtaba, G.; Waseem, M.A.; Iqbal, Z. Knowledge management: A roadmap for innovation in SMEs’ sector of Azad Jammu Kashmir. J. Glob. Entrepr. Res. 2019, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, R.V.D.; Novas, J.C. Information and Knowledge Management, Intellectual Capital, and Sustainable Growth in Networked Small and Medium Enterprises. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeje, K. Knowledge Management and Performance of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Lessons from Tanzanian Bakeries. Eurasian J. Bus. Manag. Eurasian Publ. 2020, 8, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhn, A.; Aslanyan, S.; Leopoldseder, C.; Priess, P. An evaluation of knowledge management system’s components and its financial and non-financial implications. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2017, 5, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorovic, M.; Petrovic, D.; Mihic, M.; Obradovic, V.; Bushuyev, S. Project success analysis framework: A knowledge-based approach in project management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciolatti, L.; Fearne, A.; Ihua, B.; Yawson, D. Marketing information as a catalyst of SME growth: Empirical evidence of the moderating role of owner-managers’ gender, age and targeting strategy. J. Strateg. Manag. Educ. 2012, 8, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Samir, M. The Impact of Knowledge Management on SMEs Performance in Egypt. Libr. J. 2020, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, M.J.; Aspelund, A.; Eide, A.E.; Wright, L.T. Knowledge integration in international SMEs—The effects on firm innovation and performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1849890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.; Celic, D.J.; Uzelac, Z.; Draskovic, Z. Specific influence of knowledge intensive and capital-intensive organizations on collaborative climate and knowledge sharing in SMEs. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 25, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, E.; Alfiero, S.; Quaglia, R.; Yahiaoui, D. Financial performance and global start-ups: The impact of knowledge management practices. J. Int. Manag. 2022, 28, 100938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbembo, T.; Awodele, O.; Oke, A. A principal component analysis of knowledge management success factors in construction firms in nigeria. J. Constr. Proj. Manag. Innov. 2020, 10, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghimien, D.; Aigbavboa, C.; Gomes, F.; Thwala, W. Barriers to knowledge management in small and medium construction companies in South Africa. In Proceedings of the Creative Construction Conference, Budapest, Hungary, 11 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dahinine, B.; Chouayb, L.; Bensahel, W. Knowledge Management and Firm Performance in Algerian F&B SMEs: The Role of Trust as a Moderating Variable. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albassami, A.M.; Hameed, W.; Naveed, R.; Moshfegyan, M. Does knowledge management expedite SMEs performance through organizational innovation? An empirical evidence from Small And Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs). Pac. Bus. Rev. Inter. 2019, 12, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cicea, C.; Popa, I.; Marinescu, C.; Cătălina Ștefan, S. Determinants of SMEs’ performance: Evidence from European countries. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2019, 32, 1602–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supyuenyong, V.; Islam, N.; Kulkarni, U. Influence of SME characteristics on knowledge management processes: The case study of enterprise resource planning service providers. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2009, 22, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, A.; Ćosić, I. Knowledge management in small and medium-sized enterprises: The case of Serbia. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance (ICEGOV), New Delhi, India, 7–9 March 2017; pp. 451–454. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez de Pablos, P.; Lytras, M.D. Knowledge management in small and medium enterprises. J. Knowl. Manag. 2008, 12, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

| Freq. | % of Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Company size | Small | 248 | 67% |

| Medium | 122 | 33% | |

| Country of origin | Serbia | 247 | 67% |

| EU | 120 | 32% | |

| Rest of world | 3 | 1% | |

| No. of years doing business | 1–5 | 37 | 10% |

| 6–15 | 215 | 59% | |

| 16–25 | 68 | 18% | |

| 26+ | 50 | 13% | |

| Industry | Manufacturing | 220 | 59% |

| Services | 120 | 32% | |

| Combined | 30 | 19% | |

| Annual revenue range | Less than EUR 10 million | 285 | 77% |

| From EUR 10 to 50 million | 71 | 19% | |

| From EUR 50 to 100 million | 14 | 4% | |

| Knowledge Management Factors of Influence | Dimensions | Previously Analyzed in |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge acquisition | People are the carriers and mediums of new knowledge | Wijaya [60] |

| Business consultancy—key driver for business acceleration | Bagnoli [61], Rezaei [62] | |

| Open two-way communication is present | Valmohammadi [63] | |

| Learning by doing—errors and mistakes are tolerated in the organization | Kolvasnikov [64] | |

| Knowledge formation | Existence of data officer and data management team | Shabbir [65] |

| Knowledge formation tools are easy to use and maintain | Ren Ji fan [66] | |

| Line decision makers are devoting a share of their time to KM | Wincent [67], Lopez Nicolas [68] | |

| KM procedures and rules are established and maintained | Coulson [69] | |

| Knowledge application | There exists an assembled critical team of KM experts | Zack [70] |

| Knowledge is used in products/services innovation | Rasula [71], Mantje [72] | |

| Knowledge is accessible to the whole company | Wang [73] | |

| Data literacy ensures that we apply knowledge the right way | Wang [74] | |

| Knowledge warehousing | There exists knowledge governance (data about data) | Pacheco [75] |

| Data dictionary is set up | Alexandru [76], Hussain [77] | |

| Data ownership is established | Jordao [78] | |

| Data lineage in reporting is easy to follow | Kafigi [79] | |

| Knowledge transfer | Sharing of best practices and cocreation | Luhn [80] |

| Knowledge sharing is embedded in each project in the company | Todorovic [81], Cacciolatti [82] | |

| We have standardized procedures for knowledge transfer | Samir [83] | |

| Mentorships are standard practice in the company | Azari [84] |

| Knowledge Management Factor | Test Statistic | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 Knowledge acquisition Key dimension: business consultancy | Factor Load | 0.88 |

| Cronbach alpha | 0.79 | |

| Variance | 0.13 | |

| eigenvalue | 7.54 | |

| Factor 2 Knowledge formation Key dimension: existence of separate data officer and data management team | Factor Load | 0.84 |

| Cronbach alpha | 0.82 | |

| Variance | 0.09 | |

| eigenvalue | 7.25 | |

| Factor 3 Knowledge application Key dimension: assembled critical team of KM experts | Factor Load | 0.87 |

| Cronbach alpha | 0.75 | |

| Variance | 0.11 | |

| eigenvalue | 7.14 | |

| Factor 4 Knowledge warehousing Key dimension: knowledge governance (data about data) | Factor Load | 0.79 |

| Cronbach alpha | 0.73 | |

| Variance | 0.20 | |

| eigenvalue | 8.22 | |

| Factor 5 Knowledge transfer Key dimension: sharing of best practices and cocreation | Factor Load | 0.85 |

| Cronbach alpha | 0.89 | |

| Variance | 0.02 | |

| eigenvalue | 8.56 | |

| Dimension reduction method: principal component analysis | ||

| Examined KM Factor | Coefficient | Std Error | t | Significance (pval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 220 | 0.03 | 31.96 | 0.01 |

| Knowledge acquisition | 0.79 | 0.04 | 1.35 | 0.01 |

| Knowledge formation | 0.81 | 0.01 | 1.56 | 0.01 |

| Knowledge application | 0.84 | 0.01 | 1.88 | 0.01 |

| Knowledge warehousing | 0.77 | 0.01 | 1.93 | 0.01 |

| Knowledge transfer | 0.76 | 0.01 | 1.48 | 0.01 |

| Interaction | Standardized Interaction Strength | Description |

|---|---|---|

| KA and KF | 0.65 | Increased knowledge acquisition enhances the effectiveness of knowledge formation, resulting in more impactful documentation and sharing. |

| KAp and KW | 0.44 | Actively applying knowledge in projects (KAp) is optimized when employees effectively leverage the knowledge repository (KW), fostering a cycle of continuous improvement. |

| KF and KT | 0.76 | A well-organized knowledge base (KF) facilitates more effective knowledge transfer (KT) sessions, ensuring that valuable insights are communicated and applied. |

| KA, KF, and KAp | 0.34 | The combined effect of acquiring, structuring, and applying knowledge creates a powerful synergy, leading to a comprehensive understanding and utilization of knowledge. |

| KW and KT | 0.45 | An efficiently utilized knowledge repository (KW) enhances the impact of knowledge transfer (KT) initiatives, ensuring that shared knowledge is stored and accessible. |

| Levene Test for Equality of Var. | t-Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Examined KM factor | F | Sig. | t | df | Significance (pval) |

| Knowledge acquisition | 9.59 | 0.01 | 1.35 | 370 | 0.001 |

| Knowledge formation | 9.31 | 0.01 | 1.56 | 370 | 0.02 |

| Knowledge application | 7.22 | 0.01 | 1.88 | 370 | 0.000 |

| Knowledge warehousing | 14.55 | 0.02 | 1.93 | 370 | 0.000 |

| Knowledge transfer | 18.65 | 0.01 | 1.48 | 370 | 0.001 |

| Results of This Research | Petrov (2020) [85] | Batisti (2022) [86] | Adegbembo (2020) [87] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of analyzed factors | 20 | 10 | 30 | 34 |

| Number of companies in sample | 370 | 78 | 114 | 86 |

| Measured influence of KM factor on business performance | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Measured influence of KM factor on organization performance | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Contextual factors | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Research approach | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Conceptualization and terminology | Yes | No | No | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rošulj, D.; Petrović, D.Č.; Arsić, S.M. Knowledge Management in Serbian SMEs: Key Factors of Influence on Internal and External Business Performances. Sustainability 2024, 16, 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020797

Rošulj D, Petrović DČ, Arsić SM. Knowledge Management in Serbian SMEs: Key Factors of Influence on Internal and External Business Performances. Sustainability. 2024; 16(2):797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020797

Chicago/Turabian StyleRošulj, Dragana, Dejan Č. Petrović, and Siniša M. Arsić. 2024. "Knowledge Management in Serbian SMEs: Key Factors of Influence on Internal and External Business Performances" Sustainability 16, no. 2: 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020797

APA StyleRošulj, D., Petrović, D. Č., & Arsić, S. M. (2024). Knowledge Management in Serbian SMEs: Key Factors of Influence on Internal and External Business Performances. Sustainability, 16(2), 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020797