Pricing Strategies for O2O Catering Merchants Considering Reference Price Effects and Unconditional Coupons

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Considering the effect of consumers’ reference prices, how can we formulate price strategies for two types of merchants in S-NPICS and S-PICS?

- (2)

- What impact does the magnitude of the consumer reference price effect have on the pricing strategies and maximum profits of merchants and Meituan?

- (3)

- For catering merchants, which strategy can obtain more profits—participating in coupon stacking or not participating in coupon stacking?

- (1)

- Considering the promotion activities of Meituan when studying the price strategies of catering businesses, this study investigates a scientific pricing strategy for catering businesses that adopt different promotion strategies.

- (2)

- It is found that the unconditional coupon has an influence on the pricing strategies of merchants. The unconditional coupon is a unique paid membership system used by Meituan. The optimal additional coupon value for restaurants participating in such promotional activities is also explored.

- (3)

- In the process of studying the pricing of catering businesses, considering the consumer reference price effect, the expansion coefficient of coupons, and other factors, this study analyzes how this effect impacts the pricing strategies and maximum profits of businesses and provides them with decision support from a practical point of view.

- (1)

- The promotion activities of Meituan are considered when studying the price strategies of catering businesses, and scientific pricing strategies for catering merchants adopting different promotion strategies are studied.

- (2)

- It is discussed that how unconditional coupons impact the pricing strategies of merchants. The unconditional coupon, which is a unique paid membership system in the O2O catering platform, is the focus of this study, considering the best superimposed denomination when merchants participate in this type of promotion.

- (3)

- This work introduces the reference price effect of consumers into the decision-making process of catering and coupon pricing strategies, discusses the influence of the reference price effect on the pricing of Meituan’s unconditional coupons, and further explores the influence of the reference price on the profits of merchants and Meituan.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Pricing Strategies of O2O Supply Chain

2.2. Reference Price Effect

2.3. Promotion Strategies

3. Methods and Assumptions

3.1. Methodology

3.1.1. The Marketing Theory of 4Ps

3.1.2. Stackelberg Game

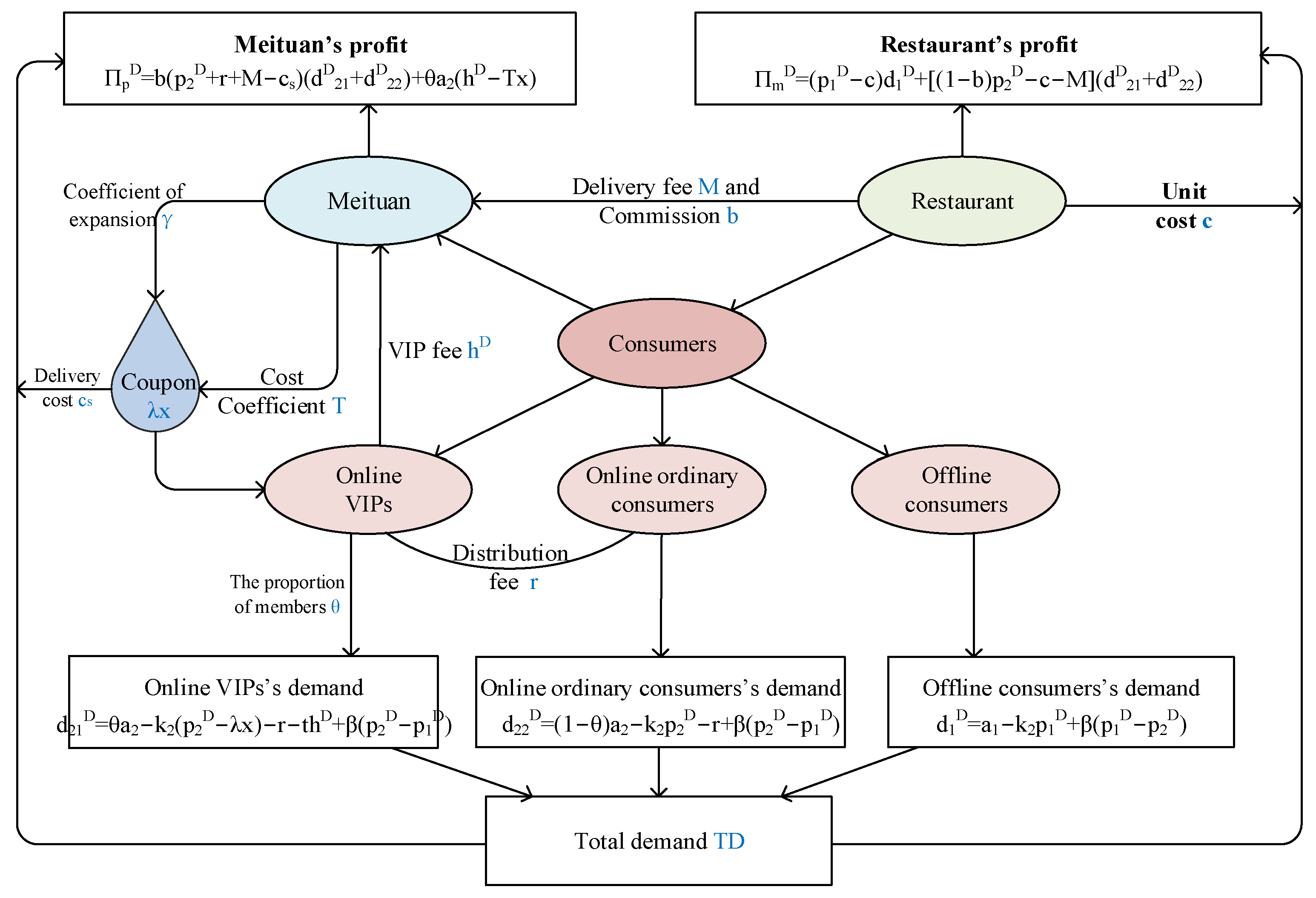

3.2. Problem Description

3.3. Model Assumptions

4. Model Construction and Results

4.1. Catering Merchants Do Not Participate in Coupon Stacking (S-NPICS)

4.2. Catering Merchants Participate in Coupon Stacking (S-PICS)

5. Numerical Analysis

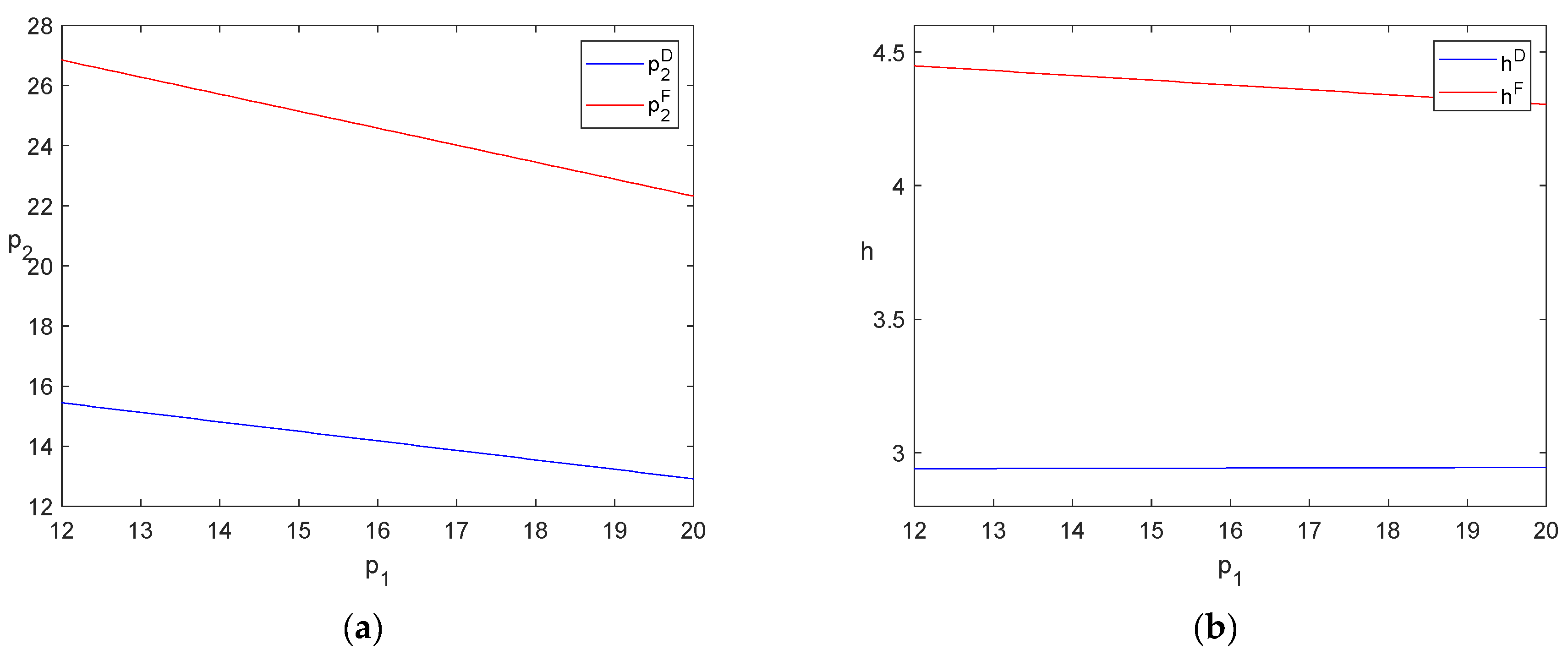

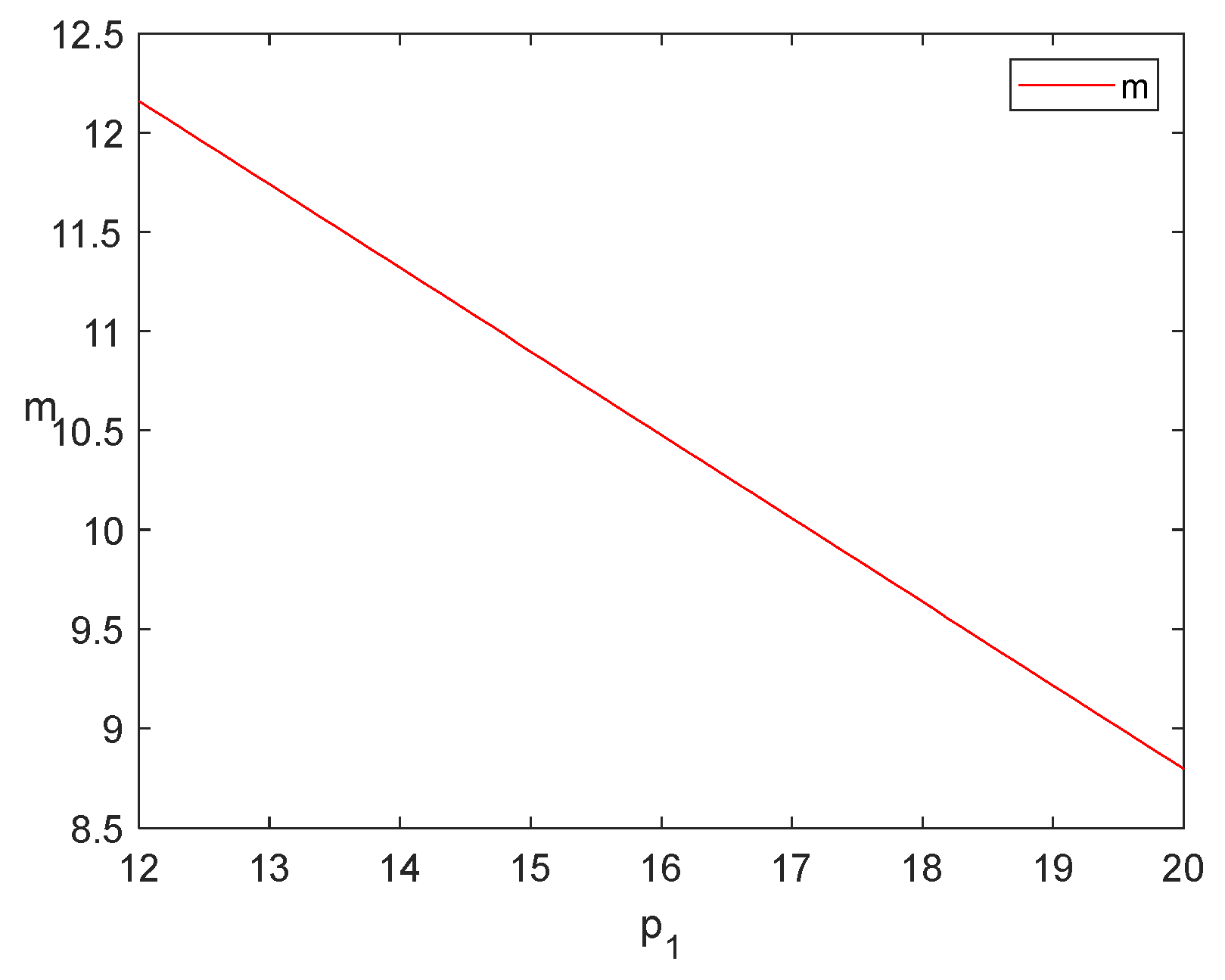

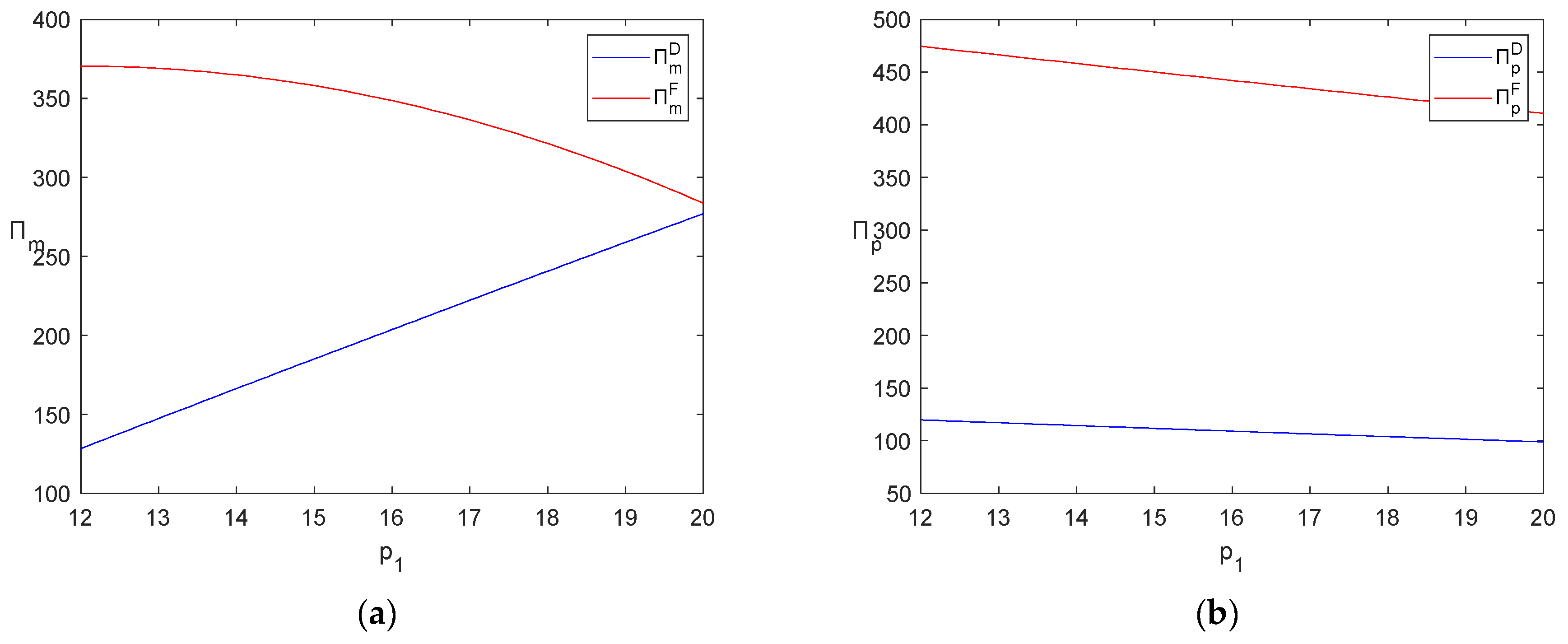

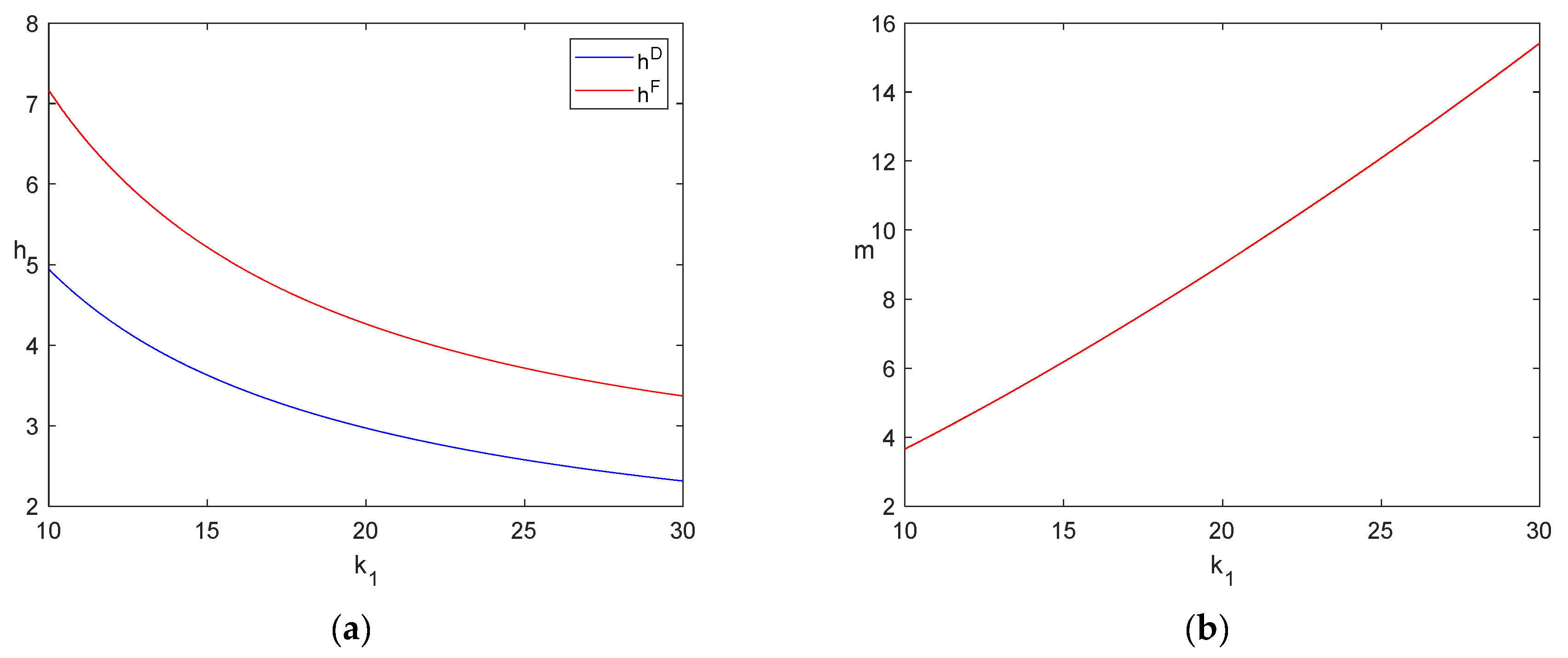

5.1. Impact of Reference Prices of Meals on Decision Variables in Two Scenarios

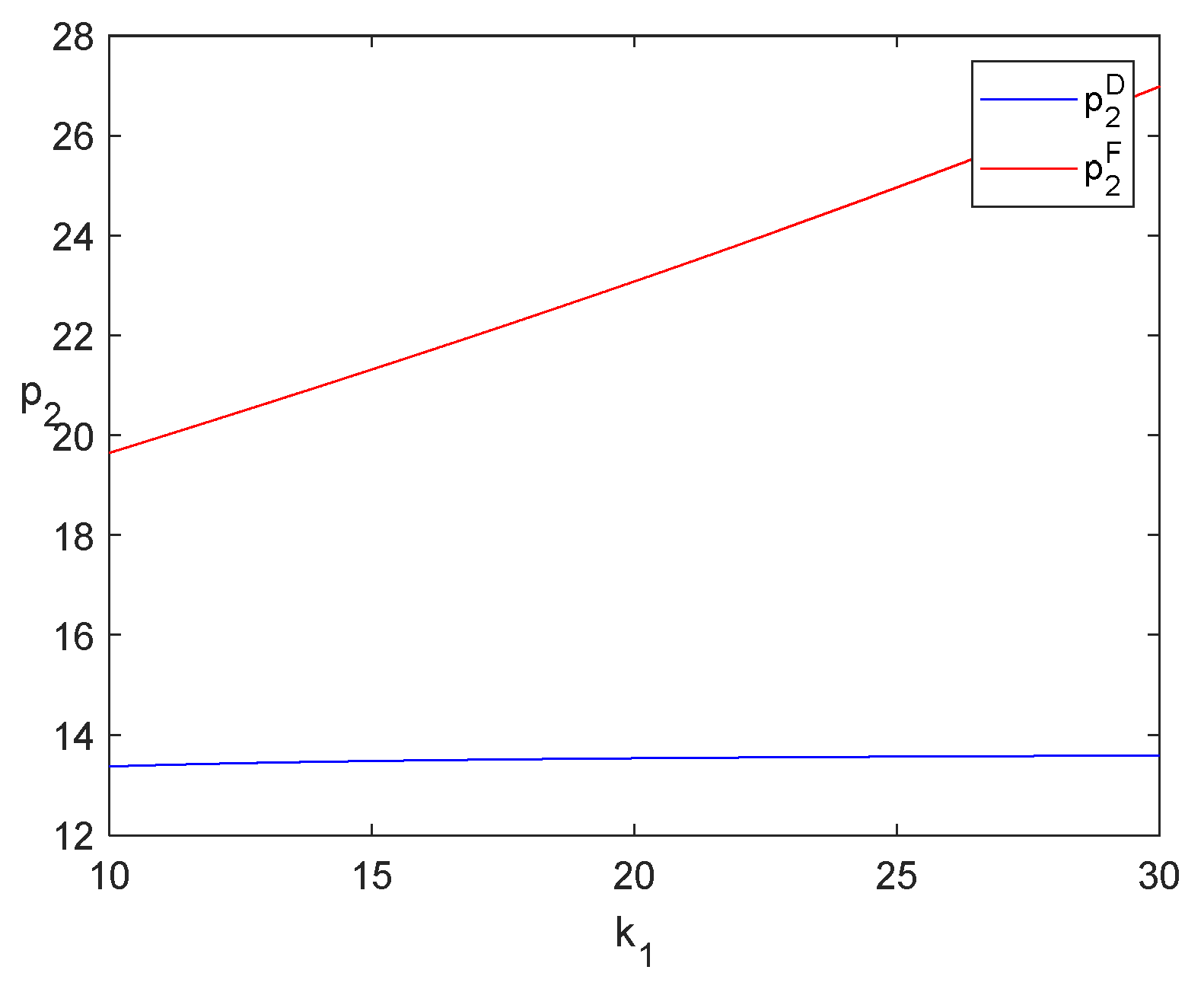

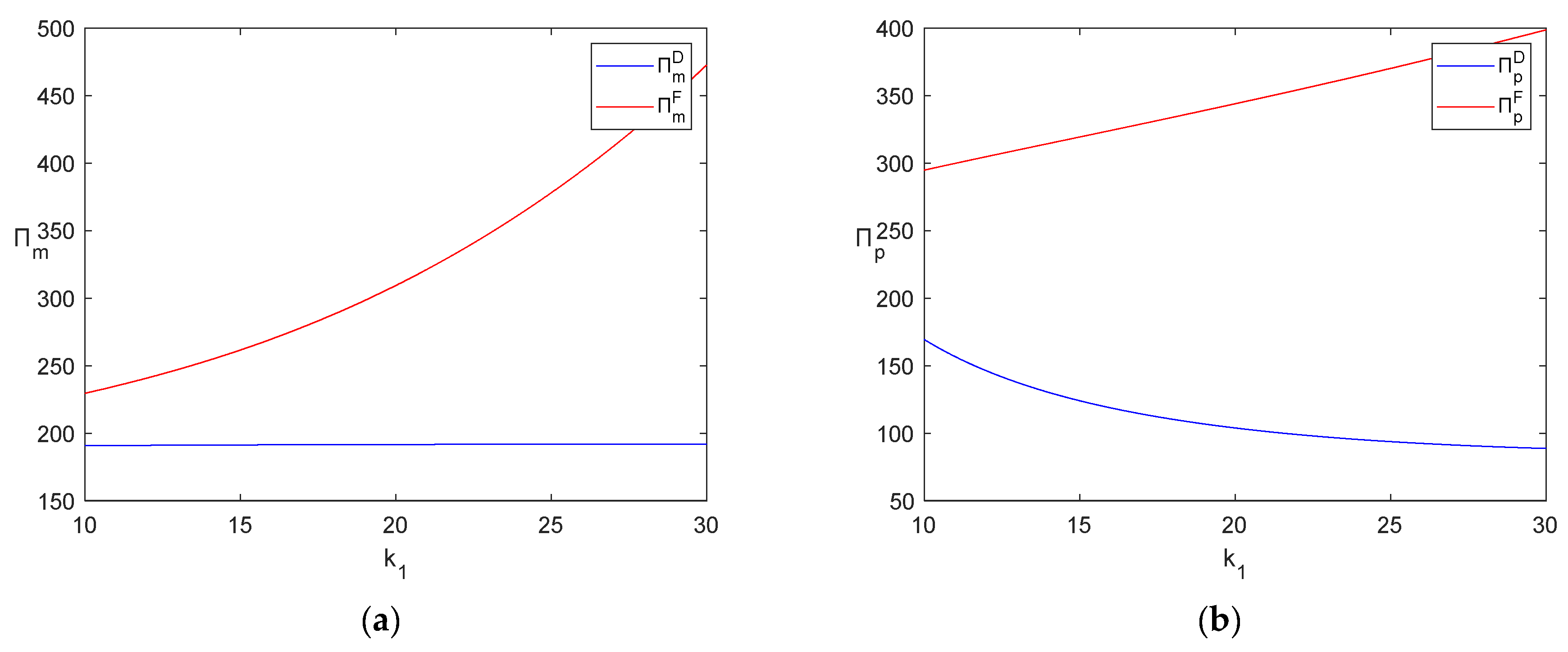

5.2. Impact of Sensitivity Coefficient of Consumer Purchasing Coupons to Coupon Prices on Decision Variables in Two Scenarios

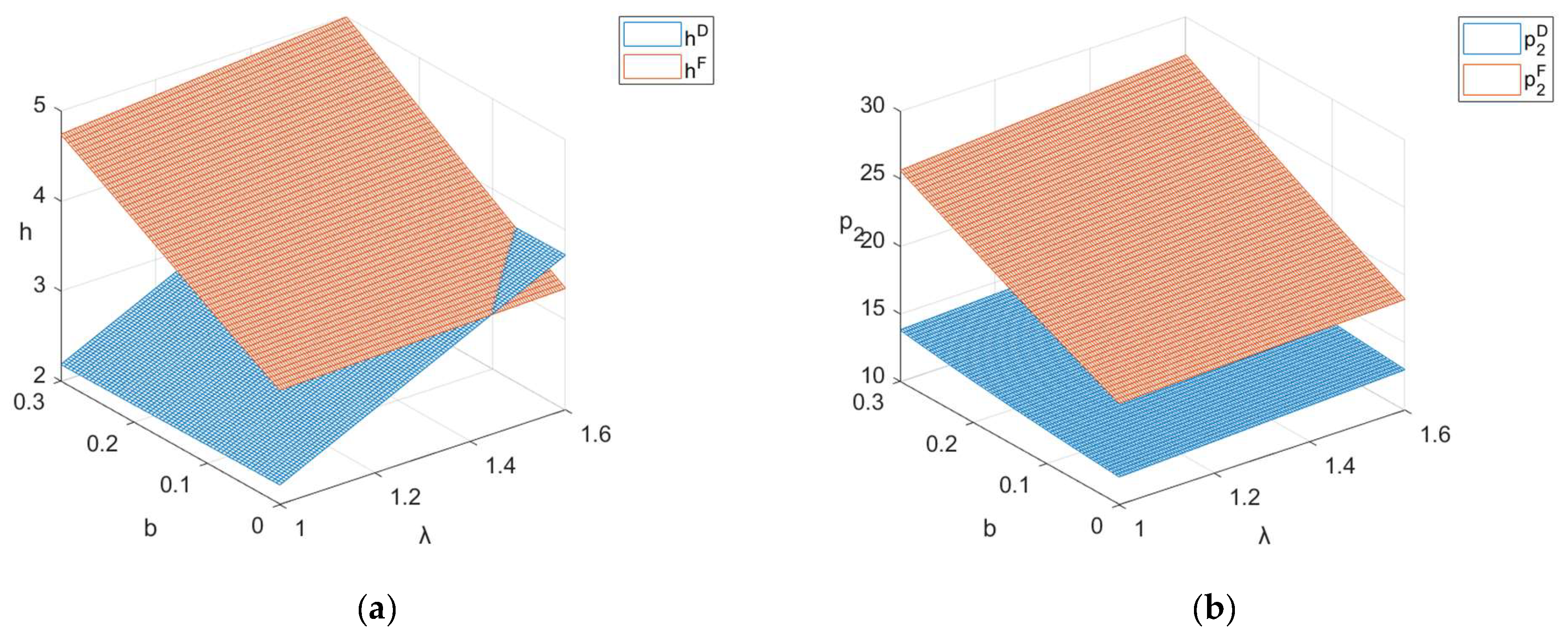

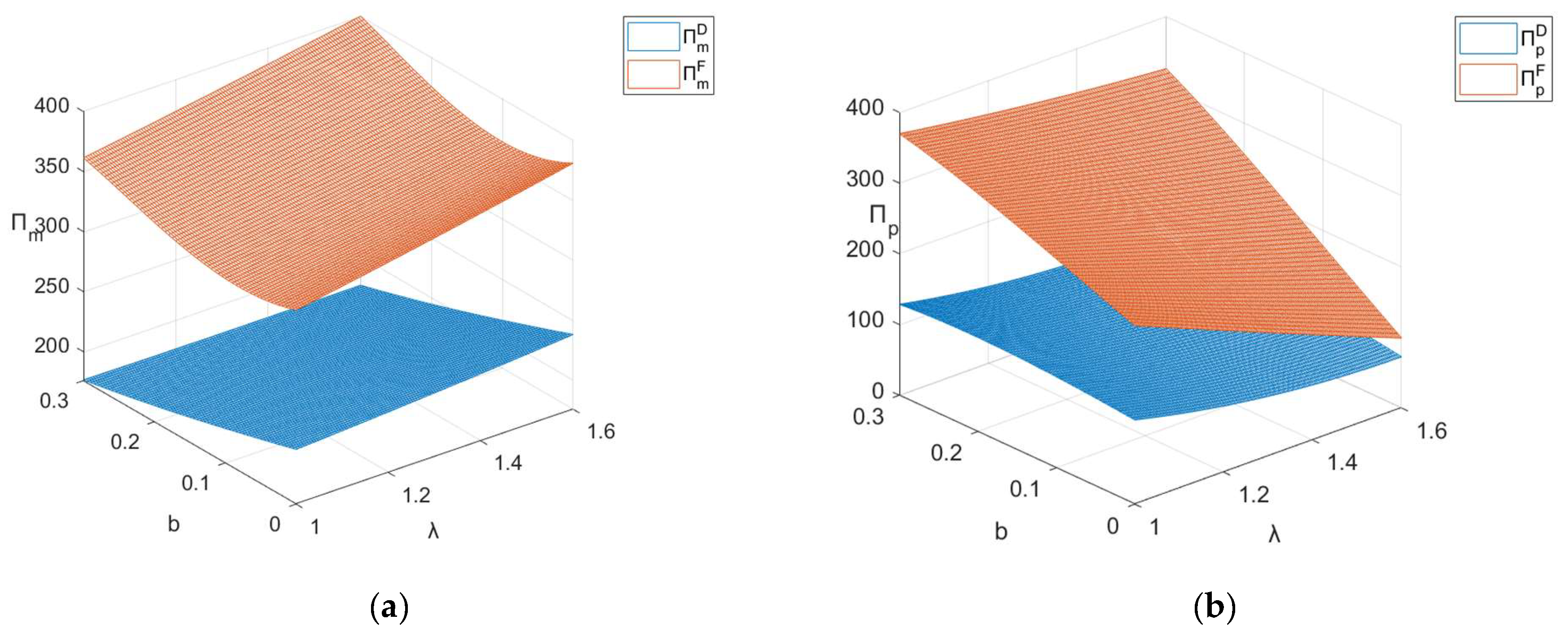

5.3. Impact of Coupon Inflation Coefficient and Meituan’s Commission Rate on Decision Variables in Two Scenarios

6. Discussion and Conclusions

- (1)

- The reference price of consumers will have a great impact on the decision-making of catering businesses. Therefore, when merchants adjust the offline price, the decision variables, such as the online price of the meal and the amount of coupons stacked, should also be changed. In different scenarios, the reference price has various effects on the profit of the merchant. In S-NPICS, the greater the consumer’s reference price, the greater the merchant’s profit. However, in S-PICS, the larger the reference price of consumers, the smaller the profit of merchants.

- (2)

- When formulating pricing strategies, catering merchants and Meituan are supposed to focus on the sensitivity of consumers to coupons when purchasing them. As the sensitivity coefficient increases, it is advisable to lower the price of coupons, increase the amount of coupons stacked, and raise the online price of the meal. In S-PICS, when the inflation coefficient of coupons increases, merchants are expected to raise the coupon price and online price in order to maximize their profits. Merchants should pay close attention to the inflation coefficients of coupons to develop their pricing strategies.

- (3)

- Comparing the S-NPICS and S-PICS scenarios, for catering merchants, participation in coupon stacking allows them to achieve higher profits. Consumers who purchase coupons are often highly sensitive to prices and are particularly concerned about the price of their meals. In this scenario, high-value coupons can offer consumers greater utility, further stimulate consumption, and bring greater profits to merchants.

- (1)

- Merchants should adjust the offline price according to the promotion strategy that they choose. Merchants in the S-NPICS scenario should appropriately increase the offline sales prices of their meals, while merchants in the S-PICS scenario should try to reduce the offline prices of their meals.

- (2)

- Catering businesses should not only carefully formulate their price strategies and promotion strategies, but also explore the use mechanism of Meituan. In addition to some clearly marked data, such as the commission rate, there are some hidden values that can also help businesses to make decisions—for example, the expansion of unconditional coupons. Merchants can dynamically adjust the online prices of meals according to the expansion coefficients of coupons.

- (3)

- For catering businesses whose online channel is the main sales channel, the take-out platform headed by Meituan is their main partner. It is found that the promotion activities launched by Meituan can help businesses to obtain higher profits. Therefore, it is suggested that catering merchants try to participate in the joint promotion activities of Meituan and stack appropriate coupons.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. The Proof of Theorem 1

Appendix A.2. The Proof of Theorem 2

Appendix A.3. The Proof of Proposition 1

Appendix A.4. The Proof of Proposition 2

References

- Ma, S.; He, Y.; Gu, R.; Yeh, C.-H. How to Cooperate in a Three-Tier Food Delivery Service Supply Chain. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J. The Value of Membership Service Sharing in the E-Commerce Marketplace. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 65, 101391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Xu, X.; Yan, N.; Xu, J. Impact of Different Platform Promotions on Online Sales and Conversion Rate: The Role of Business Model and Product Line Length. Decis. Support Syst. 2022, 156, 113746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marketing Rules of Meituan Takeaway Platform. Available online: https://rules-center.meituan.com/rules-detail/788?commonType=7 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Narasimhan, C. A Price Discrimination Theory of Coupons. Mark. Sci. 1984, 3, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Debbarma, J.; Lee, H. Sustainable Management of Online to Offline Delivery Apps for Consumers’ Reuse Intention: Focused on the Meituan Apps. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ju, S.; Huang, H. Can a Restaurant Benefit from Joining an Online Take-Out Platform? Mathematics 2022, 10, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.; Yao, J.; Wang, M. Quality Effort Strategy of O2O Takeout Service Supply Chain under Three Operation Modes. Complexity 2022, 2022, e8177186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Description of Takeaway Membership Rules. Available online: https://i.waimai.meituan.com/node/campaign/rules (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Xu, L.; Meng, Z. The Role of Membership Fees in Online Retail Market Competition. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 67, 102089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Xu, X.; Yan, N.; Chen, Z. Examining the Impact of Information Provision on E-Tailers’ Pricing Strategies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 265, 108990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Han, L.; Xin, G.; Zhang, A.; Ren, H.; Wang, F. Game Theory Based Optimal Pricing Strategy for V2G Participating in Demand Response. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 4673–4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Deng, S.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y. Optimal Promotion Strategies of Online Marketplaces. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 306, 1264–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Qu, Y.; He, G. Pricing Strategy for Green Products Based on Disparities in Energy Consumption. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 69, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Xiao, T. Retailer’s Decoy Strategy versus Consumers’ Reference Price Effect in a Retailer-Stackelberg Supply Chain. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Liu, W.; Tang, O.; Dong, C.; Liang, Y. CSR Investment for a Two-Sided Platform: Network Externality and Risk Aversion. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 307, 694–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-F.; Pang, T.-T.; Kuslina, B.H. The Effect of Price Discrimination on Fairness Perception and Online Hotel Reservation Intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 1320–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Hu, L.; Guo, X.; Yan, X. Online Cooperation Mechanism: Game Analysis between a Restaurant and a Third-Party Website. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2020, 19, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Tang, X.; Sugumaran, V.; Xu, W.; Sun, X. Optimal Rebate Strategy for an Online Retailer with a Cashback Platform: Commission-Driven or Marketing-Based? Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 23, 475–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liu, W.; Shi, J. Research on Price Influencing Factors of Third-Party Payment Platforms: An Empirical Study From China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 829568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Dai, H.; Xiao, Q.; Yan, N. Will Dynamic Pricing Outperform? Theoretical Analysis and Empirical Evidence from O2O on-Demand Food Service Market. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 219, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-C.; Liang, J.-K. Service Pricing Strategy of Food Delivery Platform Operators: A Demand-Supply Interaction Model. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 45, 100904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.-Z.; Mo, Y.-N.; Zhang, Z.-K. A Study on Interplatform Competition Based on a Lotka–Volterra Competition Model Focusing on Network Externality. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 56, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhu, S.; Cao, P.; Wu, J. Analysis of an On-Demand Food Delivery Platform: Participatory Equilibrium and Two-Sided Pricing Strategy. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2024, 75, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Fan, Z.-P.; Gao, G.-X. Choice of O2O Food Delivery Mode: Self-Built Platform or Third-Party Platform? Self-Delivery or Third-Party Delivery? IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 2206–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Fan, Z.-P.; Sun, F. O2O Dual-Channel Sales: Choices of Pricing Policy and Delivery Mode for a Restaurant. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 257, 108766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Du, B.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, J. The Government Subsidy Design Considering the Reference Price Effect in a Green Supply Chain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 22645–22662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shao, L.; Wang, Y. Pricing and Coordination in a Green Supply Chain with a Risk-Averse Manufacturer under the Reference Price Effect. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 1093697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, J.; Qian, Y. Wholesale-Price vs Cost-Sharing Contracts in a Green Supply Chain with Reference Price Effect under Different Power Structures. Kybernetes 2022, 52, 1879–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zha, Y.; Alwan, L.C.; Zhang, L. Dynamic Pricing in the Presence of Reference Price Effect and Consumer Strategic Behaviour. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Herrán, G.; Sigué, S.P. An Integrative Framework of Cooperative Advertising with Reference Price Effects. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Boer, A.V.; Keskin, N.B. Dynamic Pricing with Demand Learning and Reference Effects. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 7112–7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, N.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Q. Optimal Pricing and Inventory Policies with Reference Price Effect and Loss-Averse Customers. Omega 2021, 99, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Wang, Q.; Cao, P.; Wu, J. Pricing Decisions with Reference Price Effect and Risk Preference Customers. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2021, 28, 2081–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famil Alamdar, P.; Seifi, A. Dynamic Pricing of Differentiated Products under Competition with Reference Price Effects Using a Neural Network-Based Approach. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaab, J.; Zaccour, G. Dynamic Pricing in the Presence of Social Externalities and Reference-Price Effect. Omega 2024, 122, 102963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, R.; Chenavaz, R.Y.; Paraschiv, C. Dynamic Pricing, Reference Price, and Price-Quality Relationship. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2023, 146, 104586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri-Harzvili, M.; Hosseini-Motlagh, S.-M. Dynamic Discount Pricing in Online Retail Systems: Effects of Post-Discount Dynamic Forces. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 232, 120864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, D.; Spann, M. Dynamic Pricing and Reference Price Effects. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Z. The Impact of Reference Price Effect on Pricing Decisions. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 36, 1150–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.-X.; Liu, Z. Reference Price Effect of Partially Similar Online Products in the Consideration Stage. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Pu, X.; Wang, Z. Optimal Pricing Strategy for New Products Considering Reference Price Effect in Advance Selling. RAIRO-Oper. Res. 2023, 57, 2045–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Krishnan, R. The Dynamics of Online Consumers’ Response to Price Promotion. Inf. Syst. Res. 2019, 30, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, S. Joint Promotion of Online Retail Based on Promotional Effort under the Shopping Festival Background. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, e6744565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ou, J.; Cao, B. The Roles of Cooperative Advertising and Endogenous Online Price Discount in a Dual-Channel Supply Chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 176, 108980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Hua, G.; Cheng, T.C.E.; Wang, S.; Dong, J.-X. Joint Promotion of Cross-Market Retailers: Models and Analysis. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 3397–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Liu, T.; Mao, Z. How Online Reviews and Coupons Affect Sales and Pricing: An Empirical Study Based on e-Commerce Platform. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Cavusoglu, H.; Raghunathan, S. Value of Membership-based Free Shipping in Online Retailing: Impact of Upstream Pricing Model. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 4131–4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Meng, Z. Dynamic Analysis of Retailers’ Paid Membership Strategy. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, e6412614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Ho, Y.-C.; Tan, X.; Tan, Y. Show Me the Money: The Economic Impact of Membership-Based Free Shipping Programs on E-Tailers. Inf. Syst. Res. 2021, 32, 1115–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chung, S.-H.; Wang, L. Two-Tier Price Membership Mechanism Design Based on User Profiles. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 52, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Sun, X.; Yu, H.; Chung, S.H. Seize the Opportunity of Targeted Marketing Under the Platform Membership Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 1969–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ma, M.; Popkowski Leszczyc, P.T.L.; Zhuang, H. The Influence of Coupon Duration on Consumers’ Redemption Behavior and Brand Profitability. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 281, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, X. Digital Coupon Promotion and Inventory Strategies of Omnichannel Brands. Axioms 2023, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, X.; Yao, G.; Xu, L. Coupon Promotion and Inventory Strategies of a Supplier Considering an E-Commerce Platform’s Omnichannel Coupons. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccarthy, E.J. Basic Marketing: A Managerial Approach; McCarthy, E.J., Ed.; Mcgraw Hill Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- von Stackelberg, H. The Theory of Market Economy. Translated from the German and with an Introduction by A.T. Peacock. London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, W. Hodge & Co, Ltd., 1952, Xxiii p. 328 p., 25/-. In Recherches Économiques de Louvain/Louvain Economic Review; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1952; Volume 18, p. 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Chen, L.; Li, Q.; Zeng, F. Restaurants’ Platform Partnership for Social Promotion and Resilient Revenue: Is Reward-Based Traffic Really Rewardful? Prod. Oper. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Shu, T.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, S. Impacts of Reference Price Effect and Corporate Social Responsibility on the Pricing Strategy of a Remanufacturing Supply Chain. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2023, 19, 7350–7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Zhong, S.; Wang, X.; Ma, S. Price Promotion Considering the Reference Price Effect and Consumer Loyalty: Competition between First-Party and Third-Party Retailers. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 175, 108841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Meng, Z. Optimizing Retailer Ordering Strategies: A Comparative Analysis of Membership and Non-Membership Systems. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Ma, H.-L.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. Hiding or Disclosing? Information Discrimination in Member-Only Discounts. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 171, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SN | Coupon Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | Merchant coupon | Refers to store-specific coupons provided by merchants. |

| C2 | Member’s exclusive coupon | Users, as platform members, will receive coupons without thresholds, which can be inflated. |

| C3 | Daily Shen Quan coupon | As daily God coupons, users can use them in promotion, and their face value can be inflated. |

| C4 | New user’s first order coupon | These coupons are issued to attract new users for their first order only. |

| C5 | Bank special coupon | These coupons can be obtained by binding bank cards as purchasing in Meituan for bundled promotion. |

| C6 | Category exclusive coupon | These include coffee coupons, dessert coupons, fast food coupons and so on. |

| C7 | Allowance union coupon | Users can use these coupons as union members and also can combine them with cashback, discounts, and other coupons if some thresholds are met. |

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

| Scenario where merchants do not participate in coupon stacking (S-NPICS) | |

| Scenario where merchants participate in coupon stacking (S-PICS) | |

| Offline sales price of meals | |

| Online sales price of meals | |

| Price of coupon | |

| Amount of coupons stacked by participating merchants | |

| Cost of meal | |

| Consumer’s reference price effect coefficient | |

| Sensitivity coefficient of consumers to coupon prices when purchasing coupons | |

| Consumer’s sensitivity coefficient to food price | |

| Proportion of members among online consumers | |

| Offline potential consumers of meals | |

| Online potential consumers of meals | |

| Increment in potential consumers brought to merchants by participating in activities | |

| Offline sales of meals | |

| Number of members among online consumers | |

| Number of ordinary users among online consumers | |

| Utility of consumers | |

| Consumers’ evaluation of food | |

| Profits of catering merchants | |

| Profits of Meituan | |

| Distribution and packaging fees borne by consumers | |

| Distribution cost of Meituan | |

| Inflation coefficient of coupons | |

| Proportion of merchants participating in coupon stacking on Meituan | |

| Cost coefficient of coupons borne by Meituan | |

| Distribution and packaging fee borne by merchant | |

| Commission rate paid by catering merchants to Meituan | |

| Sensitivity coefficient of consumers to coupon prices when purchasing meals | |

| x | Basic face value of coupon |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, H.; Xie, J.; Dai, D.; Xie, J. Pricing Strategies for O2O Catering Merchants Considering Reference Price Effects and Unconditional Coupons. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208765

Ma H, Xie J, Dai D, Xie J. Pricing Strategies for O2O Catering Merchants Considering Reference Price Effects and Unconditional Coupons. Sustainability. 2024; 16(20):8765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208765

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Huixian, Jiqing Xie, Debao Dai, and Jiaping Xie. 2024. "Pricing Strategies for O2O Catering Merchants Considering Reference Price Effects and Unconditional Coupons" Sustainability 16, no. 20: 8765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208765