Abstract

The external environment faced by underdeveloped regions is becoming increasingly complex, and the importance of entrepreneurial activities is gradually becoming prominent. To stimulate entrepreneurial vitality in underdeveloped regions, entrepreneurial opportunities are of paramount importance. In the current research on opportunity co-creation and entrepreneurial action, there is often an oversight regarding the liability of newness and the unique characteristics of underdeveloped regions, which has resulted in a lack of specificity in interpreting the underlying mechanisms at play. In this study, based on the perspective of opportunity co-creation, a survey of 330 entrepreneurs is conducted in four underdeveloped regions in China, namely, Hunan, Guizhou, Sichuan, and Chongqing, in an attempt to clarify the mechanism of opportunity co-creation in entrepreneurial action. The results show that opportunity co-creation not only has a direct positive impact on entrepreneurial action but also exerts an indirect positive effect through the mediating effect of opportunity belief. Additionally, regulatory focus plays a positive moderating role. Our study reveals that entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions should be strict with their investors and partners to improve their belief in the chances of entrepreneurial success so as to efficiently co-create opportunities. Meanwhile, governments in underdeveloped regions should pay attention to creating a favorable entrepreneurial environment, actively building facilities that are conducive to entrepreneurial activities, and creating more entrepreneurial and employment opportunities to help entrepreneurial activities be carried out smoothly.

1. Introduction

As the global economy continues to evolve and technology advances at a rapid pace, innovation and entrepreneurship have taken on pivotal roles in propelling social progress and economic growth. Successful entrepreneurial endeavors have the potential to channel resources, including capital, technology, and talent, toward vibrant and promising sectors and projects. This, in turn, revitalizes market dynamics and fosters the emergence of novel economic growth avenues. However, entrepreneurship constitutes a multifaceted and continually evolving process that frequently encounters challenges such as uncertainties in the external environment, resource constraints, and intense competition, requiring entrepreneurs to engage in thoughtful and deliberative decision-making [1]. In recent years, the number of startups in underdeveloped regions has gradually increased, with a significant proportion being small and micro-enterprises, as well as corporate entities, showcasing remarkable entrepreneurial achievements [2]. However, research reports from the Entrepreneurship Evaluation Center indicate that the failure rate of new ventures in China remains stubbornly high, with up to 70% of new ventures experiencing bankruptcy within five years. Compared with developed regions, underdeveloped areas exhibit numerous differences in geography, politics, economics, and society, and they are relatively scarce in resources. Furthermore, they lack effective mechanisms for resource development and utilization. These resources often fail to fully realize their value, resulting in a significantly lower survival rate for new ventures in underdeveloped areas than in developed regions [3]. Consequently, entrepreneurship activities in underdeveloped regions exhibit unique characteristics.

Entrepreneurial opportunities are the core and necessary condition for entrepreneurial activities [4]; therefore, the authors of this paper conduct research from the perspective of entrepreneurial opportunities. There exist two contradictory epistemologies regarding the origins of entrepreneurial opportunities: the “discovery view” [5] and the “construction view” [6]. The “discovery view” holds that opportunities objectively exist in the external environment, while the “construction view” proposes that entrepreneurs create opportunities based on changes in the external environment. In recent years, scholars, both domestically and internationally, have integrated these two perspectives, emphasizing the integration of multiple actors to expand the scope of collaborative opportunity creation [7]. Compared with developed regions, entrepreneurship in underdeveloped regions faces greater challenges, hindered by both internal and external factors [8]. These regions often lack the necessary human, material, and social resources. Entrepreneurs in such settings may not possess sufficient capabilities to generate creative ideas for market creation [9,10], making it difficult for them to identify and exploit opportunities. This underscores the need for entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions to integrate their entrepreneurial agency with the entrepreneurial environment, engaging in interactive processes that collectively shape opportunities.

The current research on entrepreneurial opportunities tends to focus solely on either the entrepreneur’s individual capabilities or the external environment, thereby exaggerating the influence of individual factors and neglecting the fact that entrepreneurial opportunities are often the result of multiple factors interacting concurrently [11]. Hence, we need to delve deeper into the perspective of opportunity co-creation. After reviewing the existing literature on entrepreneurial opportunities and considering the unique characteristics of entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions, this study introduces two stakeholders: investors and partners, and examines entrepreneurial action from the perspective of opportunity co-creation. So, how does opportunity co-creation influence the performance of new ventures? With the support of investors and partners, what are the endogenous motivations that drive entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions to actively engage in entrepreneurial activities? Are there any other critical mediating variables that might exist between the two? Are there any boundary conditions that affect this process?

The concept of co-creation of opportunities underscores the joint utilization and creation of entrepreneurial resources by entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions and their stakeholders, as well as their pivotal role in the entrepreneurial process [10]. Sun and Im [12] posit that the co-creation of opportunities involves a process in which entrepreneurs engage in repeated interactions with multiple stakeholders within the entrepreneurial environment to create both social and economic value, ultimately collaborating to identify and address societal issues. Khanb [13], through research on members of social media enterprises, demonstrated their creative and innovative processes of co-creating opportunities. Deng et al. [14] evidenced that entrepreneurs engage in repeated interactions through practices such as dialogue and research with stakeholders, resulting in the joint discovery and creation of entrepreneurial opportunities. De Silva et al. [15], by examining social enterprises, proposed an understanding of the co-creation of opportunities where businesses, their partners, and policymakers collaborate to create opportunities that address global economic and social issues.

Entrepreneurs have their own personalized understanding and judgment of entrepreneurial opportunities. Only when they perceive the potential value and feasibility of an opportunity, and believe that they can seize and utilize it, will they be motivated to take entrepreneurial action [16]. By engaging in opportunity co-creation, entrepreneurs can strengthen their belief in the success of their venture, which is referred to as opportunity belief. Therefore, this study introduces opportunity belief as a mediating variable. To successfully establish an opportunity belief, entrepreneurs need to possess a positive mindset and approach life and their aspirations with enthusiasm, exploring new possibilities and moving forward in directions that favor success [17]. Consequently, this study introduces a regulatory focus to facilitate entrepreneurs’ thoughts and cognitions.

Through an analysis of the relevant literature on opportunity co-creation, opportunity belief, regulatory focus, and entrepreneurial action, this paper finds that while a significant amount of research has focused on the influencing factors of entrepreneurial action, few studies have conducted in-depth research from the perspective of how new ventures can overcome their liabilities of newness. Opportunity co-creation is a crucial factor for entrepreneurs to achieve success in their ventures. While some scholars have begun to examine its impact on entrepreneurial action, there is still a lack of in-depth analysis of the underlying mechanisms [18]. Similarly, while opportunity belief and regulatory focus have been incorporated into the analysis of entrepreneurial action in existing research, these studies often lack systematicity and integration [19], making it difficult to comprehensively explain the path to successful entrepreneurship. Therefore, how does opportunity co-creation facilitate the initiation of entrepreneurial action? How does opportunity belief play a role in the process of entrepreneurial activities? How does regulatory focus moderate the relationship between opportunity co-creation and opportunity belief? These questions remain to be further analyzed and explored.

However, current research on entrepreneurial activities has predominantly focused on economically developed regions such as the southeastern coastal areas in China, with little attention paid to underdeveloped regions. Consequently, the existing research findings struggle to provide effective guidance for entrepreneurial activities in underdeveloped regions. Therefore, from the perspective of the unique disadvantages faced by underdeveloped regions, studying how local entrepreneurs can efficiently carry out entrepreneurial activities is conducive to economic growth and sustainable development and it is crucial for promoting balanced regional development.

From the perspective of opportunity co-creation, this study surveys 330 entrepreneurs from four underdeveloped regions in China: Hunan, Guizhou, Sichuan, and Chongqing. It constructs a theoretical model that examines how opportunity co-creation influences entrepreneurial actions through opportunity belief and regulatory focus, aiming to clarify the underlying mechanism of this process. This research enriches the theoretical understanding of entrepreneurial activities in underdeveloped regions and provides empirical evidence to support the development of entrepreneurial initiatives in developing countries. Furthermore, we offer scientific theoretical guidance and reference for entrepreneurial practices.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the research hypotheses. Section 3 outlines the research design, including data sources and measurement scales. Section 4 conducts an empirical analysis to validate the research hypotheses. Section 5 discusses the theoretical contributions and practical implications. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the research conclusions and limitations, as well as future research directions.

2. Research Hypotheses

2.1. Opportunity Co-Creation

The concept of co-creation was initially introduced in the context of value co-creation theory, which posits that customers and firms jointly create value. Subsequently, Sun and Im [12] extended this notion of co-creation into the entrepreneurial realm, broadening the relationship to encompass all stakeholders and introducing the concept of opportunity co-creation. This concept suggests that entrepreneurs engage in a series of interactions with stakeholders, such as customers, governments, investors, suppliers, beneficiaries, employees, and donors [12,20], in response to changes in the external environment. Through these interactions, they directly or indirectly integrate and bricolage production factors and resources to jointly create entrepreneurial opportunities. This definition acknowledges both the objective nature of entrepreneurial opportunities and the subjective agency of entrepreneurs and stakeholders while also recognizing the influence of the entrepreneurial environment on these opportunities [21].

Opportunity co-creation represents a pathway through which entrepreneurs and stakeholders engage in mutual selection and collaborative construction. Sun and Im [12], by examining microfinance enterprises that address borrowing needs among the poor, proposed that entrepreneurs can interact with stakeholders to create new resource configurations, thereby developing new opportunities and generating social and economic value. From the perspective of opportunity co-creation, we can discern a process in which enterprises engage in joint selection, participation, dialogue, and construction with various stakeholders. Through this collaborative process, entrepreneurs and their stakeholders are able to derive benefits from opportunity co-creation, ultimately contributing to the creation of new value for the enterprise [13,14,15].

The success of entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions in carrying out entrepreneurial activities is inseparable from stakeholders, and different stakeholders can provide varying degrees of assistance. Compared with entrepreneurs in developed regions, poor entrepreneurs face greater challenges, as their inadequate knowledge can hinder the generation of creative ideas to create markets [10]. Moreover, entrepreneurship is constrained by psychological, social, organizational, and institutional environments, and entrepreneurs often struggle to address these constraints alone, necessitating the support of other stakeholders. Meanwhile, entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions typically confront issues such as rapidly changing external environments, information asymmetry, and market failures stemming from a lack of material and social resources. Therefore, engaging in opportunity co-creation with stakeholders is particularly crucial in underdeveloped regions [22]. During the mutual selection process between entrepreneurs and stakeholders, entrepreneurs can collaborate with stakeholders to develop and utilize necessary resources, including new knowledge, environments, and sufficient trust or power to forge partnerships. This collaboration can lead to the creation of opportunities that benefit the poor and realize social value unity co-creation and partner opportunity co-creation [12]. Investors can provide corresponding material, human, and social resources, while partner opportunity co-creation involves understanding new customer needs, establishing social networks, and jointly creating opportunities.

2.2. Opportunity Co-Creation and Entrepreneurial Action

Entrepreneurial action refers to a comprehensive and integrated set of activities undertaken by individuals in the pursuit of identifying, discovering, and evaluating entrepreneurial opportunities [4]. This process is characterized by three key attributes: firstly, it is an individual-level behavior exhibited by entrepreneurs; secondly, it encompasses a series of processes that involve the acquisition of resources, access to information, and the learning of entrepreneurial knowledge, among others; and, thirdly, it is a multi-faceted phenomenon that spans multiple levels. The current literature has identified several factors that influence entrepreneurial action, including the individual characteristics of entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial intentions, entrepreneurial opportunities, entrepreneurial learning, and the entrepreneurial environment. However, there is a notable gap in existing research, as it has yet to explore the relationship between opportunity co-creation and entrepreneurial action. The black box between these two constructs and their specific mechanisms of interaction remains largely unexamined and warrants further investigation.

For entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions, the inherent geographical environment poses numerous challenges and obstacles, including information asymmetry, a lack of access to crucial market information, scarce resources in their localities, insufficient talent and technical knowledge, and unsupported institutional frameworks [3]. Furthermore, many entrepreneurs in these regions may not have received formal education, resulting in incomplete knowledge systems [23], which can hinder their ability to discover, recognize, and construct entrepreneurial opportunities [10]. As such, the growth and development of startups do not solely rely on a single “dominant” force but rather necessitate the collaborative engagement of multiple stakeholders to facilitate communication and cooperation among different entities. Therefore, it is vital for these entrepreneurs to establish broad partnerships with stakeholders, including investors and collaborators, and to secure their ongoing and essential support.

The recognition and development of entrepreneurial opportunities by investors in underdeveloped regions are of paramount importance. Entrepreneurial opportunities emerge through dynamic interactions among multiple stakeholders, influenced by their diverse experiences. Investors, with their innate vigilance and perception of entrepreneurial opportunities, can assist startups in underdeveloped regions by providing access to critical resources, such as capital, market information, and policy support, thereby mitigating the constraints imposed by internal resource deficiencies [24]. They enable startups to secure the necessary financial, human, material, and social network resources. Consequently, the co-creation of opportunities between entrepreneurs and investors leverages the investors’ knowledge, experience, and expertise to offer advice and consultation for the identification and development of business opportunities. This collaboration provides resource allocation and social network support, facilitating the initiation and execution of entrepreneurial activities.

Opportunity co-creation between entrepreneurs and partners in underdeveloped regions provides a communication and consultation platform for startups and their collaborators. Through interactions with entrepreneurs, partners can gain insights into their entrepreneurial ideas, goals, current challenges, and resource requirements. This not only enables both parties to more accurately define existing customer needs but also potentially uncovers latent customer demands [18]. On the one hand, clarifying existing needs facilitates the improvement and optimization of products and services, ultimately leading to increased revenue. On the other hand, the identification of latent demands signifies new business opportunities, offering a fresh source of growth for startups. Collaboratively discovering and creating entrepreneurial opportunities through co-creation not only aids in the implementation of entrepreneurial endeavors but also strengthens the entrepreneurial team, ensuring steady progress in entrepreneurial activities [18]. Opportunity co-creation between entrepreneurs and partners enables the identification of customers’ legitimate needs and value propositions. With the assistance of partners, entrepreneurs gain access to knowledge, skills, and relational networks, which provide advice, resource allocation, and network support for the recognition and development of entrepreneurial opportunities. This collaboration leads to the joint creation of entrepreneurial opportunities, further fostering entrepreneurial activities and facilitating the establishment of viable profit models. Ultimately, it enables the realization of economic and social value creation [25]. Based on the above analysis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a.

Engaging in opportunity co-creation with investors has a positive impact on entrepreneurial actions.

H1b.

Collaborating in opportunity co-creation with partners has a positive influence on entrepreneurial actions.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Opportunity Beliefs

Opportunity beliefs refer to the individual beliefs formed by entrepreneurs after they overcome their lack of knowledge of opportunity information in their environment. These beliefs represent the entrepreneur’s vision for the future [26]. Drawing upon entrepreneurship action theory and the theory of planned behavior, opportunity beliefs can be divided into two dimensions: the perceived fit between a specific offering and a target market and the perceived overall feasibility of the opportunity [27]. As research progresses, opportunity beliefs can also be categorized into first-person and third-person perspectives [28]. First-person opportunity beliefs are those formed after overcoming a lack of knowledge, requiring imagination and creativity from entrepreneurs. In contrast, third-person opportunity beliefs are those formed through a rigorous analysis [29]. It is only when first-person and third-person opportunity beliefs align that entrepreneurial action can truly commence.

Entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions engaging in opportunity co-creation with investors can facilitate the development of opportunity beliefs. Underdeveloped regions often suffer from a scarcity of human, financial, and material resources. Investors, however, can provide vital resources, such as talent, knowledge, technological equipment, and funding. With their unique insights and well-developed social networks, investors can effectively acquire and integrate resources, assisting entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions to identify and seize entrepreneurial opportunities. This integration and utilization of resources can subsequently translate into competitive advantages for enterprises [30]. The co-creation process between entrepreneurs and investors fosters the emergence of new markets and the transfer of novel resources, technologies, and knowledge [18]. After acquiring additional resources, technologies, and knowledge, entrepreneurs can broaden their social horizons, expand their social networks, and enhance their social interactions. Through these improved social connections, entrepreneurs gradually discover their social value and recognize their relative resource advantages within society. This process enables them to make an objective assessment of the external environment and the feasibility of opportunities [27]. By overcoming their lack of knowledge of the environment and validating the feasibility of opportunities, entrepreneurs ascribe meaning to these opportunities in their minds, thereby fostering the emergence of opportunity beliefs. Ultimately, equipped with this mindset, entrepreneurs are poised to seize entrepreneurial opportunities at opportune moments, navigating a largely predictable entrepreneurial trajectory within their surrounding entrepreneurial environment.

Collaborating with partners in opportunity co-creation can assist entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions in developing strong opportunity beliefs [31]. Through continuous communication and exchange, entrepreneurs and their partners gain a profound understanding of entrepreneurial needs and aspirations. Consultative services provided by partners reinforce the entrepreneurs’ mindset, helping to alleviate issues related to information asymmetry. This, in turn, reduces the uncertainty and complexity of the external environment, enabling entrepreneurs to overcome a state of ignorance. To a certain extent, such collaboration eliminates entrepreneurs’ doubts about the feasibility and desirability of opportunities, thereby boosting their confidence. This increased confidence empowers entrepreneurs to seize opportunities and it reinforces their belief in the potential of their ventures [32]. More importantly, this process can facilitate entrepreneurs’ transition from unconsciousness to spontaneous awareness of the existence of opportunities [27]. Furthermore, partners can assist entrepreneurs in broadening their horizons and expanding their social networks, enabling them to better grasp their advantages and confirm the presence of opportunities. This, in turn, reinforces entrepreneurs’ belief that pursuing these opportunities will lead to the creation of value, thereby fostering a robust opportunity belief. Based on the above analysis, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H2a.

Engaging in opportunity co-creation with investors has a positive impact on opportunity belief.

H2b.

Collaborating in opportunity co-creation with partners has a positive influence on opportunity belief.

Opportunity belief serves as a prerequisite for entrepreneurial action [4]. This belief instills autonomy, initiative, innovation, competitiveness, and risk-taking abilities in entrepreneurs, eliciting a response to goal-oriented stimuli, which ultimately motivate the initiation of entrepreneurial endeavors [33]. Stakeholders play a pivotal role in assisting impoverished entrepreneurs in acquiring, processing, and integrating resources, enabling them to invest these resources and leverage opportunities to create value. Once entrepreneurs develop an opportunity belief, they overcome their lack of knowledge of the external environment [30], facilitating the execution of entrepreneurial actions. After receiving support and financial backing, entrepreneurs construct rational, emotional, and self-reflective beliefs that echo, “This is my opportunity” [19]. This conviction empowers them to believe in their own success and further engage in entrepreneurial activities. The level of attention that entrepreneurs pay to potential opportunities is contingent upon their knowledge, motivation, past experiences, and future concerns regarding the pursuit of those opportunities. When these prerequisites are met, entrepreneurs are likely to possess a high level of entrepreneurial passion, driving them to complete entrepreneurial activities [26]. Consequently, when impoverished entrepreneurs possess a strong opportunity belief, not only does it reinforce their initiative, enthusiasm, and confidence in overcoming poverty and achieving prosperity through entrepreneurship, but it also empowers them to proactively identify and exploit opportunities, thereby advancing the execution of entrepreneurial endeavors. In summary, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

Opportunity belief positively influences entrepreneurial action.

In summary, when entrepreneurs engage in opportunity co-creation with stakeholders, such as investors and partners, they can gain access to relevant information from external markets, and they can acquire and fully utilize corresponding human, material, and social resources, thereby enhancing their competitive capabilities. This process helps to alleviate entrepreneurial ignorance, bolster their confidence, improve the feasibility of opportunities, assist them in seizing those opportunities, and ultimately facilitate the effective execution of entrepreneurial activities. Based on the above, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a.

When entrepreneurs engage in opportunity co-creation with investors, opportunity belief mediates the relationship between this co-creation and entrepreneurial action.

H4b.

When entrepreneurs engage in opportunity co-creation with partners, opportunity belief mediates the relationship between this co-creation and entrepreneurial action.

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Regulatory Focus

Higgins [34] developed regulatory focus theory as a framework for understanding goal-directed behavior, distinguishing between two distinct regulatory orientations: promotion focus and prevention focus. These orientations shape an individual’s thoughts, cognitions, and behaviors. Specifically, individuals with a promotion focus adopt a positive mindset, embracing life and desires with enthusiasm. This state prioritizes ideals and progress, fostering the exploration of new possibilities and advancing toward potential gains that facilitate goal pursuit [17]. In contrast, those with a prevention focus often exhibit a more cautious and vigilant demeanor, characterized by a conservative mindset. The key terms associated with prevention motivation are “obligation” and “responsibility”, emphasizing self-preservation. Individuals with a prevention focus typically engage in convergent thinking, avoid losses, and guard against threats that inhibit goal pursuit [35]. When an individual’s regulatory focus aligns with salient situational characteristics, both promotion and prevention motivations combine to influence specific behaviors [36]. The antecedents of regulatory focus are diverse and include motivational concerns such as needs, gains and losses, approach, and avoidance. This study focuses on the perspective of promotion focus.

Opportunity co-creation between entrepreneurs and investors can facilitate access to vital information and resources. When guided by a promotion focus, entrepreneurs leverage these resources to identify or develop opportunities that maximize the alignment between their current state and desired outcomes, strategically moving towards their envisioned end-state [37]. Furthermore, this fosters an optimistic belief in the future among entrepreneurs, a strong conviction that “this is an opportunity”. To capitalize on these opportunities, entrepreneurs require financing, specialized labor, and information from external sources. When there is a regulatory fit with potential investors, activating mutual motivations, entrepreneurs are more likely to successfully secure these resources. Regulatory focus can enhance entrepreneurial effectiveness [38], embodying the “desire to act” and emphasizing the subjective willingness of entrepreneurs to exploit opportunities. Entrepreneurs, driven by confidence and enthusiasm, seek to discover or create entrepreneurial opportunities, aiming to achieve organizational growth and development-related goals. This guides them towards pursuing potential gains and further securing competitive advantages. As the perceived benefits of entrepreneurial actions increase, so does the entrepreneurial intention, with those possessing a promotion focus demonstrating stronger intentions, thereby facilitating the establishment of opportunity beliefs.

Promotion focus exerts a direct positive influence on tacit knowledge transfer, fueled by a strong motivation for exploration. In such an environment, entrepreneurs are continually inspired to engage in autonomous learning and search for novel knowledge and technologies. Collaborative opportunity creation between entrepreneurs and their partners can unite those with entrepreneurial initiative, enthusiasm, and confidence in overcoming poverty and achieving prosperity, fostering partnerships with a wider range of collaborators and building multidimensional innovation networks [39]. Entrepreneurs can fully articulate their entrepreneurial aspirations and needs [40], progressing together with the encouragement and support of their partners, actively seeking new methods to solve problems. Through continuous experimentation and adaptation, entrepreneurs drive corporate growth and development, bolstering their belief in the likelihood of entrepreneurial success. By collaborating with entrepreneurs, partner organizations can broaden the horizons of impoverished entrepreneurs through a range of consulting services and training activities. By providing information on market changes, they can help these entrepreneurs shift their focus toward exploring unknown territories. This reinforcement fosters their confidence in overcoming the unknown and encourages them to adopt an optimistic and proactive mindset in developing opportunities. Additionally, under the guidance of a promotion focus, entrepreneurs are assisted in cultivating positive and optimistic beliefs in opportunities. In conclusion, we propose the following hypotheses:

H5a.

When entrepreneurs engage in opportunity co-creation with investors, regulatory focus positively moderates the relationship between opportunity co-creation and opportunity belief.

H5b.

When entrepreneurs engage in opportunity co-creation with partners, regulatory focus positively moderates the relationship between opportunity co-creation and opportunity belief.

2.5. Construction of a Theoretical Model

Based on the above literature review and research hypotheses, the theoretical research model below is proposed. The theoretical model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical research model.

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Collection and Sample Sources

This study distributed 500 questionnaires to entrepreneurs in four underdeveloped regions of China, namely, Hunan, Guizhou, Sichuan, and Chongqing, from April to June 2023. A total of 331 questionnaires were returned, and, after excluding those with missing data or not meeting the requirements, 330 valid questionnaires remained, with an effective response rate of 66%.

Before conducting the formal survey, we conducted a small-scale pre-survey to test the rationality of the questionnaire design and the clarity of the questions. Following the pre-survey, the research team refined each item, ensuring that the questions were non-suggestive, considered the literacy level of the target audience, and avoided technical jargon, making the questions easy to understand and unambiguous. During the formal questionnaire collection process, we adopted an anonymous filling method to ensure that the distribution of the questionnaire covered the selected sample. Overall, the characteristics of the valid samples in this survey are consistent with the patterns of entrepreneurial behavior in underdeveloped regions, further indicating that it can reflect the entrepreneurial situation in these areas. The distribution of the questionnaire and the selection of respondents were reasonable.

In the questionnaire, we have established several criteria for screening entrepreneurs. Firstly, there is a geographical requirement, which specifies that participants must come from the four underdeveloped regions of Hunan, Guizhou, Sichuan, and Chongqing in China. Secondly, entrepreneurs must have investors or partners and engage in specific collaborative creation activities, such as co-developing products or services. Finally, we select businesses that have been operating for a certain period of time (3–5 years) to ensure their stability and representativeness.

Based on the basic characteristics of the sample, in terms of gender, 59.4% of the entrepreneurs are male, while 40.6% are female. In terms of educational background, 27.6% hold a high school diploma, 69.7% hold a bachelor’s degree, and 2.7% hold a master’s degree or higher. Regarding the industries represented, 15.2% are in agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery; 2.1% are in mining; 6.7% are in manufacturing; 7.3% are in construction; 28.8% are in wholesale, retail, and logistics; 12.4% are in accommodation and catering; 5.8% are in information transmission, software, and information technology services; 0.6% are in finance; 3.3% are in education; 7% are in culture, sports, and entertainment; 1.8% are in tourism; and 9% are in other industries. Regarding the number of personnel, 68.8% of the enterprises have 10 or fewer employees, 17% have 10–49 employees, 7.3% have 50–99 employees, 3.95% have 100–499 employees, and 3% have over 500 employees. In terms of asset size, 64.2% of the enterprises have assets under CNY 1 million, 17.9% have assets ranging from CNY 1 million to 4.99 million, 7.6% have assets ranging from CNY 5 million to 9.99 million, 5.2% have assets ranging from CNY 10 million to 49.99 million, 2.4% have assets ranging from CNY 50 million to 100 million, 0.9% have assets ranging from CNY 100 million to 300 million, and 1.8% have assets exceeding CNY 300 million. The sample industries cover a wide range of sectors within the national economy, making it representative and conducive to studying the differences in the impact of industry factors. Additionally, the sample includes enterprises of varying ages, sizes, and ownership types, ensuring the applicability and relevance of the research results to a certain extent.

3.2. Measurement of Variables

The items in this study were derived from well-established scales found in the literature. To better align the survey questionnaire with the current research context, we adjusted the wording accordingly. Apart from the demographic variables and items related to entrepreneurial role models, all other items were measured using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 7, which represents the respondents’ level of agreement with each item from “completely disagree” to “completely agree”.

The measurement scales used for the variables in this study are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The measurement scales of the variables.

Furthermore, we also delved into several control variables in this study. Previous research has highlighted gender differences in entrepreneurial actions, with females and males exhibiting varying levels of initiative. Moreover, the accumulation of entrepreneurial experience leads to a deeper understanding of the entrepreneurial process. Therefore, in constructing our models and hypotheses, we incorporated the entrepreneur’s gender and educational background as control variables. Additionally, the size of a firm can significantly impact its entrepreneurial activities. We controlled for three firm-specific attributes: company size, employee numbers, and assets. These variables allowed us to account for potential confounding factors that may influence our findings. In conclusion, our study meticulously controlled for a total of five variables: gender, educational background, company size, employee numbers, and assets.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Common Method Bias (CMB) Test

The data in this study were collected through a questionnaire survey, and the potential for high correlations among certain variable items due to the surveyor or measurement environment, known as common method bias (CMB), was a concern. To mitigate errors in data collection, we adopted an anonymous survey format and randomly ordered the questions to control for CMB. Furthermore, prior to the data analysis, we employed Harman’s single-factor test in SPSS 26.0 to conduct a principal component factor analysis on all variable items. The results revealed that the cumulative variance contribution rate of all factors before rotation was 75.573%, with the variance contribution rate of the first principal component being 34.769%, which did not exceed 40%. This indicates that the data in this study can adequately reflect the original information and do not suffer from severe CMB issues, thereby justifying further analysis [44].

4.2. Reliability and Validity Testing

In this study, the reliability of the scale was examined using SPSS 26.0, and Cronbach’s α coefficients are presented in Table 2. The results indicate that Cronbach’s α coefficients for investor opportunity co-creation, partner opportunity co-creation, opportunity belief, regulatory focus, and entrepreneurial action were 0.903, 0.808, 0.854, 0.828, and 0.885, respectively, all exceeding 0.8. This suggests that the measurement of each dimension factor exhibits high internal consistency, indicating the excellent reliability of the scale [45].

Table 2.

Results of structural validity testing.

Prior to examining the validity of the scale, this study conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on the sample data using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The results revealed that the KMO value was 0.848, exceeding the threshold of 0.8, indicating that the sample data were suitable for a factor analysis. Furthermore, the significance probability of Bartlett’s test of sphericity, as represented by the approximate chi-square statistic, was 0.000, which is less than the significance level of 0.001. This finding underscores the strong internal correlations among the variables and further validates the suitability of the sample data for factor analysis [45].

The structural validity was examined using AMOS 24.0. We compared the goodness-of-fit indices of the proposed theoretical model with the conventional recommended ranges for these indices. As shown in Table 2, the indices fell within the acceptable ranges, leading to the conclusion that the overall fit and adequacy of the model met the required standards [45].

The convergent validity was assessed using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Composite Reliability (CR) measures, as presented in Table 3. The CR values for investor opportunity co-creation, partner opportunity co-creation, opportunity belief, regulatory focus, and entrepreneurial action were 0.907, 0.812, 0.856, 0.834, and 0.892, respectively, all exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.7. Similarly, the AVE values were 0.766, 0.592, 0.600, 0.628, and 0.676, respectively, all above the recommended threshold of 0.5 [45].

Table 3.

Results of convergent validity testing.

The results of the discriminant validity test are presented in Table 4. In this study, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used to examine whether there were significant discriminant validities among the latent variables. The findings show that the square roots of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each latent variable were all greater than the correlation coefficients between the latent variables. Therefore, the questionnaire employed in this study demonstrates good discriminant validity [45].

Table 4.

Results of discriminant validity testing.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

4.3.1. Direct Effect Testing

Statistical significance tests were conducted using AMOS 24.0 software. As shown in Table 5, Hypotheses H1a, H1b, H2a, H2b, and H3, proposed in this paper, were verified. This indicates that the theoretical model constructed in this study can effectively explain the mechanism of how the co-creation of opportunities influences entrepreneurial actions. Firstly, Hypotheses H1a and H1b were confirmed at the significance levels of 0.001 and 0.05, respectively, indicating that the co-creation of opportunities by investors and partners can significantly positively influence entrepreneurial activities. Secondly, Hypotheses H2a and H2b were also confirmed at the significance levels of 0.001 and 0.05, respectively, suggesting that the co-creation of opportunities by investors and partners can significantly positively impact opportunity beliefs. Lastly, the influence path from opportunity beliefs to entrepreneurial actions was significant at the 0.001 level, providing preliminary validation of Hypothesis H3. This indicates that opportunity beliefs play a significant mediating role in the process from the co-creation of opportunities to entrepreneurial activities.

Table 5.

Direct effect tests.

4.3.2. Mediation Effect Tests

Using SPSS 26.0 software, the mediation effect of opportunity belief is tested through a stepwise regression analysis. The results are presented in Table 6. Model M1 includes only the control variables. Models M2 and M3 build upon Model M1 by incorporating investor opportunity co-creation and partner opportunity co-creation, respectively, to examine their individual effects on entrepreneurial action. Model M5 includes only the control variables. Models M6 and M7 extend Model M5 by incorporating investor opportunity co-creation, partner opportunity co-creation, and opportunity belief to investigate their corresponding impacts on opportunity belief. The results indicate that both investor opportunity co-creation (β = 0.234, p < 0.01) and partner opportunity co-creation (β = 0.498, p < 0.01) have significant positive effects on opportunity belief; thus, Hypotheses H2a and H2b are confirmed.

Table 6.

Mediation effect tests.

Furthermore, Model M4 introduces the mediating variable of opportunity belief on top of Model M1 to examine its influence on entrepreneurial action. The results show that opportunity belief positively affects entrepreneurial action (β = 0.565, p < 0.01), confirming Hypothesis H3. Finally, based on the results of Models M6 and M7, as well as incorporating the findings from Model M4, Models M8 and M9 are derived by examining opportunity belief as a mediating variable. The results of Model M8 indicate that opportunity belief (β = 0.512, p < 0.01) mediates the relationship between investor opportunity co-creation (β = 0.152, p < 0.01) and entrepreneurial action. Similarly, the results of Model M9 show that opportunity belief (β = 0.434, p < 0.01) mediates the relationship between partner opportunity co-creation (β = 0.367, p < 0.01) and entrepreneurial action. Summarizing the findings from Models M8 and M9, it is evident that the positive effects of the two dimensions of opportunity co-creation on entrepreneurial action remain significant, yet their regression coefficients decrease compared with those in Models M2 and M3. This indicates that opportunity belief partially mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial involvement and entrepreneurial action among the disadvantaged, thereby confirming Hypotheses H4a and H4b.

By using the Process plugin of SPSS 26.0, we examine the mediating role of opportunity belief in the relationship between investor opportunity co-creation, partner opportunity co-creation, and entrepreneurial action. The results are presented in Table 7. The 95% confidence interval for the mediating effect of “investor opportunity co-creation → opportunity belief → entrepreneurial action” is [0.069, 0.227], which does not include 0, indicating a significant mediating effect and further support for Hypothesis H4a. Similarly, the 95% confidence interval for the mediating effect of “partner opportunity co-creation → opportunity belief → entrepreneurial action” is [0.045, 0.136], which also excludes 0, suggesting a significant mediating effect and further support for Hypothesis H4b.

Table 7.

Mediation effect path tests.

4.3.3. Moderating Effect Testing

Before examining the moderating effects, we centered the variables related to investor opportunity co-creation, partner opportunity co-creation, regulatory focus, and entrepreneurial action to address the issue of collinearity in the multiple regression equations. In Models M10 and M11, with the control variables held constant, we introduced the variable of regulatory focus to test its relationship with entrepreneurial action and opportunity beliefs, respectively. The results indicate that the relationships were not significant. Models M12 and M13 separately tested the effects of the interaction terms between investor opportunity co-creation and regulatory focus, as well as between partner opportunity co-creation and regulatory focus, on entrepreneurial opportunity beliefs. The results indicate that both the interaction term between investor opportunity co-creation and regulatory focus (β = 0.070, p < 0.01) and the interaction term between partner opportunity co-creation and regulatory focus (β = 0.079, p < 0.01) positively influenced entrepreneurs’ opportunity beliefs. Consequently, Hypotheses H5a and H5b were supported. See Table 8 for details.

Table 8.

Moderating effect tests.

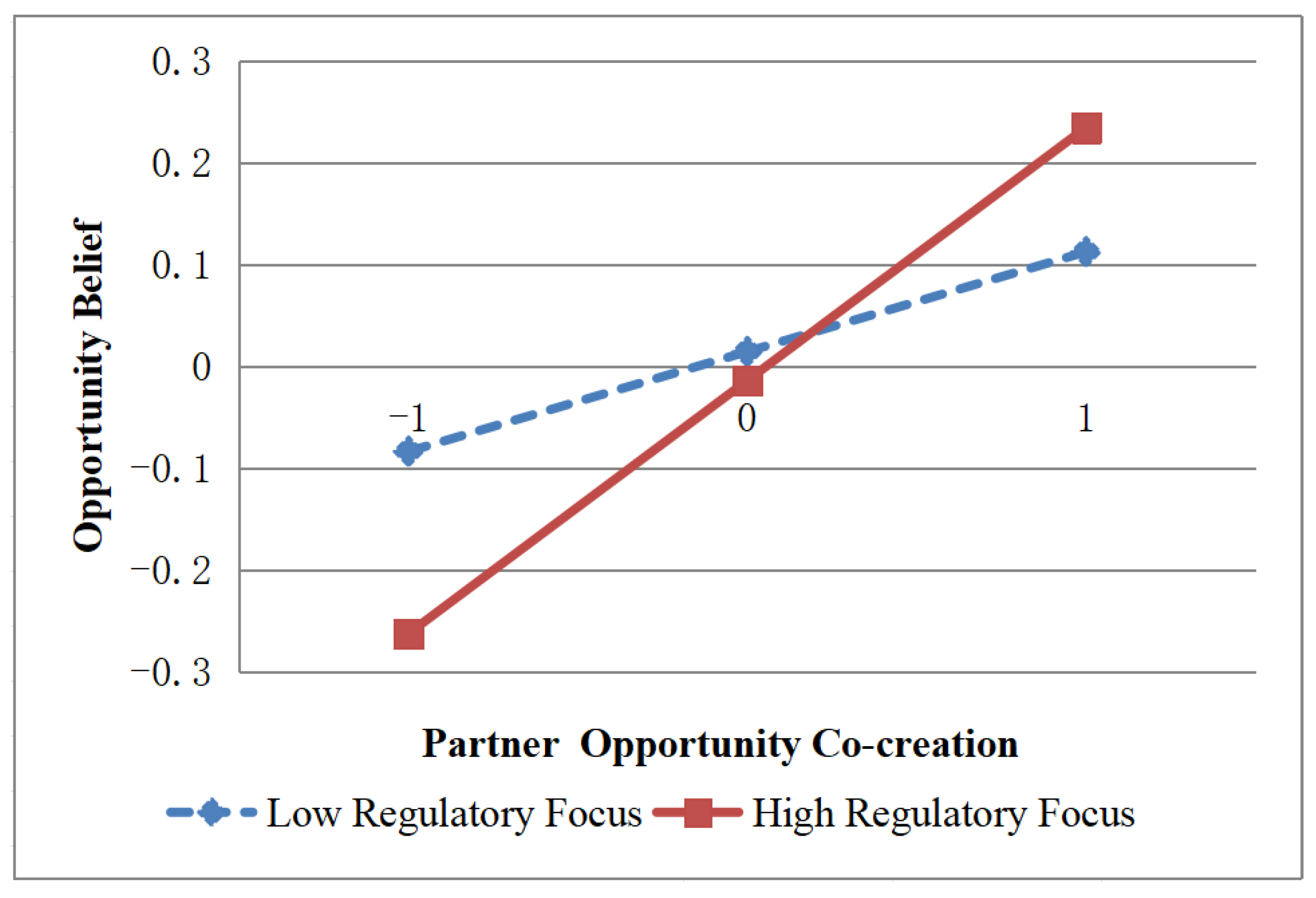

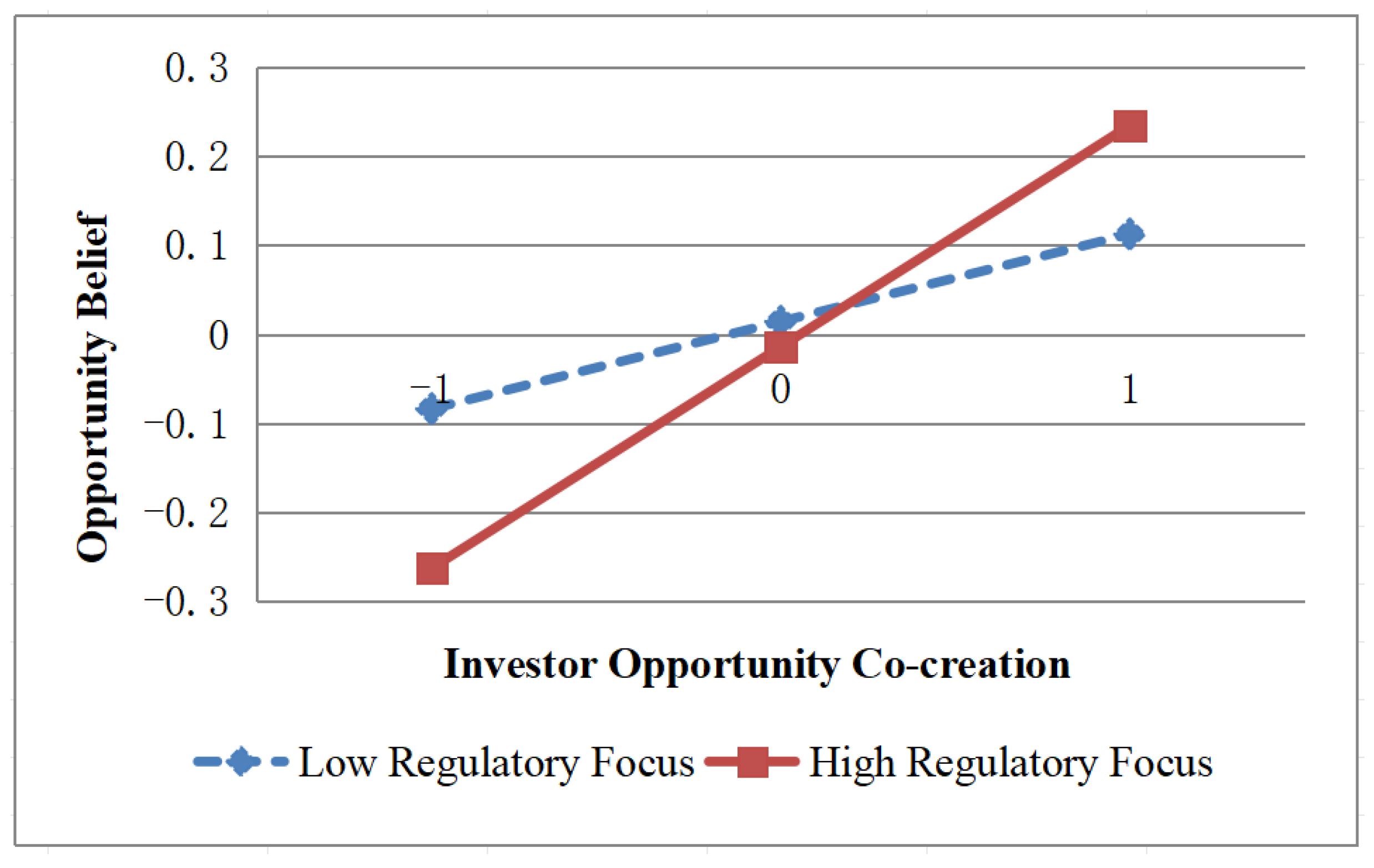

To further analyze how the moderating effects of different paths vary with the values of the moderator, this study utilized the Process 4.1 plugin in SPSS 26.0 to visually demonstrate the moderating role of regulatory focus in the relationship between opportunity co-creation and opportunity beliefs. Specifically, we categorized the moderator regulatory focus into high regulatory focus (M + SD) and low regulatory focus (M − SD), where M represents the mean and SD represents the standard deviation. Based on this, we constructed moderation effect plots for regulatory focus, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. We observed that regulatory focus exerts a positive moderating effect on the relationships between various dimensions of opportunity co-creation and opportunity beliefs. When regulatory focus was at a lower level, the positive impact of each dimension of opportunity co-creation on entrepreneurial action was relatively flat. In contrast, when regulatory focus was higher, the positive relationship between each dimension of opportunity co-creation and entrepreneurial action became steeper, indicating that the higher the regulatory focus, the more significant the positive impact of opportunity co-creation on entrepreneurial action.

Figure 2.

The moderating role of regulatory focus in the relationship between investor opportunity co-creation and opportunity belief.

Figure 3.

The moderating role of regulatory focus in the relationship between partner opportunity co-creation and opportunity belief.

Finally, the moderated mediation effect was tested using the Bootstrap method through the Process plugin in SPSS 26.0. The results are presented in Table 9. In the paths “investor opportunity co-creation → opportunity beliefs → entrepreneurial action” and “partner opportunity co-creation → opportunity beliefs → entrepreneurial action”, the 95% confidence intervals did not include 0, indicating a significant moderating effect of high regulatory focus. However, at low levels of regulatory focus, the 95% confidence intervals included 0, indicating that the moderating effect on the mediation path was not significant.

Table 9.

Moderated mediation analysis.

4.3.4. Robustness Test

To examine the robustness of this study, we performed a regression analysis after conducting 1% and 99% Winsorization treatment on all continuous variables. The results of the robustness test are presented in Table 10. The results show that opportunity co-creation positively influences entrepreneurial action, and opportunity beliefs act as a partial mediator between opportunity co-creation and entrepreneurial action. Furthermore, regulatory focus positively moderates the relationship between opportunity co-creation and opportunity beliefs. The findings of the robustness test are consistent with the previously mentioned results, indicating that the conclusions of this study possess high robustness.

Table 10.

Robustness test.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes four theoretical contributions: Firstly, it effectively supplements the research on entrepreneurship themes. Existing entrepreneurship studies are predominantly focused on developed countries or regions. By selecting four underdeveloped regions in China—Hunan, Guizhou, Sichuan, and Chongqing—as samples, this study fills a gap in the current academic research on entrepreneurial activities in underdeveloped areas. From the perspective of underdeveloped regions, this study delves into the topic of opportunity co-creation, exploring how entrepreneurs engage in co-creation with stakeholders, such as investors and partners, and the subsequent impact on entrepreneurial action. This approach helps broaden the research dimensions of entrepreneurial activities in underdeveloped areas and contributes to the global exploration of new avenues for promoting entrepreneurship.

Secondly, we delve into the intrinsic logic between opportunity co-creation and entrepreneurial action, shedding light on the previously unexplored relationship between the two. Most existing studies focus on the antecedents and consequences of entrepreneurial opportunities or actions, yet few scholars have thoroughly examined the connections and distinctions between them from the perspective of opportunity co-creation [10,12]. This study highlights the significant role of opportunity beliefs in entrepreneurial activities and, through empirical testing, confirms the positive mediating effect of opportunity beliefs on the relationship between opportunity co-creation and entrepreneurial action. Furthermore, we introduce the variable of regulatory focus as a moderator and find that it significantly and positively moderates the path from opportunity co-creation to opportunity belief. This discovery uncovers a novel influence pathway of opportunity co-creation on entrepreneurial action, which holds significant implications for research on the origins of entrepreneurial opportunities and entrepreneurial activities.

Thirdly, it proves that opportunity beliefs have a positive effect on entrepreneurial action. Wood and McKelvie [26] posit that opportunity beliefs serve as a driving force for entrepreneurial action and Kitching and Rouse [46] elaborate that when entrepreneurs possess strong opportunity beliefs, they can effectively alleviate their concerns about uncertainty. This, in turn, shapes their entrepreneurial action pathways. It is noteworthy that opportunity beliefs are not merely related to intentions or decision-making; they are closely related to the actual actions taken by entrepreneurs, especially when these beliefs are aligned closely with the entrepreneurs’ personal resources, capabilities, and motivations [47,48]. Bergmann [49] contrasts different types of entrepreneurial opportunities and argues that in research-driven entrepreneurship, industry experience is crucial in shaping opportunity beliefs, as it helps entrepreneurs accurately assess the commercial value of technological innovations. In contrast, in non-research-driven entrepreneurship, human capital exerts a more pronounced influence on opportunity beliefs, with a greater emphasis on market insights and business model innovations. Shepherd et al. [32] argue that opportunity beliefs drive entrepreneurial action by shaping the perceptions and evaluations of senior managers toward potential opportunities worthy of strategic development. Evidently, this paper reaches a similar conclusion to the aforementioned scholars and corroborates the validity of this perspective within the context of entrepreneurs in underdeveloped regions.

Lastly, this study clarifies the influence of opportunity co-creation on entrepreneurial action, offering potential theoretical guidance for entrepreneurial practices in underdeveloped regions. Entrepreneurs in these regions often lack professional knowledge, skills, and experience; struggle to keep abreast of market changes; and face shortages of human and material resources [3,10,12]. Recognizing these challenges, this study explores how entrepreneurs can overcome difficulties in the entrepreneurial process through opportunity co-creation with investors and partners, providing scientific theoretical guidance for entrepreneurial practices. This not only contributes to the development of entrepreneurial templates for developing countries but also supports the sustainable economic development of underdeveloped regions.

5.2. Practical Implications

Based on the above research findings, we propose corresponding practical implications from the perspectives of entrepreneurs, governments, partners, and investors. Entrepreneurs should delve into and utilize resources to flexibly respond to market changes. Firstly, entrepreneurs should fully understand the characteristics of regional resources and leverage their unique features and advantages to develop products and services with market competitiveness. Secondly, they should maintain constant market vigilance, grasp market trends, strengthen market research, timely understand the evolving needs of consumers, and flexibly adjust product and service strategies. Entrepreneurs need to conduct market research to understand local living habits, consumption preferences, and unmet needs, in order to identify potential market opportunities. They can also utilize internet tools such as e-commerce platforms and social media to sell local products to a wider market, exploring and expanding more market opportunities.

Governments should continuously optimize the entrepreneurial environment to ensure the effective implementation of entrepreneurial activities. Firstly, they should formulate relevant preferential policies to attract more investors and partners to participate in entrepreneurs’ projects. Secondly, they should strengthen the promotion of preferential policies; establish social networking and cooperation platforms for entrepreneurs; and build communication channels among entrepreneurs, investors, and partners to facilitate effective information exchange. Thirdly, they should organize entrepreneurial competitions, salons, and other events to create a strong entrepreneurial atmosphere and stimulate entrepreneurs’ passion for entrepreneurship. The government can provide learning opportunities such as human resource training and continuing education, and strive to improve the policy, investment, and learning environments, thereby attracting more potential and actual entrepreneurs to jointly create opportunities.

Partners should establish long-term cooperative relationships with entrepreneurs to stabilize their social networks. By building long-term and stable partnerships, partners can understand entrepreneurs’ business ideas and goals through communication and collaboration, jointly develop products and services, and expand market share, thereby enhancing their core competitiveness. Furthermore, partners should provide complementary skills and resources to entrepreneurs, jointly driving the development of entrepreneurial projects to achieve maximum value from the collaboration. Entrepreneurs and their partners can use the mindset of the industrial value chain to develop products or services, extend the industrial value chain, and integrate limited resources in underdeveloped areas to strengthen, optimize, and expand existing industries, striving to create more new entrepreneurial and employment opportunities.

Investors should explore investment opportunities and provide a broader range of services. They should delve into the investment potential of underdeveloped regions, particularly focusing on startups or projects with growth potential. By constructing diversified investment portfolios, investors can mitigate overall investment risks. Furthermore, investors can offer more than just financial support; they can also provide services such as strategic planning, market expansion, and talent recruitment to facilitate the growth and development of entrepreneurs. Investors can assist in establishing entrepreneurial incubation platforms or accelerators, providing entrepreneurs with one-stop services such as office space, equipment, and consulting. Entrepreneurs can also establish benefit connection and sharing mechanisms with investors, expanding their participation and leveraging their enthusiasm, initiative, and creativity to create more opportunities.

6. Conclusions

By focusing on the sources of entrepreneurial opportunities, the authors of this paper construct a theoretical model of “opportunity co-creation–opportunity beliefs–entrepreneurial action” and conduct an empirical study with entrepreneurs from four underdeveloped regions in China, namely, Hunan, Guizhou, Sichuan, and Chongqing, from the perspective of opportunity co-creation. The conclusions of this study are as follows:

Opportunity co-creation has a significant positive impact on entrepreneurial action, with its two dimensions of partner opportunity co-creation and investor opportunity co-creation also having significant positive effects on entrepreneurial action. Opportunity co-creation exerts an indirect positive influence through the mediating role of opportunity beliefs. Simultaneously, regulatory focus plays a positive moderating role between opportunity co-creation and opportunity beliefs. The two dimensions of opportunity co-creation—partner opportunity co-creation and investor opportunity co-creation—have significant positive effects on entrepreneurial action and opportunity beliefs, and they also exhibit significant positive interactions with regulatory focus.

There are several limitations in this study that can be addressed for future improvements. Firstly, while this research focuses on entrepreneurs from the underdeveloped regions of Hunan, Guizhou, Sichuan, and Chongqing in China, the generalizability of the findings remains to be strengthened. To enhance the universality and persuasiveness of the findings, future research should consider broadening the scope to include other developing countries worldwide, investigating how the mechanisms of opportunity co-creation operate in these diverse socio-economic environments. Furthermore, opportunity beliefs and regulatory focus alone are insufficient to fully explain the impact of opportunity co-creation on entrepreneurial action. Subsequent research should explore whether there are additional variables that mediate the relationship between opportunity co-creation and entrepreneurial action. Future studies should delve deeper into and validate potential mediating and moderating effects, such as how social capital, institutional environment, and other factors influence the processes of opportunity identification, evaluation, and exploitation, thereby shaping entrepreneurial action decisions. Through multi-pathway and multi-level analyses, we can gain a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic relationship between opportunity co-creation and entrepreneurial action. Lastly, the present study has not fully considered the multidimensional impacts of the individual characteristics of entrepreneurs and their stakeholders. Future research could incorporate more nuanced analyses of individual and group traits, particularly focusing on the unique cultural backgrounds and social structures of underdeveloped regions. By exploring how these traits interact with opportunity co-creation mechanisms, we can gain insights into how they jointly shape entrepreneurial behavior choices. Additionally, by integrating research on entrepreneurship spirit, we can further reveal the underlying motivations behind entrepreneurial actions, providing more precise strategic recommendations for promoting entrepreneurial activities in underdeveloped regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.O. and Z.L.; methodology, S.O. and Z.L.; software, R.L. and S.O.; validation, R.L. and S.O.; formal analysis, K.C. and Z.L.; investigation, S.O. and Z.L.; resources, K.C. and Z.L.; data curation, S.O. and Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.L. and S.O.; writing—review and editing, K.C.; visualization, R.L.; supervision, Z.L.; project administration, S.O.; funding acquisition, S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the following programs. (1) The Scientific Research Project of Hunan Provincial Department of Education (Grant No. 22A0381): Research on the Impact Mechanism of Multiple Network Embedding on the Growth of New Enterprises—Taking the Underdeveloped Areas as an Example. (2) The Scientific Research Project of Teaching Reform in Ordinary Undergraduate Colleges in Hunan Province (20240100934): Research on the Teaching Mode of “Competition Training” Combined with New Liberal Arts Practice Course Based on Innovative Ability.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by Jishou University.

Informed Consent Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct of the American Psychological Association (APA). The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jishou University. The participants provided their written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Guojie Xie from Xiamen University of Technology for providing valuable comments prior to submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that this research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be interpreted as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Daradkeh, M. Navigating the complexity of entrepreneurial ethics: A systematic review and future research agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Winkler, C.; Wang, S.; Chen, H. Regional determinants of poverty alleviation through entrepreneurship in China. Bus. Entrep. Innov. Towar. Poverty Reduct. 2021, 32, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, C.; Bruton, G.D.; Chen, J. Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filser, M.; Tiberius, V.; Kraus, S.; Zeitlhofer, T.; Kailer, N.; Müller, A. Opportunity recognition: Conversational foundations and pathways ahead. Entrep. Res. J. 2023, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Barney, J.B. Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strat. Entrep. J. 2007, 1, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.; Yu, X.; Wu, A.; Chen, S.; Chen, S.; Su, Y. Entrepreneurship and poverty reduction: A case study of Yiwu, China. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumra, R.; Singh, R. Base of the pyramid producers’ constraints: An integrated review and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurik, A.R.; Audretsch, D.B.; Block, J.H.; Burke, A.; Carree, M.A.; Dejardin, M.; Rietveld, C.A.; Sanders, M.; Stephan, U.; Wiklund, J. The impact of entrepreneurship research on other academic fields. Small Bus. Econ. 2024, 62, 727–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, H. Does opportunity co-creation help the poor entrepreneurs? Evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1093120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenitz, L.W.; Iii, G.W.; Shepherd, D.; Nelson, T.; Chandler, G.N.; Zacharakis, A. Entrepreneurship research in emergence: Past trends and future directions. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.L.; Im, J. Cutting microfinance interest rates: An opportunity co–creation perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, V.; Khan, M.S. Monetising blogs: Enterprising behaviour, co-creation of opportunities and social media entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2017, 7, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Li, E.; Yang, Y. Politics, policies and rural poverty alleviation outcomes: Evidence from Lankao County, China. Habitat Int. 2022, 127, 102631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurial co-creation: Societal impact through open innovation. RD Manag. 2019, 49, 318–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppäaho, T.; Mainela, T.; Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. Opportunity beliefs in internationalization: A microhistorical approach. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2023, 54, 1298–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molden, D.C.; Higgins, E.T. Categorization under uncertainty: Resolving vagueness and ambiguity with eager versus vigilant strategies. Soc. Cogn. 2004, 22, 248–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lan, Z.; Ge, J. Research on the impact of opportunity co-creation behavior on the growth of social enterprises-the reg-ulatory role of enterprise resources. Res. Dev. Manag. 2019, 31, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pidduck, R.J.; Clark, D.R.; Lumpkin, G.T. Entrepreneurial mindset: Dispositional beliefs, opportunity beliefs, and entrepreneurial behavior. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 45–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Barney, J.B. Entrepreneurial opportunities and poverty alleviation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P. Entrepreneurial opportunities and the entrepreneurship nexus: A re-conceptualization. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 674–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Si, S.; Yan, H. Reducing poverty through the shared economy: Creating inclusive entrepreneurship around institutional voids in China. Asian Bus. Manag. 2022, 21, 155–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.R.; Obeng, B.A. Enterprise as socially situated in a rural poor fishing community. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 49, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Targeted poverty alleviation and its practices in rural China: A case study of Fuping county, Hebei Province. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Monsen, E.W.; MacKenzie, N.G. Follow the leader or the pack? regulatory focus and academic entrepreneurial intentions. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2017, 34, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.S.; McKelvie, A.; Haynie, J.M. Making it personal: Opportunity individuation and the shaping of opportunity beliefs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, D.A.; Shepherd, D.A.; Lambert, L.S. Measuring opportunity-recognition beliefs: Illustrating and validating an experimental approach. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 114–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Dahlander, L.; Frederiksen, L. Information exposure, opportunity evaluation, and entrepreneurial action: An investi-gation of an online user community. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1348–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gish, J.J.; Wagner, D.T.; Grégoire, D.A.; Barnes, C.M. Sleep and entrepreneurs’ abilities to imagine and form initial beliefs about new venture ideas. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 105943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T.M.; Zenger, T.R. Entrepreneurs as scientists: A pragmatist approach to producing value out of uncertainty. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2023, 48, 379–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, H.; Preller, R.; Breugst, N. Understanding the life cycles of entrepreneurial teams and their ventures: An agenda for future research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 45, 1119–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Mcmullen, J.S.; Ocasio, W. Is that an opportunity? An attention model of top managers’ opportunity beliefs for strategic action. Strat. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 626–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Guan, H.; Xu, W. Entrepreneurial passion psychology- based influencing factors of new venture performance. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 696963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, E.T. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, P.; Jordan, C.H.; Kunda, Z. Motivation by positive or negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, H.; Campbell, J.T.; O’Leary-Kelly, A.M.; Ellstrand, A.E.; Johnson, J.L. The final countdown: Regulatory focus and the phases of CEO retirement. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 58–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Higgins, E. Regulatory focus theory: Implications for the study of emotions at work. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, E.Y.; Fiss, P.C. Framing Controversial actions: Regulatory focus, source credibility, and stock market reaction to poison pill adoption. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1734–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R.; Van Dijk, D. Motivation to lead, motivation to follow: The role of the self-regulatory focus in leadership processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 500–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Haugland, S.A. The role of regulatory focus and trustworthiness in knowledge transfer and leakage in alliances. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 83, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimov, D. Beyond the single-person, single-insight attribution in understanding entrepreneurial opportunities. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 713–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Guan, J. Entrepreneurial ecosystem, entrepreneurial rate and innovation: The moderating role of internet attention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 625–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, D.A.; Corbett, A.C.; McMullen, J.S. The cognitive perspective in entrepreneurship: An agenda for future research. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1443–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xie, G.; Blenkinsopp, J.; Huang, R.; Bin, H. Crowdsourcing for sustainable urban logistics: Exploring the factors influencing crowd workers’ participative behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwedeh, F.; Adelaja, A.A.; Ogbolu, G.; Kitana, A.; Taamneh, A.; Aburayya, A.; A Salloum, S. Entrepreneurial innovation among international students in the UAE: Differential role of entrepreneurial education using SEM analysis. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 2023, 6, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitching, J.; Rouse, J. Opportunity or dead end? Rethinking the study of entrepreneurial action without a concept of opportunity. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2017, 35, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, A.; Khajeheian, D. Social norms and entrepreneurial action: The mediating role of opportunity confidence. Sustainability 2018, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shao, Y. Decide to take entrepreneurial action: Role of entrepreneurial cognitive schema on cognitive process of exploiting entrepreneurial opportunity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, H. The formation of opportunity beliefs among university entrepreneurs: An empirical study of research- and non-research-driven venture ideas. J. Technol. Transf. 2017, 42, 116–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).