Navigating the Digital Landscape: Evaluating the Impacts of Digital IMC on Building and Maintaining Destination Brand Equity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. IMC Digitalization Revolution

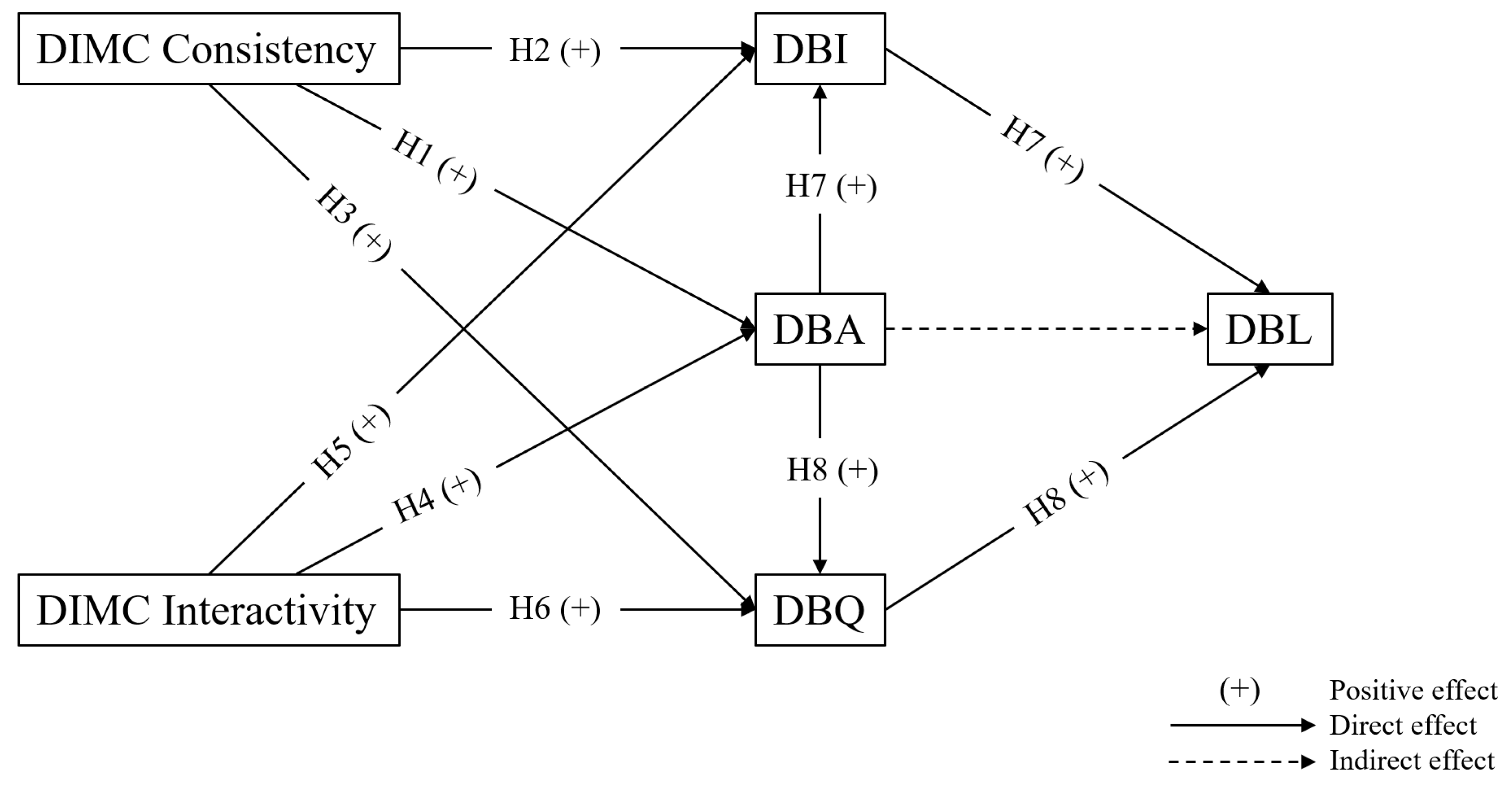

2.2. Perceived Consistency and Interactivity of IMC

2.2.1. Digital IMC Consistency and Destination Brand Equity

2.2.2. Digital IMC Interactivity and Destination Brand Equity

2.3. Consumer-Based Destination Brand Equity (CBDBE)

- Destination Brand Awareness (DBA)

- Destination Brand Image (DBI)

- Perceived Destination Quality (PDQ)

- Destination Brand Loyalty (DBL)

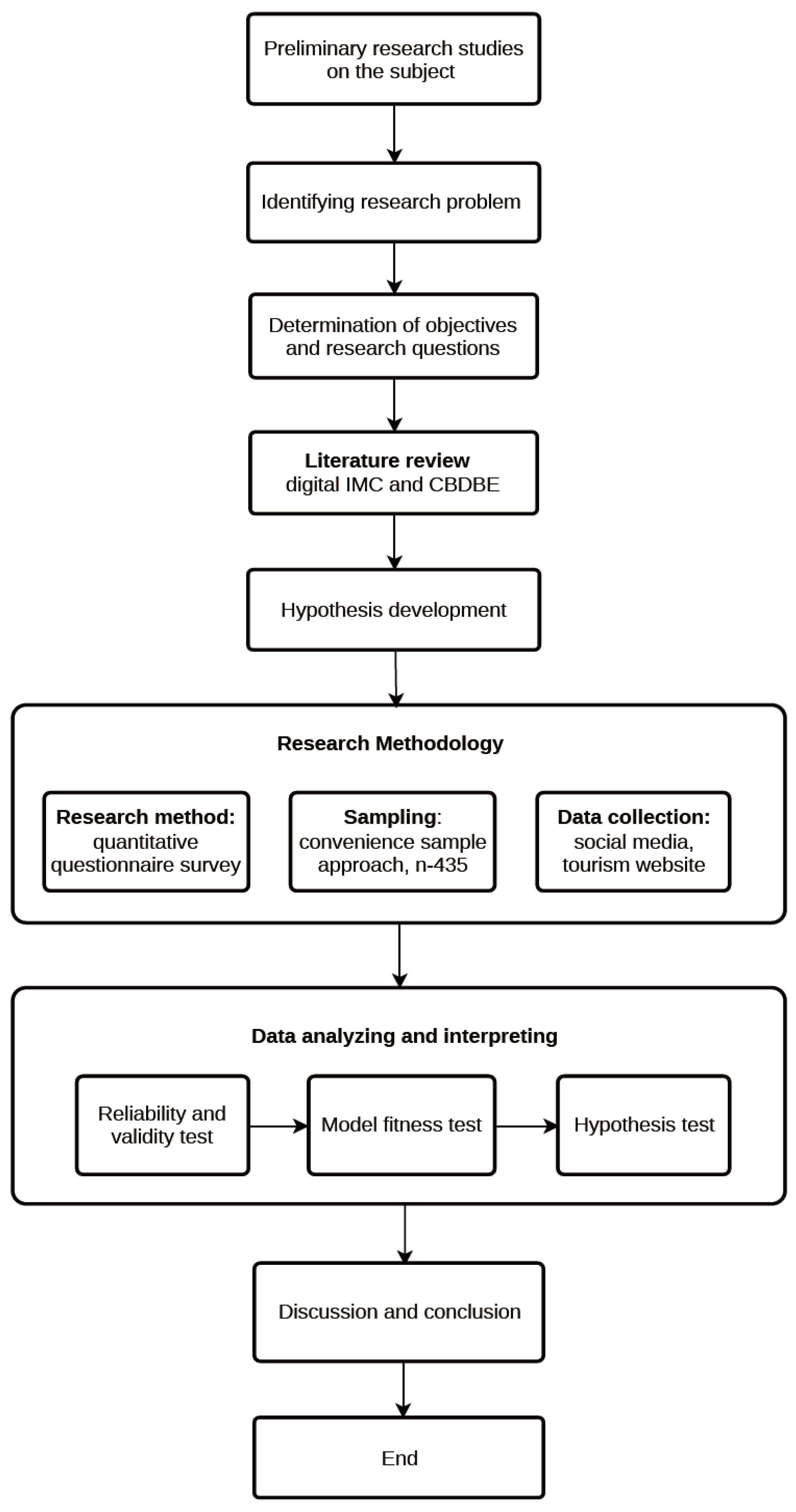

3. Method

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Measurement Scales

4. Results

4.1. Profiles of Respondents

4.2. Measurement Model

4.2.1. Reliability and Convergent Validity

4.2.2. Discriminant Validity

4.3. Model Fitness

4.4. Test of Hypotheses

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, B.P.; Singh, R.K.; Varghese, N.; Singh, V.N. Integrating social media and digital media as new elements of integrated marketing communication for creating brand equity. J. Content Community Commun. 2020, 11, 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen, P.J. Integrated marketing communications. Evolution, current status, future developments. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Peng, M.Y.P.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, G.; Chen, C.C. Expressive brand relationship, brand love and brand loyalty for tablet pcs: Building a sustainable brand. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 231. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, A.S.; Bocci, E.; Dryjanska, L. Social representations of the European capitals and destination e-branding via multi-channel web communication. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Chan, C.S.; Eichelberger, S.; Ma, H.; Pikkemaat, B. The effect of social media on travel planning process by Chinese tourists: The way forward to tourism futures. J. Tour. Futures 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Leveraging digital innovations in tourism marketing: A study of destination promotion strategies. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2024, 12, 08–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Duy, V.U.; TRAN, H.M.N. The Impact Of Electronic Social Media On Asian Tourists’ Destination Decision: A Case Study In The Mekong Delta. Qual. Access Success 2024, 25, 200. [Google Scholar]

- Confetto, M.G.; Conte, F.; Palazzo, M.; Siano, A. Digital destination branding: A framework to define and assess European DMOs practices. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 30, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, I.; Andreu, L.; Curras-Perez, R. Social media communication and destination brand equity. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2022, 13, 650–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teguh, M.; Widjaja, E.; Hartanto, L.; Lukito, J. Implementation of integrated marketing communication at Kampoeng Semarang. In Proceedings of the 2nd Jogjakarta Communication Conference (JCC 2020), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 18–19 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Šerić, M.; Mikulić, J. The impact of integrated marketing communications consistency on destination brand equity in times of uncertainty: The case of Croatia. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadia, S. Influence of IMC on Communication Dissemination. In Integrated Marketing Communications for Public Policy: Perspectives from the World’s Largest Employment Guarantee Program MGNREGA; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, S.U.; Gulzar, R.; Aslam, W. Developing the integrated marketing communication (IMC) through social media (SM): The modern marketing communication approach. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221099936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Itam, U.; Shivaprasad, H.N. Determinants of customer engagement in electronic word of mouth (eWOM) communication. In Insights Innovation and Analytics for Optimal Customer Engagement; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 196–225. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Wu, M.; Liao, J. The impact of destination live streaming on viewers’ travel intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcu, L.; del Barrio-García, S.; Kitchen, P.J.; Tourky, M. The antecedent role of a collaborative vs. a controlling corporate culture on firm-wide integrated marketing communication and brand performance. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 435–443. [Google Scholar]

- Šerić, M. Relationships between social Web, IMC and overall brand equity: An empirical examination from the cross-cultural perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 646–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T.C.; Foroudi, P.; Gupta, S.; Kitchen, P.J.; Foroudi, M.M. Integrating identity, strategy and communications for trust, loyalty and commitment. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 572–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Navarro, A.; Sicilia, M. Revitalising brands through communication messages: The role of brand familiarity. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Dinnie, K.; Kitchen, P.J.; Melewar, T.C.; Foroudi, M.M. IMC antecedents and the consequences of planned brand identity in higher education. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 528–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaftah, D. The effectiveness of electronic integrated marketing communications on customer purchase intention of mobile service providers: The mediating role of customer trust. J. Sustain. Mark. 2020, 1, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juska, J.M. Integrated Marketing Communication: Advertising and Promotion in a Digital World; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fauzi, I. Utilization of Interpersonal Communication in the Context of Digital Marketing: A Review of the Literature and Implications for Business Practices. Join J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 1, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazeli, B. Digital marketing analysis in dental healthcare: The role of digital marketing in promoting dental health in the community. East Asian J. Multidiscip. Res. 2023, 2, 4337–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YÖRÜK, E. Influencer marketing and public relations. J. Bus. Financ. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 6, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, S.; Lee, K.H. Evolution of digital marketing communication: Bibliometric analysis and network visualization from key articles. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrero-Esteban, L.M.; Barrios-Rubio, A. Digital communication in the age of immediacy. Digital 2024, 4, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizaldi, A.; Margareta, F.; Simehate, K.; Hikmah, S.; Albar, C.; Rafdhi, A. Digital marketing as a marketing communication strategy. Int. J. Res. Appl. Technol. 2021, 1, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V.; Grewal, D.; Sunder, S.; Fossen, B.; Peters, K.; Agarwal, A. Digital marketing communication in global marketplaces: A review of extant research, future directions, and potential approaches. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2022, 39, 541–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Keller, K.L. Integrating marketing communications: New findings, new lessons and new ideas. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šerić, M.; Vernuccio, M. The impact of IMC consistency and interactivity on city reputation and consumer brand engagement: The moderating effects of gender. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2127–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, P.J.; Schultz, D.E. IMC: New horizon/false dawn for a marketplace in turmoil? In The Evolution of Integrated Marketing Communications; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, W.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Fan, W. What makes user-generated content more helpful on social media platforms? Insights from creator interactivity perspective. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, P.J.; Tourky, M.E. Integrated Marketing Communications: A Global Brand-Driven Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, K. Strategic orientation, integrated marketing communication, and relational performance in E-commerce brands: Evidence from Japanese consumers’ perception. Bus. Commun. Res. Pract. 2021, 4, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, W.M.; Sutiono, H.T.; Kusmantini, T. Mediation of Brand Equity in The Influence of Integrated Marketing Communication on Purchase Intention of Mie Gacoan Restaurant in Yogyakarta. Manaj. Kewirausahaan 2024, 5, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantachart, S. Integrated marketing communications and market planning: Their implications to brand equity building. J. Promot. Manag. 2006, 11, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šerić, M.; Ozretić-Došen, Đ.; Škare, V. How can perceived consistency in marketing communications influence customer–brand relationship outcomes? Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Guzmán, F.; Kidwell, B. Effective messaging strategies to increase brand love for sociopolitical activist brands. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 151, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-García, J.A.; Frías-Jamilena, D.M.; Del Barrio-García, S.; Rodríguez-Molina, M.A. The effect of message consistency and destination-positioning brand strategy type on consumer-based destination brand equity. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 1447–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šerić, M.; Došen, Đ.O.; Mikulić, J. Antecedents and moderators of positive word of mouth communication among tourist destination residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Molina, M.A.; Frías-Jamilena, D.M.; Del Barrio-García, S.; Castañeda-García, J.A. Destination brand equity-formation: Positioning by tourism type and message consistency. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 12, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, Z. Beyond corporate image: Projecting international reputation management as a new theoretical approach in a transitional country. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2009, 3, 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Majid, K.A. Effect of interactive marketing channels on service customer acquisition. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 35, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaunda, K.; Thuo, J.K.; Kwendo, E. Interactive communication and marketing performance of micro and small enterprises within Nyanza Region, Kenya. Afr. J. Empir. Res. 2023, 4, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M. Performance auditing of integrated marketing communication (IMC) actions and outcomes. J. Advert. 2005, 34, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimusima, P.; Kamukama, N.; Kalibwani, R.; Rwakihembo, J. Relevance of interactive marketing practices for enhancing market performance: The case of soft drink manufacturing enterprises in Kigali City. Am. J. Commun. 2022, 4, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, D.E.; Kitchen, P.J. A response to ‘Theoretical concept or management fashion’. J. Advert. Res. 2000, 40, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Gonçalves, H.M. Consumer decision journey: Mapping with real-time longitudinal online and offline touchpoint data. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, 42, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampela, M.; Lacka, E.; McLean, G. “Just be there” Social media presence, interactivity, and responsiveness, and their impact on B2B relationships. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 1281–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finne, Å.; Grönroos, C. Rethinking marketing communication: From integrated marketing communication to relationship communication. In The Evolution of Integrated Marketing Communications; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Schivinski, B.; Pontes, N.; Czarnecka, B.; Mao, W.; De Vita, J.; Stavropoulos, V. Effects of social media brand-related content on fashion products buying behaviour–a moderated mediation model. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022, 31, 1047–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, D.M. Digital-based SME Innovation Development Strategy: Marketing, Entrepreneurship Insight and Knowledge Management. Golden Ratio Mapp. Idea Lit. Format 2022, 2, 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, P.H. Managing brand equity. Mark. Res. 1989, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zehrer, A.; Smeral, E.; Hallmann, K. Destination competitiveness—A comparison of subjective and objective indicators for winter sports areas. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeyda, M.; George, B. Customer-based brand equity for tourist destinations: A comparison of equities of Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2020, 8, 148–172. [Google Scholar]

- Konecnik, M.; Gartner, W.C. Customer-based brand equity for a destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Boo, S.; Busser, J.; Baloglu, S. A model of customer-based brand equity and its application to multiple destinations. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, H.; Herrero, A.; García de los Salmones, M.D.M. An integrative model of destination brand equity and tourist satisfaction. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1992–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, V.; Alaei, A.R.; Vu, H.Q.; Li, G.; Law, R. Revisiting tourism destination image: A holistic measurement framework using big data. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1287–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, W. Determinants of Hotel Brand Image: A Unified Model of Customer-Based Brand Equity. Int. J. Cust. Relatsh. Mark. Manag. 2022, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.N.; Li, Y.Q.; Liu, C.H.; Ruan, W.Q. Does live performance play a critical role in building destination brand equity—A mixed-method study of “Impression Dahongpao”. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Álvarez, R.; Cambra-Fierro, J.J.; Fuentes-Blasco, M. The interplay between social media communication, brand equity and brand engagement in tourist destinations: An analysis in an emerging economy. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.T.; Nguyen, N.P.; Tran, P.T.K.; Tran, T.N.; Huynh, T.T.P. Brand equity in a tourism destination: A case study of domestic tourists in Hoi An city, Vietnam. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 704–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Fernández, A.C.; Molina, A.; Aranda, E. City branding in European capitals: An analysis from the visitor perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsi, F.; Pike, S.; Gottlieb, U. Consumer-based brand equity (CBBE) in the context of an international stopover destination: Perceptions of Dubai in France and Australia. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, I.; Andreu, L.; Curras-Perez, R. Effects of the intensity of use of social media on brand equity: An empirical study in a tourist destination. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 27, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Lee, T.J. Brand equity of a tourist destination. Sustainability 2018, 10, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kladou, S.; Kehagias, J. Assessing destination brand equity: An integrated approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondonuwu, A.O.; Rangkuti, F. The Influence of Brand Image Brand Awareness and Promotion on Purchase Decisions for Ubiquiti Brand IT Network Devices in Indonesia. Co-Value J. Ekon. Kop. Kewirausahaan 2024, 14, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas, G.B.; Rahmi, S.; Tamsah, H.; Munir, A.R.; Putra, A.H.P.K. Reflective model of brand awareness on repurchase intention and customer satisfaction. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koech, A.K.; Buyle, S.; Macario, R. Airline brand awareness and perceived quality effect on the attitudes towards frequent-flyer programs and airline brand choice—Moderating effect of frequent-flyer programs. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2023, 107, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Apéria, T.; Georgson, M. Strategic Brand Management: A European Perspective; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ekinci, Y.; Japutra, A.; Molinillo, S.; Uysal, M. Extension and validation of a novel destination brand equity model. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 1257–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, M.; Ranjbarian, B.; Fathi, S. Developing a brand equity model for tourism destinations. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2017, 12, 484–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewindaru, D.; Syukri, A.; Maryono, R.A.; Yunus, U. Millennial customer response on social-media marketing effort, brand image, and brand awareness of a conventional bank in Indonesia. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 2022, 6, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Kotsi, F.; Mathmann, F.; Wang, D. Making the right stopover destination choice: The effect of assessment orientation on attitudinal stopover destination loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, Z.; Putri, K.Y.S.; Raza, S.H.; Istiyanto, S.B. Contrariwise obesity through organic food consumption in Malaysia: A signaling theory perspective. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Van Niekerk, M.; Weinland, J.; Celuch, K. Re-conceptualizing customer-based destination brand equity. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 11–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, A.H.; Adnan, M.; Saeed, Z. The Impact of Brand Image on Customer Satisfaction and Brand Loyalty: A Systematic Literature Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parris, D.L.; Guzman, F. Evolving brand boundaries and expectations: Looking back on brand equity, brand loyalty, and brand image research to move forward. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 32, 191–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perception of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Building strong brands in a modern marketing communications environment. J. Mark. Commun. 2009, 15, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaddad, A. Perceived Quality, Brand Image, and Brand Trust as Determinants of Brand Loyalty. J. Res. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dam, S.M.; Dam, T.C. Relationships between Service Quality, Brand Image, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer Loyalty. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 585–593. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Butt, R.S.; Murad, M.; Mirza, F.; Saleh Al-Faryan, M.A. Untying the influence of advertisements on consumers buying behavior and brand loyalty through brand awareness: The moderating role of perceived quality. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 803348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.K.T.; Nguyen, P.D.; Le, A.H.N.; Tran, V.T. Linking self-congruity, perceived quality and satisfaction to brand loyalty in a tourism destination: The moderating role of visit frequency. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kumail, T.; Qeed, M.A.A.; Aburumman, A.; Abbas, S.M.; Sadiq, F. How destination brand equity and destination brand authenticity influence destination visit intention: Evidence from the United Arab Emirates. J. Promot. Manag. 2022, 28, 332–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S. A study of event quality, destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty among sport tourists. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 940–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šerić, M.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E. How can integrated marketing communications and advanced technology influence the creation of customer-based brand equity? Evidence from the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 39, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahaf, T.M.; Fazili, A.I. Does customer-based destination brand equity help customers forgive firm service failure in a tourist ecosystem? An investigation through explanatory sequential mixed-method design. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 31, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Page, S.J. Destination Marketing Organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Bianchi, C.; Kerr, G.; Patti, C. Consumer-based brand equity for Australia as a long-haul tourism destination in an emerging market. Int. Mark. Rev. 2010, 27, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H.E.; Boone, W.J.; Neumann, K. Quantitative research designs and approaches. In Handbook of Research on Science Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 28–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Lau, R.S.; Wang, L.C. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2024, 41, 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, H.K.; Huang, K.C.; Nguyen, H.M. Elements of destination brand equity and destination familiarity regarding travel intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aaker | Keller | Konecnik and Gartner | Boo et al., | San Martin et al., |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 [59] | 1993 [1] | 2007 [58] | 2009 [60] | 2019 [61] |

| Brand Awareness | Salience/Awareness | Destination Awareness | Destination Awareness | Destination Awareness |

| Perceived Quality | Performance | Destination Quality | Destination Quality | Destination Image |

| Brand Association | Imagery | Destination Image | Destination Value | Perceived Quality |

| Brand Loyalty | Judgments | Destination Loyalty | Destination Image | Destination Satisfaction |

| Feelings | Destination Loyalty | Destination Loyalty | ||

| Resonance |

| Author | Brand Equity Dimension |

|---|---|

| Bui et al. [62] | DBA-DPQ, DBA-DBI, DBI-DBL, DPQ-DBL, DBA-DBL |

| Latif [63] | BA-BI |

| Zhang et al. [64] | DBI-DBL, DBA-DBL |

| Huerta-Alvarez et al. [65] | DA-PQ, DI-PQ, PQ-DL |

| Tran et al. [66] | DBA-DBI, DBA-DPQ, DBI-DPQ, DPQ-DBL, DBI-DBL |

| Gómez et al. [67] | BA, BI, BL, BQ |

| Kotsi et al. [68] | DBA, DBI, DBQ, DBV |

| Stojanovic et al. [69] | BA-BI, |

| Kim and Lee [70] | DBA-DPQ, DBA-DBI, DPQ-DBI, DPQ-DBL, DBI-DBL |

| Kladou and Kehagias [71] | BA-BQ, BQ-BL, BA-BAS |

| Features | Variables | N = 435 | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 192 | 44.1 |

| Female | 243 | 55.9 | |

| Age | 18–29 | 105 | 24.1 |

| 30–39 | 171 | 39.3 | |

| 40–49 | 94 | 21.6 | |

| ≥50 | 65 | 14.9 | |

| Education | High School | 28 | 6.4 |

| Diplomat | 99 | 22.8 | |

| Undergraduate | 230 | 52.9 | |

| Postgraduate | 78 | 17.9 | |

| Employment Status | Employed | 246 | 56.6 |

| Self-Employed | 147 | 33.8 | |

| Retired | 42 | 9.7 | |

| Annual Income | Under USD 7000 | 21 | 4.8 |

| USD 7000–USD 14,000 | 157 | 36.1 | |

| USD 14,000–USD 70,000 | 225 | 51.7 | |

| Over USD 70,000 | 32 | 7.4 |

| Items | Mean | SD | Loadings | CA (α) | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIMC C | 0.884 | 0.600 | 0.983 | |||

| DIMC C1 | 3.320 | 1.134 | 0.772 | |||

| DIMC C2 | 3.270 | 1.148 | 0.756 | |||

| DIMC C3 | 3.280 | 1.189 | 0.786 | |||

| DIMC C4 | 3.360 | 1.167 | 0.791 | |||

| DIMC C5 | 3.380 | 1.172 | 0.767 | |||

| DIMC I | 0.884 | 0.587 | 0.982 | |||

| DIMC I1 | 3.330 | 1.160 | 0.747 | |||

| DIMC I2 | 3.290 | 1.137 | 0.757 | |||

| DIMC I3 | 3.370 | 1.168 | 0.781 | |||

| DIMC I4 | 3.360 | 1.140 | 0.783 | |||

| DIMC I5 | 3.350 | 1.203 | 0.763 | |||

| DBA | 0.872 | 0.619 | 0.893 | |||

| DBA1 | 3.360 | 1.157 | 0.772 | |||

| DBA2 | 3.420 | 1.129 | 0.786 | |||

| DBA3 | 3.440 | 1.198 | 0.774 | |||

| DBA4 | 3.460 | 1.180 | 0.814 | |||

| DBI | 0.865 | 0.605 | 0.889 | |||

| DBI1 | 3.360 | 1.131 | 0.802 | |||

| DBI2 | 3.340 | 1.160 | 0.773 | |||

| DBI3 | 3.310 | 1.163 | 0.794 | |||

| DBI4 | 3.390 | 1.183 | 0.74 | |||

| DPQ | 0.865 | 0.577 | 0.882 | |||

| DPQ1 | 3.320 | 1.250 | 0.751 | |||

| DPQ2 | 3.280 | 1.193 | 0.78 | |||

| DPQ3 | 3.350 | 1.212 | 0.749 | |||

| DPQ4 | 3.290 | 1.169 | 0.758 | |||

| DBL | 0.877 | 0.609 | 0.891 | |||

| DBL1 | 3.300 | 1.217 | 0.777 | |||

| DBL2 | 3.360 | 1.202 | 0.78 | |||

| DBL3 | 3.410 | 1.204 | 0.773 | |||

| DBL4 | 3.290 | 1.200 | 0.792 | |||

| DIMC_C | DIMC_I | DBA | DBI | DPQ | DBL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIMC_C | 0.775 | |||||

| DIMC_I | 0.346 | 0.766 | ||||

| DBA | 0.329 | 0.343 | 0.787 | |||

| DBI | 0.343 | 0.354 | 0.347 | 0.778 | ||

| DPQ | 0.390 | 0.339 | 0.401 | 0.386 | 0.760 | |

| DBL | 0.362 | 0.387 | 0.361 | 0.354 | 0.400 | 0.781 |

| Index | Value | Recommended Value | Acceptable Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 347.765 | |||

| d.f. | 287 | |||

| χ2/d.f. | 1.212 | <2 | 2–3 | Supported |

| GFI | 0.929 | >0.95 | 0.90–0.95 | Acceptable |

| RMSEA | 0.025 | <0.006 | 0.06–0.08 | Supported |

| RMR | 0.058 | <0.05 | 0.05–0.08 | Acceptable |

| CFI | 0.988 | >0.95 | 0.90–0.95 | Supported |

| TLI | 0.986 | >0.95 | 0.90–0.95 | Supported |

| Hypotheses | β | t | p | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1. DIMC C → DBA | 0.376 | 7.57 | *** | supported |

| H2. DIMC C → DBI | 0.371 | 7.454 | 0.004 | supported |

| H3. DIMC C → DPQ | 0.464 | 9.781 | *** | supported |

| H4. DIMC I → DBA | 0.415 | 8.517 | *** | supported |

| H5. DIMC I → DBI | 0.427 | 8.824 | *** | supported |

| H6. DIMC I → DPQ | 0.422 | 8.699 | 0.002 | supported |

| Relationship | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| DBA → DBI | 0.313 *** | - | 0.313 *** |

| DBI → DBL | 0.269 *** | - | 0.269 *** |

| DBA → DPQ | 0.395 *** | - | 0.395 *** |

| DPQ → DBL | 0.313 *** | - | 0.313 *** |

| DBA → DBL | 0.183 * | - | 0.183 * |

| H7. DBA → DBI → DBL | - | 0.084 | 0.267 *** |

| H8. DBA → DPQ → DBL | - | 0.057 | 0.240 *** |

| Relationship | Lower Bounds | Upper Bounds |

|---|---|---|

| H7. DBA → DBI → DBL Total Effect | 0.363 | 0.582 |

| Direct Effect | 0.182 | 0.427 |

| Indirect Effect | 0.105 | 0.259 |

| H8. DBA → DPQ → DBL Total Effect | 0.361 | 0.576 |

| Direct Effect | 0.122 | 0.382 |

| Indirect Effect | 0.132 | 0.308 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qi, M.; Abdullah, Z.; Rahman, S.N.A. Navigating the Digital Landscape: Evaluating the Impacts of Digital IMC on Building and Maintaining Destination Brand Equity. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208914

Qi M, Abdullah Z, Rahman SNA. Navigating the Digital Landscape: Evaluating the Impacts of Digital IMC on Building and Maintaining Destination Brand Equity. Sustainability. 2024; 16(20):8914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208914

Chicago/Turabian StyleQi, Meng, Zulhamri Abdullah, and Saiful Nujaimi Abdul Rahman. 2024. "Navigating the Digital Landscape: Evaluating the Impacts of Digital IMC on Building and Maintaining Destination Brand Equity" Sustainability 16, no. 20: 8914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208914

APA StyleQi, M., Abdullah, Z., & Rahman, S. N. A. (2024). Navigating the Digital Landscape: Evaluating the Impacts of Digital IMC on Building and Maintaining Destination Brand Equity. Sustainability, 16(20), 8914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208914