Abstract

Stakeholders and their dynamics are often neglected in innovation system literature. The importance of the bioeconomy is growing due to its implications for addressing environmental challenges, shaping economic decisions, markets, and sustainable development. This paper analyses stakeholders’ dynamics for knowledge creation and innovation to transit from unsustainable practices to the sustainable use of biological resources—the bioeconomy. The originality of this paper is the creation of an analytical framework to characterise the interactions of stakeholders and how these interactions reshape innovation systems to create a new narrative and knowledge-base platform for innovation. Using a qualitative approach, data were collected through surveys between 2022 and 2024. We explored the dynamics of 29 stakeholders involved and collaborating in R&D activities from the biotechnology sector in Caldas, Colombia. Our findings show that dynamics towards the bioeconomy are occurring only at the discursive level. Stakeholders carry out research activities to generate income rather than for innovative purposes, overlooking informal interactions that create novel ideas that could translate into solutions, services, and products. We conclude that the bioeconomy transition needs a systemic disequilibrium with a new institutional infrastructure that enables stakeholders, including civil society, to create a structural change for embracing innovation dynamics.

1. Introduction

The bioeconomy (BE) has been at the centre of sustainability discussions worldwide for the last twenty years due to major environmental, social, and economic challenges. These challenges and developmental trends require a radical change in the form of modernising the global economy [1,2,3]. This discussion anchors around applying biological principles and processes based on technical innovation to maximise efficiency and derive high value from bio-based resources in all sectors of the economy [4]. The bioeconomy emerged as an economic paradigm in science, technology, and innovation (STI) policy to minimise adverse the environmental impacts of economic activities, thereby aiming to achieve important sustainable development goals (SDGs) [5,6]. Transitioning to a bioeconomy involves efforts by a wide range of industries to replace fossil fuel inputs with renewable carbon sources along with resource efficiency and preservation of the resource values in material circles [7,8].

Studies on BE innovation predominantly focus on analysing strategies at the national level [9,10]. European countries have shown significant progress in developing policy strategies. However, these studies have focused on policies that promote structural changes towards a bioeconomy. Examples include policies that replace fossil-based raw materials with bio-based resources and principles [10], sustainable management of natural resources, climate change mitigation, and energy and food security [2].

Given this, there are studies that examine Latin American (Latam) countries. In the case of Colombia, analysis has shown that policies primarily champion a bioeconomy to cosmetically present bio-matters to render involved fields “capitalisable” and “rentier” [11,12]. From a political perspective, the policy-push pattern of the bioeconomy is similar across Latam geographies [12].

On the other hand, innovation studies related to the bioeconomy have encompassed a range of new products, i.e., fuels, new food additives and biopolymers [13,14], and novel processes, i.e., biorefining [15] and industrial biotechnology [16]. Although these studies focus on marketable products and services, there exists an overlooking of the role of interactions that result in these innovations [17]. Thus, our research addresses the importance of dynamics based on the innovation system (IS) literature and builds on studies that have demonstrated the impacts of different agents’ roles in ISs, i.e., knowledge and collaborative interactions in particular [18,19]. These roles and relationships of agents have explained the activities and intensity of R&D and the sources of funding on the one hand, and interfirm relationships and the role of the public sector on the other [20,21]. Similarly, on the national level, developed countries have adopted emerging technologies and aligned government, academia, and industries in collaborative activities to foster innovation [22]. While these studies have highlighted the efforts and the importance of bioeconomy innovation in both developed and developing economies, we argue that there is a need to provide a different focus on bioeconomy promises, particularly on the role of (biological and related) technological innovations in allowing the advancement of a sustainable way to manage renewable biological resources [12].

In addition, we expect that across European countries, national strategies could be similar; evidence shows that central and eastern Europe have opted for national bioeconomy strategies with slightly different socio-economic contexts, perspectives, and behaviours to support bioeconomy innovation [23]. While these studies have highlighted the significance of establishing a top-down approach and collaboration among industries and agents of ISs, it still needs to be determined how these collaborative activities come to exist where there is a coexistence of multiple interests and alignment with a national strategy. Therefore, this study is one of the first to focus on developing economic contexts with complex and multiple interests of industries and agents. Furthermore, although research has stressed that countries around the world take advantage of emerging technologies to leverage the use of natural resources to develop and grow bio-based industries, in emerging economies, it is still unclear how these alignments that foster innovation seem to occur. In this line of argument, the bioeconomy still has to deliver its potential, and in the case of Colombia, transitions are deeply contested, involving multiple possible visions and transition pathways [18,24,25,26] and fierce resistance from vested interests across sectors, i.e., the energy, petrochemical, agriculture, and forestry sectors [27,28].

Moreover, there have been several studies on the role of actors in the transition to sustainability, and thus the bioeconomy. These studies examine transitions, as well as the interactions and relations between the actors taking part in these transitions, as dynamic processes [29]. Thus, understanding collaboration among actors is relevant as it comes in many forms, i.e., some are focused on addressing technical challenges, while others are focused on challenging existing institutions and values [30]. Despite all the positive impacts of the bioeconomy such as environmental benefits, innovation, creation of new economic opportunities, new business formation, and the strengthening of knowledge-based sectors, recent research has addressed the innovation barrier for segments of the bioeconomy using the innovation system (IS) approach, generally at the national level [28,31,32,33,34]. Related assessments using the IS approach in the context of Latam have addressed the transition to the bioeconomy [35,36,37]. These studies have mainly focused on system failures, although ISs in Latam exhibit presence and coordination among actors to support innovation. This paper examines stakeholders, placing them into ISs with their agency, which describes whether and how they shape innovation in the bioeconomy.

Furthermore, in this research, we examine the dynamics of stakeholders in ISs concerning innovation to transit to bioeconomy. By addressing this research gap, we aim to make a theoretical and empirical contribution to literature. Our theoretical contribution derives from introducing elements of ISs, particularly Technological Innovation Systems (TISs) and linking them with stakeholders rather than actors or agents. Our study reframes these elements in ISs, placing emphasis on the element of agency in stakeholders which impacts on innovation and thus bioeconomy transition. The empirical contribution comes from examining the dynamics of stakeholders of the biotechnology sector in Caldas, Colombia. We address the question as to why, despite the awareness amongst critical stakeholders of the importance of a bioeconomy for the sustainability of the Caldas economy, and the existence of institutions in the form of local and national laws, there still exists a lack of an effective transition from a fossil fuel economy to a bioeconomy.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: The next section elaborates on the theoretical framework. We elucidate the methodological approach to answering the research question. Then, we present our results, considering the elements of the theoretical framework. We discuss the implications of the dynamics of stakeholders, considering the literature on ISs. Finally, we present the conclusions.

2. Theoretical Framework

We take the Technological Innovation System approach (TIS). A technological system may be defined as a network of agents interacting in a specific economic or industrial area under a particular institutional infrastructure or set of infrastructures and involved in the generation, diffusion, and utilisation of technology [38]. Technological systems are defined in terms of knowledge/competence flows rather than flows of ordinary goods and services [39]. From the TIS approach, the required changes in production processes, resource use, and integration of civil society associated with bioeconomy concepts call for system innovation, including changes in the architecture and components of the entire sectoral (or sociotechnical) system [40]. One key aspect of TISs is that they are multi-dimensional. In most cases, the constituent elements (knowledge/competence networks, industrial networks/development blocks, and institutional infrastructure) are especially correlated [39]. Although agents in innovation systems are often seen as key drivers of sustainability transitions, stakeholders are merely mentioned in innovation systems literature. Therefore, we argue that the field lacks a systemic investigation of scientific knowledge for innovation and its barriers and drivers from the stakeholder perspective [41].

Conceptualised as one of the main functions of innovation systems [42], the dynamics of stakeholders’ activities and their embeddedness in innovation systems still lack theoretical foundations [43]. Tracing ongoing transitions requires attention to the dynamics of the interactions of stakeholders and other system components. To enable civil society, policymakers, and stakeholders to assess the impacts of their dynamics on bioeconomy, a systemic assessment of the dynamics of bioeconomy innovation is needed. Thus far, little is known about the stakeholders, be they companies, universities, public and private research organisations, or local government agencies, about the attention to risk, synergies, and trade-offs. To our knowledge, research needs to incorporate how stakeholders experience, i.e., their vested agency, and how they shape complex processes such as innovation and, thus, transformation.

Based on this background, we build our framework using studies of Technological Innovation Systems (TISs) at the stakeholder level. Studies of TISs have focused on agents, firms, and entrepreneurs, stating that innovation requires the perception of opportunities to change existing routines productively, their willingness to undertake such changes, and the ability to implement these changes [44]. For innovation to occur and produce changes, stakeholders are aware of their capabilities and values and continuously scan their environment for risk, opportunities, and change with uncertain outcomes [45]. Furthermore, to effectively transit to bioeconomy innovation requires collaboration between firms, universities, research organisations, and government agencies to produce knowledge to ultimately change the routines, as previously mentioned [21,46,47].

Previous research has examined factors that impact the collaboration between stakeholders. For example, the analysis of universities as a factor for new knowledge generation and technology transfer has had a significant impact on entrepreneurs and companies at the regional level [48]. Likewise, research has examined the growing role that end-users play in regional project-based innovations [49]. However, there is also evidence showing factors that impact innovation, such as the actors that make up the innovation ecosystem, how these actors impact successful knowledge-transfer cases, and the interrelationships between the factors leading to knowledge transfer [50].

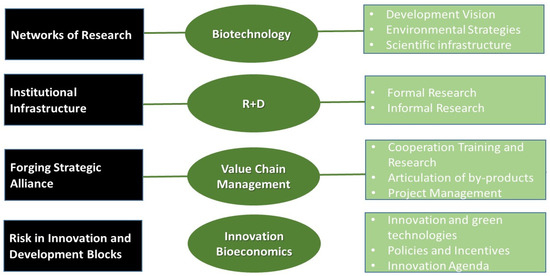

Therefore, our framework examines networks in TSI that indicate that successful innovation seems to require interaction among stakeholders with different competences. The nature of innovation is uncertain and complex; therefore, networks provide other alternatives for governing innovation [38,39]. Institutional infrastructure refers to a set of institutional arrangements that directly or indirectly support, stimulate, and regulate the process of innovation and the diffusion of technology [39,51]. Development blocks are dynamic in nature and incorporate the characteristics of disequilibrium. These blocks create tension within the technological system that varies in strength and composition over time and generates development potential for the system [51].

The TSI approach is useful because it makes it possible to describe, understand, and explain the innovation process. It enables us to identify the factors that shape innovation [21]. It allows us to map out and explain interactions between stakeholders that generate knowledge, especially across a diverse range of stakeholders involved, including governmental organisations, businesses, non-governmental organisations, local communities, scientists, farmers, and civil society. These stakeholders assume distinct roles in policy formulation and implementation, research and development, and the production and consumption of biotechnology products. The contributions of each group of stakeholders are crucial in promoting and advancing the sector towards a bioeconomy.

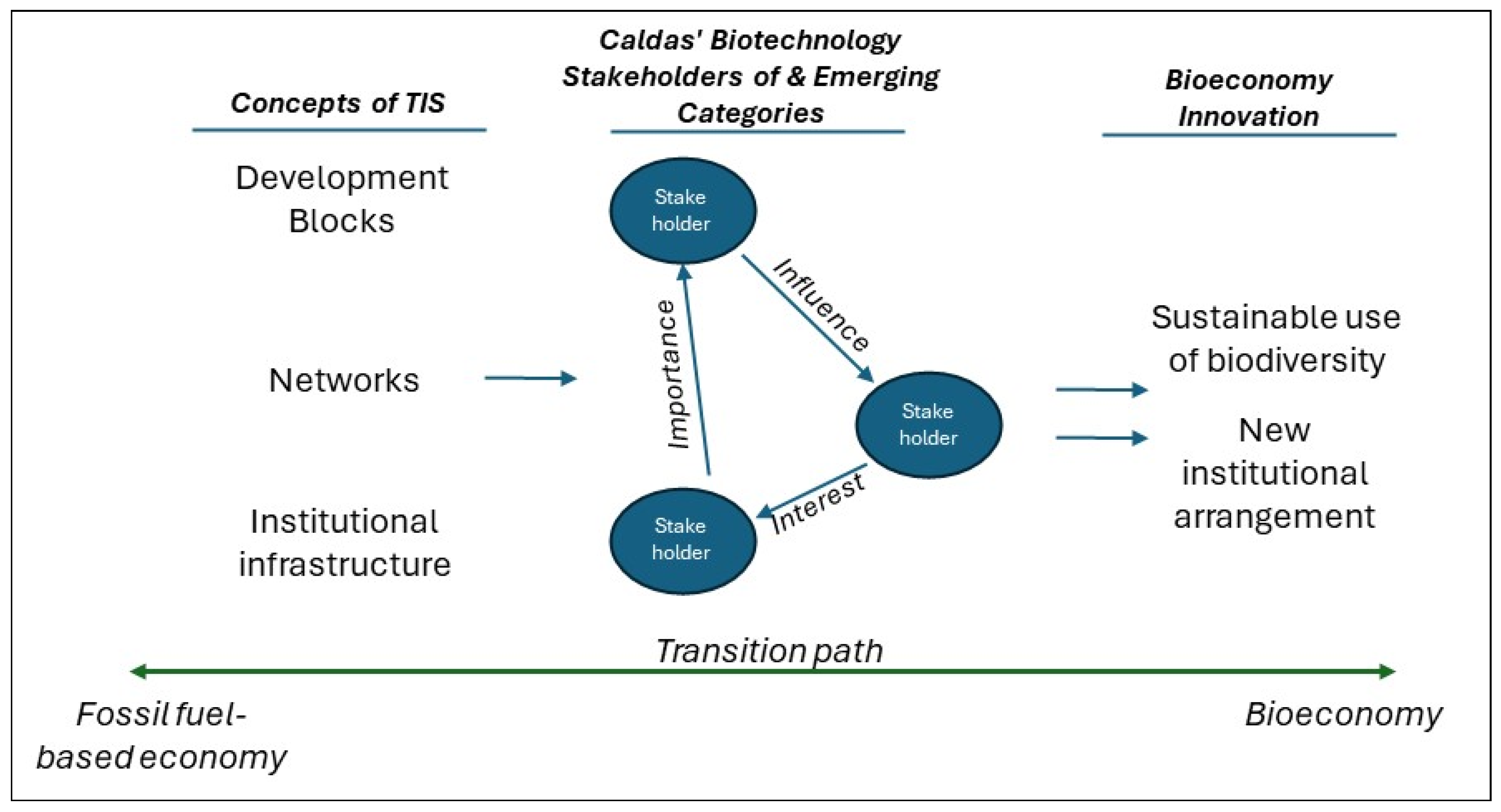

However, in our research context, in the activities of the stakeholders, three distinctive elements interrelate with what constitutes an explanation of why the transition towards a bioeconomy has yet to be up to the global challenge. We identified three main categories: (1) importance, (2) influence, and (3) interest. These three emerging categories were recurrent across all stakeholders including private and public organisations. The perception of every stakeholder regarding research activity undertakings and the translation of these research results into change and implementation entails risk-taking and a long-term vision of innovation.

Figure 1 illustrates that our framework depends on the importance, influence, and interest of stakeholders in light of the perceived innovation opportunities in the biotechnology sector of Caldas, Colombia. We explain these different elements in more detail below. The importance of specific stakeholders within the biotechnology sector lies in their ability to shape its trajectory. Their importance shapes stakeholders’ innovation. For example, government organisations can create regulations and policies that either facilitate or impede investment in biotechnologies. Research reveals that preferences shape innovation. For example, genuine concerns can drive environmental innovation [45,52]. In this line of argument, public and private universities, technical schools, and research centres contribute to research and development with their wealth of knowledge and expertise.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of theoretical framework. Source: Own elaboration.

In this article, influence is the capacity of stakeholders to shape decisions and policies that impact the biotechnology sector. Stakeholders can exert their influence through various means, including political, economic, or social power. The structural properties of relevant ISs and TIS policy can influence the prevalence of innovation among firms [53,54,55]. For instance, governments can establish regulations and policies fostering or hindering the transition towards a bioeconomy. Similarly, businesses can leverage their economic power and technological prowess to influence a bioeconomy. Influence in stakeholders indicates the ability to leverage, combine, and recombine knowledge and resources so that new products, technologies, and markets result [56]. Non-governmental organisations, alternatively, can mobilise public opinion and advocate for sustainable approaches.

The participants in bioeconomic activities are propelled by unique objectives and motivations, directly shaping their interests. Stakeholders’ interests can diverge considerably, with commercial entities often prioritising profit maximisation and local communities emphasising public health and environmental protection. A meaningful understanding of these interests is indispensable for fostering productive stakeholder collaboration. By recognising and comprehending the interests of all stakeholders, it is possible to establish a more cohesive and cooperative environment, leading to more effective outcomes.

Our conceptual framework sheds light on the structural components (i.e., Stakeholders network, institutional infrastructure, and development blocks) of innovation that are in continuous interaction with and, therefore, shaped by Importance, Influence and Interest. The intricate interplay between stakeholders’ importance, influence, and interests can give rise to complex tensions. Stakeholders with significant importance and influence can often exert their interests at the expense of others. Achieving this balance is crucial to the long-term success of the bioeconomy, and it requires a strategic and collaborative approach that considers the diverse concerns and perspectives of all stakeholders involved. The conceptual framework highlights the embeddedness of stakeholders’ innovative behaviours and the related outcomes. Therefore, it is essential to recognise the various roles of these stakeholders in a bioeconomy and ensure that their interests align with long-term bioeconomy goals.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Selection and Research Tools

We focused our research on the Department of Caldas, Colombia, and the biotechnology sector (see Figure 2). Caldas has set an agenda anchored around a comprehensive national Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) TIS programme to promote the transition to a bioeconomy [57]. For over 25 years, the national government of Colombia in partnership with the Caldas departmental and municipality government levels, have implemented a series of initiatives and projects to develop clusters in various sectors, biotechnology being one of them. The biotechnology cluster was developed through technical committees. These committees addressed issues such as identifying and summoning companies, government agencies, and organisations related to the biotechnology process and research that culminated in the foundation of the biotechnology cluster of Caldas in 2019 [58]. Therefore, the study’s key objective is to examine stakeholders’ dynamics in the creation of knowledge despite the institutional framework to support innovation based on science and technology by the biotechnology sector in Caldas (Colombia).

Figure 2.

Map of the Department of Caldas in Colombia. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plantilla:Mapa_de_localizaci%C3%B3n_de_Caldas#/media/Archivo:Colombia_Caldas_location_map_(+locator_map).svg (accessed on 18 November 2024).

In 2019, the national government of Colombia carried out an initiative to conduct a comprehensive technical assessment to create a roadmap toward the bioeconomy of the entire country. In 2020, shortly after this initiative, the departmental government of Caldas followed the steps of the national government and conducted a similar but local technical assessment to further take Caldas towards a bioeconomy and sustainable economic competitiveness. The bioeconomy is strategically important at the national and department government levels in all productive sectors, particularly life-science and biotechnology. However, the technical assessment elucidated that efforts were required to understand how to further incentivise innovation in the bioeconomy. Hence, when looking at the agglomeration of the stakeholders of this cluster, it was logical to examine their dynamics based on bioeconomy promotion. The stakeholders’ involvement in collaborative R&D and learning sheds light on efforts related to TISs that ultimately impact the bioeconomy transition.

The research was carried out between 2022 and 2024. The method used was qualitative research based on interviews. Qualitative interviews are the method that allow for understanding and meaning to be explored in depth because they help to examine the context [59]. Interviewing is a powerful way of helping people to make explicit things that have hitherto been implicit, to articulate their tacit perceptions, feelings, and understanding (p. 32). Given the qualitative nature of this research, there was no need to establish a representative sample of stakeholders for which statistical analysis would not be appropriate. This provided flexibility in terms of stakeholders to look at. The purpose of this was for participants to acknowledge themselves as a stakeholder. This involved initial informal discussions to establish a baseline and identify critical participants and their level of involvement.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

We conducted interviews by implementing surveys by using the virtual tool “Google Forms”. The first survey was carried out in 2022; we invited 172 stakeholders, out of which 40 participated. The second survey was conducted in 2024, inviting 226 stakeholders, with 29 responding (see Table 1). The questionnaire of the survey combined the theoretical elements discussed in Section 2, took about 40 min to answer given the open-ended questions, and was conducted with the owners, the managing director and, when existing, the director of research at the stakeholder’s place of work. The questionnaire also constructed the baseline for a qualitative mapping of the stakeholders with the validation of other stakeholders in the sector.

Table 1.

Profile of stakeholders in the study.

Before sending the questionnaire, we approached stakeholders via email and phone calls. This approach proved appropriate and enhanced professionalism on our side as researchers which gave the level of assurance the stakeholders needed. This also allowed us to build rapport as we explained more about the project, making it clear that we were not interested in financial information, prices, customers, etc. We provided participant information and attained informed consent in emails and verbally during phone calls. A brief leaflet was elaborated and enclosed; on phone calls, it was briefly introduced, containing information on the research, i.e., the objectives and the focus of the research and an explanation of why their participation was important. It explained the topics that would and would not be covered, i.e., money, financial statements, and negotiation arrangements. We explained the data handling and privacy issues and reassured them they could withdraw from the research at any time.

The Thematic Analysis Approach (TA) was utilised because it ensured the robustness of the methods used and the qualitative nature of this research and provided transparency in relation to the analytical process [60,61]. We read all answers and then used Nvivo 12 Plus software to create labels (indexing) and a manageable way of looking at the data. The next stage consisted of transforming the labels into codes according to concepts of the literature such as TIS and three emerging categories: importance, influence, and interest. Using TA, we organised the analysis according to the systematic requirements of this method. It provided the possibility to trace the interconnectedness stages and links between accounts to explain and construct a thorough account of the case. TA enables the description of analysis from the initial management of data through the development of descriptive to explanatory accounts [60] (p. 55). Finally, as part of constructing the stakeholder map, three experts rated the stakeholders in three categories that explained the interactions taking place in the TSI: interest, importance, and influence on a scale from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high). We then assessed the relative weight of each category within the network as follows: 45% (importance), 30% (influence), and 25% (interest), and recalculated the ratings accordingly. During this step, we ran a multivariate analysis using the principal component technique to examine the data exported to the statistical program SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science). Subsequently, we performed cluster analysis and used a dendrogram to group stakeholders according to their interests, importance, and influence. Then, the stakeholders map was constructed, and each resulting group was characterised and typified.

4. Results

In this section, we present our findings from the empirical analysis and shed light on the research question:

Why, despite critical stakeholders’ awareness of the importance of a bioeconomy for the sustainability of Caldas’ economy and the existence of institutions in the form of local and national laws, does a lack of effective transition from a fossil fuel economy to a bioeconomy exist?

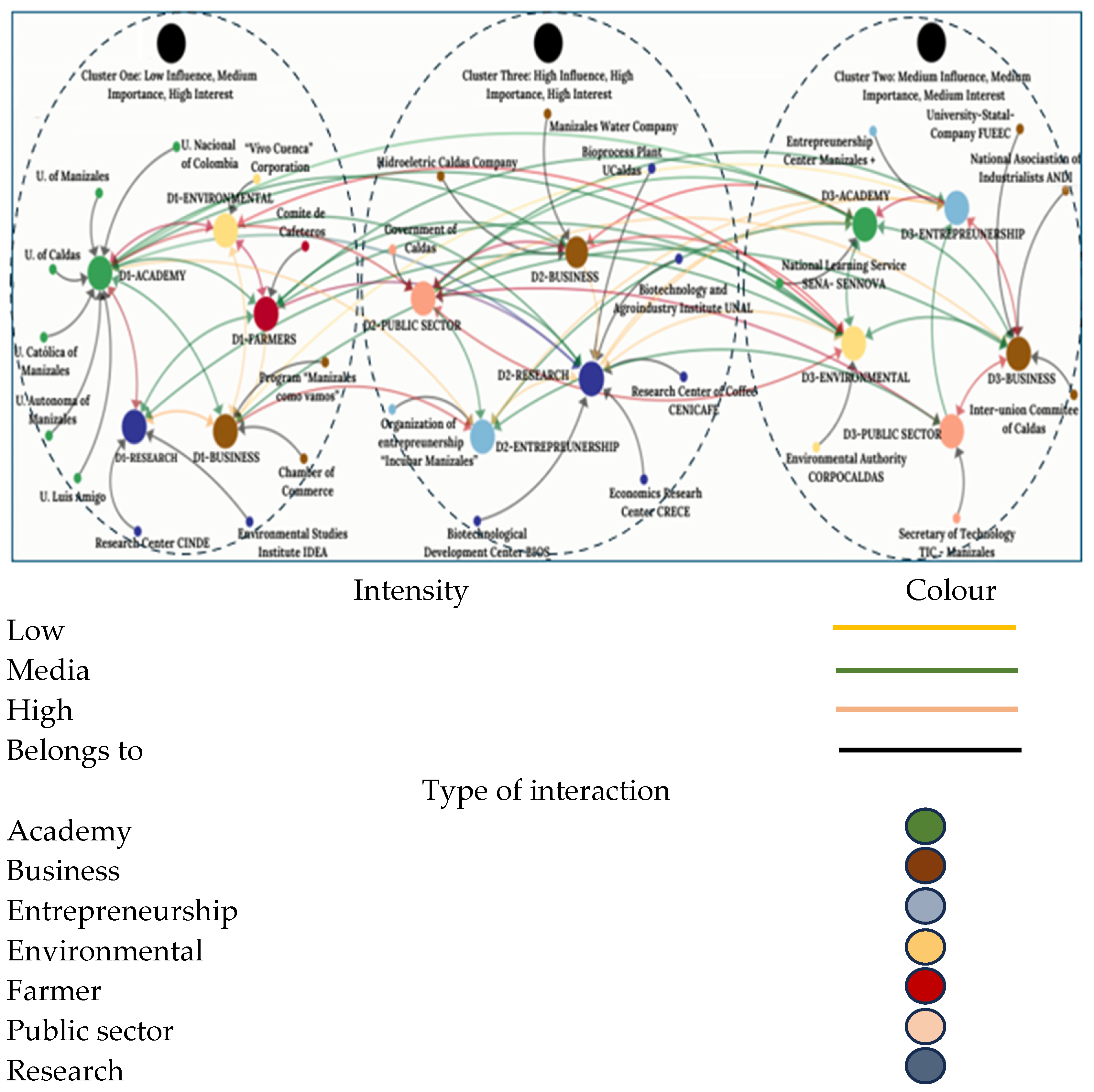

The examination of the dynamics of stakeholders in Caldas’ biotechnology sector shows that there has been substantial public investment along with private efforts. The investment carried out during the past 25 years has been geared towards creating a biotechnology cluster with stakeholders (companies and public organisations) and a clear perception of what a bioeconomy and its transition entail. Figure 3 illustrates the complex interplay between stakeholders of the biotechnology sector in Caldas, with three clear clusters of stakeholders with different degrees of importance, influence, and interest. In cluster one, stakeholders show low influence, medium importance, and high interest. In cluster two, stakeholders show medium influence, medium importance, and medium interest. In cluster three, stakeholders show high influence, high importance, and high interest.

Figure 3.

Map of dynamics of the stakeholders of the biotechnology sector of Caldas, 2023.

Acting upon the network, R&D collaboration among stakeholders is recurrent, showing activities based on TISs. These collaborations create a knowledge pool with innovation potential. In this way, the institutional infrastructure allows the creation of strategic alliances that positively affect the network in terms of blocks of stakeholders. When looking at the articulation of this TIS, the dynamics of stakeholders have developed based on their importance, influence, and interests, less related to innovation and more to the promotion of a bioeconomy. Likewise, the institutional infrastructure is supportive of formal arrangements; it overlooks other possibilities that can translate into innovation. Furthermore, most stakeholders understand innovation and bioeconomy, but only a few really embark on the risk-taking aspect of innovation. In the following sub-sections, we present the findings in more detail.

4.1. Networks of Research

Our analysis from interviews indicates that project management for research stands out as the most prevalent among the various forms of engagement. Stakeholders point out that research is of great importance. The map shows that in cluster one, most stakeholders are universities, and only three NGOs are dedicated to the interests of businesses. The map shows that stakeholders are highly interested in conducting scientific research. This is especially evident when stakeholders require context-based solutions which consider the local natural endowment and the sector’s requirements. Stakeholders also assert that the biotechnology sector needs to show vision and imagination regarding the development of waste-utilisation alternatives as strategies to address environmental and climate change challenges. Most views highlight the importance of universities and business chambers advancing the sector toward a bioeconomy.

The data indicate that national and local government administrations promote calls for funding various bioeconomy research projects. Universities engage with the productive sector in putting together bids for funding. This recurrent engagement involves supplementing scientific research capabilities, dividing work packages based on institutional expertise, and delivering reports, scientific articles, and patents. One clear example of research funding is the articulation of several higher-education institutions engaged in biotechnology and environmental research and development such as “Implementation of a comprehensive strategy through biotechnological innovation for the utilisation of waste in the Department of Caldas”, executed between 2013 and 2019.

Scientific infrastructure for project execution still needs improvement, being of medium importance to the outcomes of these research projects. Due to the low influence stakeholders can exert, even though public universities typically possess the most infrastructure, their decreased influence poses challenges related to financial resources. In this line of argument, stakeholders identified two structural issues. Researchers reported hindering factors for innovation, for example, the need for more time to carry out significant research by reducing teaching hours and allowing academics greater flexibility in managing their schedules. With this, researchers can work more effectively towards patent production, innovation, and technological development.

Researchers and business associations also state that projects are a means of funding. This funding is a survival mechanism necessary to comply with academic performance indicators. Generally, universities dedicate significant time and human resources to comply with publications and formal collaborations with other universities and research centres. These indicators are based on the contractual arrangements universities have as an effect of participating in research projects.

4.2. The Formal and Informal Institutional Infrastructure

Research projects encompass practical solutions and interventions for the biotechnology sector in Caldas. For instance, the University of Caldas houses the Technological Development Centre in Bioprocesses and the Agroindustry Plant, recognised by the Ministry of Science (Minciencias). Since its inception in 2012, this research centre has executed numerous research projects and currently possesses various bioproducts and processes ranging from three to nine in terms of Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs). Examples include the production and distribution of mushroom seeds of several macrofungal species with medicinal attributes and nutritional properties to mushroom growers.

However, when we further explored interests with stakeholders regarding research and innovation, although they categorically stated it as necessary for the sector’s transition to a bioeconomy, stakeholders repeatedly argued that alongside formal research, contractual mechanisms, and relationships, the “real” innovation has a robust informal component. One university stakeholder said the following:

“Alongside the (research) project we are currently undertaking, we have had several informal meetings that have arisen spontaneously to discuss specific matters of various issues. It turned out that as a result of these informal interactions, exciting ideas emerged, and it is what we have been concurrently working on” (Stakeholder A, November 2023).

The participation of universities and businesses in research bids is in line with calls to tackle issues that may or may not entirely address Caldas’ contextual issues. These formal mechanisms encourage these stakeholders to gather to think about the issues at hand. In this regard, stakeholders act tactically rather than critically to obtain funding and subsequently comply. According to our interviewees, “innovation encounters” in the form of informal meetings should be encouraged to promote innovation through research. Such encounters have already taken place to promote innovation through research, with entrepreneurs and businesspeople from across Caldas and from various value chains participating. This type of collaboration with research groups at universities should further explore how current research centres can be used to develop, enhance, or solve current value chain-related issues. What is clear is that informal interaction with entrepreneurs, some financial entities, and government bodies could allow a more flexible space for discussing issues and developing ideas to provide comprehensive and innovative solutions. Therefore, these significant interests rise towards exploration and a search for alternatives that can accelerate solutions and the transition to a bioeconomy.

4.3. Forging Strategic Alliances

One of the most interesting findings was the crosscutting nature of replicating trending discourses such as innovation, bioeconomy, and sustainability. In the map, cluster two illustrates a structure predominantly comprised of private organisations oriented towards supporting biotechnology companies. Stakeholders believe it is vital to identify other companies involved in processing food and agriculture. When stakeholders were asked what their understanding of bioeconomy and sustainability was, what was apparent from the responses was a repeated discourse of wanting to sound and appear concerned about the future of the biotechnology sector and sustainability, as illustrated by some of the respondents below:

“When discussing with our counterparts in Bogota, we are always told that we dress up and smell very nice when we talk about this type of issue (biotechnology, bioeconomy and sustainability), but we do very little when it comes to transforming the sector” (Stakeholder B, November 2023).

Furthermore, there is interest from the stakeholders in beginning to mobilise towards a bioeconomy. The significance of these stakeholders lies in their efforts to forge alliances or agreements with research centres, companies, and business organisations for cooperation in training, mentoring, and research projects facilitated by local and departmental government intervention. However, based on the statement above, this interest does not translate into real action regarding transforming the sector into a bioeconomy.

There are other specific examples where strategic alliances have forged benefits between companies in the biotechnology sector. For instance, Bilröst Craft Beer, a craft beer production company, supplies liquid yeasts, a by-product of beer brewing, to Ankor, specialising in plant nutrition. These liquid yeasts are vital for Ankor’s production of organic acid products, amino acids, fulvic acids, soluble crystals, and plant extracts. In seeking to understand the influence of this cluster, one key stakeholder explained that when establishing strategic alliances that promote the value chain into a bioeconomy, the top management of organisations must address and support these initiatives. They should not solely originate from an engineering department, academics, or innovation department, as these initiatives require resources and a full understanding from top management.

Moreover, stakeholders view their relationships with private companies, NGOs, research centres, and universities (both public and private) as favourable, characterised by bilateral communication facilitating the exchange of ideas and projects. Due to their perceived importance, this favourable view extends to departmental and municipal government levels. Notably, despite the private nature of these stakeholders, relationships with financial sources such as private banks have little influence, with stakeholders prioritising strengthening their ties with universities, research institutions, and government entities at various levels. Less frequent are informative, strategic alliances, and organisational relationships. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that strategic relationships between sector companies can impact value-added processes despite their infrequency.

4.4. Risk in Innovation and Development Blocks

Given innovation’s crosscutting and uncertain nature, it is unsurprising that all stakeholders have an aversive view towards embracing and investing in innovation. In response to this question, stakeholders highlighted how acutely aware they are of the need to invest in new technologies. This is especially highlighted amongst younger generations of leading companies. For example, there has been a slow growth of critical voices advocating for the acquisition and development of technologies to tackle issues such as nature conservation and water stewardship. This new wave of young adults is part of the generation of entrepreneurs who are beginning to take on the leadership of many prominent and influential companies. Many of them have pursued education opportunities abroad. This trend is partly facilitating a change, given what it takes to transition towards a bioeconomy and thus set an agenda which responds to territorial needs.

We explored various questions on the issue of risk management. Looking specifically at generational change, senior management was deemed to have a less forward-looking perspective regarding decision-making. Most managers still require at least a basic grasp of innovation or, better still, a complete understanding. The dominant view is one of wanting immediate returns on any investment in innovation, with innovation at the core of the territorial agenda. Overwhelmingly, all stakeholders are united in stating that if innovation were accessible and “easy to do”, it would not be innovation.

It is essential for the territory that business leaders comprehend the implications of innovation and understand which innovations could help to bolster a biotechnology sector. Linking back to our earlier discussion, cluster three holds significant sway over its relationships with other biotechnology companies and government agencies at the department and municipal levels in that it can pave the way to manage risk among stakeholders. The influence of the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros (FNC) is significant in setting the progressive use of green technologies for coffee production. Along with coffee production, this group’s influence over universities (both private and public) and scientific research organisations is considerable. Apart from the influence of FNC stakeholders, its importance resides in shaping how potential innovation prototypes and ideas are presented. According to them, adjusting business language is part of the need for greater innovation adoption.

A similar trend is discernible in the relationships between national and local governments, wherein influence is generally high. This influence is perceived as something to tackle that changes the survival pattern of other stakeholders, including research institutions, aligns resources with scientific projects, shifts the focus towards the territorial agenda, and tackles issues by developing actions, activities, or programmes. Stakeholders within cluster three endeavour to cultivate more extensive connections within the private sector, particularly with international corporations, universities, foundations, and research bodies. For example, stakeholders associated with Aguas de Manizales (water utility company) are notably prominent within the biotechnology cluster and are capable of assuming risk and influencing risk-related policies.

5. Discussion

5.1. Integration of Stakeholders and Their Importance, Influence, and Interest in TISs

At the theoretical level, our framework addresses a significant gap that IS literature overlooks at the micro level. We offer a new bottom-up perspective on innovation systems by addressing stakeholders rather than actors or agents and integrating the agency as the importance, influence, and interests of the stakeholders. The attention to IS research has been paid to systems failure [62]. In a context such as Latam, there exists a policy framework and discourse [12], specifically in Colombia’s case. Our results highlight that networks show dynamism among stakeholders with the purpose of creating knowledge for innovation, and stakeholders’ interactions consider their importance, influence, and interest. In this sense, incorporating our framework allows us to point out what stakeholders actually have at stake in light of belonging to a sector (network) that is crucial for the sustainability of the department and connecting innovation research to a bioeconomy. Interaction patterns between stakeholders have revealed several key insights regarding complex dynamics. Despite the discourse on the importance of a bioeconomy, few stakeholders carry out activities that are in line with a bioeconomy transition. The structure of the biotechnology sector requires change to achieve an effective transition towards a bioeconomy. The biotechnology sector reminds us that it is not only appropriate but fundamental to design territorial agendas. Caldas shows that stakeholders are setting a pathway at a discourse level. This has employed financial, technology, and knowledge resources, producing further scientific knowledge and data as a repository for potential innovations. Contrary to the research results examined in emerging economies, which state that Colombia has adopted a sectoral and more comprehensive national bioeconomy strategy, this analysis indicates that such a strategy has been insufficient to move forward and places the emphasis on the need for a more territorial strategy [36].

5.2. Implications for TISs for Transitioning to a Bioeconomy

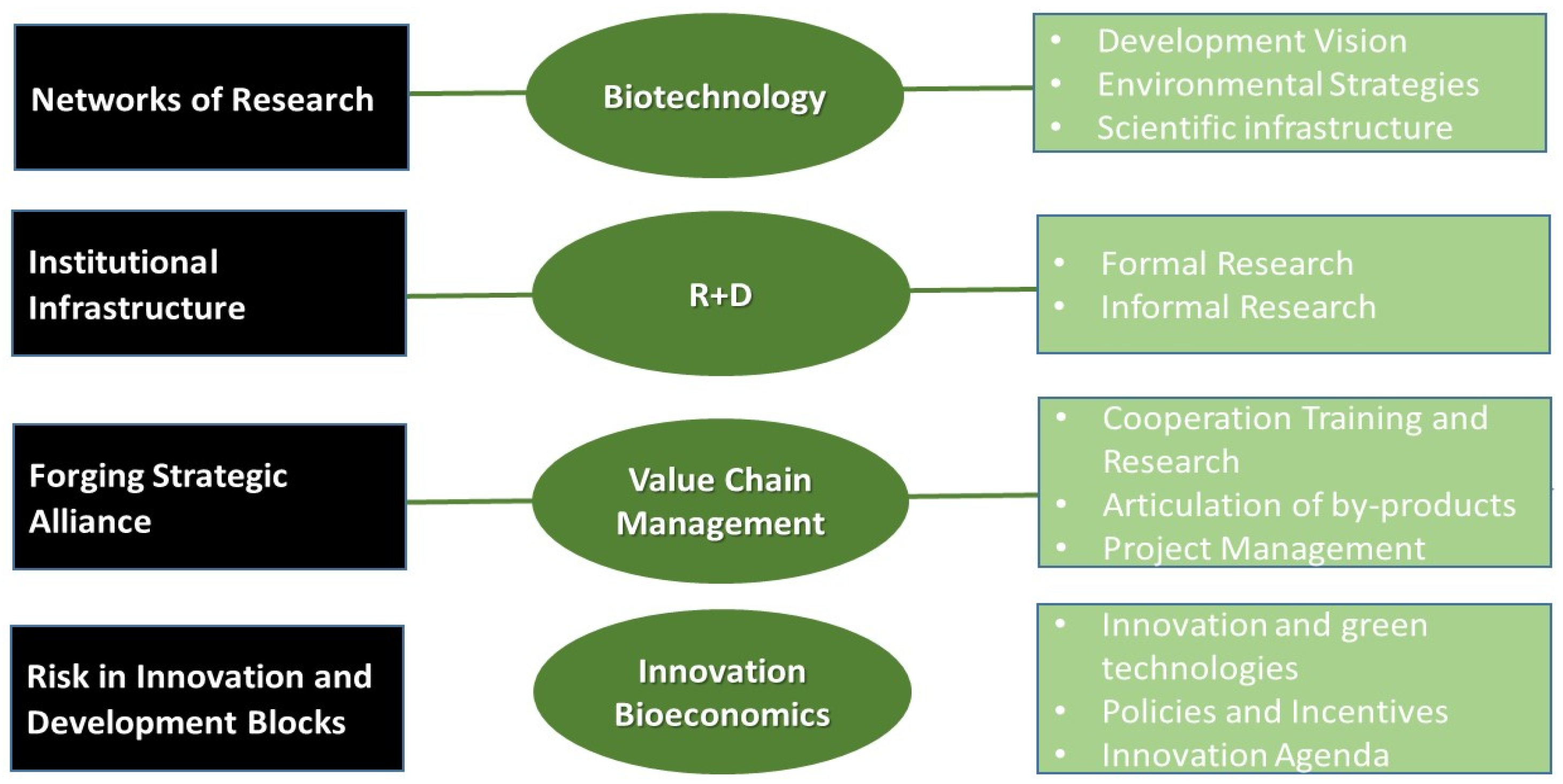

Empirical results shed light on the implications of including these three emerging categories for explaining the innovation opportunities that require the modernisation of materials and product testing processes and standards, among others [44]. The departmental and territorial focus was reflected by stakeholders highlighting the hindering factors affecting the transition to a bioeconomy (see Appendix A). Drawing from the experiences of developed economies, there is consistency in the idea of setting up territorial strategies addressing the needs and tackling the local issues of the biotechnology sector of Caldas. Some studies indicate the importance of addressing sectoral issues for setting up bioeconomy agendas [63]. Other studies shed light on the essentiality of having regional perspectives, thus focusing stakeholders on identifying the challenges and taking on the opportunities associated with technological developments (see Appendix C) [64].

The territorial agenda could catalyse the implementation of sustainable bioeconomy regions by diversification. Research in European contexts discusses Finland’s case, which illustrates a regional perspective where the forestry sector indicates that companies must diversify their current network structure and create new opportunities for smaller-scale enterprises [32]. Thus, this network structure will open new opportunities for “niche” small-scale companies. In Caldas, however, biotech companies and organisations position themselves in relatively comfortable activities within the value chain which pose less risk. The economic renewal or adaptation of the region and the creation of new developmental pathways can be seen as a combination of enterprise and system agency [65]. Such agency incorporates perspectives on enterprise dynamics and interactions within the productive and research systems, governmental entities, civil society, and other public and private institutions.

Caldas also indicates that territorial agendas are needed to solve issues such as (i) resistance to risk-taking and innovation, (ii) limited inter-stakeholder coordination and alignment, and (iii) the prevalence of a short-term focus on immediate returns rather than long-term sustainable development. Theoretical and practical notions suggest investigating the dynamic capabilities of various stakeholders to sense change, seize opportunities, restructure organisations, and examine the coherence of regional dynamic capabilities to forge new development paths [66]. However, our analysis illustrates that most stakeholders feel constrained by risk aversion, preferring proven, incremental innovations over more disruptive approaches. The bioeconomy endeavour necessitates thorough research into the capacities of business organisations, public institutions, and supporting bodies. It seeks to identify specific learning needs and new knowledge to acquire competencies, defining new organisational and institutional roles in response to the complex challenges of a knowledge-based bioeconomy.

Additionally, our analysis suggests that many stakeholders are concerned with short-term financial gains rather than the societal and environmental benefits of a bioeconomy [67]. Green innovations are more complex than traditional innovations, involving a broader range of stakeholders and exhibiting more significant ambiguity, with stakeholders frequently presenting conflicting demands [68]. This reflects a need for a shared, long-term vision, and commitment to a bioeconomy development agenda. In this regard, there are excellent examples of how stakeholders are supporting deeper collaboration and new knowledge dissemination that could decrease risk aversion [69]. A territorial bioeconomy strategy which engages all relevant stakeholders, aligns their interests, and encourages collaboration and risk-taking is crucial to enhance collaboration and knowledge dissemination. In these processes, regions provide resources and access to local and non-local information, influencing the accumulation, reproduction, and recombination of resources (especially tacit knowledge) and capabilities through the actions and interactions of local agents [70]. Such a strategy should be tailored to the specific context and resources of the Caldas region, drawing on its unique strengths and opportunities [71,72].

A redirection of focus, influence, and priorities is required to promote innovation in support of the transition and development of a bioeconomy [32]. Participation in decision-making and interaction between diverse stakeholders become necessary preconditions for risk-taking and sharing in the end result. Additionally, research suggests that fomenting a territorial approach which facilitates social learning and the generation of shared visions is critical for the sustainability transition. The case of Caldas indicates that transitioning towards a sustainable bioeconomy requires sectoral strategies and concerted territorial efforts to align stakeholder interests, foster collaboration, and promote long-term, sustainable development. This is supported by studies in which multiple interactive aims and stakeholder groups can be associated with considerable uncertainty [73].

Unlike the transition cases towards a bioeconomy, particularly in Latin America, or like those seen in Brazil and Thailand [69,74,75,76,77], Colombia lacks the presence of dominant stakeholders with large landholdings or a predominant economic presence dominating technological innovation such as in the case of palm oil plantations in Brazil [78]. However, when incorporating stakeholders into a call for proposals, the matrix of dominant power may include stakeholders who control and dominate economic resources such as loans or government support, or public policy, whose influence is so significant that all public investment is directed towards these stakeholders. This is an issue that requires governance (see Appendix B) [79].

Finally, the biotechnology sector in Caldas has adopted a transition to a bioeconomy not much different of other cases in Latin America in that it is conservative in nature and generally reproducing unsustainable processes often disguised under the sustainable label. The evolving dynamics of stakeholder interests, influence, and importance are critical considerations. Over time, stakeholders’ roles and interactions within processes can transform. Future research must examine the shift of stakeholders’ interests, influence, and importance.

6. Conclusions

Our study explored the dynamics of stakeholders in the biotechnology sector in Caldas. In these interactions, we examined the creation of knowledge for innovation to transit to a bioeconomy. In the theoretical framework, we introduced three emerging categories: importance, influence, and interests, and reframed agents for the stakeholders. The study takes IS analysis beyond its focus, predominantly failures, by considering stakeholders’ vested agency when it comes to knowledge creation, innovation, and thus impacts on transition towards a bioeconomy.

From our empirical results, it becomes clear that stakeholders reveal a complex interplay between their importance, influence, and interests. The development of a TIS in the biotechnology cluster of Caldas sheds light on the intervention and disequilibrium created by stakeholders such as those at the national, departmental, and municipality government levels. Furthermore, putting together companies and public and private organisations proves that stakeholders can begin to create development blocks. Our analysis shows that stakeholders are on the pathway to a bioeconomy at the discursive level. In line with the literature, these dynamics result in minimum structural change to allow tangible transition for the sector into a bioeconomy. The analysis highlights the need for a more cohesive and cooperative environment to foster sustainable bioeconomic development. Some stakeholders are dedicated to the formulation and management of research projects mainly for the purpose of generating flow of income, veering off from carrying out research that results in innovations that enhance the development of the biotechnology sector and boost productivity.

Our study also shows that few stakeholders have a real commitment to forging strategic alliances to enhance innovative capabilities and transform the current socio-ecological structure that leads to a bioeconomy. We argue that there is a need to configure a governance system, i.e., a new institutional arrangement (institutional infrastructure) that creates disequilibrium in the system by placing science, technology, and innovation, civil society, and a territorial agenda with a bio prospective at its core to set the pathway for a bioeconomy. Civil society is not adequately represented on the map of stakeholders, and their role in the bioeconomy remains unknown. Successive research is needed to better understand the importance, influence, and interests of stakeholders, including civil society. There seems to be a sense of timidity or marginality in the inclusion of civil society as stakeholders, making it challenging for the region to achieve a transition to a bioeconomy.

It is evident that stakeholders show a complex interaction based on the framework with emerging categories of importance, influence, and interest. These interactions show little cohesiveness and cooperation that can result in innovation in accordance with the long-term vision needed for a bioeconomy. Further research needs to address the changing nature of the importance, influence, and interest of stakeholders, taking into account their political will and commitment to bioeconomy transition.

Finally, we observe that the Department of Caldas has formulated initiatives, developed policies, and constructed institutions and organisations in the region. The results obtained in this study can be generalised to other regions in Colombia and other countries with similar circumstances. Therefore, comparative analysis is important for understanding the development of territorial agenda and the integration of stakeholders, including the genuine incorporation and participation of civil society. These studies can potentially shed light on the current dynamic structure of stakeholders and thereby enhance innovation processes towards a bioeconomy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.H.G.E., J.C.G.T. and A.O.V.R.; methodology, C.H.G.E., J.C.G.T. and A.O.V.R.; software, J.C.G.T.; validation, C.H.G.E., J.C.G.T. and A.O.V.R.; formal analysis, C.H.G.E., J.C.G.T. and A.O.V.R.; investigation, C.H.G.E., J.C.G.T. and A.O.V.R.; resources, C.H.G.E. and J.C.G.T.; data curation, J.C.G.T.; writing—original draft preparation C.H.G.E., J.C.G.T. and A.O.V.R.; writing—review and editing, C.H.G.E., J.C.G.T. and A.O.V.R.; visualisation C.H.G.E., J.C.G.T. and A.O.V.R.; supervision, C.H.G.E.; project administration, C.H.G.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MINCIENCIAS (Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación) and University of Manizales, grant number 903.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy restrictions research data cannot be shared.

Acknowledgments

The authors wan t to thank Paula Andrea Salazar Sánchez, Ana María Durango Gómez, and Oscar Fernando Gómez Morales for their invaluable collaboration in data collection and reaching out participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Issues that stop transfer and transition to a bioeconomy in the Department of Caldas.

Table A1.

Issues that stop transfer and transition to a bioeconomy in the Department of Caldas.

| Issues That Stop the Transfer of Research to a Bioeconomy | Issues That Stop the Transition of Biotechnology to a Bioeconomy | Stakeholders |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient investment in research, development and innovation (R + D + I) components | The national strategy for the sectoral bioeconomy has been insufficient to advance in its adoption | Public sector Business sector Research institutions and organisations |

| There is a lack of efficiency in technology transfer mechanisms, such as incubators, technology parks, or public–private collaboration agreements | Public and private organisations do not have operational structures that adapt to a new bioeconomic model | Public sector Business sector Entrepreneurship organisations |

| There are no clear incentives, such as subsidies, tax breaks, or market access, especially small- and medium-sized ones, to implement innovations that come from biotechnology research | There are few actors with great power that control economic resources and political decisions | Public sector Some actors in the business sector Research institutions and organisations |

| Uncertainty about the risks associated with the implementation of new technologies stops the transfer of research results into practice | Resistance to risk-taking and innovation | Business sector Entrepreneurs Entrepreneurship organisations |

| The lack of continuing education programmes and low technical expertise in key areas of the bioeconomy limit society’s ability to adopt innovations | Lack of shared visions between organisations and the public and private sectors | Public sector Business sector |

| Many companies, especially smaller ones, may not have the resources to cover the costs of adapting to the new technologies investigated | Limited coordination and alignment among stakeholders | Public sector Business sector |

| The prevalence of a short-term approach based on quick outcomes rather than long-term sustainable development | Business sector Entrepreneurs Entrepreneurship organisations |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Summary of comparative studies.

Table A2.

Summary of comparative studies.

| Country | Level of Analysis | Sector | IS | Development Block | Institutional Infrastructure | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland | National | Wood sector | National | Research organisation, industries, and government agencies | National bioeconomy strategy and implementation | [10,31,32,36,63] |

| Sweden | National | Forest-based products, agriculture, food sector | Regional | Collaboration between biotechnology companies: high-tech | Regional strategies and policies and implementation | |

| Colombia | Local | Biotechnology sector (agriculture, food processing, and coffee production) | Technological | Research based collaboration among public (gov. agencies) and private (food companies, agriculture) organisations | Departmental and municipal approaches aligned with national bioeconomy strategy and policies. However, formal and informal interactions based on the importance, influence, and interests of stakeholders | |

| Thailand | National | Agriculture (cassava and sugar cane) | National | Local knowledge and biodiversity conservation | National bioeconomy strategy and implementation | |

| Rwanda | National | Sustainable use of woody biomass: firewood and charcoal in urban and rural areas | National | Wood and charcoal supply chain | National bioeconomy strategy and implementation |

Appendix C

Figure A1.

Key factors for bioeconomy development.

Figure A1.

Key factors for bioeconomy development.

References

- European Commission. Innovating for Sustainable Growth. A Bioeconomy for Europe. 2012. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1f0d8515-8dc0-4435-ba53-9570e47dbd51 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- European Commission. A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection Between Economy, Society and the Environment Updated Bioeconomy Strategy. 2018. Available online: http://europa.eu (accessed on 1 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Sołtysik, M.; Urbaniec, M.; Wojnarowska, M. Innovation for sustainable entrepreneurship: Empirical evidence from the bioeconomy sector in poland. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawel, E.; Pannicke, N.; Hagemann, N. A path transition towards a bioeconomy-The crucial role of sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, U.; Brunori, G.; Chiaramonti, D.; Galanakis, C.; Hellweg, S.; Matthews, R.; Panoutsou, C. Future Transitions for the Bioeconomy Towards Sustainable Development and a Climate-Neutral Economy Knowledge Synthesis Final Report. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc (accessed on 7 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Robert, N.; Giuntoli, J.; Araujo, R.; Avraamides, M.; Balzi, E.; Barredo, J.I.; Baruth, B.; Becker, W.; Borzacchiello, M.T.; Bulgheroni, C.; et al. Development of a bioeconomy monitoring framework for the European Union: An integrative and collaborative approach. New Biotechnol. 2020, 59, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giampietro, M. On the Circular Bioeconomy and Decoupling: Implications for Sustainable Growth. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 162, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottinger, A.; Ladu, L.; Quitzow, R. Studying the transition towards a circular bioeconomy—A systematic literature review on transition studies and existing barriers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottausci, S.; Midence, R.; Serrano-Bernardo, F.; Bonoli, A. Organic Waste Management and Circular Bioeconomy: A Literature Review Comparison between Latin America and the European Union. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Börner, J.; Förster, J.J.; von Braun, J. Governance of the bioeconomy: A global comparative study of national bioeconomy strategies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, K.; Tyfield, D. Theorizing the Bioeconomy: Biovalue, Biocapital, Bioeconomics or … What? Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2013, 38, 299–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanzó Guzmán, A.; Centeno, J.P.; Pinzón Rojas, C.M.; Rojas Jiménez, H.H. Is bioeconomic potential shared? An assessment of policy expectations at the regional level in Colombia. Innov. Dev. 2023, 13, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wydra, S. Value chains for industrial biotechnology in the bioeconomy-innovation system analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvold, G.B.; Moss, S.M.; Hodgson, A.; Maxon, M.E. Understanding the U.S. bioeconomy: A new definition and landscape. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, S.; Kumar, A.N.; Sravan, J.S.; Chatterjee, S.; Sarkar, O.; Mohan, S.V. Food waste biorefinery: Sustainable strategy for circular bioeconomy. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 248, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlgemuth, R.; Twardowski, T.; Aguilar, A. Bioeconomy moving forward step by step—A global journey. New Biotechnol. 2021, 61, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giurca, A.; Befort, N. Deconstructing substitution narratives: The case of bioeconomy innovations from the forest-based sector. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 207, 107753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levidow, L.; Birch, K.; Papaioannou, T. EU agri-innovation policy: Two contending visions of the bio-economy. Crit. Policy Stud. 2012, 6, 40–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levidow, L.; Birch, K.; Papaioannou, T. Divergent Paradigms of European Agro-Food Innovation: The Knowledge-Based Bio-Economy (KBBE) as an R&D Agenda. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2013, 38, 94–125. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R. National Innovation Systems: A Comparative Analysis; Oxord University Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Edquist, C. Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions and Organizations; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hlangwani, E.; Mpye, K.L.; Matsuro, L.; Dlamini, B. The use of technological innovation in bio-based industries to foster growth in the bioeconomy: A South African perspective. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2023, 19, 2200300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paşnicu, D.; Ghenţa, M.; Matei, A. Transition to bioeconomy: Perceptions and behaviors in Central and Eastern Europe. Amfiteatru Econ. 2019, 21, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Rotmans, J. The practice of transition management: Examples and lessons from four distinct cases. Futures 2010, 42, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamborg, C.; Anker, H.T.; Sandøe, P. Ethical and legal challenges in bioenergy governance: Coping with value disagreement and regulatory complexity. Energy Policy 2014, 69, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frow, E.; Ingram, D.; Powell, W.; Steer, D.; Vogel, J.; Yearley, S. The politics of plants. Food Secur. 2009, 1, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, F.; Smith, A. Restructuring energy systems for sustainability? Energy transition policy in the Netherlands. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4093–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, R.; Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pistorius, T. Discursive regime dynamics in the Dutch energy transition. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2014, 13, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberg, J.; Söderholm, P.; Hellsmark, H.; Nordqvist, S. Crossing the biorefinery valley of death? Actor roles and networks in overcoming barriers to a sustainability transition. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 27, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguenin, A.; Jeannerat, H. Creating change through pilot and demonstration projects: Towards a valuation policy approach. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, R.; Rotmans, J. Transition governance towards a bioeconomy: A comparison of Finland and The Netherlands. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Giurca, A.; Brockhaus, M.; Toppinen, A. Actors and politics in Finland’s forest-based bioeconomy network. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.; Hansen, T.; Hellsmark, H. Innovation in the bioeconomy–dynamics of biorefinery innovation networks. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 30, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellsmark, H.; Mossberg, J.; Söderholm, P.; Frishammar, J. Innovation system strengths and weaknesses in progressing sustainable technology: The case of Swedish biorefinery development. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller KJ, F.; Klerkx, L.; Poortvliet, P.M.; Godek, W. Exploring barriers to the agroecological transition in Nicaragua: A Technological Innovation Systems Approach. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 44, 88–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, F.X.; Canales, N.; Fielding, M.; Gladkykh, G.; Aung, M.T.; Bailis, R.; Ogeya, M.; Olsson, O. A comparative analysis of bioeconomy visions and pathways based on stakeholder dialogues in Colombia, Rwanda, Sweden, and Thailand. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2022, 24, 680–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Hernández, V.; Schanz, H. Agency in actor networks: Who is governing transitions towards a bioeconomy? The case of Colombia. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergek, A.; Jacobsson, S.; Carlsson, B.; Lindmark, S.; Rickne, A. Analyzing the functional dynamics of technological innovation systems: A scheme of analysis. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, B.; Stankiewicz, R. On the Nature, Function and Composition of Technological Systems. J. Evol. Econ. 1991, 1, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological Transitions and System Innovations: A Co-Evolutionary and Socio-Technical Analysis; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Devaney, L.; Henchion, M. Consensus, caveats and conditions: International learnings for bioeconomy development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1400–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekkert, M.P.; Suurs RA, A.; Negro, S.O.; Kuhlmann, S.; Smits, R.E.H.M. Functions of innovation systems: A new approach for analysing technological change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2007, 74, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, L.; Díaz López, F.J. Comparing systems approaches to innovation and technological change for sustainable and competitive economies: An explorative study into conceptual commonalities, differences and complementarities. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, K.; Hermans, F. Innovation in the bioeconomy: Perspectives of entrepreneurs on relevant framework conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilden, R.; Gudergan, S.P. The impact of dynamic capabilities on operational marketing and technological capabilities: Investigating the role of environmental turbulence. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundvall, B. National Systems of Innovation: Towards a Theorem of Innovation and Interactive Learning; Pinter: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, B. Technological System and Economic Performance: A Case of Factory Automation; Kluwer Academic: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, J.A.; O’Reilly, P. Macro, meso and micro perspectives of technology transfer. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Barth, T.D.; Campbell, D.F. The Quintuple Helix innovation model: Global warming as a challenge and driver for innovation. J. Innov. Entrep. 2012, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, E.; Williams, M.D.; Davies, G.H. Recipes for success: Conditions for knowledge transfer across open innovation ecosystems. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C.; Chen, M.H. Comparing approaches to systems of innovation: The knowledge perspective. Technol. Soc. 2004, 26, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploum, L.; Blok, V.; Lans, T.; Omta, O. Exploring the relation between individual moral antecedents and entrepreneurial opportunity recognition for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1582–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, C.; González-Moreno, Á.; Sáez-Martínez, F.J. Eco-innovation: Insights from a literature review. Innov. Manag. Policy Pract. 2015, 17, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, V.; Rosenbusch, N.; Bausch, A. Success Patterns of Exploratory and Exploitative Innovation: A Meta-Analysis of the Influence of Institutional Factors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1606–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitshaki, R.; Kropp, F. Motivations and Opportunity Recognition of Social Entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddris, F. Innovation Capability: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Interdiscip. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 11, 235–260. Available online: http://www.informingscience.org/Publications/3571 (accessed on 10 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mision de Sabios por Caldas. MISIÓN DE SABIOS POR CALDAS: Equitativa, Productiva y Sostenible. Conocimiento Para El Desarrollo. 2020. Available online: https://www.ucaldas.edu.co/portal/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/LIBRO-mpazOEI.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Biotechnology Cluster. Tema: Primera Plenaria Cluster del Conocimiento en Biotecnología; Cluster de Biotecnología de Caldas: Manizales, Colombia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; Knight, P. Why interviews? In Interviewing for Social Scientists: An Introductory Resource with Examples; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1999; pp. 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Frith, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: The framework approach. Nurse Res. 2011, 18, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggs-Rapport, F. ‘Best research practice’: In pursuit of methodological rigour. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 35, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillitsch, M.; Trippl, M. Innovation Policies and New Regional Growth Paths. In Innovation Systems, Policy and Management; Niosi, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lühmann, M. Whose European bioeconomy? Relations of forces in the shaping of an updated EU bioeconomy strategy. Environ. Dev. 2020, 35, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezama, A.; Ingrao, C.; O’Keeffe, S.; Thrän, D. Resources, collaborators, and neighbors: The three-pronged challenge in the implementation of bioeconomy regions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksen, A.; Jakobsen, S.E.; Njøs, R.; Normann, R. Regional industrial restructuring resulting from individual and system agency. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 32, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labory, S.; Bianchi, P. Regional industrial policy in times of big disruption: Building dynamic capabilities in regions. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 1829–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, S.; Díaz, M.; Enciso, K.; Charry, A.; Triana, N.; Mena, M.; Urrea-Benítez, J.L.; Gallo Caro, I.; van der Hoek, R. The impact of COVID-19 on the sustainable intensification of forage-based beef and dairy value chains in Colombia: A blessing and a curse. Trop. Grassl.-Forrajes Trop. 2022, 10, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Vredenburg, H. The challenges of innovating for sustainable development. Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos Lima, M.G. Corporate power in the bioeconomy transition: The policies and politics of conservative ecological modernization in Brazil. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R. Relatedness as driver of regional diversification: A research agenda. Reg. Stud. 2017, 51, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, M.; Papaluca, O.; Sasso, P. The System Thinking Perspective in the Open-Innovation research: A systematic review. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchaut, B.; de Vriend, H.; Asveld, L. Uncertainties and uncertain risks of emerging biotechnology applications: A social learning workshop for stakeholder communication. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 946526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkus, A.; Lüdtke, J. A systemic evaluation framework for a multi-actor, forest-based bioeconomy governance process: The German Charter for Wood 2.0 as a case study. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 113, 102113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, S.R. Innovation Perspectives for the Bioeconomy of Non-Timber Forest Products in Brazil. Forests 2022, 13, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, M. Inter-sectoral determinants of forest policy: The power of deforesting actors in post-2012 Brazil. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 77, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackfort, S. Unlocking sustainability? The power of corporate lock-ins and how they shape digital agriculture in Germany. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 101, 103065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thazin Aung, M.; Nguyen, H.; Denduang, B. Power and Influence in the Development of Thailand’s Bioeconomy. A Critical Stakeholder Analysis; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Backhouse, M.; Lehmann, R. New ‘renewable’ frontiers: Contested palm oil plantations and wind energy projects in Brazil and Mexico. J. Land Use Sci. 2020, 15, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larner, W.; Walters, W. Global Governmentality. Governing International Spaces; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).