Sustainable Rural Healthcare Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability Innovation in Rural Health

2.2. Health Entrepreneurship in Rural Areas

2.3. Frugal Entrepreneurship

2.4. Family Entrepreneurship

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Serbian Health System: A Context for the Case of Rural Health Entrepreneurship

4.2. Case Analysis: Rural Health Entrepreneurs in Serbia

5. Discussion and Future Research Direction

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial and Political Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Regulation | Years Published/ Modified | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare Law | 2019 | This law regulates the organization and provision of healthcare services and all aspects of healthcare in the Republic of Serbia. It aims to ensure the standard of adequate healthcare for all citizens in the Republic of Serbia and regulates the rights and obligations of healthcare workers in the performance of their work, as well as the rights of patients. With regard to private practice, founders within the meaning of this law may be one of the following: unemployed medical personnel or medical personnel receiving a retirement pension. The law regulates that a private practice can be established as: (1) Medical practice (general, specialist, and specialty); (2) Dental practice (general and specialist); (3) Polyclinic; (4) Laboratory (for biochemistry with hematology and immunochemistry, microbiology with virology, pathohistology with cytology); (5) Pharmacy with its own practice; (6) Clinic (for healthcare and rehabilitation); (7) Laboratory for dental technology. The law also provides that private practices may not engage in activities related to emergency medical assistance, preparation of blood and blood components, removal, storage, and transplantation of organs, cells, and tissues as parts of the human body, preparation of serum and vaccines, patho-anatomical autopsy and forensic medicine, and public healthcare. |

| The Law on Health Documentation and Records in the Field of Health | 2014, 2015, 2017, 2019 | This law regulates the work of health institutions in public ownership as well as private practice. The law itself primarily regulates: (1) the obligation to maintain medical records for each patient, that is, the user of health services—diagnoses, therapies, treatments, and other relevant data; (2) storage and access to medical documentation, referring to the method of storage and the terms of storage of the documentation, as well as the access of authorized persons and patients to that documentation; (3) the obligation to protect the personal data of patients; (4) the method of keeping records of medical services provided to patients; (5) the use of electronic documentation and records; and (6) standards and procedures for archiving medical records. |

| The Law on Medical Devices | 2017 | The Law on Medical Devices is another law that can affect private practice. Namely, this law primarily regulates the conditions for the production and circulation of medical devices, i.e., their placing on the market and use in the RS, clinical trials of medical devices, monitoring of medical devices on the market, and other issues of importance for medical devices. When it comes to the impact of this law on private practice, it primarily refers to the following: (1) some medical devices used in treatment require registration, i.e., approval for use by competent authorities; (2) in order to be used adequately and serve their purpose, medical devices must meet certain standards of quality, safety, and efficiency, which is also regulated by this law; (3) import, distribution, use, and maintenance of medical devices; and (4) the law regulates the keeping of records on the use of medical devices, the monitoring of potential problems, and the process of informing the competent authorities about them. |

| The Labor Law | 2005, 2005, 2009, 2013, 2014, 2017, 2018 | The Labor Law is an act that regulates the employment relationship in the RS. When it comes to private practice, the following are important and are regulated by this act: (1) employment contract; (2) working hours; (3) compensation for work; (4) protection at work; (5) termination of employment; and (6) social rights. This act also contains information on taxes and contributions to wages. |

| Law on Protection of Personal Data | 2018 | This act regulates the procedure for the collection, processing, and protection of personal data of citizens. In healthcare, both in public and private practice, it is characteristic to collect a large volume of sensitive personal data about patients. For this reason, this law regulates the following, which refers to private practice: (1) consent of patients before collection and processing of personal data; (2) collection of data only to the extent necessary for the provision of medical services; (3) security, transfer, and storage of data; (4) in accordance with this Law and the Rulebook on Personal Data Protection, private practices are obliged to inform patients about the methods and reasons for processing their data. |

| Law on the registration procedure in the Agency for Economic Registers | 2011, 2014, 2019, 2021 | The registration of health institutions is managed by the Agency for Economic Registration. The Law on the Registration Procedure in the Business Register Agency regulates the registration procedure of business companies and entrepreneurs, as well as the conditions under which registration may be invalidated. In addition, the procedure for registering a private healthcare practice is regulated by the Rulebook in terms of the detailed content of the Register of Healthcare Institutions and the documentation required for registration. |

| The Law on Business Companies | On the bodies of health institutions in private ownership, status changes, changes in legal form, and the cessation of existence are areas where the regulations governing the legal status of companies are applied accordingly. | |

| The Law on Radiation and Nuclear Safety and Security | 2018, 2019 | This act has an impact on those medical practices that use ionizing radiation (X-ray machines, CT scanners, and others), that is, nuclear materials, in diagnostic and therapeutic practices. Here are prescribed strategies that must be followed in terms of protection and safety, but also standards that health institutions, which work in practices where radiation and nuclear materials are present, must adhere to. |

| Rulebook on closer conditions for the performance of healthcare activities in healthcare institutions and other forms of healthcare services | 2006, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2018, 2022, 2023 | This rulebook regulates the detailed conditions that must be met by health institutions of the public sector and private practice in terms of personnel, equipment, space, and medicines that are necessary for the smooth performance of health activities. |

| Rulebook on healthcare quality indicators and quality control of professional work | 2021 | It regulates the internal and external quality control of health institutions and the private sector, as well as the work of doctors in them. |

| Rulebook on forms and content of forms for maintaining health documentation, records, reports, registers, and electronic medical file | 2016, 2019 | This rulebook clearly defines the forms and their content that are used for maintaining health documentation and electronic health files. |

| Rulebook on the detailed content of the Register of Health Institutions and the documentation required for registration | 2019 | This rulebook clearly regulates the content and application forms for registration in the Register, as well as the documentation that must be submitted for registration. The documentation that, in accordance with this regulation, must be submitted for private practice registration is as follows: (1) act of establishment; (2) statute; (3) decision of the competent ministry; (4) decision on the appointment of directors and other persons authorized for representation; (5) proof of the identity of the founder; (6) proof of the identity of the director and other persons authorized for representation; (7) decision of the founder on the establishment of a branch or organizational unit outside the headquarters of the health institution (if not established by statute); (8) the director’s decision determining the weekly work schedule and the beginning and end of working hours in the health institution. This rulebook regulates the issue of the name of the health organization, the registration of the name, and the registration of status changes and changes in the name of health organizations. |

Appendix B

| Institution | Description of the Financing Conditions |

|---|---|

| Fund for the Development of the Republic of Serbia | The Development Fund of the Republic of Serbia is one of the possible sources of funding for private practice. The Development Fund offers: (1) investment loans; (2) loans for fixed and current assets; and (3) loans for beginners and young people. When it comes to investment loans, they are intended for the purchase of equipment, machines, plants, construction, or business premises. For legal entities, loan amounts range from RSD 1,000,000 to RSD 250,000,000, with a repayment period of 10 years and a grace period of one year. When it comes to entrepreneurs, the repayment period is 8 years with a grace period of one year. The loan amount in this case depends on the creditworthiness of the loan seeker. Loans for fixed and current assets are intended to finance current obligations in the course of business. Loans for beginners and young people. Funds can be obtained to the amount of 30% of the investment value, that is, 40%, for those entities that operate in the territory of local self-government units that belong to the third and fourth categories of development. The amount that can be obtained ranges from RSD 400,000 to RSD 6,000,000. |

| National Employment Service | The funds that can be obtained from the NES are modest, but this service certainly appears to be one of the potential sources of funding. The National Employment Service gives the opportunity to receive RSD 300,000 for self-employment for unemployed doctors when it comes to private practice, or RSD 330,000 if the doctor has a disability. The NES regulations clearly stipulate the documents and conditions for obtaining these funds. |

| Bank Loans | In the Republic of Serbia, in total, there are 20 banks in operation. All of them offer loans for entrepreneurs and legal entities. Bank interest rates and conditions differ, but not by much. For young doctors who want to develop a private practice, there are loans from private banks, which are realized in cooperation with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. This loan can be used for investments and working capital, but it is necessary to operate as an entrepreneur or a legal entity for 15 months before applying for the loan. Of course, most banks also offer loans for starting a business, but in order to secure larger amounts, a mortgage or some other form of guarantee is necessary. |

| EU projects and funds | Those doctors who want to engage in private practice or have already started but need additional funds must follow the tenders for the use of funds for the implementation of projects, which are announced by the EU. Participating in one of the projects when they are announced, which cover the field of healthcare, allows this institution to obtain significant equipment that they use in the process of project implementation but that they can also keep after the project implementation for the performance of their activities. It should also be mentioned that loans given out through the fund for the development of the Republic of Serbia are also in many cases co-financed or fully financed by the EU. |

Appendix C

| Type of Document | Title and Year | The Connection Between Healthcare Entrepreneurship and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Strategy | National Strategy for Sustainable Development (2007–2017): Adopted in 2008, Pending Update | Within this strategy, clear goals and action plans for achieving those goals were defined. Through support for innovation, investments, professional development, and improved education, as well as financial support for the private sector, it was possible to contribute to the strengthening of health entrepreneurship. |

| Energy Development Strategy of the Republic of Serbia until 2025 with Projections until 2030 | This strategy proposes a path for market restructuring and modernization of the energy sector in the Republic of Serbia. Besides reducing costs, this strategy can have an impact on improving the perception of private healthcare initiatives in the eyes of the community and patients. | |

| Serbia and Agenda 2030: Mapping the National Strategic Framework in Relation to Sustainable Development Goals (2020) | This document is significant as it highlights “good health” as the third goal. Within the document, specific areas are emphasized that require attention when it comes to the nation’s health, aiming to ensure the realization of defined millennium goals. Goals related to health are particularly relevant to the healthcare entrepreneurship sector, with the purpose of achieving universal access to basic health services, improving the health of children and mothers, combating infectious diseases, and strengthening the country’s healthcare system. | |

| Strategy for Prevention and Control of Chronic Non-communicable Diseases + Action Plan until 2018 | This strategy deals with cardiovascular diseases, malignant tumors, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and musculoskeletal system diseases (excluding injuries), as these non-communicable diseases have been a significant burden on the health profile of Serbia for decades. They share common risk factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, improper diet, and physical inactivity) and socio-economic determinants. This strategy guides the work of healthcare institutions in the Republic of Serbia, both in the public and private sectors, particularly concerning chronic non-communicable diseases, with the aim of improving the public health of the nation. | |

| Strategy for the Development of Mental Health 2007–2017 | This strategy provided guidelines for all healthcare institutions to improve the mental health of the nation and thereby achieve the defined Millennium Development Goals for sustainable development. | |

| Drug Abuse Prevention Strategy for the Period 2014–2021 | This strategic document aligns with the EU Drug Strategy (2013–2020). It clearly outlines objectives and guidelines that both the public and private sectors in the healthcare field must adhere to in this area. The goals set in the document are to be pursued collectively by these sectors in accordance with the overarching strategy to combat drug-related issues in the specified timeframe. | |

| Strategy for Encouraging Birth Rates 2018 | This strategy clearly outlines issues and defines goals aimed at promoting birth rates in the Republic of Serbia, addressing infertility and similar concerns. The provisions of this strategy apply to both public and private healthcare institutions. | |

| Action plan | Action Plan for the Implementation of the National Sustainable Development Strategy for the Period 2009–2017 | This action plan defined measures and activities to be undertaken to achieve the sustainable development goals outlined in the strategy. It also specified the responsible institutions for implementation and the resources required for goal realization. Within this action plan, measures and activities related to the healthcare sector and health were also outlined. |

| Action Plan for Drug Abuse Prevention for the Period 2014–2021 | This accompanying document is a key component, clearly illustrating the goals, institutions, measures to be taken, and financing system for achieving the objectives and implementing actions in line with the previously mentioned strategy. | |

| Law | Environmental Protection Law (2011) | This law, among other things, emphasizes the crucial role of institutions in the field of health entrepreneurship in raising awareness about the importance of environmental protection. Furthermore, it regulates the use and protection of goods of general interest in all aspects of their values, including the health aspect (SDG 6, 13, 15, 16). |

| Nature Conservation Law (2016) | Natural resources play a crucial role in initiating and developing health entrepreneurship. The climate characteristics of a particular area, water quality, and sources of thermal and mineral waters contribute to the development of health entrepreneurship. Untouched nature is a characteristic of rural areas that, from this perspective, is favorable for entrepreneurial initiatives in the field of healthcare (SDG 6, 13, 14, 15). | |

| Waste Management Law (2016) | This law, among other things, regulates the concept of medical waste and the manner of its disposal. The law is in line with the 12th UN Sustainable Development Goal. Every institution in the field of health entrepreneurship must dispose of medical waste in accordance with the legally prescribed procedures. | |

| Law on Protection from Ionizing Radiation and Nuclear Safety (2009) | In some private healthcare facilities covered by this research, diagnostic procedures involving devices emitting radiation are conducted. This law regulates the rule that individuals qualified for working with sources of ionizing radiation must do so, and they must be provided with appropriate protection and undergo regular health check-ups. (SDG 3) | |

| Environmental Impact Assessment Law (2009) | The administrative procedure for opening a private enterprise in the healthcare sector, like any business in any other field, is subject to an assessment of the environmental impact, as regulated by this law (SDG 6, 7, 12–15). | |

| Social Entrepreneurship Law (Integrating Multiple Objectives) | Social entrepreneurship, among other things, is implemented through the provision of services in the healthcare sector. The manner of realization of this form of social entrepreneurship, entities involved, objectives, and beneficiaries are regulated by this law (SDG 1, 3, 5, 10, 16). |

Appendix D. Interview Questions (Semi-Structured Interview)

- Please state your legal form, starting year, number of employees, whether employees are privately related to you, and the nature of health services provided.

- Please describe the entrepreneurial opportunity and how your services are covering local (rural) needs (the motivation and novelty of establishing the practice in the rural area).

- Can you please describe how are you creating and providing services and how accessible they are (especially compared to the competition; innovative aspects; uninterrupted service to citizens; care for vulnerable social groups; quality of services; and problems in providing the services)?

- Legal, financial, and policy environment (legal framework; financial instruments available; entrepreneurship policy; health fund relations; problems) details.

- Relevance of Agenda 2030 pertaining to economic, social, and environmental sustainability (ensuring universal access to healthcare, the response to global health threats such as more frequent and intense natural disasters, humanitarian crises and forced displacement because of spiraling conflict, violent extremism, and terrorism; maternal, newborn, and child health and reproductive health; environmentally sound management of healthcare waste; protection of labor rights and environmental and health standards in accordance with international standards).

References

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Innovation: Categories and Interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. Not All Wine Businesses Are the Same: Examining the Impact of Winery Business Model Extensions on the Size of Its Core Business. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punnakitikashem, P.; Hallinger, P. Bibliometric Review of the Knowledge Base on Healthcare Management for Sustainability, 1994–2018. Sustainability 2019, 12, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehoux, P.; Roncarolo, F.; Rocha Oliveira, R.; Pacifico Silva, H. Medical Innovation and the Sustainability of Health Systems: A Historical Perspective on Technological Change in Health. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2016, 29, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004, 82, 581–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Bate, P.; Macfarlane, F.; Kyriakidou, O. Diffusion of Innovations in Health Service Organisations: A Systematic Literature Review; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, J.; Marks, D.; Taylor, N. Harnessing Implementation Science to Improve Care Quality and Patient Safety: A Systematic Review of Targeted Literature. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2014, 26, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, E.; Luke, D.; Calhoun, A.; McMillen, C.; Brownson, R.; McCrary, S.; Padek, M. Sustainability of Evidence-Based Healthcare: Research Agenda, Methodological Advances, and Infrastructure Support. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjӕrgård, B.; Land, B.; Bransholm Pedersen, K. Health and Sustainability. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Moors, E.H. Caring for Healthcare Entrepreneurs—Towards Successful Entrepreneurial Strategies for Sustainable Innovations in Dutch Healthcare. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2013, 80, 1360–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrari, A.; Sandhu, P.; Morra, D.; McClennan, S.; Freeland, A. Creating a Healthcare Entrepreneurship Teaching Program for Medical Students. J. Reg. Med. Campuses 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Svensson, G.; Wood, G. Assessing Corporate Planning of Future Sustainability Initiatives in Private Healthcare Organizations. Eval. Program Plan. 2020, 83, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grazier, K.L.; Metzler, B. Health Care Entrepreneurship: Financing Innovation. J. Health Hum. Serv. Adm. 2006, 28, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sherman, J.D.; Thiel, C.; MacNeill, A.; Eckelman, M.J.; Dubrow, R.; Hopf, H.; Lagasse, R.; Bialowitz, J.; Costello, A.; Forbes, M. The Green Print: Advancement of Environmental Sustainability in Healthcare. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kosanović, R.; Andjelski, H. Centralization and Decentralization Processes in the Health Care System in Serbia (1990–2017). Zdr. Zaštita 2017, 46, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacevic, M.; Milicevic, M.S.; Vasic, M.; Horozovic, V.; Milicevic, M.; Milic, N. The Relationship between Dual Practice, Intention to Work Abroad and Job Satisfaction: A Population-Based Study in the Serbian Public Healthcare Sector. Health Policy 2018, 122, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, S. To Be an Entrepreneur: Social Enterprise and Disruptive Development in Bangladesh; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 1-5017-4827-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bärnreuther, S. Disrupting Healthcare? Entrepreneurship as an “Innovative” Financing Mechanism in India’s Primary Care Sector. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 319, 115314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansera, M.; Sarkar, S. Crafting Sustainable Development Solutions: Frugal Innovations of Grassroots Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2016, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Sinha, R.; Koradia, D.; Patel, R.; Parmar, M.; Rohit, P.; Patel, H.; Patel, K.; Chand, V.S.; James, T.J. Mobilizing Grassroots’ Technological Innovations and Traditional Knowledge, Values and Institutions: Articulating Social and Ethical Capital. Futures 2003, 35, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, V.; Pineda-Escobar, M.A.; Howell, R.; Verheij, M.; Knorringa, P. Frugal Innovation and Sustainability Outcomes: Findings from a Systematic Literature Review. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 984–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V.; Ramadani, V.; Dana, L.-P.; Hoy, F.; Ferreira, J. Family Entrepreneurship and Internationalization Strategies. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2017, 27, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.P.; Weaver, S.; Currie, G.; Finn, R.; McDonald, R. Innovation Sustainability in Challenging Health-Care Contexts: Embedding Clinically Led Change in Routine Practice. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2012, 25, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audretsch, D.B. From the Entrepreneurial University to the University for the Entrepreneurial Society. J. Technol. Transf. 2014, 39, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åstebro, T.; Braguinsky, S.; Braunerhjelm, P.; Broström, A. Academic Entrepreneurship: The Bayh-Dole Act versus the Professor’s Privilege. ILR Rev. 2019, 72, 1094–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, I.; Müller, C.; Deimel, K. Building a Culture of Entrepreneurial Initiative in Rural Regions Based on Sustainable Development Goals: A Case Study of University of Applied Sciences–Municipality Innovation Partnership. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Urbano, D.; Cunningham, J.; Organ, D. Entrepreneurial Universities in Two European Regions: A Case Study Comparison. J. Technol. Transf. 2014, 39, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg-Yunger, Z.R.; Daar, A.S.; Singer, P.A.; Martin, D.K. Healthcare Sustainability and the Challenges of Innovation to Biopharmaceuticals in Canada. Health Policy 2008, 87, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjou, N. Frugal Innovation: The Engine of Sustainable Development. How to Achieve Better Health Care for More People at Lower Cost. In Reimagining Global Health: 30 High-Impact Innovations to Save Lives; PATH: Seattle, WA, USA, 2015; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Whyle, E.B.; Olivier, J. Models of Public–Private Engagement for Health Services Delivery and Financing in Southern Africa: A Systematic Review. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 1515–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ke, Y.; Liu, T.; Sankaran, S. Social Sustainability in Public–Private Partnership Projects: Case Study of the Northern Beaches Hospital in Sydney. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 2437–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, F.; Izbirak, G. A Stakeholder Perspective of Social Sustainability Measurement in Healthcare Supply Chain Management. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, N.; Ratten, V.; Stavroyiannis, S.; Makris, I.; Apostolopoulos, S.; Liargovas, P. Rural Health Enterprises in the EU Context: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2020, 14, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.; Prior, M.; Taylor, J. A Theory of How Rural Health Services Contribute to Community Sustainability. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1903–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, J.; Lauder, W.; Richards, H.; Sharkey, S. Dr. John Has Gone: Assessing Health Professionals’ Contribution to Remote Rural Community Sustainability in the UK. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.; Kilpatrick, S. Are Rural Health Professionals Also Social Entrepreneurs? Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearns, R.A. Going It Alone: Place, Identity and Community Resistance to Health Reforms in Hokianga, New Zealand. In Putting Health into Place: Landscape, Identity and Wellbeing; Syracuse University Press: Syracuse, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 226–247. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, F. The New Public Health: An Australian Perspective; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marković-Petrović, G.D. Akreditacija Zdravstvenih Ustanova Kao Doprinosni Faktor Kvalitetu Rada u Bolničkoj Zaštiti. Ph.D. Thesis, Univerzitet u Beogradu, Belgrade, Serbia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hiendl, C.; Gertler, S. Innovationen im Gesundheitswesen—Rechtliche und ökonomische Rahmenbedingungen und Potentiale: Betriebliches Gesundheitsmanagement. In Innovationen im Gesundheitswesen; Grinblat, R., Etterer, D., Plugmann, P., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022; pp. 235–248. ISBN 978-3-658-33800-8. [Google Scholar]

- McCleary, K.J.; Rivers, P.A.; Schneller, E.S. A Diagnostic Approach to Understanding Entrepreneurship in Health Care. J. Health Hum. Serv. Adm. 2006, 28, 550–577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramdorai, A.; Herstatt, C. Frugal Innovation in Healthcare: How Targeting Low-Income Markets Leads to Disruptive Innovation. Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-319-16336-9.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Brnjas, Z. Javno-Privatno Partnerstvo Kao Instrument Realizacije Infrastrukturnih Projekata. 2015. Available online: http://ebooks.ien.bg.ac.rs/36/ (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Apostolopoulos, N.; Liargovas, P.; Sklias, P.; Makris, I.; Apostolopoulos, S. Private Healthcare Entrepreneurship in a Free-Access Public Health System: What Was the Impact of COVID-19 Public Policies in Greece? J. Entrep. Public Policy 2022, 11, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Frugal Innovation: Conception, Development, Diffusion, and Outcome. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeurissen, P.; Maarse, H. Hospital Care: Private Assets for-a-Profit? In Understanding Hospitals in Changing Health Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Country Cooperation Strategy: India 2012–2017. 2012. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/161136/B4975.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Brem, A.; Wolfram, P. Research and Development from the Bottom Up-Introduction of Terminologies for New Product Development in Emerging Markets. J. Innov. Entrep. 2014, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Frugal Entrepreneurship: Resource Mobilization in Resource-constrained Environments. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2022, 31, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Billou, N. Serving the World’s Poor: Innovation at the Base of the Economic Pyramid. J. Bus. Strategy 2007, 28, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, R.K.; Hoy, F.; Poutziouris, P.Z.; Steier, L.P. Emerging Paths of Family Entrepreneurship Research. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2008, 46, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Cliff, J.E. The Pervasive Effects of Family on Entrepreneurship: Toward a Family Embeddedness Perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Harms, R.; Fink, M. Family Firm Research: Sketching a Research Field. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2011, 13, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baù, M.; Chirico, F.; Pittino, D.; Backman, M.; Klaesson, J. Roots to Grow: Family Firms and Local Embeddedness in Rural and Urban Contexts. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 360–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, D.J. The Concept of Family: An Analysis of Laypeople’s Views of Family. J. Fam. Issues 2008, 29, 1426–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlaner, L.M.; Kellermanns, F.W.; Eddleston, K.A.; Hoy, F. The Entrepreneuring Family: A New Paradigm for Family Business Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 38, pp. 1–11. ISBN 0921-898X. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, D.; Minola, T.; Bosio, G.; Cassia, L. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on University Students’ Entrepreneurial Skills: A Family Embeddedness Perspective. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinelli, C.; Fayolle, A.; Randerson, K. Family Entrepreneurship: A Developing Field. Found. Trends® Entrep. 2014, 10, 161–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmitt, J.; Muñoz, P.; Newbery, R. Poverty and the Varieties of Entrepreneurship in the Pursuit of Prosperity. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 105939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, C. Using Case Study Research as a Rigorous Form of Inquiry. Nurse Res. 2014, 21, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Long, A.; Ascent, D. World Economic Outlook; International Monetary Fund: Bretton Woods, NH, USA, 2020; Volume 177. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2021–2022; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Privatna Medicinska Praksa u Srbiji. 2012. Available online: https://www.aim.rs/privatna-medicinska-praksa-u-srbiji-2012/ (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Jović, Ž.R. Razvoj Modela Međjuzavisnosti Prodajnih Aktivnosti i Pozicioniranosti Brenda Privatnih Zdravstvenih Ustanova u Republici Srbiji. Ph.D. Thesis, Univerzitet u Beogradu, Belgrade, Serbia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Radovanović, D. Some Legal Dilemmas Regarding the Moratorium on Employment in the Public Sector. Glas. Advok. Komore Vojv. 2023, 95, 106–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petković, M.; Djedović–Nègre, D.; Lukić, J. Public-Private Partnerships: Interorganizational Design as Key Success Factor. Manag. J. Sustain. Bus. Manag. Solut. Emerg. Econ. 2015, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Markovic, V. Uvod u Zdravstveno Pravo; Singidunum University: Belgrade, Serbia, 2021; ISBN 978-86-7912-749-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jakovljevic, M. Health Expenditure Dynamics in Serbia 1995–2012. Hosp. Pharmacol. 2014, 1, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheiman, I.; Shishkin, S.; Shevsky, V. The Evolving Semashko Model of Primary Health Care: The Case of the Russian Federation. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2018, 11, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosanović, R.; Anđjelski, H. Basic Directions of Development Health Insurance in the Republic of Serbia (1922–2014). Zdr. Zaštita 2015, 44, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmelee, D.E. Whither the State in Yugoslav Health Care? Soc. Sci. Med. 1985, 21, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lameire, N.; Joffe, P.; Wiedemann, M. Healthcare Systems—An International Review: An Overview. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1999, 14, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, R.; Blümel, M.; Knieps, F.; Bärnighausen, T. Statutory Health Insurance in Germany: A Health System Shaped by 135 Years of Solidarity, Self-Governance, and Competition. Lancet 2017, 390, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, I. Uporedna Analiza Održivog Razvoja Planinskog Turizma Alpske i Dinarske Regije; Univerzitet Singidunum: Belgrade, Serbia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paunović, I.; Jovanovic, V. Sustainable Mountain Tourism in Word and Deed: A Comparative Analysis in the Macro Regions of the Alps and the Dinarides. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2019, 59, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, S.; Makris, I.; Stavroyiannis, S. Healthcare Innovation in Greece: The Views of Private Health Entrepreneurs on Implementing Innovative Plans. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastoka, J.; Petković, S.; Radicic, D. Impact of Entrepreneurship on the Quality of Public Health Sector Institutions and Policies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstic, K.; Janicijevic, K.; Timofeyev, Y.; Arsentyev, E.V.; Rosic, G.; Bolevich, S.; Reshetnikov, V.; Jakovljevic, M.B. Dynamics of Health Care Financing and Spending in Serbia in the XXI Century. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. Case Studies and Generalizability: Grounded Theory and Research in Science Education. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2000, 22, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of Evidence | Primary/Secondary Source | Number and Description |

|---|---|---|

| Interviews | Primary | 6 interviews with 2 private medical practices, 2 policlinics, and 2 with dental practices |

| Expert workshops | Secondary | 3 workshops with 4 health experts together with the 4 authors |

| Laws | Secondary | 14 laws |

| Other documents | Secondary | 2 strategies, 4 rulebooks, 1 map of national strategic framework |

| Websites | Secondary | 6 websites of the private practices interviewed |

| Serbian Healthcare before 1990 | Serbian Healthcare after 1990 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dedicated healthcare contribution and fund for employees and their families, since 1962 in different forms and names, and from 1972 onwards called “Government self-managing interest community for healthcare” as well as communal “self-governing health communities” [75] | A Bismarckian health system characteristic | Dedicated healthcare contribution and fund for employees and their families, called in different periods also “Institution of the republic for health insurance”, presently “Fund of the republic for health insurance” [75] | A Bismarckian health system characteristic |

| Government financing from the budget [76] | A Beveridge health system characteristic | Government financing from the budget [76] | A Beveridge health system characteristic |

| General ban on private practices from 1958, although older practices were allowed to continue [76] | A Semashko health system characteristic | Out-of-pocket and private health insurance for private practice, rare contracts with state health fund | A post-Semashko health system characteristic as determined in the literature [74]. |

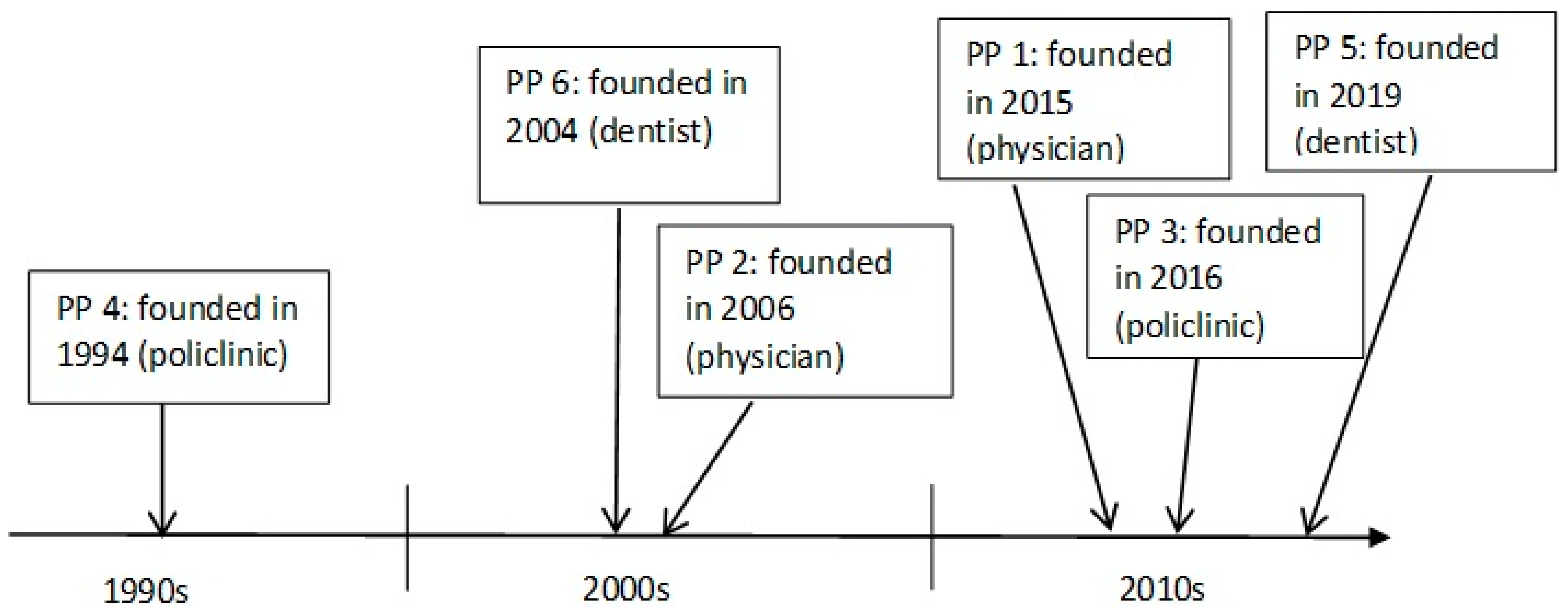

| Private Practice No. (PP No.) | Health Service Provider Type | Description of Services Offered | Year Founded |

|---|---|---|---|

| PP 1 | Physician | Neurological practice with part-time specialists of all profiles | 2015 |

| PP 2 | Physician | Pediatric practice | 2006 |

| PP 3 | Policlinic | Internal medicine, gynecology, ophthalmology, biochemistry, surgery, anesthesia | 2016 |

| PP 4 | Policlinic | Surgery, radiology, cardiology, other part-time specialists | 1994 |

| PP 5 | Dentist | Dental services | 2019 |

| PP 6 | Dentist | Dental services | 1994 |

| Private Practice No. | Sustainability-Oriented Innovation Codes |

|---|---|

| PP 1 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| PP 2 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| PP 3 |

|

| |

| PP 4 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| PP 5 |

|

| |

| |

| PP 6 |

|

| Private Practice No. | Frugal Entrepreneurship Codes |

|---|---|

| PP 1 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| PP 2 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

| Private Practice No. | Frugal Entrepreneurship Codes |

|---|---|

| PP 3 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| PP 4 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| PP 5 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| PP 6 |

|

| |

|

| Private Practice No. | Family Entrepreneurship Codes |

|---|---|

| PP 1 |

|

| |

| PP 2 |

|

| PP 3 |

|

| |

| PP 4 |

|

| |

| PP 5 |

|

| |

| |

| PP 6 |

|

| |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paunović, I.; Apostolopoulos, S.; Miljković, I.B.; Stojanović, M. Sustainable Rural Healthcare Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of Serbia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031143

Paunović I, Apostolopoulos S, Miljković IB, Stojanović M. Sustainable Rural Healthcare Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of Serbia. Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031143

Chicago/Turabian StylePaunović, Ivan, Sotiris Apostolopoulos, Ivana Božić Miljković, and Miloš Stojanović. 2024. "Sustainable Rural Healthcare Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of Serbia" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031143

APA StylePaunović, I., Apostolopoulos, S., Miljković, I. B., & Stojanović, M. (2024). Sustainable Rural Healthcare Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of Serbia. Sustainability, 16(3), 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031143