Abstract

Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) aims to swiftly adapt conventional face-to-face educational methods to alternative (typically virtual) formats during crises. The recent COVID-19 pandemic accentuated the vulnerability of traditional educational systems, revealing limitations in their ability to effectively withstand such unprecedented events, thereby exposing shortcomings in the adopted ERT strategies. The goal of this study is to discuss the establishment of resilient, sustainable, and healthy educational systems in non-crisis times, which will enable teachers and students to make a smoother and less stressful transition to Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) when necessary. A comprehensive hybrid approach, combining quantitative (interviews) and qualitative (online survey) methods has obtained data from 276 professors in 29 countries. These data have been used to identify a range of challenges related to ERT and their perceived level of difficulty. The methodological and social challenges (overshadowed by technical issues at the beginning of the crisis) identified in this research—such as the lack of personal contact or poor feedback from students—have been found to be the most demanding. From the collected insights regarding the perceived level of difficulty associated with the identified challenges, the present study aims to contribute to making higher education systems more robust in non-crisis times.

1. Introduction

In the first half of 2020, Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in most parts of the world had to close due to restrictions imposed by the SARS-CoV-2 lockdowns [1]. The teaching suddenly transitioned from traditional face-to-face teaching in physical classrooms to synchronous online learning [2]. The teaching and learning community was pushed out of the zone of the formally defined [3,4] to an unfamiliar and unpredictable environment [2]. The Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) of the 2023 Agenda is to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”, and many aspects of this objective were undermined during the pandemic [5].

Today, we can say with certainty that the pandemic represented the most extensive global experiment in remote teaching and learning [6], which motivated the conception of the term Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT). ERT is now well-defined and well-described in the scientific literature. In the following, the main characteristics of teaching under crisis circumstances based on the articles by Hodges et al. [7] and Khlaif et al. [8] are outlined:

- ERT is implemented as a fully remote teaching solution for education, delivered for the duration of a crisis and consisting of online, blended or hybrid courses.

- ERT tends to provide temporary access to education in a manner that is quick to set up and is readily available during an emergency or crisis.

- Once the crisis subsides, ERT switches to the previous way of teaching or evolves into a more resilient and improved version.

- During crises, preparation time is limited, leading to ERT being implemented with minimal or no prior preparation in the organizational, pedagogical and technical aspects.

During the deployment of ERT, both teachers and students faced unique and unprecedented challenges. To guarantee that the issues arising from these challenges can be minimized in future situations where ERT may be required again, it is crucial to identify them as useful learning opportunities. Conducting such analysis at present times allows for a comprehensive understanding of the evolving landscape—beyond the acute stage of the pandemic—enabling a more nuanced examination free from the immediacy and rush that characterized the peak of the crisis three years ago. Therefore, this work explores the perceived difficulty of the technical, methodological, pedagogical and social challenges along the crisis timeline in order to meet the objectives of the SDG4 of Agenda 2030.

Indeed, the small number of in-depth, retrospective, and generalizable analyses of the technical, methodological, pedagogical and social challenges associated with standardized solutions for a rapid transition from regular teaching to ERT have led to an important gap in the scientific literature [1,3,4,6,9,10,11]. The quality of the solutions to be developed for ERT transition and implementation will be highly dependent on a comprehensive knowledge and understanding of the challenges and the idiosyncrasies from which they emerge. In response to this need, this paper aims to address the identified gap in the literature, providing a complete exploration of the challenges and discussing a solution for a smoother transition to ERT. The paper also exhibits originality by following the topicality of challenges over the entire duration of ERT, which, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, has not been identified in prior studies. The remaining five sections of this paper describe the research phases and study results. The literature review in Section 2 explains the theoretical starting points. Section 3 defines the research goal and questions and sets the research methodology. In Section 4, the research findings are provided in the form of the experiences of teachers and students collected through interviews and surveys. Section 5 provides guidelines for establishing resilient, sustainable, and healthy higher educational systems in non-crisis times. The article ends with a conclusion.

2. Literature Review

There is a lot of operational problem-solving during crises times that motivate ERT which causes physical isolation of HEIs and other aspects of life since the situation can change from hour to hour. This is when all the members in a HEI community (i.e., students and staff) are entirely dependent on Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). Technical staff are typically overwhelmed and struggle to help all those who need assistance simultaneously and comprehensively. For this reason, the transition to ERT requires additional effort from teachers, who depend mainly on their (prior) knowledge, level of digital competencies, and even luck in finding direct helpful information and resources to effectively implement ERT. Diverse knowledge at the onset of the crisis led teachers to apply teaching approaches aligned with their own individual abilities, which often made it difficult for students to understand the suddenly changed learning environment [12]. In addition, the success of the rapid adaptation of teaching in the context of crises or paradigm shifts also depends on HEIs’ organizational preparedness, the flexibility of structures for decision support and the availability of informal communication channels [13].

It has been widely reported that during the COVID pandemic—which brought an implicit transition to ERT—even teachers with considerable experience in remote teaching faced critical difficulties and challenges [3]. These stem from the need to balance domestic responsibilities, acquire and/or upgrade missing competencies, create a learning environment, teach, generate new course content, ensure and maintain quality contact with students and, last but not least, take into account the specific needs of students [14].

A detailed literature review on the challenges of online teaching during the pandemic from the lecturers’ point of view was prepared by Na and Jung [15]. In their study, the ERT challenges are divided into seven categories, namely challenges regarding (1) managing/conducting online classes, (2) usage of online learning platforms/software, (3) teaching classes effectively, (4) interaction with students, (5) student participation and learning in class, (6) course preparation and (7) solving technical issues. This literature review (i.e., Na and Jung [15]) is based exclusively on articles published in 2020, thus representing a credible starting point for the research presented in this paper.

In the following table, we update and extend the work from Na and Jung [15] with a new review of the literature and summarize the findings on ERT challenges from studies that followed this comprehensive review and further grouped them into three categories: technical, pedagogical, and social (Table 1). This table aims to name challenges as closely as possible to the terminology used by the authors of the referenced works.

Table 1.

Technical, pedagogical, and social challenges related to ERT.

According to our literature review (see Table 1), teachers found the transition from traditional face-to-face teaching to completely remote to be the most challenging aspect [38] and most of them admitted having the feeling of being unprepared [25,30]. Several authors [4,6,16,17,19,21,25,26] highlighted that one of the common challenges was also a lack of needed ICT, not only in terms of physical resources but also in terms of operational knowledge. Namely, the minimum requirement for ERT is using a computer, speaker, microphone, and access to a high-performance internet connection. Hardware is a prerequisite for ERT, followed by access to the software, which brings the issue of having competencies to work with devices mentioned above. Early scientific studies conducted in 2020 mainly emphasize the presence of technical challenges. For example, ref. [22] reported internet access as the most encountered problem in Turkish educational institutions. This is supported by studies carried out highlighting technical challenges like the inability to access needed online tools and devices [26], lack of technological knowledge [25], and lack of digital skills and literacy [4,6,17,27,28,29]. Some of the authors [28,29] also pointed out the lack of pedagogical skills that hinder the effective adaptation of teaching during ERT.

As a pedagogical challenge, authors frequently state the need to modify teaching methods and pedagogical techniques [6,25,30,31,32,33,34]. The need is justified by the desire to improve the informational value of the subject material and inspire students. In addition to new teaching methods, lecturers had to learn and use new methods for formative assessments [23,27,30] and re-design courses for ERT [17]. Mukhtar [31] and Arja et al. [16] observed teachers’ challenges in reinventing hands-on experiences in ERT, such as finding substitutes for physical work in the laboratory and effectively teaching different practical and clinical work. Additionally, a challenge related to pedagogical shortcomings is the lack of use of cameras by students, which makes it impossible for teachers to follow students’ engagement during online sessions and adapt teaching according to the atmosphere among the participants [16]. In addition, some teachers also faced a lack of support from their HEIs, excessive workload, and long working hours [25] in adapting courses to ERT requirements and implementing the changes effectively [30].

Among the social challenges of ERT, many authors rank highly the lack of social networking, lack of human interaction between teachers and students, as well as among the latter which is manifested as a loss of motivation to study [6,16,25,26,35,36,37]. Additionally, it has been reported that students experienced a lack of physical space at home, a lack of parents’ support and difficulty collaborating with other people [35,36].

Shamir-Inbal and Blau [25] highlighted psychological problems such as loneliness and anxiety, which could be caused by physical isolation. In addition, the lack of interpersonal contact has led to unresponsiveness of the students [26]. Zizka and Probst [24] researched the students’ perception of online teaching and pointed out that students spent up to 90 min more on learning engagement due to obligatory online activities. With a uniquely prepared online learning environment and communication channels that were not coordinated with other learning units, the teachers influenced the students to extend their learning time. Students also received more assignments and had to spend more time watching videos, reading study material, and researching.

According to the literature, it was not only students who devoted more time to working within the ERT learning unit [39]. It has been found that preparing for online teaching is inherently more time-consuming (reviewing training materials, encouraging interactions, and preparing learning activities) for teachers than preparing for a face-to-face meeting with students in a physical classroom [39,40]. Cramarenco et al. [17] pointed out the increased need for organizing different support services, for example, financial support for disadvantaged students, socioemotional support, technical assistance for connectivity-related problems, remedial courses for students with lagging performance standards, etc.

This literature review on challenges associated with the introduction and implementation of ERT listed research studies tied to a specific region or country and carried out in the early phase of ERT implementation. For example, ref. [41] presents challenges in China’s educational system, which was the first one that faced with such a crisis. Looi [42] has researched challenges only in Malaysia. Ferri et al. [6] studied challenges based mainly on examples from Italy. Authors usually emphasize in conclusion the importance of exploring the challenges of teaching and learning during the entire duration of the crisis because they anticipate the possibility of different outcomes.

To sum up, this updated review of the literature has revealed a lack of studies that extensively research both teachers’ and students’ perspectives and the perceived level of difficulty of each of the challenges associated with ERT.

3. Methods

This research endeavor seeks a better understanding of the challenges in switching from traditional teaching methods to ERT. The goal of the study is to prepare guidelines for the establishment of resilient, sustainable, and healthy educational systems in non-crisis times, which will enable teachers and students to make a smoother and less stressful transition to ERT when necessary.

This study aims to address the following central research questions:

- RQ1: What challenges did students participating in ERT face in the period from March 2020 to March 2021?

- RQ2: What challenges did professors face during the implementation of ERT in the period from March 2020 to March 2021?

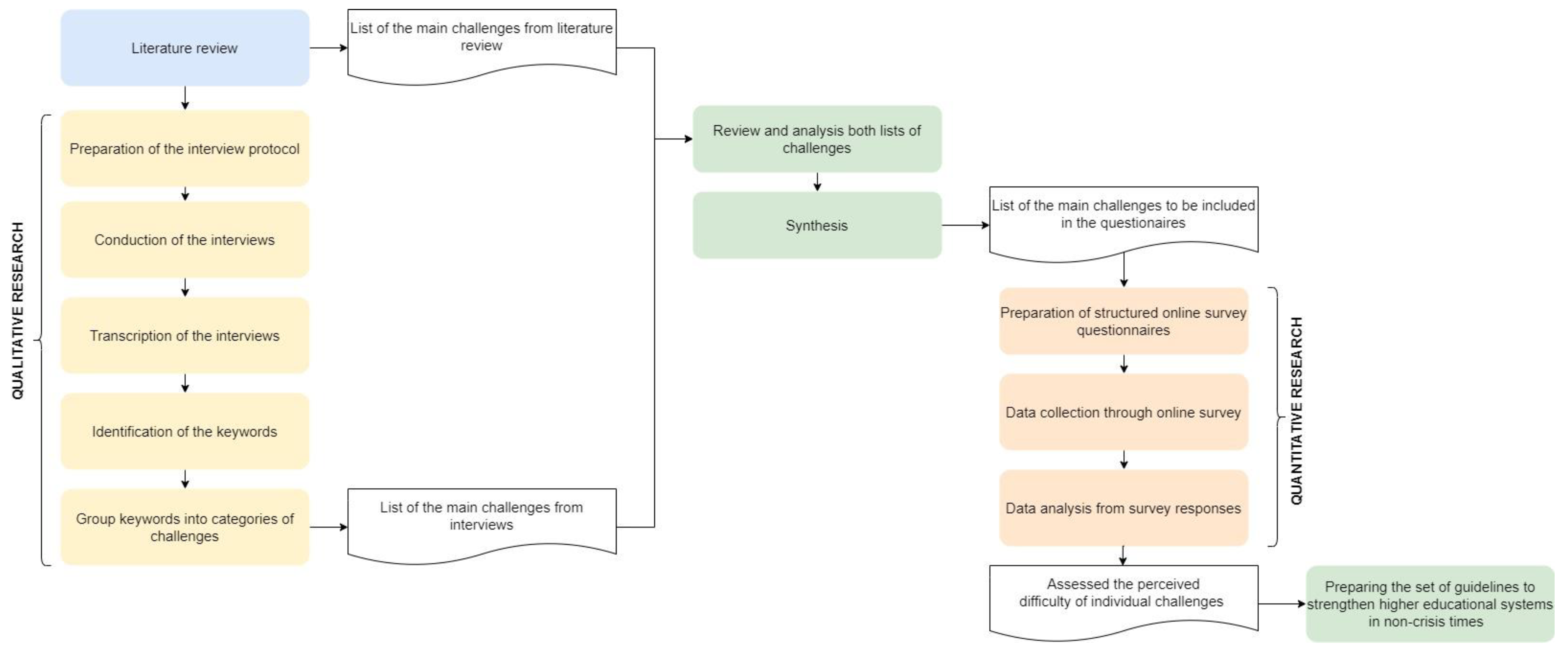

In this regard, we have selected a methodology that combines qualitative (interviews) and quantitative (survey) approaches carried out (Table 2) according to the findings and recommendations of Golicic et al. [43] (Figure 1), enabling the categorization of the identified challenges associated with rapid ERT transition (see Section 2) in different categories according to the perceived level of difficulty for both teachers and students. Indeed, preparing the list of teachers’ and students’ ERT challenges requires qualitative research, while assessing the perceived difficulty of individual challenges requires quantitative research. The adoption of a balanced approach played a crucial role in ensuring that, during the formulation of the questionnaires, deemed as a pivotal step in the research, we did not overlook any significant challenges. This approach helped us encompass the entire spectrum of challenges related to our research topic and ensured that we included questions that facilitated a comprehensive analysis of key aspects. The comprehensive list of tools is presented in Table 2, while Figure 1 provides a detailed illustration of the interconnection between individual tools and partial results.

Table 2.

Methodological tools used for the study.

Figure 1.

Methodological steps conducted in this research.

As far as the qualitative research is concerned (see Figure 1), the literature review led to an overview of the current scientific research on teachers’ and students’ challenges in practicing ERT until May 2021 by querying in Web of Science, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Wiley. The list of keywords that have been used for searching the articles related to the challenges during ERT incorporates “learning environment”, “level of engagement”, “development of teaching”, “virtual”, “online”, “extended”, “remote”, “hybrid”, “challenges” and “ERT”. Subsequently, we employed various combinations of these keywords for our search. For further analysis, we considered articles addressing the challenges faced by teachers and students due to the abrupt introduction of ERT. The list of relevant articles for this research was updated in February 2023. The obtained results have been detailed in Section 2.

For the next stage of the qualitative research (see Figure 1), two interview protocols—one for teachers and one for students—were developed with questions about the demographic data of the interviewee, the method of implementing ERT at the educational institution, the challenges of ERT, ways of coping with challenges and the examples of good practice they have experienced. The interview protocol for professors contained, in addition to demographic questions, 20 questions from the content of the research, and the questionnaire for students contained 7 questions. Professors and students have been carefully selected so that the sample covers at least 4 countries, both natural sciences and social sciences and includes individuals who have been intensively involved in the development of ERT and who have continued to work on its improvement after the end of the lockdown. We also looked for teachers who had at least five years of experience in teaching at the university level. When selecting the sample, we also included people who deliver lectures, tutorials, and laboratory sessions to gather various perspectives on the situation. We conducted the research with twelve higher education teachers of different genders, cultures, years of teaching experience, and fields employed in Italy (1), India (2), Poland (2), Slovenia (3), and Spain (4).

When selecting students for interviews, we ensured that they were at least in their second year of bachelor studies. This was carried out to include students in the sample who had experience with traditional face-to-face learning prior to the implementation of ERT. A total of 16 students from different courses and levels of study (68.75% from bachelor level and 31.25% from master level) were interviewed in Italy (1), Poland (2), Slovenia (5) and Spain (8).

Due to limitations associated with the spread of SARS-CoV-2, interviews were conducted remotely via MS Teams and Zoom in April and May 2021, one year after the imposed transition to ERT. Before interviewing, interview protocols were sent by mail to the interviewees. While interviewing, meaningful sub-questions were added according to the specific experiences the interviewee had acquired. All interviews were recorded and transcribed to facilitate analysis. The analysis of the challenges took place with open coding, which means that we did not have any predefined categories. After that, the codes were categorized into broader categories. The mentioned challenges were written out from the text of the interviews, duplication was eliminated, and the remaining challenges were classified by type of challenge.

As far as the quantitative research is concerned (see Figure 1), two structured online survey questionnaires, one for teachers and one for students, were developed based on the synthesis of the list of challenges from in-depth interviews and literature reviews to assess the perceived difficulty of the listed challenges by surveying a large number of teachers and students at an international level. The online questionnaire for teachers consisting of 44 questions was sent to 890 professors from 29 countries. A total of 276 of them (31% of those who opened the questionnaire) worldwide responded between 10 and 25 October 2021. The majority of the sample consisted of professors from Spain (23%), Slovenia (21%), Poland (18%) and Italy (10%). The remaining 28% consisted of professors from Algeria, Andorra, Austria, Bulgaria, China, Croatia, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Iran, Lithuania, Malaysia, Philippines, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Scotland, Sweden, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and the USA. A total of 110 (40%) of the respondents taught social sciences, 89 (32%) natural sciences and 77 (28%) were teachers of technical sciences. Regarding teaching experience, 30.18% of the respondents had between 10 and 20 years of experience, 29.45% had more than 20 years, 20.73% had between 1 to 5 years, 16% had between 5 to 10 years, and 3.64% had less than one year of experience. Similarly, the online survey for students was sent to 1298 students, 506 (39% of the sample) of whom completed it. The majority of the students who opened the questionnaire were from Poland (36%), Slovenia (22%), Spain (18%), and Italy (12%). Others came from 27 countries worldwide (Argentina, Australia, China, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, France, Germany, Greece, Kazakhstan, Kurdistan, Latvia, Morocco, Netherlands, Nigeria, Peru, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, Venezuela). A total of 218 (43%) students study social sciences, 192 (38%) technical sciences and 96 (19%) natural sciences. The survey was completed between 11 and 30 October 2021.

4. Results

4.1. Qualitative Research—Interviews: Reported Teachers’ and Students’ Challenges at Practicing Emergency Remote Teaching

All participants agreed that the sudden transition from face-to-face teaching to ERT caused changes in knowledge flow management and student engagement. Four types of challenges were identified by teachers and students: social, methodological, pedagogical, and technical (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Perceived challenges by teachers (N = 12) and students (N = 16) interviewed.

The first part of the discussion with teachers and students was focused on methodological and social challenges. Teachers were faced with the problem of adapting how they prepared and delivered courses. Before the pandemic lockdown, they felt comfortable teaching in physical classrooms, but ERT demanded changes for which they were not ready. Physical teaching institutions were temporarily closed, and suddenly, the only possible way of teaching was online. The transition to new approaches was inevitable and had to be implemented quickly. The speed of this change, which left teachers with little or no time to adapt to unique circumstances, was the biggest challenge for all the interviewed teachers, as they felt they were largely left to themselves, their knowledge and ingenuity. A professor from Spain (age ≥ 50 years, size of the student group: 35) indicated: ‘The big problem is the huge disparities in knowledge about what is called digital competence. Those who do not have digital competence may not have enough reaction time. Adaptability and reaction time is an issue. The first big challenge is to adapt without time.’

Educators who practiced a teacher-centered approach to teaching before the pandemic perceived more challenges than those who practiced a student-centered approach. Recall that according to a teacher-centered approach, the teacher determines the learning content, defines the teaching methods, and checks and evaluates how well the student has acquired the content [44]. According to the data collected from the interviews, the pandemic exposed and deepened problems that some teachers already had. Teachers began to understand the rationality of the transition to a student-centered approach, which focuses on what the student should be able to do on completion of the course. The teacher-centered focus on content alone was reflected in the challenging need to prepare extensive materials to replace face-to-face classroom interaction, (too much) homework (according to students’ opinions), and difficulties in digitizing assessments.

Since the transition to ERT, teachers reported that they have been intensively looking for new ways to deliver the learning content, focusing on quality. One of the professors involved in the study (Spain, age between 40 and 50 years, size of student group: 40) commented on this: ‘Difficulty applying active methodologies that we used to do in face-to-face’. Remote teaching was recognized as more challenging in terms of student motivation compared to face-to-face teaching. Interviewed teachers learned from experience that the prepared way of teaching and materials for remote learning should substantially differ from face-to-face ones since more diverse activities must be involved to motivate students instantly. Students associated the search for new communication channels and ways of presenting the learning material from teachers with a lack of teaching materials available at the beginning of ERT or course, making it difficult for them to follow the courses and achieve the learning outcomes set out. At the beginning of the pandemic, students did not appreciate the effort and intense work of teachers to adapt to ERT, and their endeavors were often considered a poorly done job.

Teachers who practiced remote teaching before the transition to ERT and those who taught theoretical knowledge reported that the transition to ERT was less demanding than those teaching practical skills. After one year of lockdown, many teachers of medicine, veterinary medicine, gastronomy, etc., had still not fully figured out how to effectively teach manual skills remotely in the absence of direct human contact. Students noted that teachers have difficulties performing practical and laboratory work requiring specific equipment. In this case, teachers often offered them simulation software tools instead of using the laboratory equipment at the location of HEI, or the practical content was presented only in theory.

The transition to online teaching was a more significant challenge for teachers trained in dynamic communication with students teaching in physical classrooms (i.e., face-to-face education). These teachers were very skilled at monitoring students’ engagement in the classroom and good at changing teaching methods according to the perceived level of engagement. However, they felt that they were unable to use these skills (i.e., students’ engagement monitoring) in a virtual learning environment. Additionally, the bigger the group of students, the bigger the challenge was. Over time, teachers took the approach to organize work in virtual breakout rooms and encouraged students to be actively involved in the work as much as possible, which increased the workload of the teacher as she/he had to monitor these breakout rooms.

The main characteristic of ERT was that most students did not turn on their cameras, sometimes claiming that they did not have them or that they did not work. Due to the often poor internet connection quality, teachers could not insist on the activation of student cameras. Some teachers admitted they never saw their students, even though they participated in the same online events. It is a fact that contact through online teaching tools was the only contact many students had at that time. Eye contact could not be established, and teachers could not receive information about the student’s body language, making it challenging to build student–teacher and student–student relationships. The comment from the professor from Spain (age between 30 and 40 years, size of student group: 25) about that was: ‘The other big challenge is the disconnection between the teacher and the student, the relationship is not the same. It causes the student to be more disconnected in certain circumstances. It depends on the age, with master’s students it doesn’t seem so common, they have more maturity.’ The disconnection intensified the feeling of loneliness and isolation for both teachers and students. Both groups were exposed to the possibility of addiction to virtual (unreal) life and physical and mental health issues, often in the form of anxiety and neuroses.

The fact that the cameras were turned off forced several teachers to conclude that they did not control what was happening in their online classroom. Teachers did not know whether the students understood the given content, how many of those who had joined the online class were actually following the class, what the students were doing behind the cameras, why there was no response to the questions asked, etc. Without control over what was happening and feedback, teachers had nothing to go on, and their motivation to improve ERT slowly decreased. Interviewed students often pointed out that asking the teacher a question in online sessions was more challenging than in brick-and-mortar classrooms. They had the feeling that the teacher could not see them. Many students gave up on the question. If they wanted an answer, they often had to interrupt the teacher somehow, which could exceed the limits of expected behavior. According to students, teachers needed more time during ERT to explain the same amount of teaching material than before in physical classrooms.

Another big challenge was conducting exams and assessments, especially for a group of teachers who practiced a teacher-centered approach. For the latter, even composing the questions was a problem. The novelty of ERT was that it was necessary to create secured, isolated environments in which it was possible to control the participants’ activities, access to the application, microphone, screen sharing, identity, etc. Even within these environments, however, teachers were not always sure that the delivered online assessments had been authored by the examinee.

The interviews were also aimed at identifying the technical challenges that teachers and students faced in the ERT transition. The obtained results are shown in Table 3. It can be seen that many of the interviewed teachers and students reported problems with their internet connection. The most common solution to poor internet connection was to turn off the cameras. Many activated microphones often caused problems with sound quality and, consequently, made communication difficult. A statement regarding this matter was provided by one of the participating professors from Slovenia (age ≥ 50 years, size of student group: 5–26): ‘Another problem is the slow response of students or direct communication with students. It is not possible to have cameras because there are problems with the internet. It’s hard to know if these students understand or not. If you want to communicate with students, it means you have to ask them by name, which means you have to have a attendance list, which you can’t see on MS Teams if you share a screen and only have one screen, then you don’t see the attendance list’. Solving technical issues often significantly reduced the time available for teaching. When the lockdown came into force, teachers and students were first faced with determining how much equipment they had available to conduct remote teaching and if it was functional and compatible with everything else in the emerging ERT environment. Mostly, the professors quickly bridged the missing equipment gap with the support of HEIs. When the HEIs acquired the necessary equipment, the teachers began to work on acquiring the skills to use the equipment. Interviewed teachers report a lack of technical staff to help everyone at once. Missing and inadequate equipment touched the students later, many not earlier than when they tried to join the online event. Some did not own cameras and microphones. Students were mainly able to follow the theoretical lectures. However, they had a more significant challenge with active participation in the tutorials, where the teacher shared a screen on which he or she demonstrated the use of the software. The students could only follow this productively if they managed two displays. They watched the teacher’s moves on the first display, and on the second, they performed the task themselves. A perspective on this was shared by one of the contributing professors from Slovenia (age between 40 and 50 years, size of student group ≥ 200): ‘I always work with some computer tools. It’s still good in lectures because I share a screen with them, and they see what I’m doing. The bigger challenge is in the tutorials, where they must have two screens—one to monitor what I do and one with a program in which they test themselves’.

Interviewed teachers also raised awareness of pedagogical challenges and lack of skills when implementing ERT (professor from Spain, age between 30 and 40 years, size of student group: 25): ‘We need more training; how does a student learn?’. Several interviewed teachers scored their pedagogical skills as low since their main focus was mainly on the field of research-specific skills. HEIs do not usually require teachers to have a high level of pedagogical competence but rather seek academic excellence. The transition to ERT did not create but only revealed and deepened the problem of low pedagogical competence of teachers. The interviewed teachers most often reported the following challenges: not knowing effective ways of teaching new generations of students; not knowing how students learn, and not knowing how to motivate students. For instance, many were untrained in using e-learning platforms, video conferencing software, and other platforms and programs beneficial for ERT. In Table 3, readers can see that one particular pedagogical method—the creation of 3–5 min videos—is emphasized among several general challenges. This emphasis is due to the proven ability of educational videos to stimulate multiple senses simultaneously, providing a diversified means of transmitting information. Such an approach enhances the learning process, making it more effective and engaging, especially in technical education, where complex and challenging problems often need to be addressed [45]. Using videos also stimulates the student’s reflection and improves their teaching skills [46]. Therefore, this knowledge is significant for educators, especially when the majority of the educational process is taking place online. More pedagogical challenges identified from the interviews are reported in Table 3. After a few months of lockdown, the majority of HEIs started offering employee training, but it seemed that it was too late as the courses were already running.

For teachers conducting hybrid online events, it was very challenging to maintain a balanced focus on students in the physical classroom and those who were connected online. It was almost impossible for them to motivate and support communication in two parallel teaching channels. Interviewed students who participated in the sessions remotely, often felt forgotten by the professor. When they tried to ask a question or participate in a debate developing in the physical classroom, they could not hear the voices of all the participants. The interviewed teachers recognized hybrid teaching as the most demanding for them to implement, while the students described the hybrid method as one with which they least want to be taught.

After the lockdown, some students raised concerns about the sudden halt in study activities and the subsequent expectation for them to rely solely on independent work. Teachers and students also pointed out that most of their challenges were the consequence of the rapid transition to ERT. The ERT was rapidly established, but some challenges still persist(ed). Students also reported technical challenges with microphones, cameras and poor internet connections. Interviewed students perceived the teachers’ low digital literacy, especially among the older staff. In relation to this, a student from Slovenia (age ≥ 20 years, master’s program) articulated their observation as follows: ‘The disadvantage is also the qualification of some professors—especially among the elderly, the quality is very familiar because they are not skilled in working with information technology. As a result, time that would otherwise be devoted to effective lectures (from 45 min to an hour then only 30 min) passes for the purposes of preparing computers, presentations’. They pointed out that this was a common reason they needed more time to deal with teaching content than expected in a physical classroom. Students were often bored by the teachers’ clumsy use of software tools. Regarding this issue, a student from Slovenia (age ≥20 years, master’s program) conveyed their observation in the following way: ‘In the beginning, we didn’t have the right tools, and the lecturers didn’t know how to prepare a lecture’. From the students’ point of view, the most challenging aspect of ERT was to maintain concentration during the online sessions and motivation levels. Their attention span was shortened due to a lack of participation and interaction. Teachers conducted online activities monotonously, without dynamically changing approaches, and teaching content was communicated only verbally without drawing and writing on the whiteboard. Students felt like they were watching a video most of the time. In doing so, they were in the comfort of their homes, exposed to far more distractions than in the HEI environment (student from Spain, age ≥ 20 years, university degree): ‘With Virtual class, it is hard to maintain focus and my attention span is shortened due to lack of participation and interaction’. Their identified challenges were manifested in the form of an excessive workload and low self-discipline. In addition, it was noted by students that they understood less of the content delivered than before the onset of ERT.

4.2. Quantitative Research—Survey: A Detailed Insight into the Perceived Difficulty of Challenges in Implementing Emergency Remote Teaching

After interviewing teachers and students (see Qualitative research in Figure 1), two questionnaires, one for teachers and one for students, were prepared to assess the perceived difficulty of the challenges raised by surveying a large number of teachers and students at an international level. The survey results are reported separately for students and teachers.

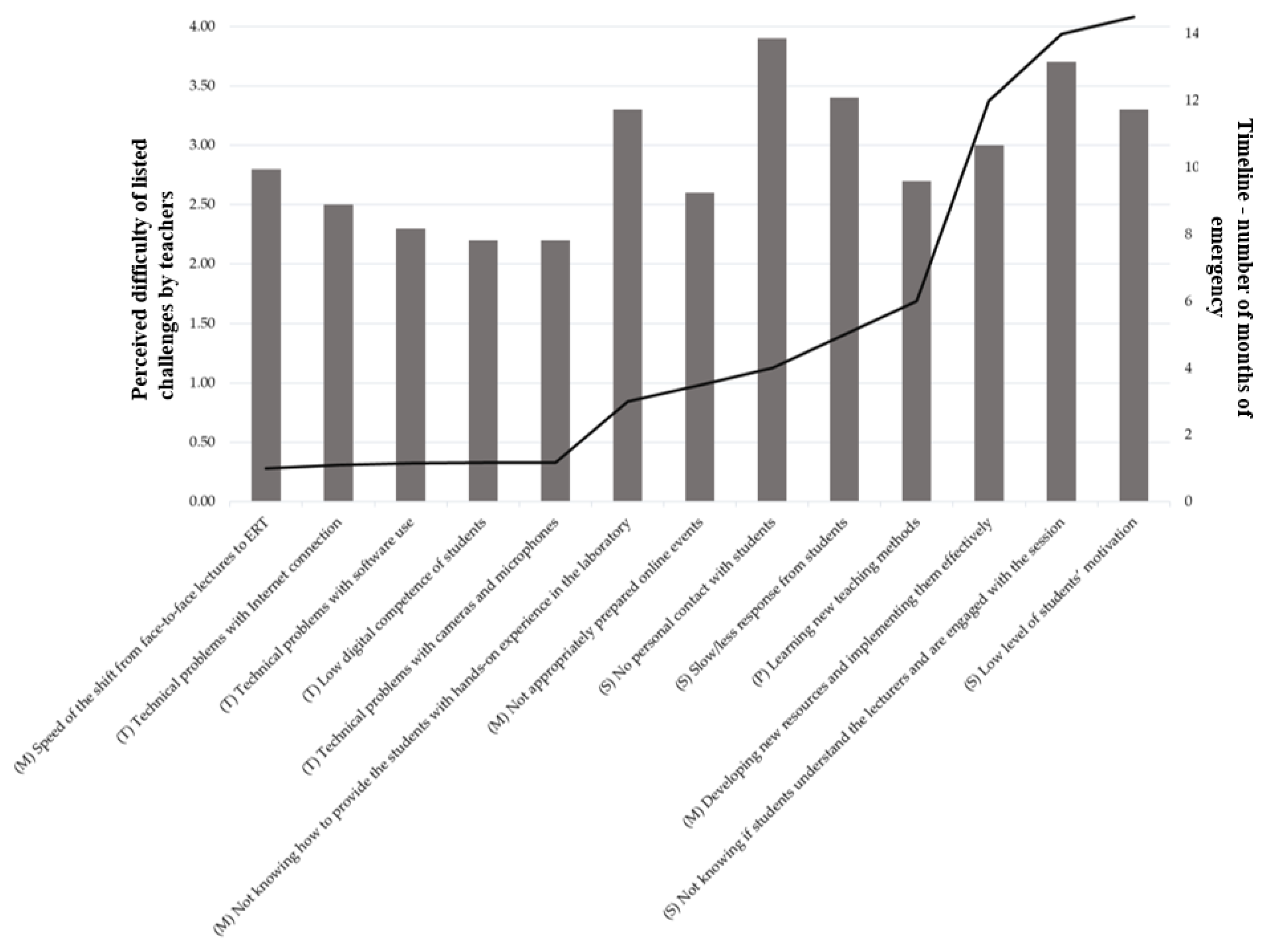

4.2.1. An Insight into the Perceived Difficulty of Challenges from the Teachers’ Perspective

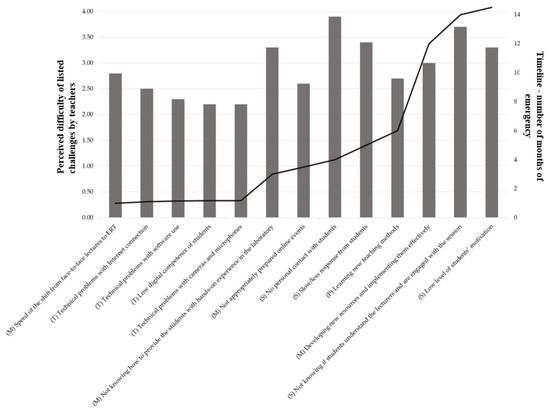

Table 4 lists the teachers’ challenges identified in implementing ERT, ranked from very challenging (4) to least challenging (0). It is worth mentioning that ERT can be implemented in a 100% online format or using a hybrid learning approach. On average, teachers performing online class activities rated social interaction (3.6) as more challenging than technical interventions (2.3). Adapting to new methodologies was also considered challenging on average (2.9) but less than social interaction (3.6) and more than pedagogical (2.7). The same pattern can also be seen in the responses of teachers who practiced hybrid activities. On average, teachers performing hybrid activities rated social challenges (3.28) as more outstanding than methodological challenges (2.8), pedagogical (2.6) and technical ones (2.25), respectively. The development of new resources and overcoming technical problems were also identified as considerable challenges. However, the difficulty ratings for technical issues such as internet connectivity, software and hardware are relatively low, which may indicate that these are seen as easier to overcome compared to educational and social challenges.

Table 4.

Perceived difficulty of listed challenges by teachers (N = 276).

Previous scientific studies (see Section 2) have already mentioned the social challenges, namely students’ engagement and motivation. The present study adds the challenge of not knowing if students understand the lecturers. Respondents rated this challenge on average with 3.7. Among the top three challenges named by the teaching community, the lack of personal contact between professors and students (3.9) and the less and slower responses from students (3.4) stood out. The challenges associated with personal interaction are, therefore, found to be most difficult in online and hybrid modes, suggesting that the lack of personal interaction is a significant challenge for teachers and should be supported in the implementation of ERT.

Low student motivation was found to be a common challenge in both modes (i.e., online and hybrid), although it was found to be slightly more challenging in the online environment. This may suggest that hybrid models can offer some improvement in student engagement compared to online-only modes. In the hybrid mode, teachers found it challenging to implement collaboration between students (3.1) who were present, some in physical and some in virtual mode (i.e., hybrid). If, in some cases, the teacher could see all the students, physically and virtually present, the students of the two groups most certainly could not see each other.

Teachers found it challenging to develop a way to transfer the experience that students would gain in a laboratory environment to online mode (3.3). Recall that laboratory work includes using devices not usually available in the home environment, senses, emotions, etc. The perceived level of difficulty of this challenge was slightly higher for online teaching (3.3) compared to hybrid (3) approaches.

The survey did not confirm that teachers who had been teaching for a more extended period of time considered the challenges listed in Table 4 as less demanding compared to their less experienced colleagues or vice versa.

The difference in opinions about the perceived difficulty of the challenges between countries was statistically significant for the following challenges (independent samples Kruskal–Wallis test):

- Quick changes from live classes to online classes (p = 0.007);

- Learning new teaching methods (p < 0.001);

- Developing new resources and implementing them effectively (p = 0.009);

- Not appropriately preparing lectures (p = 0.045);

- Slow/less response of students (p = 0.001).

As the majority of respondents in the sample originate from Poland, Slovenia, Spain and Italy, the cultural differences between these countries could explain these differences. There is a clear difference in how the participants from Poland and Italy perceive the challenges of rapid change. Specifically, 53.19% of participants from Poland do not find the rapid changes challenging, while most participants from Italy (52.94%) see them as challenging. In particular, the aspect of ‘learning new teaching methods’ is perceived as less challenging by 50% of Polish participants, while in Slovenia, 43% perceive this as very challenging. In addition, participants from Slovenia express challenges in various areas, including ‘Developing new resources and implementing them’ (52.27%), ‘Lectures not adequately prepared’ (36.36%) and ‘Slow/low student response’ (79.55%). In contrast, participants from other European countries (except Poland, Italy and Spain) do not see the development of new resources as challenging (46.15%), 73.08% do not see inadequately prepared lectures as challenging and 38.46% find that less response is a challenge. Notwithstanding, their perspectives about the difficulty of the other challenges listed in Table 4 are not statistically significantly different.

Teachers need 6 to 9 months to be ready to deliver fully online university courses in non-crisis conditions [7]. Therefore, the lack of time can be a problem when switching to ERT. This was also noted by the surveyed teachers, who, on average, assessed the ‘Speed of the shift from face-to-face lectures to ERT’ as challenging (2.8 in Table 4). In the survey, teachers were asked how much time they spent preparing one pedagogical hour performed physically face-to-face, online and hybrid. As can be seen from Table 5, teachers spent more time preparing online and hybrid pedagogical hours than preparing face-to-face ones. Most teachers (36.6%) spent 1 to 2 h preparing one pedagogical hour performed in a physical environment (i.e., face-to-face), while this time is extended to 2 to 4 h for online (38.3% of teachers) and hybrid (28% of teachers) preparation. If it takes more than 4 h for 10% of the surveyed teachers to prepare a one-hour in-person class, then over 23% of those who teach online faced the same lengthy preparation time for their classes in ERT.

Table 5.

Average time to prepare one pedagogical hour for different teaching modes of ERT.

There are no statistically significant connections between teachers’ opinions regarding the duration of preparation of one pedagogical hour of lectures/tutorials and the student group size. A statistically significant difference in opinion about the time spent for preparation of 1 pedagogical hour is present between Spain and Slovenia (p = 0.011), Spain and Poland (p = 0.000) and Italy and Poland (p = 0.001).

Considering teachers’ reports that preparing one pedagogical hour in ERT is more time-consuming than preparing face-to-face in non-crisis time, we would assume that they spent additional time preparing teaching materials for students during ERT. In Table 6, it can be seen that the majority of surveyed teachers reported that the same amount of teaching material was processed (i.e., delivered) in one pedagogical hour. Those who claimed they processed less teaching material per one pedagogical hour in online or hybrid mode than face-to-face were asked to reveal the circumstances of such reduction. Eight teachers (47% of all) who processed less material had trouble presenting it effectively, so they repeated it. Five teachers (29% of all) spent more time answering questions because students were asking more than they did regularly. In the case of hybrid teaching, seven teachers (39% of all) who processed less material had trouble presenting it interestingly, so they repeated it. Three teachers (17% of all) did not feel confident with ICT, and as a result, they processed less material at the expense of time-consuming ICT issues.

Table 6.

Comparison of the average amount of prepared teaching material for students by teaching mode.

A small proportion of teachers reported an increase in the average amount of processed teaching material when preparing online (13%) and hybrid (3%) teaching compared to teaching in a face-to-face classroom. Those who claimed that they processed more teaching material were asked to reveal the circumstances of such an increase. Two teachers reported processing more teaching material because students did not respond to their debate initiatives. Another two considered that they gained additional time due to less work with students and preparation for the teaching process in the virtual classroom. In the case of hybrid teaching, three teachers (17% of all) managed to process more teaching material because students did not respond to their debate initiatives and spent less time on questions.

Statistically, there are no significant differences in opinions on the average amount of knowledge processed per teaching hour, whether among teachers with different-sized student groups or between countries.

4.2.2. An Insight into the Perceived Difficulty of Challenges from the Students’ Perspective

Table 7 presents the perceived difficulty of the listed challenges faced with online and hybrid teaching by students. According to these reports, students found social challenges to be more daunting than technical ones. The most challenging aspect for the students was that they did not have opportunities for spontaneous student–student contact (3.6). The students were aware of their unwillingness to speak out but did not try to improve it, as they could not respond to the teachers’ efforts to initiate a discussion. They observed the challenges with a lack of self-discipline (3.3). The students rated quite critically teachers’ digital literacy (3.1). Collected data shows that students found the lack of face-to-face contact with teachers and peers and the predominance of voice-only communication a major challenge, indicating a preference for more interactive and visually supported methods of communication. Students felt that the rapid transition to online learning negatively impacted the quality of online lectures and tutorials. This could be due to problems in adapting course material for online delivery and the need for better preparation for emergency teaching scenarios.

Table 7.

Perceived difficulty of listed challenges by students.

As shown in Table 7, students perceived fewer challenges in the hybrid mode (15) compared to online classes (5). Self-discipline is recognized in online mode as the most challenging aspect (3.1), followed by technical problems with the internet connection (3.0) and the fact that the teachers, in their opinion, were not able to maintain the attention of all the students (3.0).

Due to the recognized low level of motivation among students participating in ERT, we inquired about the specific factors that motivated the students. A list of six potential motivational factors were offered to the students and they were asked to assess how likely motivational factors affected their engagement on a scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely). Potential motivational factors were selected based on interviews and the literature review results. The survey revealed (see Table 8) that the teacher’s teaching methods (4.4) significantly impacted their engagement. An equally powerful motivator is personal interest in the course content (4.4). The third strong motivation factor is the strength of desire to complete studies (4.1). The survey revealed that among the six highly influential motivational factors, the teacher can influence students’ engagement only through two, namely teaching methods and access to materials.

Table 8.

The perceived impact of motivational factors on students’ engagement during ERT.

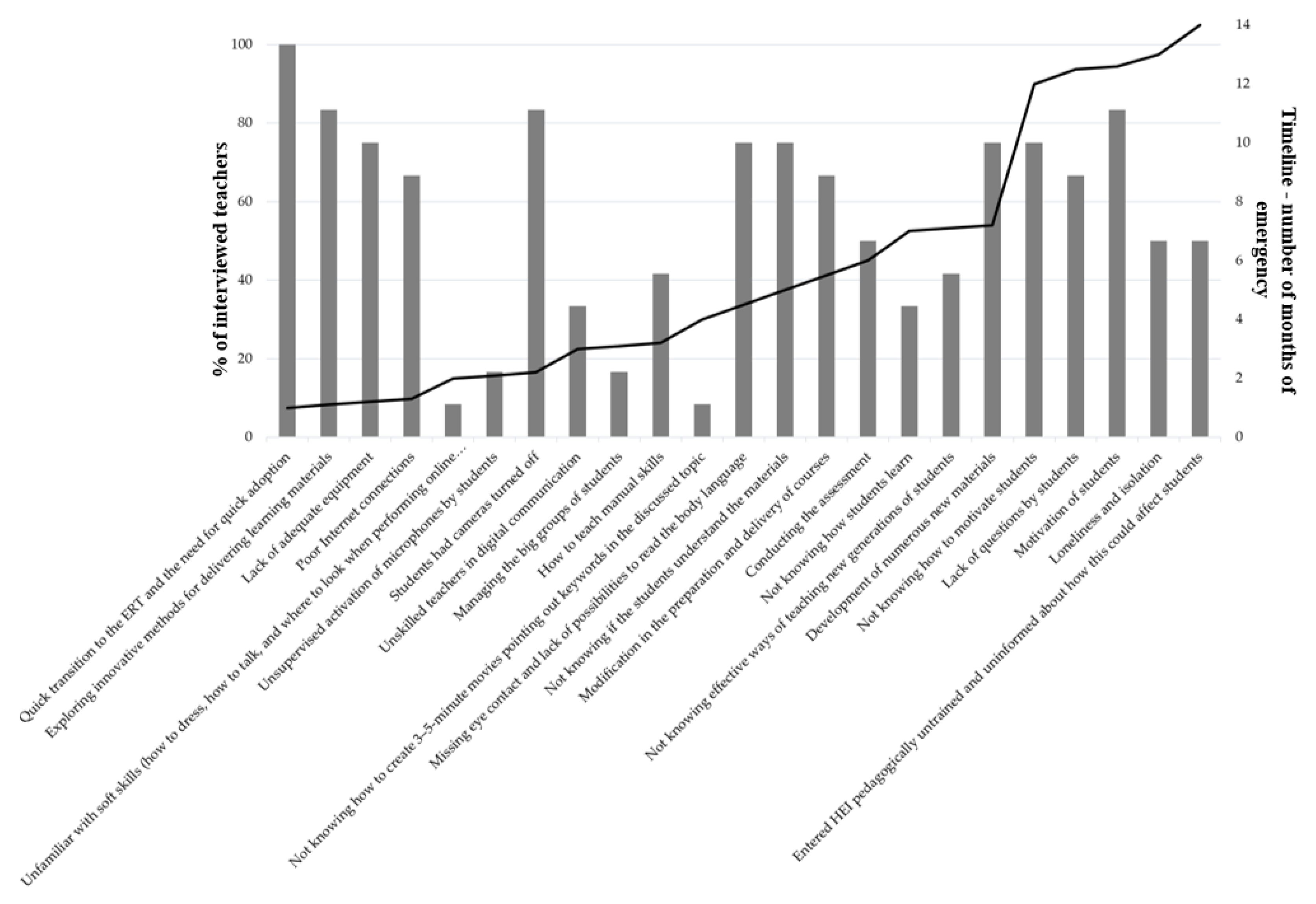

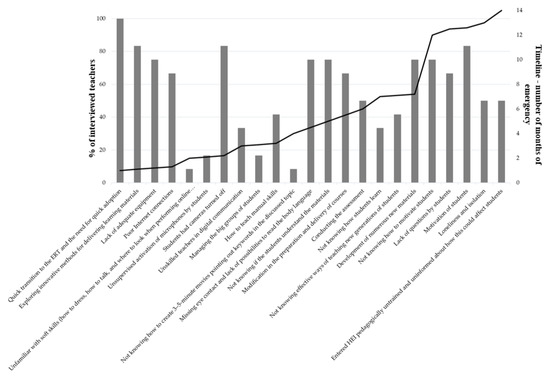

The chronology of the ERT introduction explains the perceived difficulty level of different types of challenges. In fact, potential new deployments of ERT will probably not be very different from the lockdown experience due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The lack of electrical and gigabyte infrastructure, essential hardware and software characterized the beginning of ERT. Figure 2 and Figure 3 represent graphs that show the times teachers most frequently discussed specific challenges. A line graph (scale on the right side of the chart) can be used to follow the chronology, and a bar graph (scale on the left) can be used to follow how many teachers and students from our study highlighted each challenge. As can be seen from Figure 2 and Figure 3, the beginning of ERT (the first 3 months) was characterized not only by various technical challenges (the predominant challenges of this period, as reported by the participants, are lack of adequate equipment; poor internet connections; technical problems with cameras and microphones; and technical problems with software use), but also by problems related to confusion about the rapid transition to ERT and the exploration of new teaching methods (quick transition to the ERT and the need for quick adoption; exploring innovative methods for delivering learning materials; not knowing how to provide the students with hands-on experience; and not appropriately preparing online events). When the equipment was in place, teachers and students needed skills to use it (the challenges addressing this area and brought to attention are being unfamiliar with soft skills and being unskilled in digital communications). At the time of conducting research interviews, this phase of ERT had already passed, and technical challenges were no longer at the forefront of teachers’ and students’ perceptions. The introduction of ERT continued with solving pedagogical and methodological challenges, which contributed to the planning of ways to deliver learning content and maintaining communication between participants in the pedagogical process. The teachers faced challenges, particularly in the 6–8 months following the onset of ERT (the important challenges of this period are the development of new materials, learning new teaching methods, not knowing how to motivate students, lack of questions by students, and slow/less response from students). However, when teachers finally started teaching online or hybrid, social interaction came to the fore in the last period of the timeline (8 month and onwards) as loneliness and isolation as well as not knowing if students understand the lecturers because of no personal contact and low motivation of students.

Figure 2.

Perceived challenges by teachers (N = 12) presented on a timeline.

Figure 3.

Perceived difficulty of listed challenges by teachers (N = 276) presented on timeline.

5. Discussion

The results of the present study clearly show that various types of challenges had different effects on teachers (Table 4) and students (Table 7) depending on the time of observation in the ERT life cycle. It can be seen that both teachers and students emphasize the impact of limited personal contact and underline the central role of interpersonal relationships in the educational process during ERT. Teachers and students are equally concerned about technical issues, including internet connectivity and equipment problems, although these are not rated as the most pressing challenges. The challenges associated with moving to online teaching and learning, such as developing new resources and adapting to rapid change, are acknowledged by both sides. Teachers express more concern about the slow/lack of student response, indicating a possible expectation gap between immediate teacher feedback and student engagement. Students cite challenges related to self-discipline and motivation, aspects not directly acknowledged by teachers, indicating a student-centered awareness for mastering independent learning.

Although the initial literature review was used as a basis to conduct interview protocols and questionnaires for surveys, the interesting differences concerning some of the problems described in the study can be noticed. Obtained results in this work confirm some of the findings in previous research. However, new causal relationships have been found in several cases. For instance, technical challenges related to a lack of devices [6,17,19,21,25] and difficulty in accessing online tools [26] have been firmly identified in the literature review. Nonetheless, these challenges did not appear as prominent in interviews and survey responses. This could be motivated by the fact that these challenges were addressed in the first phase of the ERT, as has already been pointed out. A lack of digital skills among students and teachers [4,6,17,28,29] has also been identified in the literature review. In this work, it has been shown that teachers also emphasized the lack of digital communication and soft skills during the interviews. Interestingly, despite students’ perception of this gap, teachers did not mention the lack of digital skills in the survey. The literature has shown a need to develop new materials and teaching methods [6,17,25,30,31,32,33,34] to address the lack of systematic material. Interviews and surveys have revealed that professors are having difficulty with fundamental aspects, such as teaching manual skills online, understanding students’ learning processes, or presenting information engagingly and effectively to the next generation of students. In the online environment, they also have difficulty in conducting effective meetings. The transition to ERT has revealed a lack of motivation among students and an absence of interactivity during lectures [6,16,17,24,25,26,35,36,37], which was confirmed by our research. In addition, it was found that teachers linked the lack of student interaction and motivation to students not asking questions. On the other hand, we have seen that students felt constrained to ask questions because they feared they might disturb a teacher, and some did not want to stand out by using microphones. According to the conducted surveys data, it has been found that low student motivation was linked to uninteresting lectures and tutorials, leading to decreased personal motivation to study and reduced personal discipline. In addition, interviews have revealed that the lack of interactivity in lectures is more pronounced for larger groups of students where it is difficult to include everyone in an online discussion. Also, we have identified the challenge of not using cameras at meetings [16] and, thus, a lack of eye contact between teachers and students. This lack of response by students, coupled with the difficulty for teachers to assess how well they could understand the material, has also hampered their interpretation of visual and body language. Professors in both the interviews and surveys considered this task to be a problem, and this is an issue that has not been identified in the conducted literature review.

Considering that the potential that future crises will require the re-implementation of ERT is high [47] and considering the findings of this research, we propose a set of guidelines below to strengthen higher educational systems in non-crisis times, bolstering their resilience, sustainability, and ability to implement and withstand ERT effectively. To frame these guidelines within the work of previous authors, they have been divided into four categories: technical (T), methodological (M), pedagogical (P), and social (S).

- Intensive establishment of gigabit infrastructure and equipping households—as well as educational institutions—with essential information and communication equipment for virtual communication. According to interviews with professors and students, when ERT started, technical challenges, such as internet access, were the most present and, to a lesser extent, represented an insurmountable obstacle. Many students did not own cameras. However, when the cameras were bought, it turned out that many switched-on cameras slowed down or even interrupted the online event. The switched-on cameras have often disturbed the participants’ focus, as they had an insight into the intimacy of the home environment of others. It slowly became a given that the cameras remained off. Teachers who used ICT for all teaching hours for the first time during the imposed transition to ERT turned out to be poorly prepared and unprofessional in the eyes of the students. The resulting slow processing of teaching material often bored students and allowed them to shift their attention to other stimuli from their home environment.

- Familiarize students and teachers with the nature of virtual environments. During the initial implementation of ERT, teachers had to learn how to teach in front of cameras, setting a neutral background, dressing, etc. Students did not receive these skills. Even though the teachers improved their approach to teaching in front of cameras, it did not stop the students from retreating behind the cameras. It was detected that there was also a discernible reduction in the level of interaction between teachers and students. The teachers rated the difficulty of this challenge highly, as they did not know how their specific teaching method in front of the cameras affected the students’ engagement. Some of the interviewed teachers have stopped improving themselves pedagogically precisely because of the lack of feedback. Teachers’ and students’ digital competencies need to be developed synchronously since ERT requires competence on both sides. Including some virtual sessions in the regular lectures could contribute to addressing this situation. Indeed, it can be argued that HEIs that permanently teach online are more resilient to crises than those that traditionally teach students in physical classrooms. With them, technical challenges in the transition to ERT are hardly to be expected. Also, a minimal occurrence of methodological and pedagogical challenges could be expected due to a busy schedule with interventions of support services within HEIs.

- Continuous upgrading of digital competencies and training materials. Interviews with professors revealed a challenge of low teachers’ digital, methodological, social, and pedagogical competencies during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was solved by the individual’s self-education or education initiated by the HEIs. This complicated the task of adapting the existing training materials to new learning environments. It could be argued that post-lockdown teachers are better qualified to implement online teaching than pre-ERT on average. In the interviews with the professors, we also noticed that only 10% of them upgraded their competences beyond the necessary scope. We could conclude that after the end of ERT, most professors stop upgrading their competences (and training materials) if there is no external motivator. The present study concludes that the core challenge is not a lack of students’ motivation or engagement but rather a mechanism that would motivate teachers and students to improve.

- Foster the usage of multiple communication channels between participants in the pedagogical process. After a year and a half of the imposed transition to ERT, the social challenges completely overshadowed the technical ones. Social challenges, also researched by [6,16,17,24,25,26], were observed to the greatest extent in online teaching and less in hybrid and distant modes. Despite meeting in real-time in the online classroom, there was a lack of communication, which could have smoothed the stress of teachers and students. Students inherently predisposed towards shyness and reservedness faced limited opportunities to transcend their natural limitations, as the teachers could not detect their condition due to the cameras being switched off. The lack of communication made it difficult for all students to participate, which is one of the characteristics of sustainable learning. Sustainable learning is defined as long-lasting, continuous, participative, purposeful, renewable, and habitual [38,48].

- Co-creation of educational systems with HEIs, teachers, and students. Past experiences with ERT have revealed that teachers face the challenges of ERT organized within the auspices of the departments, while the students are not organized to function as a unit in times of crises. The teachers were able to foresee the challenges because, despite the lockdown, there was minimal time for planning. HEIs, on the other hand, put students in front of the facts with almost no choices. Involving students in the planning phase of ERT would help reduce stress on the part of students and allow them to prepare themselves and solve potential problems earlier. Teachers would be aware of students’ challenges, and students would be aware of teachers’ challenges. They would mutually develop a platform of trust and a sense of safety, which is the basis for information exchange and interaction. The lack of interaction was mainly reflected in the students’ lack of motivation, shortened students’ attention span, and unresponsiveness. Investing efforts in organizing students into operational units during non-crisis times can pay off during ERT in the form of greater student engagement and, consequently, better learning outcomes.

- Stimulate students’ motivation and engagement by exploring different teaching methods and tools. Researching live examples of ERT revealed that low student motivation stood out in the field of social challenges. It is believed that if teachers can help students develop a strong motivation to learn, this can significantly improve students’ learning outcomes [49]. Experiments in educational psychology show that students’ motivation drives learning activities, stimulates students’ interest in learning, maintains a certain level of arousal, and leads to certain learning activities [50]. Teachers should constantly try new teaching methods and plan interesting activities to stimulate students’ interest in learning and thus enhance their subjective initiative [49]. To motivate students, it is necessary to know what motivates them, but contrary to expectations, interviewed teachers in the present research reported a lack of knowledge on how their activities in front of cameras encourage students. The current study also confirms a lower level of pedagogical competences of teachers as already discussed by other authors [6,21,23,24,27,30]. During ERT implementation, teachers recognized the need to adapt teaching methods to the ERT teaching environment. However, they were less aware of where to get acquainted with appropriate teaching methods and how different teaching methods could be effectively used within ERT. As a result, teachers mostly refrained from choosing the most suitable teaching methods, clinging to previous knowledge as they tried to cope with the preparation of teaching materials, monitoring the student performance, and finding ways of formative assessment that were compatible with ERT. The teachers interviewed admitted that they knew that many online applications and software tools were available to help them with ERT, but they lacked time and energy to find them and learn how to use them. The challenge of learning how to use different online teaching aids was already discussed in the scientific literature before the imposed transition to ERT [51,52]. The lockdown only made the challenge relevant in practice. The present study supports the need for the creation of databases of teaching methods and digital teaching aids, as well as the result of illustrative short instructions that help future users to master the necessary basics in a very short time.

To sum up, the digital, methodological, and pedagogical competences of higher education teachers should be continuously improved, even in non-crisis times. Special attention should also be paid to the systematic improvement of students’ digital competences and the encouragement of their organized activities in the digital environment. Many HEIs ignore the latter. The biggest weakness of the last ERT was the lack of involvement or the late involvement of students in the planning of ERT solutions. The current post-ERT phase should be taken advantage of to develop tools to help teachers find, test, and use hardware, software and teaching methods more quickly. Collecting good practices and making them visible to wider communities is essential. Finally, it is worth noting that social challenges are present in online and hybrid teaching modes, regardless of whether it is ERT or teaching in non-crisis times, they cannot be neglected.

6. Conclusions

Nowadays, the restriction of socializing is over, and HEIs have mostly switched back to traditional face-to-face teaching in physical classrooms. However, as a consequence of the pandemic and ERT, teachers have returned to the teaching environment with improved digital literacy and at least a basic knowledge of many new methodological and pedagogical approaches. HEIs should take advantage of this situation and consider developing educational systems based on more information and communication channels. Students should also be more intensively involved in the planning process and constantly upgrading competences.

The imposed transition to ERT happened globally—and it can happen again [48]. HEIs, teachers and students were faced with an unprecedented challenge. The challenge was multidimensional, comprising technical, pedagogical, and social dimensions. This research has identified the most demanding teachers’ and students’ challenges when exposing them to ERT, classified these challenges according to the perceived level of difficulty, and proposed guidelines for the design of resilient education. The most important conclusion is that the technical challenges during the development of the pandemic were resolved reasonably quickly, while pedagogical and social challenges were and are still latent both during ERT and non-crisis times. This finding might support and stimulate the development of tools (e.g., [53]) aimed to help eliminate persistent problems faster.

However, some challenges remain and are still relevant in post-ERT time. To quote one of the interviewed teachers: “Teachers need support”,… “I want to do this, and I don’t know how…”. Teachers need help in real time. In times of crisis, the technical staff are only available to bridge emergencies. From this comes the opportunity for further research and development.

The importance of the research presented in this article lies precisely in conducting research during health crises, which provides a valuable opportunity for such research. Even if there were a desire to improve certain aspects of the challenge in non-crisis times, conducting this type of research would be impractical. Many aspects of the challenge have been relegated to the background and forgotten, highlighting this research’s unique temporal and contextual value.

A limitation of this study is that participants were not surveyed about the resources available at their respective higher education institutions and were not asked to report the proportion of their educational assignments completed in online or hybrid formats before implementing emergency distance learning. Both aspects are crucial in understanding how educators successfully navigated the transition to Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) at the outset. On the other side, all the findings may be representative of only some of the population, not all parts of the world. Even though teachers and students from 27 different countries have been included in the sample for the survey, most participants belong to Europe. It is important to note that the development of HEIs and the availability of teaching and learning equipment may vary from country to country, especially in developing countries where we have not had a participant. The authors recognize that the results of these interviews depend on participants’ memories, which may be interpreted differently according to their own experience. In addition, the authors acknowledge that their findings can be influenced by the subjective nature of the participants or by their own biases in the formulation of questions and interpretation of responses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Š. and B.G.; methodology, S.Š., J.N., X.S.-B. and B.G.; formal analysis, S.Š., J.N., X.S.-B., A.Z. and B.G.; investigation, S.Š. and B.G.; resources, S.Š., J.N., X.S.-B. and B.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Š. and B.G.; writing—review and editing, X.S.-B., A.Z. and J.N.; visualization, S.Š.; supervision, B.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by Programme Erasmus+, Knowledge Alliances, Application No 2020-1-PL01-KA226-HE-096456, HOTSUP: Holistic online Teaching SUPport.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of La Salle Campus Barcelona (protocol code 2020102901_ERASMUS+_HOTSUP_v2020102301_public approved in 27 October 2020).

Data Availability Statement

Data is available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0). The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [OSF] at http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/H67EZ (accessed on 23 January 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Crawford, J.; Butler-Henderson, K.; Rudolph, J.; Malkawi, B.; Glowatz, M.; Burton, R.; Magni, P.A.; Lam, S. COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2020, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S.J. Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects 2020, 49, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, D.T.; Shannon, D.M.; Love, S.M. How teachers experienced the COVID-19 transition to remote instruction. Phi Delta Kappan 2020, 102, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trust, T.; Whalen, J. Should teachers be trained in emergency remote teaching? Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2020, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Pillay, A. South African Postgraduate STEM Students’ Use of Mobile Digital Technologies to Facilitate Participation and Digital Equity during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P.; Guzzo, T. Online Learning and Emergency Remote Teaching: Opportunities and Challenges in Emergency Situations. Societies 2020, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educ. Rev. 2020, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Khlaif, Z.N.; Salha, S.; Kouraichi, B. Emergency remote learning during COVID-19 crisis: Students’ engagement. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 7033–7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achen, K.; Rutledge, D. The Transition from Emergency Remote Teaching to Quality Online Course Design: Instructor Perspectives of Surprise, Awakening, Closing Loops, and Changing Engagement. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2023, 47, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquero, V.V.; Arce, N.G.; León, S.M. Transitioning from face-to-face classes to emergency remote learning. Rev. Leng. Mod. 2022, 10, 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Chung, S.Y.; Ko, J. Rethinking teacher education policy in ICT: Lessons from emergency remote teaching (ERT) during the COVID-19 pandemic period in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Sharma, R.C. Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to CoronaVirus pandemic. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2020, 15, i–vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Pradas, S.; Hernández-García, Á.; Chaparro-Peláez, J.; Prieto, J.L. Emergency remote teaching and students’ academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlejohn, A.; Gourlay, L.; Kennedy, E.; Logan, K.; Neumann, T.; Oliver, M.; Potter, J.; Rode, J.A. Moving Teaching Online: Cultural Barriers Experienced by University Teachers during COVID-19. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2021, 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.; Jung, H. Exploring University Instructors’ Challenges in Online Teaching and Design Opportunities during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2021, 20, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arja, S.B.; Fatteh, S.; Nandennagari, S.; Pemma, S.S.K.; Ponnusamy, K.; Arja, S.B. Is Emergency Remote (Online) Teaching in the First Two Years of Medical School During the COVID-19 Pandemic Serving the Purpose? Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2022, 13, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramarenco, R.E.; Burcă-Voicu, M.I.; Dabija, D.-C. Student Perceptions of Online Education and Digital Technologies during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Electronics 2023, 12, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drane, C.; Vernon, L.; O’Shea, S. The Impact of ‘Learning at Home’ on the Educational Outcomes of Vulnerable Children in Australia during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Literature Review prepared by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education; Curtin University: Bentley, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Wan, B. The digital divide in online learning in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owusu-Fordjour, C.; Koomson, C.K.; Hanson, D. The impact of COVID-19 on learning—The perspective of the ghanaian student. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2020, 7, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J.E.; Pohan, C. Resilient Instructional Strategies: Helping Students Cope and Thrive in Crisis. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2021, 22, ev22i1.2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ülger, K. Uzaktan Eğitim Modelinde Karşılaşılan Sorunlar-Fırsatlar ve Çözüm Önerileri. Intern. J. Contemp. Educ. Stud. 2021, 7, 393–412. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachopoulos, D. COVID-19: Threat or Opportunity for Online Education? High. Learn. Res. Commun. 2011, 10, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizka, L.; Probst, G. Learning during (or despite) COVID-19: Business students’ perceptions of online learning. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2023, 31, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir-Inbal, T.; Blau, I. Facilitating Emergency Remote K-12 Teaching in Computing-Enhanced Virtual Learning Environments during COVID-19 Pandemic—Blessing or Curse? J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2021, 59, 1243–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.M.M.A.; Alhamad, M.M. Emergency remote teaching of foreign languages at Saudi universities: Teachers’ reported challenges, coping strategies and training needs. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 8919–8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, B.N.Y.; Ahmad, J. Are we Prepared Enough? A Case Study of Challenges in Online Learning in A Private Higher Learning Institution during the COVID-19 Outbreaks. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 7, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, B.; Trippenzee, M.; Fokkens-Bruinsma, M.; Sanderman, R.; Schroevers, M.J. Providing emergency remote teaching: What are teachers’ needs and what could have helped them to deal with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 118, 103815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimers, F.; Schleicher, A.; Saavedra, J.; Tuominen, S. Supporting the Continuation of Teaching and Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Annotated Resources for Online Learning. Available online: https://globaled.gse.harvard.edu/files/geii/files/supporting_the_continuation_of_teaching.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Bacon, K.L.; Peacock, J. Sudden challenges in teaching ecology and aligned disciplines during a global pandemic: Reflections on the rapid move online and perspectives on moving forward. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 3551–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, K.; Javed, K.; Arooj, M.; Sethi, A. Advantages, Limitations and Recommendations for online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era: Online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, S27–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, D.C.; Grajek, S. Faculty Readiness to Begin Fully Remote Teaching. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2020/3/faculty-readiness-to-begin-fully-remote-teaching (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Johnson, N.; Veletsianos, G.; Seaman, J. U.S. Faculty and Administrators’ Experiences and Approaches in the Early Weeks of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Online Learn. 2020, 24, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Gregersen, T.; Mercer, S. Language teachers’ coping strategies during the COVID-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System 2020, 94, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]