Geocultural Heritage as a Basis for Themed GeoTown—The “Józefów StoneTown” Model in the Roztocze Region (SE Poland)

Abstract

1. Introduction

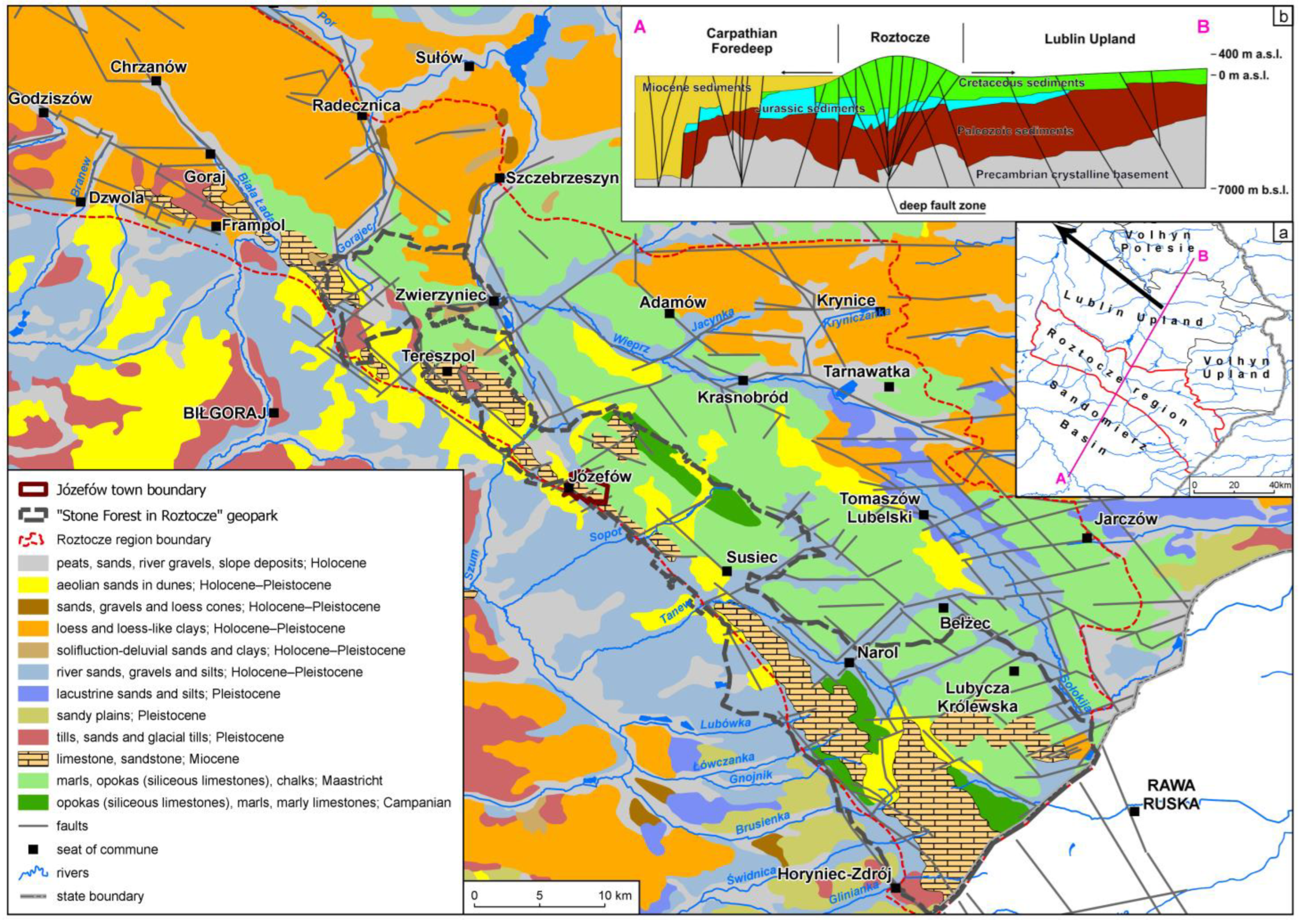

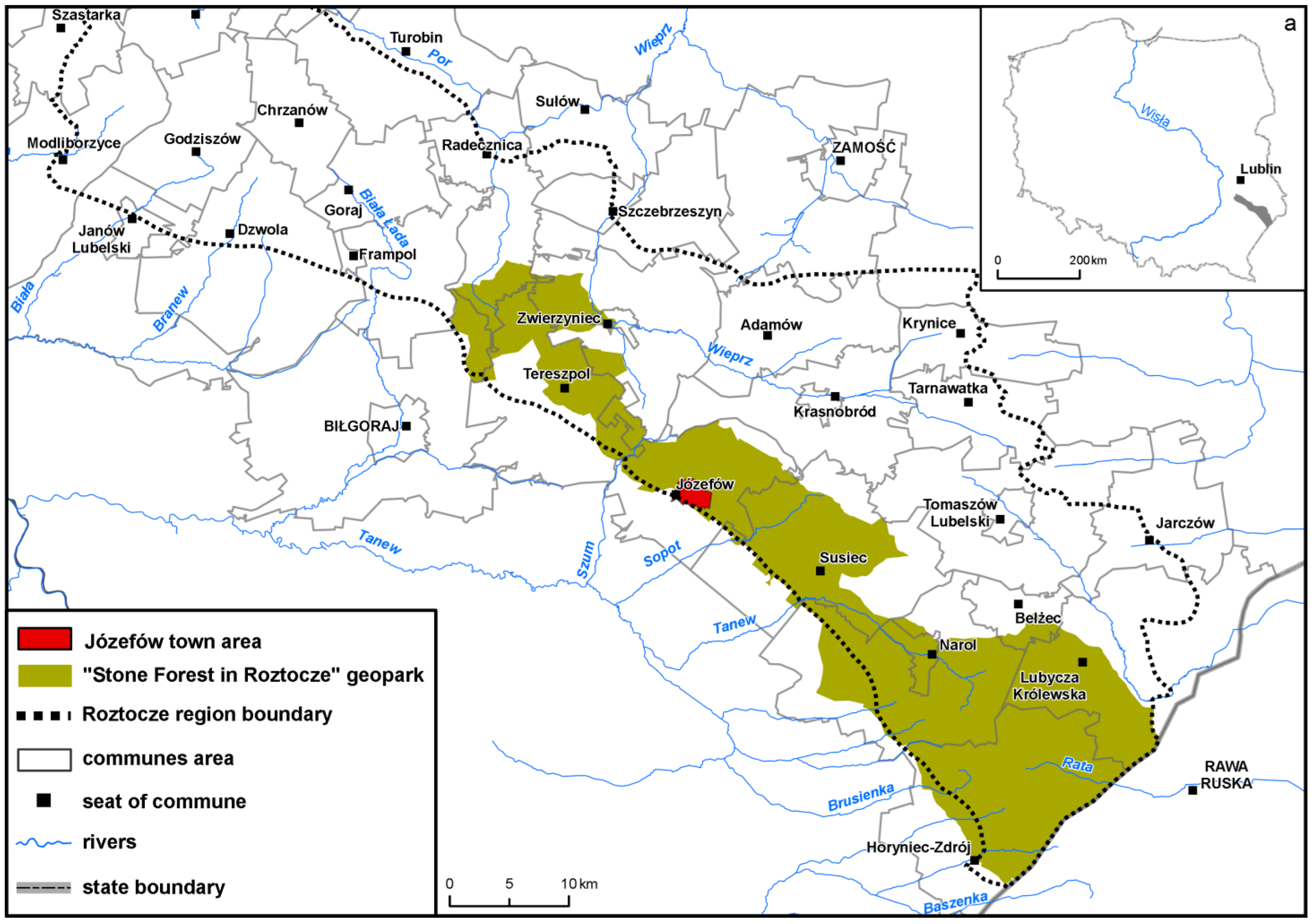

2. Features of the Study Area

2.1. Geological Features and Landforms

2.2. Józefów’s Cultural Heritage Related to Geological Heritage

2.3. Selected Socioeconomic Features

2.4. Józefów’s Geocultural Heritage in the Town’s Current Tourism Product

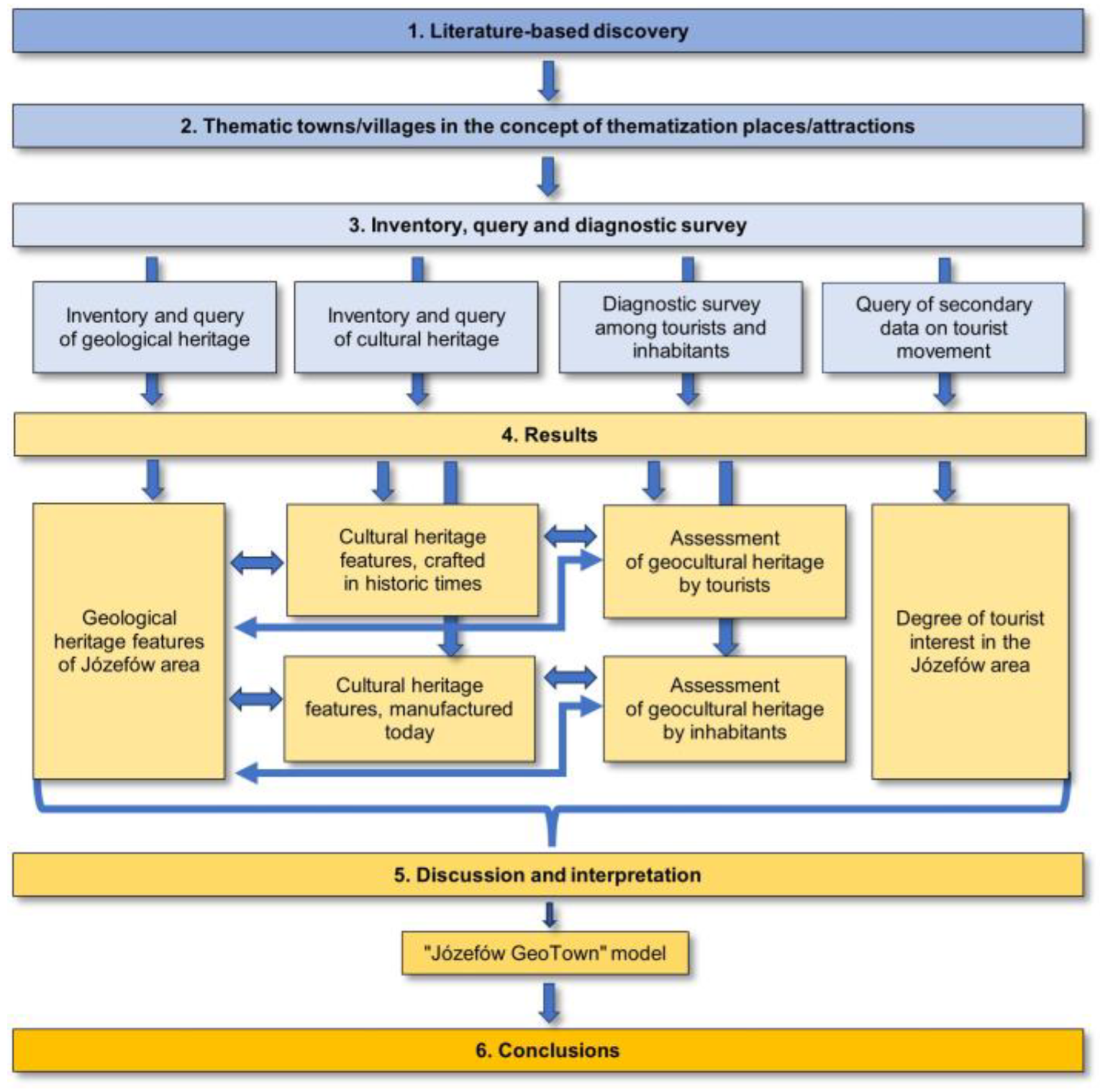

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Features of Józefów’s Geocultural Heritage

4.1.1. Sites Related to Geological Structure and Relief Features

4.1.2. Features of Józefów’s Cultural Heritage Related to Stonework

Miocene Detrital Limestone Objects Crafted in Historic Times

Miocene Detrital Limestone Objects Manufactured from the End of the 20th Century to the Beginning of the 21st Century

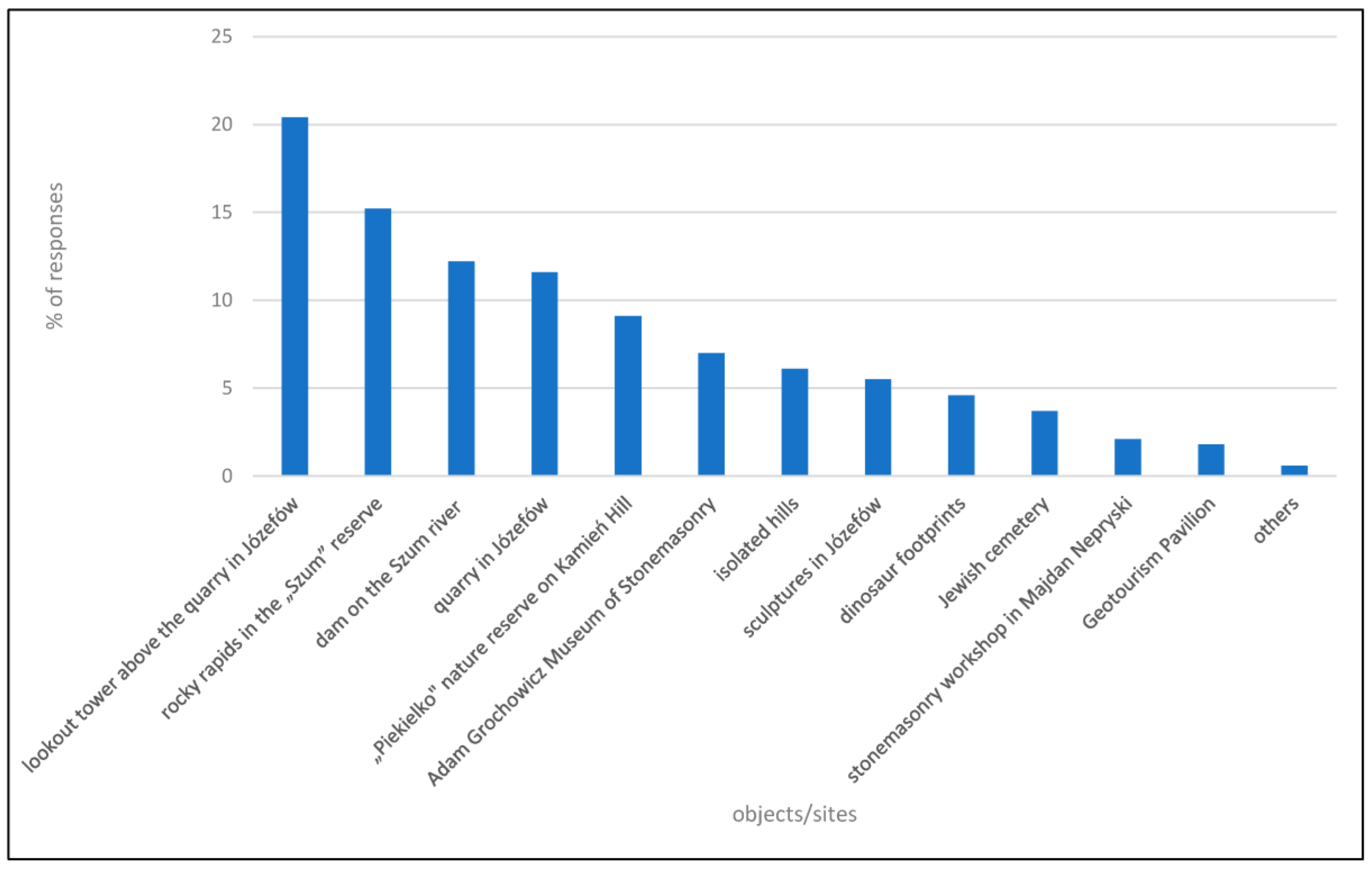

4.2. Tourists’ Interest in the Józefów Area

4.3. Assessment of Józefów’s Geocultural Heritage by Tourists

4.4. Assessment of Józefów’s Geocultural Heritage by the Inhabitants

5. Discussion and Interpretation

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R.K. (Eds.) Geotourism: The Tourism of Geology and Landscape; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, M. Formy turystyki poznawczej. In Turystyka; Kurek, W., Faracik, R., Mika, M., Pawlusiński, W., Pitrus, E., Ptaszycka-Jackowska, D., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2007; pp. 198–231. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A. Geotourism and Interpretation. In Geotourism; Dowling, R., Newsome, D., Eds.; Butterworth Heinemann; Elsevier Science: Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 221–241. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, R.K. Geotourism’s Global Growth. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Monte, M.; Fredi, P.; Pica, A.; Vergari, F. Geosites within Rome city center (Italy): A mixture of cultural and geomorphological heritage. Geogr. Fis. Din. Quat. 2013, 36, 241–257. Available online: http://gfdq.glaciologia.it/036_2_03_2013/ (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Brilha, J. Inventory and quantitative assessment of geosites and geodiversity sites: A review. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, J.T.M.; de Souza Carvalho, I. Geological or Cultural Heritage? The Ex Situ Scientific Collections as a Remnant of Nature and Culture. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijet-Migoń, E.; Migoń, P. Geoheritage and cultural heritage—A review of recurrent and interlinked themes. Geosciences 2022, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollati, I.M.; Caironi, V.; Gallo, A.; Muccignato, E.; Pelfini, M.; Bagnati, T. How to integrate cultural and geological heritage? The case of the Comuniterrae project (Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark, northern Italy). AUC Geogr. 2023, 58, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.I.; Pereira, P.; Brilha, J.; Cunha, P.P. The Iberian Massif Landscape and Fluvial Network in Portugal: A geoheritage inventory based on the scientific value. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2015, 126, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo Abad, C.J. The post-industrial landscapes of Riotinto and Almadén, Spain: Scenic value, heritage and sustainable tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2016, 12, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citiroglu, H.K.; Isik, S.; Pulat, O. Utilizing the geological diversity for sustainable regional development, a case study-Zonguldak (NW Turkey). Geoheritage 2017, 9, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Lista, D.M.; Becerra Becerra, J.E.; Simões de Abreu, M. The historical quarry of Pena (Vila Real, north of Portugal): Associated cultural heritage and reuse as a geotourism resource. Resour. Policy 2022, 75, 102528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.E. Geoheritage, geotourism and the cultural landscape: Enhancing the visitor experience and promoting geoconservation. Geosciences 2018, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fırat, A.F.; Ulusoy, E. Living a theme. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2011, 14, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorens, P. Tematyzacja Przestrzeni Publicznej Miasta; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Gdańskiej: Gdańsk, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Åstrøm, J. Exploring theming dimensions in a tourism context. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottdiener, M. The Theming of America: Dreams, Media Fantasies, and Themed Environments, 1st ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lukas, S.A. The Themed Space: Locating Culture, Nation, and Self; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B. UK theme parks in the 1990s. Tour. Manag. 1991, 12, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.C. Theming Cities, Taming Places: Insights from Singapore. Geogr. Ann. 2000, 82, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, S.; Walton, J. Bavarian Leavenworth and the Symbolic Economy of a Theme Town. Geogr. Rev. 2000, 90, 559–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, P. The Limits of Imagineering: A Case Study of Penang. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, E.; Fırat, A.F. Incorporating the visual into qualitative research: Living a theme as an illustrative example. J. Mark. 2009, 48, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeńca, P. Tematyzacja przestrzeni jako metoda zarządzania rozwojem lokalnym. In Nowoczesne Metody i Narzędzia Zarządzania Rozwojem Lokalnym i Regionalnym; Nowakowska, A., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2015; pp. 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, K. Wioski tematyczne jako przykład innowacyjności w turystyce wiejskiej [summ.: Thematic villages as an example of innovativeness in rural tourism]. Zesz. Nauk. Małopolskiej Wyższej Szkoły Ekon. W Tarnowie 2016, 30, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskiene, I.; Atkociuniene, V. Theming discourse in village development. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference “Economic Science for Rural Development” No 54, Jelgava, Latvia, 12–15 May 2020; pp. 164–171. Available online: https://llufb.llu.lv/conference/economic_science_rural/2020/Latvia_ESRD_54_2020.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Lengkeek, J.; Kloeze, J.W.; Brouwer, R. The Multiple Realities of the Rural Environment. The Significance of Tourist Images for the Countryside. In Images and Realities of Rural Life; de Haan, H., Long, N., Eds.; Wageningen Perspectives on Rural Transformations; Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 324–343. Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/fulltext/359518 (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Kozinets, R.; Sherry, J.; DeBerry-Spence, B.; Duhachek, A.; Nuttavuthisit, K.; Storm, D. Themed flagship brand stores in the new millennium: Theory, practice, prospects. J. Retail. 2002, 78, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, T.W. Theming, tourism, and fantasy city. In A Companion to Tourism; Lew, A.A., Hall, M.C., Williams, A.M., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viken, A.; Granås, B. Dimensions of tourism destinations. In Tourism Destination Development: Turns and Tactics; Viken, A., Granås, B., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Surrey, UK, 2014; pp. 1–17. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/1635392/tourism-destination-development-turns-and-tactics-pdf (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Mossberg, L.M. Extraordinary experiences through storytelling. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2008, 8, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fırat, A.F.; Ulusoy, E. Why thematization? In NA—Advances in Consumer Research; Mcgill, A.L., Shavitt, S., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 2009; pp. 777–778. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, P. Rural landscapes: Case study of Village Plans in Central Portugal (“Network of Schist Villages”). In European Farming and Society in Search of a New Social Contract: Learning to Manage Change; UTAD/IFSA: Vila Real, Portugal, 2004; pp. 233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Scheurer, R. Theme park tourist destinations: Creating an experience setting in traditional tourist destinations with staging strategies of theme parks. In The Tourism and Leisure Industry: Shaping the Future; Weiermair, K., Mathies, C., Eds.; Research Institute for Leisure and Tourism, University of Berne: Berne, Switzerland, 2004; pp. 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Waldrep, S. The Dissolution of Place: Architecture, Identity, and the Body, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, J.H.; Pine, B.J. Differentiating hospitality operations via experiences: Why selling services is not enough. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2002, 43, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, S.A. The Immersive Worlds Handbook: Designing Theme Parks and Consumer Spaces, 1st ed.; Taylor and Francis: Burlington, MA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780240820989/immersive-worlds-handbook-scott-lukas (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Dale, C.; Robinson, N. The theming of tourism education: A three-domain approach. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 13, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, J.; Stasiak, A.; Włodarczyk, B. Produkt Turystyczny. Pomysł-Organizacja-Zarządzanie; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. Tourism 2020. Vision Global Forecasts and Profiles of Market Segments; United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Farsani, N.T.; Coelho, C.; Costa, C. Rural Geotourism: A New Tourism Product. Acta Geotur. 2013, 4, 1–10. Available online: https://geotur.tuke.sk/pdf/2013/n02/01_Torabi_v4_n2.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Hose, T.A. 3G’s for Modern Geotourism. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marková, B.; Boruta, T. The Potential of Cultural Events in the Peripheral Rural Jesenicko Region. AUC Geogr. 2012, 47, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blichfeldt, B.S.; Halkier, H. Mussels, Tourism and Community Development: A Case Study of Place Branding Through Food Festivals in Rural North Jutland, Denmark. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1587–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E. A geological walk around the City of London—Royal exchange to Aldgate. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 1982, 93, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idziak, W. Wymyślić Wieś od Nowa. Wioski Tematyczne; Wyd. Alta Press: Koszalin, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kłoczko-Gajewska, A. General characteristics of thematic villages in Poland. Visegr. J. Bioeconomy Sustain. Dev. 2013, 2, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigbu, U.E. Village renewal as an instrument of rural development: Evidence from Weyarn, Germany. Community Dev. 2012, 43, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka-Ożga, L.; Ożga, W. Nowe spojrzenie na edukację przyrodniczą na przykładzie wybranych wiosek tematycznych w Polsce. Stud. Mater. CEPL Rogowie 2014, 16, 193–199. Available online: https://cepl.sggw.edu.pl/wp-content/uploads/sites/75/2021/08/SIM_38_Chojnacka_Ozga.pdf?x68467 (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Kowalska, N. Wioski tematyczne jako przykład innowacji w turystyce na terenie pogórniczym. Tur. Kult. 2019, 4, 7–19. Available online: http://turystykakulturowa.org/ojs/index.php/tk/article/view/1058 (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Podolska, A. Rozwój obszarów wiejskich w oparciu o ideę tworzenia wiosek tematycznych. [summ. Development of rural areas based on the idea of creating thematic villages]. Stud. Obsz. Wiej. 2018, 49, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koral, J.; Rościszewska, E. Bałtów—Gmina, Którą Ożywiły Dinozaury; Fundacja Inicjatyw Społeczno-Ekonomicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 2007; Available online: http://www.ekonomiaspoleczna.pl/files/ekonomiaspoleczna.pl/public/Atlas_dobrych_praktyk/1Atlas_Dobrych_Praktyk_Baltow.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Czapiewska, G. Wpływ środków Unii Europejskiej na pobudzenie inicjatyw społeczności wiejskich obszarów peryferyjnych województwa zachodniopomorskiego. Stud. Obsz. Wiej. 2011, XXVI, 233–248. Available online: http://rcin.org.pl/igipz/Content/19348/WA51_38451_r2011-t26_SOW.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Idziak, M. Wioski Tematyczne w Polsce w Latach 1997–2013. 2013. Available online: http://ekonomiaspoleczna.pisop.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Za%C5%82%C4%85cznik-nr-7-%E2%80%93-Dobre-praktyki-%E2%80%9EWioski-tematyczne-w-Polsce-w-latach-od-1997-do-2013%E2%80%9D-M.-Idziak.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Cropp, D. Small is beautiful—The concept of the geovillage as a community-led asset. In Proceedings of the 14th European Geoparks Conference, Azores, Portugal, 7–9 September 2017; p. 147. Available online: https://globalgeoparksnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Abstracts.Book_.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Górska-Zabielska, M. A New Geosite as a Contribution to the Sustainable Development of Urban Geotourism in a Tourist Peripheral Region—Central Poland. Resources 2023, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, M.H.; Tomaz, C.; Sá, A.A. The Arouca Geopark (Portugal) as an Educational Resource: A Case Study. Episodes 2012, 35, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, J.; de Carvalho, C.N.; Ramos, M.; Ramos, R.; Vinagre, A.; Vinagre, H. Geoproducts—Innovative development strategies in UNESCO Geoparks: Concept, implementation methodology, and case studies from Naturtejo Global Geopark, Portugal. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2021, 9, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F. Ancient Stone Village Built of Volcanic Rock. Available online: https://www.shine.cn/feature/travel/2107021456/ (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Breda, Z.; Costa, R.; Costa, C. Do Clusters and Networks Make Small Places Beautiful? The Case of Caramulo (Portugal). In Tourism Local Systems and Networking; Lazzeretti, L., Petrillo, C.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Geraldes, J.; Ferreira, R. Geotourism “Tectonics” and Geo-bakery. In Proceedings of the VIII European Geoparks Conference, Idanha-a-Nova, Portugal, 4–6 September 2009; pp. 100–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, J.; Neto de Carvalho, C. Geoproducts in Geopark Naturtejo. In Proceedings of the VIII European Geoparks Conference, Idanha-a-Nova, Portugal, 4–6 September 2009; pp. 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C.N.; Rodrigues, J. Building a Geopark for Fostering Socio-economic Development and to Burst Culture Pride: The Naturtejo European Geopark (Portugal). In Una Visión Multidisciplinar del Patrimonio Geológico y Minero; Florido, P., Rábano, I., Eds.; Cuadernos del Museo Geominero Nº 12, Instituto Geológico y Minero de Espańa: Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 467–479. Available online: https://books.google.pl/books?id=eZlyqyIZbaAC&pg=PA33&hl=pl&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=2#v=onepage&q=Naturtejo&f=false (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Pagès, J.-S. The GeoPark of Haute-Provence, France—Geology and Palaeontology Protected for Sustainable Development. In PaleoParks—The Protection and Conservation of Fossil Sites Worldwide; Lipps, J.H., Granier, B.R.C., Eds.; Notebooks on Geology: Brest, France, 2009; Book 3, Chapter 3; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Maćkowiak, M.; Jęczmyk, A. Strategia hands-on activity w turystyce wiejskiej i jej wykorzystanie w tworzeniu edukacyjnych produktów turystycznych. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Wrocławiu 2013, 304, 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezińska-Wójcik, T. Strategia hands-on activity w kreowaniu geoproduktów w kontekście edukacji, interpretacji i promocji geodziedzictwa na Roztoczu (środkowowschodnia Polska). Ekon. Probl. Tur. 2015, 29, 169–193. Available online: https://bazhum.muzhp.pl/media/files/Ekonomiczne_Problemy_Turystyki/Ekonomiczne_Problemy_Turystyki-r2015-t-n1_(29)/Ekonomiczne_Problemy_Turystyki-r2015-t-n1_(29)-s169-193/Ekonomiczne_Problemy_Turystyki-r2015-t-n1_(29)-s169-193.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Fassoulas, C.; Zouros, N. Evaluation the Influence of Greek Geoparks to the Local Communities. In Proceedings of the 12th International Congress Planet Earth, Patras, Greece, 19–22 May 2010; pp. 896–906. Available online: https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/geosociety/article/view/11255/11301 (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/iggp/geoparks (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Ruban, D.A.; Mikhailenko, A.V.; Yashalova, N.N.; Scherbina, A.V. Global geoparks: Opportunity for developing or “toy” for developed? Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2023, 11, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. History of Geoparks; Special Publications; Geological Society: London, UK, 2008; Volume 300, pp. 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, M.H.; Brilha, J. UNESCO Global Geoparks: A strategy towards global understanding and sustainability. Episodes 2017, 40, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrowicz, Z. Perspektywy rozwoju geoochrony w krajach Wspólnoty Europejskiej. Chrońmy Przyr. Ojczystą 2004, 60, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall, P.; Weighell, T.; Badman, T. Geological World Heritage: A Global Framework. A Contribution to the Global Theme Study or World Heritage Natural Sites; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2005; Available online: https://www.iucn.org/content/geological-world-heritage-a-global-framework (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Alexandrowicz, Z. Geoochrona w ujęciu narodowym, europejskim i światowym (ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem Polski). Biul. Państwowego Inst. Geol. 2007, 425, 19–26. Available online: https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-article-AGHM-0008-0060?q=bwmeta1.element.baztech-volume-0867-6143-biuletyn_panstwowego_instytutu_geologicznego-2007-nr_425;2&qt=CHILDREN-STATELESS (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Patzak, M.; Eder, W. “UNESCO GEOPARK” A new Programme—A new UNESCO label. Geol. Balc. 1998, 28, 33–35. Available online: https://www.geologica-balcanica.eu/journal/28/3-4/pp.-33-35 (accessed on 19 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Alexandrowicz, Z.; Alexandrowicz, S.W. Geoparks—The most valuable landscape parks in southern Poland. Pol. Geol. Inst. Spec. Pap. 2004, 13, 49–56. Available online: https://www.pgi.gov.pl/oferta-inst/wydawnictwa/serie-wydawnicze/pgi-special-papers/6066-special-papers-2004-tom-13.html (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Krąpiec, M.; Jankowski, L.; Margielewski, W.; Urban, J.; Krąpiec, P. The Stone Forest (Kamienny Las) Geopark in Roztocze and its geoturistic values. Przegląd Geol. 2012, 60, 468–479. Available online: https://www.pgi.gov.pl/docman-tree/publikacje-2/przeglad-geologiczny/2012-1/wrzesien-2/1120-geopark-kamienny-las/file.html (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Kurkowski, S. Szczegółowa Mapa Geologiczna Polski, Arkusz JÓZEFÓW (927), 1:50000; Wyd. Państwowego Instytutu Geologicznego: Warszawa, Poland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezińska-Wójcik, T.; Skowronek, E.; Kondraciuk, P. Możliwości wykorzystania dziedzictwa ośrodków kamieniarskich Roztocza w turystyce. Tur. I Rekreac.—Stud. I Pr. Uwarunk. I Plany Rozw. Tur. 2015, 15, 91–108. Available online: http://turystyka.amu.edu.pl/tomy/tir15.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Musiał, T. Miocen Roztocza (Polska południowo-wschodnia). Biul. Geol. 1987, 31, 5–75. [Google Scholar]

- Jaroszewski, W. Sedymentacyjne przejawy mioceńskiej ruchliwości tektonicznej na Roztoczu Środkowym. Przegląd Geol. 1977, 25, 418–427. Available online: https://geojournals.pgi.gov.pl/pg/article/view/21850/15533 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Wysocka, A.; Jasionowski, M.; Peryt, T. Miocen Roztocza. Biul. Państwowego Inst. Geol. 2007, 422, 79–96. Available online: https://geojournals.pgi.gov.pl/bp/article/view/32269 (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Solon, J.; Borzyszkowski, J.; Bidłasik, M.; Richling, A.; Badora, K.; Balon, J.; Brzezińska-Wójcik, T.; Chabudziński, Ł.; Dobrowolski, R.; Grzegorczyk, I.; et al. Physico-geographical mesoregions of Poland—Verification and adjustment of boundaries on the basis of contemporary spatial data. Geogr. Pol. 2018, 91, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, L.; Margielewski, W. Pozycja tektoniczna Roztocza w świetle historii rozwoju zapadliska przedkarpackiego. Biul. Państwowego Inst. Geol. 2015, 462, 7–28. Available online: https://geojournals.pgi.gov.pl/bp/article/view/28736 (accessed on 28 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Cieśliński, S.; Kubica, B.; Rzechowski, J. Mapa Geologiczna Polski. 1:200,000, ark. Tomaszów Lubelski, Dołhobyczów. B—Mapa bez Utworów Czwartorzędowych; Wydawnictwo Kartograficzne Polskiej Agencji Ekologicznej, S.A.: Warszawa, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Harasimiuk, M. Rzeźba Strukturalna Wyżyny Lubelskiej i Roztocza; Wydz. BiNoZ UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezińska-Wójcik, T. Morfotektonika w Annopolsko-Lwowskim Segmencie pasa Wyżynnego w Świetle Analizy Cyfrowego Modelu Wysokościowego oraz Wskaźników Morfometrycznych; Uniwersytet Marii Curie Skłodowskiej: Lublin, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maruszczak, H.; Wilgat, T. Rzeźba strefy krawędziowej Roztocza Środkowego. Ann. UMCS B 1956, X, 107–170. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecka, B.; Janiec, B. Przełomy Rzeczne Roztocza Jako Modelowe Obiekty w Edukacji Ekologicznej; Wydawnictwo UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kawałko, D. Józefowski ośrodek kamieniarski. Materiały Ogólnopolskiej Sesji Popularno-Naukowej w Zamościu: Zamość, Poland, 22–24.IX.1995 r.; pp. 46–61. Available online: http://biblioteka.teatrnn.pl/dlibra/Content/11058/Przyczynki_do_etnografii_Zamojszczyzny.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Witusik, A.A. O Zamoyskich, Zamościu i Akademii Zamojskiej; Wydawnictwo Lubelskie: Lublin, Poland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Rocznik Statystyczny. Województwo Lubelskie. Podregiony. Powiaty. Gminy; Urząd Statystyczny w Lublinie: Lublin, Poland, 2019.

- Available online: https://www.ejozefow.pl/turystyka/baza-noclegowa.html (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Available online: https://www.bilgorajski.pl/9-uncategorised/138-baza-gastronomiczna (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Available online: http://jkr.org.pl/ (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Available online: https://www.lgdnaszeroztocze.pl/trasy-nordic-walking-gmina-jozefow/ (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Brzezińska-Wójcik, T.; Grabowski, T.; Moskal, A.; Pawłowski, A.; Wiechowska, I. Część Opisowa do Mapy “Szlak Geoturystyczny Roztocza Środkowego”; Informator—Mapa Turystyczna 1:50,000; Kartpol: Lublin, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: http://jkr.org.pl/index.php?id=galeria (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Kula, S. Percepcja i wykorzystanie walorów turystycznych Roztocza przez osoby odwiedzające region. In Wpływ Sektora B+R na Wzrost Polskiej Konkurencyjności Polskiej Gospodarki Poprzez Rozwój Innowacji, t. 1; Jegorow, D., Niedużak, A., Eds.; Wydawnictwo CIVIS: Chełm, Poland, 2012; pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezińska-Wójcik, T. “Roztocze—Witalność z natury” brand as an indicator of abiotic assets in marketing slogans and tourism products. Econ. Probl. Tour. 2018, 4, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisera, A. Paleoecology and lithogenesis of the Middle Miocen (Badenian) algal-vermetid reefs from the Roztocze Hills, south-eastern Poland. Acta Geol. Pol. 1985, 35, 89–155. [Google Scholar]

- Wysocka, A.; Roniewicz, P. Representative Geosites of the Roztocze Hills. Pol. Geol. Inst. Spec. Pap. 2004, 13, 137–144. Available online: https://www.pgi.gov.pl/docman-tree/publikacje-2/special-papers/13/2414-13-polish-geological-institute-special-papers-13-18-wysocka-roniewicz-representative-geosites-of-the-roztocze-hills/file.html (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Brzezińska-Wójcik, T.; Chabudziński, Ł. 002177: Kamieniołom w Józefowie—Krasowe Formy Kopalne. 2010. Available online: http://geostanowiska.pgi.gov.pl/gsapp_v2/ObjectDetails.aspx?id=2177 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Jankowski, L. 001209: Kamieniołom w Józefowie—Mioceńskie Wapienie. 2005. Available online: http://geostanowiska.pgi.gov.pl/gsapp_v2/ObjectDetails.aspx?id=1209 (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Zgłobicki, W.; Kukiełka, S.; Baran-Zgłobicka, B. Regional Geotourist Resources—Assessment and Management (A Case Study in SE Poland). Resources 2020, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezińska-Wójcik, T.; Zieliński, P. Wydma w Józefowie. 2010. Available online: http://geostanowiska.pgi.gov.pl/gsapp_v2/ObjectDetails.aspx?id=2186 (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Brzezińska-Wójcik, T.; Chabudziński, Ł. 002147: Źródlisko Niepryszki w Józefowie. 2010. Available online: http://geostanowiska.pgi.gov.pl/gsapp_v2/ObjectDetails.aspx?id=2147 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Available online: https://www.ejozefow.pl/turystyka/warto-zobaczy%C4%87.html (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Frey, M.L.; Schäefer, K.; Büchel, G.; Patzak, M. Geoparks—A regional, European and global policy. In Geotourism, Sustainability, Impacts and Management; Newsome, D., Dowling, R., Eds.; Butterworth Heinemann, Elsevier Science: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 96–117. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Site Name | Features/Location of the Object | Number of Sites and/or Elements | Location of Sites in Figure 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tombstones | By the church | 4 | 021 |

| 2 | Chapel | Virgin Mary with child | 1 | 014 |

| 3 | Roadside cross | By the street | 1 | 014 |

| No. | Site Name | Features/Location of the Object | Number of Sites and/or Elements | Location of Sites in Figure 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Facades | Private buildings | 8 | 013, 016, 018, 023, 024, 026, 029, 031 |

| 2 | Fences (including gates) | Private properties | 12 | 004, 012 (2 fences), 013, 014, 015, 016, 017, 023, 024, 027 |

| 3 | Building buttresses | Private buildings | 1 | 017 |

| 4 | Construction elements of the shelter over the well | Town square | 1 | 011 |

| 5 | Gazebo | By a private property | 1 | 014 |

| No. | Site Name | Features/Location of the Object | Number of Sites and/or Elements | Location of Sites in Figure 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sculptures | Pelican, Aquarius, and Neptune—by the recreational pond | 3 | 001 |

| Fish—in the town square | 2 | 011 | ||

| Bull, bear, man, woman, column, limestone block, grieving man, warrior—in the town square | 8 | 011 | ||

| Jesus—in the town square | 1 | 030 | ||

| Various—by a private property | 3 | 013 | ||

| St. Stanislaus | 1 | 015 | ||

| Queen Jadwiga | 1 | 019 | ||

| Jesus with the lambs | 1 | 020 | ||

| Mary (mother of Jesus) praying, memorial of the wooden altar in the church, John Paul II, cross, St. Dominic | 5 | 021 | ||

| Inverted mask | 1 | 025 | ||

| Elephants—by the school complex | 2 | 028 | ||

| 2 | Flowerpots | In the town square | 4 | 011 |

| By a private building | 2 | 017 | ||

| 3 | Monuments | Memorial Monument—in the town square | 1 | 008 |

| By the church | 1 | 022 | ||

| Monument to the Battle of Józefów—by the quarry | 1 | 007 | ||

| 4 | Small wall surrounding the fountain | In the town square | 1 | 008 |

| 5 | Sundial | 1 | 010 | |

| 6 | Copy of the pillory from the 18th century | 1 | 009 |

| No. | Site Name | Features/Location of the Object | Number of Sites and/or Elements | Location of Sites in Figure 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Benches and tables | By the recreational pond | 2 sets | 001 |

| 2 | Litter bins | 5 sets | ||

| 3 | Sheds/gazebos | 4 | 002 | |

| 4 | Bar building | 1 | 003 | |

| 5 | Toilet building | 1 | ||

| 6 | Benches | By the Geotourism Pavilion | 2 | 011 |

| 7 | Bus stop building | In the town square | 2 | 032 |

| 8 | Lookout tower | At the quarry | 1 | 006 |

| 9 | Geotourism Pavilion with lapidarium | In the town square | 1 | 011 |

| Years | Data Sources | Total Number of Tourists | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Statistical Office—Overnight Stays | TIC (May–October), Including the Geotourism Pavilion, Tower and Quarry, Cycle Rallies | PTSS in Zamość—Walking Rallies/Bus Tours | Office of the Marshal of the Lubelskie Voivodeship—Cycling | ||

| 2017 | 1628 | 3380 | 754 | No data | 5762 |

| 2018 | 1068 | 3535 | 50 | No data | 4653 |

| 2019 | 1218 | 3634 | 326 | No data | 5178 |

| 2020 | 774 | 3274 | 302 | 25,084 | 29,434 |

| 2021 | 961 | 3317 | 48 | 31,327 | 35,653 |

| 2022 | 421 | 3280 | 310 | 30,797 | 34,808 |

| Voivodeships | Years | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |||||||

| (May–October) | (May–November) | (July–October) | (May–October) | |||||||||

| Tourists | ||||||||||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Mazowieckie | 665 | 19.67 | 525 | 14.93 | 452 | 12.43 | 653 | 19.94 | 502 | 15.13 | 368 | 11.21 |

| Lubelskie | 570 | 16.86 | 819 | 23.16 | 982 | 27.02 | 565 | 17.22 | 705 | 21.25 | 715 | 21.79 |

| Małopolskie | 491 | 14.52 | 488 | 13.80 | 387 | 10.64 | 388 | 11.85 | 372 | 11.21 | 477 | 14.54 |

| Śląskie | 401 | 11.86 | 394 | 11.14 | 564 | 15.52 | 721 | 22.02 | 648 | 19.53 | 654 | 19.93 |

| Łódzkie | 204 | 6.03 | 257 | 7.27 | 165 | 4.54 | 207 | 6.32 | 212 | 6.39 | 221 | 6.73 |

| Dolnośląskie | 193 | 5.71 | 242 | 6.84 | 270 | 7.42 | 168 | 5.13 | 214 | 6.45 | 204 | 6.21 |

| Wielkopolskie | 193 | 5.71 | 222 | 6.28 | 176 | 4.84 | 112 | 3.42 | 103 | 3.10 | 120 | 3.65 |

| Podkarpackie | 187 | 5.53 | 274 | 7.75 | 298 | 8.20 | 295 | 9.01 | 210 | 6.33 | 212 | 6.46 |

| Pomorskie | 170 | 5.02 | 66 | 1.86 | 68 | 1.87 | 66 | 2.01 | 132 | 3.97 | 98 | 2.98 |

| Other voivodeships | 232 | 7.02 | 196 | 5.63 | 200 | 5.61 | 99 | 3.02 | 219 | 6.60 | 211 | 6.43 |

| No data | 0 | 0.00 | 52 | 1.46 | 72 | 1.98 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 3306 | 97.74 | 3483 | 100.00 | 3562 | 99.94 | 3274 | 99.91 | 3317 | 99.95 | 3280 | 99.95 |

| Features | Total Points Scored | Average Score (1–5 Points) | Average Score from Averages (1–5 Points) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural resources | 97 | 4.9 | 3.8 |

| Stonemasonry | 90 | 4.5 | |

| Active recreation opportunities | 90 | 4.5 | |

| Large number of bicycle routes | 81 | 4.1 | |

| History | 72 | 3.6 | |

| Cultural heritage | 68 | 3.4 | |

| Long distance from large urban centres | 63 | 3.2 | |

| Good gastronomy facilities | 61 | 3.1 | |

| Good accommodation | 59 | 3.0 |

| Features | Total Points Scored | Average Score (1–5 Points) | Average Score from Averages (1–5 Points) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stonemasonry workshop in Majdan Nepryski | 29 | 4.8 | 4.0 |

| Lookout tower over the “Babia Dolina” quarry | 67 | 4.8 | |

| Józefów quarry | 69 | 4.6 | |

| Sculptures made from local limestone | 27 | 4.5 | |

| Spring of the Niepryszka River | 40 | 4.4 | |

| Rocky rapids in the bed of the Niepryszka River | 20 | 4.0 | |

| Recreational pond with a beach | 40 | 4.0 | |

| Matzevot on the Jewish cemetery | 34 | 3.8 | |

| Geotourism Pavilion | 18 | 3.6 | |

| Józefów fishpond | 22 | 3.1 | |

| Parish cemetery with tombstones of local limestone | 22 | 3.1 | |

| Adam Grochowicz Museum of Stonemasonry | 13 | 2.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brzezińska-Wójcik, T. Geocultural Heritage as a Basis for Themed GeoTown—The “Józefów StoneTown” Model in the Roztocze Region (SE Poland). Sustainability 2024, 16, 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031188

Brzezińska-Wójcik T. Geocultural Heritage as a Basis for Themed GeoTown—The “Józefów StoneTown” Model in the Roztocze Region (SE Poland). Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031188

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrzezińska-Wójcik, Teresa. 2024. "Geocultural Heritage as a Basis for Themed GeoTown—The “Józefów StoneTown” Model in the Roztocze Region (SE Poland)" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031188

APA StyleBrzezińska-Wójcik, T. (2024). Geocultural Heritage as a Basis for Themed GeoTown—The “Józefów StoneTown” Model in the Roztocze Region (SE Poland). Sustainability, 16(3), 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031188